#Accipitrimorph

Text

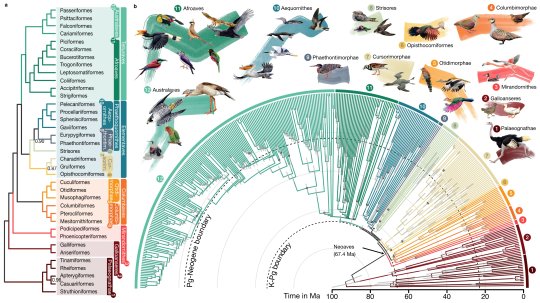

With recent advances in genetic sequencing and analysis, we now have a pretty good idea of how most modern vertebrate animals are related to each other. One of the biggest remaining mysteries in vertebrate evolution (and a major theme of my own research), however, is the relationships among the major groups of living birds.

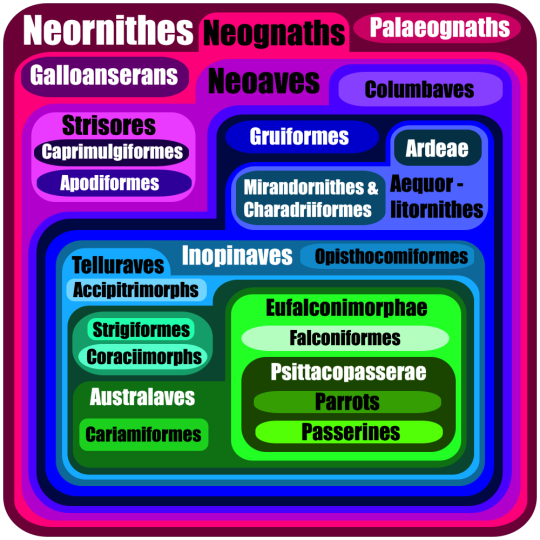

There are some things that we all agree on about the bird family tree (which in some cases were already recognized before the rise of genetic studies), a big one being that modern birds can be divided into two major branches: Palaeognathae (ostriches, emus, and their close relatives) and Neognathae (all other living birds). Neognathae is in turn divided into Galloanserae (chickens, ducks, and their close relatives) and Neoaves (all remaining birds, which constitute 95% of living bird diversity).

Despite birds being one of the most intensely studied animal groups, however, essentially none of the large-scale genetic analyses that have been done on them so far have agreed with each other regarding how the major groups within Neoaves are related.

A new study by Stiller et al. (2024) might represent a big step forward in solving this mystery. Their results suggest that Neoaves can be divided into four major groups.

Mirandornithes: Flamingos and grebes. Stiller et al. found that all other members of Neoaves are probably more closely related to each other than to this group.

Columbaves: Consisting of two major subgroups, Otidimorphae (cuckoos, bustards, and turacos) and Columbimorphae (pigeons, sandgrouse, and mesites). Notably, Columbimorphae has been found by some earlier studies to be more closely related to Mirandornithes, but a second paper that was published on the same day by some of the same authors as Stiller et al. (2024) reported evidence that this previous result was probably caused by misleading similarities between the genetic sequences of Columbimorphae and Mirandornithes.

Elementaves: Consisting of Gruiformes (cranes and their close relatives), Charadriiformes (shorebirds), Strisores (hummingbirds, swifts, nightjars, and their close relatives), Phaethoquornithes (many waterbirds, including penguins, albatrosses, and herons), and the engimatic hoatzin. The exact relationships among these groups are still somewhat unclear; for example, Stiller et al. found the hoatzin to be most closely related to gruiforms and shorebirds (as had been suggested by an earlier study), but support for this result was not high. The hoatzin remains the single most difficult bird species to place in the bird family tree. The name Elementaves was newly coined by Stiller et al., referring to the fact that this group includes species specialized for life in the water, on the ground, and in the air (corresponding to the classical elements of water, earth, and air), as well as birds named after the sun ("fire"), such as the tropicbird genus Phaethon (Ancient Greek for "sun") and the sunbittern. This means that there is now a scientific basis for parodying Avatar: The Last Airbender using birds.

Telluraves: A big group consisting primarily of tree-dwelling birds, including songbirds, parrots, woodpeckers, kingfishers, and the various groups of birds of prey. An interesting result found by Stiller et al. is that owls are likely closely related to accipitrimorphs (hawks, eagles, vultures, etc.), which not all previous genetic studies had supported.

Stiller et al. (2024) provide further evidence for some bird relationships found by earlier analyses, but their results still doesn't exactly match those of any single previous study, so what makes this different from all those attempts that came before it? One is the amount of data. The genetic dataset analyzed by Stiller et al. was many times larger (both in terms of sequence length and the types of genes examined) than any study of this sort that had previously been done on birds. They also included over 360 bird species, which is more than what most previous studies had. Furthermore, they ran numerous tests to determine how the amount of data, number of species, and types of genes analyzed affected their findings, and in doing so were able to show that most of their results were relatively robust, or at least better supported than alternative hypotheses.

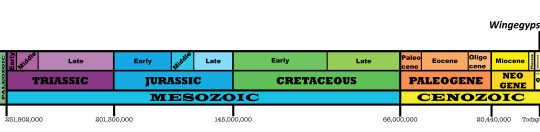

Another point of contention regarding the evolution of Neoaves is when the group originated. Were there already many neoavian lineages around during the Late Cretaceous, or did they mostly diversify following the mass extinction event that ended it? In the 2000s and early 2010s, studies trying to estimate the ages of bird groups based on rates of genetic evolution tended to find an older origin for Neoaves, but the majority of newer studies favor a younger origin, with most or all modern neoavian groups appearing after the Cretaceous (though one paper from earlier this year by a different team of authors advocated for older ages). Informed by recent studies on fossil birds, the results of Stiller et al. add further support for a more recent, mainly post-Cretaceous diversification of Neoaves (which I happen to think is more plausible than deep Cretaceous origins).

This almost certainly won't be the last word on these controversies by any means. However, at the moment I'm willing to tentatively consider Stiller et al. (2024) the closest we've gotten to approximating the true family tree of birds, and that is not a declaration I'd make lightly.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Neophron percnopterus

By Koshy Koshy, CC BY 2.0

Etymology: A Childish Trickster

First Described By: Savigny, 1809

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Inopinaves, Telluraves, Afroaves, Accipitrimorphae, Accipitriformes, Accipitridae, Gypaetinae

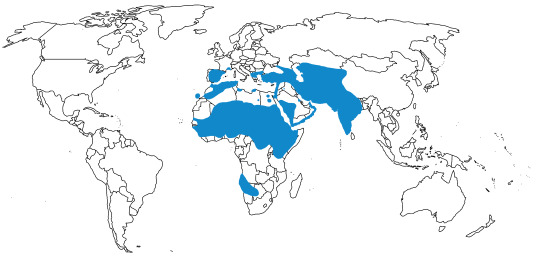

Status: Extant, Endangered

Time and Place: Since 12,000 years ago, in the Holocene of the Quaternary

Egyptian Vultures are known from locations across India, Western Asia, Africa, and Southern Europe

Physical Description: The Egyptian Vulture is a small vulture, only about 54 to 70 centimeters long with a wingspan of a little more than twice that size. It is also very distinctive in color, and extremely fluffy (which makes sense, given it is probably closely related to the Bearded Vulture). It has a very long and narrow head, which is bare and yellow over the eyes and beak; the tip of the beak is sharply hooked and black. The back of the head and neck is very fluffy and white. The rest of the body is also very puffed, mostly white but with black edges and tips to the wing feathers and tail feathers. It has white fluffy legs, with only some of the feet bear; the feet are pale in color. The females are usually much heavier than the males. The juveniles are significantly darker than the adults in color.

By Carlos Delgado, CC BY-SA 3.0

Diet: Egyptian Vultures primarily feed on large dead animals such as carrion of birds, livestock, wild mammals, and even dogs. Usually it will prefer scraps from large carcasses. Sometimes it will also eat eggs!

By Вых Пыхманн, CC By-SA 3.0

Behavior: These vultures are pragmatic opportunists, eating a wide variety of carrion that are often rejected by other vulture. It even competes often with crows and other corvids - more pragmatic, intelligent birds! These vultures spend a lot of the day soaring overhead, searching for food from up to one kilometer away; they also will perch and search for food on trees and cliffs. They tend to congregate in large numbers where there is good sources of food - even though this bird is rare. They will pull off chunks of carcass and often will throw stones at eggs to open them up - a documented use of tools! They also will use twigs to roll up and gather strands of wool for nest-lining. They aren’t very loud birds, making small whistles, grunts, groans, and hisses when needed. Somewhat social birds, they are usually found in pairs or in large groups around carcasses, though often they spend time alone.

By Jiel, CC BY-SA 4.0

Egyptian Vultures breed in the spring, with pairs courting by soaring high together and then swooping and spiraling down. They are monogamous for at least one breeding season, and may stay with the same mate for many years or even their whole lives. They tend to come back to the same nest sites year after year. They make nests out of twigs and wool, placed on cliff ledges and on large tree forks. Neighboring birds may form polyamorous groups with a mated pair, allowing for the two pairs of adults to aid each other in caring for the young. Usually the birds prepare for copulation by giving each other food, and preening each other to get in the “mood”. They lay around two eggs usually, which are incubated for around one and a half months. All adults will incubate the chicks, which are very brown and puffy. They stay in the nest for up to three months, cared for by the parents for most of that time. They reach sexual maturity between 4 and 6 years of age, and can live for nearly four decades, though most tend to die by the fifth year of life in the wild.

By PJeganathan, CC BY-SA 4.0

The vultures tend to soar on thermal wind, using the heat to raise themselves higher in the air; on the land they’re much less graceful, waddling around awkwardly. They are very calculating animals, waiting for predators to leave a carcass before approaching. They’ll even feed on poop to get carotenoids - pigments - from large herbivorous mammals. They tend to migrate only in the northern part of their range - in Africa and India, they stay mainly in the same location year-round. They glide extensively while flying, wasting as little energy while migrating as possible.

By Dr. Raju Kasambe, CC BY-SA 4.0

Ecosystem: Egyptian Vultures prefer open areas, preferably ones with dry and arid habitat. They especially prefer locations near cold and wet climates, such as scrub habitats. They also frequent deserts, steppes, pastures, and some fields, though they try to stay near rocky places when nesting. They also can be found in mountainous regions at lower or mid-level altitudes. They are hunted upon by golden eagles, eagle owls, and red foxes as young; they also are very vulnerable to other mammalian predators (like wolves) as adults and to human interference. In fact, human activity takes a toll on population size.

By Tomasz Baranowski, CC BY 2.0

Other: Egyptian Vultures have gone through extensive population decline, though in some locations the population is more stable now and recovering. They are greatly affected by human activity, including things such as power lines and hunting, intentional poisoning, and superstition-based activity. Since vultures are considered harbingers of doom, people tend to be afraid of them - and they aren’t always the prettiest birds, so people don’t feel emotional attachment to them enough to avoid killing them. Declines in herding and livestock maintenance among humans also has lead to some population decline. Combinations of these factors in many countries make conservation efforts difficult to implement. Some attempts to preserve this vulture have included “vulture restaurants”, where carcasses are made available to vultures nearby.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut

Agarwal, G.P.; Ahmad, Aftab; Arya, Gaurav; Saxena, Renu; Nisar, Arjumand; Saxena, A.K. (2012). "Chaetotaxy of three nymphal instars of an ischnoceran louse, Aegypoecus perspicuus (Phthiraptera: Insecta)". Journal of Applied and Natural Science. 4 (1): 92–95.

Agostini, Nicolantonio; Premuda, Guido; Mellone, Ugo; Panuccio, Michele; Logozzo, Daniela; Bassi, Enrico; Cocchi, Leonardo (2004). "Crossing the sea en route to Africa: Autumn migration of some Accipitriformes over two Central Mediterranean islands". The Ring. 26 (2): 71–78.

Agudo, Rosa; Rico, Ciro; Vilà, Carles; Hiraldo, Fernando; Donázar, José (2010). "The role of humans in the diversification of a threatened island raptor". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 10: 384.

Ali, Sálim; Ripley, Sidney Dillon (1978). Handbook of the birds of India and Pakistan. Volume 1 (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 310–314.

Amadon, D. 1977. Notes on the taxonomy of vultures. Condor 79(4):413-416

Amezian, M.; El Khamlichi, K. (2016). "Significant population of Egyptian Vulture Neophron percnopterus found in Morocco". Ostrich. 87 (1): 73–76.

Angelov, Ivaylo; Hashim, Ibrahim; Oppel, Steffen (2012). "Persistent electrocution mortality of Egyptian Vultures Neophron percnopterus over 28 years in East Africa". Bird Conservation International. 23: 1–6.

Baker, E.C. Stuart (1928). The Fauna of British India. Birds. Volume 5 (2nd ed.). London: Taylor and Francis. pp. 22–24.

Baxter, R. M.; Urban, E. K.; Brown, L. H (1969). "A Nineteenth-century reference to the use of tools by the Egyptian vulture". Journal of the East Africa Natural History Society and National Museum. 27 (3): 231–232.

Biddulph, C.H. (1937). "Unusual site for the nest of the White Scavenger Vulture Neophron percnopterus ginginianus (Lath.)". The Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 39 (3): 635–636.

Byrd, Brooke. "Of Love and Loathing: The Role of the Vulture in Three Cultures". Prized Writing: 81–93.

Carrete, Martina; Sánchez-Zapata, José A.; Benítez, José R.; Lobón, Manuel; Donázar, José A. (2009). "Large scale risk-assessment of wind-farms on population viability of a globally endangered long-lived raptor". Biological Conservation. 142 (12): 2954–2961.

Ceballos, Olga; Donázar, José Antonio (1990). "Roost-tree characteristics, food habits and seasonal abundance of roosting Egyptian Vultures in northern Spain". Journal of Raptor Research. 24 (1–2): 19–25.

Ceballos, Olga; Donázar, José Antonio (1989). "Factors influencing the breeding density and nest-site selection of Egyptian vulture (Neophron percnopterus)". Journal of Ornithology. 130 (3): 353–359.

Clark, William S.; Schmitt, N.J. (1998). "Ageing Egyptian Vultures". Alula. 4: 122–127.

Clements, J. F., T. S. Schulenberg, M. J. Iliff, D. Roberson, T. A. Fredericks, B. L. Sullivan, and C. L. Wood. 2017. The eBird/Clements checklist of birds of the world: v2017

Cortés-Avizanda, A.; Carrete, M.; Serrano, D.; Donázar, J.A. (2009). "Carcasses increase the probability of predation of ground-nesting birds: a caveat regarding the conservation value of vulture restaurants”. Animal Conservation. 12: 85–88.

Cortés-Avizanda, Ainara; Ceballos, Olga; Donázar, José A. (2009). "Long-Term Trends in Population Size and Breeding Success in the Egyptian Vulture (Neophron percnopterus) in Northern Spain". Journal of Raptor Research. 43 (1): 43–49.

Coultas, Harland (1876). Zoology of the Bible. London: Wesleyan Conference Office.

Cuthbert, R.; Green, R.E.; Ranade, S.; Saravanan, S.; Pain, D.J.; Prakash, V.; Cunningham, A.A. (2006). "Rapid population declines of Egyptian vulture (Neophron percnopterus) and red-headed vulture (Sarcogyps calvus) in India". Animal Conservation. 9 (3): 349–354.

Dewar, Douglas (1906). Bombay Ducks. John Lane, London. p. 277.

Donázar, José Antonio; Ceballos, Olga (1989). "Growth rates of nestling Egyptian Vultures Neophron percnopterus in relation to brood size, hatching order and environmental factors". Ardea. 77 (2): 217–226.

Donázar, Jose A.; Ceballos, Olga (1988). "Red fox predation on fledgling Egyptian vultures". Journal of Raptor Research. 22 (3): 88.

Donázar, José Antonio; Ceballos, Olga (1989). "Post-fledging dependence period and development of flight and foraging behaviour in the Egyptian Vulture Neophron percnopterus". Ardea. 78 (3): 387–394.

Donázar, José A.; Ceballos, Olga (1990). "Acquisition of food by fledgling Egyptian Vultures Neophron percnopterus by nest-switching and acceptance by foster adults". Ibis. 132 (4): 603–607.

Donázar, José A.; Ceballos, Olga; Tella, José L. (1994). "Copulation behaviour in the Egyptian Vulture Neophron percnopterus". Bird Study. 41 (1): 37–41.

Donázar, José A.; Ceballos, Olga; Tella, José L. (1996). "Communal roosts of Egyptian vultures (Neophron percnopterus): dynamics and implications for the species conservation". In Muntaner, J. (ed.). Biology and Conservation of Mediterranean Raptors. Monografía SEO-BirdLife, Madrid. pp. 189–201.

Donázar, José A.; Palacios, César J.; Gangoso, Laura; Ceballos, Olga; González, Maria J.; Hiraldo, Fernando (2002). "Conservation status and limiting factors in the endangered population of Egyptian vulture (Neophron percnopterus) in the Canary Islands". Biological Conservation. 107 (1): 89–97.

Donázar, José Antonio; Negro, Juan José; Palacios, César Javier; Gangoso, Laura; Godoy, José Antonio; Ceballos, Olga; Hiraldo, Fernando; Capote, Nieves (2002). "Description of a new subspecies of the Egyptian Vulture (Accipitridae: Neophron percnopterus) from the Canary Islands". Journal of Raptor Research. 36 (1): 17–23.

Elorriaga, Javier; Zuberogoitia, Iñigo; Castillo, Iñaki; Azkona, Ainara; Hidalgo, Sonia; Astorkia, Lander; Ruiz-Moneo, Fernando; Iraeta, Agurtzane (2009). "First Documented Case of Long-Distance Dispersal in the Egyptian Vulture (Neophron percnopterus)". Journal of Raptor Research. 43 (2): 142–145.

Ferguson-Lees, James; Christie, David A. (2001). Raptors of the World. Christopher Helm. pp. 417–420.

Galushin, V.M. (1975). "A comparative analysis of the density of predatory birds in two selected areas within the Palaearctic and Oriental regions, near Moscow and Delhi (IOC Abstracts)". Emu. 74 (5): 331.

Galushin, V. M. (2001). "Populations of vultures and other raptors in Delhi and neighboring areas from 1970's to 1990's". In Parry-Jones, J.; Katzner, T. (eds.). Report from the Workshop on Indian Gyps vultures: 4th Eurasian congress on raptors. Sevilla, Spain: aviary.org. pp. 13–15.

Gangoso, Laura (2005). "Ground nesting by Egyptian Vultures (Neophron percnopterus) in the Canary Islands". Journal of Raptor Research. 39 (2): 186–187.

Gangoso, Laura; Álvarez-Lloret, Pedro; Rodríguez-Navarro, Alejandro A. B.; Mateo, Rafael; Hiraldo, Fernando; Donázar, José Antonio (2009). "Long-term effects of lead poisoning on bone mineralization in vultures exposed to ammunition sources". Environmental Pollution. 157 (2): 569–574.

García-Ripollés, Clara; López-López, Pascual (2006). Penteriani, Vincenzo (ed.). "Population size and breeding performance of Egyptian vultures (Neophron percnopterus) in eastern Iberian Peninsula". Journal of Raptor Research. 40 (3): 217–221.

García-Ripollés, Clara; López-López, Pascual; Urios, Vicente (2010). "First description of migration and wintering of adult Egyptian Vultures Neophron percnopterus tracked by GPS satellite telemetry". Bird Study. 57 (2): 261–265.

Grande, Juan M.; Serrano, David; Tavecchia, Giacomo; Carrete, Martina; Ceballos, Olga; Díaz-Delgado, Ricardo; Tella, José L.; Donázar, José A. (2009). "Survival in a long-lived territorial migrant: effects of life-history traits and ecological conditions in wintering and breeding areas". Oikos. 118 (4): 580–590.

Grimal, Pierre (1996). The dictionary of classical mythology. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 18.

Hartert, Ernst (1920). Die Vögel der paläarktischen Fauna. Volume 2. Berlin: Friendlander & Sohn. pp. 1200–1202.

Hernández, Mauro; Margalida, Antoni (2009). "Poison-related mortality effects in the endangered Egyptian vulture (Neophron percnopterus) population in Spain". European Journal of Wildlife Research. 55 (4): 415–423.

Hertel, Fritz (1995). "Ecomorphological indicators of feeding behavior in recent and fossil raptors". The Auk. 112 (4): 890–903.

Hidalgo, S.; Zabala, J.; Zubergoitia, I.; Azkona, A.; Castillo, I. (2005). "Food of the Egyptian vulture (Neophron percnopterus) in Biscay". Buteo. 14: 23–29.

Ingerson, Ernest (1923). Birds in legend, fable and folklore. New York: Longmans, Green and Co.

Jardine, William; Selby, Prideaux John (1826). Illustrations of ornithology. Volume 1. Edinburgh: W.H. Lizars.

Jaume, D., M. McMinn, and J. A. Alcover. 1993. Fossil birds from the Bujero del Silo, La Gomera (Canary Islands), with a description of a new species of quail (Galliformes: Phasianidae). Boletim do Museu Municipal do Funchal 2:147-165

Jobling, J. A. 2010. The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. Christopher Helm Publishing, A&C Black Publishers Ltd, London.

Koenig, Alexander (1907). "Die Geier Aegyptens" [The Egyptian vulture]. Journal für Ornithologie (in German). 55: 59–134.

Kretzmann, Maria B.; Capote, N.; Gautschi, B.; Godoy, J.A.; Donázar, J.A.; Negro, J.J. (2003). "Genetically distinct island populations of the Egyptian vulture (Neophron percnopterus)". Conservation Genetics. 4 (6): 697–706.

Latham, John (1787). Supplement to the General Synopsis of birds. London: Leigh & Sotheby. p. 7.

Liberatori, Fabio; Penteriani, Vincenzo (2001). "A long-term analysis of the declining population of the Egyptian vulture in the Italian peninsula: distribution, habitat preference, productivity and conservation implications". Biological Conservation. 101 (3): 381–389.

Linnaeus, C. 1758. Systema Naturae per Regna Tria Naturae, Secundum Classes, Ordines, Genera, Species, cum Characteribus, Differentiis, Synonymis, Locis. Editio Decima 1:1-824

Margalida, A.; Benítez, J.R.; Sánchez-Zapata, J.A.; Ávila, E.; Arenas, R.; Donázar, J.A. (2012). "Long-term relationship between diet breadth and breeding success in a declining population of Egyptian Vultures Neophron percnopterus". Ibis. 154: 184–188.

Margalida, Antoni; Boudet, Jennifer (2003). "Dynamics and temporal variation in age structure at a communal roost of egyptian vultures (Neophron percnopterus) in northeastern Spain". Journal of Raptor Research. 37 (3): 252–256.

Peters, James L. (1979). Mayr, Ernst; Cottrell, G.W. (eds.). Check-list of birds of the world. Volume 1 (2nd ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Museum of Comparative Zoology. p. 304.

Mateo, Patricia; Olea, Pedro P. (2007). "Egyptian Vultures (Neophron percnopterus) Attack Golden Eagles (Aquila chrysaetos) to Defend their Fledgling". Journal of Raptor Research. 41 (4): 339–340.

Meyburg, Bernd-U.; Gallardo, Max; Meyburg, Christiane; Dimitrova, Elena (2004). "Migrations and sojourn in Africa of Egyptian vultures (Neophron percnopterus) tracked by satellite". Journal of Ornithology. 145 (4): 273–280.

Mundy, P.J. (1978). "The Egyptian vulture (Neophron Percnopterus) in Southern Africa". Biological Conservation. 14 (4): 307–315.

Neelakantan, K.K. (1977). "The sacred birds of Thirukkalukundram". Newsletter for Birdwatchers. 17 (4): 6.

Negro, J.J.; Grande, J.M.; Tella, J.L.; Garrido, J.; Hornero, D.; Donázar, J.A.; Sanchez-Zapata, J.A.; Benítez, J.R.; Barcell, M. (2002). "Coprophagy: An unusual source of essential carotenoids". Nature. 416 (6883): 807–808.

Orta, J., Kirwan, G.M., Christie, D.A., Garcia, E.F.J. & Marks, J.S. (2019). Egyptian Vulture (Neophron percnopterus). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Palacios, César-Javier (2004). "Current status and distribution of birds of prey in the Canary Islands". Bird Conservation International. 14 (3).

Palacios, César-Javier (2000). "Decline of the Egyptian vulture (Neophron percnopterus) in the Canary Islands". Journal of Raptor Research. 34 (1): 61.

Paynter, W.P. (1924). "Lesser White Scavenger Vulture N. ginginianus nesting on the ground". The Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 30 (1): 224–225.

Pope, G.U. (1900). The Tiruvacagam or Sacred utterances of the Tamil poet, saint, and sage Manikka-vacagar. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Prakash, Vibhu; Nanjappa, C. (1988). "An instance of active predation by Scavenger Vulture (Neophron p. ginginianus) on Checkered Keelback watersnake (Xenochrophis piscator) in Keoladeo National Park, Bharatpur, Rajasthan". The Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 85 (2): 419.

Rasmussen, P.C.; Anderton, J.C. (2005). Birds of South Asia: The Ripley Guide. Volume 2. Smithsonian Institution and Lynx Edicions. p. 89.

Seibold, I.; Helbig, A.J. (1995). "Evolutionary History of New and Old World Vultures Inferred from Nucleotide Sequences of the Mitochondrial Cytochrome b Gene". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 350 (1332): 163–178.

Siromoney, Gift (1977). "The Neophron Vultures of Thirukkalukundram". Newsletter for Birdwatchers. 17 (6): 1–4.

Spaar, Reto (1997). "Flight strategies of migrating raptors; a comparative study of interspecific variation in flight characteristics". Ibis. 139 (3): 523–535.

Stoyanova, Yva; Stefanov, Nikolai (1993). "Predation upon nestling Egyptian Vultures (Neophron percnopterus) in the Vratsa Mountains of Bulgaria". Journal of Raptor Research. 27 (2): 123.

Stoyanova, Yva; Stefanov, Nikolai; Schmutz, Josef K. (2010). "Twig Used as a Tool by the Egyptian Vulture (Neophron percnopterus)". Journal of Raptor Research. 44 (2): 154–156.

Suárez-Pérez, A.; Ramírez, A.S.; Rosales, R.S.; Calabuig, P.; Poveda, C.; Rosselló-Móra, R.; Nicholas, R.A.J.; Poveda, J.B. (2012). "Mycoplasma neophronis sp. nov., isolated from the upper respiratory tract of Canarian Egyptian vultures (Neophron percnopterus majorensis)". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 62 (Pt 6): 1321–1325.

Stratton-Porter, Gene (1909). Birds of the Bible. Cincinnati: Jennings and Graham. p. 182.

Tauler-Ametller, H.; Hernández-Matías, A.; Pretus, J. L.L.; Real, J. (2017). "Landfills determine the distribution of an expanding breeding population of the endangered Egyptian Vulture Neophron percnopterus". Ibis. 159 (4): 757–768.

Tella, José Luis (1993). "Polyandrous trios in a population of Egyptian vultures (Neophron percnopterus)". Journal of Raptor Research. 27 (2): 119–120.

Tella, José L.; Mañosa, Santi (1993). "Eagle owl predation on Egyptian vulture and northern goshawk: possible effect of a decrease in European rabbit availability". Journal of Raptor Research. 27 (2): 111–112.

Thompson, D'Arcy Wentworth (1895). A glossary of Greek birds. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Thouless, C.R.; Fanshawe, J.H.; Bertram, B.C.R. (1989). "Egyptian Vultures Neophron percnopterus and Ostrich Struthio camelus eggs: The origins of stone-throwing behaviour". Ibis. 131: 9–15.

Thurston, E.W. (1906). Ethnographic notes in southern India. Madras: Government Press.

van Lawick-Goodall, Jane; van Lawick, Hugo (1966). "Use of Tools by the Egyptian Vulture, Neophron percnopterus". Nature. 212 (5069): 1468–1469.

van Overveld, T.; de la Riva, M.; Donázar, J. A. (2017). "Cosmetic coloration in Egyptian vultures: Mud bathing as a tool for social communication?". Ecology. 98 (8): 2216–2218.

Whistler, Hugh (1949). Popular Handbook of Indian Birds (4th ed.). London: Gurney & Jackson. pp. 356–357.

Whistler, Hugh (1922). "The birds of Jhang district, S.W.Punjab. Part II. Non-Passerine birds". Ibis. 64 (3): 401–437.

Wink, Michael (1995). "Phylogeny of Old and New World Vultures (Aves: Accipitridae and Cathartidae) Inferred from Nucleotide Sequences of the Mitochondrial Cytochrome b Gene". Zeitschrift für Naturforschung C. 50 (11/12): 868–882.

Wink, Michael; Heidrich, Petra; Fentzloff, Claus (1996). "A mtDNA phylogeny of sea eagles (genus Haliaeetus) based on nucleotide sequences of the cytochrome b-gene". Biochemical Systematics and Ecology. 24 (7–8): 783–791.

Yosef, Reuven; Alon, Dan (1997). "Do immature Palearctic Egyptian Vultures Neophron percnopterus remain in Africa during the northern summer?". Vogelwelt. 118: 285–289.

Zarudny, V.; Härms, M. (1902). "Neue Vogelarten". Ornithologische Monatsberichte (in German) (4): 49–55.

#Neophron percnopterus#Neophron#Vulture#Egyptian Vulture#Dinosaur#Dinosaurs#Bird of Prey#Bird#Birds#Raptor#Pharaoh's Chicken#White Scavenger Vulture#Quaternary#Eurasia#Africa#India & Madagascar#Carnivore#Theropod Thursday#Accipitrimorph#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature#factfile#birblr

184 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Teratornis, by Nobu Tamura, CC BY 3.0

#teratornis#accipitrimorph#afroavian#inopinavian#neoavian#neognath#neornithine#euornithine#avialan#paravian#maniraptoran#coelurosaur#theropod#tetanuran#cenozoic#quaternary#pleistocene#tarantian#calabrian#north america#extinct#reconstruction

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

For the accipitrimorphs group I'd like to encourage you all to vote for the teratorns! Why, you ask? Because they were huge and carrion-feeders were awesome (and I think we need to steal Argentavis' fame back from ARK) Vote teratorns!

50 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Eastern Screech Owl, Megascops asio, post exemplifying how great material is ruined by minimal equipment, but even more so by a false sense of urgency. We found this fledgling struggling to scale a tree back in May and after Skyla caught them I had plenty of time to take an actually focused picture with my macro friendly macro phone camera. I just, uh, didnt. But anyway, you can observe some nervous 'clacking' from this still very downy individual (its adult contours have not yet grown in to cover the body despite its seemingly developed remiges) and a rufous morph fly past us. The group observed had at least 2 grey and 1 rufous adults, but one of these greys might (probably) also have been a fledgling figuring out arboreal...uh -ness like this one. Again, dont know why I didnt record but we released this one on a branch of the same tree and they seemed to have greater ease in short flight between trees with their "group." Unlike most birds, but like most Strigiformes, M. asio are predominantly solitary, only forming temporary breeding pair in the winter, so I was surprised to see the parents still with the chicks this late in spring (and active in late afternoon). The final video is a late night call from the same neighborhood but from July. I walked outside and caught a glimpse of a grey bird with low aspect wings (short&broad) flying after the calls stopped. Same ind? The Order Strigiformes is closely related to Accipitrimorph raptors sitting just a step down in the Afroavian clade. Mousbirds are just past that but are more morphological and ecologically distant than owls and the accipitrimorphs, so I'd hazard a guess their genetics similarly align. Strigiformes contains two extant Families, Tytonidae or Barn Owls, and Strigidae or all other Owls. There is a relatively meaty fossil record of owls but idk anything about anything, as you know, so I'm going gloss over that and just invite you to check out the wiki art for the early Cenozoic Sophiornithidae, a reconstruction of which I promised my brother, but never actually finished because I lack moral fiber. #raptor #owl #virginia #birdofprey #nocturnal #strigiformes #strigidae #nature #bird #Megascops (at Virginia Beach, Virginia) https://www.instagram.com/p/B165Ww1A2At/?igshid=v1kgx0o0te7h

0 notes

Photo

The most basic guide to Neornithes, aka Modern Birds

Everything is as simplified as possible. Based on Prum et al., 2015. Note some things:

1) All names here are of the groups used in Dinosaur March Madness (as a guide), and the relevant parent clades

2) According to Prum’s analysis, Camprimulgiformes are actually paraphyletic with regards to Apodiformes, i.e., Apodiformes should really be within Caprimulgiformes, but since this is a relatively controversial conclusion, I’ve left them separate for now

3) Aequorlitornithes is a ridiculously long clade name.

4) The classic clade of Afroaves was not, in fact, recovered; rather, Accipitrimorphs were found as being less closely related to Australaves than Strigiformes and Coraciimorphs were. Traditionally, Telluraves was divided directly in half: Afroaves (Accipitrimorphs, Strigiformes, and Coraciimorphs) and Australaves (Cariamiformes, Falconfiromes, Parrots and Passerines). Here, Accipitrimorphs falls outside of [Strigiformes + Coraciimorphs] + Australaves.

5) This doesn’t really take into account fossil taxa or morphological data.

6) Bird phylogeny is in flux. I doubtlessly will make more of these.

Source: Prum, R. O., J. S. Berv, A. Dornburg, D. J. Field, J. P. Townsend, E. M. Lemmon, A. R. Lemmon. 2015. A comprehensive phylogeny of birds (Aves) using targeted next-generation DNA sequencing. Nature 526: 569 - 573.

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

Micronisus gabar

By Lip Kee, CC BY-SA 2.0

Etymology: Small Sparrowhawk

First Described By: Gray, 1840

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Inopinaves, Telluraves, Afroaves, Accipitrimorphae, Accipitriformes, Accipitridae, Melieraxinae

Status: Extant, Least Concern

Time and Place: 10,000 years ago, in the Holocene of the Quaternary

The Gabar Goshawk is known from most of sub-Saharan Africa, apart from the densest rainforest

Physical Description: Gabar Goshawks are small birds of prey, coming in two main morphs of colors - some are dark all over, with dark banding on their tails; while others are grey, with that same dark banding on its tail. The females are larger than the males, and they range between 28 and 36 centimeters long. Their feet have long claws and are orange, and they have short, curved beaks that are orange with black tips. So, in a lot of ways, they are somewhat Halloween themed birds of prey! The sexes tend to look the same. They also have white patches on their wings, most of the time. The juveniles tend to be brown, with streaks across their chests.

Diet: Gabar Goshawks feed mainly on other birds! Primarily, small birds such as guineafowl, coucals, and francolins. They also eat small reptiles and some small mammals - including bats!

By Bernard DuPont, CC By-SA 2.0

Behavior: The Gabar Goshawks will spend a decent amount of time actively pursuing prey, diving through the air to catch the flighted animals after which it chases. It will sometimes also wait in trees, or go into nests in order to get food - taking dozens of animals from sites at a time and bringing them back to their nests. It will hunt mainly in places of cover, sometimes in pairs, and sometimes with the help of falcons. They’ll tear into nests, grabbing whatever they can to devour the food inside. They are fairly silent birds, only making piping noises from perches when displaying to each other. These piping calls will also be made when feeding young - and when the young are asking for food.

Gabar Goshawks don’t migrate, but they do tend to move locally based on the dry season, and juveniles are a little nomadic and move in response to food. They tend to lay eggs at the end of the dry season, sometimes even breeding twice a year. The couple will do circles in the air around each other, and call to each other as a part of their mating rituals. They build nests together out of sticks in thorny trees, using earth and rootlets to bind the nest together. These nests are usually quite high off of the ground, and they’ll even have intentional spiderwebs on top to conceal the eggs. Two eggs are usually laid, and incubated for a little more than a month by the female; the male will help bring her food. The chicks are very white and fluffy, growing less and less white as they age. They fledge after another month or so, and tend to become more independent at that point.

By Lip Kee, CC BY-SA 2.0

Ecosystem: As indicated by their distribution, Gabar Goshawks live primarily in open thorn savannah and in some more open woodland habitats. They are preyed upon by tawny eagles, Wahlberg’s Eagle, and Ayres’ Hawk-Eagle.

Other: Thankfully, Gabar Goshawks are not threatened with extinction. They are common and widespread in a grand variety of habitats. Their range is even expanding, and in recent years they’ve been found in new locations outside of their natural range. There are some places where they are scarce, but by and large they are very common. They are brave birds, colonizing urban areas, though they are sometimes hunted by people due to being perceived as a threat (though they’re too small to be a problem for poultry!)

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut

Jobling, J. A. 2010. The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. Christopher Helm Publishing, A&C Black Publishers Ltd, London.

Kemp, A.C. & Kirwan, G.M. (2019). Gabar Goshawk (Micronisus gabar). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

#Micronisus gabar#Micronisus#Gabar Goshawk#Bird#Dinosaur#Raptor#Bird of Prey#Birblr#Factfile#Goshawk#Accipitrimorph#Quaternary#Africa#Theropod Thursday#Carnivore

153 notes

·

View notes

Text

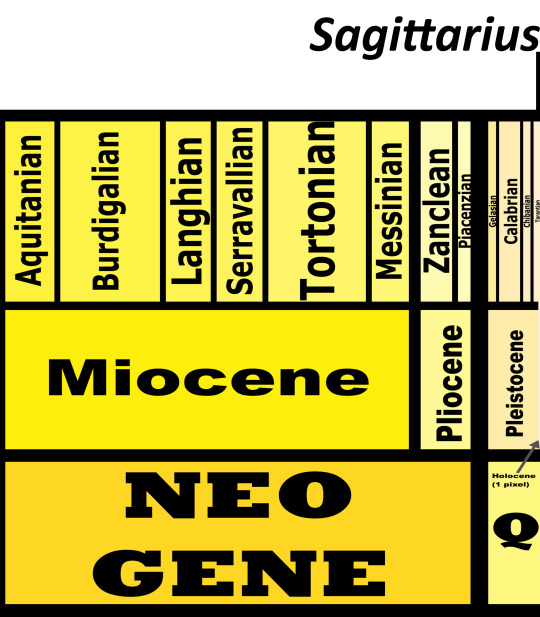

Sagittarius serpentarius

By Ikiwaner, GFDL 1.2

Etymology: Archer

First Described By: Hermann, 1783

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Inopinaves, Telluraves, Afroaves, Accipitrimorphae, Accipitriformes, Sagittariidae

Status: Extant, Vulnerable

Time and Place: Within the last 10,000 years, in the Holocene of the Quaternary

The Secretarybird is known from a variety of arid (re: non-dense tropical rainforests) across sub-Saharan Africa

Physical Description: Secretarybirds are among the most visually distinctive of living dinosaurs, and one of the species usually pointed to by people attempting to prove the dinosaur nature of birds via visual evidence. These are large raptors, with extremely long and thin legs like those of storks. They have sharp talons on their feet, and they are truly living the “Velociraptor is my great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great auntie and I’m here to kick your ass” life.

They still have the ability to fly, with large wings and elongated bodies - including long, stiffened tail feathers just to add to the whole “wait if I squint maybe it has a bony tail like a Velociraptor” appearance it has going on. It has a medium-length neck, with a small head and a distinctive crest of thin feathers off the back of its head. It also has a downward-curved, sharp beak.

By Lip Kee Yap, CC BY-SA 2.0

In terms of color, the Secretarybirds have orange patches over their eyes, and mainly white heads besides; the ends of their crest feathers are black. Their leg feathers are black too, as are some of their rump feathers, the tips of their wings, their backs, and the ends of their tails. The males and females look roughly the same, with the females somewhat smaller than the males. In general, they range between 125 and 150 centimeters in length. Juveniles are very similar to the adults, but with shorter crests and tails. In short, these are raptors that aren’t actually mistaken for other raptors - but might be mistaken for cranes!

The Secretarybird is interesting on the inside as well - it has a very short digestive tract, and a foregut highly specialized for digesting large quantities of meat very quickly. They don’t have a muscular gizzard like other birds, and they don’t have any fermentation agents since they don’t eat plants at all!

By Biran Ralphs, CC BY 2.0

Diet: Though it can fly, the Secretarybird does the entirety of its hunting on the ground, stalking through the grass to catch a variety of meat prey including mammals as big as mongooses, lizards, snakes, tortoises, other birds, eggs, crabs, and insects. They do kill even bigger mammals like young gazelles and cheetah cubs. In short, they’re making their ancestors proud.

Behavior: Secretarybirds have a lot of very distinctive behaviors that make them iconic, bird-wise, among the masses. Most especially, they engage in very fast kicking with their long legs in order to grab prey - evoking images of dinosaurs gone by. These kicks are fast, powerful, and terrifying - and then on top of that insanity, they swallow their food whole with their large, gaping beaks! To get their food out of hiding, they even stomp incessantly on the ground in order to flush it out. They usually only tear up their food with their toes while holding it down, not bothering to chop it up with their beaks. Sometimes they’ll even jump down onto food, using a little bit of raptor-prey-restraint or lift with their wings to get the jump on their prey. These birds usually hunt alone, or with their mate nearby.

youtube

These birds do not migrate much, but they can be nomadic in response to rainfall and fires. The juveniles especially travel far in search of areas unoccupied by mated pairs. They make high pitched, “ko-ko-ko-ko-ko-ka” calls to one another, in addition to more “kowaaaaaaa kowaaaaaaaa” and “kurrk-urr-kurrk-urr” calls back and forth. They aren’t actually that good at running, despite their long legs - they instead are really only good for the stomp-strike they use for hunting.

By Donald Macauley, CC BY-SA 2.0

These birds form monogamous pairs, that stay together for most of their lives. They have an elaborate courtship display for one another that involves soaring high and flying in an undulated fashion around each other, and croaking at each other. Sometimes they also will court each other on the ground, chasing each other with their wings up like how they chase prey. They will nest any time of the year, usually corresponding to abundance of food. They especially raise chicks in the rainy system. Their nests are made fairly high up in Acacia trees, made out of sticks with dense grass and wool lining, usually made in the shape of a saucer. THey lay between 1 and 3 eggs in a nest, which are incubated by both parents for about a month and a half. The chicks are pale grey and fluffy with short, straight bills; they moult twice before reaching a juvenile plumage at six weeks. They are dependent on their parents for over three months; their parents will eat insects and then regurgitate them back into the young’s mouths. The parents teach their young how to hunt extensively, in order for them to be independent by the end of their rearing period.

By Kore, CC BY-SA 3.0

Ecosystem: Secretarybirds live in steppes and savanna, especially enjoying short grasses with scattered trees for roosting and nesting. They rarely go anywhere with more trees. They can be found at a variety of elevations. Here they live with a wide variety of animals, especially venomous snakes, which they are famous for eating. However, their own young are fed upon by crows, ravens, hornbills, kites, and owls.

Other: Secretarybirds are considered vulnerable to extinction, mainly due to extensive habitat loss and rising CO2 levels. These birds are still widespread across Africa and are becoming adapted to more arid, desert-like habitats, but despite this common nature of the species they are still listed as vulnerable due to a recent rapid decline across the entirety of their range. They are a very revered bird in Africa, used as the emblem of Sudan and a motif on postage stamps - though they are also called the Devil’s Horse!

By Yoky, CC BY-SA 3.0

As to the peculiar name, some think it is because the crest feathers look like quill feathers for a pen, leading to the association with a secretary - but this hypothesis has fallen out of favor. Some may think it is a mishearing of the French “Saqr-et-tair”, aka, hunter bird. Either way, the quills also look like a quiver of arrows - and it is a skilled hunter - leading to its genus name being Sagittarius, aka, Archer!

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Allan, D.G.; Harrison, J.A.; Navarro, R.A.; van Wilgen, B.W.; Thompson, M.W. (1997). "The Impact of Commercial Afforestation on Bird Population in Mpumalanga Province, South Africa – Insights from Bird-Atlas Data". Biological Conservation. 79 (2–3): 173–185.

Jobling, J. A. 2010. The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. Christopher Helm Publishing, A&C Black Publishers Ltd, London.

Kemp, A.C. (2019). Secretarybird (Sagittariidae). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Kemp, A.C., Kirwan, G.M., Christie, D.A. & Marks, J.S. (2019). Secretarybird (Sagittarius serpentarius). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Maloiy, G. M. O.; Alexander, R. M. C. N.; Njau, R.; Jayes, A. S. (1979). "Allometry of the legs of running birds". Journal of Zoology. 187 (2): 161–167.

Mayr, G.; Clarke, J. (2003). "The deep divergences of neornithine birds: a phylogenetic analysis of morphological characters". Cladistics. 19 (6): 527–553.

Scharning, Kjell. "Secretary Bird Sagittarius serpentarius". Theme Birds on Stamps. Archived from the original on 18 January 2018.

Sherman, Patrick (2007). "Sagittarius serpentarius : secretary bird". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology.

Simmons, R.E. (2015). "Secretarybird – Sagittarius serpentarius". In R.E. Simmons; C.J. Brown; J. Kemper (eds.). Bird to watch in Namibia – red, rare and endangered species. Namibian Ministry of Environment and Tourism, and the Namibia Nature Foundation.

Todd, William T. (1988). "Hand-Rearing the Secretary Bird Sagitarius Serpentarius at Oklahoma City Zoo". International Zoo Yearbook. 27 (1): 258–263.

#Sagittarius serpentarius#Secretarybird#Sagittarius#bird#Dinosaur#Birblr#Factfile#Bird of Prey#Raptor#Secretary Bird#Dinosaurs#Birds#Quaternary#Africa#Theropod Thursday#Carnivore#Accipitrimorph#prehistoric life#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

394 notes

·

View notes

Text

Torgos tracheliotos

By Steve Garvie, CC BY-SA 2.0

Etymology: Vulture

First Described By: Kaup, 1828

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Inopinaves, Telluraves, Afroaves, Accipitrimorphae, Accipitriformes, Accipitridae

Status: Extant, Endangered

Time and Place: In the last 10,000 years, in the Holocene of the Quaternary

The Lappet-Faced Vulture is known from arid locations around Africa and the Arabian Peninsula

Physical Description: Lappet-Faced Vultures are fairly typical looking vultures, and ginormous birds too - ranging up to 115 centimeters in body length, with 280 centimeter long wingspans. They are brown all over their backs and wings with white bellies and legs, and they have naked heads (as many vultures do). This distinctive contrast in feather color makes the Lappet-Faced Vulture fairly easy to spot! These heads can be pink or brown, depending on the sub-population. They have bulky, sharp clawed feet, and very large hooked beaks. The juveniles are also brown, and still have some feathery down on their heads unlike the bare-headed adults.

Diet: These vultures - like most vultures - eat primarily carrion, including both large and small carcasses. They do occasionally hunt for their own food, but more than that they’ll take fresh food caught by other raptors like eagles.

By Chris Eason, CC BY 2.09

Behavior: These birds will make groups of large numbers of vultures, of multiple species, gathering at carcasses or sources of food, pulling off food from the carcass including the skin and bones. They will soar low and slowly over wide areas while looking for food, able to cover large distances with low energy through their large and broad wings. They have poor senses of smell, unlike other vultures, and so mainly rely on hearing and sight in order to find carcasses. They do interact with each other while feeding, fighting and arguing over carcasses - but other than that, the Lappet-Faced Vulture tends to stay silent and solitary while on the move, only making some hisses and chattering while at carcasses and at the nest. They only migrate due to the changing in rain and dry season, though they do have very large territories in which they search for food.

By Dominic Sherony, CC BY-SA 2.0

Unlike other vultures, the Lappet-Faced vulture does not partake in communal roosts. Instead, they nest alone, though pairs can clump a little within an area with suitable nesting sites. They make a platform of sticks, lined with dry grass, placed on exposed trees like the Acacia trees. They lay their eggs usually in the dry season, laying only one egg per nest that incubates for nearly two months of time. The chicks are then fluffy and white, becoming grey after moulting, and fledge after more than four months. The parents will take care of the young together, even though the young are dependent on the parents for such a long time. The young will stay near the parents for an entire year before going out on their own, and they are not sexually mature until six years of age. It is uncertain if the adults form lifelong pair bonds, or just seasonal pair bonds.

Ecosystem: Lappet-Faced Vultures live in steppe and desert habitats, and do verge into open savanna and arid plains. They are occasionally found in mountain slopes as well, and along the edges of forests. They have no major predators other than humans, but have been known to be the victims of nest parasitism.

By Yathin sk, CC BY-SA 3.0

Other: Lappet-Faced Vultures have a very small and rapidly declining population, entirely threatened due to human activity. They are scattered across huge, disconnected ranges, with low density in each range. Habitat disturbance, human cultivation, nesting site disturbance, pesticides, and hunting all threaten these populations - humans tend to kill these birds without question and without qualm. They were only listed as vulnerable recently, too, and the plight of the Lappet-Faced Vulture only recently made news on a global scale. They tend to be killed and chased off from cattle carcasses, for example, even though they rely on them for food. On estimation, there are probably less than 9,000 of these beautiful birds left in the world - but, because they’re “ugly vultures”, no one seems to care. Legislation over pesticides is ongoing, and there are breeding programs active in Israel, but there is very little research or ongoing programs to protect these wonderful birds.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Ferguson-Lees, James and Christie, David A. (2001) Raptors of the World. Houghton Mifflin Company, ISBN 978-0-618-12762-7.

Hardy, Eric (1947). "The Northern Lappet-faced Vulture in Palestine—A new record for Asia" (PDF). Auk. 64 (3): 471–472.

Jobling, J. A. 2010. The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. Christopher Helm Publishing, A&C Black Publishers Ltd, London.

Kemp, A.C., Christie, D.A. & Sharpe, C.J. (2019). Lappet-faced Vulture (Torgos tracheliotos). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

#Torgos tracheliotos#Torgos#Lappet-Faced Vulture#Vulture#Dinosaur#Birds#Bird#Dinosaurs#Raptor#Accipitrimorph#Birblr#Factfile#Carnivore#Africa#eurasia#Quaternary#Theropod Thursday#Bird of Prey#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

264 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chondrohierax

Hook-Billed Kite by Hector Bottai, CC BY-SA 3.0

Etymology: Coarse Hawk

First Described By: Lesson, 1843

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Inopinaves, Telluraves, Afroaves, Accipitrimorphae, Accipitriformes, Accipitridae,

Referred Species: C. uncinatus (Hook-Billed Kite), C. wilsonii (Cuban Kite)

Status: Extant, Critically Endangered - Least Concern

Time and Place: Within the last 10,000 years, in the Holocene of the Quaternary

The Hook-billed Kites are known from Cuba, Central, and South America, primarily in more humid habitats such as the Amazon basin

Physical Description: These kites range from 38 to 51 centimeters in length, making them fairly large for flighted birds (but not the largest amongst birds of prey by any means, in that respect they’re middle-of-the-road). They are named for their most distinctive feature - a large, heavy, hooked bill. This bill goes well over the underbill, though it varies extensively across individuals in this genus. The birds have strong feet with sharply curved claws, and somewhat short tails. Their wings are ovular in shape, and interestingly enough the females have more interesting color schemes than the males - while all have grey heads with yellow eye patches, the females have brown backs and reddish-brown stripes across their white bellies, while males continue to be grey, with grey stripes. Some morphs of this genus are very dark in color all over. The juveniles are typically dark brown on top and white underneath, with very few stripes.

Diet: These birds feed primarily on tree snails, interestingly enough, which they break apart with their strong beaks. They also will eat some reptiles, frogs, salamanders, craps, and insects, depending on where they live and the food available in that local.

Hook-Billed Kite by Cláudio Dias Timm

Behavior: These are fairly sluggish raptors, all things considered, spending most of their time in the leafy canopy when not flying around. They do fly extensively, though, and are often seen soaring above the rainforest. They will fly until they find a suitable patch of rainforest, go down into the undergrowth, find a snail in its shell, and break the inner whorls of the shell by cracking it with its beak towards the apex of the spire. It will also swallow some smaller snails whole. It will also sit in a perch in the lower canopy to look for snails, or hop between trees. It usually hunts throughout the day, especially during the nesting season. Fairly silent birds, they only tend to make musical chuckling calls to their mate while perched and flying together. They will also make shrill alarm screams in response to danger, and chattering noises to their babies.

When it comes to breeding, they tend to breed whenever the rainy season starts, based on their individual locations. The two birds will circle each other in courtship, low above the canopy, making those noticeable laughing calls. They then build a flimsy stick nest together, between five and seven meters up in the trees or close to the top of the trees - usually precariously placed on thin branches away from the trunk. They lay up to three eggs, usually two, which are incubated for a little over a month. The male will bring food to the female while she incubates, but when the eggs hatch both parents will feed the young. The chicks then fledge in the early to middle rainy season to take advantage of more plentiful snails. These birds are fairly nomadic - with no distinct migratory pattern, they will move in response to availability of food.

Hook-Billed Kites by Mike Ostrowski, CC BY-SA 2.0

Ecosystem: Hook-Billed Kites will live primarily in rainforests, especially in lower canopies and dense understory, as well as in more temperate zones in the Andes mountains. They can also be found in forest edges and clearings, and while they can get up to higher elevations in the Amazon, they are found in lower elevations in more northern locals. The Cuban Kite will be found in more montane gallery forest with extremely tall trees. The young tend to be preyed upon by jays, but the adults don’t have many predators.

Other: These birds are usually very common, but the Cuban species is very much threatened with extinction due to a limited habitat and excessive human hunting. The mainland species may be rarer in some regions, but overall very common and extending its range northward in response to climate change.

Species Differences: The Hook-Billed Kites, as opposed to the Cuban Kites, have dark bills with only slight yellow patches on the lower bill. Meanwhile, the beaks of Cuban Kites are entirely yellow. The Cuban Kite has a much more limited range (in Cuba only), while Hook-Billed Kites are found all over Central and South America. This limited range, in addition to persecution by humans, has led to the critical endangerment of the Cuban Kites.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Bierregaard, R.O., Jr, Kirwan, G.M. & Marks, J.S. (2019). Hook-billed Kite (Chondrohierax uncinatus). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Bond, James (1999). A Field Guide to the Birds of the West Indies. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 55.

del Hoyo, J., Collar, N., Marks, J.S. & Sharpe, C.J. (2019). Cuban Kite (Chondrohierax wilsonii). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Johnson, Jeff A.; Thorstrom, Russell; Mindell, David P. (2007). "Systematics and conservation of the hook-billed kite including the island taxa from Cuba and Grenada" (PDF). Animal Conservation. 10: 349–359.

#Chondrohierax#Hook-Billed Kite#Kite#Dinosaur#Raptor#Bird of Prey#Dinosaurs#Birds#Bird#Birblr#Cuban Kite#Chondrohierax uncinatus#Chondrohierax wilsonii#Accipitrimorph#Theropod Thursday#Carnivore#North America#South America#Quaternary#Factfile#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

115 notes

·

View notes

Text

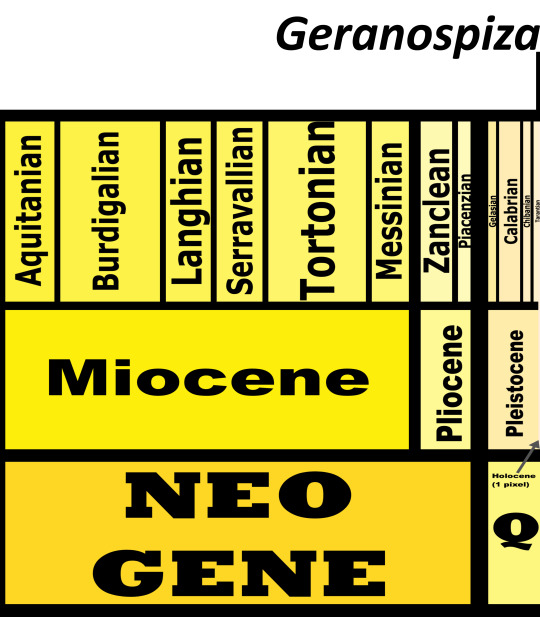

Geranospiza caerulescens

By Jaimoreira Fotografia, CC BY-SA 4.0

Etymology: Crane Hawk

First Described By: Kaup, 1847

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Inopinaves, Telluraves, Afroaves, Accipitrimorphae, Accipitriformes, Accipitridae, Buteoninae

Status: Extant, Least Concern

Time and Place: Within the last 10,000 years, in the Holocene of the Quaternary

The Crane Hawk is known from Central and South America

Physical Description: The Crane Hawk is a distinctive bird, extremely different in silhouette from other birds of prey. It doesn’t have short, stocky legs and thick toe talons - instead, it has long, thin legs, with thin toes and thin talons. Hence its name - the crane hawk - as its legs look like those of a crane. In general it has a stocky body, with long tail feathers, and a small but distinctive head. The beak is sharp, but curved distinctly downward. There are many varieties of this bird - all have orange legs and black and white striped tails. However, two subspecies are grey in color, while the third is black in color. Of the two grey subspecies, one has light banding on its belly, while the other is just pure grey. Juveniles are usually brown with white-streaked heads. The sexes tend to look roughly the same. These birds range from 38 to 54 centimeters in body length.

Diet: The Crane Hawk is a jack-of-all-trades, food wise, feeding on a ridiculously large number of things. The Crane Hawk will eat rodents, bats, lizards, snakes, frogs, birds, bugs, molluscs, and even fruit from time to time.

By Lip Kee, CC BY-SA 2.0

Behavior: Crane Hawks spend most of their time clinging to tree trunks, reaching with its double-jointed legs to grab food from tree hollows. They also use these ridiculously long legs to reach into tightly backed leaves, and even to hang upside down to find food underneath branches. They drop from trees while hanging upside down, to catch prey left on the ground. These hawks also catch food while flying, ducking down low to catch food while flying. Crane Hawks do make contact calls to one another, especially in the early morning, and they sound like “whee-oo-whee-o-whee-o.” They make nasal, drawn-out screams as well, and even more mellow whistles. They don’t migrate, but they are somewhat nomatic back and forth across their range.

By Diver Dave, CC BY-SA 4.0

As for breeding, they start nesting depending on the location - some start as early as April, others start as late as July. The pair have very vocal courtships, with aerial displays and feeding each other prior to mating. They make nests in the form of small and shallow cups with sticks and vines, lined with grass and weeds. They are usually placed up to 15 meters tall in trees, sometimes even higher up. Both parents will construct the nest, and they’ll even share and swap nests with Bicolored Hawks. They lay two eggs per clutch, which are incubated for a month and a half. The chicks are brown and white, and remain in the nest for two months. They make begging “p-weeOO” calls, almost like the meowing of a cat, repeatedly for food. The male does most of the feeding of the children. The young remain with at least one of the two adults for another month after fledging, before going off on their own. They breed for the first time when they are two or three years old.

By Jorge Dantas, CC BY-SA 4.0

Ecosystem: Crane Hawks are found in all sorts of habitats, from dry deciduous forest to rainforest, from mangroves to savanna, from grassland to ponds and marshes. It is even found in human-created habitats such as plantations and farms. It is usually found at lower elevations.

Other: Crane Hawks are not considered threatened with extinction, even though they’re fairly uncommon. Different populations are more common than others, with the populations of Mexico going down a bit.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Bierregaard, R.O., Jr, Boesman, P., Marks, J.S. & Kirwan, G.M. (2019). Crane Hawk (Geranospiza caerulescens). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Jobling, J. A. 2010. The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. Christopher Helm Publishing, A&C Black Publishers Ltd, London.

#Geranospiza#Crane Hawk#Geranospiza caerulescens#Hawk#Dinosaur#Bird#Birds#Dinosaurs#Raptor#factfile#accipitrimorph#carnivore#Flying Friday#Quaternary#South America#North America#Birblr#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

216 notes

·

View notes

Text

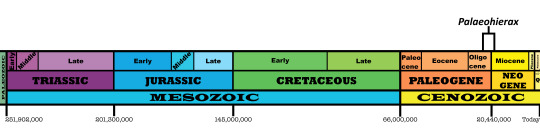

Palaeohierax gervaisii

By Scott Reid

Etymology: Old Hawk

First Described By: Milne-Edwards, 1863

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Inopinaves, Telluraves, Afroaves, Accipitrimorphae, Accipitriformes, Accipitridae

Status: Extinct

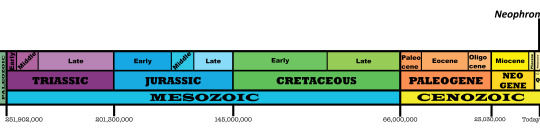

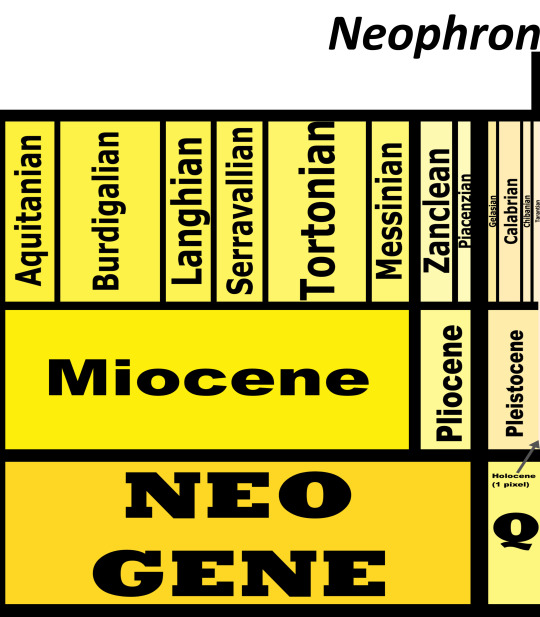

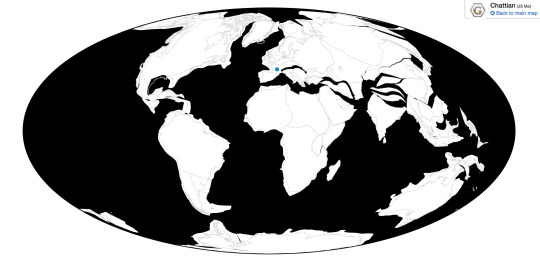

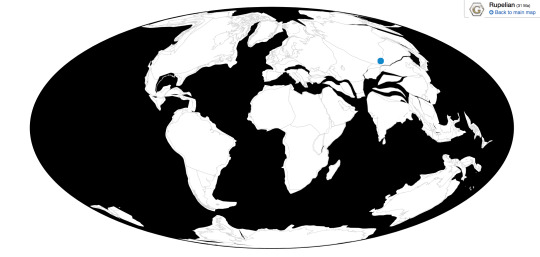

Time and Place: Sometime between 27 and 22 million years ago, from the Chattian of the Oligocene through the Aquitanian of the Miocene.

Palaeohierax is known from near Chaptuzat, in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes of France

Physical Description: Palaeohierax is one of many fossil birds known from mainly toe bones, but surprisingly, this toe bone is well preserved and tells us a decent amount about this dinosaur. This toe clearly marks Palaeohierax as a raptor, probably a daytime one; it is wider and flatter than those of hawks, and more robust than hawks as well, linking it in most likely to Ospreys or Eagles. It is also very similar to the living Palm-Nut Vulture, so it’s difficult to place it exactly within the Accipitrids. It has a less broad outer surface than Eagles, and does have a little bit of an enlarged barrel to the toe as in the Palm-Nut Vulture. However, it has small portions to the bone and strong edges, much like eagles. A part of a leg bone and hand bone have been found as well, but they are more fragmentary than the toe bone.

So, in short, Palaeohierax would have resembled a cross between hawks and the Palm-Nut Vulture - sort of a catch-all Accipitrid, but robust as well. This means it may have actually resembled the Bearded Vulture in appearance. It would have been about the same size as the modern White-Tailed Eagle, which has a typical wingspan of up to 2.45 meters - making Palaeohierax on the larger side for birds of prey.

Diet: As a large, robust bird of prey, Palaeohierax would have mainly fed upon other animals such as mammals, reptiles, and birds.

By José Carlos Corteés

Behavior: Palaeohierax would have probably resembled living birds of prey in its behavior, spending much of its day flying around and searching for prey; it would have dived down upon spotting them and used its large talons to grab onto its food (which would have been especially robust and muscular). It’s possible it would have also eaten carrion, given its similarities to some vultures; but it’s uncertain if that would have made up the bulk of its diet, especially given how its toes seem well adapted for hunting prey. As a dinosaur, it would have most likely taken care of its young, but more specifics on its breeding behavior are unknown.

Ecosystem: Palaeohierax probably lived alongside the shoreline of France at the time, given what sorts of other animals have been found in the same time and region. That being said, the exact fossil location of Palaeohierax has not been well reported. This was a fairly lush coastal environment, with a variety of pine trees, as well as many kinds of algae.

Here, there were many kinds of animals that Palaeohierax would have been able to feed upon - different turtles such as Ergilemys and Ptychogaster; lizards like Pseudeumeces, Dracaenosaurus, and Ophisauromimus; many kinds of rodents, shrews, a horse-like rhino relative called Allacerops, true rhinoceroses by the names of Molassitherium and Ronzotherium, and some early cats like Proailurus that would have probably attempted to hunt Palaeohierax in return. There was also a large, bulky hoofed mammal called Paenanthracotherium. As for other dinosaurs, they weren’t quite as commonly fossilized; but the gannet Empheresula was present in the same general time and place.

Other: Palaeohierax, despite its mysterious taxonomic placement within the birds of prey, is one of the few vulture-like dinosaurs known from the Neogene of Europe; and one of only a handful of Accipitrids from this time and place overall.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Augé, M. L. 2005. Evolution des lézards du Paléogène en Europe. Mémoires du Muséum national d'histoire naturelle 192:1-369

Boev, Z. 2010. Gyps bochenskii sp. N. (Aves: Falconiformes) from the Late Pliocene of Varshets (NW Bulgaria). Acta Zoologica Bulgarica 62 (2): 211 - 242.

Boev, Z. 2012. Circaetus rhodopensis sp. N. (Aves: Accipitriformes) from the Late Miocene of Hadzhidimovo (SW Bulgaria). Acta Zoologica Bulgarica 64 (1): 5 - 12.

Lambrecht, K. 1933. Handbuch der Palaeornithologie. 1-1024

Lydekker, R. 1891. Catalogue of the Fossil Birds in the British Museum (Natural History). British Museum (Natural History). 28.

Manegold, A., M. Pavia, P. Haarhoff. 2014. A new species of Aegypius vulture (Aegypiinae, Accipitridae) from the Early Pliocene of South Africa. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 34 (6): 1394 - 1407.

Mayr, G. 2009. Paleogene Fossil Birds. Springer Science & Buisness Media: 159.

Milkovsky, J. 2009. Evolution of the Cenozoic marine avifaunas of Europe. Annales Naturhistorisches Museum Wien 111(A):357-374

Milne-Edwards, A. 1869. Recherches anatomiques et paléontologiques pour servir à l'histoire des oiseaux fossiles de la France. G. Masson, France. 456 - 458.

Scherler, L., F. Lihoreau, and D. Becker. 2019. To split or not to split Anthracotherium? A phylogeny of Anthracotheriinae (Cetartiodactyla: Hippopotamoidea) and its palaeobiogeographical implications. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 185(2):487-510

#Palaeohierax#Palaeohierax gervaisii#Bird#Dinosaur#Raptor#Bird of Prey#accipitrimorph#Birds#Dinosaurs#Prehistoric Life#Birblr#Palaeoblr#Prehistory#Paleontology#Hawk#Eagle#Vulture#Paleogene#Neogene#Eurasia#Carnivore#Flying Friday#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature#factfile

146 notes

·

View notes

Text

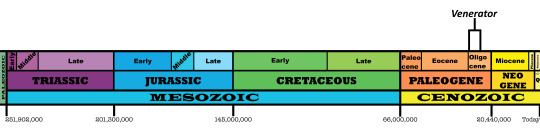

Venerator dementievi

By Scott Reid

Etymology: Hunter (but spelled badly)

First Described By: Kurochkin, 1968

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Passerea, Telluraves, Afroaves, Accipitrimorphae, Accipitriformes, Accipitridae

Status: Extinct

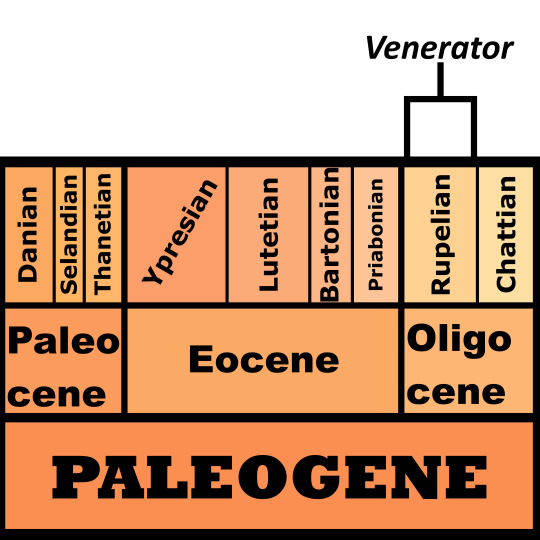

Time and Place: Sometime between 34 and 28 million years ago, in the Rupelian of the Oligocene of the Paleogene

Venerator is known from the Hsanda Gol Formation in Mongolia

Physical Description: It is a bit uncertain what Venerator was, but most signs point to it being a bird of prey, something like a buzzard. As such, it would have been a fairly large bird, with strong legs and a strong beak. Beyond that, it’s only known from part of the wing, which is sturdy - so it probably utilized flight extensively in its lifestyle, but that’s about all we can say.

Diet: If it was a bird of prey, Venerator probably ate mainly prey like mammals and other birds.

Behavior: It is uncertain how Venerator would have behaved, especially since it isn’t certain what it was, but it seems likely it would have behaved like modern birds of prey - flying around a lot, using good eyesight to find prey, and using its beak and talons to hack apart food. It probably would have taken care of its young, though it’s especially uncertain what its behavior would have been.

Ecosystem: Venerator lived in an early-Oligocene central Eurasian environment, featuring many iconic mammals of the time, even if Venerator itself was something of a mystery. This would have been a desert-scrub environment, very dry and open - allowing Venerator to see and catch prey rather quickly. There were many rodents, Leptictids, Hedgehogs, and rabbits that were good food for Venerator. There was only large browsing ungulate, Paraceratherium, which only migrated through the area; the wolf-sized predator Hyaenodon would have probably been a major threat against Venerator. There were also lizards for Venerator to hunt. There were also smaller predators, including cats, weasels, wolverines, primitive bears, and a false sabertooth cat called Nimravus, but they were all fairly small. Smaller hoofed mammals included gazelles and cows (naturally, none of these were living forms, but slightly weirder extinct kinds). As for other dinosaurs, the only known one was Heterostrix - an owl!

Other: Venerator was originally named Tutor dementievi, before being reassigned to the genus Venerator. Though Venerator means “worshipper”, it seems more likely that the original authors meant

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Brodkorb, P. (1964). Catalogue of fossil birds: Part 2 (Anseriformes through Galliformes). University of Florida.

Dashzeveg, D. 1985. Nouveaux Hyaenodontidae (Creondonta, Mammalia) du Paléogène de Mongolie. Annales de Paléontologie 71(4):223-256.

Farmer, D. 2012. Avian Biology, Volume VIII. Nature. 113.

Fossil Mammals from the Oligocene Hsanda Gol Formation, Mongolia: With Notes on the Paleobiology of Cricetops Dormitor. Insectivora, rodentia and deltatheridia, Part 1, James Silvan Mellett, 1966.

Mayr, G. 2009. Paleogene Fossil Birds. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg. 160.

Prothero, Donald R.. Life of the Past : Rhinoceros Giants: the Paleobiology of the Indricotheres, Indiana University Press, 2013. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Rothwell, Tom (2004). "New Felid Material from the Ulaan Tologoi Locality, Loh Formation (Early Miocene) of Mongolia". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History (Chapter 12). 285: 157–165.

#Venerator dementievi#Venerator#Bird#Dinosaur#Raptor#Bird of Prey#Birds#Dinosaurs#Accipitrimorph#Flying Friday#Paleogene#Eurasia#Carnivore#Birblr#Palaeoblr#Factfile#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hamirostra melanosternon

By Jarrod, CC BY 2.0

Etymology: Hook Bill

First Described By: Gould, 1841

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Inopinaves, Telluraves, Afroaves, Accipitrimorphae, Accipitriformes, Accipitridae, Milvinae

Status: Extant, Least Concern

Time and Place: Within the Last 10,000 years, in the Holocene of the Quaternary

The Black-Breasted Buzzard is known entirely from Australia

Physical Description: The Black-Breasted Buzzard is a very large bird, about 51 to 61 centimeters long, with a huge wingspan of up to 156 centimeters. The adults are mostly black, with orange spotting all over the wings and back; their necks are bright orange, and that orange extends to a small stripe above the eye. They have large, hooked bills, and long black tail feathers. Their legs have orange feathers, and their feet end in large talons. Juveniles are more pale in color, with some dark streaking on the breast feathers.

Diet: The Black-Breasted Buzzard mainly feeds on mammals, birds, reptiles, and carrion - especially rabbits, nestling birds, and large lizards.

By Benjamint444, CC BY-SA 3.0

Behavior: This bird will glide at a moderate height, soaring over the open habitats it frequents; it will then swoop to snatch prey from trees or seizing it on the ground. They’ll break eggs of large ground-nesting birds by hitting them with their bills, or hurling stones at them from their bills. This is a very quiet bird, even while courting; they do utter “yik-yik-yik” noises and whistles while interacting with family members, and breeding females make wheezing sounds to get their mates to mate with them.

The Black-Breasted Buzzard breeds throughout June through January, concentrating from September to December. They usually nest alone in eucalyptus groves, though they may be near other raptors. They are monogamous, staying in one breeding pair throughout their lives. They make nests out of a platform of sticks, lined with green leaves. Usually two eggs are laid and then incubated by the female for more than a month, while the male provides food. The chicks are very fluffy and white, and fledge after two months, but stay with their parents for two more months. They reach sexual maturity at 2 years of age. Some of these birds stay in one place throughout the year, while others will migrate - mainly due to drought.

By Lip Kee, CC BY-SA 2.0

Ecosystem: The Black-Breasted Buzzard lives entirely in semi-arid woodlands, savannas, plains, and deserts of Australia, usually at lower elevations and avoiding continuous forests.

Other: There are about 1,000 to 10,000 Black-Breasted Buzzards in the wild, and though they have had some sub-population decline, they don’t seem to be threatened with extinction. They are, however, sensitive to human activity, and negatively affected by decrease in prey mammal populations and illegal egg collecting.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Debus, S., Boesman, P. & Marks, J.S. (2019). Black-breasted Buzzard (Hamirostra melanosternon). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Jobling, J. A. 2010. The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. Christopher Helm Publishing, A&C Black Publishers Ltd, London.

#hamirostra#hamirostra melanosternon#Black-Breasted Buzzard#Buzzard#Dinosaur#Bird#Raptor#Birblr#Factfile#Carnivore#Australia and Oceania#Quaternary#Theropod Thursday#afroavian#accipitrimorph

75 notes

·

View notes

Text