#Carlos Sahagún

Text

(...) Alrededor no había nadie: un árbol,

un estanque, ceniza en aquel monte

lejano. Alrededor no había nadie.

Pero, ¿qué es este viento, quién me coge

el corazón y lo levanta e vilo,

y lo hunde y lo levanta en vilo? Una

muchacha azul en la orfandad del aire

ordenaba los pájaros. sus manos

acariciaban con piedad el árbol,

y el estanque, y aquel lejano monte

ceniciento. El jardín ardía al sol.

La miré. Nada. La miré de nuevo,

y nada, y nada. Alrededor, la tarde.

Aquí empieza la historia | Carlos Sahagún

#Carlos Sahagún#Aquí empieza la historia#poesía#fragmento#literatura#lit#tarde#nada#jardín#sol#árbol#aire#viento#ceniza#monte#corazón#muchacha#azul#piedad#estanque#lejano

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reading List - Lista para Leer

Aves sin nido Clorinda Matto de Turner

Dom Casmurro Joaquim Maria Machado de Assis

Ariel José Enrique Rodó

El Moto Joaquin Garcia Monge

La amada inmóvil Amado Nervo

Desolación Gabriela Mistral

La señorita Etcétera Arqueles Vela

La vorágine José Eustasio Rivera

Doña Bárbara Rómulo Gallegos

Cuentos de Amor, de Locura y de Muerte Horacio Quiroga

Other selected works

Isabel Allende, “Dos palabras”

Anónimo, “Romance de la pérdida de Alhama”

Anónimo, Lazarillo de Tormes (Prólogo; Tratados 1, 2, 3, 7)

Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer, Rima LIII (“Volverán las oscuras golondrinas”)

Jorge Luis Borges, “Borges y yo”

Jorge Luis Borges, “El Sur”

Julia de Burgos, “A Julia de Burgos”

Miguel de Cervantes, Don Quijote (Primera parte, capítulos 1–5, 8 y 9; Segunda parte, capítulo 74)

Julio Cortázar, “La noche boca arriba”

Hernán Cortés, “Segunda carta de relación” (selecciones)

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, “Hombres necios que acusáis”

Rubén Darío, “A Roosevelt”

Don Juan Manuel, Conde Lucanor, Exemplo XXXV (“De lo que aconteció a un mozo que casó con una mujer muy fuerte y muy brava”)

Osvaldo Dragún, El hombre que se convirtió en perro

Carlos Fuentes, “Chac Mool”

Federico García Lorca, La casa de Bernarda Alba

Federico García Lorca, “Prendimiento de Antoñito el Camborio en el camino de Sevilla”

Gabriel García Márquez, “El ahogado más hermoso del mundo”

Gabriel García Márquez, “La siesta del martes”

Garcilaso de la Vega, Soneto XXIII (“En tanto que de rosa y azucena”)

Luis de Góngora, Soneto CLXVI (“Mientras por competir con tu cabello”)

Nicolás Guillén, “Balada de los dos abuelos”

José María Heredia, “En una tempestad”

Miguel León-Portilla, Visión de los vencidos (dos secciones: “Los presagios, según los informantes de Sahagún” y “Se ha perdido el pueblo mexica”)

Antonio Machado, “He andado muchos caminos”

José Martí, “Nuestra América”

Rosa Montero, “Como la vida misma”

Nancy Morejón, “Mujer negra”

Pablo Neruda, “Walking around”

Emilia Pardo Bazán, “Las medias rojas”

Francisco de Quevedo, Salmo XVII (“Miré los muros de la patria mía”)

Horacio Quiroga, “El hijo”

Tomás Rivera, . . . y no se lo tragó la tierra (dos capítulos: “... y no se lo tragó la tierra” y “La noche buena”)

Juan Rulfo, “No oyes ladrar los perros”

Alfonsina Storni, “Peso ancestral”

Tirso de Molina, El burlador de Sevilla y convidado de piedra

Sabine Ulibarrí, “Mi caballo mago”

Miguel de Unamuno, San Manuel Bueno, mártir

#lista para leer#catholic#feminine#reading list#Spanish reading list#spanish#reading#books to read#classic books

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vía Tlacaélel

La diosa del Tepeyac que cambiaron por una virgen 🙏🏾

“Cerca de los montes hay tres cuatro lugares donde solían hacer muy solemnes sacrificios, y que venían a ellos de muy lejanas tierras. El uno de estos es aquí en México, donde está un montecillo que se llama Tepeacac, y los españoles llaman Tepeaquilla, y ahora se llama Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe. En este lugar tenían un templo dedicado a la madre de los Dioses, que ellos la llamaban Tonantzin, que quiere decir nuestra madre.”

“Texto del padre Sahagún” Carlos María de Bustamante

No olvides seguirnos en Instagram para más contenido 👉🏽@tlacaeleloficial

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

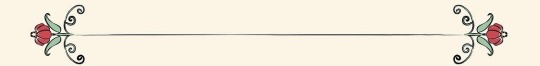

Famous 1922 births.

Bishop José De Jesús Sahagún De La Parra (Mexican Catholic bishop)

Albert Lamorisse (French movie director & producer)

Betty White Ludden (American actress)

Agathe Poschmann (German actress)

Joanne Dru Wood (American actress)

Daniel Macnee (British-American actor)

Haskell Wexler (American cinematographer & movie producer)

Audrey Meadows Six (American actress)

Kathryn Grayson (American actress & singer)

Archbishop Hilarion Capucci (Syrian Catholic archbishop)

Ralph H. Baer (German-American inventor & video game designer)

Cyd Charisse Morris (American actress & dancer)

Karl Kordesch (Austrian-American inventor)

Carl Reiner (American actor & director)

Russ Meyer (American movie director & producer)

Richard Kiley (American actor & singer)

Doris Day (American actress & singer)(pictured)

Josephine Cottle Masterson aka Gale Storm (American actress & singer)

Michael Ansara (Syrian-American actor)

Barbara Hale Katt (American actress)

Jack Klugman (American actor)

Roscoe Brown (American actor & director)

Darren McGavin (American actor)

Bea Arthur (American actress)

Sir Christopher Lee (British actor & singer)

Baroness Sheila Sim Attenborough (British actress)

Judy Garland DeVinko (American actress & singer)(pictured)

Eleanor Parker Hirsch (American actress)

Howie Schultz (American baseball & basketball player)

Jason Robards; Jr. (American sailor & actor)

Rory Calhoun (American actor)

Friar Jules Wieme (Belgian Catholic lay brother & missionary)

Margaret Middleton aka Yvonne De Carlo (Canadian-American actress)

Isaac Caesar (American actor & writer)

Jackie Cooper; Jr. (American actor & director)

Mervyn Hamilton (American movie director)

Janis Paige Gilbert (American actress & singer)

Cardinal Roger Etchegaray (French Catholic cardinal)

Noémi Ban (Hungarian-American holocaust survivor & lecturer)

Lizabeth Scott (American actress & singer)

Dr. St. Gianna Beretta Molla (Italian doctor & Catholic saint)

Fr. Luigi Giussani (Italian Catholic priest)

Coleen Gray Zeiser (American actress)

Ruby Dee Davis (American actress & poet)

Michel Galabru (French actor)

Iancu Țucărman (Romanian engineer & holocaust survivor)

Barbara Bel Geddes Lewis (American actress & artist)

Dorothy Dandridge (American actress & singer)

Kim Hunter Emmett (American actress)

Constance Ockelman aka Veronica Lake (American actress)

Stanford R. Ovshinsky (American engineer & inventor)

Charles M. Schulz (American cartoonist)

Redd Foxx (American comedian & actor)

Maila Syrjäniemi Mioni aka Maila Nurmi (American actress)

Paul Winchell (American actor & ventriloquist)

Ava Gardner (American actress)

Stan Lee (American comic book writer & editor)(pictured)

#Religion#Celebrities#Movies#TV Shows#Music#Ohio#Minnesota#U.K.#Books#Comics#New York City#New York#Mexico#France#Illinois#Germany#West Virginia#North Carolina#Syria#Italy#Video Games#New Hampshire#Texas#Austria#Oregon#Pennsylvania#New Jersey#Washington#Sports#Baseball

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Felipe and Letizia retrospective: July 19th

2004: Opening of the XV Congress of the Hispanist International Association in Monterrey, north of Mexico & Reception offered by Monterrey’s Governor Jose Natividad Gonzalez Paras

2006: Lunch offered to the president of Mexico, Vincent Fox and first lady Marta Sahagún de Fox at la Zarzuela

2007: Breitling Regatta

2010: Opening of the Army Museum in Toledo

2012: Conference on rare diseases: “The cycle of Urea and its Pathologies”

2017: Visited the Santo Toribio de Liébana Monastery, Camaleño, Cantabria. (1, 2, 3, 4).

2018: Audiences at la Zarzuela & 210th anniversary of the Bailen Battle in Bailen, Spain. (1, 2, 3)

2019: Received Miguel Ángel Revilla Roiz, president of the Comunidad Autónoma de Cantabria, at la Zarzuela; Received Alfonso Fernández Mañueco, president of the Junta de Castilla y León, at la Zarzuela & Audiences at la Zarzuela (1, 2, 3, 4)

2021: Audience with Juan José González Rivas, president of the Constitutional Court. & Audience with Carlos Lesmes Serrano, president of the Supreme Court and the General Council of the Judiciary.

F&L Through the Years: 803/??

#King Felipe#Queen Letizia#King Felipe of Spain#Queen Letizia of Spain#King Felipe VI#King Felipe VI of Spain#F&L Through the Years#July19

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

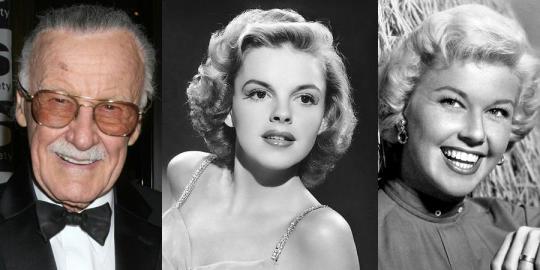

No actuaremos de forma tramposa en tema de desaparecidos: AMLO

La titular de la Comisión Nacional de Búsqueda aseguró que existen 94 mil personas desaparecidas en México.

Por Carlos Lara Moreno | Reportero

Teresa Guadalupe Reyes Sahagún, titular de la Comisión Nacional de Búsqueda (CNB), comentó que para el gobierno federal hasta el último corte existen 94 mil 283 personas desaparecidas en México.

En conferencia de prensa, Reyes Sahagún expuso que se tienen…

View On WordPress

0 notes

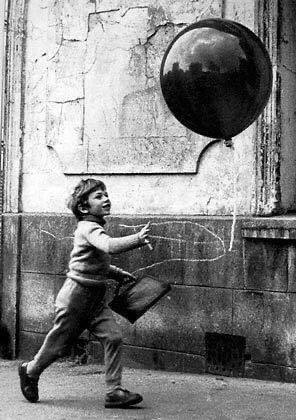

Photo

El pasado nos abre las ventanas

y penetran sus sombras con el canto.

Al niño de mi historia lo levanto

hasta la luz de todos los mañanas.

(Carlos Sahagún)

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Muchas veces me pregunto

qué hacíamos tú y yo antes de querernos.

Carlos Sahagún

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Vista de la fachada posterior, Escuela Primaria Urbana Federal Fray Bernardino de Sahagún, calle Victor Manuel Villaseñor, Centro, Ciudad Sahagún, Fray Bernardino de Sahagún, Hidalgo, México 1952

Arqs. Carlos Lazo, David Muñoz Suárez y Francisco Calderón

View of the rear facade, Federal Urban Primary School Fray Bernardino de Sahagun, calle Victor Manuel Villasenor, Centro, Ciudad Sahagun, Fran Bernardino de Sahagun, Hidalgo, Mexico 1952

#carlos lazo#david muñoz suárez#francisco calderón#ciudad sahagún#fray bernardino de sahagún#hidalgo#mexico#modernism#modern architecture#arquitectura moderna#urban planning

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

DÍAS DE GUARDAR Domingo 24 de abril de 2022

DÍAS DE GUARDAR Domingo 24 de abril de 2022

Arte: @jjolplascencia

* Washington: turismo de seguridad; Guanajuato: balas y muerte

* Alejandra Gutiérrez: caen la fachada y se vuelve tapadera

* No tener quehacer: revive Luis Ernesto Ayala a Martha Sahagún

(more…)

View On WordPress

#Alejandra Gutiérrez#Carlos Zamarripa Aguirre#Complicidad Política#Diego Sinhue Rodríguez#Héctor López Santillana Ayuntamiento#Luis Ernesto Ayala#Marta Sahagún#Opacidad#Turismo Político#Vamos México#Violencia Criminal

0 notes

Text

Como la ola de la playa, alegre

entrabas por mi corazón, lo mismo

que la ola en la playa.

"Un niño miraba el mar" / Carlos Sahagún

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

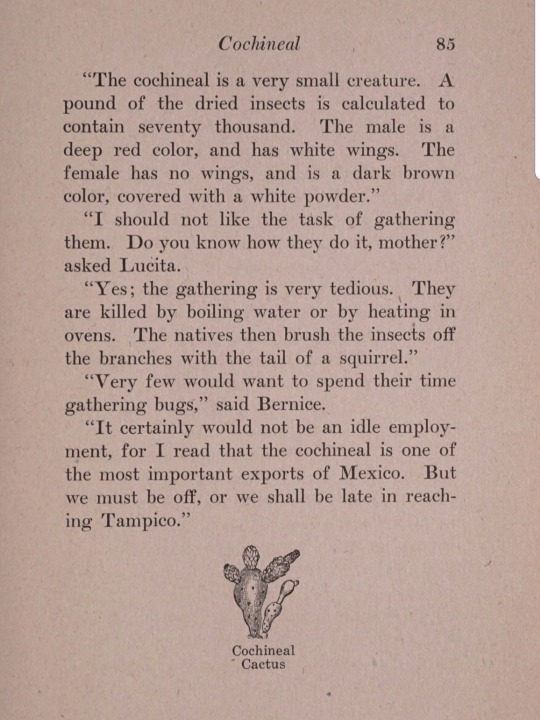

For centuries, the Indigenous cultures of present-day Mexico manufactured a brilliant red colorant called "prickly pear blood."

Nocheztli was the name the Mexica (Aztecs) gave this red colorant in their language Nahuatl. That is because in Nahuatl, the cacti were called nopalli and nochpalli, and their fruits were called nochtlí. Thus nocheztlí means blood (eztli) of the cactus (nochtlí,) or "prickly pear blood."

The colorant was actually made, however, from a parasitic insect of the prickly pear cactus, rather than the red prickly pear itself. The vivid carmine red color obtained from this insect evoked the image of blood and the juice of the red fruit.

The insect from which the dye is obtained is popularly called cochineal grana. Its scientific name is Dactylopius coccus . In Nahuatl it was called nocheztli which means "nopal blood" and in Mixtec ndukun which means "blood insect".

Both the insect and the colorant are known as cochineal.

Each pre-Hispanic indigenous culture had a different name for the insect. This ethnolinguistic element indicates the knowledge and early use of coloring by different ethnic groups before the arrival of the Spanish.

The colorant made from the cochineal insect was an astonishingly vivid red. Red was an important color for Mesoamerican cultures as it signified blood, and therefore life.

Indigenous peoples had many uses for it including as a medicine, a cosmetic, a dye for textiles, and a paint for hand-drawn manuscripts.

Mesoamerican manuscripts are important because they give insight into the people represented on them, as well as aspects of their culture. These colorful manuscripts also shed light on the expertise of the Indigenous craftspeople that made them.

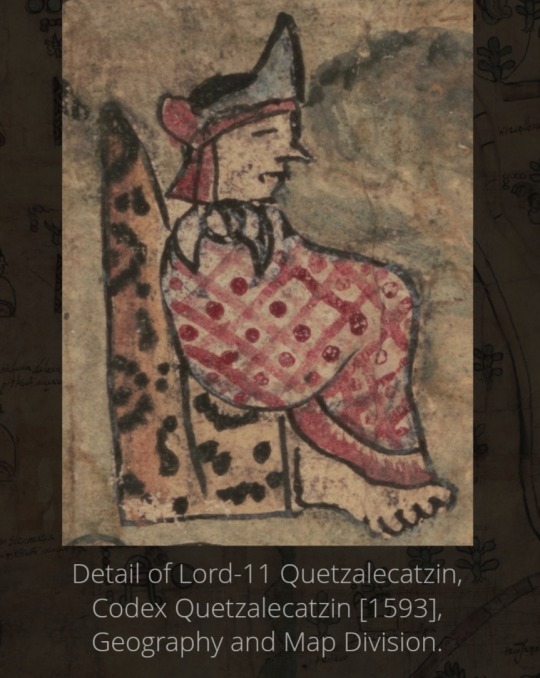

The Library of Congress has three significant 16th-century Mesoamerican manuscripts that were all painted with carmine red: the Huexotzinco Codex, the Oztoticpac Lands Map, and the Codex Quetzalecatzin.

But what do we know about cochineal?

Cultivation of Cochineal

Cochineal was primarily cultivated by individuals from cactus plots found on their lands. The production of cochineal was time-consuming and involved several steps.

First the cacti were planted and allowed to grow for up to three years in order to host the insects. After the cacti reached the appropriate size, the Indigenous farmer attached nests containing female insects to the cacti. For 90 to 120 days cochineal insects were allowed to infest the host cacti. After this period of infestation, harvesting involved removing the insects from the cacti by hand with the aid of a pointed stick or a brush. Harvesting domesticated cochineal occurred two or three times per year.

Interestingly, only female insects were harvested because the component responsible for the red dye is solely carried by wingless females. The female of this species, whose life cycle is three months, is the one that contains carminic acid, a substance that is synthesized as a dye. The insect uses this substance as a defense mechanism against predators such as ants. For its part, the male does not require this defense since its vital cycle is brief, it is reduced to a week in which it fulfills the reproductive function and then dies.

A glimpse into cochineal cultivation is provided by the French botanist Nicolas-Joseph Thiéry De Menonville who published an account of his travels in 1777 to Oaxaca to obtain, albeit illegally, the insect for France.

"On arriving at Galiatitlan, I saw a garden full of nopals, and had no doubt I should there find the precious insect I was so desirous to examine. I therefore leapt from my horse, under pretense of altering my stirrup leathers, entered the grounds of the Indian proprietor, began a conversation with him, and enquired to what use he put those plants? He answered, “to cultivate la grana.” I seemed astonished, and begged to see the cochineal; but my surprise was real when he brought it to me, for instead of the red insect I expected, there appeared one covered with a white powder. I was tormented with the doubts I entertained, and to resolve them bethought me of crushing one on white paper; and what was the result? It yielded the truly royal purple hue.”

Grana is the Spanish term for cochineal that translates as "grain," possibly because the dried cochineal insect look like grains or seeds.

What then do we know about how the brilliant carmine colorant was made from the cochineal insect?

Cochineal Colorant Preparation

Sixteenth-century sources provide eyewitness accounts of the production of Indigenous Mexican artist materials. One of the most important sources is the Florentine Codex, or The General History of the Things of New Spain, compiled by Franciscan Friar Bernardino de Sahagún. Twelve books describe the culture and peoples of central Mexico, with detailed descriptions in Spanish and Nahuatl, as well as illustrations of artists materials like cochineal.

After harvesting, the insects were then prepared for processing into a colorant. The first part of the process involved killing the cochineal insects. This was accomplished by drying in the sun, heating in ovens or on hot plates, boiling, or steaming. Regardless of the method employed, the end result of this process was dried insects.

To make a red dye or paint, the dried silver cochineal "grains" are ground into a powder that is then boiled in water. Since the cochineal is an organic colorant, its coloring agent carminic acid must be stabilized with the addition of a mordant, a metallic salt. Powdered alum (potassium aluminum sulfate) was a mordant commonly used by Mesoamerican craftspeople.

Cochineal is sensitive to changes in pH, and as such, its color can vary. Cochineal colorants can range from orange when an acid, like vinegar, is added to the recipe to purple when a base, like ammonia, is added.

The primary uses for cochineal were as a dye for textiles and as a paint. To make a paint, the cochineal insects were soaked in water, ground into a paste with alum, and formed into tablets that were allowed dry.

Tablets of cochineal paint, as well as other paints and artist materials, were made available to artisans in markets throughout Mexico. It is likely that Indigenous scribes painted the red areas on manuscripts with cochineal tablets obtained from these markets.

A large variety of items were sold in Mesoamerican markets including food, raw materials, and artist pigments. The largest market was in Tlatelolco, a neighborhood in present-day Mexico City. Descriptions of the Tlatelolco market were published by Spanish conquistadors Hernán Cortés and Bernal Díaz who were astounded by its large size and the variety of items sold there.

Markets remain an important cultural tradition in Mexico to this day.

Mesoamerican Manuscripts at the Library of Congress

The Codex Quetzalecatzin resides in the Geography and Map Division. Created circa 1593, it is a genealogy map showing the ancestral lands of Lord-11 Quetzalecatzin and his descendants, the de Leon family, between the years 1480 and 1593. It is also known as the Mapa de Ecatepec-Huitziltepec because the de Leon holdings ranged from Ecatepec (near Mexico City) to the north, to Huitziltepec in Oaxaca to the south, with southern Puebla in between.

An Indigenous scribe, or scribes, likely created the codex because it is drawn in a mostly Indigenous artistic style with pictographs that convey information relating to space and time, and toponyms (place-glyphs) relating to specific locations.

Codex Quetzalecatzin

Brilliant carmine red was liberally painted all over the Codex Quetzalecatzin.

The color red is prominently used on the garments of the Indigenous elites. A rich red decorates the borders of the noble women's blouses and skirts and the cloaks of the noble men. Not surprisingly, Lord-11 Quetzalecatzin has the most splendid garments of all with his richly patterned red cloak and headdress.

It is not surprising that red paint appears on the codex in many areas, since Puebla and Oaxaca were primary regions of cochineal cultivation during the 16th century. As nopal cacti are prominent features on the codex, it is possible that the de Leon estate produced cochineal.

The Oztoticpac Lands Map, also part of the Geography and Map Division collections, was created around 1540. It concerns the litigation of the estate of the Texcoco lords after one of their members, Don Carlos Ometochtli, was executed for idolatry. Texcoco, a neighbor to Mexico City, was a partner to the Mexica (Aztecs.) The map depicts the Palace of Oztoticpac, land plots of villagers.

Oztoticpac Lands Map

Color was sparsely used on the map, and has faded over the years. Purplish-red lines and Indigenous counting numerals (bars and dots) were used to denote the borders and size of lands owned by the Texcoco nobility.

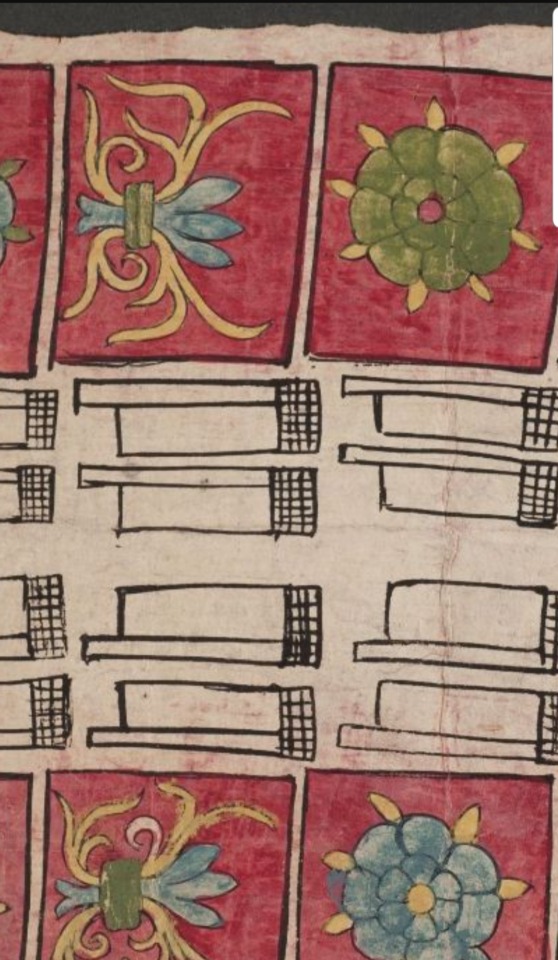

The Huexotzinco Codex is part of the Harkness Collection in the Manuscript Division. It is one of the earliest Mesoamerican manuscripts from the early colonial era of Mexico. As such, it is a thoroughly Indigenous manuscript as its story is told through pictographs showing the types of tribute items and the Indigenous counting systems.

The Huexotzinco Codex was created in 1531 for the legal case that conquistador Hernán Cortés brought against three members of the first Spanish colonial government in Mexico. The case accused the three government officials of stealing from Cortés by demanding excessive tribute from the people of Huexotzinco when he was in Spain. After the Spanish invasion, Cortés considered the land, natural resources, and the people of Huexotzinco to be his property because the Huexotzincas allied themselves with him during the war against the Mexica. Included in the court proceedings are eight Indigenous paintings submitted as evidence that depict the tribute handed over to the officials.

The eight paintings were produced by Indigenous scribes with Indigenous materials. While seven of the paintings are painted with red, vivid carmine red features prominently on two of them.

Huexotzinco, in the Mexican state of Puebla, was a major producer of cochineal in the 16th century.

Huexotzinco Codex

Painting III shows twenty cotton cloths, each richly decorated with an Indigenous calendrical pictograph (Rabbit, Reed, or Flower) representing the count of years or days. A brilliant red background offsets the pictographs. Notably red was used as the background on all of the twenty cloths and was also the most-used colorant.

Colorful, ornamented clothing of cotton and rabbit fur were reserved for the elites of Mesoamerican societies. Thus the carmine red textiles prominently featured on two codex paintings provide insight into the Huexotzinco community as well as the artisans working there.

The three Library of Congress Mesoamerican manuscripts (the Codex Quetzalecatzin, the Oztoticpac Lands Map, and the Huexotzinco Codex) have a shared history. They were created during the first century of the newly formed Spanish colony of Mexico.

Another shared aspect found on all three manuscripts is the use of carmine red paint to illuminate features that were important and specific to the people depicted on them, and to the scribes who painted them.

While visually the reds on the three Library of Congress manuscripts appear to be cochineal, to date material analysis has only confirmed the red on the Huextzinco Codex paintings to be cochineal. Hopefully future scientific analysis will also identify the reds of the Codex Quetzlecatzin and the Oztoticpac Lands Map.

While Spain profited from the production and export of cochineal, credit must be given to the Indigenous Mesoamerican peoples who developed this stunning red, this "prickly pear blood," and gave it to the world.

Once discovered by Spaniards, cochineal became one of the most valuable commodities in Europe. In 1758 alone, Oaxaca exported more than 1.5 million Spanish pounds of it for various uses, including the dying of fabrics for red uniforms worn by British soldiers. It was the most exported from New Spain during the 16th century, after gold and silver.

For centuries Europe sought an intense red that would last over time in textiles such as wool and silk. They had not found a dye with these characteristics until the discovery of cochineal. It was so prized, Spain kept secret that it came from a bug instead of a plant.

The Italian dyers of the 16th century, based in Venice and Florence, were the main buyers of dyes.

Later, in later centuries, this changed and it was the French, the Dutch and later the English who bought the scarlet, both in formal and informal trade through smuggling.

Apart from the textile industry, which is where it had its most widespread use, famous painters such as Rubens, Velázquez and El Greco, among others, also used pigments based on the cochineal grana to add unique colors in their works.

Museum conservation and restoration laboratories in different parts of the world have confirmed the presence of the dye bug in many important works.

The cochineal cochineal from New Spain produced a "boom" in European markets , says Huémac Escalona. It was the second good that generated the most profits for the people involved in its trade, both Spanish and Indian.

The Spanish crown retained the monopoly of this product throughout the colonial period; For this, it kept the secret of its nature and production, preventing the live insect from leaving New Spain. When the Spanish referred to the large cochineal they always used terms that referred to agriculture, so that competitors from other nations believed that it was a vegetable product, a fruit of a plant or a seed.

Today it can also be found as a natural food coloring.

Production of dye in Oaxaca

In the 16th century and the first part of the 17th century, the most intense production of cochineal was located in the Tlaxcala and Puebla areas. Oaxaca was the cradle of domestication of the large cochineal; it also produced in those years but not so intensely. It was not until the second half of the seventeenth century when its production increased, until it produced 99 percent of the scarlet that was exported to the entire world in the eighteenth century.

The relationship between indigenous producers and Spanish merchants around the grana was not without tensions and conflicts, despite this, the wealth it generated allowed that relationship to last over time.

The historian recalls that the indigenous communities accepted to produce the cochineal because it allowed them to have their own social organization and allowed them to have money for their festivals and to pay taxes. Although these were impositions of the colonial regime, these burdens were assumed in such a way as to allow them to have an organizational structure according to their traditions.

The rearing of the insect was an economic activity in which the whole family participated and could be combined with other tasks. The production and trade of grana articulated the economy of various regions of Oaxaca. There were towns that specialized in grana, others combined its production with the manufacture of blankets or the cultivation of corn and wheat. While others were dedicated to making the various containers where the dye was transported.

Most of the indigenous peoples, for their part, became producers of the dye because it meant a more or less secure way of obtaining resources to cover their community expenses and cover tax burdens. This was not exempt from the enrichment of sectors of its population. However, it was not the norm but rather the exception.

Grana connected the economy of societies so different and so far away : Indigenous peoples from the Oaxacan regions with European, African and Asian societies. For the Oaxacan indigenous people, the scarlet was the product that gave them benefits but also caused them discomfort. The constant international demand for dye led to the adaptation of their collective life, governed by a set of beliefs and traditions of their own, to an intense production system.

The traces of the scarlet in Oaxaca are everywhere: in civil and religious public buildings, in merchants' houses, in textiles, in its archaeological remains, in pre-Hispanic and colonial documents, painted with pigments made from the cochineal or where its production and trade were registered. It shows the importance that the precious dyeing insect known as grana cochineal had for the history of Oaxaca and Mexico.

A red color, really Mexican?

In recent years, there has been a debate about the American zone of origin of the dye . A group of scholars assured that the cochineal was domesticated in South America, in the Andean area, due to the discovery of textiles dyed with this dye in various archaeological sites and whose dating dates back to the first centuries after Christ.

Other specialists affirmed that it was in Mesoamerica, specifically in Oaxaca, where the first domestication of the insect was carried out together with the nopal. It is believed that it passed from Mesoamerica to Central America and from there to South America through the cabotage trade.

Recently, a scientific study was carried out that analyzed the mitochondrial DNA of the cochineal cochineal samples from Oaxaca and Peru. The results showed that the genetic variety from Oaxaca is older and more diverse. This confirms that the domesticated dyeing insect is native to the Mesoamerican region corresponding to the current state of Oaxaca, in southern Mexico.

Sources: (×) (×) (×)

#indigenous#mexico#aztec#france#Nicolas-Joseph Thiéry De Menonville#animal#insect#spain#europe#hernan cortes#🇲🇽#italy#dutch#new spain#history#mexican history#oaxaca#puebla#oaxaca mexico#puebla mexico#long post#asia#africa#south america#central america#latin america#peru#nahuatl

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

QUE NO SE ACABE ESA RAZA, DE LOS HOMBRES DE A CABALLO/ IMÁGENES DE AGUASCALIENTES

QUE NO SE ACABE ESA RAZA, DE LOS HOMBRES DE A CABALLO/ IMÁGENES DE AGUASCALIENTES

23/01/2022

Carlos Reyes Sahagún

A propósito del campeonato y congreso charro que se realizó en esta ciudad hace un par de meses, y a manera de conclusión, me queda la impresión de que más temprano que tarde se modificará la charrería, o mejor dicho, la serie de prácticas que conforman la charreada, en función de eliminar el maltrato a los animales, presente en varias de las suertes.

Por…

View On WordPress

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

EL FRAUDE DE GUADALUPE...

Desenmascarar el mito de la Virgen de Guadalupe es fácil, porque al igual que como sucede con el mito del cristiano, ningún historiador de esa época habla sobre los hechos milagrosos que debieron de ser de suma importancia.

El propio Fray Juan de Zumárraga, principal y supuesto testigo presencial no escribe sobre éste acontecimiento. Entre los cronistas más importantes se encuentran Bernal Díaz del Castillo, Diego de Durán, Bernandino de Sahagún, Jerónimo de Mendieta y el propio Fray Toribio de Benavente mejor conocido como Motolinía, considerado como el cronista más relevante durante la conquista de México.

Motolinía legó un compendio de crónicas que se conocen como “Historias de los Indios de la Nueva España”, obra muy valiosa porque en sus escritos documenta, con amplio detalle, los acontecimientos coloniales en esos años.

Su crónica narra la vida de los indígenas, tradiciones, ritos, organización política y social. De cómo la jerarquía católica, mediante la brutalidad perseverante y sin medida, erradicaron los cultos indígenas. Sin embargo, no menciona una sola palabra sobre Juan Diego ni de la Virgen a pesar de que vivió en el Valle de México entre 1524 y 1569, tiempo que abarca la fecha en que supuestamente sucedió la aparición, el 12 de diciembre de 1531. Motolinía tuvo 38 años para enterarse del milagro que sucedió donde él vivía y la gente con quien trabajaba, pero misteriosamente nunca escuchó sobre la virgen.

Es bueno remarcar también que Fray Juan de Zumárraga ni siquiera estaba en México durante el tiempo de la presuntas apariciones. Fue llamado para que regresara a Europa por el Rey de España Carlos V a mediados de 1531, donde permaneció y no regresó hasta 1534. Y no solo eso, Zumárraga no fue declarado obispo de México hasta 1532, es decir, no pudo haber sido testigo presencial de los hechos.

Ahora prosigamos con los estudios antropológicos e históricos. La diosa Cihuacóatl, llamada también Coatlicue y Tonantzin, que quiere decir “nuestra madrecita”, era la deidad femenina más importante venerada por los aztecas. Tenían sus altares en la cúspide del cerro de Tepeyac y el día de la fiesta era justo el día 12 de diciembre.

Bernardino de Sahagún narra en sus crónicas que los indígenas venían desde muchas partes y de muy lejos al Valle de México para rendirle culto. La fiesta iniciaba con varios días de danzas y al octavo día se trasladaban bailando al son del teponaztli. Los ministros de los ídolos llevaban a una mujer elegida veinte días antes, conocida con el nombre de Xilonen, símbolo del maíz y del poder de fecundación, quien estaba destinada a ser sacrificada en las fiestas.

Durante la evangelización con el fin de sustituir esta deidad y parar los sacrificios humanos pero sobre todo imponer a su dios blanco, los frailes buscaron que Tonantzin tuviera semejanzas con diferentes Vírgenes como la de la Natividad, María y Concepción. Agregaron vestimentas y rasgos indígenas, como el tono de piel. Derribaron sus Teocallis y en su lugar construyeron una pequeña ermita con la imagen de una virgen pintada por el indio Marcos Cipac de Aquino. En síntesis, el culto a la virgen de Guadalupe es el resultado sincrético entre dos deidades de diferentes religiones y lugares geográficos, una europea y otra azteca.

Éste culto estuvo abandonado y no fue hasta que en 1648, 117 años después de su supuesta aparición milagrosa, fue revivido por el sacerdote franciscano español Miguel Sánchez con el objetivo de atraer creyentes a la capital que era la meca del culto. Y por supuesto, todo el dinero ingresaba en los templos de la virgen de Zapopan y de San Juan de los Lagos, ubicados en la Nueva Galicia, actualmente Jalisco.

Lo demás es historia. Hoy día la virgen de Guadalupe sigue atrayendo miles de peregrinos que siguen creyendo ciegamente en la supuesta veracidad de sus apariciones. Para quienes sabemos la verdad histórica es otro mito que sirve para mantener engañado al pueblo con fines y propósitos que van, desde lo monetario, hasta la manipulación socio-política.

Así que, la próxima vez que le reces a la virgen de Guadalupe, en vez de decir Señora de Guadalupe Patrona de México y Emperatriz de las Américas, Madre Santísima de Jesús, deberías decir:

Tonanzin madre de la tierra que riges la muerte desde tu teocalli del Tepeyacatl.

¡¡Lo increíble es que aún en pleno siglo 21 se sigan arrastrando como gusanos y adorando un fraude!!

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Tláloc es una deidad mesoamericana del agua celeste. El nombre deriva de tlālli («tierra») y octli («néctar»), es decir: «el néctar de la tierra». Los mexicas lo tenían como el responsable de la estación lluviosa y hacían ceremonias para honrarlo en el primer mes del año (ātl cāhualo). Bernardino de Sahagún y Alfredo Chavero lo describen como el dios del rayo, de la lluvia y de los terremotos.

Fue una de las divinidades más antiguas y veneradas de toda Mesoamérica. Su culto se extendió por gran parte del territorio centroamericano. Fue tomado por los nómadas aztecas (así se llamaban los mexicas cuando apenas acababan de salir de Aztlán) que se instalaron en el lago Texcoco, asimilándolo como divinidad agrícola. Siguió siendo uno de los dioses fundamentales de las distintas comunidades agrícolas autóctonas; originario de la cultura de Teotihuacan, dada la caída de la ciudad pasó a Tula, y de ahí su culto se esparció entre los pueblos nahuas. Los teotihuacanos tuvieron contacto con los mayas, de ahí que ellos lo adoptaran o lo identificaran en la forma del Dios Chaac. En la cosmología tlaxcalteca, Tláloc se casó primero con Xochiquétzal, Diosa de la belleza, pero Tezcatlipoca la secuestró. Tláloc se casó otra vez con Matlalcueye, y tiene una hija o hermana mayor que es llamada Huixtocíhuatl.

Como las divinidades mesoamericanas en general, posee una ambigüedad, en cuanto a que Es una Fuerza Suprema en y de la naturaleza (la naturaleza y el cosmos no representan en los términos humanos bondad o maldad, sino más bien un entramado de fuerzas, a veces en equilibrio, a veces en pugna; en ocasiones benéficas para los humanos, otras tantas desastrosas); lo cual implica que, si bien es Dador de Vida, Providencia y Benefactor, también muestra su faceta destructiva y aniquiladora. Así desciende desde el cielo para fecundar la Tierra y poder cultivar la milpa, para germinar las semillas. Así también envía "los relámpagos y rayos, las tempestades del agua y los peligros de los ríos y del mar"; dicho en palabras del fraile de Sahagún. Dominaba también las fuerzas destructoras y si así era su voluntad podía enviar granizos, inundaciones, sequías, heladas y rayos fulgurantes o fulminantes.

Estaba encargado de enviar el agua a la comunidad a través de sus ayudantes, los tlaloques; Tláloc mismo multiplicado y diversificado, manifestado a los humanos como "seres enanos y antropomórficos" -como refiere Juan Carlos Pérez Guerrero-, que desde el interior de los cerros enviaban las cuatro clases de lluvias. Ellos también recibían súplicas y en su honor se realizaban ceremonias y rituales. Alain Musset asevera que, en vez de enanos, son la representación de las montañas que rodean el Valle de México y sobre las cuales parecen formarse las nubes que anuncian la lluvia. Su papel consistía en favorecer la venida de las aguas celestes pero también protegían a los pescadores y los navegantes.

Tláloc fue uno de los más importantes en el altiplano de México, uno de los más representados y quizás también uno de los de mayor antigüedad del panteón de Mesoamérica. Aparece representado desde la época teotihuacana. Se le manifestaba siempre con unos atributos característicos:

Anteojeras formadas por unas serpientes que se entrelazaban y cuyos colmillos acababan siendo las fauces del dios.

Una especie de bigotera que no era otra cosa que su labio superior. Se cree que este gran labio era el símbolo de la entrada en la cueva que comunica con el inframundo y que deriva de la boca de las figuras olmecas.

La cara estaba casi siempre pintada de color negro o azul, más veces de color verde, para imitar los visos que hace el agua.

Llevaba en la mano una especie de estandarte de oro, largo y con forma de culebra, terminado en punta aguda; era para representar los relámpagos y los truenos que acompañan a veces al agua de lluvia.

En los dibujos de los códices puede verse que sus vestidos tienen pintados unas manchas que son el símbolo de las gotas de agua.

Tláloc está compuesto en sus representaciones por los tlaloques o dioses de los 4 rumbos. Cada uno de ellos manejaba y era el responsable de una vasija colocada en un rumbo. Cada vasija proporcionaba una lluvia diferente.

La residencia de Tláloc era múltiple debido a la posibilidad de división de la sustancia que lo conformaba, característica que trataremos al hablar de los tlaloques. Su morada se encontraba tanto en el Templo Mayor de Tenochtitlan, como en el Tlálocán, en el interior del cerro que lleva su nombre, el cual pertenece a la cadena montañosa Tlalocan, que separa el Valle de México del de Huexotzinco. Esto no es más que en hablando en términos Eliadianos sublimación de la Paradoja de lo sagrado y lo profano. La libertad y poder absoluto que posee la Divinidad le permite tomar cualquier forma, así como estar presente en cualquiera partes, y viendo la "Morada divina" como una extensión de la misma divinidad, con aquella sucede lo mismo.

El lugar conocido como el paraíso de Tláloc se llama Tlalocán y está situado en la región oriental del Universo. De este lugar procedía el agua beneficiosa y necesaria para la vida en la tierra. Las personas que morían ahogadas o por hidropesía iban a morar a este paraíso. También acogía a los que morían de la enfermedad de la lepra. Se trata de un enclave placentero, donde pueden verse toda clase de árboles frutales, así como maíz, chía (semilla de una especie de salvia que se usa en México como refresco), frijoles y más productos. La vida allí era enteramente feliz. Conocemos la descripción de esta morada del dios gracias a los escritos hechos por el padre Bernardino de Sahagún y otros personajes, que lo oyeron de boca de los indígenas. Algunos siglos después, se descubrió en Teotihuacan un mural en que se veía representada punto por punto esta descripción. Así se pudo conocer de manera gráfica lo que ya se conocía a través de lo escrito.

Fuente: Wikipedia.org

3 notes

·

View notes

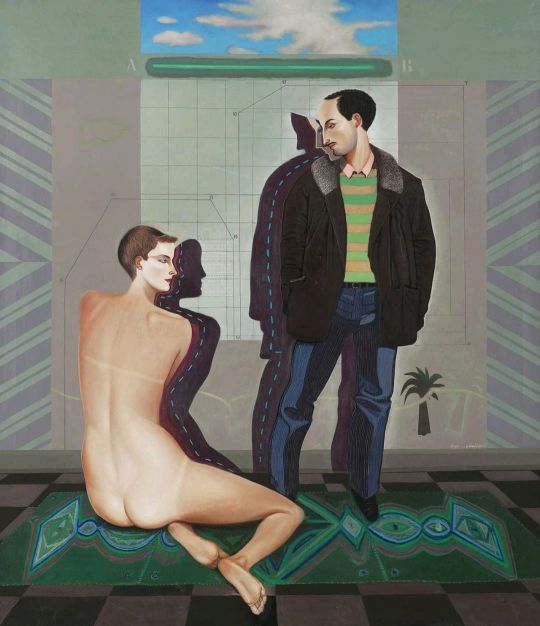

Photo

(...) Yo quería haber escrito esta última página sobre el invierno y los días de los pequeños sueños y los besos marchitos. O sobre los colores graves de los finales de estas tardes. O sobre los finos cielos de telaraña y ceniza de perla, de ese poeta que todo el mundo tiene en el olvido y a mí me gusta tanto. O sobre nombres alados de mujer, como los copos de nieve, posándose en el pelo y por encima de los hombros como lenguas de Pentecostés. Voy acabando. Deshaciendo mi pequeño refugio, estos libros que me han acompañado estos meses. No sé si cité algún verso de esos poemas de Justo Navarro tan adecuados para las luces de días más cálidos, Luciérnaga y Muerte en mitad de la primavera. Ni aquellos otros de Carlos Sahagún: «Inútil como las palabras./ Necesario como la vida». Quería escribir estas últimas líneas el día 27. Leí en Una leve exageración, de Adam Zagajewski: "El 27 de enero nació Mozart. El 27 de enero los soldados rusos entraron en el campo de concentración de Auschwitz". Y despedirme con los adioses del poema de Andrade, que comienza con una perezosa y fina niebla entre los ojos y el río. O con esa reflexión de Cernuda en Ocnos: "Llega un momento en la vida cuando el tiempo nos alcanza".⠀ ⠀ Avelino Fierro⠀ Llega un momento en la vida cuando el tiempo nos alcanza⠀ & Gonzalo Cienfuegos (artist)⠀ ⠀ ⠀ #portraitart #portraitpainting #oilpaint #oilpainting #oilpainter #oilpaintings #oilpaints #oilportrait #oiloncanvas #oilpaintingart #oilfeature #contemporaryart #contemporaryartist #contemporarypainting #contemporarypainter #contemporarypaintings #newcontemporary #modernart #modernpainting #artgallery #contemporaryartgallery #figurative #figurativeart #figurativepainting #figurativeoilpainting #figurativeportrait #undergroundart #vagabondwho #marcopolorules https://www.instagram.com/p/B9wMrPNIK8i/?igshid=p0shrslwcwx7

#portraitart#portraitpainting#oilpaint#oilpainting#oilpainter#oilpaintings#oilpaints#oilportrait#oiloncanvas#oilpaintingart#oilfeature#contemporaryart#contemporaryartist#contemporarypainting#contemporarypainter#contemporarypaintings#newcontemporary#modernart#modernpainting#artgallery#contemporaryartgallery#figurative#figurativeart#figurativepainting#figurativeoilpainting#figurativeportrait#undergroundart#vagabondwho#marcopolorules

2 notes

·

View notes