#Argentine literature

Text

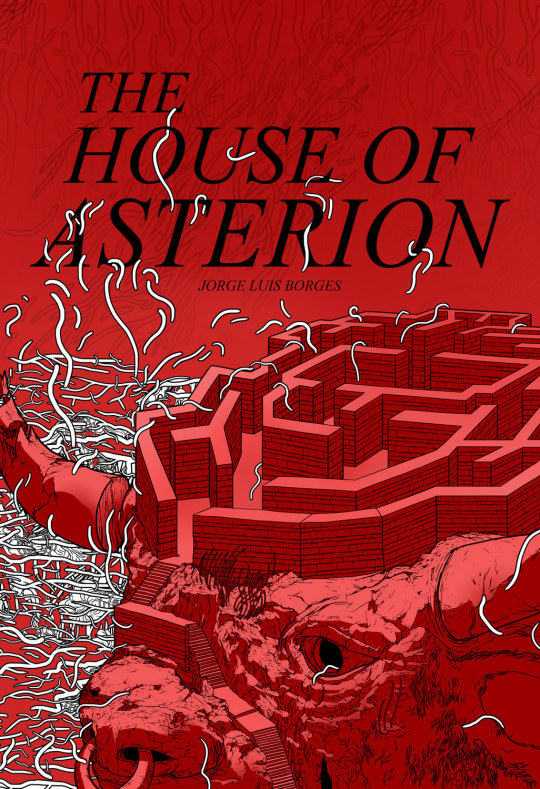

*Originally published in Spanish under the title "La casa de Asterion"

#short stories#short story#the house of asterion#la casa de asterion#jorge luis borges#20th century literature#spanish language literature#argentine literature#have you read this short fiction?#book polls#completed polls

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Time is the substance I am made of. Time is a river which sweeps me along, but I am the river; it is a tiger which destroys me, but I am the tiger; it is a fire which consumes me, but I am the fire.

Jorge Luis Borges, Labyrinths: Selected Stories & Other Writings, 1962

#jorge luis borges#labyrinths#destruction#argentine literature#selected stories#literary text#quotes#dark acadamia aesthetic#classic literature#translated literature

111 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I wrote my thesis on some of the short stories in Ficciones by Jorge Luis Borges, translated by Andrew Hurley, but it's now been a few years since I read them. So I was due for a reread. And what better time to read Borges than while in Buenos Aires, his own beloved city, his own world of labyrinthine streets and old bookshops?

I read Ficciones while walking through los bosques de Palermo. I read it over a submarino on a just-ok day in El Calafate. And I finished it on an estancia, surrounded by mountains and beautiful horses and twisting paths.

These short stories never stop hitting. You never quite lose your thesis, and even rereading them now, I kept getting ideas. If I ever go back to grad school, I could go straight back to Borges and his ideas about creation and reading and what it means to try and put something out into the world. I love his twisty wild brain, and it was so cool to dig back into it in Argentina.

#ficciones#jorge luis borges#books in translation#translated literature#argentine literature#reading while wandering argentina#my book reviews#reread

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Galloping Hour, Flora Alejandra Pizarnik

[ID: Fear of being two path of the mirror.]

#flora alejandra pizarnik#alejandra pizarnik#literature#bibliophile#poetry#mirror#poem#quotes#the galloping hour#argentine poetry#argentine literature

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

— Alejandra Pizarnik, from “Diarios.”

#alejandra pizarnik#diarios#escritos diarios#literatura argentina#argentine literature#poems#poemas#poesía#poetry#literatura#soledad#frases#literature

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Un buen escritor no es cuentista ni novelista: es una persona resignada que escribe lo que puede. También aprendí que los géneros literarios son una ilusión. Imaginamos historias, y lo único que podemos hacer es atacar su forma, que siempre es anterior a las palabras, aceptar sus leyes y tratar de no equivocarnos demasiado.

- Abelardo Castillo, Las maquinarias de la noche. Los mundos reales IV. Prólogo. Pág. 10.

#abelardo castillo#las maquinarias de la noche#literatura argentina#argentine literature#short stories#cuentos#escritores argentinos#escritores

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Dangers of Smoking in Bed by Mariana Enriquez

Book 19/50 of 2022

Date Finished: 1st March 2022

Rating: 5/5

#literature#books#reading#horror#horror books#horror fiction#argentine literature#mariana enriquez#the dangers of smoking in bed#bookblr#bookworm

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Prank phone calls were known as cachadas and they were as old as the invention of the phone itself. We had a wide array of tactics, all aimed at annoying an unsuspecting interlocutor; pissing them off, riling them up. Somewhere around the middle of high school Chiri and I became experts in the art. We were telephone magicians. But then a sad event forced us to abandon our calling. To this day, the story is a reminder of the evil that resides within us.

We began, like everyone does, as children. When telephones were black, rotary, and state-issued. The first infantile prank calls are always made to someone with the last name Gallo, (no one knows why, but that’s the way it is). In the Mercedes municipal phone book there were nine listings under Gallo, which means rooster in Spanish. We called them one by one.

“Hello, the Gallos?”

“Yes,” they said on the other end.

“Is Remigio there?”

“There’s no Remigio here.”

“Sorry, I guess I have the wrong henhouse,” and we hung up, dying of laughter.

There are dozens of these basic jokes, and we copied our older siblings or cousins, who had already moved on to more elaborate pranks. As you can see, the main objective of our first incursions into the art of the prank call was laughter: a clean cackle that didn’t cause any major harm to the victim.

Oh, if only we could’ve remained in our childhood innocence, free from evil and guilt. But no: we have to mature. And mature we did.

There are always rumors circulating in small towns, facts and details about neighbors who are easy targets for prank calls. Neighbors considered “prickly.” It was generally a certain type of old man who, when he received a prank call, would unleash the full force of his fury and seemed incapable of hanging up the phone. Around age ten or twelve, we got a reliable tip: you have to call Mr. Toledo and say the magic word.

“Hello, is this the Toledo residence?”

“Yes.”

“Is ‘Trumpeter’ there?”

This was the word that triggered Mr. Toledo, who had a high-pitched, strident voice like a horn, to begin his steam of insults and curses, punctuated with hilarious huffs and wild neologisms. Chiri and I would crowd around the receiver and imagine Toledo at his house, in his underwear, his cheeks a deep red color and smoke shooting out of his ears. Ten minutes in, when his diatribe began to lose steam and his lungs to lose air, all we had to say was “don’t get so worked up, Trumpeter,” and he’d start all over again. Mission accomplished.

But a boy must grow, and with him, ambition, dramatic structure, and a still-dormant evil begins to take shape. It wasn’t long before Chiri and I became bored with invisible Gallos and Toledos, who were merely disembodied voices on the other end of the line, so we moved into the realm of three-dimensional pranks, with live victims.

Every afternoon the bald man who ran the shop across the street would close up for the day and head home following hours of total boredom without having sold anything. We could see him, resigned, from the dining room window. Right when the bald guy lowered the heavy metal shutter over his storefront, just before he wrapped the chain around the latch, we called him on the phone. The poor man, who didn’t want to lose a sale, desperately raised the shutter, ran to the back of the shop and, on the fifth or sixth ring, panted: “Pontoni Carpets, good afternoon.”

And we hung up.

A little while later we’d see him once again, humiliated and defeated, lowering his gigantic shutter; it was twice as heavy this time. His life was shit, you could see it in his eyes and in the curve of his spine. Then the bald man once again heard the phone ring inside the shop. “If it’s the same person who called before, they must need carpeting urgently,” the shopkeeper thought, and once again his heart pounded, and once again he raised the shutter, once again he ran to the back of the shop, and once again he said, “Pontoni Carpets, good evening,” with a thread of a voice.

We hung up. We always hung up.

One day we repeated the trick so many times that on the umpteenth fake call the bald man had no other recourse than to say, “Pontoni Carpets, good evening.”

We would’ve gone on like that until the end of time, but a year later we crashed headlong into the future. One day, on the first ring, old bald Pontoni pulled out a brick with an antennae on it and said “Hello.” He’d bought a cordless phone.

Far from deterring us, the advent of technology afforded new opportunities. When we got a second phone at my house (one with a cord, one without) Chiri and I invented something we called telecomedy. This type of prank involved two voices and a passive receptor. It consisted of calling any random number and making the victim believe they were interrupting a private conversation.

VICTIM: “Hello?”

CHIRI (in a woman’s voice): “. . . you like it when I do that.”

VICTIM: “Excuse me?”

HERNÁN (in a man’s voice): “What I like is to lick your ass.”

CHIRI: “Mmmm, don’t say that, you’re getting my nipples all hard.”

VICTIM: “Who is this?”

HERNÁN: “What’s getting hard is my cock,” et cetera.

The objective of this dramatic exercise was to get the interlocutor to stop saying “hello” and start listening to our obscene conversation, like someone hidden underneath a hotel bed. The better our stories, the longer the victim took to get bored and hang up. It was, I suppose, great practice in plotting, which would serve us—in the future—to keep our readers hooked. One day, after ten minutes of telecomedy, one of our victims started panting, and it grossed us out.

By age sixteen or seventeen, we considered ourselves radio theater professionals. We’d learned presence and emotional expression, and had developed a natural reflex for improvisation. Chiri and I skipped our afternoon gym class to shut ourselves up at home with two or three telephones, a little Sanyo recorder, and some props that could make sounds like rain, traffic, fire, or blizzard. We also had egg whites on hand, in case we wanted to change the pitch of our voices.

We didn’t need to talk to each other: we communicated solely through gestures and glances, like radio announcers behind the glass. We worked magic. We could send a stranger down to City Hall to pick up a non-existent tax bill, seduce the receptionist at a doctor’s office, make a firetruck siren sound whenever we felt like it, and convince the owner of the kiosk on the corner of 19th and 30th that he was speaking to us live on-air from a radio station in Luján.

We thought we were gods, and perhaps this hubris is what caused us to fall so quickly from the zenith of our glory and hit rock bottom.

It was the middle of 1988. I remember because we were wearing digital watches to time ourselves. It was dark and my parents weren’t home. For hours, Chiri and I had been playing an enthralling game: make the victim stay on the line as long as possible at all costs. When you become a professional prank caller you go back to the basics. The game consisted of calling a random number and pulling a conversation out of thin air. The clock started at “hello” and ran until the click of the hang up.

That night Chiri had put on a perfect performance: he’d maintained a conversation for seventeen minutes twelve seconds with an old lady, telling her he was calling from the dry cleaner’s. They’d had a hilarious exchange about ironing and drying and ended up singing a duet of “Nostalgias” together. Chiri had the woman wrapped around his little finger, with masterful winks and touches of genius. It would be impossible to outdo him.

I rolled the dice. I got 24612. I dialed the number. Chiri had the stopwatch in his hand and he looked smug. When the voice of an old lady said “Hello” the seconds began to tick away.

I had developed a system—my house brand if you will—that I could pull out at any critical moment. It was a risky strategy that involved using a standard male voice, a monotonous, slow voice, and urging the victim to guess my identity. That night, in what would be the last prank call of my life, I used this technique.

“Who is it?” the old lady asked after my “hello.”

“Oh great,” I said. “You don’t even recognize my voice?”

This was a king’s pawn game. A classic opening. It generated a feeling of familiarity in the other. There’s always some grown nephew whose voice has changed, or a godson. Always.

“I don’t know,” said the old lady. “Who are you trying to call?”

“You, you old bag!”

Super risky move. I was placing the queen in the center of the board. Very few people would call a lady “an old bag.” But if I wanted to beat Chiri’s time, I had to behave like a kamikaze. It worked:

“Daniel?!” she said, in that tone halfway between a question and an exclamation. The tone is called “wishful thinking.”

The way she pronounced that name gave me a million clues. Daniel wasn’t a nephew or a godson, because the old lady’s scream had been deafening. It could be no less than a son. Possibly an only son. And that same piece of evidence led me to another conclusion: the son lived far away and he didn’t call his mother often. I dove in headfirst.

“Of course, Mom! Who else would it be?”

“Danny, little Dan!” the old woman sobbed, as Chiri silently took an imaginary hat off of his head, surrendering to my move.

Now, time was on my side. I paced around with the cordless so that Chiri couldn’t try to make me laugh. He sat listening in on the regular phone. After five minutes I’d learned that Daniel lived in the South (“is it cold down there?” the old lady asked in the middle of September), and also that in recent years the relationship between them hadn’t been very warm.

“Dad would’ve liked you to be at his funeral.”

“It’s not easy, Mom. There are open wounds, life isn’t that simple.”

I learned that Daniel had a wife—Negra—and two kids. The youngest, Carlitos, had never met his grandmother. I also learned that the city Daniel lived in was Comodoro Rivadavia, and that he worked in a television factory. At twelve minutes into the conversation, when I was on track to beat Chiri’s record, the old lady began to suspect something was up. She started asking ambiguous questions, I had to improvise.

“How is it that you sound so close, son?” she wanted to know.

She left me with no choice. “Mom,” I said, surprised by my cruelty. “I’m here, at the station.”

Silence from the other end of the line, and then a muffled sob. I turned around and made eye contact with Chiri, who was staring at me, his face pale. He wasn’t smiling. I felt, from deep inside, the pull of evil. I felt it for the first time in my life. It came from my stomach, my cock, and my brain all at the same time, like a diabolical holy trinity. With a gesture, I asked Chiri how long I’d been talking. Sixteen minutes.

“Don’t cry, Ma,” I said.

“Have you come to Mercedes before?” she asked in a broken voice. “Sometimes I dream that you come, at night, and you don’t stop by the house . . .”

“No. No, no . . . It’s the first time I’ve been back, I swear. But I didn’t want to just show up, out of nowhere. That’s why I called.”

“Son!” she shouted, heartbroken. “Hang up and hurry over, come home!”

Almost seventeen minutes, I needed something else. I clenched my left fist as I decided what to say. I think the evil had taken full control of me by that point. I don’t think I was even the one speaking. Something indefinable, the thing that makes us human and horrible, was now rooted deep within me and I was its puppet.

“I have to do a few things first, then I’ll come home,” I said. “Listen, Mom. Will you make cannelloni? I’m starving.”

“Of course, Danny.”

“I miss your cannelloni.”

“Hurry up, I’ll make them now.”

“Bye.”

“Bye, son. I’m trembling all over, hurry up.”

And the woman hung up the phone.

I looked at Chiri, who was staring down at the floor. He refused to make eye contact, I guess he couldn’t look me in the face. He didn’t remember to stop the clock, so we never even found out who won. We sat on the couch for a while, not saying a word. Half an hour later we knew that somewhere in Mercedes there was a house, and in that house there was a table, and on that table sat a steaming dish.

And we knew that our childhood would be over the moment Daniel’s cannelloni grew cold.

- Cannelloni by Hernán Casciari. 19 april, 2007

#short story#literature#latin american literature#latin american authors#cannelloni#canelones#argentina#argentine literature#hernan casciari#coming of age#family drama#prank calls#pranks#fiction

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cats were heavily featured in Fini's art, and she had 50 cats throughout her life. #ShowMeYourKitties

#leonor fini#lgbt#biseuxal#bisexuality#lgbtqia#lgbtq#queer#representation matters#bi visibility#bi pride#argentina#argentine literature#bi artists#painting#surrealism#bi#argentinian art#feminist#feminism#nonconformist#painter

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I slip into the trap of geometry, that method we Occidentals use to try to regulate our lives: axis, center, raison d'être, Omphalos, nostalgic Indo-European names. Even this existence I sometimes try to describe, this Paris where I move about like a dry leaf, would not be visible if behind it there did not beat an anxiety for an axis, a coming together with the center shaft. All these words, all these terms for the same disorder. Sometimes I am convinced that triangle is another name for stupidity, that eight times eight is madness or a dog.

Hopscotch, Julio Cortázar (transl. Gregory Rabassa 1966)

#interesting novel so far#though I feel a bit too dumb for it#julio cortázar#Argentine literature#hispanic literature

1 note

·

View note

Text

The idea of the absence of meaning

“… There are times I feel that nothing has meaning. On a tiny planet that has been racing toward oblivion for millions of years, we are born amid sorrow; we grow, we struggle, we grow ill, we suffer, we make others suffer, we cry out, we die, others die, and new beings are born to begin the senseless comedy all over again.”

Was that really it? I sat pondering the idea of the absence of meaning. Was our life nothing more than a sequence of anonymous screams in a desert of indifferent stars?

ERNESTO SÁBATO

Excerpt from The Tunnel. Penguin Classics, 2012. Translated from the Spanish by Margaret Sayers Peden.

0 notes

Text

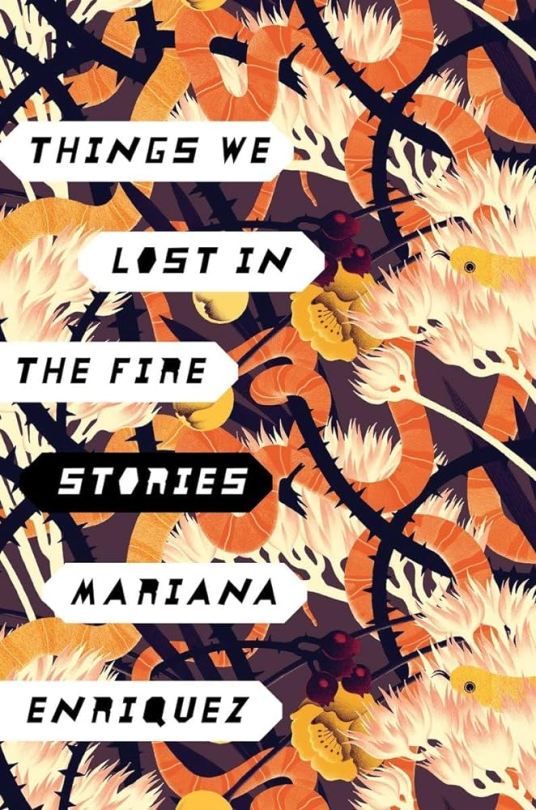

*Originally published in Spanish under the title "Las cosas que perdimos en el fuego"

#short story collection#short story collections#mariana enríquez#things we lost in the fire#things we lost in the fire: stories#las cosas que perdimos en el fuego#argentine literature#argentinian literature#spanish language literature#21st century literature#have you read this short fiction?#book polls#completed polls

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Suicide

Not a single star will be left in the night.

The night will not be left.

I will die and, with me,

the weight of the intolerable universe.

I shall erase the pyramids, the medallions,

the continents and faces.

I shall erase the accumulated past.

I shall make dust of history, dust of dust.

Now I am looking on the final sunset.

I am hearing the last bird.

I bequeath nothingness to no one.

Jorge Luis Borges, from Selected Poems, 1971

#jorge luis borges#selected poems#suicide#argentine literature#classic poetry#translated literature#quotes#dark acadamia aesthetic#translated poetry

14 notes

·

View notes

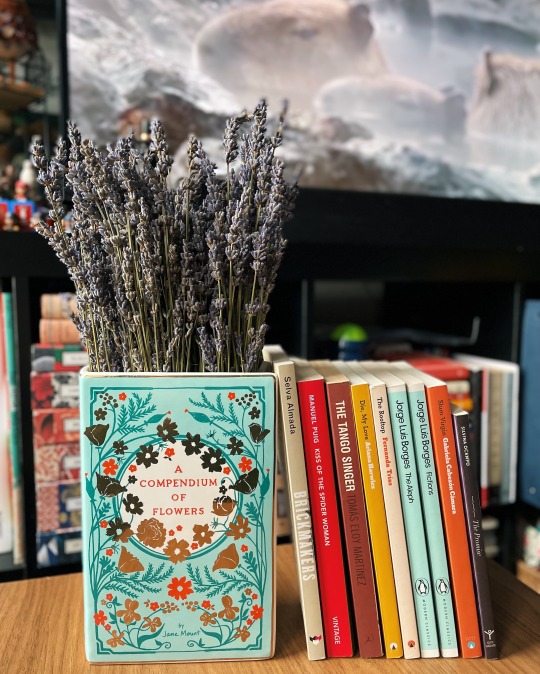

Photo

I bring a lot of books with me on vacation. Traveling solo brings a lot more downtime than when you travel with someone. My trip to Argentina includes a few plane rides (including the two big ones). My itinerary includes spending relaxing afternoons at pretty cafés or in stunning bookstores. And of course, nights or mornings in lovely airbnbs, enjoying coffee or a drink. A huge part of being able to travel solo is being able to have books as my companions.

I read a book every 2.5 days, and I will be away from home for 18 days—so mathematically, I need at least 7 books (yes, I do know ereaders exist, they’re just not for me). Once upon a time, any books would do. But now, I think quite a bit about which books to bring. My book stack for Argentina is all Argentinian, except for one Uruguayan author (I’ll be in Colonia de Sacramento as a day trip), and one author of a book about getting lost, which I fittingly forgot to include in this photo.

The list:

Brickmakers by Selva Almada, tr. Annie McDermott

Kiss of the Spider Woman by Manuel Puig, tr. Thomas Colchie

The Tango Singer by Tomás Eloy Martínez, tr. Anne McLean

Die, My Love by Ariana Harwicz, tr. Sarah Moses & Carolina Orloff

The Rooftop by Fernanda Trías, tr. Annie McDermott

Fictions and The Aleph by Jorge Luis Borges, tr. Andrew Hurley

Slum Virgin by Gabriela Cabezón Cámara, tr. Frances Riddle

The Promise by Silvina Ocampo, tr. Suzanne Jill Levine & Jessica Powell

I’m particularly looking forward to reading Borges, one of my favorite authors, in the winding streets of his city, and to read another book by Cámara. Good book-friends of mine might wonder why Mariana Enríquez isn’t on my reading list. The answer is simple: I’m not looking to freak myself out while reading late at night in a quiet, blustery Patagonian town...

#argentine literature#argentinian literature#selva almada#jorge luis borges#silvina ocampo#book stack#reading while wandering#reading while wandering argentina

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Y el pueblo se vació...

como si la madera viva hubiera sido el tapón que lo mantenía lleno." - El Bosque del Primer Piso

0 notes

Text

9 de Julio, día de la Independencia Argentina

#argentine tango#dario argento#rock argentino#argentina#cine argentino#digital illustration#digital art#digital fanart#cats#digital drawing#drawing#argentinian literature#kitties#sketches#doodle#sketch#traditional art#meme#funny memes#new memes

16 notes

·

View notes