#And with lesbians and heterosexuality. Like it’s not surprising or feminism that a lesbian’s ideal relationship with a man is to not have 1

Text

Ironically enough, Rita Mae Brown, who is well known as the author of the 1973 lesbian novel Rubyfruit Jungle and was also a founding member of the lesbian separatist Furies Collective (during which time she expressed disapproval of bisexuality), apparently continued to have sexual relationships with men, and later called “lesbian” a “misnomer” for herself and claimed most people were “degrees of bisexual.”

Which just goes to show that even some of the influential women involved in shaping quintessential “lesbian culture,” including the parts of it that professed a rejection of bisexuality, could themselves have complicated sexual practices and self-understandings which didn’t totally preclude relationships with men.

From the dissertation "Love and Liberation: Second-Wave Feminisms and the Problem of Romantic Love" by Robin Kay-Marie Payne, 2010:

Whether Brown was truly the “only visible lesbian” is certainly debatable; however, the bigger contradiction that becomes most apparent in her memoir, her diaries, and her personal correspondence was that Brown was actually a practicing bisexual. During her tenure in the Radicalesbians and The Furies, Brown had counted herself among the coterie of political lesbians who saw bisexuality as a cop-out and once wrote: “You can’t have your cake and eat it too. You can’t be tied to male privilege with the right hand while clutching to your sister with the left.” She continued, “Lesbianism is the only road toward removing yourself from male ways and beginning to learn equality.”[135] Perhaps Brown’s views had softened or maybe she counted herself among the few evolved folks who could live the ideal, despite the persistence of male supremacy. Maybe she did not count her own dalliances with men as exercises in heterosexual privilege since she did not have long-term romantic relationships with them. Perhaps she decided she would also like to have her cake and eat it too. Regardless of theoretical justifications (or lack thereof), the fact remained that after the mid-1970s, Brown sometimes engaged in sexual relationships with men. She mentioned at least twice in her diary that she had the occasional affair with a “kind and bright woman or man,”[136] and on another occasion claimed to “belong to neither camp” of straight women or lesbians “nor the bisexuals.” “I find the entire process of categorization obscene,” she wrote.[137]

Brown’s comment that she belonged to “neither camp” seemed to be a retreat from her earlier espousal of political lesbianism and all it had to offer women. Two decades later, in her memoir, she retreated even further, stating “Why it’s believed that people who physically love a member of their own sex can’t love a member of the opposite sex emotionally or physically amazes me.”[138] To an extent, this echoed arguments she had made in The Furies, that lesbians were more likely to like men as people than straight women who had more emotionally invested in them.[139] But, in that case, Brown had merely hinted that lesbian women and men who were sympathetic had the possibility of alliance and friendship. Here, she admitted, “I never minded sleeping with a man. I just minded marrying one.”[140] Interestingly, she had once sought to thwart her prying aunt’s effort to figure out if she was a lesbian by quipping, “I’m not a homosexual. I have a whimsical disregard for gender.”[141] Considering the realities of her sexual experiences, the witty retort was actually more descriptive of her identity than her staunch insistence on lesbianism as a political identity.

Despite Brown’s later admissions that she sometimes had relationships with men, it was clear that she still very much identified politically as a lesbian feminist. As she wrote in her memoir: “I’m not even a good lesbian. I’m much more bisexual, but if you want to step on my neck and call me a dyke, don’t be surprised if I sink my fangs into your ankle. I’m smart enough to know that the reality of who I am is not as important as what people perceive me to be.”[142] And, she was smart enough to understand the importance of perception in 1970, when she became a primary spokesperson for political lesbianism. Among the most vocal political lesbians who argued that not only was it expedient, but also necessary, for feminists to identify as lesbian in order to succeed in the feminist revolution, Brown later claimed that she had “hardly wanted all women to be lesbians.” On the contrary, she argued, “That would be boring. I only needed a critical mass.”[143] Having a critical mass would help ensure that there were enough women devoting themselves exclusively to the cause of feminism and it would also help to counter anti-feminist efforts to lesbian-bait feminists. If enough feminists were lesbian, homophobia would lose its effectiveness as a tool of the backlash.

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lesbian Politicization

This was published 1990 in a book called Dykes-Loving-Dykes: Dyke Separatist Politics for Lesbians Only and illustrates exactly the long-standing issue with women appropriating lesbianism, using their political beliefs to try to define female homosexual existence in relation to opposing men. The agenda, of course, is to say fuck males and to fight the ever elusive and ever changing culture of patriarchy.

That’s 100% relevant and helpful for actual homosexual females....not.

I’ll make this short though, this is just to show how feminists been appropriating lesbians and applying their values to lesbian existence.

In the 1980’s, a decade of reactionary politics, femininity became an accepted value among many Lesbians. Even many politically radical Lesbians, who I would most expect to support Lesbian self-love and self-respect, who usually call male bullshit for what it is, began to openly admire feminine ways of dressing and acting. Femininity! A patriarchal hype if there ever was one.

Lesbians who didn’t look the way you personally think is more useful for your cause probably didn’t care to make a political statement out of their existence. The point of lesbians seeking lesbian communities is to find other lesbians - with the exception of those who WANTED to seek out political radical lesbian communities. That is not an inherent aspect of our existence, and to be honest, it’s not even a large part of it as women appropriating lesbians usually populated those communities. Here is a recap of the origins of radical “lesbian” separatism:

***

[ In the late 70s a group of lesbians in Leeds, known as revolutionary feminists (RFs), made a controversial move that resonated loudly for me and many other women. They began calling for all feminists to embrace lesbianism. Appealing to their heterosexual sisters to get rid of men “from your beds and your heads”, they started a debate, which reached its height in 1981 with the publication of an infamous booklet, Love Your Enemy? The Debate Between Heterosexual Feminism and Political Lesbianism (LYE). In this, the RFs wrote that, “all feminists can and should be lesbians. Our definition of a political lesbian is a woman-identified woman who does not fuck men. It does not mean compulsory sexual activity with women.

It’s no surprise that the booklet was so controversial. “We think serious feminists have no choice but to abandon heterosexuality,” it reads. “Only in the system of oppression that is male supremacy does the oppressor actually invade and colonise the interior of the body of the oppressed.”

https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2009/jan/30/women-gayrights

“Political lesbianism originated in the late 1960s among second wave radical feminists as a way to fight sexism and compulsory heterosexuality. Sheila Jeffreys helped to develop the concept when she co-wrote “Love Your Enemy? The Debate Between Heterosexual Feminism and Political Lesbianism”[3] with the Leeds Revolutionary Feminist Group. They argued that women should abandon support of heterosexuality and stop sleeping with men, while encouraging women to rid men “from your beds and your heads.”[4] Heterosexual behavior is seen as the basic unit of the patriarchy’s political structure, lesbians who reject heterosexual behavior therefore disrupt the established political system.[5]Ti-Grace Atkinson, a radical feminist who helped to found the group The Feminists, is attributed with the phrase that embodies the movement: ‘Feminism is the theory; lesbianism is the practice.’[6]” ]

***

Lesbians’ acceptance of anything “feminine” is part of the weakening of Lesbian politics—a Lesbian parallel to the right-wing trend of het politics.

LOL good. Being a lesbian does not mean representing anything political. Also what the fuck? This is where queer activists got their penchant for calling lesbians Nazis lol. Where’s that meme that’s like, anyone I don’t like is a Nazi? lol great homophobia, Queen/dumbass.

Those Lesbians who act out the feminine model and claim it’s a contribution to Lesbian culture, a flowering forth of their “real selves,” are of course Fems

So feminine lesbians’ real selves aren’t acceptable within your framework because they trigger your contempt of gender presentation that you yourself do not have to take part of? But your “real self” - a non-lesbian pretending to be a lesbian - is commendable because you want other lesbians to act and look exactly how you do which supposedly is off-putting to patriarchy AKA you use our sexual orientation to say fuck you to men? I think not.

The het media is full of stories about the het feminist who “realizes that she doesn’t have to give up being a woman to be a success in life,” who “regrets having tried to be like a man,” and is now “rediscovering the excitement of feminine seductiveness, the fun of dressing up in high heels, make-up and skirts, and her deep need for the joys of motherhood.”

“Realizes she doesn’t have to give up being a woman to be a success in life”; “and her deep need for the joys of motherhood.” So you understand femininity = heterosexuality. This is the 80s/90s, I wonder what her opinion is now that ‘femininity’ has changed: heterosexual women wear gym clothes, lift weights, have short hair, wear no make up or minimal make up etc., and men love it. And yet I see feminists also say that heterosexual women who are like this are still trying to please men and so are still feminine even though what they’re doing and how they’re looking is not “feminine” according to the original perception. So what’s the truth about ‘femininity?’ It’s equating it to anything that heterosexual men find appealing, which changes constantly. You really want lesbians to spend time to think about how to be as unappealing to males as possible when they’re not even relevant and so don’t dominate our every thought and action (unlike you maybe because you’re not homosexual and so have to try harder?)? Please, get real.

She’s a threat to the Big Lie of “feminine woman,” and so men and their women collaborators make up all kinds of ridiculous, hateful fictions to explain away her existence. The pressure is meant to humiliate and bully her into accepting femininity, and it must put her through soul-shaking self-doubt, even if she knows other Butches.

While I do know this happens, the reason behind that is homophobia 100%, being “masculine” appearing is a red marker of homosexuality. The threat is the big lie of heterosexuality. “Feminine” lesbians were assaulted when with their partners or if found out that they are indeed homosexual, they were just less of an obvious target than “masculine” women. It’s not Oppression Olympics, this should be used to understand hate crimes against homosexual women.

Meanwhile, girls who accept femininity—the vast majority, unfortunately—are accepted as “real girls” and encouraged to take pride in their feminine ways. There are degrees of femininity, of course. Some Fem girls accept the complete emaciated drag queen sex-object ideal while others take on just enough feminine identity to still be accepted as real girls.

“Real girls.” I was definitely acknowledged as a “real girl” when I was still more “unfeminine” in my appearance and not out than I am right now being out. What degree of ‘femininity’ am I considered to exhibit now according to feminist praxis, who knows. Either way, my relatives disagree that any amount of femininity would make me a ‘normal’ female. My mother was sad toward the end of her life because she felt conflicted that I wasn’t a ‘real’ female. You know what would’ve changed her perception? Being with a man and having kids.

It means spending time, energy and money on nail polish, perfume, hair-do’s, dresses, diets, body-shaping exercises, poses and games; fantasizing yourself as the center of sexual attention, making everything into a sexual game, getting yourself further and further away from female reality, from real female Lesbian power. It means identifying more and more with het values and choosing to see yourself through men’s eyes.

I thought femininity was clothes, makeup and seeking to attract men. Then it’s wanting a family and diet and exercise, which aren’t exclusive to heterosexual men and women. But because heterosexual males find that appealing in their lives it’s considered feminine? So, again, “femininity” is anything heterosexual males find appealing in females. Got it. And that answers my question about what her thoughts probably are on contemporary “femininity.”

Most importantly, choosing to be an obvious Lesbian is about living with integrity. A Butch’s choice to resist femininity is the choice of a female who’s being true to herself, choosing to be as alive to her female self as possible, regardless of the punishments inflicted on her as a result. I find in that resistance a key to Dyke power, Dyke beauty and Dyke love.

A lesbian being an actual lesbian - not pretending to be one or basing her existence on her capability to spite heterosexual males and females - and living her damn life is living in integrity period. Associating a lesbian’s life with political intent and political values has no integrity, is manipulative and is suspect as hell.

#Catch me NOT getting pigeonholed into any fakebian separatist activism#I'll keep doing me...you do you...but when you try that political B.S. I will say something#Do not project onto us and use political ethics to do it stop using lesbians as your coping mechanisms

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

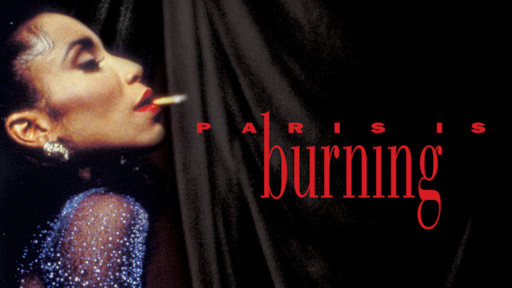

Is Paris Burning?

There was a time in my life when I liked to dress up as a male and go out into the world. It was a form of ritual, of play. It was also about power. To cross-dress as a woman in patriarchy -then, more so than now - was also to symbolically cross from the world of powerlessness into a world of privilege. It was the ultimate, intimate, voyeuristic gesture. Searching old journals for passages documenting that time, I found this paragraph:

She pleaded with him, “Just once, well every now and then, I just want to be boys together. I want to dress like you and go out and make the world look at us differently, make them wonder about us, make them stare and ask those silly questions like is he a woman dressed up like a man, is he an older black gay man with his effeminate boy/girl lover flaunting same-sex love out in the open. Don’t worry I’ll take it very seriously, I want to let them laugh at you. I’ll make it real, keep them guessing, do it in such a way that they will never know for sure. Don’t worry when we come home I will be a girl for you again but for now I want us to be boys together.”

Cross-dressing, appearing in drag, transvestism, and transsexualism emerge in a contex where the notion of subjectivity is challenged, where identity is always perceived as capable of construction, invention, change. Long before there was ever a contemporary feminist movement, the sites of these experiences were subverisve places where gender norms were questioned and challenged.

Within the white supremacist, capitalist patriarchy the experience of men dressing as women, appearing in drag, has always been regarded by the dominant heterosexist cultural gaze as a sign that one is symbolically crossing over from a realm of power into a realm of powerlessness. Just to look at the many negative ways the word “drag” is defined reconnects this label to an experience that is seen as burdensome, as retrograe and retrogressive. To choose to appear as “female” when one is “male” is always constructed in the patriarchal mindset as a loss, as a choice worthy only of ridicule. Given this cultural backdrop, it is not surprising that many black comediants appearing on television screens for the first time included as part of their acts impersonations of black women. The black woman depicted was usually held up as an object of ridicules, scorn, hatred (representing the “female” image everyone was allowed to laugh at and show contempt for). Often the moment when a black male comedian appeared in drag was the most succesful segment of a given comedian’s act (for example, Flip Wilson, Redd Foxx, or Eddie Murphy).

I used to wonder if the sexual stereotype of black men as overly sexual, manly, as “rapists”, allowed black males to cross this gendered boundary more easily than white men without having to fear that they would be seen as possibly gay or transvestites. As a young black female, I found these images to be disempowering. Thay seemed to bothallow black males to give public expression to a general misogyny, as well as to a more specific hatred and contempt toward black woman. Growing up in a world where black women wer, and still are, the objects of extreme abuse, scorn, and ridicule, I felt these impersonations were aimed at reinforcing everyone’s power over us. In retrospect, I can see that the black male in drag was also a disempowering image of black masculinity. Appearing as a “woman” within sexist, racist media was a way to become in “play” that “castrated” silly childlike black male that racist white patriarchy was comfortable having as an image in their homes. These televised images of black men in drag were never subversive; thay helped sustain sexism and racism.

It came as no surprise to me that Catherine Clement in her book, Opera, or the Undoing of Women would include a section about black men and the way their representation in opera did not allow her to neatly separate the world into gendered polarities where men and women occupied distintcly different social spaces and were “two antagonistic halves, one persecuting the other since before the dawn of time.” Looking critically at images of black men in operas she found that they were most often portrayed as victims:

Eve is undone as a woman, endlesslyy bruised, endelessly dying and coming back to life to die even better. But now I begin to remember hearing figures of betrayed, wounded men; men who ham; men who have women’s troubles happen to them; men who have the status of Eve, as if they had lost their innate Adam. These men die like heroines; down on the ground they cry and moan, they lament. And like heroines they are surrounded by real men, veritable Adams who have cast them down. Thay partake of feminity: excluded, marked by some initial strangeness. Thay are doomed to their undoing.

Many heterosexual black men in white supremacist patriarchal culture have acted as though the primary “evil” of racism has been the refusal of the dominant culture to allow them full access to patriarchal power, so that in sexist terms thay are compelled to inhabit a sphere of powerlessness, deemed “feminine”, hence thay have perceived themselves as emasculated. To the extent that black men accept a white supremacist sexist representation of themselves as castrated, without phallic power, and therfore pseudo-females, thay will need to overly assert a phallic misogynist masculinity, one rooted in contempt for the female. Much black male homophobia is rooted in the desire to eschew connection with all things deemed “feminine” and that would, of course, include black gay men. A contemporary black comedian like Eddie Murphy “proves” his phallic power by daring to publicly ridicule women and gays. His days of appearing in drag are over. Indeed it is the drag queen of his misogynist imagination that is most often the image of black gay culture he evokes and subjects to comic homophobic assault -one that audiences collude in perpetuating.

For black males to take appearing in drag seriously, be they gay or straight, is to oppose a heterosexist representation of black manhood. Gender bending and blending on the part of black males has always been a critique of phalocentric masculinity in traditional black experience. Yet the subversive power of those images is radically altered when informed by a racialized fictional construction of the “feminine” that suddenly makes the representation of whiteness as crucial to the experience of female impersonation as gender, that is to idealization of white womanhood. This is brutally evident in Jennie Livingston’s new film Paris is burning. Within the world of the black drag ball culture she deicts, the idea of womanness as feminity is totally personified by whiteness. What viewers witness is not black men longing to impersonate or even to become like “real” black women but their obsession with an idealized fetishized vision of feminity that is white. Called out in the film by Dorian Carey, who names it by saying no black drag queen of his day wanted to be Lena Horne, he makes it clear that the feminity most sought after, most adored, was that perceived to be the exclusive property of whte womanhood. When we see visual representations of womanhood in the film (images torn from magazines and posted on walls in living space) they are, with rare exceptions, of white women. Significantly, the fixation on becoming as much like a white female as possible implicitly evokes a connection to a figure never visible in this film: that of the white male patriarch. And yet if the class, race, and gender aspirations expressed by the drag queens who share their deepest dreams is always longing to be in the position of the ruling-class woman then that means there is also thedesire to act in partnership with the ruling-class white male.

This combination of class and race longing that privileges the “feminity” of the ruling-class white woman, adored and kept, shrouded in luxury, does not imply a critique of patriarchy. Often it is assumed that the gay male, and most specifically the “queen”, is both anti-phallocentric and anti-patriarchal. Marilyn Frye’s essay, “Lesbian feminism and Gay Rights”, remains one of the most useful critical debunkings of this myth. Writing in The Politics of Reality, Frye comments:

One of thing which persuades the straight world that gay men are not really men is the effeminacy of style of some gay men and the gay institution of the impersonation of women, both of which are associated in the popular mind with male homosexuality. But as I read it, gay men’s effeminacy and donning of feminine apparel displays no love of or identification with women or the womanly. For the most part, this femininity is affected and is characterized by thatrical exaggeration. It is a casual and cynical mockery of women, for whom feminity is the trapping of oppresion, but it is also a kind of play, a toying with that which is taboo.. What gay male affectation of femininity seems to be is a serious sport in which men may exercise their power and control over the feminine, much as in other sports... But the mastery of the feminine is not feminine. It is masculine..

Any viewer of Paris is Burning can neither deny the way in which its contemporary drag balls have the aura of sports events, aggressive competitions, one team (in this case “house”) competing another etc., nor ignore the way in which the male “gaze” in the audience is directed at participants in a manner akin to the objectifying phallic stare straight men direct at “feminine” women daily in public spaces. Paris is Burning is a film that many audiences assume is inherently oppositional because of its subject matter and the identity of the filmmaker. Yet the film’s politics of race, gender, and class are played out in ways that are both progressive and reactionary.

When I first heard that there was this new documentary film about black gay men, drag queens, and drag balls I was fascinated by the title. It evoked images of the real Paris on fire, of the death and destruction of a dominating white western civilization and culture, an end to oppressive Eurocentrism and white supremacy. This fantasy not only gave me a sustained sense of plearure, it stood between me and the unlikely reality that a young white filmmaker, offering a progresssive vision of “blackness” from the standpoint of “whiteness”, would receive the positive press accorded Livingston and her film. Watching Paris is Burning, I began to think that the many yuppie-looking, straight-acting, pushy, predominantly white folks in the audience were there because the film in no way interrogates “whiteness”. These folks left the film saying it was “amazing”, “marvelous”, “incredibly funny”, worthy of statements like, “Didn’t you just love it?” And no, I didn’t just love it. For in many ways the film was a graphic documentary portrait of the way in which colonized black people (in this case black gay brothers, some of whom were drag queens) worship at the throne of whiteness, even when such worship demands that we live in perpetual self-hate, steal, lie, go hungry, and even die in its pursuit. The “we” evoked here is all of us, black people/people of color, who are daily bombarded by a powerful colonizing whiteness that seduces us away from ourselves, that negates that ther is beauty to be found in any form of blackness that is not imitation whiteness.

The whiteness celebrated in Paris is Burning is not just any old brand of whiteness but rather that brutal imperial ruling-class capitalist patriarchal whiteness that presents itself -its way of life- as the only meaningful life there is. What would be more reassuring to a white public fearful that marginalized disenfracnhised black folks might rise any day now and make revolutionary black liberation struggle a reality than a doumentary affirming that colonized, victimized, exploited, black folks are all too willing to be complicit in perpetuating the fantasy that ruling-class white culture is the quintessential site of unrestricted joy, freedom, power, and pleasure. Indeed it is the very “pleasure” that so many white viewers with class privilege experience when watching this film that has acted to censor dissenting voices who find the film and its reception critically problematic.

In Vincent Canby’s review of the film in the New York Times he begins by quoting the words of a black father to his homosexual son. The father shares that it is difficult for black men to survive in a racist society and that “if you’re black and male and gay, you have to be stronger that you can imagine”. Beginning his overwhelmingly positive review with the words of a straight black father, Canby implies that the film in some way documents such strenght, is a portrait of black gay pride. Yet he in no way indicates ways this pride and power are evident in the work. Like most reviewers of the film, what he finds most compelling is the pageantry of the drag balls. He uses no language identifying race and class perspectives when suggesting at the end of his piece that behind the role-playing “there is also a terrible sadness in the testimony”. This makes it appear that the politics of ruling-class white culture are solely social and not political, solely “aesthetic” questions of choice and desire rather that expressions of power and privilege. Canby does not tell readers that much of the tragedy and sadness of this film is evoked by the willingness of black gay men to knock themselves out imitating a ruling-class culture and power elite that is one of the primary agents of their oppression and exploitation. Ironically, the very “fantasies” evoked emerge from the colonizing context, and while marginalized people often appropriate and subvert aspects of the dominant culture, Paris is Burning does not forcefully suggest that such a process is taking place.

Livingston’s film is presented as though it is a politically neutral documentary providing a candid, even celebratory, look at black drag balls. And it is precisely the mood of celebration that masks the extent to which the balls are not necessarily radical expresssions of subverive imagination at work undemining and challenging the status quo. Much of the film’s focus on pageantry takes the ritual of the black drag ball and makes it spectacle. Ritual is that ceremonial act that carries with it meaning and significance beyond what appears, while spectacle functions primarily as entertaining dramatic display. Those of us who have grown up in a segregated black setting where we participated in diverse pageants and rituals know that those elements of a given ritual that are empowering and subversive may not be readily visible to an outsider looking in. Hence it is easy for white obsevers to depict black rituals as spectacle.

Jennie Livingston approaches her subject matter as an outsider looking in. Since her presence as white woman/lesbian filmmaker is “absent” from Paris is Burning it is easy for viewers to imagine that they are watching an ethnographic film doumenting the life of black gay “natives” and not recognize that they are watching a work shaped and formed bya a perspective and standpoint specific to Livingston. By cinematically masking this reality (we hear her ask questions but never see her), Livingston does not oppose the way hegemonic whiteness “represents” blackness, but rather assumes an imperial overseeing position that is in no way progressive or counter-hegemonic. By shooting the film using a conventional approach to documentary and not making clear how her standpoint breaks with this tradition, Livingston assumes a privileged location of “innocence”. She is represented both in interviews and reviews tender-hearte, mild-mannered, virtuous white woman daring to venture into a contemporaty “heart of darkness” to bring back knowledge of the natives.

A review in the New Yorker declares (with no argument to substatiate the assertion) that “the movie is a sympathetic observation of a specialized, private world”. An interview with Livingston in Outweek is titled “Pose, She Said” and we are told in the preface that she “discovered the Ball world by chance”. Livingston does not discuss her interest and fascination with black gay subculture. She is not asked to speak about what knowledge, information, or lived understanding of black culture and history she possessed that provided a background for her work or to explain what vision of black life she hoped to convey and to whom. Can anyone imagine that a black woman lesbian would make a film about whete gay subculture and not be asked these questions? Livingston is asked in the Outweek interview, “How did you build up the kind of trust where people are so open to talking about their personal experiences?” She never answers this question. Instead she suggests that she gains her “credibility” by the intensity of her spectatoship, adding, “I also targeted people who wer articulate, who had stuff they wanted to say and were very happy that anyone wanted to listen”. Avoiding the difficult questions undelying what it means to be a white person in a white supremacist society creating a film about any aspect of black life. Livingston responds to the question, “Didn’t the fact that you’re a white lesbian going into a world of Black queens and street kids make that [the interview process] difficult?” by implicitly evoking a shallow sense of universal connection. She responds, “If you know someone over a period of two years, and thay still retain their sex and their race, you’ve got to be a pretty sexist, racist person”. Yet it is precisely the race, sex, and sexual practices of black men who are filmed that is the exploited subject matter.

So far I have read no interviews where Livingston discusses the issue of appropriation. And even though she is openly critical of Madonna, she does not convey how her work differs from Madonna’s apropriation of black experience. To some extent it is precisely the recognition by mass culture that aspects of black life, like “voguing”, fscinate white audiences that creates a market for both Madonna’s product and Livingston’s. Unfortunately, Livingston’s comments about Paris is Burning do not convey serious thought about either the political and aesthetic implications of her choice as a white woman focusing on an aspect of black life and culture or the way racism might shape and inform how she would interpret black experience on the screen. Reviewers like Georgia Brown in the Village Voice who suggest that Livingston’s whiteness is “a fact of nature that didn’t hinder her research” collude in the denial of the way whiteness informs her perspective and standpoint. To say, as Livingston does, “I certainly don’t have the final word on the gay black experience. I’d love for a black director to have made this film” is to oversimplify the issue and to absolve her of responsibility and accountability for progressive critical reflection and it implicitly suggests that there would be no difference between her work and that of a black director. Undrlying this apparently self-effacing comment is cultural arrogance, for she implies not only that she has cornered the market on the subject matter but that being able to make films is a question of personal choice, like she just “discovered” the “raw material” before a black director did. Her comments are disturbing because thay reveal so little awareness of the politics that undergird any commodification of “blackness” in this society.

Had Livingston approached her subject with greater awareness of the way white supremacy shapes cultural production -determining not only what representations of blackness are deemed acceptable, marketable, as well worthy of seeing- perhaps the film would not so easily have turned the black drag ball into a spectacle for the entertainment of those presumed to be on the outside of this experience looking in. So much of what is expressed in the film has to do with questions of power and privilege and the way racism impedes black progresss (and certainly the class aspirations of the black gay subculture depicted do not differ from those of other poor and underclass black communities). Here, the supposedly “outsider” position is primarily located in the experience of whiteness. Livingston appears unwilling to interrogate the way assuming the position of outsider looking in, as well as interpreter, can, and often does, pervert and distort one’s pespective. Her ability to assume such a position without rigorous interrogation of intent is rooted in the politics of race and racism. Patricia Williams critiques the white assumption of a”neutral” gaze in her essay “Teleology on the Rocks” included in her new book The Alchemy of Race and Rights. Describing taking a walking tour of Harlem with a group of white folks, she recalls the guide telling them they might “get to see some services” since “Easter Sunday in Harlem is quite a show”. William’s critical observations are relevant to any discussion of Paris is Burning:

What astonished me was that no one had asked the churches if they wanted to be sared at like living museums. I wondered what would happen if a group of blue-jeaned blacks were to walk uninvited into a synagogue on Passover or St. Anthony’s of Padua during high mass -just to peer, not pray. My feeling is that such activity would be seen as disresectful, at the very least. Yet the aspect of disrespect, intrusion, seemed irrelevant to this well-educated, affable group of people. They deflected my observation with comments like “We just want to look”, “No one will mind”, and “There’s no harm intended”. As well-intentioned as they were, I was left with the impression that no one existed for them who could not be governed by their intentions. While acknowledging the lack of apparent malice in this behavior, I can’t help thinking that it is a liability as much as a luxury to live without interaction. To live so completely impervious to one’s own impact on others is a fragile privilege, which over time relies not simply on the willingness but on the inability of others -in this case blacks- to make their displeasure heard.

This insightful critique came to mind as I reflected on why whites could so outspokenly make their pleasure in this film heard and the many black viewers express discontent, raising critical questions about how the film was made, is seen, and is talked about, who have not named their displearure publicly. Too many reviewers and interviewers assume not only that there is no need to raise pressing critical questions about Livingston’s film, but act as though she somehow did this marginalized black gay subculture a favor by bringing their experience to a wider public. Such a stance obscures the substantial rewards she has received for this work. Since so many of the black gay men in the film express the desire to be big stars, it is easy to place Livingston in the role of benefactor, offering these “poor black souls! a way to realize their dreams. But it is this current trend in producing colorful ethnicity for the white consumer appetite that makes it possible for blackness to be commodified in unprecedented ways, and for whites to appropriate black culture without interrogating whiteness or showing concern for the displeasure of blacks. Just as white cultural imperialism informed and affirmed the adventurous journeys of colonizing whites into the countries and cultures of “dark others”, it allows white audiences to applaud representations of black culture, if they are satisfied with the images and habits of being represented.

Watching the film with a black woman friend, we were disturbed by the extent to which white folks around us were “entertained” and “pleasured” by scenes we viewed as sad and at times tragic. Often individuals laughed at personal testimony about hardship, pain, loneliness. Several times I yelled out in the dark: “What is so funny about this scene? Why are you laughing?” The laughter was never innocent. Instead it undermined the seriousness of the film, keeping it always on the level of spectacle. And much of the film helped make this possible. Moments of pain and sadness were quickly covered up by dramatic scenes from drag balls, as though there were two competing cinematic narratives, one displaying the pageantry of the drag ball and the other reflecting on the lives of participants and value of the fantasy. This second narrative was literally hard to hear because the laughter often drowned it out, just as the sustained focus on elaborate displays at balls diffused the power of the more serious narrative. Any audience hoping to be entertained would not be as interested in the true life stories and testimonies narrated. Much of that individual testimony makes it appear that the characters are estranged from any community beyond themselves. Families, friends, etc. are not shown, which adds to the representation of these black gay men as cut off, living on the edge.

It is useful to compare the portraits of their lives in Paris is Burning with those depicted in Marlon Riggs’ compelling film Tongues Untied. At no point in Livingston’s film are the men asked to speak about their connections to a world of family and community beyond the drag ball. The cinematic narrative makes the ball center of their lives. And yet who determines this? Is this the way the black men view their reality or is this the reality Livingston constructs? Certainly the degree to which black men in this gay subculture are portrayed as cut off from a “real” world heightens the emphasis on fantasy, and indeed gives Paris is burning its tragic edge. That tragedy is made explicit when we are told that the fair-skinned Venus has been murdered, and yet there is no mourning of him/her in the film, no intense focus on the sadness of this murder. Having served the purpose of “spectacle” the film abandons him/her. The audience does not see Venus after the murder. There are no scenes of grief. To put it crassly, her dying is upstaged by spectacle. Death is not entertaining.

For those of us who did not come to this film as voyeurs of black gay subculture, it is Dorian Carey’s moving testimony throughout the film that makes Paris is Burning a memorable experience. Cary is both historian and cultural critic in the film. He explains how the balls enabled marginalized black gay queens to empower both participants and audience. It is Carey who talks about the significance of the “star” in the life of gay black men who are queens. In a manner similar to critic Richar Dyer in his work Heavenly Bodies, Carey tells viewers that the desire for stardom is an expression of the longing to realize the dream of autonomous stellar individualism. Reminding readers that the idea of the individual continues to be a major image of what it means to live in a democratic world, Dyer writes:

Capitalism justifies itself on the basis of freedom (separateness) of anyone to make money, sell their labour how they will, to be able to express opinions and get them heard (regardless of wealth and social position). The openness of society is assumed by the way that we are addressed as individuals -as consumers (each freely choosing to buy, or watch, what we want), as legal subjects (equally responsible before the law), as political subjects (able to make up our minds who is to run society). Thus even while the notion of the individual is assailed on all sides, it is a necessary fiction for the reproduction of the kind of society we live in... Stars articulate these ideas of personhood.

This is precisely the notion of stardom Carey articulates. He emphasizes the way consumer capitalism undermines the subversive power of the drag balls, subordinating ritual to spectacle, removing the will to display unique imaginative costumes an the purchased image. Carey speaks profoundly about the redemptive power of the imagination in black life, that drag balls were traditionally a place wher the aesthetics of the image in relation to black gay life could be explored with complexity and grace.

Carey extols the significance of fantasy even as he critiques the use of fantasy to escape reality. Analyzing the place of fantasy in black gay subculture, he links that experience to the longing for stardom that is so pervasive in this society. Refusing to allow the “queen” to be Othered, he conveys the message that in all of us resides that longing to transcend the boundaries of self, to be glorified. Speaking about the importance of drag queens in a recent interview in Afterimage, Marlon Riggs suggests that the queen personifies the longing everyone has for love and recognition. Seeing in drag queens “a desire, a very visceral need to be loved, as well as a sense of the abject loneliness of life where nobody loves you”, Riggs contends “this image is real for anybody who has been in the bottom spot where they’ve been rejected by everybody and loved by nobody”. Echoing Carey, Riggs declares: “What’s real for them is the realization that you have to learn to love yourself”. Carey stresses that one can only learn to love the self when one breaks through illusion and faces reality, not by escaping into fantasy. Emphasizing that the point is not to give us fantasy but to recognize its limitations, he acknowledges that one must distinguish the place of fantasy in ritualized play from the use of fantasy as a means of escape. Unlike Pepper Labeija who constructs a mythic world to inhabit, making this his private reality, Carey encourages using the imagination creatively to enhance one’s capacity to live more fully in a world beyond fantasy.

Despite the profound impact he makes, what Riggs would call “a visual icon of the drag queen with a very dignified humanity”, Carey’s message, if often muted, is overshadowed by spectacle. It is hard for viewers to really hear this message. By critiquing absorption in fantasy and naming the myriad ways pain and suffering inform any process of self-actualization, Carey’s message mediates between the viewer who longs to voyeruristicly escape into the film, to vicariously inhabit that lived space on the edge, by exposing the sham, by challenging all of us to confront reality. James Baldwin makes the point in The Fire Next Time that “people who cannot suffer can never grow up, can never discover who they are”. Without being sentimental about suffering, Dorian Carey urges all of us to break through denial, through the longing for an illusory star identity, so that we can confront and accept ourselves as we really are -only then can fantasy, ritual, be a site of seduction, passion, and play where the self is truly recognized, loved, and never abandoned or betrayed.

Bell Hooks

youtube

youtube

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

confession: i’m constantly tempted to start identifying as nb. i have a very confused mind. few things make sense to me. i’m easily manipulated. it’s a constant struggle to remind myself of my own ideals and beliefs. the only thing that has kept me on this side of the gender debate is the logical words of my radfem sisters.

when i was a sophomore in college, i met a girl, a fellow lesbian who would later become one of the best friends i’d ever had. one night we were cooking bacon and eggs in the shitty, stinky dorm kitchen and we just....had a straightforward conversation about sexuality. i’d later learn she was super nervous about talking to me like this because i’d apparently said something disapproving of radfems earlier in the year, although i didn’t even remember having a strong stance on the topic, and was even leaning more towards the radical side just by virtue of my common sense.

but we had this conversation, and this really simple, one hour conversation is what completely changed my mind and changed my life. recently i’d been having a crisis of gender. i started calling myself nonbinary online and to a few friends for a couple of months. i was genuinely considering coming out as trans because i thought i couldn’t relate to girls because i didn’t like feminine clothing or feminine toys as a child. i would often play as boy characters as a little kid, making my cousins and sister call me “he” and i only hung out with boys up until middle school because i found girls intimidating and difficult to relate to, although elementary school was the first time i had romantic thoughts about a girl.

but back to this conversation i had. i’d literally never thought about sexuality like this before because by then i’d already been partially brainwashed by transactivists even though i had no involvement in that community and really didn’t like the few trans people i knew (i found them whiny, self-absorbed, and thin-skinned). but what my friend and i discussed was basically that there are only two sexes, so you can only be attracted to the same, the opposite, or both. it’s simple radfem ideology, and something that i take as common sense now, but it completely shattered my worldview. it felt like waking up from a dream or a fog. everything made sense after that, because i was basing things on facts rather than abstraction. i stopped questioning if i was transgender, something that had brought me a great deal of distress and confusion, and started enjoying being a woman again as i had in childhood (i’d always been very big on girl power and feminism until i started to learn about transgenderism and gender theory).

the summer after that conversation was when i came out as bisexual and started delving into radblr. i followed a few lesbian positivity blogs because i considered myself mostly attracted to women. that was when i learned about compulsory heterosexuality and went on that whole journey, which eventually led to me realizing i’m lesbian. it’s actually quite surprising to me now how quickly that initial search for lesbian positivity and celebration of same sex attraction led me down the rabbit hole of “lesbians aren’t attracted to males” which eventually led to full on gender criticism and radical feminism. i’ve been here ever since and i don’t plan on leaving any time soon, and i owe a lot of that to the irl gender critical friends i’ve made along the way. this is something that genderists will never understand: hushed conversations in darkened rooms in fear of being outed against your community for WrongThink and Thought Crimes, feeling like a secret underground communist reading circle in imperial russia, hysterical giggling by lamplight with another girl as you realize you’re both demonized for being ssa, fearing that people underneath her balcony will overhear your conversation and out you as being bigots for talking about your shared experiences as vagina fetishists. these are some of my most treasured and cherished moments that i wouldn’t trade for a lifetime of living as a wannabe man. if i could have my ideal body and my ideal voice and be seen as a man by society, it wouldn’t equal a single minute of those dark, hushed conversations full of shared pain and shared anger and shared sisterhood. i wouldn’t trade these things for any of the false and empty things that transgenderism promises the lost and confused women of this world.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Film Review of Wendy Jo Carlton’s Good Kisser

Shengci (Tiffany) Lyu

Habibe Burce Baba

GNDS 125

13 February 2020

A Film Review of Wendy Jo Carlton’s Good Kisser

Good Kisser, an American lesbian feature film directed by Wendy Jo Carlton in 2019, presents in the Reelout film festival. The film portrays one random night in Seattle; the dramatic relationship is shaping between three lesbians: Jenna, her girlfriend Kate, and Mia. Carlton successfully expands modern feminism in her movie by using threesome plot to imply self-determination and presenting erotic scenes without any male gaze; however, her development is hindered since she excludes races in the film.

Good Kisser focuses on a lesbian couple, Jenna and Kate, seeking further romance and freshness after a two years relationship. Kate introduces Jenna to Mia and plans to have a threesome. Jenna is nervous and anxious at first; she becomes more relaxed as Kate and Mia start to flirting and drinking. However, Jenna realizes threesome is still too difficult for her before three of them reach the passionate climax. Meanwhile, Kate’s secret is exposed. Finally, Jenna decides to get over this night and leave Kate instead of facing the love triangle and betrayal.

By using lesbian threesome to imply self-determination, Carlton effectively expands modern feminism in Good Kisser. In Polyamory or Polyagony? Jealousy in Open Relationships, Deri states, “feminism is ultimately about self-determination for women” (184). She further supports her argument by interviewing different participants. There are many answers, but most of the participants believe that feminism reflects in upholding polyamory practice and the ideals of self-determination, non-possessiveness, gender equality, and sexual freedom (Deri 186). In other words, women need to be able to make decisions for themselves rather than being subordinate to males or patriarchy, especially on the circumstance involves sex. In Carlton’s film, Jenna, Kate and Mia are queers (the film didn’t demonstrate they are bisexual or not) who plan to have a threesome. The freedom of sex and sexual orientation are the features that the three characters have in common. They determined who they are and what they are going to do. Carlton uses such a theme to deliver and support modern feminism onscreen effectively.

Carlton also expands modern feminism by presenting erotic scenes without any male gaze. In the lecture, the male gaze is defined as “the notion that films are constructed from and for the perspective of a male heterosexual viewer such that women are always displayed as objects for men's gaze, rather than as independent entities whose value is distinct from how they are viewed by men” (OnQ Module 3). For example, like pornography, the female is always stereotyped, exploited, and objectified as" meat "in sexualized images and videos (Ley ); the sexual organs of females are emphasized. However, under the same theme of having sex, one of the surprising facts of Good Kisser is that Carlton portrays flirting and sex scenes as the film's central part without giving audiences a pornographic feeling. All the nudity shots combine with well-choosing sounds and aesthetic cinematography. The three main characters are showing their rights of sexual autonomy and female values to audiences rather than showing their “meat” to attract attention. All the evidence above makes clear that Carlton's ideal audience is not the heterosexual male; she stands on the opposite side of the male gaze. She expands the idea that females should not be objectified to her audiences by avoiding the male gaze.

Although Carlton expands modern feminism to her audiences successfully, her development is hindered since she excludes races from her movie. Kimberle Crenshaw creates intersectionality in 1989, describes different systems of power, and how they intersect each other to set up different levels of discrimination (OnQ Module 2). Kaufman states, “[it is important to apply it] because these [system of powers] of inequality are intimately and complexly tied together. Knowing that these systems of oppression work in cumulative ways means that we must take a cumulative approach to address them. We have to address all of them simultaneously” (Kaufman). However, such an approach is not to be seen in Good Kisser. In the film, Yuka, an American Asian taxi driver, a supporting role, is the only non-white person within a total of five characters. The lack of race awareness in Good Kisser reinforces White’s privilege. It may give audiences an illusion that only White can enjoy their rights of being a lesbian in America due to their race is dominant. Peter also sees the disadvantages of this problem in feminism; he says, “ black women do not only suffer sexism in one instance and racism in another instance. Instead, they must constantly deal with the combined consequences of both sexism and racism, among others” (Kaufman). Therefore, due to the intersection of unequal powers creates different levels of discrimination, races should be considered when mentioning modern feminism.

In contrast, Marc Cherry’s web television series Why Women Kill presents problems in an intersectional approach successfully. One of the main characters, Taylor Harding, a black bisexual feminist and a middle-class lawyer, she also involves in an open marriage. Such a background that contains race, sexual orientation, and class will create more conflicts in the plot since the character is forced to meet a higher level of discrimination. It will attract audiences who share the same identity or in a similar system of power with the character as well.

In summary, this review argues that Carlton displays modern feminism to her audience by employs the lesbian threesome and avoiding the male gaze in the sex scene, but she excluded races from her project. In the long run, the intersectional representation is necessary if directors aim to eliminate sexism and other prejudices. As the study by Audre Lorde provides that “ignoring the differences of [the] race between women and the implications of those differences presents the most serious threat to the mobilization of women's joint power”(117). In the film, Jenna finds her way after the torturing long night. I hope that with everyone's joint efforts, the social stress of sexism, racism, homophobia, and so on will find its solution soon.

Word counts: 997

Work Cited

Deri, Jillian. “12. Polyamory or Polyagony? Jealousy in Open Relationships.” Emotions Matter, 2012, pp. 223–239., doi:10.3138/9781442699274-016. Accessed 11 Feb. 2020.

Kaufman, Peter. “Intersectionality for Beginners.” Every Sociology Blog, 2018, everydaysociologyblog.com/2018/04/intersectionality-for-beginners.html#more.

Ley, David. “Misogyny in Porn: It’s Not What You Think.” Psychology Today, Sep 04. 2019, psychologytoday.com/ca/blog/women-who-stray/201909/misogyny-in-porn-it-s-not-what-you-think. Accessed 11 Feb. 2020.

Lorde, Audre. “Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference.” Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. Freedom, CA: Crossing Press, 1984. Pp. 114-123.

OnQ, Module 2: Feminist Foundations week 3, onq.queensu.ca/d2l/le/content/377345/viewContent/2174088/View. Accessed 11 Feb. 2020.

---. Module 3: Pop Culture as Industry week 4, onq.queensu.ca/d2l/le/content/377345/viewContent/2174072/View. Accessed 11 Feb. 2020.

0 notes

Text

Lit Review Draft 2

What Is the Correlation Between Sexual Orientation and Music Taste?

Is there a history of correlation between sexual orientation and certain genres of music? Is there even reason to believe that this correlation would exist? Do the spheres of music and sexual orientation overlap in any ways? These are the supporting questions to my main inquiry which I set out to answer through my secondary research. To this end, I researched the overlap of aspects of music and sexual orientation, the interwoven history of sexual orientation and the aesthetics of musicians, and the public impression of sexual orientation among music genres.

Sexual Orientation, Presentation, and Music

Presentation and aesthetic is regarded as an important aspect of belonging within groups, and the perception of minority sexuality groups is no different in this regard. Certain behaviors, appearances, names, voices, and more are frequently considered to belong to specific genders or sexualities, no matter how true that assumption may actually be. While these assumptions affect the groups that gravitate towards these aspects of personal presentation, they also affect which groups gravitate away. Young straight men seem to easily fall into this avoidant group, especially in situations where they believe they are being judged by male peers (Abramo, 2011). Abramo’s observations with high-school aged boys seemed to show an assumption among young straight men that having certain presentations in music, like using the head voice or singing softer lyrics, imply damaged or abnormal masculinity, and cause them to become defensive to avoid the ridicule of being assumed as not heteronormative.

Conversely, many music artists intentionally evoke queer presentation as a method of performance. Artists like The Scissor Sisters utilize the colorful, purposefully overblown aesthetic of camp to express queer narratives and experiences through both their music and their bodies. Rappers like Jwl B reveal their entire body on stage, showing the real form of queer bodies, not the idealized and pornographic images of performers often edited or circulated beyond the control of the original person. Especially for non-straight performers, taking charge of their own bodies and aesthetic and pushing them away from heteronormative expectations is an important part of the declaration of the unique queer experience (Miller, 2011).

Aesthetics that are attributed to minority or marginalized groups are important to music creators and consumers, both in terms of identifying groups that are close to your own identification and in terms of designating groups which heteronormative individuals are afraid to engage with for fear of their own sexuality being questioned. This divide by aesthetic may point to a correlation between members of certain sexualities and creators and music in certain genres.

The History of Sexuality as an Aesthetic among Music Creators and Performers

While individuals of minority sexualities and gender presentations have existed so long as to have explicit reference made to them in ancient myth and art, serious and anti-homophobic scholarly thought into the presence of queer artists in music and theatre was not even starting to be normalized until the late 1970s, aided by the influential article Britten and Grimes published in the Musical Times. Author Brett breaks down the opera Peter Grimes musically, stylistically, and in story, pointing out a queer narrative of rejection and fear of discovery stemming from both the main character and the author himself. Though the article is short and refrains from even mentioning homosexuality until nearly the last page, it still features a strong and unflinching depiction of the fear of discovery felt by gay creators and the rejection they experience upon coming out. This intentional lack of queer aesthetic by queer creators in theatre at the time still displayed a desire to be known, disguised beneath other factors but still desperate to be recognized by those who would understand the fear and shame that being queer carried in their society (Brett, 1977).

The history of feminism’s rise goes hand-in-hand with this rise of queer theory and the fight for acceptance. While Brett penned one of the first scholarly articles to take non-straight identity seriously in music theory and theatre, queer and feminist creators had already long begun the fight to be seen and not dismissed in music culture, striking out boldly. The Stonewall Riots sparked an emergence into the public conscious of women led and lesbian-feminist bands, record labels, and production companies, and disco was born as the voice of gay liberation, specifically for and by gay people of color (Brett, Wood, and Hubbs, 2012). The 1980s saw a counter-period of silencing of gay musicians and aesthetic, which then re-emerged with a vengeance with the rise of urgent anti-AIDS activism, and saw kick-back in the form of forcible outings of musicians in the 1990s (Brett, Wood, and Hubbs, 2012). Into the modern day queer and feminine aesthetic is degraded in popular media, even as it advocates true acceptance beyond the music industry, but is once more beginning to pick up steam with the modern push for equality.

The history of sexual orientation as a presentation and aesthetic in music is one of rebellion and advocacy. When who you are is seen as lesser, it is easy to gravitate towards spaces which display people like you and acceptance for your identity. It is possible that the history of queer acceptance and rebellion among certain genres could carry into the modern day, leading to genres with more queer representation among their musicians and listeners.

Sexual Orientation Among Listeners and the Public

There is certainly a precedence for the idea that certain individuals of certain beliefs or orientations would be drawn to certain music, for sound, artist, or aesthetic. Marketing tactics targeted at music-listening audiences have found it highly effective to hone in on fans of specific artists for political, social, and commercial messages (Waldrip, 2017). With artists holding such influential positions, the identity and sexual orientation of artists could quite easily influence both their audience and the spaces which their audience inhabits, and having an artist vocally identify with a minority sexuality could normalize the existence of that orientation among their audience.

The lens of sexual orientation and presentation itself, especially in regards to music, also changes drastically based on the space it is present in, even among queer spaces. Queer bar spaces, for example, are led by a sense of erotic sexuality, and their queer aesthetic is thus far more sexualized compared to queer choral music spaces (Miyake, 2013). Queer music spaces being eroticized, even in research, is not very surprising when the fight for rights for all sexualities is one based around the spectrum of expressing sexual attraction. However, queer musical aesthetic extends outside of specifically gay and lesbian musical spaces as well, creating communities that become forces of activism and reminders of community support for queer individuals (Miyake, 2013).

As well as looking at groups of people of certain sexualities to try and discern leanings towards certain genres, it’s possible to look at fans of certain genres and try to discern leanings towards certain sexualities. It’s even possible for the fans themselves to be the ones doing this. Discussion among pop music fans especially leans into queer aesthetic and queer-friendly spaces, generating in-jokes and assumptions that participating members are not heterosexual (r/popheads, 2019). Even participating heterosexual individuals express a fear of being considered more homosexual or less masculine by admitting to participating in the genre. Discussion like this in these spaces also opens up the idea that, instead of actually having a majority population of a certain sexual orientation, individuals are instead scared to speak up if they do not fit the stereotype of the community for fear of being othered and outcast (r/popheads, 2019).

Music, Sexual Orientation, and Correlation

The general consensus of my sources leads towards the idea that music has been highly important to the history of expression and community among queer individuals. Queer individuals who create music have done so from inside the closet, and also by creating their own genres through explicit use of non-heteronormative practices and aesthetics. Genres heavily influenced by queer individuals and aesthetic could still contain higher representation of minority sexualities However, it is just as possible that such histories have not truly shaped the medium to this day, but only created a stereotype of the medium in the eyes of a heteronormative-aligned public. Whether queer spaces in music have persisted to this day or not, their history is important not just to the queer community, but to the whole of music and theatre.

Bibliography

Brett, P. (1977). “Britten and Grimes.” The Musical Times, 118(1618), 995-1000. doi: 10.2307/959289

Brett, P., Wood, E., & Hubbs, N. (2012, July 10). “Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer music.” Grove Music Online. Retrieved 29 Sep. 2019, from https://www-oxfordmusiconline-com.du.idm.oclc.org/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-1002224712.

Joseph Michael Abramo (2011). “Queering informal pedagogy: sexuality and popular music in school.” Music Education Research, 13:4, 465-477, DOI:10.1080/14613808.2011.632084

Miyake, E. (2013, March 3). Understanding Music and Sexuality through Ethnography: Dialogues between Queer Studies and Music. Transposition, (3). doi: 10.4000/transposition.150

r/popheads (2019, August 1) Is there a correlation between sexual orientation and music taste?. Retrieved from https://www.reddit.com/r/popheads/comments/ckmit8/is_there_a_correlation_between_sexual_orientation/.

Waldrip, R. (2017, November 30). We Are What We Listen To: How Music Makes Our Identity. Retrieved from https://www.martechadvisor.com/articles/data-management/we-are-what-we-listen-to-how-music-makes-our-identity/.

Miller, J. (2011). Spectacle and Sexuality: Music, Clothes and Queer Bodies. In Fashion and Music (pp. 131–154). Oxford: Berg. Retrieved October 07 2019, from http://dx.doi.org.du.idm.oclc.org/10.2752/9781472504418/Miller0009

0 notes

Text

Duality

Content warning: I’m going to be talking about life experiences that involve homophobia, transphobia, general bigotry and White Feminism. Though I suppose that last part is redundant.

So my grandmother has been on my mind a lot lately.

We’re getting up to the one year anniversary of her death. She lived to be in her 90s, so it’s not quite a tragedy.

Thing is, the reason I’ve been thinking of her has more to do with the sort of compartmentalized way I think about my family.

See, what started this whole thing was a not-so-pleasant memory. I was in the ballpark of 10 and at my grandparents’ and my brother and I were watching Look Who’s Talking. Complain about our bad taste, but I was 10 and he was 8 and pretty much everyone we knew had seen it. So ostensibly there’s a problem with us watching a PG-13 movie, but we’d watched worse. And my grandmother, walking in and out of the room the whole time, was fine with the content. Until she walked into the room when one of the characters said “lesbian” or some other word that meant lesbian, because I haven’t watched the movie since maybe a couple years after this movie and I don’t really remember. It wasn’t the first time the term had been used, but when my grandmother heard it, she lost her shit.

I honestly don’t think I’ve ever seen her as mad as when her grandkids heard the word lesbian.

My grandmother was a massive homophobe. And not in some mild, esoteric sense, in the sense that even the slightest reference to gay people was completely unhinging. And, in my family, I was encouraged to not fight (this only went one way; one of my aunts had called me a Nazi multiple times for my ‘liberal’ beliefs by the age of 12), so my solution was to avoid the topic. Actually, I tended to avoid anything even remotely political with my family, because they tended to be close to the polar opposite of me. My mom and dad were both hippies who were arrested for standing up for civil rights and held all sorts of commie pinko ideals, so that probably insulated my brother and I, but my mother was also the biggest voice of appeasement in my life.

Over the years, my grandmother would make some offhand comments that fell into transphobia, as well. Thing is, trans individuals weren’t on their radar as much, so I didn’t get as much on that front as their LGB phobia, but I knew it was there. That’s the environment I grew up in.

I was raised to think of my grandmother as a nice, sweet woman. And she had all the appearance of it right up until you talked about that one subject. A subject which probably doesn’t seem so bad to the rest of my family, but impacts me. The rest of my family weren’t quite so extreme, but there’s quite a few homophobes and transphobes kicking around. I remember back when their state voted to not change the state constitution to redefine marriage as between one man and one woman, multiple family members freaked out because “the gays are getting everything they want!”

Note that same-sex couples actually didn’t. Same-sex marriage was not legal in the state, it just hadn’t been rendered further beyond residents’ reach by making it a constitutional proposition. Admittedly, this is important if you’re LGBT, but it’s nowhere near “getting everything we want.”

When same sex marriage finally became legal, I avoided them for months. I’m not supposed to fight, but they will take any opportunity to pounce on me and my ‘liberal’ ways.

This wasn’t too hard, as I’d learned to disconnect from my family. As much as I can think of my family in loving terms despite their bigoted mentality, I think part of the reason I can do that is that I started not being involved with them. My brother and I have radically different relationships with my family, and this is at least a chunk of why, I suspect.

I don’t know if all my family’s like this. I’d think, statistically, there’d have to be some other people in my family treat who weren’t total bigots, but I don’t trust them because the pattern leads towards hating at least LGBT people (my family tends towards feminism--white feminism, anyhow, because women of color and lesbians and anyone else who is not them is insignificant--despite skewing towards Fox News on most other subjects). I have one openly gay family member and any talk about her when she wasn’t present has been horrible. And I wonder if she even knows that that’s the way they talk, because they’re nice to her face. Which is the other issue: even if they came off as nice or loving or tolerant or accepting, how can I ever trust people like this when there’s a known history of them saying one thing to a gay person’s face and another behind her back?

This comes to mind quite often for reasons not directly related to my grandmother, but more to my SO. My family loves Tal. They’re always welcome at Thanksgiving and Christmas, my mom actively asks about them, we’re supposedly an adorable couple, and even the people who only met Tal at my brother’s wedding have had nice things to say.

Except they think Tal’s my girlfriend and we’re in a completely heterosexual relationship. And I’m pretty sure there’s no combination of the two of us that translates to a straight couple. So really, they don’t necessarily love us, but the idea of us in their mind.

It seems like this is part of a larger trend. The “conservative uncle” is a cliche for a reason. But--and I’m likely surprising nobody here--it’s really difficult to reconcile the concept of “is a good person” with the concept of “hates people like you, perhaps violently.”

I can superficially hold the idea of my grandmother or my aunt or whoever as a good person, but when I think on it, I no longer can. These people are full of hate. Even if they didn’t hate me (or my SO) specifically, they have a blanket hatred of people like me (and my SO).

At the same time, because I am presumed straight and cis (and on both counts, I swear it’s because they are determined to see it), I’ve seen exactly how they conduct themselves towards gay family members, so even if they’re totally awesome to my face, I don’t know that I can ever trust that reaction as genuine.

Kind of makes me wonder how many other LGBT family members I might have who are similarly disposed to not want to deal with this crap.

When my grandmother died, part of me was relieved. She was the most vitriolic homophobe in my family. At least, she was the most openly homophobic. It’s hard to really tell when so many homophobes are “not homophobic, but....”

Even still, I feel bad. I live in a culture where we’re told to appease the bigots, that it’s just an alternate opinion. I mean, you can’t hate someone for an alternate opinion, right? Hate is wrong. Except, you know, somehow for the people who are actually hating. I grew up in a family where I was not to get “political” while existing as someone whose life is automatically considered political. And where family means loving someone who hates you, someone who would deny you rights, or even someone who would do you harm.

This is my normal. This is the family I grew up with, the only reality I knew. People who expect love and support unconditionally while spewing bigoted crap and putting conditions on their own reality. And that’s still entrenched in my mind, decades later. So I end up feeling bad for having hostile reactions to people who, even if they don’t hate me specifically, hate people like me.

That’s not a good place to be.

Ironically, my grandmother was easiest to deal with, because at least I knew where she stood. On the other end of that spectrum remains my mother. I have doubts as to whether or not she’d support her trans daughter, but somewhat worse in my mind is that she has spent decades playing that “apolitical” appeasement card. Sitting back while her family (and my father’s, to some extent) go on the attack and encouraging the other party to be quiet.

“It takes two to tango,” the logic goes. Unfortunately, years of dodging my family’s barbs demonstrates this is complete and utter garbage. It just encourages them to continue attacking. Because they went unopposed, they got the idea that their conduct was acceptable.

These are the people I’m supposed to love, and it’s my fault if I let pesky things like hate get in the way.

So I generally don’t deal with them. Since I don’t know who’s actually a bigot under the surface, I tend to not engage any of them. I literally can’t trust these people, and that’s the funny thing:

They raised me this way. I am as they made me.

But it goes beyond that, because there’s this idea that ‘if you can’t trust family, who can you trust?’ and since I can’t trust family, well, who can I trust? I feel borderline paranoid, but I have very good reasons to not trust people and it starts at home. Granted, I’ve got a long history of people demonstrating they’re not trustworthy outside of my home life, but I had a solid foundation before I really started dealing with the outside world.

This rambled to places I hadn’t particularly intended. I’ll just end this by saying that the longer I deal with this, the more untenable, toxic, and simply intolerable it is. I very much resent the way the feelings of bigots are sacrosanct at the expense of...well, in this case, me. But in general, too.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lit Review Draft 1

What Is the Correlation Between Sexuality and Music Taste?

Sexuality, Presentation, and Music

Presentation and aesthetic is regarded as an important aspect of belonging within groups, and the perception of sexuality groups is no different in this regard. Certain behaviors, appearances, names, voices, and more are frequently considered to belong to specific genders or sexualities, no matter how true that assumption may actually be. While these assumptions may affect the groups that gravitate towards these aspects of personal presentation, they definitely affect which groups gravitate away. Young, straight men seem to easily fall into this avoidant group, especially in situations where they believe they are being judged by male peers (Abramo, 2011). Abramo’s observations with high-school aged boys seemed to show an assumption among young straight men that having certain presentations in music, like using the head voice or singing softer lyrics, imply damaged or abnormal masculinity, and cause them to become defensive to avoid the ridicule of being assumed as not heteronormative.

On the opposite end of aesthetic, many music artists intentionally evoke queer presentation as a method of performance, whether they are queer or not. Artists like The Scissor Sisters utilize the colorful, purposefully overblown aesthetic of camp to express queer narratives and experiences through both their music and their bodies. Rappers like Jwl B reveal their entire body on stage, and through doing so show the real form of queer bodies, not the idealized and pornographic images of performers often edited or circulated beyond the control of the original person. Especially for non-straight performers, taking charge of their own bodies and aesthetic and pushing them away from heteronormative expectations is an important part of the declaration of the unique queer experience (Miller, 2011).