#Act of Supremacy 1534

Text

⚜️ Field Armor of King Henry VIII of England, Italian, ca.1544

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

⠀

Today in History 📅

In 1534 English parliament passes the Act of Supremacy making Henry VIII and all subsequent monarchs the Head of the Church of England

⠀

10 facts about Henry VIII:

1. Henry VIII (1491–1547) is one of the most written about kings in English history. He established the Church of England.

2. In his youth, he was one of the Catholic Church’s staunchest supporters.

3. He is credited with establishing the Royal Navy, encouraging shipbuilding and the creation of anchorages and dockyards.

4. Not only could Henry speak Latin, French, Ancient Greek and Spanish, but also played the lute and organ, sang, played tennis and jousted.

5. Henry VIII was a merciless king.

He sent more men and women to their deaths than any other English monarch. In fact, it's estimated 57,000 - 72,000 people were executed during his 37-year reign.

6. He is the only English monarch to have ruled Belgium.

Henry captured the city of Tournai in 1513 and went on to rule it for six years. However, the city was returned to France in 1519 following the Treaty of London.⠀

7. He was paranoid about illness, terrified he would die before he had an heir.

8. He had six wives in total.

They were Catherine of Aragon, Anne Boleyn, Jane Seymour, Anne of Cleves, Catherine Howard and Catherine Parr.

9. He died in debt. Henry was a big spender. By his death on 28 January 1547, he had accumulated 50 royal palaces and spent vast sums on his collections and gambling. Not to mention the millions he pumped into wars with Scotland and France. When Henry’s son, Edward VI, took the throne, the royal coffers were in a sorry state.

10. Henry VIII was the first English king to be called 'Your Majesty.'

⠀

- -

⚜️ Полевые доспехи короля Англии Генриха VIII, Италия, ок. 1544

⠀

Этот день в истории 📅

В 1534 году Английский парламент принимает Акт о верховенстве, в соответствии с которым Генрих VIII и все последующие монархи становятся главой Англиканской церкви

⠀

10 фактов о Генрихе VIII:

1. Генрих VIII (1491–1547) — один из самых популярных королей в английской истории. Он основал англиканскую церковь.

2. В юности он был ярым сторонником католической церкви.

3. Ему приписывают создание Королевского морского флота, развитие судостроения и создание якорных стоянок и верфей.

4. Генрих не только мог говорить на латыни, французском, древнегреческом и испанском языках, но также играл на лютне и органе, пел, играл в теннис и участвовал в рыцарских турнирах.

5. Он был беспощадным королем.

По разным оценкам, за время его 37-летнего правления было казнено от 57000 до 72000 человек.

6. Он единственный английский монарх, правивший Бельгией.

Генрих захватил город Турне в 1513 г. и правил им в течение шести лет. Однако в 1519 г. город был возвращен Франции по Лондонскому договору.

7. Он был параноиком в отношении болезней и боялся, что умрет, не успев обзавестись наследником.

8. У него было 6 жен. Это были Екатерина Арагонская, Анна Болейн, Джейн Сеймур, Анна Клевская, Екатерина Говард и Екатерина Парр.

9. Он умер в долгах.

Генрих был большим транжирой. К моменту своей смерти 28 января 1547 г. он успел построить 50 королевских дворцов, потратить огромные суммы на свои коллекции и азартные игры. Не говоря уже о миллионах, которые он влил в войны с Шотландией и Францией. Когда сын Генриха, Эдуард VI, вступил на престол, королевская казна находилась в плачевном состоянии.

10. Генрих VIII был первым английским королем, которого называли Your Majesty («Ваше Величество») вместо Your Grace («Ваша милость»).

⠀

#ArmsandArmour #история #доспехи #средневековье #armour #medievalarmour #armsandarmor #history #ГенрихVIII #HenryVIII

#medieval#средневековье#middleages#history#armor#armours#история#harnisch#armadura#armour#henryviii#генрих viii

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

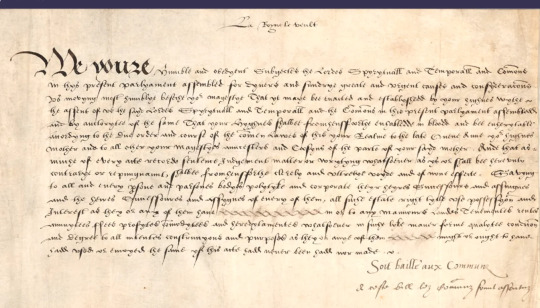

An Act whereby the Queen's Highness Elizabeth is restored in Blood to the late Queen Anne Boleyn, her Highness's Mother, 1558

In her first parliament on the 5th of December, 1558, Queen Elizabeth I restored The Act of Supremacy declaring her as Supreme Governor of the Church of England which brought some doubts into the spotlight, especially regarding her rights to the throne.

Now, the matter of her legitimacy was and always remained unclarified since her mother, Anne Boleyn, was found guilty and executed. The Church of England and an act of Parliament declared her marriage to Henry VIII null and void in 1536 the night before her execution, so she died a marchioness [of Pembroke]. Henry VIII, all his life after May 1536, declared his marriage to Anne was invalid, and when Queen Kateryn Parr convinced Henry to add Mary and Elizabeth to the succession it was with the condition that they marry someone vetoed by the majority of Prince Edward's appointed Privy Council, and as we know, after Edward died and the Earl of Northumberland's rebellion was put down Queen Mary rose to the throne and the conditions of said will was unattainable (referring as to the support of the majority of the PC), all that was left was a clear line of succession:

"As to the succession of the Crown, it shall go to Prince Edward and the heirs of his body. In default, to Henry's children by his present wife, Queen Catharine, or any future wife. In default, to his daughter Mary and the heirs of her body, upon condition that she shall not marry without the written and sealed consent of a majority of the surviving members of the Privy Council appointed by him to his son Prince Edward. In default, to his daughter Elizabeth upon like condition. In default, to the heirs of the body of Lady Frances, eldest daughter of his late sister the French Queen. In default, to those of Lady Elyanore, second daughter of the said French Queen. And in default, to his right heirs. Either Mary or Elizabeth, failing to observe the conditions aforesaid, shall forfeit all right to the succession."

-https://www.tudorsociety.com/30-december-1546-henry-viiis-will/

So, after attaining her crown through the strength of arms and said will, Queen Mary undid the Act of Supremacy of 1534, brought back the powers of Rome, and with their support made the marriage of her father and Katharine of Aragon legal and the Church of England heretical, thus Elizabeth was doubly the bastard.

After Queen Mary's death and Queen Elizabeth's accession, following the order of the will, the binds with Rome were severed this time and the laws and acts passed by Queen Mary regarding this were repelled, thus leaving Katharine of Aragon again with the title of Dowager Princess of Wales (as to her marriage to Prince Arthur, Henry VIII's older brother) and the Church of England reinstated, which came with the mere fact that twenty-one years ago it declared the marriage of her parents null and void. But she couldn't simply overturn a decision made by the King, her sire which gave her the claim to the throne without undermining the power of kings, and there was also the fact that her mother was a convicted felon for which by the relation of blood in the English law of yore made one unfit to receive high titles, but of course, the majority of people, protestants and such, wanted her and thought her fit.

So Queen Elizabeth can't openly make the marriage of her parents legal without undermining the CoE nor make the charges against her mother be posthumously dropped without undermining her new office and late father, but what she can do is make herself the daughter of a true Queen of England which had her name marred unjustly, she can't change the law and edicts but she can change the people's perception of who is right, so thus:

"Elizabeth I reinstated her mother Anne Boleyn as a Queen, as Anne had been stripped of her titles during her trial. This would have reinforced Elizabeth's right to the throne and perhaps been important to the new queen privately"

-https://ukparliament.shorthandstories.com/succession/

As the head of the protestants in the nation, the idea that she was the daughter of a martyr of religious freedom was spread and made her a beacon of hope, the way people viewed Queen Anne back then would have been of a woman wronged who's favor and righteousness God showed by the daughter that would save them from the inquisition. Excellent PR if you ask me.

Parliamentary Archives, an edict that restores the title of Queen to Anne Boleyn (if anyone can read and make a transcript it would be amazing) HL/PO/PU/1/1558/1Eliz1n21

#history#anne boleyn#elizabeth i#elizabeth tudor#england#mary i#katherine of aragon#henry viii#tudor dynasty#tudor period#tudor history#catherine parr#accession#parliament#church of england#edward vi

52 notes

·

View notes

Photo

One of the most revolutionary events in English history, the Dissolution of the Monasteries (sometimes referred to as the Suppression of the Monasteries), was the set of administrative and legal processes between 1536 and 1541, by which King Henry VIII disbanded monasteries, priories, convents and friaries in England, Wales and Ireland; in effect, sacking and looting them for their income, land and assets.

In order to grasp the impact of the Dissolution, it is necessary to understand that in the late 1530s there were nearly 900 religious houses in England (around 260 for monks, 300 for regular canons, 142 nunneries and 183 friaries). As such, some 12,000 people in total (4,000 monks, 3,000 canons, 3,000 friars and 2,000 nuns), were engaged in carrying out the functions of those religious houses. To put this in context: if the adult male population was 500,000, one adult man in fifty was in religious orders.

Henry was given authority by the Act of Supremacy, passed by Parliament in 1534, which made him Supreme Head of the Church in England, thus separating England from Papal authority; the King's position further strengthened by two Acts of Suppression (1536, and 1539). The policy was originally envisaged as increasing the regular income of the Crown, and much former monastic property was sold off in the 1540s to fund Henry's military campaigns; though by the time Henry VIII turned his mind to the business of monastic reform, royal action to suppress religious houses already had a history of more than 200 years.

The first case was that of the so-called, Alien Priories (some, merely agricultural estates with a single foreign monk in residence; others, rich foundations in their own right, such as Lewes Priory, which not only answered to Cluny of Paris, but sent money overseas, too).

Given the fairly constant state of war between England and France in the Late Middle Ages, the money sent to France by these Alien Houses was a matter of significant grievance in England. As such, the first sequestrations of the assets of the Alien Priories began under King Edward I, continued in the reign of Edward III, and still further continued by act of Parliament in 1414, under the authority of Henry V.

Money and land acquired by the Suppression greatly increased the royal purse, though some of it was also used to found educational foundations: most often setting up new colleges at both Oxford University and Cambridge University. Further instances, include: John Alcock (Bishop of Ely), acquiring the Benedictine nunnery of Saint Radegund to found Jesus College, Cambridge (1496), and William Waynflete (Bishop of Winchester), acquiring Selborne Priory in 1484 for Magdalen College, Oxford.

Dissolution of Monasteries was not an act exclusive to England. In 1521, Martin Luther published 'De votis monasticis' (On the monastic vows), a treatise declaring monastic life was not compatible with the true spirit of Christianity. In Sweden in 1527, King Gustavus Vasa secured an edict allowing him to confiscate any monastic lands he deemed necessary to increase royal revenues; and in Denmark in 1528, King Frederick I grabbed 15 of the houses of the wealthiest monasteries and convents.

King Henry VIII's chief political and legal architect in the Dissolutions was Thomas Cromwell (also instrumental in monastic suppressions instigated by Cardinal Wolsey); though Henry is also said to have been influenced by Desiderius Erasmus and Thomas More; both of whom ridiculed such monastic practices as repetitive formal religion and superstitious pilgrimages for the veneration of relics.

Most parish churches had been endowed with Chantries (each maintaining a priest to say mass for the souls of their donors), and these continued until they too were dissolved under the Chantries Act (of 1547), by Henry VIII's son, Edward VI.

Along with the destruction of the monasteries, the related destruction of the monastic libraries is said to have been on a catastrophic scale: Worcester Priory, for example (now Worcester Cathedral), had 600 books at the time of the dissolution; only six of them are known to have survived intact to the present day.

Similarly, the Abbey of the Augustinian Friars at York, had a library of 646 volumes, of which only three are known to have survived.

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

ok, so i misremembered this article somewhat...fitzroy had provincial appearances throughout both his stepmothers' (i guess coa was technically his stepmother by proxy of sorts, altho the title doesn't fit as well with the connotation of that word as it does when your father (re)marries someone in your lifetime, rather than before) reigns, but 1533 was the last year of players and minstrels performing:

"In records to date, appearances by Fitzroy’s entertainers cease in 1534, less than a year after the birth of Henry’s legitimate (for a time) Princess Elizabeth [...]"

Advertising Status and Legitimacy: or, Why Did Henry VIII’s Queens and Children Patronize Travelling Performers?, James H. Forse

...thereafter it was only bearward performances. princess mary's, predictably, also ended by 1533, altho that might be more instructive of how they both reacted to their new stepmother and the religious supremacy (understandably...fitzroy only had to accept a continuation of status quo re his status, and mary was expected to accept a reversal, rather unrealistically, by her father).

princess elizabeth did not have troupes of entertainers (altho i wonder in counterfactual if she would have, perhaps by the age of six or seven, which is when princess mary began to have them) perform in her name (altho personally, i wonder if anne's players mentioned her in their acts), and the provincial performances in prince edward's name eclipse mary's and demonstrate how the importance of the legitimacy of princes tended to supersede that of princesses, these performances began basically right when he was born (whereas mary's did not start until 1525), and there were over seventy such performances, whereas mary had around twenty-five in her name, as princess.

"The scanty information we possess about the personnel of these other royal troupes suggests King Henry gave his support and prestige to his wives’ and children’s entertainment troupes. John Slye moved from Henry’s personal troupe to Princess Mary’s, to Anne Boleyn’s, to Jane Seymour’s; his brother William Slye moved

from Henry’s troupe to Mary’s, to Anne Boleyn’s. John Young moved from Henry’s troupe to Jane Seymour’s, and then to Prince Edward’s troupe."

Advertising Status and Legitimacy: or, Why Did Henry VIII’s Queens and Children Patronize Travelling Performers?, James H. Forse

comparably, there is also a chart of elizabeth woodville's provincial appearances ... predictably, a gap between 1464 and 1467, another betwen 1470 (coinciding with the birth of prince edward/edward v, also the gap attributed to when she took sanctuary) and 1473, her last being in 1482 (as edward iv died and richard iii took the throne in 1483).

edward plantagent's last was 1482, which makes sense, as richard iii wouldn't have wanted to promote him as heir above his own son...richard iii's son had a provincial performance in his name, indeed, in 1483, before his death.

arthur tudor had a comparable amount of performances in his name as compared to the future edward vi, as heir. henry, duke of york, however, was not forgotten, he had performances in his name, too, starting with the year he was invested as duke of york, with a brief pause from 1500-02 (the focus, doubtless, turning to arthur and his upcoming marriage alliance), picking up again in 1502 upon arthur's death, continuing until he succeeded the throne in 1509.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

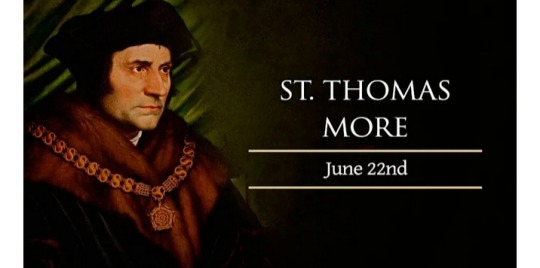

SAINT OF THE DAY (June 22)

On June 22, the Catholic Church honors the life and martyrdom of St. Thomas More, the lawyer, author and statesman who lost his life opposing King Henry VIII's plan to subordinate the Church to the English monarchy.

Thomas More was born on 7 February 1478, son of the lawyer and judge John More and his wife Agnes.

He received a classical education from the age of six.

At age 13, he became the protege of Archbishop John Morton, who also served an important civic role as the Lord Chancellor.

Although Thomas never joined the clergy, he would eventually come to assume the position of Lord Chancellor himself.

More received a well-rounded college education at Oxford, becoming a “renaissance man” who knew several ancient and modern languages. He was also well-versed in mathematics, music and literature.

His father, however, determined that Thomas should become a lawyer, so he withdrew his son from Oxford after two years to focus him on that career.

Despite his legal and political orientation, Thomas was confused in regard to his vocation as a young man.

He seriously considered joining either the Carthusian monastic order or the Franciscans.

He followed a number of ascetic and spiritual practices throughout his life – such as fasting, corporal mortification, and a regular rule of prayer – as means of growing in holiness.

In 1504, however, More was elected to Parliament.

He gave up his monastic ambitions, though not his disciplined spiritual life, and married Jane Colt of Essex.

They were happily married for several years and had four children together, though Jane tragically died in childbirth in 1511.

Shortly after her death, More married a widow named Alice Middleton, who proved to be a devoted wife and mother.

Two years earlier, in 1509, King Henry VIII had acceded to the throne.

For years, the king showed fondness for Thomas, working to further his career as a public servant.

He became a part of the king's inner circle, eventually overseeing the English court system as Lord Chancellor.

More even authored a book published in Henry's name, defending Catholic doctrine against Martin Luther.

More's eventual martyrdom would come as a consequence of Henry VIII's own tragic downfall.

The king wanted an annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, a marriage that Pope Clement VII declared to be valid and indissoluble.

By 1532, More had resigned as Lord Chancellor, refusing to support the king's efforts to defy the Pope and control the Church.

In 1534, Henry VIII declared that every subject of the British crown would have to swear an oath affirming the validity of his new marriage to Anne Boleyn.

Refusal of these demands would be regarded as treason against the state.

In April of that year, a royal commission summoned Thomas to force him to take the oath affirming the King's new marriage as valid.

While accepting certain portions of the act which pertained to Henry's royal line of succession, he could not accept the king's defiance of papal authority on the marriage question.

More was taken from his wife and children, and imprisoned in the Tower of London.

For 15 months, More's wife and several friends tried to convince him to take the oath and save his life, but he refused.

In 1535, while More was imprisoned, an act of Parliament came into effect declaring Henry VIII to be “the only supreme head on earth of the Church in England,” once again under penalty of treason.

Members of the clergy who would not take the oath began to be executed.

In June 1535, More was finally indicted and formally tried for the crime of treason in Westminster Hall.

He was charged with opposing the king's “Act of Supremacy” in private conversations, which he insisted had never occurred.

But after his defense failed, and he was sentenced to death, he finally spoke out in open opposition to what he had previously opposed through silence and refusal.

More explained that Henry's Act of Supremacy was contrary “to the laws of God and his holy Church.”

He explained that “no temporal prince” could take away the prerogatives that belonged to St. Peter and his successors according to the words of Christ.

When he was told that most of the English bishops had accepted the king's order, More replied that the saints in heaven did not accept it.

On 6 July 1535, the 57-year-old More came before the executioner to be beheaded.

“I die the king's good servant,” he told the onlookers, “but God's first.”

His head was displayed on London Bridge but later returned to his daughter Margaret who preserved it as a holy relic of her father.

Thomas More was beatified by Pope Leo XIII on 29 December 1886. He was canonized by Pope Piux XI on 19 May 1935.

The Academy Award-winning film “A Man For All Seasons” portrayed the events that led to his martyrdom.

A Man for All Seasons (1966 film)

A Man for All Seasons (1988 television film)

#Saint of the Day#St. Thomas More#King Henry VIII#A Man for All Seasons (1966)#A Man for All Seasons (1988)#Pope Clement VII

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

In 1534, an Act of Succession stated the lawfulness of Henry's marriage to Anne Boleyn and that their children would be true heirs to the throne, and all English male subjects (by which all subjects were supposed to be covered) were required to swear an oath agreeing this.

The oath read that they would be true to Queen Anne and believe and take her for the lawful wife of the king and rightful queen of England, and utterly to think the Lady Mary, daughter to the king by Queen Catherine, but as a bastard, and thus to do without any scrupulosity of conscience. Henry wanted the whole kingdom to be complicit in his decision, even in their thoughts. Everyone was forced to agree to the king's divorce, and according to the oath's preamble, to his position as Supreme Head of the Church, in place of the Pope.

Thomas More, alone among the laity, John Fisher, alone among the bishops, along with three Carthusian monks, refused to swear. All were sent to the Tower, and the hastily passed Act of Treasons, also from 1534, made it treason to call the king a heretic, a tyrant, an infidel, or a schismatic. I always think there's something slightly ironic there—something slightly tyrannous, one might say—in making it illegal for someone to call you a tyrant. It was also treason to imagine the death of the king in words, or, quote, "maliciously to deny the Royal Supremacy."

— Explainer: Henry VIII's Break with Rome

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The Buggery Act 1533, formally An Acte for the punishment of the vice of Buggerie, was an Act of the Parliament of England that was passed during the reign of Henry VIII. It was the country’s first civil sodomy law, such offenses having previously been dealt with by the ecclesiastical courts. The term buggery, not defined in the text of the legislation, was later interpreted by the courts to include only anal penetration and bestiality, regardless of the sex of the participants, but not oral penetration.”

“The Act was piloted through Parliament by Henry VIII’s minister Thomas Cromwell (though it is unrecorded who actually wrote the bill), and punished “the detestable and abominable Vice of Buggery committed with Mankind or Beast.” Prior to the 1550s, the term “Buggery” was not used in a homosexual sense, rather related to any sexual act not related to procreation, regardless of the gender or species involved in the sexual act, and also covered sexual crimes of a non-consensual nature.”

“Henry may have intended it as a simple expression of political power along with other contemporary acts such as Submission of the Clergy Act 1533 and one year before the Act of Supremacy 1534. However, Henry later used the law thanks to execute monks and nuns (thanks to information his spies had gathered) and take their monastery lands”

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Events 11.3 (before 1960)

361 – Emperor Constantius II dies of a fever at Mopsuestia in Cilicia; on his deathbed he is baptised and declares his cousin Julian rightful successor.

1333 – The River Arno floods causing massive damage in Florence as recorded by the Florentine chronicler Giovanni Villani.

1468 – Liège is sacked by Charles I of Burgundy's troops.

1492 – Peace of Etaples between Henry VII of England and Charles VIII of France.

1493 – Christopher Columbus first sights the island of Dominica in the Caribbean Sea.

1534 – English Parliament passes the first Act of Supremacy, making King Henry VIII head of the Anglican Church, supplanting the pope and the Roman Catholic Church.

1783 – The American Continental Army is disbanded.

1793 – French playwright, journalist and feminist Olympe de Gouges is guillotined.

1812 – Napoleon's armies are defeated at the Battle of Vyazma.

1817 – The Bank of Montreal, Canada's oldest chartered bank, opens in Montreal.

1838 – The Times of India, the world's largest circulated English language daily broadsheet newspaper is founded as The Bombay Times and Journal of Commerce.

1848 – A greatly revised Dutch constitution, which transfers much authority from the king to his parliament and ministers, is proclaimed.

1867 – Giuseppe Garibaldi and his followers are defeated in the Battle of Mentana and fail to end the Pope's Temporal power in Rome (it would be achieved three years later).

1868 – John Willis Menard (R-LA) was the first African American elected to the United States Congress. Because of an electoral challenge, he was never seated.

1881 – The Mapuche uprising of 1881 begins in Chile.

1898 – France withdraws its troops from Fashoda (now in Sudan), ending the Fashoda Incident.

1903 – With the encouragement of the United States, Panama separates from Colombia.

1908 – William Howard Taft is elected the 27th President of the United States.

1911 – Chevrolet officially enters the automobile market in competition with the Ford Model T.

1918 – The German Revolution of 1918–19 begins when 40,000 sailors take over the port in Kiel.

1920 – Russian Civil War: The Russian Army retreats to Crimea, after a successful offensive by the Red Army and Revolutionary Insurgent Army of Ukraine.

1929 – The Gwangju Student Independence Movement occurred.

1930 – Getúlio Vargas becomes Head of the Provisional Government in Brazil after a bloodless coup on October 24.

1932 – Panagis Tsaldaris becomes the 142nd Prime Minister of Greece.

1935 – George II of Greece regains his throne through a popular, though possibly fixed, plebiscite.

1936 – Franklin D. Roosevelt is elected the 32nd President of the United States.

1942 – World War II: The Koli Point action begins during the Guadalcanal Campaign and ends on November 12.

1943 – World War II: Five hundred aircraft of the U.S. 8th Air Force devastate Wilhelmshaven harbor in Germany.

1944 – World War II: Two supreme commanders of the Slovak National Uprising, Generals Ján Golian and Rudolf Viest, are captured, tortured and later executed by German forces.

1946 – The Constitution of Japan is adopted through Emperor's assent.

1949 – Chinese Civil War: The Battle of Dengbu Island occurs.

1950 – Air India Flight 245 crashes into Mont Blanc, while on approach to Geneva Airport, killing all 48 people on board.

1956 – Suez Crisis: The Khan Yunis killings by the Israel Defense Forces in Egyptian-controlled Gaza result in the deaths of 275 Palestinians.

1956 – Hungarian Revolution: A new Hungarian government is formed, in which many members of banned non-Communist parties participate. János Kádár and Ferenc Münnich form a counter-government in Moscow as Soviet troops prepare for the final assault.

1957 – Sputnik program: The Soviet Union launches Sputnik 2. On board is the first animal to enter orbit, a dog named Laika.

0 notes

Text

The History and Beliefs of Anglicanism: A Comprehensive Overview

Anglicanism is the religious belief of the Church of England, and its affiliated churches in the US, British territories, and elsewhere. It includes those who accept the teachings of the English Reformation, as seen in the Church of England and similar offshoots. Anglicanism is primarily found in areas formerly under British control.

Beliefs

To understand Anglicanism as a religious system, let's look at the Established Church of England, keeping in mind that other parts of the Anglican communion may have differences in liturgy and church-government.

Members of the Church of England are Christians who have been baptized and claim to be members of the Church of Christ.

They accept the Authorized Version of the Scriptures as the Word of God.

They believe that the Scriptures are the sole and supreme rule of faith, containing everything necessary for salvation.

They use the Book of Common Prayer as the practical rule of their belief and worship, and hold to the three Creeds as standards of doctrine.

They believe in two sacraments of the Gospel – Baptism and the Lord's Supper – as generally necessary to salvation.

They claim to have Apostolic succession and a validly ordained ministry, and only permit those who are believed to be thus ordained to minister in their churches.

They believe that the Church of England is a true and reformed part or branch of the Catholic Church of Christ.

They maintain that the Church of England is free from all foreign jurisdiction.

They recognize the King as the Supreme Governor of the Church and acknowledge that to him "appertains the government of all estates whether civil or ecclesiastical, in all causes."

The clergy, before being appointed to a benefice or licensed to preach, subscribe to the Thirty-nine Articles, the Book of Common Prayer, and the doctrine of the Church of England as set forth therein, as agreeable to the Word of God.

The Bible can be interpreted in different ways. The Prayer Book's Eucharistic teaching can be interpreted differently. Some think apostolic succession is important, but not essential. Only the Apostles' Creed is required for the laity, and the Articles of Religion are binding only on the licensed and beneficed clergy.

Government

The Church of England's constitution was largely shaped by events during its settlement under the Tudors, within these vague outlines.

Original loyalty to Rome

Before Henry VIII split from Rome, the English Church was part of the Catholic Church under the Pope's jurisdiction. It did not exist as a separate religious system. The name Ecclesia Anglicana was used in the Catholic and Papal sense to represent the region of the one Catholic Church located in England and did not suggest any independence from Rome.

Pope Honorius III, in 1218, in his Bull to King Alexander speaks of the Scottish Church (Ecclesia Scotticana) as "being immediately subject to the Apostolic See."

The abbots and priors of England in their letter to Innocent IV, in 1246, declared that the English Church (Ecclesia Anglicana) is "a special member of the Most Holy Church of Rome."

In 1413 Archbishop Arundel, with the assent of Convocation, affirmed against the Lollards the faith of the English Church in a number of test articles, including the Divine institution of the Papacy and the duty of all Christians to render obedience to it.

In 1521, only thirteen years before the split, John Clerk, the English Ambassador at Rome, was able to assure the Pope in full consistory that England was second to no country in Christendom, "not even to Rome itself", in the "service of God and of the Christian Faith, and in the obedience due to the Most Holy Roman Church."

After the Act of Royal Supremacy (1534)

The first point of separation was due to Erastianism. When the news of the papal decision against divorce reached England, Henry VIII assented to four anti-papal statutes and in November, the statute of the Royal Supremacy declared the King to be Supreme Head of the English Church. The actual ministry of preaching and sacraments was left to the clergy, but all the powers of ecclesiastical jurisdiction were claimed by the sovereign. The chief note of Henrician settlement is the fact that Anglicanism was founded in the acceptance of the Royal, and the rejection of the Papal Supremacy, and was placed upon a decidedly Erastian basis.

When the Act of Royal Supremacy, which had been repealed by Queen Mary, was revived by Elizabeth, it suffered a modification in the sense that the Sovereign was styled "Supreme Governor" instead of "Supreme Head". Elizabeth reasserted the claim made by Henry VIII as to the Authority of the Crown in matters ecclesiastical, and the great religious changes made after her accession were carried out and enforced in a royal visitation commissioned by the royal authority.

In 1628, Charles I declared that it was his duty as king to maintain the Church and promote religious unity and peace. He ordered that differences in the Church's external policy be resolved in Convocation, but their decisions had to be approved by the Crown as long as they did not contradict the laws of the land.

In 1640, Archbishop Laud had canons drawn up in Convocation and published them. However, Parliament was outraged and he withdrew them. The House of Commons unanimously passed a resolution stating that the Clergy in Convocation had no power to create canons or constitutions in matters of doctrine, discipline, or to bind the Clergy and laity of the land without the common consent in Parliament. (Resolution, 16 December, 1640).

The effect of Royal Supremacy

The legislation under Henry VIII was revived by Elizabeth and confirmed in subsequent reigns. As a result, the Crown now has the jurisdiction that was previously held by the Pope before the Reformation. This was highlighted in Lord Campbell's Gorham judgment in April 1850.

Until 1833, the Court of Delegates, a special body appointed by the Crown, exercised supreme jurisdiction. It consisted of lay judges, sometimes with bishops or clergymen. After it was abolished, the King in Council took over its powers. Today, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council advises the King on matters previously handled by the Court. Its decisions, per the statute (2 and 3 William IV, xcii), are final and not subject to review.

This tribunal does not decide on articles of faith or the orthodoxy or heterodoxy of opinions. Its duty is limited to considering the doctrine of the Church of England as established by law and interpreting its Articles and formularies. In 1850, the Crown decided that Mr. Gorham's views on baptismal regeneration were not contrary to the established doctrine of the Church of England, despite protests and appeals from high Churchmen. Similarly, in 1849, when there was vehement opposition to the appointment of Dr. Hampden to the See of Hereford, the Prime Minister insisted on the right of the Crown to nominate, and the Court of Queen's Bench upheld his ruling.

The Anglican Church's spiritual authority has been a topic of debate among its divines. However, the Crown, backed by Parliament and the Law Courts, has practical control over the church's doctrines and those who teach them. After breaking away from Rome, the Crown took over the far-reaching regulative jurisdiction exercised by the Holy See. This authority was never effectively entrusted to the Anglican Spirituality, and there is still no living Church Spiritual Authority in the Anglican Church today. This has been a constant source of weakness, humiliation, and disorder.

In 1904, a commission investigated complaints about ecclesiastical discipline. It issued its report in July 1906, pointing out that laws of public worship have not been uniformly observed in the past. The commission recommended forming a Court that would accept the episcopate on questions of doctrine or ritual, while exercising the Royal Jurisdiction. This would be the first step towards emancipating the Spirituality from the civil power, to which it has been held for over three centuries.

Anglicanism is separate from the doctrine of Royal Supremacy, which is a result of its connection to the State and the circumstances of the English Reformation. Anglican Churches exist outside of England and Wales, where they are said to prosper without state ties. However, even in these countries, the Episcopate does not hold the decisive voice in the Anglican Church. Lay power in synods has shown that it can be a real master. The Anglican system still lacks the supremacy of Spirituality in the domain of doctrine, which is the sole guarantee of true religious liberty. The problem of supplying it remains unsolved, if not insoluble.

Doctrinal and liturgical formularies

The Anglican Church's doctrinal position can only be understood by studying its history. This history can be divided into several periods, including the Henrician period, which established an independent national church and transferred Church authority from the Papacy to the Crown. The Edwardian and Elizabethan periods further separated the Church from Rome and made doctrinal and liturgical changes that defined the Anglican Reformation and placed the nation within the Protestant movement of the sixteenth century.

First period: Henry VIII (1534-1547)

Although Henry VIII's policy after breaking with Rome appeared conservative, aiming to maintain a Catholic Church in England without the Pope, his actions contradicted his professions and were ultimately fatal.

Influence of English Protestant Sympathizers

By raising and maintaining three influential figures, Thomas Cromwell, Thomas Cranmer, and Edward Seymour, all of whom sympathized with the Reformation, Henry VIII paved the way for the rise of Protestantism under Edward and Elizabeth, whether intentionally or as a result of his indifference in his later years.

Henry negotiated with German Reformers in 1535, and in 1537, Cromwell and Cranner negotiated with Protestant princes in Smalkald. Three German divines were sent to London in 1538 to hold conferences with Anglican bishops and clergy. Thirteen articles based on the Lutheran Confession of Augsburg were agreed upon doctrinally, but the King refused to give way on the "Abuses." Although the negotiations formally ended, the Thirteen Articles were kept and eventually formed the nucleus of the Articles of Religion authorized under Edward VI and Elizabeth, showing almost verbal correspondence with the Lutheran Confession of Augsburg.

Second period: Edward VI (1547-1553)

After the death of Henry VIII in 1547, the reformation movement gained momentum under King Edward VI, a Protestant, and with the support of powerful figures like Seymour and Cranmer. During the five-year reign (1547-53), the Reformation party had full national power and introduced significant changes to doctrine and liturgy.

The Reformation brought a cardinal principle of denying the Sacrifice of the Mass. Cranmer upheld this and introduced a new English Communion Service under Edward VI. The Book of Common Prayer, authored by Cranmer, replaced the Latin Mass and was approved by Parliament in 1549. Another Prayer Book was drawn up by the reformers, omitting any mention of Altar or Sacrifice and was authorized by Parliament in 1552. An Order in Council issued to Bishop Ridley required the altars to be torn down, and movable tables substituted in 1551.

A lot of Catholic practices and sacramentals were stopped by Royal Proclamations and episcopal visitations. These practices include lights, incense, holy water, and palms. Cranmer and his followers mainly initiated and quickly carried out these reforms, which reflected their beliefs.

In 1553, a royal decree required bishops and clergy to subscribe to 42 Articles of Religion. These articles incorporated much of what was in the Thirteen Articles agreed upon with the Germans. The article on the Eucharist was changed to align with the teachings of the Swiss reformer, Bullinger.

Third period: Elizabeth I (1558-1603)

In November 1558, Queen Elizabeth replaced Queen Mary and resumed the work of Henry VIII and Edward VI.

The new settlement of religion was based on the more Protestant Prayer Book of 1552, with a few modifications. This version remains substantially unchanged today. The statement that Pius IV offered to approve the Prayer Book has no historical foundation. No contemporary evidence supports it. Camden, the earliest Anglican historian who mentions it, says: "I never could find it in any writing, and I do not believe any writing of it to exist. To gossip with the mop is unworthy of any historian" (History, 59). Fuller describes it as the mere conjecture "of those who love to feign what they cannot find".

The 39 Articles

In 1563, the Edwardian Articles were revised under Archbishop Parker. The number was reduced to 38 and some were added, altered, or dropped. The Articles were ratified by the Queen, and the bishops and clergy were required to assent and subscribe to them. In 1571, the XXIXth Article was inserted, despite the opposition of Bishop Guest, stating that the wicked do not eat the Body of Christ.

During Elizabeth's reign, Anglican teaching and literature leaned towards Calvinism and Puritanism. In 1662, the Prayer Book, which had been suppressed during the Commonwealth, was revised in Convocation and Parliament to emphasize the Episcopal character of Anglicanism against Presbyterianism. The amendments made were numerous, but those of doctrinal significance were few. The most notable were the reinsertion of the Black Rubric and the introduction in the form of the words, "for the office of a Bishop" and "for the office of a Priest", in the Service of Ordination.

Anglican Formularies

The historical and doctrinal significance of the Anglican formularies can only be determined by a thorough examination of the evidence.

1st, study the plain meaning of the text.

2nd, by studying the historical context and circumstances of their framing and authorization;

3rd, by the established beliefs of their main authors and followers.

4th, compared to pre-Reformation Catholic formularies that they replaced.

5th, to understand their teachings better, we need to study their sources and the specific words they used during the controversies of the time.

6th, to avoid narrow-mindedness in examining the English Reformation, one must study the broader Reformation movement in Europe, of which it was a part and result.

Here it is only possible to state the conclusions arising from such an inquiry in briefest outline.

Connection with the parent movement of Reformation

Undoubtedly, the English Reformation is a significant part of the Protestant Reformation of the 16th century. Its doctrine, liturgy, and main promoters were heavily influenced by the Lutheran and Calvinistic movements on the Continent.

First Connection: Personal

The key figures of the English Reformation, including Cranmer, Barlow, Hooper, Parker, Grindal, Scory, May, Cox, Coverdale, Peter Martyr, and Martin Bucer, were in close contact and communication with Protestant leaders on the Continent. Conversely, continental reformers such as John a Lasco and Paul Fagius became friends with Cranmer and were welcomed to English universities as professors of Divinity.

Second Connection: Doctrinal

The key ideas of the Protestant Reformation, including doctrines from Luther, Melanchthon, Calvin, and Zwingli, are preserved in the literature of the English Reformation. There are nine chief doctrines that are essential and characteristic of the Protestant Reformation as a whole.

rejection of the Papacy,

denial of the **Church Infallibility,

Justification by Faith only,

supremacy and sufficiency of Scripture as Rule of Faith,

The triple Eucharistic tenet includes: (a) considering the Eucharist as a Communion or Sacrament, not a Mass or Sacrifice, except for praise or commemoration purposes; (b) rejecting the idea of Transubstantiation and the worship of the Host; and (c) denying the sacrificial role of the priesthood and the propitiatory nature of the Mass.

the non-necessity of auricular Confession,

the rejection of invoking the Blessed Virgin and the Saints,

rejection of Purgatory and omission of prayers for the dead

rejection of the doctrine of Indulgences.

Three disciplinary characteristics based on doctrine can be added:

the giving of Communion in both kinds;

the substitution of tables for altars; and

the abolition of monastic vows and the celibacy of the clergy.

The twelve doctrines and practices of the continental Reformation influenced the English Reformation to varying degrees. These ideas are reflected in Anglican formularies, and the term "Protestant" is used in the Coronation Service when the King promises to uphold "the Protestant religion as by law established." This term became popularly applied to Anglican beliefs and services. The Act of Union refers to the Churches of England and Ireland as "the Protestant Episcopal Church," a name still used by the Anglican Church in America.

Third Connection: Liturgical

The Anglican Articles were influenced by the Confession of Augsburg and the Confession of Wurtemberg. Parts of the baptismal, marriage, and confirmation services were derived from the "Simplex et Pia Deliberatio" compiled by Lutheran Hermann von Wied with the help of Bucer and Melanchthon. The Anglican ordinal was also influenced by Bucer's "Scripta Anglica", as noted by Canon Travers Smith.

Conclusion

The continental and Anglican Reformations are interwoven in this triple bond of personal, doctrinal, and liturgical aspects, despite their many and notable differences. They form part of one great religious movement.

Use of liturgical reform to deny the Sacrifice

Comparing the Anglican Prayer Book and Ordinal with the Pre-Reformation formularies they replaced reveals that the new liturgy was motivated by the same aim as the Reformation movement as a whole. This aim was to emphasize that the Lord's Supper is a Sacrament or Communion, not a Sacrifice, and to remove any indication of the sacrificial nature of the Eucharist or the Catholic belief in the Real, Objective Presence of Christ in the Host.

The Catholic liturgical forms, missal, breviary, and pontifical were in use for centuries. When making a liturgical reform, changes had to be made with reference to them. Comparing the Sarum Missal, Breviary, and Pontifical with the Anglican Prayer Book and Ordinal reveals the intention of the framers.

The Catholic Pontifical has 24 passages in the Ordination services that clearly express the sacrificial character of the priesthood. None of these were included in the Anglican Ordinal.

The Anglican Communion Service has removed about 25 points from the Ordinary of the Mass that express or imply the sacrificial nature of the Eucharist and the Real Presence of Christ as a Victim. Instead, it has replaced them with passages that are non-committal or have a Reformational character.

The new formularies intentionally exclude sacrificial and sacerdotal elements in 49 places.

(See *The Tablet*, London, 12 June, or 1897.)

Development and parties

Although the Anglican Articles and liturgy have remained largely unchanged since 1662, the life and thought of the Church of England inevitably underwent development. This development eventually outgrew, or at least strained, the historic interpretation of the formularies, due to the lack of a living authority to adapt or readjust them to newer needs or aspirations. The development was guided by three main influences.

Anglicanism's loyalty to the principles of the Reformation has produced the Low Church or Evangelical movement.

Rationalism has induced an aversion to dogmatic, supernatural, or miraculous beliefs, producing the Broad Church or Latitudinarian movement.

Catholicism has influenced Anglicanism through the High Church movement, which put forward higher and philocatholic views on Church authority, belief, and worship.

Oxford Movement

In 1833, a group of Oxford students and writers led by John Henry Newman, including John Keble, C. Marriott, Hurrell Froude, Isaac Williams, Dr. Pusey, and W.G. Ward, defended the Anglican Church against popular opposition. They aimed to establish the Anglican Church's claim to Catholicism, which required looking beyond the Reformation.

The goal was to connect the Anglican Church to Catholic tradition by linking Anglican High Church divines from the 17th and 18th centuries with certain Fathers. This was done through translations of the Fathers, works on liturgy, festivals, and a series of "Tracts for the Times", which conveyed new conceptions of churchmanship.

In "Tract 90", an attempt was made to reconcile the Anglican Articles with the teachings of the Council of Trent, similar to what was done in Sancta Clara. This resulted in a doctrinal and devotional crisis in England, not seen since the Reformation. The Oxford or Tractarian movement, which spanned from Keble's sermon on "National Apostasy" in 1833 to Newman's conversion in 1845, was a significant period in Anglican history. The fact that the movement was informally a study "de Ecclesiâ" brought the writers and readers face to face with the claims of the Church of Rome.

Many who participated in the movement, including its leader, became Catholics. Others who remained Anglicans gave a new direction to Anglican thought and worship with a pro-Catholic perspective. Research into Catholicity and the rule of faith led Newman, Oakley, Wilberforce, Ward, and others to see the need for the living voice of a Divine magisterium (the regula proxima fidei). Failing to find it in the Anglican episcopate, they sought it where it could be found.

Some people looked for guidance from the Church through written texts and definitions, but this approach relied on personal interpretation. This principle still divides people today. Pusey once said that he trusted the English Church and the Fathers, while Newman trusted the bishops, who ultimately failed him.

Anglican revival

The Oxford movement ended with Dr. Newman's conversion in 1845, but many Anglicans were deeply affected by its ideals and did not return to the narrow religious views of the Reformation. Its influence is seen in the continuous conversion of people to the Catholic faith and in the significant change in belief, temperament, and practice within the Anglican Church, known as the Anglican Revival.

Between 1860 and 1910, a growing religious movement emerged in England, seeking to Catholicize the Anglican Church. The movement claims that the Anglican Church is one with the Ancient Catholic Church and offers Anglicans everything except communion with the Holy See. The movement has won favor among many Anglicans by incorporating elements of Catholic teaching and ritual into Anglican services. Despite lacking the learning and logic of the Tractarians, this movement has earned respect and attachment from the masses through the zeal and self-sacrifice of its clergy.

The Anglican Church's advanced section sought to validate its position and overcome its isolation by seeking corporate reunion and recognition of its orders. Pope Leo XIII emphasized the need for dogmatic unity and submission to the authority of the Apostolic See for any reunion to occur. After a thorough investigation, he declared Anglican Orders "utterly null and void" in 1896, requiring all Catholics to accept this as a "fixed, settled, and irrevocable" judgment.

The Anglican Revival appropriates elements of Catholic doctrine, liturgy, and practice, as well as church vestments and furniture, to serve its purposes. The Lambeth judgment of 1891 sanctioned many of its innovations. The Revival believes that no authority in the Church of England can override practices authorized by "Catholic consent". It is a system that aspires to Catholic views while being built upon a Protestant foundation and committed to heresy and heretical communication. Although Catholics view its claims as an impious usurpation of the Catholic Church's rightful domain, the Revival plays an informal role in influencing English public opinion and familiarizing the English with Catholic doctrines and ideals.

Like the Oxford movement, it educates more pupils than it can keep, and is based on premises that will ultimately take it further than it intends to go. Its theories, including a branch theory that is rejected by the main branches, a province theory that is not recognized by other provinces, and a continuity theory that is contradicted by over twelve thousand documents in the Record Office and the Vatican Library, do not provide a stable foundation and are only temporary and transitional. While it may provide an introduction to Catholicism for the masses, it actively undermines and undoes the English Reformation.

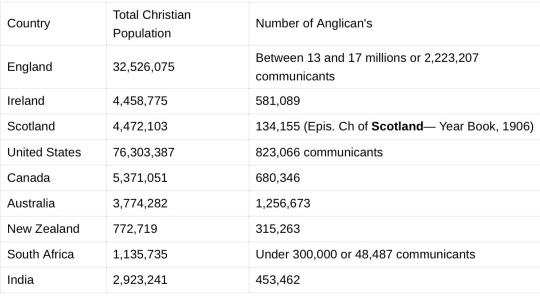

Statistics

The number of Catholics worldwide was estimated to be over 230 million in 1910, with approximately 100 million belonging to the Greek and Eastern Churches. The number of Anglicans was less than 25 million. Anglicanism is mostly concentrated in England, Ireland, Scotland, the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and India. However, its membership is a minority of the Christian population in most of these countries, with the exception of England. Anglicanism's foreign missions are generously supported and active in heathen countries.

Sources

Wilkins, Concilia (London, 1737)

Calendar of State Papers: Henry VII (London, 1862 sqq.)

Edward VI (1856 sqq.)

Elizabeth (ibid., 1863 sqq.)

Prothero, Select Statutes

Cardwell, Documentary Annals (Oxford, 1844)

Cranmer, Works

Gairdner, History of the Church of England in the XVIth Century

Dixon, Hist. of Church of England (London, 1878-1902)

Wakeman, Introduct. to Hist. of Church of England (London 1897)

Cardwell, History of Conferences (London, 1849)

Gibson, the Thirty-nine Articles

Browne, Hist. of the Thirty-nine Articles

Keeling, Liturgiae Britannicae

Gasquet and Bishop, Edward VI and the Book of Common Prayer (London, 1891)

Dowden, The Workmanship of the Prayer Book

Bulley, Variations of the Communion and Baptismal Offices

Brooke, Privy Council Judgements

Seckendorff, History of Lutheranism

Janssen, History of the German People, V, VI

Original Letters of the Reformation (Parker Series)

Zurich Letters (Cambridge, 1842-43)

Benson, Archbishop Laud (London, 1887)

Church, The Oxford Movement (London and New York, 1891)

Newman, Apologia

Liddon, Life of Pusey (London and New York, 1893-94), III

Benson, Life of Archbishop Benson

#catholic#religion#roman catholic#christianity#roman catholic history#anglican#anglicanism#Anglican Catholic#church

1 note

·

View note

Text

In memory of St Thomas More, martyr

On June 22, the Catholic Church honors the life and martyrdom of St. Thomas More, the lawyer, author and statesman who lost his life opposing King Henry VIII's plan to subordinate the Church to the English monarchy.

Thomas More was born in 1478, son of the lawyer and judge John More and his wife Agnes. He received a classical education from the age of six, and at age 13 became the protege of Archbishop John Morton, who also served an important civic role as the Lord Chancellor. Although Thomas never joined the clergy, he would eventually come to assume the position of Lord Chancellor himself.***

In 1534, Henry VIII declared that every subject of the British crown would have to swear an oath affirming the validity of his new marriage to Anne Boleyn. Refusal of these demands would be regarded as treason against the state.

In April of that year, a royal commission summoned Thomas to force him to take the oath affirming the King's new marriage as valid. While accepting certain portions of the act which pertained to Henry's royal line of succession, he could not accept the king's defiance of papal authority on the marriage question. More was taken from his wife and children, and imprisoned in the Tower of London.

For 15 months, More's wife and several friends tried to convince him to take the oath and save his life, but he refused. In 1535, while More was imprisoned, an act of Parliament came into effect declaring Henry VIII to be “the only supreme head on earth of the Church in England,” once again under penalty of treason. Members of the clergy who would not take the oath began to be executed.

In June of 1535, More was finally indicted and formally tried for the crime of treason in Westminster Hall. He was charged with opposing the king's “Act of Supremacy” in private conversations which he insisted had never occurred. But after his defense failed, and he was sentenced to death, he finally spoke out in open opposition to what he had previously opposed through silence and refusal.

More explained that Henry's Act of Supremacy, was contrary “to the laws of God and his holy Church.” He explained that “no temporal prince” could take away the prerogatives that belonged to St. Peter and his successors according to the words of Christ. When he was told that most of the English bishops had accepted the king's order, More replied that the saints in heaven did not accept it.

On July 6, 1535, the 57-year-old More came before the executioner to be beheaded. “I die the king's good servant,” he told the onlookers, “but God's first.” His head was displayed on London Bridge, but later returned to his daughter Margaret who preserved it as a holy relic of her father.*** https://www.catholicnewsagency.com/saint/st-thomas-more-499

Robert Bolt wrote a play about St Thomas More, A Man for All Seasons. Though it's written from a secular humanist point of view, it's quite a good book. I've enjoyed the 1966 film adaptation. The movie won six Academy Awards. Definitely worth your time.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Today In History:

A bit of November 3rd history…

1534 - English parliament passes Act of Supremacy: Henry VIII and subsequent monarchs become Head of Church of England

1793 - French playwright, journalist, and feminist Olympe de Gouges is guillotined

1883 - US Supreme Court decides federal courts have no jurisdiction over Native American tribal council

1906 - International Radiotelegraph Conference in Berlin selects “SOS” distress signal as the worldwide standard for help

1913 - 1st modern elastic brassiere is patented by NY socialite Mary Phelps Jacob

1952 - Clarence Birdseye markets frozen peas

1957 - Soviet Union launches Sputnik 2 with space dog Laika aboard, 1st animal in space (pictured)

1975 - US advice columnist for “Good Housekeeping” Ann Landers asks parents in a mail in survey “If you had it to do over again, would you have children?” 70% say no

0 notes

Text

On this day, 6th of July in 1535 Thomas More was executed.

On 13 April 1534, More was asked to appear before a commission and swear his allegiance to the parliamentary Act of Succession. More accepted Parliament's right to declare Anne Boleyn the legitimate Queen of England, though he refused "the spiritual validity of the king's second marriage", and, holding fast to the teaching of papal supremacy, he steadfastly refused to take the oath of supremacy of the Crown in the relationship between the kingdom and the church in England. More furthermore publicly refused to uphold Henry's annulment from Catherine.

In addition to refusing to support the King's annulment or supremacy, More refused to sign the 1534 Oath of Succession confirming Anne's role as queen and the rights of their children to succession. More's fate was sealed.While he had no argument with the basic concept of succession as stated in the Act, the preamble of the Oath repudiated the authority of the Pope.

Four days later, Henry VIII had More imprisoned in the Tower of London.

While More was imprisoned in the Tower, Thomas Cromwell made several visits, urging More to take the oath, which he continued to refuse.

The trial was held on 1 July 1535, before a panel of judges. More was offered the chance of the king's "gracious pardon" should he "reform his […] obstinate opinion". More responded that, although he had not taken the oath, he had never spoken out against it either and that his silence could be accepted as his "ratification and confirmation" of the new statutes.

Thomas Cromwell brought forth Solicitor General Richard Rich to testify that More had, in his presence, denied that the King was the legitimate head of the Church.

The jury took only fifteen minutes, however, to find More guilty.

The execution took place at Tower Hill. On the scaffold More declared "that he died the king's good servant, and and God's first.

Another comment he is believed to have made to the executioner is that his beard was completely innocent of any crime, and did not deserve the axe; he then positioned his beard so that it would not be harmed.

#thomasmore#sirthomasmore#execution#martyr#HenryVIII#anneboleyn#thomascromwell#06071535#deathanniversary#jeremynortham#thetudors#history#tudorhistory#god#actofsuccession

0 notes

Text

things that annoy me bcus i am an annoying person that has a henry viii blog and that for that reason seeing adjacent misinfo swirling online annoys me:

henry was not ‘catholic without the pope’. there literally is no such thing (i realize this makes labels rather difficult, he certainly also was not ‘protestant’, and that weird-religious-hybrid that had not existed before or in since does not go down as easy)

henry did not invest edward seymour as the duke of somerset (nor as the lord protector, for that matter....nor john dudley as that, either...)

it seems highly unlikely that he 'oversaw 72000 executions’. consider why it is that there is such a firm figure floating around for him and not other tudor monarchs. there was no official ‘execution roster’ that included everyone ever executed in england at this time. numbers we have generally come from the executions of religious martyrs (which leaders of catholicism and protestantism had great motives to preserve for posterity), executions of notable figures for treason, and executions as reprisals for rebellions. executions for “petty crimes” or repeat offenses that traditionally took place at tyburn, et al, were not so meticulously preserved.

now that we’re on that topic... there is very little indication that the years anne boleyn was queen were the pinnacle in number of tudor executions, either of her ‘enemies’ or otherwise. let’s break it down by years:

1533-36:

1533: the executions of john frith & andrew hewet (protestant martyrs, but neither here nor there): 2

1534: the executions of elizabeth barton, edward bocking, richard risby (her ‘enemies’, less than was decreed initially, at her behest according to contemporary record): 3

1535: the executions of the carthusian martyrs, thomas more, and john fisher (more arguably in the group of her opponents, although theirs was against the act of supremacy, not succession): 8

total: 13 (yeah, i was surprised, too, considering how vehemently that’s asserted)

1537-40:

john hussey, the earl of kildare+ his five uncles, pilgrimage of grace leaders, catholic martyr john forest, protestant martyrs, carthusians, thomas cromwell, treason offenses, etc.

= rounds up to around forty, likely the number tops out around 100 if you include the reprisal executions of the participants of the pilgrimage of grace, not just its leaders

#the execution one bothers me a lot bcus it's just common sense....#there's so much outrage that there's focus on executions for heresy and essentially averages taken from that (how many over how many years)#but those are the firmest numbers we have? becaus of the above reasons? of course that's what receives the focus#and of course it's used bcus it so reflects the changes in religion/ religious upheaval and to what degree over time#it entirely makes sense to use it as a metric#we go from one person executed for religion in twenty four years (henry the seventh)#to 79 for the same in nearly forty years (henry the 8th)#(estimate...do you count robert aske? etc)#two executed for religion in the six years of edward sixth#287 during the six years of mary's#189 during the 40+ years of elizabeth's#when we talk about statistics of executions for reprisals... it's probably a lot more difficult to ascertain#pilgrimage of grace vs ketts rebellion vs wyatt's rebellion#vs northern uprising#the major ones...#but anyway. for henry viii; it is rather straightforward to tally treason executions; heresy executions; rebellion executions#and it's a large number but it nowhere near approaches 72000. nor the other one that floats around now which is 57000

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Henry VIII’s rejection of the Pope’s authority in 1534 led to the setting up of a State Church in England and in Ireland. In 1560 the Act of Supremacy made Queen Elizabeth the supreme head of the Church in England and Ireland. So it became a treasonable offence to refuse to acknowledge the English monarch as head of the Church and many Catholics were put to death for their faith in both countries. Forty English martyrs were canonised in 1970 and Oliver Plunkett was canonised in 1975. In 1992 a representative seventeen Irish martyrs, chosen from a list of almost three hundred who died for their faith in the 16th and 17th centuries, were beatified by Pope John Paul II. The amount of information we know about these seventeen varies. About some, such as Archbishop Dermot O’Hurley of Cashel, we know quite a lot; about others, such as the Wexford sailors, we know little more than their names and the fact of their death. https://www.instagram.com/p/CfBx2KVru0E/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

1 note

·

View note

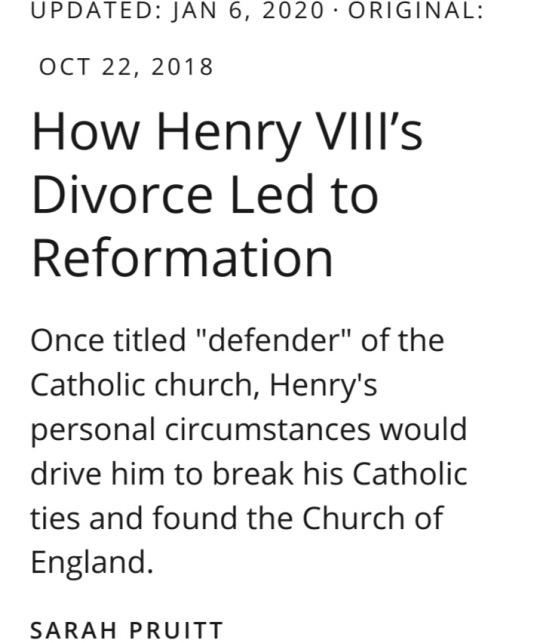

Text

When Martin Luther issued grievances about the Catholic Church in 1517, King Henry VIII took it upon himself to personally repudiate the arguments of the Protestant Reformation leader.

The pope rewarded Henry with the lofty title of Fidei Defensor, or Defender of the Faith.

Barely a decade later, the very same Henry VIII would break decisively with the Catholic Church, accept the role of Supreme Head of the Church of England and dissolve the nation’s monasteries, absorbing and redistributing their massive property as he saw fit.

So what changed? How did the former “Defender of the Faith” end up ushering in the English Reformation?

King Henry VIII wanted out from his first marriage.

Though early signs of anticlericalism had surfaced in England by the 1520s, Catholicism still enjoyed widespread popular support.

As for Henry VIII, he “had no wish and no need to break with the church,” says Andrew Pettegree, professor of History at the University of St. Andrews (U.K.).

“No need because he already enjoyed substantial power over the English church and its income...And he had no wish also, because he was personally rather pious.”

But by 1527, Henry had a big problem: His first marriage to Catherine of Aragon, had failed to produce a son and male heir to the throne.

Henry had also become infatuated with one of his wife’s ladies-in-waiting, Anne Boleyn, whose sister Mary had previously been his lover.

Anne encouraged the king’s attention, but shrewdly refused to become his mistress, setting her sights on a higher goal.

So Henry asked Pope Clement VII to grant him a divorce from Catherine.

He argued that the marriage was against God’s will due to the fact that she had briefly been married to Henry’s late brother, Arthur.

Henry faced unfavorable papal politics.

Under other circumstances, it wouldn’t have been too difficult for England’s king to get a papal dispensation to set aside his first wife and marry another in order to produce a male heir.

“There was a clear understanding among the princely houses of Europe that the continuation of the dynasty was the ruler's number one priority,” says Andrew Pettegree, professor of history at the University of St. Andrews (U.K.).

But timing was not on Henry’s side.

That same year—1527—the imperial troops of the Holy Roman Empire had attacked and destroyed Rome itself, forcing Pope Clement VII to flee the Vatican through a secret tunnel and take shelter in the Castel Sant’Angelo.

At the time, the title of Holy Roman Emperor belonged to King Charles V of Spain—Catherine of Aragon’s beloved nephew.

With the papacy almost entirely under imperial sway, Clement VII was not inclined to grant Henry a divorce from the emperor’s aunt.

But he didn’t want to completely deny Henry either, so he stretched out negotiations with the king’s minister, Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, over several years, even as Henry grew increasingly frustrated.

Thomas Cranmer and Thomas Cromwell find a Protestant solution.

It was the clergyman Thomas Cranmer and the king’s influential adviser Thomas Cromwell—both Protestants—who built a convincing case that England’s king should not be subject to the pope’s jurisdiction.

Eager to marry Anne, Henry appointed Cranmer as the Archbishop of Canterbury, after which Cranmer quickly granted Henry’s divorce from Catherine.

In June 1533, the heavily pregnant Anne Boleyn was crowned queen of England in a lavish ceremony.

Parliament’s passage of the Act of Supremacy in 1534 solidified the break from the Catholic Church and made the king the Supreme Head of the Church of England.

With Cranmer and Cromwell in positions of power and a Protestant queen by Henry’s side, England began adopting “some of the lessons of the continental Reformation,” Pettegree says, including a translation of the Bible into English.

The Crown also moved to dissolve England’s monasteries and take control of the Church’s vast property holdings from 1536-40, in what Pettegree calls “the greatest redistribution of property in England since the Norman Conquest in 1066.”

All of the property reverted to the Crown, and Henry used the windfall to reward his counselors, both Protestant and conservative, for their loyalty.

“Even Catholics are extremely tempted by the opportunity to increase their landholdings with this former monastic property,” Pettegree says.

Anne Boleyn’s daughter completed Reformation.

Anne Boleyn, of course, would fail to produce the desired son (although she gave birth to a daughter who would become Elizabeth I).

By 1536, Henry had fallen for another lady-in-waiting, Jane Seymour.

That May, after her former ally Cromwell helped engineer her conviction of adultery, incest and conspiracy against the king, Anne was executed.

In October 1537, Jane Seymour gave birth to Henry’s first male heir, the future King Edward VI, before dying of complications from childbirth two weeks later.

For the rest of Henry’s life, evangelical and conservative factions wrestled for influence—often with murderous results—but after Henry’s death in 1547, his son’s brief reign would be dominated by evangelical Protestant counselors, who were able to introduce a much more radical Reformation into England.

But Edward died young in 1553 and his Catholic half-sister, Queen Mary I, would reverse many of these changes during her reign.

It would be left to Queen Elizabeth I, the daughter of Anne Boleyn and ruler of England for nearly 50 years, to complete the Reformation her father had begun.

As for Henry VIII, he had remained a conservative Catholic with a personal hatred of Martin Luther for the rest of his life, despite the revolutionary changes effected on his behalf.

“The divorce is absolutely at the heart of the matter,” Pettegree concludes.

“Had there been no marital problems, I'm fairly certain there would have been no English Reformation, at least in Henry's lifetime.”

--------------

Act of Supremacy 1534

In 1534, Parliament passed the Act of Supremacy, which defined the right of Henry VIII to be supreme head on earth of the Church of England, thereby severing ecclesiastical links with Rome.

-------------

Modern English Transcript:

Albeit the king's majesty justly and rightfully is and ought to be supreme head of the Church of England and so is recognised by the clergy of the realm in their convocations;

Yet nevertheless for corroboration and confirmation thereof and for increase in virtue in Christ's religion within the realm of England, and to repress and uproot all errors heresies and other enormities and abuses heretofore used in the same.

Be it enacted by authority of this present Parliament that the king our sovereign lord, his heirs and successors, kings of the realm, shall be taken, accepted and reputed the only supreme head on earth of the Church of England called Anglicana Ecclesia and shall have and enjoy annexed and united to the imperial crown of this realm as well the title and style thereof, as all honours, dignities, pre-eminences, jurisdictions, privileges, authorities, immunities, profits and commodities to the said dignity of supreme head of the same Church belonging and appertaining.

And that from time to time to visit, repress, redress, reform, order, correct, restrain, and amend all such errors, heresies, abuses, offences, contempts, and enormities whatsoever they be, which by any manner [of] spiritual authority or jurisdiction ought or may lawfully be reformed, repressed redressed, ordered, corrected, restrained, or amended, most to the pleasure of Almighty God the increase of virtue in Christ's religion and for the conservation of the peace, unity, and tranquillity of this realm, any usage, custom, foreign laws, foreign authority, prescription or any other thing or things to the contrary hereof notwithstanding.

Source: National Archives UK

#Henry VIII#House of Tudor#Martin Luther#Fidei Defensor#Catherine of Aragon#Anne Boleyn#Jane Seymour#Pope Clement VII#Holy Roman Emperor King Charles V of Spain#Cardinal Thomas Wolsey#Thomas Cranmer#Thomas Cromwell#Act of Supremacy 1534#Edward VI#Elizabeth I#Mary 1#Reformation#Supreme Head of the Church of England

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Padfoot – Guardian of Graves

Padfoot… larger and more powerful than any wolf is a demon hound associated with death – A sighting of Padfoot can never be a good thing…

Big Black Dogs or Black Shuck's are seen all over the UK but Padfoot is different, he is seen along the route that Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Jacobite Army took while invading and then retreating from England.

A Brief And Simplified History Of Why Bonnie Prince Charlie Invaded England.

• The Act of Supremacy (1534), declared King Henry VIII to be the Supreme Head of the Church of England.

• Under King Edward VI (1547–1553), the church in England underwent what is known as the English Reformation, in the course of which it acquired a number of characteristics that would subsequently become recognised as constituting its distinctive "Anglican" identity.

• Queen Mary I (Bloody Mary) was Queen of England and Ireland from July 1553. She is best known for her vigorous attempt to reverse the English Reformation, Mary had over 280 religious dissenters burned at the stake in the Marian persecutions.

• After Mary's death in 1558, her re-establishment of Roman Catholicism was reversed by her younger half-sister and successor, Queen Elizabeth I.

• The following Monarchs up until 1685 were head of the Anglican Church.

• James, the Brother of King Charles II converted to Catholicism under the influence of his first wife. King Charles however demanded his (James) daughter Mary was brought up in the Anglican faith.

• In 1677 Mary married William III Prince of Orange (The Principality of Orange was, a feudal state in Provence, in the south of modern-day France)

• King Charles II died in 1685 and James his brother, became King James VII. The fact that James was a Catholic was not seen as an issue because he was 55 (a good age at the time) and His daughter Mary who was Heir to the throne was Anglican.

• On 10th June 1688, the birth of James's son and heir James Francis Edward, raised the prospect of initiating a Roman Catholic dynasty.

• Leading members of the English political class invited William of Orange and Mary to assume the English throne; after William landed in England on 5 November 1688, King James's army deserted, and he went into exile in France.

• James Francis Edward (the son of James VII) didn’t give upon his right to the throne and tried unsuccessfully to regain it in 1715. A final attempt at rebellion, led by his elder son Charles Edward Stuart, (Bonnie Prince Charlie) was made in the Jacobite rising of 1745..

• Charles launched the rebellion on 19 August 1745. The Scots agreed to invade England after Charles assured them of substantial support from English Jacobites and the French. On that basis, the Jacobite army entered England in early November, reaching Derby on 4 December, where they decided to turn back due to the fact that the reinforcements never materialised.

Well that wasn’t as brief as I expected, but History is cool and a bit of context was needed…

It’s the battle sites of Bonnie Prince Charlie’s invasion of and retreat from England where Padfoot is seen guarding the graves of the fallen.