#Congo Gorilla Forest

Text

Today is The World Gorilla Day.

A Symbol of Grace and Strength.

Congo Gorilla Forest - Bronx Zoo

#And someday we'll look back and say it was fun#World Gorilla Day#Congo Gorilla Forest#Bronx Zoo#Bronx Zoo Gorillas#Wildlife#Gorilla#WorldGorillaDay#Bronx#Zoo#New York City#New York

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Nouabalé-Ndoki National Park in Brazzaville, Republic of Congo has a lot to celebrate.

The park, which celebrated its 30th anniversary on December 31 of 2023, also shared an exciting conservation milestone: 2023 was the first year without any elephant poaching detected.

“We didn’t detect any elephants killed in the Park this year, a first for the Park since [we] began collecting data. This success comes after nearly a decade of concerted efforts to protect forest elephants from armed poaching in the Park,” Ben Evans, the Park’s management unit director, said in a press release.

Nouabalé-Ndoki National Park was developed by the government of Congo in 1993 to maintain biodiversity conservation in the region, and since 2014, has been cared for through a public-private partnership between Congo’s Ministry of Forest Economy and the Wildlife Conservation Society.

Pictured: Nouabalé-Ndoki National Park. Photo courtesy of Scott Ramsay/Wildlife Conservation Society

Evans credits the ongoing collaboration with this milestone, as the MEF and WCS have helped address escalating threats to wildlife in the region.

This specifically includes investments in the ranger force, which has increased training and self-defense capabilities, making the force more effective in upholding the law — and the rights of humans and animals.

“Thanks to the strengthening of our anti-poaching teams and new communication technologies, we have been able to reduce poaching considerably,” Max Mviri, a park warden for the Congolese government, said in a video for the Park’s anniversary.

“Today, we have more than 90 eco-guards, all of whom have received extensive training and undergo refresher courses,” Mviri continued. “What makes a difference is that 90% of our eco-guards come from villages close to the Park. This gives them extra motivation, as they are protecting their forest.”

As other threats such as logging and road infrastructure development impact the area’s wildlife, the Park’s partnerships with local communities and Indigenous populations in the neighboring villages of Bomassa and Makao are increasingly vital.

“We’ve seen great changes, great progress. We’ve seen the abundance of elephants, large mammals in the village,” Gabriel Mobolambi, chief of Bomassa village, said in the same video. “And also on our side, we benefit from conservation.”

Coinciding with the Park’s anniversary is the roll-out of a tourism-focused website, aiming to generate 15% of its revenue from visitors, which contributes significantly to the local economy...

Nouabalé-Ndoki also recently became the world’s first certified Gorilla Friendly National Park, ensuring best practices are in place for all gorilla-related operations, from tourism to research.

But gorillas and elephants — of which there are over 2,000 and 3,000, respectively — aren’t the only species visitors can admire in the 4,334-square-kilometer protected area.

The Park is also home to large populations of mammals such as chimpanzees and bongos, as well as a diverse range of reptiles, birds, and insects. For the flora fans, Nouabalé-Ndoki also boasts a century-old mahogany tree, and a massive forest of large-diameter trees.

Beyond the beauty of the Park, these tourism opportunities pave the way for major developments for local communities.

“The Park has created long-term jobs, which are rare in the region, and has brought substantial benefits to neighboring communities. Tourism is also emerging as a promising avenue for economic growth,” Mobolambi, the chief of Bomassa village, said in a press release.

The Park and its partners also work to provide education, health centers, agricultural opportunities, and access to clean water, as well, helping to create a safe environment for the people who share the land with these protected animals.

In fact, the Makao and Bomassa health centers receive up to 250 patients a month, and Nouabalé-Ndoki provides continuous access to primary education for nearly 300 students in neighboring villages.

It is this intersectional approach that maintains a mutual respect between humans and wildlife and encourages the investment in conservation programs, which lead to successes like 2023’s poaching-free milestone...

Evans, of the Park’s management, added in the anniversary video: “Thanks to the trust that has been built up between all those involved in conservation, we know that Nouabalé-Ndoki will remain a crucial refuge for wildlife for the generations to come.”"

-via Good Good Good, February 15, 2024

#conservation#congo#republic of congo#elephant#gorilla#endangered species#biodiversity#conservation news#conservation efforts#indigenous communities#national park#protected areas#poaching#elephant poaching#ecology#biology#environment#environmental news#forests

957 notes

·

View notes

Text

DR Congo 🇨🇩

Facts about DR Congo, the richest Country with Natural Resources in the world 🇨🇩

1. Music is its biggest export

2. Kinshasa is world's second largest French speaking city.

3. Locals eat mayo with everything

4. Kinshasha and Brazaville are the world's closest capitals.

5. The Wildlife is Phenomenal

6. The Congo isn't overrun by the Ebola Virus

7. Congo played a role in World War II

8. DRC is one of the Countries in East and Central Africa where one can find the Mountain Gorillas and the Eastern Lowland Gorillas.

9. The Democratic Republic of the Congo is the second largest country in Africa. It borders nine countries: Angola, Burundi, the Central African Republic, the Republic of Congo, Rwanda, South Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zambia.

10. The people of the DRC represent over 200 ethnic groups, with nearly 250 languages and dialects spoken throughout the Country.

11. DRC has more than 450 tribes , one of biggest hydro dam in the world, the biggest stock of water, second large river in the world, second biggest forest after amazonia, has the oldest and biggest park in Africa( virunga), is the only one country in the world with okapi animal, biggest world s minerals's stuff: copper, lithium, cobalt, gold, coltan, cassiterite, nobium, gold, diamond, uranium.., one of the peaceful and kind population in the world, hiroshima & Nagasaki nuclear bomb were made by uranium from the south EST of DRC, has the second biggest island in africa( Idjwi, island) second deepest lake in the world after baikal lake in Russia, 12 national parks with all types of wild animals,. and so on

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Video description under the cut because it is lengthy!

[video description. Video is a tiktok by user@zooatl. The video shows several video clips and white text over the images. The video starts of with an image of two adult male gorillas in a large grassy enclosure while they graze on vegetation and text reads, "do you know about the connection between gorillas and cell phones?". Next, an image of a dark mineral on a white black ground and text reads "the mineral coltan is a cristal component to cell phones and other small electronics." Next, a video clip of many people working in a dirt pit, or mine and text reads, "coltan is mined primarily in the forests of the eastern Congo". Next, video clip shows a very young male gorilla in the foreground of a grassy enclosure, with several adults in the background text reads "... In the middle of habitats native to gorillas like Floyd" Next clip features an adult male sitting on a rock eating from a metal puzzle, "luckily, a number of organizations are working together with ECO-CELL to make cell phone recycling easier!"

The next image features an infographic titled "Zoo Atlanta recycling program" the infographic is a circle half of which is blue and labeled and the other half is green and text reads where the colors meet "the gorilla connection when you recycle" with arrows pointing in both directions to indicate the flow of the infographic. The circle features illustrated images of a cell phone leading to a mineral clump (coltan) with a pickaxe pointing to a circle on a map of Africa with the image of gorillas in the circle. The blue half shows a cellphone with the recycle symbol behind it then an image of a world map with arrows from the USA to multiple other continents, then an image of paper money stacked up, an image of a poster of a gorilla with flames around it, binoculars, and the silhouette of an adult gorilla. Blocks of text around the central circle image reads, "Zoo Atlanta and the Diane Fossey Gorilla Fund International are working together with ECO-CELL to recycle cell phones, help the environment and raise money to help gorilla conservation. Coltan is a critical component to cell phones and small electronics. One of the few places in the world that coltan is found is the Democratic Republic of the Congo- right in the middle of gorilla habitat. As a result of minding for coltan, critical habitat has been destroyed and gorillas have been displaced. The reuse of cell phones results in the need for fewer new ones, which in turn reduces the need for coltan mining. Most cell phones will be refurbished and resold to first time lower income users in areas outside the US. Donations to the Diane Fossey Gorilla Fund International will help further their work to protect gorillas."

A short video clip of first person view walking into a building labeled Gorilla Conservation Center where there is a bin to donate cellphones with the image of a young gorilla on it. Text reads "you can donate your cell phone right here at Zoo Atlanta - and enjoy an up close look at the gorillas while you're at it!" A clip of male gorillas in a large grassy enclosure plays.

While this video plays, an upbeat electric guitar song plays. End video description.]

432 notes

·

View notes

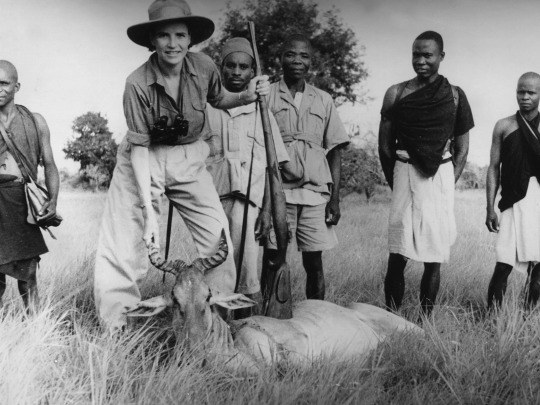

Photo

#MonochromeMonday Shout out from our friends @theoriginalkerdowney Guide Spotlight: Tony Binks As a son of a Ker & Downey director & guide, Tony caught the 'safari bug' at an early age. His lifelong apprenticeship tagging along with his father's wilderness adventures, other guides' safaris, and later his own; means he has gained a deep knowledge and passion for the wilderness, the flora & fauna and the tribal people & cultures that inhabit Africa’s wilder places. Tony has guided guests and visited many, if not most of sub-Saharan Africa’s parks and wild spaces, from trekking gorillas in the Congo forests to tracking lion on foot in the Namib desert, from diving with migrating humpback whales in the Indian Ocean to driving amongst an endless sea of a million migrating wildebeest in the Mara-Serengeti. There are so many amazing, life-changing moments, experiences and scenes to behold in Africa you could fill several lifetimes and still have much to see. To book your safari with K&D, please visit our website www.kerdowneysafaris.com ___________ Photo by K&D Associate Guide @oliver.nicklin #Wildography #africansafaris #conservation #wild #wildlife #africa #kerdowney #safari #adventure #adventuretravel #exploringafrica #photographicsafari #specialistphotosafaris #wildphotosafaris #wildlifephotography #africanphotosafaris #africatravel #luxurysafari #ourplanetdaily #earthonlocation #kenyamoore https://www.instagram.com/p/CqBlA26sfCv/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#monochromemonday#wildography#africansafaris#conservation#wild#wildlife#africa#kerdowney#safari#adventure#adventuretravel#exploringafrica#photographicsafari#specialistphotosafaris#wildphotosafaris#wildlifephotography#africanphotosafaris#africatravel#luxurysafari#ourplanetdaily#earthonlocation#kenyamoore

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

29.12.2023 | Petitions for the environment and climate change.

Please read, share wherever you can, talk about them and if you can afford it, please, please, please donate - consider taking up a collection among your friends.

Actions.eko.com: Nestlé and P&G: Stop setting Indonesia’s rainforests on fire

Indonesia’s forests are burning – a thick toxic haze suffocates half of the country, keeping children out of school and forcing people and animals to relocate. But it didn’t happen by accident and we know who the arsonists are. Together, we will hold them accountable.

Nestlé and Procter & Gamble are doing business with rogue palm oil and paper producers who recklessly burn precious rainforests to the ground to expand their monocultures, steal Indigenous lands, and drive orangutans, rhinos, and elephants closer to the brink of extinction. (keep reading)

Rainforest Action Network - RAN: This one is for donating, they need 100,00$ by December 31!

We urgently need your help to fight for the world's last rainforests in 2024 by making any size donation today. Those who believe they can change the world are the ones that do. Donate now.

Help us challenge mega-corporations like Liberty Mutual, Bank of America, Procter & Gamble, Nestlé and Mondelēz. Their thirst for endless profits contributes to the widespread destruction of irreplaceable rainforests like the Leuser Ecosystem of North Sumatra and the Amazon rainforest and fuels the expansion of dangerous fossil fuel projects that choke the life out of the planet.

For a small organization, RAN's significant impact is only possible because of dedicated supporters like YOU. Your generous donation today makes a world of difference.

Rainforest Rescue: DRC: Do not sacrifice Congo's rainforests to the oil industry!

The DRC government in Kinshasa is nearing a point of no return: President Tshisekedi wants to sacrifice vast areas of Congo rainforest and peatland for oil. This would be an unmitigated disaster for the climate, biodiversity and local people. Together with our African partner organizations, we can put a stop to these plans.

The rainforests of the Congo Basin are home to millions of people and countless animal and plant species, including chimpanzees, bonobos and gorillas. They are a treasure trove of biodiversity and crucial to the fight against climate change.

Despite this, the government of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) began auctioning 27 oil and 3 gas blocks in late July. The blocks cover some of the last remaining intact forests on Earth.

Three of the blocks overlap the Cuvette Centrale peatlands, which are estimated to store 30 billion tons of carbon, the equivalent to one years’ worth of global emissions. The peatlands are so vast and remote that little is known about the biodiversity at stake there. Nine oil blocks overlap protected areas.

More than half of the Congo Basin's peatlands and 60 percent of its rainforest are in the DRC, the country plays a key role in the fight against the climate crisis.

The science is clear: the governments of the world must cut carbon emissions in half within the next eight years.

In his speech at the UN's COP26 conference in Glasgow, President Tshisekedi promoted the vital role of the Congo Basin forests in regulating the global climate and his intention to enhance DRC’s energy mix by "combining several types of energy: biomass, hydro, solar." The cost of not doing so, he said, would be a climate crisis.

The world cannot afford any further expansion of oil and gas. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), an immediate end to new investment in fossil fuel supply projects is the first step to keep global warming below 1.5°C and achieve global net zero emissions by 2050.

In an alliance of environmentalists from Africa and around the world, we want to keep the oil in the ground and the fossil fuel industry out of the Congo Basin. Please sign our joint petition!

DR Congo: Stop the destruction by miners and loggers in Tshopo!

The Democratic Republic of the Congo is home to the second largest area of rainforest on Earth. Defending it is crucial to the fight against climate change and the extinction crisis. Yet miners are polluting rivers and loggers clearing forests in Tshopo province. In the small town of Basoko, local people are fighting back.

The people of the small town of Basoko fear for their health and livelihoods: the Aruwimi River, a tributary of the Congo, has been polluted ever since the Chinese mining company Xiang Jiang Mining began dredging for gold there. Some species of fish have disappeared completely. Skin diseases are on the rise.

"We say NO to mining in Aruwimi, which is destroying our ecosystem in an anarchic way," states a memorandum to the county government read during a demonstration. On March 11, 2022, residents of the region protested on land and with boats against the trashing of their environment.

Mining is not the only threat to nature in Tshopo province: companies such as FODECO, Congo Futur and SOFORMA are reportedly logging at a breakneck pace near Basoko.

"They are systematically plundering the forests without any benefit to local people," says Jean-François Mombia Atuku, chairman of the environmental protection organization RIAO-RDC. "Anyone who demands accountability is silenced," he said, adding that workers are "kept like slaves" in the forest. "Human rights are not relevant for these companies."

The grievances regarding mining have been heard in the capital Kinshasa: In January 2022, Environment Minister Eve Bazaiba called on Xiang Jiang Mining to cease operations by February 25, 2022. However, nothing has changed since then – the company is still operating, apparently unimpressed.

"What we need now is international pressure," says Jean-François Mombia Atuku. It must be brought to bear on President Tshisekedi, who positioned his country as a heavyweight in the fight against the climate crisis during the COP26 climate conference.

It’s time to apply that international pressure – please sign our petition.

#long post#signal boost#environment#climate change#rainforests#Indonesia#Congo#Democratic Republic of Congo#donations#petitions#climate crisis#mining#Congo Basin#COP26#Glasgow COP26#defending the Earth#defending the planet#animal extinction#animal conservation#forest conservation#nature conservation#my posts

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

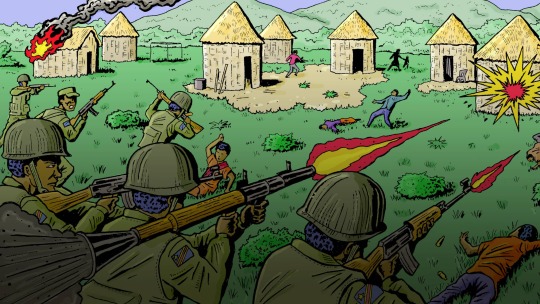

How the world’s favorite conservation model was built on colonial violence | Grist

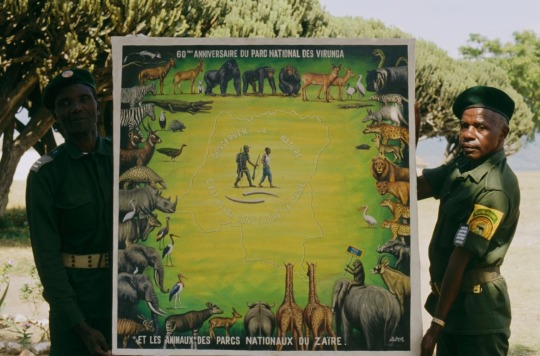

On a 1919 trip to the United States, King Albert I of Belgium visited three of the country’s national parks: Yellowstone, Yosemite, and the newly established Grand Canyon. The parks represented a model developed by the U.S. of creating protected national parks, where visitors and scientists could come to admire spectacular, unchanging natural beauty and wildlife. Impressed by the parks, King Albert created his own just a few years later: Albert National Park in the Belgian Congo, established in 1925.

Widely seen as the first national park in Africa, Albert National Park (now called Virunga National Park), was designed to be a place for scientific exploration and discovery, particularly around mountain gorillas. It also set the tone for decades of colonial protected parks in Africa. Although Belgian authorities claimed that the park was home to only a small group of Indigenous people — “300 or so, whom we like to preserve” — they violently expelled thousands of other Indigenous people from the area. The few hundred selected to remain in the park were seen as a valuable addition to the park’s wildlife rather than as actual people.

And so modern conservation in Africa began by separating nature from the people who lived in it. Since then, as the model has spread across the globe, inhabited protected areas have routinely led to the eviction of Indigenous peoples. Today, these conservation projects are led not by colonial governments but by nonprofit executives, large corporations, academics, and world leaders.

For much of human history, most people lived in rural areas, surrounded by nature and farmland. That all changed with the Industrial Revolution. By the end of the 19th century, European forests were vanishing, cities were growing, and Europeans felt increasingly disconnected from the natural world.

“With industrialization, the link with the natural cycle of things got lost — and that also led to a certain type of romanticization of nature, and a longing for a particular type of nature,” said Bram Büscher, a sociologist at Wageningen University in the Netherlands.

In Africa, Europeans could experience that pure, untouched nature, even if it meant expelling the people living on it.

“The idea that land is best preserved when it’s protected away from humans is an imperialist ideology that has been imposed on Africans and other Indigenous people,” said Aby Sène-Harper, an environmental social scientist at Clemson University in South Carolina.

For Europeans, creating protected parks in Africa allowed them to expand their dominion over the continent and quench their thirst for “undisturbed” nature, all without threatening their ongoing expansion of industrialization and capitalism in their own countries. With each new national park came more evictions of Indigenous people, paving the way for trophy hunting, resource extraction, and anything else they wanted to do.

In the mid-19th century, European colonization of Africa was limited, largely confined to coastal regions. But by 1925, when King Albert created his park, Europeans controlled roughly 90 percent of the continent.

At the time, these parks were playgrounds for wealthy Europeans and part of a massive imperial campaign to control African land and resources. Today, there are thousands of protected national parks around the world covering millions of acres, ranging from small enclosures like Gateway Arch National Park in St. Louis to sprawling landmarks like Death Valley in California and Kruger National Park in South Africa. And the world wants more.

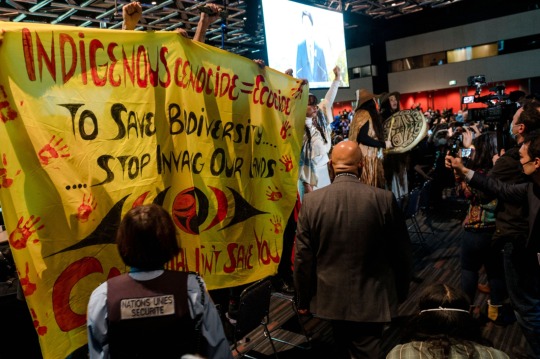

Scientists, politicians, and conservationists are championing the protected-areas model, developed in the U.S. and perfected in Africa. In late 2022, at the United Nations Biodiversity Conference in Montreal, nearly 200 countries signed an international pledge to protect 30 percent of the world’s land and waters by 2030, an effort known as 30×30 that would amount to the greatest expansion of protected areas in history.

So how did protected parks move from an imperial tool to an international solution for accelerating climate and biodiversity crises?

In the early part of the 20th century, the expansion of colonial conservation areas was humming along. From South Africa to Kenya and India, colonial governments were creating protected national parks. These parks provided a host of benefits to their creators. There were economic benefits, including extraction of resources on park land and tourism income from increasingly popular safaris and hunting expeditions. But most of all, the rapidly developing network of parks was a form of control.

“If you can sweep a lot of peasants and Indigenous peoples away from the lands, then it’s easier to colonize the land,” Büscher said.

This approach was enshrined by the 1933 International Conference for the Protection of the Fauna and Flora of Africa, which created one of the first international treaties, known as the London Convention, to protect wildlife. The convention was led by prominent trophy hunters, but it recommended that colonies restrict traditional African hunting practices.

“Conservation is an ideology. And this ideology is based on the idea that other human beings’ ways of life are wrong and are harming nature, that nature needs no human beings in order to be saved,” said Fiore Longo, a researcher and campaigner at Survival international, a nonprofit that advocates for Indigenous rights globally.

The London Convention also suggested national parks as a primary solution to preserve nature in Africa — and as many African countries saw the creation of their first national parks in the first half of the 20th century, the removal of Indigenous peoples continued. The convention was also an early sign that conservation was becoming a global task, rather than a collection of individual projects and parks.

This sense of collective responsibility only grew in the aftermath of World War II, when many international organizations and mechanisms, like the United Nations, were created, ushering in a new period of global cooperation. In 1948, the International Union for Conservation of Nature, or IUCN, the world’s first international organization devoted to nature conservation, was established. This would help pave the way for a new phase of international conservation trends.

By the middle of the 20th century, many countries in Africa were beginning to decolonize, becoming independent from the European powers that had controlled them for decades. Even as they lost their colonies, the imperial powers were not willing to let go of their protected parks. But at the same time, the IUCN was proving ineffective and underfunded. So in 1961, the World Wildlife Fund, or WWF, an international nonprofit, was founded by European conservationists to help fund global efforts to protect wildlife.

Sène-Harper said that although the newly independent African countries nominally controlled their national parks, many of them were run or supported by Western nonprofits like WWF.

“They’re trying to find more crafty ways to be able to extract without seeming so colonial about it, but it’s still an imperialist form of invasion,” she said.

Although these nonprofits have done important work in raising awareness of the extinction crisis, and have had some successes, experts say that the model of colonial conservation has not changed and has only made the problem worse.

Over the years, WWF and other nonprofits have helped fund violent campaigns against Indigenous peoples, from Nepal to the Democratic Republic of the Congo. And amid it all, climate change continues to worsen and species continue to suffer.

In 2019, in response to allegations about murders and other human rights abuses, WWF conducted an independent review that found “no evidence that WWF staff directed, participated in, or encouraged any abuses.” The organization also said in a statement that “We feel deep and unreserved sorrow for those who have suffered. We are determined to do more to make communities’ voices heard, to have their rights respected, and to consistently advocate for governments to uphold their human rights obligations.”

“I think most of [the big NGOs] have become part of the problem rather than the solution, unfortunately,” Büscher said. “The extinction crisis is very real and urgent. But, nonetheless, the history of these organizations and their policies are incredibly contradictory.”

To Indigenous people who had already suffered from decades of colonial conservation policies, little changed with decolonization.

“When we got independence, we kept on the same policies and regulations,” said Mathew Bukhi Mabele, a conservation social scientist at the University of Dodoma in central Tanzania.

In 1992, representatives from around the world gathered in Rio De Janeiro for the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development. The Earth Summit, as it has come to be known, led to the creation of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change as well as the Convention on Biological Diversity, two international treaties that committed to tackling climate change, biodiversity, and sustainable development.

Biodiversity is the umbrella term for all forms of life on Earth including plants, animals, bacteria, and fungi.

Although the Earth Summit was a pivotal moment in the global fight to protect the environment, some have criticized the decision to split climate change and biodiversity into separate conferences.

“It doesn’t make sense, actually, to separate out the two because when you get to the ground, these are going to be the same activities, the same approaches, the same programs, the same life plans for Indigenous people,” said Jennifer Tauli Corpuz, who is Kankana-ey Igorot from the Northern Philippines and one of the lead negotiators of the International Indigenous Forum on Biodiversity.

From left: The 1992 UN Conference on Environment and Development, also known as the Earth Summit, brought together political leaders, diplomats, scientists, representatives of the media, and non-governmental organizations from 179 countries. Indigenous environmentalist Raoni Metuktire, a chief of the Kayapo people in Brazil, talks with an Earth Summit attendee.

In the years following the Earth Summit, biodiversity efforts began to lag behind climate action, Corpuz said.

Protecting animals was trendy during the early days of WWF, when images of pandas and elephants were key fundraising tactics. But as the impacts of climate change intensified, including more devastating storms, higher sea levels, and rising temperatures, biodiversity was struggling to gain as much attention.

“There were 100 times more resources being poured into climate change. It was more sexy, more charismatic, as an issue,” Corpuz said. “And now biodiversity wants a piece of the pie.”

But to get that, proponents of biodiversity needed to develop initiatives similar to the big goals coming out of climate conferences. For many conservation groups and scientists, the obvious solution was to fall back on what they had always done: create protected areas.

This time, however, they needed a global plan, so scientists were trying to calculate how much of the world they needed to protect. In 2010, nations set a goal of conserving 17 percent of the world’s land by 2020. Some scientists have supported protecting half the earth. Meanwhile, Indigenous groups have proposed protecting 80 percent of the Amazon by 2025.

How the world arrived at the 30×30 conservation model

Explore key moments in conservation’s global legacy, from the United States’ first national park in the 19th century to the expansion of colonial conservation areas in the early 20th century and the current push to protect 30 percent of the world’s land and oceans by 2030.

1872: Yellowstone becomes the first national park in the U.S.

1919: King Albert I of Belgium tours Yellowstone, Yosemite, and the Grand Canyon

1925: Albert National Park is established in the Belgian Congo

1933: One of the first international treaties to protect wildlife, known as the London Convention, is created by European conservationists

1948: The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) is established

1961: The World Wildlife Fund, a non-governmental organization, is founded by European conservationist

1992: The Earth Summit in Brazil creates the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD)

2010: CBD sets a goal of conserving 17% of the world’s land by 2020

2022: At the UN Biodiversity Conference, nearly 200 countries set 30×30 as an international goal

In 2019, Eric Dinerstein, formerly the chief scientist at WWF, and others wrote the Global Deal for Nature, a paper that proposed formally protecting 30 percent of the world by 2030 and 50 percent by 2050, calling it a “companion pact to the Paris Agreement.” Their 30×30 plan has since gained widespread international support.

But other experts, including some Indigenous leaders, say the idea ignores generations of effective Indigenous land management. At the time, there was limited scientific attention paid to Indigenous stewardship. Because of that, Indigenous leaders say they were largely ignored in the early years of international biodiversity negotiations.

“At the moment, we did not have a lot of evidence,” said Viviana Figueroa, who is Omaguaca-Kolla from Argentina and a member of the International Indigenous Forum on Biodiversity.

Some experts see the push for global protected areas as a direct response to community-based conservation, which grew in popularity in the 1980s, and saw local communities and Indigenous peoples take control of conservation projects in their area, rather than the centralized approach that had dominated during colonial times.

Some of the chief proponents of 30×30 bristle at the suggestion that they do not support Indigenous rights and say that Indigenous land management is at the heart of the initiative.

In response to a request for comment, a spokesperson from WWF pointed to its website, which outlines the organization’s approach to area-based conservation and its position on 30×30: “WWF supports the inclusion of a ‘30×30’ target in CBD’s post-2020 global biodiversity framework (GBF) only if certain conditions are met. For example, such a target must ensure social equity, good governance, and an inclusive approach that secures the rights of Indigenous peoples and local communities to their land, freshwater, and seas.”

“People have cherry-picked a few examples of where the rights of locals have been tread upon. But by and large, in the vast majority of situations, what’s going on is support of local communities, really, rather than anything to do with violation,” said Dinerstein, who now works at Resolve, a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit focused on environmental, social, and health issues.

But Indigenous advocates say if that were true, they would not keep pushing a model that has already led to countless human rights violations.

“Despite having this knowledge and knowing that people who are not contributing to the destruction of the environment are going to pay for these protected areas, they decided to keep on pushing the target,” Survival International’s Longo said.

The new 30×30 framework agreed to by nearly 200 countries at the UN Biodiversity Conference in December came after years of delay and fierce negotiation. The challenge is now implementing the agreement around the world, a massive task that will require buy-in from individual countries and their governments.

“What was adopted in Montreal is hugely ambitious. And it can only be achieved by a lot of hard work on the ground. And it’s a great document, but it is only a document,” said David Cooper, acting executive secretary of the UN’s Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity.

Part of that work is figuring out what land to protect. And although Indigenous negotiators and advocates did manage to get language that enshrines Indigenous rights into the final agreement, they are still concerned. Over a century of colonial conservation has shown that it only serves the powerful at the expense of Indigenous peoples.

“European countries are not going to evict white people from their lands,” said Longo. “That is for sure. This is where you see all the racism around this. Because they know how these targets will be applied in Africa and Asia. That’s what’s going on, they are evicting the people.”

Dinerstein, however, would argue that European countries have less natural resources to preserve, but more financial resources to help other countries.

“There’s a lot that can be done in Europe,” he said. “So we shouldn’t overlook that as well. I’m just making the point that there’s the opportunity to be able to do much more in other countries that have much less resources.”

Cooper said that in addition to implementation, monitoring and ensuring that rights are upheld will be a crucial task over the next seven years. “There will need to be a lot of work on monitoring. There’s always a justified nervousness that any global process cannot really see what’s happening at the local level and can end up with supporting measures that are perhaps not beneficial at the local level,” he said.

Although Indigenous leaders are going to keep fighting to ensure that the expansion of protected areas does not lead to continued violation of their rights, they are worried that the model itself is flawed. “It’s inevitable that the burden is going to fall again on developing countries,” Corpuz said.

#colonial violence#languages#How the world’s favorite conservation model was built on colonial violence#colonialism#brazil#indigenous populations#Yanomami#bolsanaro#the amazon#amazon rainforest#natural resources#ecology

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spiny Ape

Image © Traci Shepard, accessed at Arcane Beasts and Creatures here

[Cryptozoologists have a field day with Africa, sometimes demythologizing magical creatures, sometimes unearthing old reports of the colonial era, sometimes drawing from new rumors and sightings. And sometimes they just make stuff up. Supposedly, a troop of chimpanzees with spines on their back was filmed attacking a monkey in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, but the video was taken during a covert op by Navy SEALS, so is currently classified. If you believe that, there’s a bridge I have to sell you. Like the bagodaemon or Ozark howler, this appears to be a monster created as a hoax by a single individual. Still, the idea of a quilled ape is a fun one, and I wanted to have a critter that actually works like a folkloric porcupine.]

Spiny Ape

CR 3 N Magical Beast

This creature looks like a chimpanzee, with long arms, short legs and a heavy brow. The main difference is the coat of quills that covers its back.

Spiny apes are relatives of chimpanzees, with sharp quills growing from their backs that they can fire like arrows. The improbability of this attack form has led some sages to suggest that spiny apes were created by some mad mage or disgruntled druid. Another hypothesis is that the creatures were created by the fey in the First World as an experiment that was discarded because chimpanzees are dangerous enough without missile weapons.

A spiny ape troop typically hunts by ambush, attacking from the trees and firing down on passing prey. If a foe is capable of fighting back, say with ranged weapons of their own or magic, a few members of the troop will descend to the ground and engage them in melee to distract them. Spiny apes are reasonably skilled at teamwork before the first kill is made, but then begin to compete to get their share of meat.

Spiny ape society is organized like that of common chimpanzees—males are violently aggressive towards strangers and towards females, and females typically mate with multiple males in order to confound paternity and reduce the chances of infanticide. They are omnivorous, but eat mostly meat, supplemented with fruit. They happily attack and eat other apes, and populations of gorillas and chimpanzees are low where spiny apes live.

Spiny Ape CR 3

XP 800

N Medium magical beast

Init +4; Senses darkvision 60 ft., low-light vision, Perception +6

Defense

AC 16, touch 14, flat-footed 12 (+4 Dex, +2 natural)

hp 30 (4d10+8)

Fort +6, Ref +8, Will +3

Defensive Abilities quill defense

Offense

Speed 30 ft., climb 30 ft.

Melee bite +6 (1d4+2), 2 slams +6 (1d4+2)

Ranged 2 quills +8 (1d4+2 plus pain)

Statistics

Str 15, Dex 19, Con 14, Int 2, Wis 14, Cha 7

Base Atk +4; CMB +6; CMD 20

Feats Point Blank Shot, Precise Shot

Skills Acrobatics +8, Climb +14, Perception +6, Stealth +8

Ecology

Environment warm forests

Organization solitary, pair or troop (3-12)

Treasure none

Special Abilities

Pain (Ex) Whenever a creature takes damage from a spiny ape’s quill attack or its quill defense, that creature must make a successful DC 14 Reflex save or one quill breaks off in its flesh, causing the target to become sickened until all embedded quills are removed. Removing one quill requires a DC 15 Heal check made as a full-round action. For every 5 by which the check is exceeded, one additional quill can be removed. On a failed check, a quill is still removed, but the process deals 1d4+1 points of damage to the victim. The save DC is Strength-based.

Quills (Ex) A spiny ape can fire two quills from its back as a standard action. Treat this as a ranged attack with a thrown weapon, with a range increment of 20 feet. A spiny ape has ten quills ready for use each day.

Quill Defense (Ex) A creature that strikes a spiny ape in melee must succeed a DC 16 Reflex save or take 1d4+1 damage from its quills and be exposed to the spiny ape’s pain attack. Weapons with the reach property do not endanger their wielders in this way. A spiny ape that has used all ten of its quill attacks for the day still can use this ability, but the creature gains a +4 circumstance bonus on its saving throw. The save DC is Dexterity based.

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

Round 2, match 15: African apes

Western lowland gorilla (Gorilla gorilla gorilla)

These huge, powerful apes are found in the lowland tropical forests of Western Africa. They are highly sexually dimorphic, and dominant males are often called silverbacks for their light grey backs. They eat leaves, fruits, roots, tree bark, and occasionally small animals. They are also known to use tools, and famously Koko the gorilla was apparently able to communicate using sign language, although the extent to which she understood has been questioned by many scientists. I chose to use this subspecies because their full scientific name (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) is funny to me.

Bonobo (Pan paniscus)

Once known as the pygmy chimpanzee, the bonobo is now recognised as a separate species. They live in tropical forests south of the Congo River, and eat fruit, leaves, honey, and small animals like insects and mammals. They are very social and less violent than chimpanzees. They’re also really horny, like all the time. They’re the only non-human species known to engage in tongue kissing and face-to-face sex, because of course they are. And as expected from a species whose sex lives have been studied as much as they have, both male-male and female-female relations have been documented.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

There are countless cases in which the psychoactive properties of certain plants have been discovered by human beings through observation of animal behavior. In the forests of Gabon and the Congo, natives relate that they long ago noticed wild boars digging up and eating the hallucinogenic roots of the iboga bush (Tabernanthe iboga, of the family of Apocynaceae). In consequence, the boars become frenzied, leaping in every direction, displaying inexplicable fear reactions and suffering hallucinations. Porcupines and gorillas also intentionally feed on iboga for its effects. It was by observing and imitating these animals that natives deduced, and then experienced, the visionary properties of the plant.

In the course of my own researches in Gabon, which explored the use of iboga in the Buiti religious cult practiced by the Fang, Mitsogho, Apindji, and other Bantu tribes inhabiting the equatorial forest, I was informed by many different people that various animal species also eat iboga to drug themselves. A Mitsogho shaman, or nganga, told me of iboga use among male mandrills. Mandrills live in widespread communities and adhere to a rigid hierarchical structure. At the top of the ladder is the alpha male, to whom other powerful males submit; these, in turn, dominate yet weaker males.

When a male mandrill must engage in combat with another, either to establish his claim to a female or to climb a rung of the hierarchical ladder, he does not begin to fight without forethought. Instead, he first finds and digs up an iboga bush, eating its root; next, he waits for its effect to hit him full force (which can take from one to two hours); and only then does he approach and attack the other male he wants to engage in battle. The fact that the mandrill waits like this to feel the full effect of the drug before attacking demonstrates a high level of premeditation and awareness of what he is doing.

-- Samorini Giorgio, Animals and Psychedelics: The Natural World and the Instinct to Alter Consciousness

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gorilla Trekking: A Wildlife Adventure Like No Other

Gorilla trekking is an exciting and awe-inspiring wildlife adventure that allows you to get up close and personal with some of the world's most magnificent creatures. The experience typically involves hiking through lush rainforests, tracking endangered mountain gorillas in their natural habitat, and spending time observing and interacting with them in their family groups.

Gorilla trekking is an unforgettable experience that provides a unique opportunity to witness these gentle giants in the wild, where they live, eat, and play. As you venture into the gorilla's habitat, you'll be surrounded by breathtaking scenery, dense vegetation, and diverse wildlife. The trek itself can be a challenging and exhilarating experience, as you navigate steep terrain and unpredictable weather conditions.

Gorilla trekking is available in several locations across Africa, with the most popular destinations being Uganda, Rwanda, and the Democratic Republic of Congo. These countries are home to several national parks, such as Bwindi Impenetrable Forest, Virunga National Park, and Volcanoes National Park, where visitors can engage in guided tours to observe these majestic creatures.

In addition to providing a thrilling adventure, gorilla trekking also plays a crucial role in conservation efforts. By supporting ecotourism, visitors contribute to the preservation of gorilla habitats and the protection of these magnificent creatures. Gorilla trekking is a unique and meaningful way to connect with nature, learn about conservation efforts, and create lasting memories.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ecuador Moves to Expand Drilling in the Amazon

https://sciencespies.com/environment/ecuador-moves-to-expand-drilling-in-the-amazon/

Ecuador Moves to Expand Drilling in the Amazon

YASUNÍ NATIONAL PARK, Ecuador — In a swath of lush Amazon rainforest here, near some of the last Indigenous people on Earth living in isolation, workers recently finished building a new oil platform carved out of the wilderness.

Teams are drilling in one of the most environmentally important ecosystems on the planet, one that stores vast amounts of planet-warming carbon. They’re moving gradually closer to an off-limits zone meant to shield the Indigenous groups. It turns out that some of the country’s largest oil reserves are found here, too.

Ecuador is cash-strapped and struggling with debt. The government sees drilling as its best way out. The story of this place, Yasuní National Park, offers a case study on how global financial forces continue to trap developing countries into depleting some of the most biodiverse places on the planet.

Countries like Ecuador are “against the wall,” said María Fernanda Espinosa, an Ecuadorean diplomat and a former president of the United Nations General Assembly.

Drilling in this part of the rainforest wasn’t Ecuador’s first choice. In 2007, Rafael Correa, the president at the time, proposed a novel alternative that would have kept the oil reserves in a parcel here designated as Block 43, estimated then at around a billion barrels, in the ground.

Under that plan, countries would have created a fund of $3.6 billion, half of the oil’s estimated value, to compensate Ecuador for leaving its reserves untouched. Supporters of the idea said it would have been a win for the climate, for biodiversity and for Indigenous rights. And, they said, it would have been a precedent-setting moral victory: A small, developing nation would have been paid for giving up a resource that helped make places like the United States and Europe so wealthy.

But, after early fanfare, only a pittance in contributions trickled in. Ecuador turned to China for loans, around $8 billion over the course of the Correa administration, some to be repaid in oil.

The failure of that plan led to the expansion of drilling in Block 43.

Most of Ecuador’s oil lies beneath the Amazon rainforest. More than a third of the government’s revenue comes from oil.

Ecuadorean leaders say they simply can’t walk away from oil money in a country where as many as one in four children suffers from malnutrition.

“Now that the global trend is to abandon fossil fuels, the time has come to extract every last drop of benefit from our oil, so that it can serve the poorest while respecting the environment,” the current president, Guillermo Lasso, said last year.

Other nations are also looking to new oil development, even though the International Energy Agency has said countries must stop new projects to avoid catastrophic climate change. Developing nations say they should be allowed to keep using fossil fuels, since, historically, they’re least to blame for climate change. But these countries are often home to the very ecosystems that are most valuable in helping to stave off global warming and biodiversity collapse. The Democratic Republic of Congo, for example, has put up for auction oil blocks that include rainforest, peatlands and parts of a sanctuary for rare mountain gorillas.

In Ecuador, the oil industry insists that drilling can occur with little damage, but scientists say that even the best cases so far have led to deforestation and other pressures.

More oil extraction couldn’t come at a worse time for the world’s forests. With the Amazon weakened by deforestation and climate change, scientists warn that the forest is approaching a threshold beyond which it could degrade into grassland. Some areas are already emitting more carbon than they store, a ticking time bomb of greenhouse gases.

Inside the Amazon Rainforest

Drilling for Oil: A novel idea to leave Ecuador’s vast oil reserves in the ground fizzled for lack of international support. Now, struggling under painful debt, the government wants to expand drilling in the Amazon.

At a ‘Tipping Point’?: Losing the Amazon would be catastrophic for tens of thousands of species. And some scientists fear that it may become a grassy savanna — with profound effects on the climate worldwide.

Illegal Airfields: The Times identified more than 1,200 unregistered airstrips across the Brazilian Amazon. Many of them are part of criminal networks that are destroying Indigenous land and threatening its people.

Retracing a Murder: A journalist and an activist set off deep into the Amazon to meet Indigenous groups patrolling the forest, and then they vanished. Our reporter followed their final steps.

“Ecuador’s greatest wealth is its biodiversity,” said Carlos Larrea, a professor at Simón Bolivar Andean University in Quito, the capital, who helped to design the failed fund. The destruction of Yasuní, he said, “is suicide.”

‘Nature Always Loses’

Egrets over the Yasuní region.

Yasuní brims with life. It trills, squawks and hoots. The world’s tiniest monkeys, called pygmy marmosets, scamper over branches, and the world’s largest rodents, capybaras, loll along riverbanks.

In one parcel of just 25 hectares, or about 60 acres, scientists have documented roughly 1,000 species of native trees, around the same number that exist in the entire United States.

No region of land on Earth is more rich in biodiversity than this one, where the Amazon climbs into the foothills of the Andes, according to scientists. The genetic diversity is a vast, untapped resource that could unlock cures for diseases and open doors to technological innovations. But the fragmentation here has already started.

“Nature always loses,” said Renato Valencia, a forest ecologist at Pontifical Catholic University of Ecuador who has studied this area for decades. “When it comes to economic matters, that’s the rule.”

Even under the industry’s best practices, the ecosystem has suffered.

In the 1990s, as oil production began near those 25 hectares, executives went out of their way to protect nature, scientists said. They strove to keep deforestation to a minimum and hired scientists to study the local biodiversity.

Yasuní is one of the most biodiverse places on the planet.

“We kept hoping that this would be an example whereby oil development could coexist with a wild forest and its biota,” said Robert S. Ridgely, an ornithologist who led the study on birds. “But it just didn’t turn out that way.”

The worst environmental damage came not from oil contamination, the scientists said, but from the company’s road. Despite strict controls, it attracted new Indigenous Ecuadoreans to the area, who cut down trees to grow crops. Local hunters started killing more animals to sell, including threatened species. Illegal logging is a problem.

The New York Times reached out to authors of the company-funded studies. Six of seven responded, each expressing grave concern about the new drilling in Block 43.

“It is going to be another complete disaster,” said Morley Read, a zoologist who conducted the study on reptiles and amphibians.

People are at risk, too. In Yasuní, an unknown number of men, women and children live in what’s known as voluntary isolation, rejecting contact with the outside world. They are called the Tagaeri and the Taromenane.

Their reserve and a related buffer zone are off-limits to drilling, but government officials have discussed shrinking the protective zone to reach more oil.

“That’s where nature put it,” said Fernando Santos, the Ecuadorean energy minister, in an interview in November. “And that’s where we need to get it from, albeit very carefully.”

A Nation ‘Dependent on Oil’

Ramiro Páez Rivera, right, discussed drilling methods meant to reduce deforestation.

Oil has been flowing out of Ecuador’s Amazon for half a century, ever since American companies discovered it there. In 1972, a symbolic first barrel was paraded through the streets of Quito by the military. “The people cannot contain their excitement,” said the narrator of a newsreel filmed that day.

Per capita gross domestic product almost doubled in the following fifty years, a slightly faster pace than Latin America as a whole. Many credit oil.

“There has been a change from a very backward Ecuador to an Ecuador that has progressed not to the first world but to the middle — a breakthrough,” Mr. Santos, the energy minister, said.

But as oil revenues grew, global markets allowed the government to borrow more heavily.

“The thing that you see in Ecuador is that whenever Ecuador has experienced the oil booms, that’s when the debt of Ecuador has skyrocketed,” said Julián P. Díaz, a professor of economics at Loyola University Chicago.

Economists say poorer countries get easily caught in this kind of debt trap because they have less robust economies to begin with and typically borrow at elevated interest rates, since they’re considered riskier.

“Obviously we are in monstrous debt,” Mr. Santos said. But, while he recognizes that oil played a role in creating the problem, he also sees oil as the solution. With more drilling and mining development, he said, “the country will be able to get out of debt.”

However, economic gains have barely trickled down to communities that have lived close to oil development for decades. More than half the people who live in the Ecuadorean Amazon, where the vast majority of the country’s oil comes from, are poor.

Erin Schaff/The New York Times

One Indigenous community, Yarentaro, is only a short walk from a cluster of oil wastewater wells.

Despite three decades of oil production nearby, the community lacks a sanitation system and all water is collected from a nearby river.

The 90-member community has a school where all ages are grouped in a single classroom.

No one has ever gone to college, which is what the community’s president, Daniel Huepihue Cahuiya Iteca, dreams for his daughters. “There is nothing in Yarentaro,” he said.

Ramiro Páez Rivera, an executive who has worked for several oil companies in the area, said it was the government’s job to put oil taxes to good use.

“We pay millions of dollars,” he said. “People don’t even have potable water.”

Last year, thousands of Indigenous Ecuadoreans staged an 18-day strike that stopped much of the country’s oil production. “We don’t want oil,” said Leonidas Iza, president of the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador, which helped lead the protests.

But even as protesters demanded an end to the president’s plans to double oil production, they also insisted the government bring down fuel prices, something that typically creates more demand.

“There is a harsh reality that in these 50 years our economies have become dependent on oil,” Mr. Iza said.

‘The World Has Failed Us’

Along Vía Auca, a decades-old oil road that has led to deforestation near Yasuní National Park.

The proposal in 2007 to leave the oil in the ground was an effort to chart a different path. A surprising figure pushed the proposal: the minister of energy, Alberto Acosta.

It was “the minister of petroleum proposing not to extract the petroleum,” Mr. Acosta recalled. As a younger man, he’d accepted as gospel that oil was the key to lifting Ecuador out of poverty. But after decades of production, the biggest effects he saw were pollution and deforestation.

So Ecuador asked the world for $3.6 billion, half of what it predicted it would make by selling the fuel. At first, there were positive signs. The United Nations agreed to manage the fund. Germany and Italy pledged resources.

But some governments didn’t trust the president, Mr. Correa, a populist who had intentionally defaulted on foreign debt. Many seemed perplexed by the idea of paying a country not to do something. Mr. Correa was accused of blackmail because he planned to drill if the money didn’t materialize.

As the Yasuní proposal lost momentum, China took on a growing influence in Ecuador, stepping in with billions of dollars in loans, some to be repaid in oil.

In the end, the Yasuni proposal only raised about $13 million. “The world has failed us,” Mr. Correa told the nation in August 2013.

Mr. Correa now lives in Belgium and faces arrest in Ecuador because of a corruption conviction.

Seeking ‘Another Type of Economy’

The river near Yarentaro is the community’s only source of water.

After the failure of the Yasuní project, a state-owned oil company, now part of Petroecuador, started knocking on doors in Indigenous communities throughout Block 43, offering money, housing and sanitation projects.

Today, twelve platforms dot the forest, connected by a gravel road.

From each platform, workers are drilling dozens of wells, bent in different directions to avoid further deforestation. Hundreds of workers toil in shifts, 24 hours a day.

“We are making an aggressive push given the limits of what can be done there,” said Hugo Aguiar, Petroecuador’s general manager.

Some people in the surrounding communities, like Holmer Machoa, worried about oil pollution and wanted to explore ecotourism instead.

But much like the rest of Ecuador, many living in Yasuní see no comparable alternatives to oil.

Many local residents fish and grow corn, cassava and cocoa, but mostly for their own use. “There’s no source of income,” said Alexandra Avilés, the president of Llanchama, one of the communities.

However, it’s unclear how long the oil in Block 43 will be worth the investment. The heavy oil is less valuable and emits more carbon than lighter types. Over 90 percent of what’s pumped is toxic water that needs to be removed and treated, making operations more expensive.

Many economic alternatives have been studied, such as carbon offset projects and developing markets for local products like nuts.

But oil is one of the most profitable industries in the world. To compete, government policy and global collaboration are needed, researchers say.

One idea gaining traction involves “debt for nature” deals. Ecuador is considering a big one in coming months, getting banks to renegotiate a sizable portion of its debt in exchange for investing in a new marine reserve off the Galápagos Islands.

Another country may try its own version of the Yasuní proposal. Seychelles, an Indian Ocean island nation under threat from rising sea levels, is sponsoring oil exploration that could be used as leverage when asking wealthy countries to help fund renewable energy projects.

Pressure against oil in Ecuador continues to build. After years of legal hurdles, a ballot measure asking if the government should keep Block 43 crude oil underground may finally go to a vote.

“We will run all the oil blocks down, run all the ecosystems down, but we won’t solve the problem of Ecuador’s economy,” Mr. Iza, the Indigenous leader, said. “We must think of another type of economy.”

#Environment

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

GUIDE TO GORILLA TREKKING TO UGANDA

This Mountain Gorilla trekking guide to Uganda provides information about Mountain Gorillas which are an endangered primate species that can only be found in the Forested areas of the Virunga Massif stretching from Uganda, Rwanda to DR Congo. In Uganda, there are two protected national parks where you can see the endangered mountain gorillas; Bwindi Impenetrable Forest National Park and the Mgahinga Gorilla National Park both located in southwestern Uganda.

The current mountain gorilla population stands at about 1004 individuals, half of which are found in Uganda. Gorillas are gentle Giants and are closely related to humans since they share up to 96% of their DNA composition with Humans. Unlike the lowland Gorillas, the mountain gorillas have never been able to survive in captivity and therefore no mountain gorillas are found in Zoos outside of Africa.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

DR Congo 🇨🇩

Facts about DR Congo, the richest Country with Natural Resources in the world 🇨🇩

1. Music is its biggest export

2. Kinshasa is world's second largest French speaking city.

3. Locals eat mayo with everything

4. Kinshasha and Brazaville are the world's closest capitals.

5. The Wildlife is Phenomenal

6. The Congo isn't overrun by the Ebola Virus

7. Congo played a role in World War II

8. DRC is one of the Countries in East and Central Africa where one can find the Mountain Gorillas and the Eastern Lowland Gorillas.

9. The Democratic Republic of the Congo is the second largest country in Africa. It borders nine countries: Angola, Burundi, the Central African Republic, the Republic of Congo, Rwanda, South Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zambia.

10. The people of the DRC represent over 200 ethnic groups, with nearly 250 languages and dialects spoken throughout the Country.

11. DRC has more than 450 tribes , one of biggest hydro dam in the world, the biggest stock of water, second large river in the world, second biggest forest after amazonia, has the oldest and biggest park in Africa( virunga), is the only one country in the world with okapi animal, biggest world s minerals's stuff: copper, lithium, cobalt, gold, coltan, cassiterite, nobium, gold, diamond, uranium.., one of the peaceful and kind population in the world, hiroshima & Nagasaki nuclear bomb were made by uranium from the south EST of DRC, has the second biggest island in africa( Idjwi, island) second deepest lake in the world after baikal lake in Russia, 12 national parks with all types of wild animals,. and so on

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Democratic Republic of the Congo has announced it will auction oil and gas permits in critically endangered gorilla habitat and the world’s largest tropical peatlands next week. The sale raises concerns about the credibility of a forest protection deal signed with the country by Boris Johnson at Cop26.

On Monday, hydrocarbons minister Didier Budimbu said the DRC was expanding an auction of oil exploration blocks to include two sites that overlap with Virunga national park, a Unesco world heritage site home to Earth’s last remaining mountain gorillas.

The planned sale already included permits in the Cuvette Centrale tropical peatlands in the north-west of the country, which store the equivalent to three years’ global emissions from fossil fuels.

The Congo basin is the only major rainforest that sucks in more carbon than it emits and experts have described it as the worst place in the world to explore for fossil fuels.

Environmental groups have urged the leading fossil fuel companies to sit out the auction and said president Felix Tshisekedi, who signed a $500m (£417.6m) deal to protect the forest with Boris Johnson on the first day of Cop26 last year, should cancel the sale. The Congo basin rainforest spans six countries and regulates rainfall as far away as Egypt.

Speaking to the Guardian, Budimbu acknowledged environmental concerns but defended his country’s right to exploits its natural resources. He said revenue from the oil and gas projects was needed to protect the Congo basin forest and to economically develop the country.

“We have a primary responsibility towards Congolese taxpayers who, for the most part, live in conditions of extreme precariousness and poverty, and aspire to a socio-economic wellbeing that oil exploitation is likely to provide for them,” he said.

Earlier this week, Budimbu told the Financial Times that Hollywood actors Ben Affleck and Leonardo DiCaprio had got “on their high horse” and helped halt oil and gas exploration in Virunga after a 2014 Netflix documentary, but said this time the DRC would not be stopped.

#congo#drc#mountain gorillas#climate change#fossil fuels#cop26#tropical peatlands#unesco#virunga#carbon sink

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Dzanga Bai Elephant Enclave There are many ways that living creatures shape, color, and transform the Earth. Phytoplankton can paint the ocean with color when they multiply in prodigious blooms. Insect infestations can deplete or destroy forest cover. Beavers build dams that flood wetlands and sometimes create small lakes. And humans leave their fingerprints all over the planet. Amid the rainforests in the Central African Republic, there is a place where forest elephants have carved out a niche that is clearly visible from space. Known as Dzanga Bai, this swampy clearing attracts tens to hundreds of these massive herbivores every day. Unique to the Congo Basin, bais are sandy and muddy open patches of forest that are pockmarked with puddles, streams, and watering holes full of mineral-rich water. Dzanga Bai is believed to have been cleared and maintained by African forest elephants that trample or eat much of the vegetation in this spot. The waters there are rich in minerals and salts that the elephants need but cannot obtain from rainforest vegetation. The minerals originate from an intrusion of volcanic rock (dolerite) not far below the land surface. According to research led by biologist Andrea Turkalo of the Wildlife Conservation Society, anywhere from 50 to 150 forest elephants arrive at the bai each day, with several thousand living in the surrounding area. Using their feet, they dig holes in the surface down to the mineral-rich water in the substrate; sometimes they use their trunks to work their way through surface water to obtain minerals. The Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8 acquired these natural-color images of Dzanga Bai, the village of Bayanga, and the wider protected areas on March 28, 2021. For scale, Dzanga Bai is estimated to be about 500 meters (1,600 feet) long. The wider region is dominated by rainforest that is interspersed with streams, marshlands, and the bais. It all sits within the Congo Basin, the second largest rainforest in the world. At this intersection between the Central African Republic, Cameroon, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, governments and conservation groups have been working since 1990 to protect forestlands in a 17,000 square kilometer area called the Sangha River Trinational. UNESCO has declared the area—including Lobéké National Park (Cameroon), Nouabalé-Ndoki National Park (Republic of Congo), and Dzanga-Ndoki National Park (the Central African Republic), and the Dzangha Sangha Special Reserve (CAR)—to be a World Heritage Site. Turkalo spent more than 25 years living and working in Dzanga-Ndoki National Park, producing a comprehensive natural history and demographic catalog of more than 1,600 known forest elephants at the bai. She found that male elephants have a lower survival rate, most likely due to hunting by humans looking to harvest ivory and bushmeat. Her long-term observations also revealed that forest elephants reproduce slower than the savannah species. In an earlier study (Turkalo was a contributor), researchers estimated that the number of forest elephants in the Congo Basin declined by 62 percent between 2002 and 2011. The species lost about 30 percent of its geographic range, and the population was estimated to be less than 10 percent of its potential size. The elephants are not only threatened by poachers, but also by deforestation for logging and farming, and perhaps by exposure to disease from human contact. Besides forest elephants, the region includes important habitat for the western lowland gorilla, the bongo (forest antelope), sitatunga (swamp antelope), forest buffalo, chimpanzees, and many species of birds. Indigenous Ba’Aka and Sangha Sangha people have lived in the area for thousands of years, using their knowledge of plants and traditional fishing techniques to sustain a culture in the rainforest. NASA Earth Observatory images by Lauren Dauphin, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey and data from OpenStreetMap. Story by Michael Carlowicz.

2 notes

·

View notes