#Bugti Refugees Afghanistan

Text

آج شہید گل بھار بگٹی کے بیٹے شہید در خان بگٹی کی 13ویں برسی ہے، 25 مارچ 2011 اسپین بولدک افغانستان میں پاکستانی خفیہ ایجنسی نے خودکشی ہملے میں شہید کیا تھا جہاں وہ پناہ گزین کی زندگی گزار رہے تھے

#Today 13th anniversary of Shaheed Dar Khan Bugti#25 March 2011#who was martyred in a suicide attack by Pakistan's intelligence agency in Af#Shaheed Gul Bahar Bugti#balochistan#baloch#bugti#Bugti Refugees Afghanistan#Kandahar

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

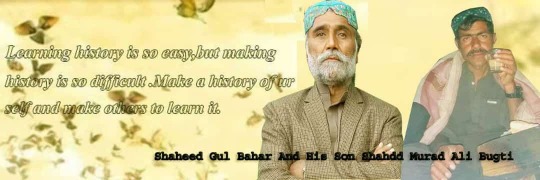

Yesterday marks the 3rd anniversary of the martyrdom of Shaheed Gul Bahar Bugti and his son Martyr Murad Ali Bugti. He sacrificed his life for the freedom and rights of his people. Let us pay tribute to his bravery and commitment to the cause of Balochistan's independence. #ShaheedGulBaharBugti #ShaheedMuradAliBugti

#BalochistanFreedomStruggle#Martyr Murad Ali Bugti#Martyr Gul Bahar Bugti#Refugees Baloch#Refugees Bugti#bugti#baloch#martyr#بلوچ#balochistan#بلوچستان#afghanistan#dera bugti#brp#freedom#Struggle Balochistan freedom

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Located at the western edge of the famed Khyber Pass, Torkham has seen generations of Afghans flee and return during the tumultuous four decades of war that have blighted the nation.

Many fled the Soviet invasion in the 1980s and the mujahideen’s long, eventually successful fight back. Others took flight during the civil war that erupted following the Soviet retreat that led to the Taliban’s initial rise.

A new generation went to Pakistan in the aftermath of September 11 attacks, ebbing and flowing during the near two decades of conflict that followed. The Taliban’s return to power in 2021 following the United States’ chaotic withdrawal sparked another wave of some 600,000 refugees.

Now Afghans from all those different generations are being told to go back.

Pakistan’s caretaker Interior Minister Sarfraz Bugti has previously said security concerns were behind the deportation order, claiming that Afghan nationals had carried out 14 of the 24 major terrorist attacks that have taken place in Pakistan this year.

Been trying to check if the refugees fled Afghanistan due to some sort of ethnic hatred but haven't seen that mentioned as a reason so far.

219 notes

·

View notes

Text

Afghan refugees who fled their country to escape from decades of war and terrorism have become the unwitting pawns in a cruel and crude political tussle between Pakistan’s government and the extremist Taliban as their once-close relationship disintegrates amid mutual recrimination.

On Oct. 3, Pakistan’s government announced that mass deportations of illegal immigrants, mostly Afghans, would start on Nov. 1. So far, at least 300,000 Afghans have already been ejected, and more than a million others face the same fate as the expulsions continue.

The bilateral fight appears to center on Kabul’s support for extremists who have wreaked havoc and killed hundreds in Pakistan over the last two years—or at least that is how Islamabad sees it, arguing that it is simply applying its own laws. The Taliban deny accusations that they are behind the uptick of terrorism in Pakistan by affiliates that they protect, train, arm, and direct.

Mass deportations are a sign that Pakistan is “putting its house in order,” said Pakistan’s caretaker minister of interior, Sarfraz Bugti. “Pakistan is the only country hosting four million refugees for the last 40 years and still hosting them,” he said via text. “Whoever wanted to stay in our country must stay legally.” Of the 300,000 Afghans already ejected, none have faced any problems upon returning, he told Foreign Policy. As the Taliban are claiming that Afghanistan is now peaceful, he said, “they should help their countrymen to settle themselves.”

“We are not a cruel state,” he said, adding: “Pakistanis are more important.”

The Taliban—who, since returning to power in August 2021, have been responsible for U.N.-documented arbitrary detentions and killings, as well forcing women and girls out of work and education—have called Pakistan’s deportations “inhumane” and “rushed.” Taliban figures have said that the billions of dollars of international aid they still receive are insufficient to deal with the country’s prior economic and humanitarian crises, let alone a mass influx of penniless refugees.

The expulsions come after earlier efforts by Pakistan, such as trade restrictions, to exert pressure on Kabul to rein in the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), the Pakistani Taliban, whose attacks on military and police present a severe security challenge to the Pakistani state. Acting Prime Minister Anwar ul-Haq Kakar said earlier this month that TTP attacks have risen by 60 percent since the Taliban regained control of Afghanistan, with 2,267 people killed.

The irony is that Pakistan bankrolled the Taliban throughout their 20-year insurgency following their ouster from power during the U.S.-led invasion in 2001. Taliban leaders found sanctuary and funding from Pakistan’s military and intelligence services. When the Taliban retook control of Afghanistan in 2021, then-Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan congratulated them, as did groups such as al Qaeda and Hamas. But rather than continuing as Islamabad’s proxy, the Taliban have reversed roles, providing safe haven for terrorist and jihadi groups, including the TTP.

“While it’s still too early to draw any conclusions on policy shifts in Islamabad, it appears that the initial excitement about the Taliban’s return to power has now turned into frustration,” said Abdullah Khenjani, a former deputy minister of peace in the previous Afghan government. “Consequently, these traditional [Pakistani state] allies of the Taliban are systematically reassessing their leverage to be prepared for potentially worse scenarios.”

Since the Taliban’s return, around 600,000 Afghans made their way into Pakistan, swelling the number of Afghan refugees in the country to an estimated 3.7 million, with 1.32 million registered with the U.N. High Commission on Refugees. Many face destitution, unable to find work or even send their children to local schools. The situation may be even worse after the deportations: Pakistan is reportedly confiscating most of the refugees’ money on the way out, leaving them in a precarious situation in a country already struggling to create jobs for its people or deal with its own humanitarian crises.

Border crossings between Pakistan and Afghanistan have been clogged in recent weeks, as many Afghan refugees preempted the police round-up and began making their way back. Media have reported that some of the undocumented Afghans were born in Pakistan, their parents having fled the uninterrupted conflict at home since the former Soviet Union invaded in 1979. Many of the births were not registered.

Meanwhile, some groups among those being expelled are especially vulnerable. Hundreds of Afghans could face retribution from the Taliban they left the country to escape. Journalists, women, civil and human rights activists, LGBTQ+ advocates, judges, police, former military and government personnel, and Shiite Hazaras have all been targeted by the Taliban, and many escaped to Pakistan, with and without official documents.

Some efforts have been made to help Afghans regarded as vulnerable to Taliban excess if they are returned. Qamar Yousafzai set up the Pakistan-Afghanistan International Federation of Journalists at the National Press Club of Pakistan, in Islamabad, to verify the identities of hundreds of Afghan journalists, issue them with ID cards, and help with housing and health care. He has also interceded for journalists detained by police for a lack of papers. Yet that might not be enough to prevent their deportation.

Amnesty International called for a “halt [to] the continued detentions, deportations, and widespread harassment of Afghan refugees.” If not, it said, “it will be denying thousands of at-risk Afghans, especially women and girls, access to safety, education and livelihood.” The UNHCR and International Organization for Migration, the U.N.’s migration agency, said the forced repatriations had “the potential to result in severe human rights violations, including the separation of families and deportation of minors.”

Once back in Afghanistan, returnees have found the going tough, arriving in a country they hardly know, without resources to restart their lives, many facing a harsh Himalayan winter in camps set up by a Taliban administration ill-equipped to provide for them.

Fariba Faizi, 29, is from the southwestern Afghanistan city of Farah, where she was a journalist with a private radio station. Her mother, Shirin, was a prosecutor for the Farah provincial attorney general’s office, specializing in domestic violence cases. Once the Taliban returned to power, they were both out of their jobs, since women are not permitted to work in the new Afghanistan. They also faced the possibility of detention, beating, rape, and killing.

Along with her family of 10 (parents, siblings, husband, and toddler), Faizi, now eight months pregnant with her second child, moved to Islamabad in April 2022, hoping they’d be safe enough. Once the government announced the deportations, landlords who had been renting to Afghans began to evict them; Faizi’s landlord said he wanted the house back for himself. Her family is now living with friends of Yousafzai, who also arranged charitable support to cover their living costs for six months, she said.

With no work in either Pakistan or Afghanistan, Faizi said, they faced a similar economic situation on either side of the border. In Pakistan, however, the women in the family could at least look for work, she said; their preference would be to stay in Pakistan. As it is, they remain in hiding, afraid of being detained by police and forced over the border once their visas expire.

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

By Asif ShahzadISLAMABAD (Reuters) -Pakistan on Tuesday ordered all illegal immigrants, including 1.73 million Afghan nationals, to leave the country or face expulsion after revealing that 14 of 24 suicide bombings in the country this year were carried out by Afghan nationals.It was not immediately clear how Pakistani authorities could ensure the illegal immigrants leave, or how they could find them to expel them.Islamabad's announcement marks a new low in its relations with Kabul that deteriorated after border clashes between the South Asian neighbours last month."We have given them a November 1 deadline," said Interior Minister Sarfraz Bugti, adding that all illegal immigrants should leave voluntarily or face forcible expulsion after that date.Bugti said some 1.73 million Afghan nationals in Pakistan had no legal documents to stay, adding a total of 4.4 million Afghan refugees lived in Pakistan."There are no two opinions that we are attacked from within Afghanistan and Afghan nationals are involved in attacks on us," he said. "We have evidence."Islamabad has received the largest influx of Afghan refugees since the Soviet invasion of Kabul in 1979.Bugti was speaking in Islamabad after civil and military leaders met the prime minister and army chief to discuss law and order after a recent spate of militant attacks.The violence has seen an unusual uptick since local Taliban militants known as Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), an umbrella group of hardline Sunni Islamist militants, revoked a ceasefire with the government late last year.The TTP wants to overthrow the Pakistani government to replace it with its strict rule under Islamic law.Two suicide bombings targeted religious gatherings in Pakistan last week, killing at least 57 people. The TTP denied involvement. Bugti said that one of the suicide bombers had been identified as an Afghan national.Islamist State also operates in the Afghan border regions and has been involved in attacks in Pakistan.The Pakistani military has conducted several offensives against Islamist militants, mainly in the rugged mountainous region along the Afghan border, which it says forced them to flee to Afghanistan.Islamabad alleges that the militants use Afghan soil to train fighters and plan attacks inside Pakistan, a charge Kabul denies, saying Pakistani security is a domestic issue.There was no immediate response from Kabul to Bugti's comments.(Reporting by Asif Shahzad; Editing by Jon Boyle and Nick Macfie)

0 notes

Text

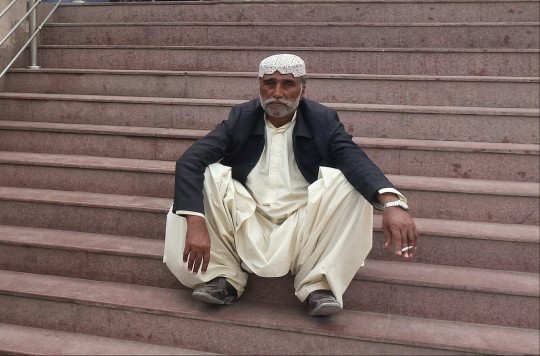

Shaheed Gul Bahar Bugti

شہید گل بھار بگٹی

#Shaheed Gul Bahar Bugti#Bugti#martyr#balochistan#baloch indepedence#baloch#afghanistan#kandahar#bugti refugees#Refugees#Baloch Refugees#ڈیرہ بگٹی#بلوچستان#بلوچ#بگٹی#بگٹی مہاجریں#بلوچ مہاجریں#افغانستان#کندھار#شہید#شہید گل بھار بگٹی

0 notes

Text

Why I Left Home: The story of a Baloch refugee

Noroz Hayat September 19, 2019 Featured

I am obsessed with reading novels, short stories, or any literature about people who left their homes, were expelled from their countries or persecuted. A part of keeping informed is I don’t get weary of watching movies and documentaries about the lives of refugees or victims of torture and imprisoned for unjust reasons.

Of course, watching these movies now is different from when I was a kid in the late 90s, enjoying the silver screen with friends and cousins. Now the movies I watch are about real life, and they feel close to my real life.

When I go to bed after watching a movie in any language, I wake in the middle of the night, scared, reliving the scenes as if I am being abducted or tortured, or our village is being burned or evacuated, or I am running away from some army man, always afraid of what lies ahead, just like in the movies. This is painful, but is now a part of my life, part of why I left my home. I cannot run away from the reality of confronting it. Being aware of the trauma and the trials of others has made me realize that I am not the only victim of war, subsequent loneliness and homesickness. Which is why I decided to share my story too.

I was born in a small village called Khairabad, near Kech, in the south of Balochistan. I imagined in my wildest thoughts that one day I would be sitting alone, lonely, in the corner of a coffee shop writing the story of leaving my home, my family, friends, relatives, and carry along the childhood memories. I now understand how important they are and what they mean to a person.

Not only watching movies was fun, but my childhood was, as most childhoods are, innocent of the country’s political situation. As the only son of my parents, I was privileged to receive an abundant amount of love and affection from my cousins, aunts, uncles, and extended family. Daily life was going to the mud-built structure that served as a school, playing cricket after school with cousins and friends and occasionally herding the sheep to the fields. In the summer during school break, I would join my uncle and grandfather at date-palm farms, where my grandfather would sell the dates to city folks from Karachi who would come to buy Makurani dates at rock-bottom prices that only we offered.

Getting older was exciting, because our world expanded, or so we thought. Together with my cousins, we could not wait to go to Turbat, the nearest city that was 40 miles (64 kilometers) away. The only public transport from our village were Toyota pickups that took over an hour to reach the city on dirt roads. Once there, we would buy Balochi Chawat (traditional footwear) and walk around the streets of Turbat city.

Rahmat-e-Sheeren, Gadi Chok, and Balochistan Music Center were my favorite places in the city. Whenever I would go to Turbat, I would buy one Balochi cassette of music and never missed the Rahmat-e-Shereen sweets and samosas. It was a different world full of more adolescent kind of fun. My mother had promised me that when I graduate from high school that she would send me to Turbat for higher education. So, whenever I went to Turbat and looked at the buildings of Atta Shad Degree College, I told myself that I would be there someday, attending college classes in those buildings.

It wasn’t until I graduated from high school that I came to know that the land where I was born had already seen three political battles between Baloch nationalists and the Pakistani military. All of the conflicts involved much bloodshed, including of course people who were fighting for their land and justice. The people of Balochistan suffered the killing and persecution of numerous political leaders and as many activists, of whom if they weren’t killed took refuge in Afghanistan and the neighboring province of Sindh. Fortunately, Turbat, and the town where I grew up had not been affected by these trials as much as other towns, hence I was able to grow up somewhat innocent and enjoy being a child safe under the watchful eyes of my family.

Kech

My mother was good for her word: In 2006, I gained admission in Atta Shad Degree College and moved to Turbat. There were three dormitories for students on campus known as New, Old, and Complex. I was assigned to room six in the Old building. Four students, who were all from different villages and towns in the Kech district, and I shared the room. I also shared an education with these friends and roommates that wasn’t limited to the classroom.

As I learned my way around campus, I saw much writing and graffiti written in red paint and spray paints. It was written by the Baloch Student Organization (BSO). The various graffiti messages read:

“We didn’t accept the state census in Balochistan.”

“Kalam may tawar kitab may rahsoon. (The Pen is our guide, the Book our Leader!)”

“BSO ke rehnumabo ki griftari ryasati deshatgardi hai. (The arrest of BSO leaders is a form of state terrorism!)”

“Warna raj e bandat ant. (The youths are the future of the nation)”

“Army, get out of Balochistan.”

“We need education, not jail.”

This wasn’t the first time I had heard of the BSO. The first time I heard the name of the organization was in 2003, when I was in school. One of my cousins told me that some BSO walas were visiting our school and arranging a study circle type of event for the students. It was the first and last event of any kind that was conducted for students during all my school years. This organization seemed to care.

Apart from seeing BSO footprints around the campus and my singular knowledge of its existence from my cousin, I felt like a person who was given a new set of eyes, who had just popped out of his old environment into a contemporary world. College life was an entirely new experience for me. Not just the interaction with my roommates, but the daily interaction with several students from different towns and villages gave me a broader perspective on people.

Reading various works of literature that I had never before encountered, gave me a more reflective understanding of life. I made new friends and occasionally attended BSO study groups, where I sat around sipping the bitter and sweet tea at Pyary’s Canteen and smoking cigarettes like a grown-up man. I had crossed the threshold of adulthood by now.

Little did I know what lay beyond that initial step into being “grown-up”. How things would change so fast or how I ended up here sitting at this coffee shop writing, in exile. I am still asking myself these questions.

On August 27, 2006 the military entered the college grounds armed with loaded weapons and the arms of war. Faster than anyone could raise an alarm, almost one hundred students and staff of the college were taken becoming hostages of the military. Knowing this was illegal, just one of the offenses the military was committing, the principle of the school went out to tell the army Major leading the invasion that, without any official notice, he was not allowed to enter the college premises. The military man started shouting. I still remember his exact words: “Who the hell are you dictating what I can and cannot do? And what my authorities are!!!”

Naturally, the petrified students who were not taken by the military, were left to stand by, unable to believe what was happening. Remember, we were from an area that had not been directly affected by the political upheaval, this was not comprehensible to us.

The teachers themselves told us that the military had never forced themselves on college property before. This was an escalation of a situation none of us were well-informed of at the time. Unbeknownst to us at the college, the day before on August 26, a Baloch politician named Nawab Akbar Bugti, was assassinated in a military operation in Dera Bugti, his home town. Reacting to the assassination, student activists and politicians were out protesting against the military. In response, the military then put a curfew on the city of Turbat and other parts of Balochistan. The military had come to our school, as they had to colleges and universities across Balochistan to cordon off the areas and prevent students from going out and protesting against the military. When the security forces left the campus, I breathed a sigh of relief – as I’m sure everyone else did – packed my bags and left the city.

The invasion of the military was too much for me. But there was nothing for me to do at home and no space to smoke my cigarettes. I got bored. Even though I didn’t want to return, it was for me the only place to go at the time. So, after a week I returned to Turbat and college.

Returning to the college, I picked up where I left off from and started the same routine. However, it was not the same anymore. Turbat city had changed now, and it seemed to have spread throughout Balochistan. There was a feeling of trepidation. Students were caught up in politics, demonstrating and protesting against the state for the exploitation of Balochistan’s resources and the mistreatment of the people. The assassination and military incursion had awakened everyone to become involved, to be heard.

Of course, the military didn’t stand this. This was what they had tried to prevent in the first place, when they first showed up at the colleges and universities. On the other hand, some Baloch nationalists were holding political gatherings and raising the issue that Pakistan has been exploiting not only the resources, but the education and culture of Balochistan for the past six decades. Regardless of any negotiations that took place, the military seized and threw students in jail all over Balochistan. In an injustice as old as time, these activists were being put in jail for believing in and voicing the rights of Baloch to have a say in the governance of their own land.

The BSO

Although Aristotle wrote that the man is by nature a social animal, it is not entirely the reason I took the steps that I did leading to further escalate towards my exile. An intellectual capacity for seeing and understanding moral imperatives and wrongs was awakened in me. Being part of the Baloch students community, I started attending political gatherings at the college. There were two tiers of academic study at the college: one was regular classes with professors and the second was the Study Circle, which was arranged by students once or twice a week to talk and get insight on international politics, the political situation surrounding us in Balochistan, and literature and writings on democracy and liberalism. To add to our learning in the study circles, we invited Baloch intellectuals from different specialties to educate us.

From this training, I learned that as a people, we Baloch have a distinct culture and history which is different from the other nations in Pakistan, especially from the ruling majority class. I came to know a different version of history, one which was always hidden by the state from us. This different version of Baloch history is a history of subjugation and manipulation of our people by the state. This most recent version of Baloch history that I learned made me more critical of the everyday injustices that were occurring – had been there for a long time – in Balochistan.

Despite the very important learning that was taking place, I left Atta Shad Degree College after a year and a half. One day I just took my clothes, folded them in a dirty bag, and left the dorm with teary eyes. But I left my books in my room, just for the self-satisfaction that I would come back some day. There were two reasons I decided to leave. First was financial. My father had passed away when I was in 8th grade at school, and the amount of money he left behind was not enough to continue my higher education. The second reason was the city was getting more fraught with fear. The student dormitories were under watch by the Pakistani intelligence agencies. There was a big military base and secret service building near the college. Every night unknown people freely roamed the college grounds and went through the dormitories. There were suspicious cars with tinted mirrors that followed students when they arrived and left the main gate of the school. I was disillusioned, I knew I couldn’t stay.

Once home, I tried to ask relatives in the gulf countries to get me a labourer’s visa to get me out of there. But this wasn’t the path my mother was willing to let me go down. She was convinced that I must finish college. When I insisted that I could not go back to college in Turbat, she refused to give up on me following a higher education. She suggested going to school elsewhere. “Why don’t you go to Karachi? Karachi is a safe city. I will arrange some money for you.” And that’s just what she did. After staying at home for four months, I went to Karachi in August 2007 because of my mother’s persistence.

Karachi

It was a challenge to go back to school, and I faced a dilemma even though I had reached Karachi: Should I continue in school or should I return home and try to find a visa? This time I asked some relatives in Oman, Qatar and UAE, but did not receive any response. Which led to my decision to stay in Karachi until I finished my master’s degree.

Four other students, all from my village, and I rented a two-bedroom tiny apartment in Gulistan- e-Johar. The others had arrived before me and knew the lay of the land. Just to help me along, one of my roommates wrote on a piece of paper the names of three buses and where they would take me: ‘11-A will take you to the Liaquat Library, 4X will take you to the tuition center, and Lucky Star brings you home.’ That piece of paper and it’s directions were the start of a new life in Karachi.

In Liaquat Library, I met with several Baloch students who had traveled a hundred miles to come to Karachi to fulfill their desire for knowledge. Some of whom I met at the library were students enrolled at colleges, some from different universities. We were all there for the same reason: we had all learned a thing or two from the study circles of BSO back in our hometowns or and brought that knowledge to Karachi with us.

During this time in Karachi, my friends and I were treated as if we were illiterate, ignorant people. We heard many times, both in our classes and in public places that we Baloch lived in the mountains, were not civilized people, violent, uneducated, did not know how to speak proper Urdu, and just don’t wear decent clothes. We were frightened to go into non-Baloch dominant areas.

Despite being citizens of Pakistan, we were considered and treated as third-class citizens. My perspective and understanding of myself and fellow Baloch’s standing changed when I faced these biases. Luckily, during this time I was learning other things too which was strengthening my resolve, and the easy access to books, libraries, and the internet was aiding the person I was becoming. I had always wanted to be a social worker and accomplished this goal, first earning an undergraduate degree in 2009 in Sociology and then a Master’s Degree in Social Work in 2013.

Subsequent to completing my education, I worked for a couple of non-governmental organizations helping people as a social worker. However, despite my developing character and working in my chosen field and corporeal self being in Karachi, my thoughts were in Balochistan, my homeland.

My thoughts were soon to be cemented forever with Balochistan as it became harder to visit. In 2009, the Pakistani military started a new tool, a program called “Kill and Dump” to quell any kind of resistance, imagined or real, to their authority. This was intended to stop the Baloch political movement which was gaining more and more popular support in every corner of Balochistan. It was much stronger than the three previous political movements and especially since the Baloch youth were participating in it from the beginning.

The army first abducted those Baloch leaders and activists who condemned state absolutism in their public gatherings and demanded justice from the West, calling out to human rights organizations to intervene in Balochistan to stop state forces from exploiting Baloch resources. The military’s ruthlessness didn’t end there. Within a couple of years, the state deployed a hundred thousand security forces in different towns in Balochistan, built more security checkpoints on highways, where they checked every passenger’s identification card. It was also announced in print and electronic media that the state will punish the supporters and facilitators of the Baloch movement.

Mostly student activists, guilty only of trying to have their voices heard, were abducted from security check-posts. Every two to three days, they would “disappear” people from Bozi checkpoint, Gwadar Zero Point, Uthal checkpoint, and Khuzar checkpoint, and their decomposing bodies were dumped in Murgap, Turbat, Uthal, Quetta, Khuzdar and other parts of Balochistan.

My journey of social work and helping others didn’t go far because of the “Kill and Dump” operations. I was afraid I would be abducted and killed like many other students and activists. From 2009 to 2015, during my time in Karachi, we lost several BSO’s activists and some close friends. Zakir Majeed, a M.A English literature student and Senior Vice Chairman of BSO, was forcibly disappeared in Mastung in June 2009, and is still missing; no one knows about him. Qambar Chakar, 24, a student of Balochistan University of Information Technology Engineering and Management Science (BUITEMS), was abducted with his cousin in November 2010 from his home. Later his cousin Irshad Baloch was released, but Qambar Chakar’s decomposed body was found dumped in Murgaap, Turbat along with another missing student Ilyas Nazar, only 22, in January of 2011. Raza Jahangir, a good friend and Secretary General of the BSO, was killed in August 2013 with another activist Imdad Baloch in a military operation in Turbat. BSO’s Chairman Zahid Baloch was abducted in March, 2014 in Quetta, and he is still missing along with others.

With tensions and apprehensions escalating, traveling became more difficult. I had to cross ten to eleven security check posts, show my identification card to the army-guard whenever I went home from Karachi. I was asked numerous prying questions at the security checkpoints, and I had the feeling that they were just trying to pinpoint my movements and get information that was innocent enough, but that would be used against me for some unknown reason. It was getting more and more dangerous.

The last time I went home to Khairabad was in June 2014. After that, I stopped going back to the place where I grew up, and the place where my father, grandfather, grandmother, and uncle are buried. The place I call my homeland. My home.

In August 2015, I landed in the United States with the hope of finding a safe shelter to live peacefully for the rest of my life.

The author tweets at @noroz_hayat

0 notes

Text

US designates BLA as terror outfit

New Post has been published on https://www.hidoose.com/us-designates-bla-as-terror-outfit/

US designates BLA as terror outfit

ISLAMABAD: In a major diplomatic breakthrough, the United States (US) on Monday listed the Balochistan Liberation Army (BLA) to Specially Designated Global Terrorist (SDGT) organisations.

The listing was made at the official site of US Department of Treasury.

The development comes well ahead of Prime Minister Imran Khan’s visit to the US which would pave the way for further galvanising the two countries that have witnessed bilateral relations souring since 2011.

Pakistan had designated the BLA as a terrorist organisation on April 7, 2006, after the group conducted a series of attacks targeting security personnel.

On July 17, 2006, the British government followed suit, listing the BLA as a “proscribed group” based on the Terrorism Act 2000, although the UK has harboured Hyrbyair Marri, leader of the BLA, as a refugee, something former army chief General (r) Raheel Sharif had protested against.

The group’s actions have been described as terrorism by the United States Department of State and European Union too.

However, the new listing of BLA to SDGT has put sanctions on the funding and movement of the terrorists affiliated with the BLA which of late has targeted several Chinese installations and Chinese nationals working on projects linked to China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC).

BLA is a Baloch separatist organisation based in Pakistan’s Balochistan province. It became publicly known during the summer of 2000 after it claimed credit for a series of bombing attacks on Pakistani authorities. It has been claimed that Brahumdagh Bugti is one of the founders of the BLA.

Since 2004, the BLA has waged a limited war against the state. It is operating mainly in Balochistan, the largest province of Pakistan, where it carries out attacks against the Pakistan Armed Forces.

Pakistan has accused the BLA of being an Indian proxy, and Indian consulates in Kandahar and Jalalabad, Afghanistan, for providing arms, training and financial aid to the BLA in an attempt to destabilise Pakistan.

After the death of Aslam Baloch alias Achu in Kandahar, who claimed several attacks against Chinese nationals in Balochistan, the Afghan officials claimed that the Afghan police chief Abdul Raziq Achakzai had housed Aslam Baloch and other separatists in Kandahar for years.

Similarly, Afghan media outlet, Tolo News also claimed that Aslam Baloch has been residing in Afghanistan since 2005.

0 notes

Text

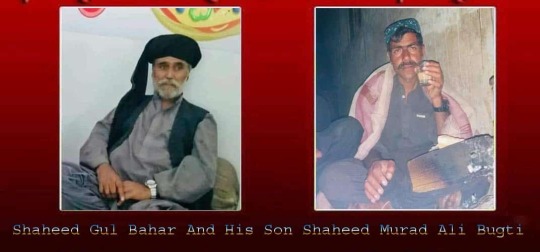

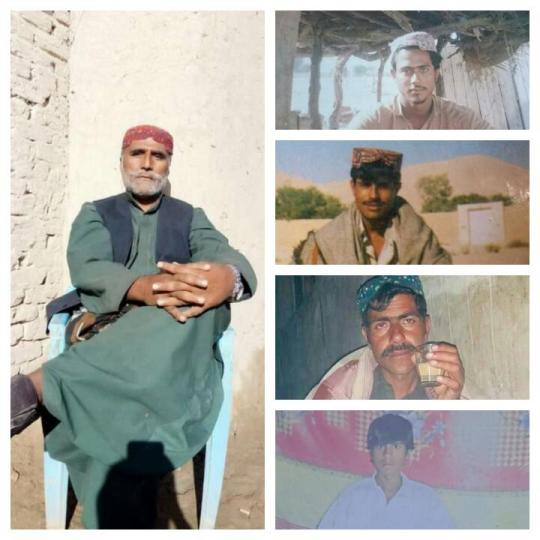

Shaheed Gul Bahar Bugti And his son Shaheed Murad Ali Bugti

Today is the 3rd martyrdom anniversary of Martyr Gul Bahar Bugti and Martyr Murad Ali Bugti, they were killed by Pakistani secret agencies in Kandahar Afghanistan on 20th December 20...

#balochistan#bugti#afghanistan#baloch#freedom#wazir khan bugti#shaheed gul bahar bugti#english news#news urdu#Martyr Murad Ali Bugti#Dera Bugti#refugeesbaloch#baloch refugees#Bugti Refugees#free balochistan#baloch republican party#Struggle Balochistan#Struggle#Freedom Balochistan Struggle#BRP#Leader BRP

1 note

·

View note

Text

Shaheed Gul Bahar Bugti Baloch

The fragrance of the homeland will come from our dust.

Our blood is included in the soil of this homeland

#Bugti#Baloch#Balochistan#Baloch national#Refugees#baloch refugees#Refugees Afghanistan#kandahar#بگٹی مہاجرین#ڈیرہ بگٹی#بلوچستان#افغانستان#بگٹی#بلوچ#بلوچ مہاجرین#کندھار#شہید گل بہار بگٹی#شہید#martyr#BRP#Baloch Republican party#Kandahar of Afghanistan#Homeland#watan

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Remembering the Sacrifice: 10th Martyrdom Anniversary of Shaheed Nihal Khan Bugti and Shaheed Zar Khan Bugti

Introduction:

As we approach the solemn occasion of the 10th martyrdom anniversary, we take a moment to reflect on the lives and sacrifices of two brave souls, Shaheed Nihal Khan Bugti and Shaheed Zar Khan Bugti. It's been a decade since they were tragically targeted and killed by Pakistan’s intelligence agencies in Spin Boldak, #Afghanistan. The pain of their loss still lingers, but their memories serve as a poignant reminder of the challenges faced by those who stand for justice and truth.

The Tragic Incident:

"It's will be the 10th martyrdom anniversary of Shaheed Nihal Khan Bugti and Shaheed Zar Khan Bugti." On that fateful day, these two individuals, known for their unwavering commitment to their cause, became victims of a heinous act orchestrated by Pakistan’s intelligence agencies. Spin Boldak, a region in Afghanistan, witnessed the tragic end of their lives, leaving behind a void that can never be filled. As we commemorate their sacrifice, it's essential to delve into the circumstances surrounding their targeted killings.

Legacy of Courage:

The legacy of Shaheed Nihal Khan Bugti and Shaheed Zar Khan Bugti is not merely confined to the circumstances of their untimely demise. Their lives were a testament to unwavering courage and dedication to the principles they believed in. "It's will be the 10th martyrdom anniversary of Shaheed Nihal Khan Bugti and Shaheed Zar Khan Bugti," and it's an opportune time to celebrate the indomitable spirit that defined their existence.

Their contributions extended beyond geographical boundaries, resonating with those who shared their vision for a just and peaceful world. Their commitment to their cause serves as an inspiration for others to stand up against oppression and injustice.

The International Response:

In the aftermath of the tragic incident in Spin Boldak, the international community reacted with concern and condemnation. The targeted killings of Shaheed Nihal Khan Bugti and Shaheed Zar Khan Bugti raised questions about the role of intelligence agencies in perpetuating violence beyond their borders. Countries around the world called for a thorough investigation into the matter, urging accountability for those responsible.

The incident also underscored the delicate geopolitical situation in the region, highlighting the need for diplomatic efforts to address such issues collaboratively. The hashtag #Afghanistan trended on social media platforms, drawing attention to the broader implications of extrajudicial actions by intelligence agencies.

Remembering Shaheed Nihal Khan Bugti and Shaheed Zar Khan Bugti:

As we approach the 10th martyrdom anniversary, it's imperative to remember Shaheed Nihal Khan Bugti and Shaheed Zar Khan Bugti not just as victims but as symbols of resilience and bravery. "It's will be the 10th martyrdom anniversary of Shaheed Nihal Khan Bugti and Shaheed Zar Khan Bugti," and in their memory, we must strive to continue the fight for justice, truth, and human rights.

Their families, friends, and supporters have kept their memories alive through various initiatives and tributes. Commemorative events, social media campaigns, and artistic expressions have helped ensure that the legacy of these two remarkable individuals endures, transcending the circumstances of their tragic end.

The Ongoing Struggle:

In the years following the incident, the struggle for justice and accountability has continued. Advocacy groups and human rights organizations have tirelessly worked to shed light on the circumstances leading to the targeted killings of Shaheed Nihal Khan Bugti and Shaheed Zar Khan Bugti. "It's will be the 10th martyrdom anniversary of Shaheed Nihal Khan Bugti and Shaheed Zar Khan Bugti," and the quest for truth remains an ongoing endeavor.

International organizations, including the United Nations, have been urged to play a more active role in ensuring that such incidents are thoroughly investigated, and those responsible are held accountable. The voices calling for justice echo not only in Afghanistan but resonate globally, emphasizing the interconnectedness of human rights and the collective responsibility to protect them.

The Importance of Remembrance:

As we mark the 10th martyrdom anniversary, it's crucial to recognize the significance of remembrance in fostering a collective commitment to justice and accountability. "It's will be the 10th martyrdom anniversary of Shaheed Nihal Khan Bugti and Shaheed Zar Khan Bugti," and by remembering their sacrifice, we honor not only the individuals but also the ideals they stood for.

Remembrance serves as a powerful tool in preventing history from repeating itself. By acknowledging the past, we pave the way for a future where such injustices are not tolerated, and individuals are free to express their beliefs without fear of reprisal. The act of remembrance, therefore, becomes a collective responsibility, transcending borders and uniting people in the pursuit of a just and compassionate world.

Conclusion:

In commemorating the 10th martyrdom anniversary of Shaheed Nihal Khan Bugti and Shaheed Zar Khan Bugti, we pay tribute to lives that were cut short in the pursuit of justice and truth. "It's will be the 10th martyrdom anniversary of Shaheed Nihal Khan Bugti and Shaheed Zar Khan Bugti," and as we reflect on their sacrifice, let us recommit ourselves to the principles they held dear. Their legacy lives on in the hearts of those who continue to fight for a better world, free from oppression and injustice.

#Shaheed Zar Khan Bugti#Shaheed Nihal Khan Bugti#baloch#بلوچ#bugti#martyr#بلوچستان#balochistan#afghanistan#dera bugti#freedom#brp#Spin Boldak#Refugees

0 notes

Text

The Tragic Tale of Shaheed Gul Bahar Bugti and Martyr Murad Ali Bugti: Baloch Refugees in Afghanistan

Introduction:

In the heart-wrenching landscape of conflict and displacement, the story of Shaheed Gul Bahar Bugti and his son Martyr Murad Ali Bugti stands out as a tragic reminder of the price some pay for their pursuit of justice and nationalism. This blog delves into the life of Gul Bahar Bugti, a brave Baloch nationalist, and his son Murad Ali Bugti, who were refugees living in Afghanistan. The fateful incident occurred on Sunday, 20th December 2020, when they were mercilessly martyred by a motorcycle-riding assailant, believed to be linked to Pakistani secret agencies.

The Life and Legacy of Gul Bahar Bugti:

Gul Bahar Bugti, a name synonymous with bravery, fearlessness, and Baloch nationalism, was a prominent figure in the struggle for the rights of the Baloch people. His commitment to the cause was unwavering, even in the face of unspeakable personal loss. Prior to the tragic incident in Kandahar, Gul Bahar Bugti had already endured the heartbreaking loss of four family members - his grandson Nihal Khan Bugti, nephew Zar Khan Bugti, brother Gul Khan Bugti, and son Dar Khan Bugti. The Bugti family had been targeted by Pakistani secret agencies in Afghanistan, underscoring the relentless pursuit of those who dared to stand up against injustice.

Refugee Life in Afghanistan:

Gul Bahar Bugti, like many Baloch activists, sought refuge in Afghanistan to escape persecution in their homeland. Afghanistan, a country with its own tumultuous history, became a sanctuary for those who fought for the rights of the Baloch people. The Bugti family, displaced and scattered, found solace and camaraderie among fellow refugees, forming a tight-knit community bound by a common struggle for justice.

The Martyrdom of Gul Bahar Bugti and Murad Ali Bugti:

On that fateful Sunday in Kandahar, the Bugti family faced yet another tragedy as Gul Bahar Bugti and his son Murad Ali Bugti fell victim to a ruthless attack orchestrated by motorcycle-riding assailants. The attackers, believed to be linked to Pakistani secret agencies, targeted the father and son duo in a brazen display of violence, leaving the Baloch community in shock and mourning.

The Impact on the Baloch Struggle:

Behind the headlines and geopolitical complexities, it's essential to remember the human toll of such conflicts. Gul Bahar Bugti, a father, a brother, and a grandfather, had already borne the weight of profound loss before meeting his own tragic end. Murad Ali Bugti, a son cut down in the prime of life, left behind a grieving family and community.

The Human Toll:

The martyrdom of Gul Bahar Bugti and Murad Ali Bugti sent shockwaves through the Baloch community and beyond. Their deaths highlighted the perils faced by Baloch activists, even in the supposed safety of Afghan soil. The incident underscored the need for international attention and condemnation of such extrajudicial actions by state actors.

Conclusion:

The story of Shaheed Gul Bahar Bugti and Martyr Murad Ali Bugti is a testament to the harsh realities faced by those who dare to challenge oppressive regimes. As the Baloch struggle for justice and autonomy continues, it is imperative for the international community to take notice and condemn such acts of violence. The Bugti family's journey from Balochistan to Afghanistan, marked by displacement, loss, and ultimately martyrdom, is a poignant reminder of the human cost of the pursuit of justice in conflict-ridden regions.

#shaheed gul bahar bugti#Shaheed Murad Ali Bugti#martyr#bugti#baloch#بلوچستان#بلوچ#balochistan#freedom#Afghanistan#Kandahar#dera Bugti#20دسمبر 2020#english news#Refugees#refugees afghanistan#baloch refugees#Refugees Bugti#BRP#https://www.facebook.com/ShaheedGulBaharBugti?mibextid=ZbWKwL

1 note

·

View note

Text

Remembering Shaheed Gul Bahar Bugti and Martyr Murad Ali Bugti, Baloch Refugees in Afghanistan

Introduction:

In the heart-wrenching incident that unfolded in Kandahar, Afghanistan, on Sunday, 20th December 2020, the world lost two valiant souls - Shaheed Gul Bahar Bugti and his son Martyr Murad Ali Bugti. These Baloch refugees, who had sought solace in Afghanistan, fell victim to a ruthless attack orchestrated by Pakistani secret agencies. The tragic event adds another chapter to the Bugti family's history of loss and struggle. This SEO-optimized article delves into the life of Gul Bahar Bugti, a brave and fearless Baloch nationalist, who dedicated his existence to the relentless pursuit of justice for Balochistan.

The Plight of Baloch Refugees:

User Were Shaheed Gul Bahar Bugti Baloch Refugees lived In Afghanistan, far from the land they once called home. The Bugti family's journey in Afghanistan was marked by the pursuit of peace and security, a respite from the unrest that plagued Balochistan. Unfortunately, this quest for refuge took a tragic turn when Gul Bahar Bugti and his son Murad Ali Bugti fell victim to a merciless attack. This incident has left the Baloch community in shock and mourning, as they grapple with the loss of two individuals who embodied the spirit of resilience.

A Baloch Nationalist's Struggle "Were Shaheed Gul Bahar Bugti Baloch and his son Martyr Murad Ali Bugti Refugees living In Afghanistan," echoes the profound struggle that defined Gul Bahar Bugti's life. A prominent Baloch nationalist, Gul Bhar Bugti dedicated his existence to the cause of Balochistan. His unwavering commitment to justice and his people was evident in every aspect of his life. From the moment he sought refuge in Afghanistan to the tragic events leading to his martyrdom, Gul Bahar Bugti remained a symbol of Baloch resilience.

Gul Bahar Bugti:

The Ongoing Baloch Struggle:

Gul Bhar Bugti's struggle did not unfold in isolation. "Gul Bhar Bugti Already has lost grandson Nihal Khan Bugti, nephew Zar Khan Bugti, brother Gul Khan Bugti, and Two sons Dar Khan Bugti and Murad Ali Bugti," painting a grim picture of the challenges faced by the Bugti family. The Baloch community has been at the forefront of a protracted struggle for autonomy and justice in Balochistan. The relentless persecution by Pakistani secret agencies has claimed the lives of many, leaving families shattered and communities in perpetual grief.

The Martyrdom of Gul Bahar Bugti: By Pakistani secret agency killed in Afghanistan, Gul Bahar Bugti's martyrdom adds another painful chapter to the ongoing Baloch saga. The circumstances surrounding his death are a stark reminder of the dangers faced by Baloch activists, even in foreign lands. The motorcycle ride that led to his demise symbolizes the ruthlessness with which these attacks are executed, leaving families and communities in despair.

Martyr Murad Ali Bugti: A Son's Sacrifice:

The tragedy not only claimed the life of Gul Bahar Bugti but also his son, Martyr Murad Ali Bugti. The phrase "User Were Shaheed Gul Bahar Bugti Baloch and his son Martyr Murad Ali Bugti Refugees living In Afghanistan" encapsulates the shared fate of a father and son who sought refuge together, only to face the same tragic end. Murad Ali Bugti, like his father, was dedicated to the Baloch cause, and his sacrifice deepens the wounds of a community already scarred by relentless persecution.

In remembering Shaheed Gul Bahar Bugti and Martyr Murad Ali Bugti, we pay homage to the indomitable spirit of Baloch nationalists who continue to face adversity with courage. "By Pakistani secret agency killed in Afghanistan Gul Bahar Bugti who was Struggle Baloch National and for Balochistan" reflects the broader narrative of a community's fight for justice. As we mourn the loss of these two brave souls, we must also reflect on the urgent need for international attention and support to bring an end to the plight of Baloch refugees and the ongoing struggle for justice in Balochistan.

Conclusion:

#martyr#بلوچستان#بلوچ#balochistan#bugti#shaheed gul bahar bugti#wazir khan bugti#baloch#news urdu#english news#Shaheed Zar Bahar Bugti#Shaheed Gul Khan Bugti#Shaheed Dur Khan Bugti#Shaheed Murad Ali Bugti#Shaheed Nihal Khan Bugti#Shaheed#Freedom#BRP#Baloch Republican party

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Remembering Shaheed Nihal Khan Bugti and Shaheed Zar Khan Bugti: A Decade of Remembrance

It's will be the 10th martyrdom anniversary of Shaheed Nihal Khan Bugti and Shaheed Zar Khan Bugti. They were targeted and killed by Pakistan’s intelligence agencies in Spin Boldak, #Afghanistan

As we approach the solemn occasion of the 10th martyrdom anniversary of Shaheed Nihal Khan Bugti and Shaheed Zar Khan Bugti, it's essential to reflect on the tragic events that unfolded in Spin Boldak, #Afghanistan on 15th December 2013. These brave souls, targeted and killed by Pakistan’s intelligence agencies, left an indelible mark on the lives of those who knew them.

It's will be the 10th martyrdom anniversary of Shaheed Nihal Khan Bugti and Shaheed Zar Khan Bugti. Their sacrifice serves as a stark reminder of the challenges faced by refugees in Afghanistan, struggling against adversities while seeking safety and a brighter future.

It's will be the 10th martyrdom anniversary of Shaheed Nihal Khan Bugti and Shaheed Zar Khan Bugti. The tragic incident not only impacted the Bugti family but also resonated with the broader community, sparking conversations about the safety and security of refugees in Afghanistan.

As we commemorate the 10th martyrdom anniversary of Shaheed Nihal Khan Bugti and Shaheed Zar Khan Bugti, it's crucial to advocate for justice and raise awareness about the plight of refugees in Afghanistan. The incident underscores the need for international attention to ensure the safety of those seeking refuge from conflict-ridden areas.

It's will be the 10th martyrdom anniversary of Shaheed Nihal Khan Bugti and Shaheed Zar Khan Bugti. Their memory lives on as a testament to the resilience of those who face persecution, and it's our collective responsibility to shed light on their story, fostering empathy and understanding for refugees in Afghanistan.

In conclusion, as we mark the 10th martyrdom anniversary of Shaheed Nihal Khan Bugti and Shaheed Zar Khan Bugti, let us not only remember their sacrifice but also strive towards creating a world where refugees in Afghanistan and beyond can live without fear. The poignant legacy of these brave individuals should inspire us to work towards a future where such tragedies are a thing of the past.

0 notes

Text

Shaheed Gul Bahar Bugti

#Shaheed Gul Bahar Bugti#Bugti#Baloch#Balochistan#Martyr#Afghanistan#Kandahar#FreeBalochistan#Freedom#Refugees#Bugti Refugees Afghanistan#Bugti Refugees

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

15 دسمبر شہید زر خان بگٹی اور شہید نہال خان بگٹی کی آٹھویں برسی منائی جا رہی ہے۔

#15th dec 2013 Refugees camp attacked by Paki ISI in Spin Boldak Afghanistan SHaheed Zar Khan Bugti & Shaheed Nehal Khan Bugti were martyred#Shaheed Zar Khan Bugti#and#Shaheed Nihal Khan Bugti#Refugees Spin Boldak#Afghanistan

2 notes

·

View notes