#Arnie Zane

Text

Footnote 47 in “My Government Means to Kill Me” spotlights a pair of gay forerunners that I admire with all my heart: dance legends and lovers Bill T. Jones and Arnie Zane.

#gay books#mygovernmentmeanstokillme#queer books#lgbtq books#booksbooksbooks#footnotes#black books#gay fiction#historical fiction#Bill T. Jones#Arnie Zane

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

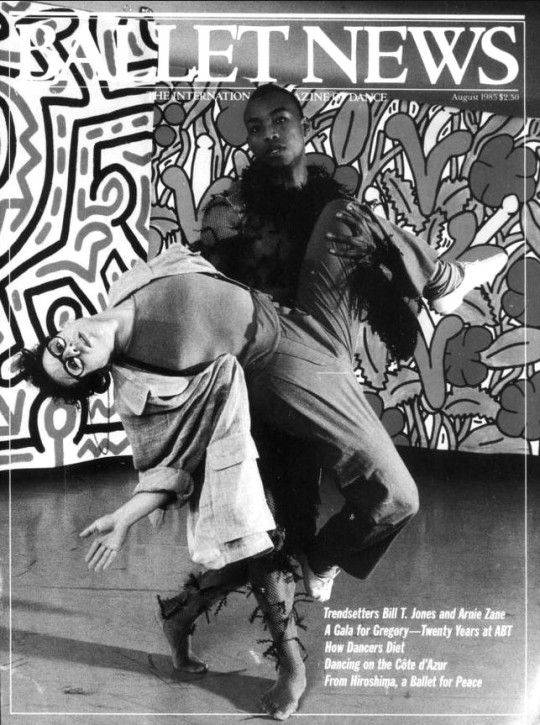

Post-Modernist dancers Bill T. Jones and Arnie Zane with a backdrop by Keith Haring on the cover of Ballet News, August 1985.

#bill t. jones#arnie zane#dance#dancers#male dancers#post-modernism#keith haring#ballet news#magazine covers#80s#lgbtq#lgbtq history#went down a rabbit hole today. they were partners in business and in life until arnie passed in 1988 but their dance company is still going#strong under jones' direction. jones is an absolutely magnetic speaker there are vids on yt where he talks about his thought process#for his choreographies and also different interviews and talking about arnie and he's just so well spoken his every word carries weight#he seems a genuine and profound human being

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Artist Alex Katz created this mural, Bill 2, a portrait of modern dancer and choreographer Bill T. Jones, in 2019 for Murals of La Jolla in San Diego. Murals of La Jolla is a project started in 2010 by The Athenaeum and the La Jolla Community Foundation. It commissions artists to create work to be displayed on buildings around La Jolla. A map of all the murals currently on view can be found here.

From the Murals of La Jolla website about the work-

Alex Katz’s mural, Bill 2, celebrates Bill T. Jones, one of the most noted and recognized modern-dance choreographers of our time. Executed in Katz’s bold and simplified signature style, Bill 2 depicts Jones’ visage, through a series of distinct expressions. The repetition of his face has a cinematic and lyrical quality, reinforcing his place in the world of dance, music and film. Portions of the face are dramatically cropped, giving the viewer only quick and gestural glimpses of Jones. Bill 2, is a striking homage to two artists, Katz and Jones, both renowned in their respective fields of visual and performing arts. The mural’s proximity to the new Conrad Prebys Performing Arts Center gives a nod to the interconnected worlds of art, music, and dance.

The Guggenheim museum in NYC is currently showing Alex Katz: Gathering, a retrospective of the artist’s work from the late 1940’s until the present. The exhibition will be up until February 20, 2023.

From their website about the exhibition-

Emerging as an artist in the mid-20th century, Katz forged a mode of figurative painting that fused the energy of Abstract Expressionist canvases with the American vernaculars of the magazine, billboard, and movie screen. Throughout his practice, he has turned to his surroundings in downtown New York City and coastal Maine as his primary subject matter, documenting an evolving community of poets, artists, critics, dancers, and filmmakers who have animated the cultural avant-garde from the postwar period to the present.

Staged in the city where Katz has lived and worked his entire life, and prepared with the close collaboration of the artist, this retrospective will fill the museum’s Frank Lloyd Wright rotunda. Encompassing paintings, oil sketches, collages, drawings, prints, and freestanding “cutout” works, the exhibition will begin with the artist’s intimate sketches of riders on the New York City subway from the late 1940s and will culminate in the rapturous, immersive landscapes that have dominated his output in recent years.

Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Company has numerous performances every year. Conceived and directed by Bill T. Jones, and choreographed by Jones with Janet Wong and the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Company, the latest work, Curriculum II, will be performed at on March 10, 11, and 12, at the Institute of Contemporary Art Boston.

Jones also hosts the series Bill Chats at NYC’s The New School. On January 30th, he will be in conversation with Bessie Award-winning theater director and performance artist, Niegel Smith and curator, producer, and director, Kamilah Forbes. For more events check out the New York Live Arts calendar.

#alex katz#murals of la jolla#bill t. jones#guggenheim museum#painting#la jolla#san diego murals#california murals#artist portrait#street art#murals#san diego street art#dance performance#nyc art shows#art shows#bill t jones arnie zane company#artist talks#the new school#ica boston

7 notes

·

View notes

Video

0 notes

Text

Angélique Kidjo, Bill T. Jones & Thelonius Monk Documentaries Are Scheduled For Season 15 Of AfroPoP: The Ultimate Cultural Exchange

Documentaries about African singer Angélique Kidjo, choreographer Bill T. Jones and jazz musician Thelonious Monk are scheduled for season 15 of AfroPoP: The Ultimate Cultural Exchange. The new season is different from previous ones because it focuses on one theme by singling out Black art for the first time. The WORLD Channel has been the home and co-producer of the show with Black Public Media since 2010. Leslie Fields-Cruz, BPM executive director and AfroPoP executive producer had this to say about their 15th anniversary:

“When we created AfroPoP: The Ultimate Cultural Exchange it was our hope that we would be able to bring stories of modern Black life to public media audiences and help augment viewers’ ideas of what Black life is and can be,” said Leslie Fields-Cruz, BPM executive director and AfroPoP executive producer. “Witnessing the series reach its 15th season, a landmark that is the result of the work and drive of so many people over the years, is an awe-inspiring and humbling moment that fills me with great gratitude.”

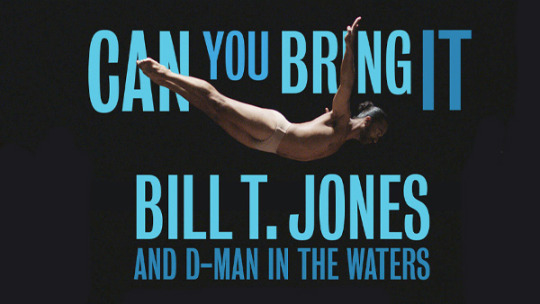

The premiere of Can You Bring It: Bill T. Jones and D-Man In The Waters will stream exclusively on Black Public Media's YouTube Channel at midnight ET on Monday, April 3rd. The film will screen later on that day at 8 PM ET on WORLD Channel. The feature looks at the ballet D-Man In The Waters originally presented in 1989 by Jones and his late partner Arnie Zane. The ballet was created in response to the A.I.D.S. crisis at the time and its impact on their dance company and friends.

Claire Duguet's Queen Kidjo will screen on April 10th. The film follows Kidjo's beginnings in Benin and her rise to legendary status. Bill Traylor: Chasing Ghosts is a portrait of the painter Bill Traylor who was born a slave and started painting scenes of his life on a plantation and the changing urban world at age 85. Jeffrey Wolf's film about Traylor is scheduled for April 17th. The Sound Of Masks is about a Mapiko dancer from Mozambique. The Mapiko dance is exclusively performed by male members of the Makonde community as a tool of independence to defy the colonizing influence of the Mozambican War Of Independence. Sara CF de Gouveia's feature about Mapiko is scheduled to be seen on April 24th. Rewind & Play is Alain Gomis's exhibit of the disrespect jazz pianist and composer Thelonius Monk experienced in 1969 during an appearance on French state television. Rewind & Play will air on May 1st. AfroPoP has been presenting

AfroPoP: The Ultimate Cultural Exchangecan also be viewed on WORLD Channel’s YouTube channel and on all station-branded PBS platforms, including PBS.org and the PBS Video app. The program is available on iOS, Android, Roku streaming devices, Apple TV, Android TV, Amazon Fire TV, Samsung Smart TV, Chromecast and VIZIO. APT will release the season to public television stations across the country on Monday, May 1. For viewing information, check local listings.

youtube

youtube

youtube

youtube

youtube

#afropop: the ultimate cultural exchange#bill traylor#angelique kidjo#thelonius monk#black public media#mapiko#Youtube

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dancer: Barrington Hinds | Company: Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

The DM article is the first time I heard Arnie’s son is in BK: is it confirmed?

Tech the paps in general confirmed it was him, first JJ; so yeah Patrick seems to be in it in a v small role (if not yet updated on IMDb). From the vid what it looks like is he plays someone billy is directing and I think Alex (Charlie’s character) is on set with Billy as he directs the scene.

There are other random people in this film: Rick Ross, Diplo, Billy Zane.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Filmmakers ask "CAN YOU BRING IT?" in powerful new Dance Documentary

"Can You Bring It: Bill T. Jones and D-Man in the Waters" dives deeply into the creative process that culminated in choreographer-dancer-director Bill T. Jones’s tour de force ballet D-Man in the Waters. Born amidst the AIDS crisis in 1989, the production gave physical manifestation to the fear, anger, grief and, ultimately, hope for salvation that the emerging Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Company (both business and life partners at the time) felt individually and as one.

The documentary spotlights a troupe of young dancers in the present day striving to re-interpret the work. In so doing, they collectively explore what is at stake in their own lives to fully commit to and perform the dance successfully. Utilizing an extraordinary collage of interviews, archival material, and uniquely powerful cinematography this lyrical documentary uses the story of an iconic dance to illuminate the power of art and the triumph of the human spirit.

https://youtu.be/zvdqTFNCUwc

Filmmakers ask "CAN YOU BRING IT?" in powerful new Dance Documentary

Co-Director Interviews

with John Smistad

"Can You Bring It: Bill T. Jones and D-Man in the Waters" is about a lot of things.

Dance. Art. Grace. Loss. Devastation. Mourning. Resilience. Strength. Hope.

At it's very core, however, what this remarkable documentary is really about is the limitless power of The Human Spirt. A power that we are all Blessed with. An innate power that, too often it seems, we forget we have.

"Can You Bring It: Bill T. Jones and D-Man in the Waters" serves to remind us of our power.

In a way that can't be forgotten.

I recently interviewed the film's co-directors, Roz LeBlanc and Tom Hurwitz, for my YouTube Channel.

Here's our conversation:

https://youtu.be/d7aTzPUJ--I

"Can You Bring It: Bill T. Jones and D-Man in the Waters" begins streaming on April 3 exclusively on WORLDChannel.org, Black Public Media’s YouTube Channel and on the WORLD YouTube Channel (youtube.com/@worldchannel).

The film will make its national television premiere on WORLD Channel. Check local listings for your WORLD Channel station.

You can enjoy my all of my indie entertainment interviews PLUS film reviews on my YouTube Channel at this link:

JOHN SMISTAD ("TQFC") Film Reviews & Interviews - YouTube

Read the full article

0 notes

Photo

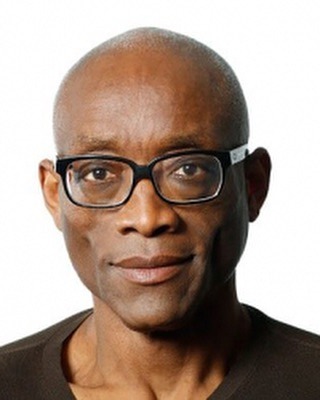

Bill T. Jones (born February 15, 1952) is a choreographer, director, author, and dancer. He is the co-founder of the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company. He is the Artistic Director of New York Live Arts, whose activities encompass an annual presenting season together with allied education programming and services for artists. Independently of New York Live Arts and his dance company, he has choreographed for major performing arts ensembles, contributed to Broadway and other theatrical productions, and collaborated on projects with a range of fellow artists. He has been called "one of the most notable, recognized modern-dance choreographers and directors of our time." He began to attend Binghamton University, and at Binghamton, he shifted his focus to dance. In an interview, he noted: "[Binghamton] was where I first took classes in west African and African-Caribbean dancing. Soon I started skipping track practice to go to those classes. It immediately appealed to me. It was an environment that was not about competition." His dance studies at Binghamton encompassed ballet and modern dance. He and his partner, Arnie Zane, toured the world dancing sexually provocative duets. He had danced solos. The pair formed the Bill T. Jones / Arnie Zane Dance Company, recruiting a troupe of individualistic and nontraditional performers who represented different body sizes, shapes, and colors.” “Jones, a choreographic provocateur, presents his ideas about identity, art, race, sexuality, nudity, power, censorship, homophobia, and AIDS-as-chemical-warfare with a streetwise, in-your-face attitude.” Works such as Last Supper at Uncle Tom’s Cabin/The Promised Land and Still/Here are some of his most thought-provoking works. He has choreographed more than 120 documented works. June 2019, to mark the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall riots, an event widely considered a watershed moment in the modern LGBTQ rights movement, Queerty named him one of the Pride50 "trailblazing individuals who ensure society remains moving towards equality, acceptance, and dignity for all queer people". He is married to Bjorn Amelan, a French national. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence https://www.instagram.com/p/Corr4lfLwBV/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Photo

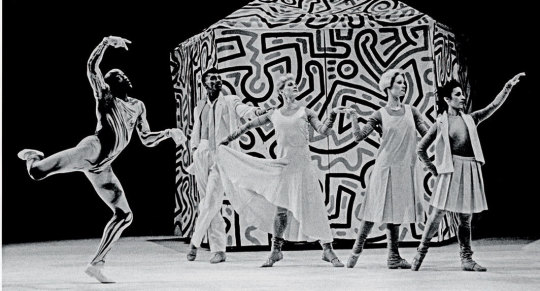

Dancers wearing costumes by Willi Smith in Bill T. Jones and Arnie Zane’s 1984 Secret Pastures, with Keith Haring’s set design in the background, Brooklyn Academy of Music, New York, November 1984. Photo: Tom Caravaglia

via artforum

#keith haring#willi smith#bill t jones#brooklyn#arnie zane#tom caravaglia#set design#black and white#dance

1 note

·

View note

Text

Whoa. Major article on the life of dancer/philosopher king Bill T. Jones.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

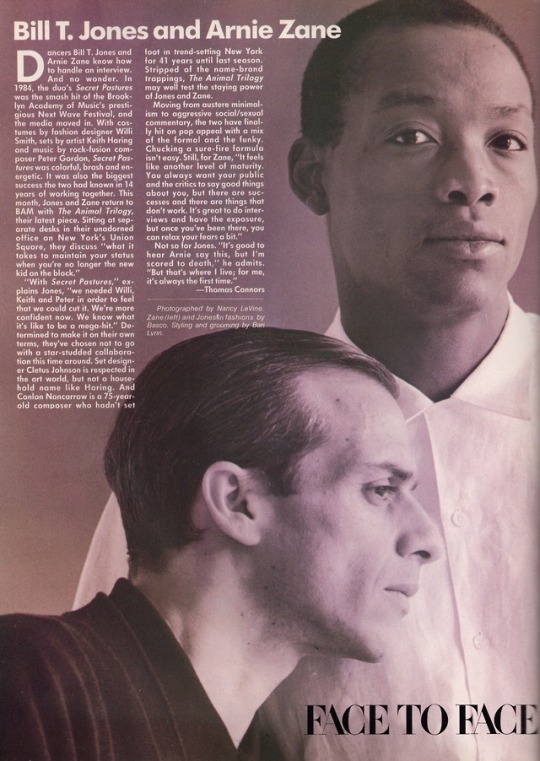

Bill T. Jones and Arnie Zane shot by Nancy LeVine for InFashion 1987

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Vinson Fraley, Jr. of the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Company for Harper’s Bazaar

Photo by Amy Troost

28 notes

·

View notes

Link

Article: The Unbearable Whiteness of Ballet

Date: April 22, 2021

By: Chloe Angyal

In an exclusive excerpt from her new book Turning Pointe, contributing editor Chloe Angyal lays out the ways that white supremacy is embedded in ballet's most basic foundations.

Wilmara Manuel and her 11-year-old daughter, Sasha, were at the world finals of a ballet competition, the Youth America Grand Prix, in 2015 when it happened. Shortly before the competition began, the young dancers were on the performance stage with their parents, warming up and preparing to dance the solos they’d been rehearsing for months.

As Wilmara, who is Black and originally from Haiti, and Sasha, who is biracial, stood there, a young white dancer looked around the stage, checking out the competition. “And her eyes land on Sasha,” Wilmara remembers, “and I saw her look [Sasha] up and down, and then look at her mom.

“And her mom said, ‘Don’t worry. They’re never really good anyway.’ ”

Wilmara did her best to contain her shock. Sasha didn’t hear what the white mom had said, and Wilmara wasn’t about to tell her, because “that’s not the thing I want to discuss 10 minutes before she takes the stage.” But Sasha could sense that something was amiss. “Just the look on my face, she was like, ‘What? What happened? What did she say?’ ” Wilmara brushed her daughter off.

Don’t worry. They’re never really good anyway. An entire worldview of white resentment of Black progress and excellence passed quietly from mother to child in just seven words.

That white mother could not fathom that Sasha, a biracial child with a Black mother, might be really good—as in very good, or truly good—at a traditionally white art form at which her child was presumably also quite proficient. She could not imagine that Sasha might deserve to be at that competition, might have qualified on her merit—her talent and skill and persistence—rather than because of what she might consider a misguided or even unjust attempt to diversify ballet by lowering standards. They’re not really good, but they are allowed to be here. In this space that is rightfully yours, in this art form that is rightfully yours. They’re never as good as the white girls, a sweeping generalization that grants no individuality, no humanity, to any nonwhite dancer. They’re all the same, and they never deserve to be here. But don’t worry. Your excellence is a given. You belong here, while their presence is conditional or even ill-gotten.

A few minutes later, Sasha took the stage and performed her solo. She ended up placing ahead of that white dancer.

From then on, Wilmara traveled with Sasha to every competition, paying the additional travel costs to make sure that, if something like that ever happened again, she’d be there to support her daughter.

“That has stuck with me,” she says. “And it’s one of the reasons I make the sacrifice and I go with her everywhere. Even if there are others going, I feel like I need to be around should comments like that pop up. I just don’t feel like I can take that chance, you know? And what cracks me up is that . . . she doesn’t even look as dark as I do, which makes me feel like, ‘Oh my God, if you were darker, like, what else?’ ”

Sasha grew up in a suburb of Indianapolis and is now 16. She trains at the Royal Ballet School in London, an exclusive training ground that serves as a feeder school for the Royal Ballet. It’s widely acknowledged to be one of the best ballet schools in the world.

Wilmara says that people often express their surprise at the quality of Sasha’s training and technique. “Oh wow, you’re really good,” Wilmara says by way of example. “Where do you train? Have you been dancing for a long time?” She says that while she tries to give these white people the benefit of the doubt, she knows what they usually mean, and she’d prefer they just come out and say it: “I’m surprised you’re that good. You’re Black and you’re dancing and you’re good.”

Now that Sasha is a little older, Wilmara talks to her about the racist assumptions embedded in those surprised comments. “You know she’s asking because she doesn’t think a person of your color can do this,” she’s told Sasha, who now “gets it when she hears that tone of voice.”

And, she says, she’s been frank with her daughter about the kind of resistance she should expect from the overwhelmingly white ballet establishment if she keeps excelling—which she shows every sign of doing.

It’s moms who do the bulk of the work of ballet parenting: the sewing of costumes, the schedule keeping for rehearsals and recitals. And when you’re a ballet mom to a dancer of color, there’s an even higher price to pay.

“Not everybody’s gonna be thrilled,” Wilmara says, paraphrasing her conversations with Sasha. “Even if you’re not a dancer of color, it’s cutthroat. And on top of that, you are a dancer of color, and so that poses another threat in some ways. So you have to be mindful of your things and what you are doing, and know what things are okay, and [pay attention to] when you are uncomfortable.”

This emotional labor, the work of helping young dancers understand what “that tone of voice” means and why it’s being used—or the work of deciding whether to tell your child about the racist remark you just overheard or absorb it yourself and shield them from it—is a part of parenting not demanded of mothers of white dancers.

Then there’s the payment in time and money required of Wilmara to make sure that Sasha’s ballet experience is as fair and worry-free as possible. Once, at a competition, Wilmara forgot to color in the “nude” pale pink straps on one of Sasha’s competition costumes. Wilmara scrambled to find brown foundation because none of the vendors at the competition had a leotard in Sasha’s skin color.

“Come on, people, you are here,” Wilmara remembers thinking. “There may not be that many [dancers of color], but they are all here and you should be able to bring various shades of nude leos.”

Succeeding in ballet, or even just surviving, requires extra talent, extra work, extra resilience, and extra sacrifices from dancers of color, especially Black and brown dancers, and their parents. White ballet moms might have to talk to their white daughters about how cutthroat ballet is. But they don’t need to issue additional warnings about how a white girl’s success will be received by that cutthroat culture, because almost all the successful girls and women in ballet are white.

“They’ve had to grow up a lot faster,” Wilmara says of Black and brown ballet dancers. “I think the ballet world makes you grow up a lot faster, but on top of that,” there are the “extra hurdles that other dancers don’t have to think about.” There are the overtly racist comments backstage before a performance and the subtly racist “compliments” after. There is time spent frantically searching for the right leotard or adapting the default pink leotard. There is the knowledge, internalized first by parents and then by their kids, that if you make it over all those hurdles your success will be viewed with suspicion and resentment—that ballet does not have a “diversity” problem; it has a white supremacy problem.

“Our kids,” Wilmara says, “are thinking about this and thinking about it early on.”

The organizing principle of ballet—of training, of performance, of making a ballet body—is control. Control of your rigid torso while your foot shoots upward from the hip in a battement. Control of a silent and compliant class of otherwise giggly 9-year-old girls. “The traditional and classical Europeanist aesthetic for the dancing body is dominated and ruled by the erect spine,” wrote dance scholar Brenda Dixon Gottschild in her landmark book The Black Dancing Body. “Verticality is a prime value, with the torso held erect, knees straight, body in vertical alignment. . . . The torso is held still.”

It all demands control. Control of your smiling face as your feet scream in your pointe shoes at the end of a long pas de deux. Control of your weight, of your turnout, of your stretched and strengthened feet that now arch into a shape no ordinary foot can make. “The ballet audience, attuned and habituated to view control as a prime value, applaud its display and are embarrassed when it isn’t fulfilled,” Gottschild wrote.

Discipline, order, adherence to strict and unquestioned rules. That’s what ballet is. When Gottschild asked Seán Curran, a white dancer and choreographer who performed with the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Company, what he pictured when he thought of white dance or white dancing bodies, he said, “Upright. . . . For some reason, ‘proper’ stuck in the head a bit, something that is built and made and constructed rather than is free or flows.” A body that is rigid, obedient, and disciplined, remade from something natural and unruly into something refined and well behaved. Proper. “Whiteness,” Curran said, “values precision and unison.”

Curran’s assessment identifies a central underlying prejudice of white supremacy: the belief that people of color, and their bodies, are wild. Uncivilized, animalistic, subhuman. That white people—who, by contrast, are assumed to be organized and civilized—have both a right and a responsibility to tame that which is untamed and impose order, precision, and unison on it. To suppress and control that which is savage; to press it into something that approaches whiteness but will never be truly white and thus never truly equal.

This is the logic that underpinned white colonization and American slavery. It is also the logic that makes racial segregation possible: that which is pure and organized must be kept separate from that which is profane and undisciplined. And central to this worldview is the idea that the work of white supremacy is unending, not because white supremacy is flawed, but because the very people it seeks to suppress are inherently inferior, naturally incapable of complying. Because of some inborn lack—of will, of understanding, of discipline—people of color will never fully obey, never properly assimilate, never be redeemed by whiteness. In this way, white supremacy perpetuates itself, justifying both its worldview and the permanent need for its existence.

It’s little wonder, then, that ballet—with its fixation on control, discipline, and uprightness—wraps itself so neatly around whiteness. It makes sense that white Americans, reared on the belief that whiteness is synonymous with order and refinement, also believe that people of color have no place, or a limited place, or a conditional place, in classical ballet.

Furthermore, it is easy to see how the ideal ballet body—so controlled, so upright—is everything that white supremacy imagines a Black body is not. And because of deeply ingrained American cultural associations with musculature, loose movement, brute force, and untamed sexuality, the Black body is believed to be everything a ballet body is not permitted to be.

“When we talk about the ballerina,” says Theresa Ruth Howard, a former dancer and a teacher, diversity strategist, and the founder and curator of the digital ballet history archive Memoirs of Blacks in Ballet (MoBBallet), “we’re talking about the ideal, our stereotype of the desirable woman, and that is reserved for white women.”

Howard has made a career of helping the people who run ballet companies and schools to examine their ideas about what makes for a “good” ballet body, asking them to question their biases about the inherent fitness of white bodies and unfitness of other bodies, especially Black bodies. She says that long-standing racist tropes about Black women’s bodies make Blackness and ballerinas seem antithetical.

“You have the trope of either the jezebel, the mammy, or the workhorse of the Black woman,” which are incompatible with desirability, fragility, and sexual purity, the ideal of white womanhood at the heart of the ballerina’s appeal.

“She’s desired. It’s the epitome of beauty, of grace, of elegance, and these are not adjectives that are assigned to Black women,” Howard says. “Especially not darker-skinned Black women. This is why the closer you look to the white European aesthetic as a Black woman, the better chance you have at occupying that role. Especially at a higher level.”

Despite the long tradition of Latin American dancers carving out successful professional careers in the U.S. and the enormous success of Misty Copeland—a light-skinned Black dancer whose ascent to the pinnacle of American ballet was a watershed moment for Black dancers and audiences alike—the archetypal ballerina is still a pale-skinned white woman with slender limbs, negligible breasts and hips, and long, sleek hair. In the American cultural imagination, the ballerina is still white.

George Balanchine famously said that “ballet is woman,” but that’s not the whole truth. Ballet is white woman, or, perhaps more precisely, white womanhood. Ballet is a stronghold of white womanhood, a place where whiteness is the default and white femininity reigns supreme.

Excerpted from Turning Pointe: How a New Generation of Dancers Is Saving Ballet from Itself by Chloe Angyal. Copyright © 2021. Available from Bold Type Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

323 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dancer: Barrington Hinds | Company: Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

PDF Willi Smith Street Couture PDF

PDF Willi Smith: Street Couture PDF

Willi Smith: Street Couture

[PDF] Download Willi Smith: Street Couture Ebook | READ ONLINEhttp://read.ebookcollection.space/?book=0847868192

Author : Alexandra Cameron Cunningham

Publisher :

ISBN : 0847868192

Publication Date : --

Language :

Pages :

To Download or Read this book, click link below:

http://read.ebookcollection.space/?book=0847868192

Synopsis : PDF Willi Smith: Street Couture PDF

African-American fashion designer Willi Smith, pioneer of streetwear and visionary collaborator, finally gets his due in an exuberant celebration of his life and work.Before Off-White, before Hood By Air, before Supreme, there was WilliWear. Willi Smith created inclusive and liberating fashion: I don't design clothes for the queen, but the people who wave at her as she goes by, he said. A rising star from the time he left Parsons, Smith went on to found WilliWear with Laurie Mallet in 1976 and became one of the most successful designers of his era by his untimely death in 1987. Smith broke boundaries with his streetwear, or street couture, and trailblazed the collaborations between artists, performers, and designers commonplace today in projects with SITE Architects, Nam June Paik, Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Spike Lee, Dan Friedman, Bill T. Jones, and Arnie Zane. Essays by leading figures from the worlds of fashion, art, architecture, and cultural studies paired with never before-seen images and ephemera make Willi Smith essential reading for the history of streetwear culture and the evolution of fashion from the 1970s to today.

1 note

·

View note