#Continental Philosophy

Text

On Heights of Despair, Emil Cioran

#emil cioran#continental philosophy#philosophy#classic literature#english literature#romanticism#existentialism#dark academia aesthetic#nihilism#absurdism#dark academia#taylor swift#richard siken#jane austen#kafka#oscar wilde#lord byron#keats#the secret history#achilles#Shakespeare#homer#light academia aesthetic#cottage core#henry winter#art#poetry#painting#book aesthetic#dead poets society

373 notes

·

View notes

Text

So, that excerpt from Theodor Adorno's Minima Moralia was quite interesting and so I decided I should put Adorno on my list, and I googled best Adorno translation which led me to this reddit thread which contains the following comment from user QuesyCampaign:

If you end up with the Ashton translation of [Negative Dialectics] (the only English translation to have been printed), there are some common terms that are completely mistranslated that you can just mentally adjust for (Jameson mentions a few of these in his Late Marxism):

Vermittlung and related words often translated as "transmission", "transmitted", etc. - should be mediation/mediated. As in the disastrous "Transmission is transmitted by what it transmits".

Anschauung translated as "vision" instead of the accepted English rendering "intuition" in philosophical contexts.

Direct/indirect - if you ever see these, replace with "immediate/mediate".

None of this will help with the significant failure to do justice to Adorno's German, nor with those sentences that just don't make sense, but they should help. If you ever work on or need to cite a passage, make sure you consult the German and the other translations first!

Guys, is it possible that a lot of continental philosophy's reputation as obtuse and incomprehensible is just because the people translating it are really bad at their jobs?

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

#occult#esoteric#neo-platonism#philosophy#continental philosophy#semiotics#structuralism#cultural appropriation#religion#hermetic#qabalah#hermetic qabalah#hellenism#pagan#thelema

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nothing truly real is forgotten eternally, because everything real comes from eternity and goes to eternity.

Paul Tillich, The Eternal Now.

#philosophy tumblr#philoblr#german philology#author#philosopher#mystic#paul tillich#metaphysics#continental philosophy#existentialism#eternity#dark academia#life quotes

21 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Guilt is the uncomfortable certainty that we are not what we could have been.

Michael Sugrue

#guilt#wasted potential#michael sugrue#philosophy#continental philosophy#heideggerian#hermeneutic phenomenology#spirituality

81 notes

·

View notes

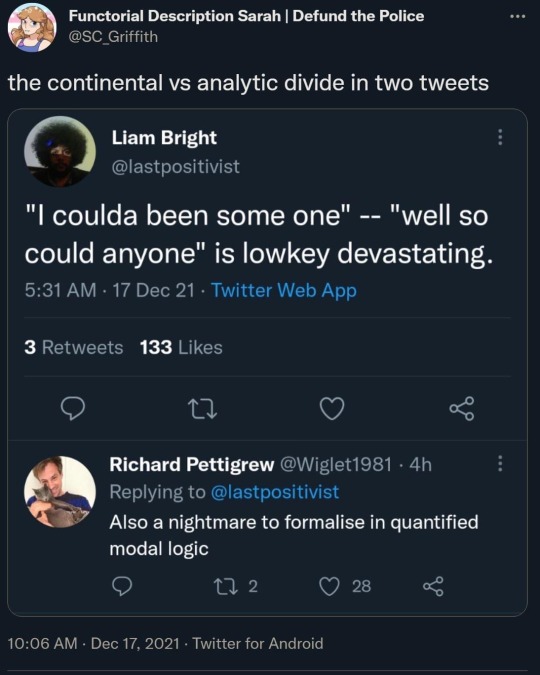

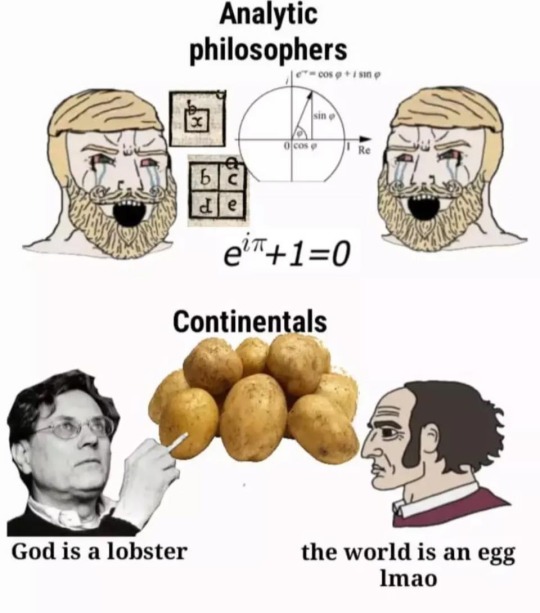

Text

Seen on Facebook. Seems on point. Though, TBF, what do I even know? I’m just a former future philosopher.

#philosophy#continental philosophy#analytic philosophy#this is a shitpost#please don’t freak out#I’m truly sorry#funposting#eliza.txt

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nietzsche and Nihilism

If there's one thing that really grinds my gears it's when people treat Nietzsche as some sort of face of nihilism. I think anyone who is well-versed in Nietzsche's work would agree that the guy is definitely not a nihilist, as he is very openly against it in almost all his works.

I believe this misunderstanding of Nietzsche's philosophy mostly comes from the averages person's understanding of worth.

When Nietzsche said, "God is dead," he was referring to the objective meaninglessness of the world. A lot of people take this at face value, understanding objective meaninglessness as absolute meaninglessness. However, this is not the point Nietzsche was trying to make at all.

In our age of enlightenment values and reason, the western man values objectivity and shuns subjectivity (If you want to read more about the negative effects of enlightenment principles, Max Horkheimer and Theodor W. Adorno's Dialectic of Enlightenment is great). This sort of "facts over feelings" mindset is exactly what led to the nihilist interpretation of Nietzsche being so common. When people read that this guy thinks that objective meaning does not exist, they can't fathom any other meaning existing, because their whole life has been built around putting objectivity on a pedestal, they cannot begin to think about finding anything of significant value through their own subjectivity.

However, this is exactly what Nietzsche is proposing in his work. Objective meaning may be gone, but that does not mean that meaning is impossible, we should instead chose what has meaning to us, based on our own subjectivity. That is what he means when he speaks of the "will to power." My personal understanding of the will to power is simply the desire to be yourself ("simply" is perhaps the wrong word, it's much more nuanced than just "being yourself" but I think it sums it up nicely).

In fact, Nietzsche's main criticism of the modern Christian church was actually that it was "necessarily nihilistic." Modern Christianity puts all its focus on the afterlife. Even if they claim to be worried about being kind and spreading the truth of God, at the end of the day they are only doing that so they can go to heaven when they die. Taking the emphasis off of this life and placing it on the afterlife is precisely what makes modern Christianity nihilistic to its very core.

A notion Nietzsche touches on briefly after his denouncement of modern christianity is that of eternal recurrence. On this, he claims that we should live our lives in such a way that we would be happy to live it over and over again for all eternity. A lot of people dislike this claim, and point out that a lot of people aren't born in circumstances in which they can be happy over and over again (ex: because of poverty, discrimination, political situations). I don't disagree with this at all, there are an incredible amount of people who have to live in situations out of their control which make them unhappy with their life. However, you have to remember that Nietzsche is much more metaphysically inclined. When he says you should live a life you would want to life over and over again, he is more talking about the person you are. You should make choices about your virtues and your morals which would make you happy about the person you are, so much so that you would want to be you over and over again, no matter your external circumstances.

I actually used to hate Nietzsche, as I had only heard of him through this sort of depressed high school boy view that twisted him into a nihilist. However, once I read him for myself, I found his message extremely inspiring, and helped me mentally a lot. The idea of being yourself no matter your circumstances is a beautiful one, and I think it's really sad that most people just view Nietzsche as the nihilism guy.

Remember to be yourself!!!! Nietzsche said so!!!!!!

For anyone who wants to read it, here's a bonus question from an exam that I took this semester where I basically said the same thing as above, but it's worded more concisely I think:

"It is often claimed that Nietzsche is a nihilist and his philosophy is nihilistic in nature. Do you agree with this claim? Indeed what is behind Nietzsche’s denying modern society, traditional values, morality, and Christianity? How would you argue?

I strongly believe that Nietzsche is not a nihilist. In his claim that there are no objective virtues, he is not negating the meaning of human life, he is stating that there are no universal values. I think a lot of the misunderstanding of this claim making Nietzsche a nihilist comes from people's view of subjective vs objective value. Objective values are not inherently more "real" than subjective ones, and I believe this is where the most common mistake is made. Nietzsche advocating for subjective virtues does not make these virtues any less significant than objective ones. Life still has meaning, but it's up to every individual to decides on those virtues for themselves. In Nietzsche's denying of society, traditional values, morality, and Christianity come from his advocation of individuality, and subjective values. He denies society, and Christianity because it values a slave mindset, and thus hatred (ressentiment) of "the other," even denouncing modern Christianity for being "necessarily nihilistic" for focusing on the afterlife rather than our current one. He denies traditional values as well as morality because they are both discussed from a universal, objective standpoint. In all four of these, he does not deny them because they give meaning to life, or because he advocates for people doing whatever they want, he denies them because they take away the existential value of the individual. Thus, I would conclude that Nietzsche is definitely not a nihilist. Life's meaning is not removed when we don't have the guiderails of the objective to tell us how to make choices. If anything, life would have a more personal, passionate meaning when the individual gets to decide for themselves what gives their life meaning."

#nietzche#friedrich nietzsche#existentialism#nihilism#philosophy#western philosophy#continental philosophy#the enlightenment#morality#ethics#critical theory

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Our feminine friends have in common with Bonaparte the belief that they can succeed where everyone else has failed.”

— Albert Camus, The Fall

#what did he mean by this#it sounds like a burn against both Napoleon and women#this is Napoleon’s feminist arc#Napoleon#napoleon bonaparte#Albert Camus#the fall#Camus#lol#quote#La Chute#literature#lit#French literature#napoleonic era#philosophy#absurdism#french philosophy#French philosophers#continental philosophy#France#French#first french empire#women#quotes

39 notes

·

View notes

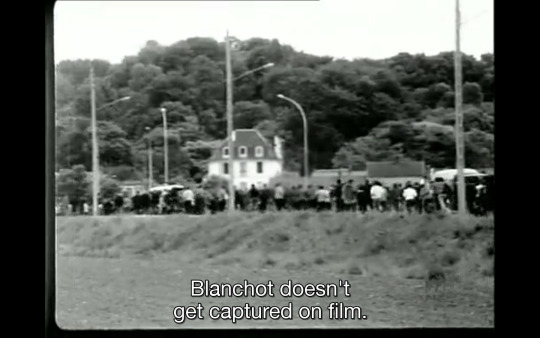

Photo

Hugo Santiago

- Un siècle d'écrivains : Maurice Blanchot

1998

#hugo santiago#maurice blanchot#documentary#french film#continental philosophy#philosophy#1998#effacement#self effacement#disappearance

115 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Nietzsche#Friedrich Nietzsche#Beyond Good and Evil#Beyond Naughty and Nice#Christmas#Santa Claus#Ubermensch#eternal recurrence#ressentiment#philosophy#German philosophy#moustache#Hegel#Foucault#Habermas#Ho Ho Ho#Continental philosophy#Genealogy#Gay Science#Zarathustra#pun#Penguin Classics#penguins#naughty#nice

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

If there was a trolley and its parts were gradually replaced until none of the original parts remained and there was no one there to hear it and it was a copy without an original

#philosophy#deep thinking#deconstruction#postmodernism#post structuralism#meta narrative#thinkering#intellectual#deep thoughts#the west#continental philosophy#dark academia#kant#deleuze#guattari#frankfurt school#descartes#foucauldian#panopticon#psychoanalysis#introspection#the matrix#dialectics#paradigm shift#master morality#appollonian#socratic method#object-oriented ontology#brain in the vat#posthumanism

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

The same feeling of not belonging, of futility, wherever I go: I pretend interest in what matters nothing to me, I bestir myself mechanically or out of charity, without ever being caught up, without ever being somewhere. What attracts me is elsewhere, and I don’t know where that elsewhere is.

The trouble with being born, Emil Cioran

#emil cioran#philosophy#french philosophy#continental philosophy#literature#classic literature#english literature#french literature#dark academia#dark academia aesthetic#book aesthetic#cottage core#romanticism#nihilism#literature quotes#lord byron#shelley#keats#jane austen#kafka#light academia aesthetic#existentialism#art#painting#poetry#tagamemnon#taylor swift#ancient greek#the secret history#dead poets society

219 notes

·

View notes

Text

"When she is alone in the rooms I hear her humming to keep herself from thinking."

-Jean-Paul Sartre, Nausea

#literature#existentialism#philosophy#being alone#existential thoughts#continental philosophy#thoughts#intj#book quotes#jean paul sartre

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

To whatever degree he may have desacralized the world, the man who has made his choice in favor of a profane life never succeeds in completely doing away with religious behavior.

Mircea Eliade, The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion.

#philosophy tumblr#philoblr#continental philosophy#author#philosopher#mircea eliade#existentialism#religion#ontology#metaphysics#meta ethics#dark academia#life quotes

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

BERGSONIAN PROBLEMS OF OMNISCIENCE

I was pondering some problems related to Omniscience and Free Will. A few passages from Bergson’s Time and Free Will came to mind:

“...Let us imagine a person called upon to make a seemingly free decision under serious circumstances: we shall call him Peter. The question is whether a philosopher Paul, living at the same period as Peter, or, if you prefer, a few centuries before, would have been able, knowing all the conditions under which Peter acts, to foretell with certainty the choice which Peter made.”

“We find ourselves compelled, therefore, to alter radically the idea which we had formed of Paul: he is not, as we had thought at first, a spectator whose eyes pierce the future, but an actor who plays Peter's part in advance. And notice that you cannot exempt him from any detail of this part, for the most common-place events have their importance in a life-story; and even supposing that they have not, you cannot decide that they are insignificant except in relation to the final act, which, by hypothesis, is not given. Neither have you the right to cut short—were it only by a second—the different states of consciousness through which Paul is going to pass before Peter; for the effects of the same feeling, for example, go on accumulating at every moment of duration, and the sum total of these effects could not be realized all at once unless one knew the importance of the feeling, taken in its totality, in relation to the final act, which is the very thing that is supposed to remain unknown. But if Peter and Paul have experienced the same feelings in the same order, if their minds have the same history, how will you distinguish one from the other? Will it be by the body in which they dwell? They would then always differ in some respect, viz., that at no moment of their history would they have a mental picture of the same body. Will it be by the place which they occupy in time? In that case they would no longer be present at the same events: now, by hypothesis, they have the same past and the same present, having the same experience. You must now make up your mind about it: Peter and Paul are one and the same person, whom you call Peter when he acts and Paul when you recapitulate his history.”

This passage brings to light a very peculiar aspect of omniscience. I will try to show what I am talking about through a chain of thoughts.

If God is to be omniscient, God needs to have

I. Total knowledge of objective events

II. Total knowledge of subjective agents and their inner workings.

If God is to be the ultimate moral judge of an agent, God needs to have

I. Total knowledge of the moral consequences of every action of theirs.

II. Total knowledge of the internal moral motives of that agent for every action of theirs.

As Bergson demonstrates, choices in human life are a result of a qualitative multiplicity of preceding sensations, thoughts, events, etc. which can only be known through “becoming” the chooser via experiencing the exact same multiplicity of preceding sensations, thoughts, events, etc.

Thus, in order for God to obtain complete omniscience and moral authority, God would have to grasp the thought-history and sensation-history of every single acting agent, or else:

I. God would not obtain knowledge of all possible information (without regards to moral judgement).

II. God would not be able to perfectly judge a moral agent on the basis of a full consideration of consequences AND motives.

To me, these requirements of omniscience open up the following questions:

Could God be truly omniscient without being pantheistic/immanent in every person?

Why does Christianity conceive of Jesus Christ as the necessary experiential unity of God and Man, when omniscience dictates that God already has a complete understanding of the totality of subjective properties of every human life?

I am by no means a serious philosopher, nor am I particularly great deductive thinker, and would appreciate help thinking about/discussing this particular topic. Are there problems with this reasoning? Do the premises hold up?

#philosophy#short writing#writing#theosophy#theology#christianity#bergson#henri bergson#philosophical investigations#continental philosophy#original philosophy

2 notes

·

View notes