#Crying because the task force refused to work at the most crucial moment of production

Text

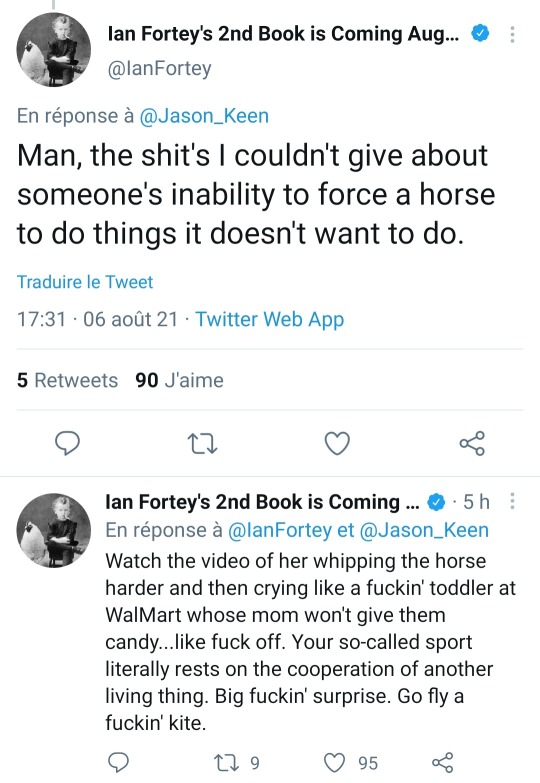

It was absolutely, absolutely horrible to watch this, and a good example of how we collectively choose to empathize with humans only, while the true victim is right before our eyes. The fear and abuse this horse was and is subjected to should never be called a sport. Forcing another sentient being to do things they don't want to do is never a sport. It is abuse, plain abuse people enjoy watching on TV. Then just imagine how horrible things must be when the cruelty has to be hidden.

#My cousin watches the Olympics and I had the misfortune to come down at the moment they were showing this#I had no words. It was disgusting from beginning to end.#Crying because the task force refused to work at the most crucial moment of production?#Olympics#JO#Veganism

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

[Unitierracalifas] UT Califas fierce care ateneo, 3-25-17, 2.00-5.00 p.m.

Compañerxs,

The Universidad de la Tierra Califas' Fierce Care Ateneo will gather on Saturday, March 25, from 2.00 - 5.00 p.m. at Miss Ollie's / Swans Market (901 Washington Street, Oakland, a few blocks from the 12th Street BART station) to continue our regular, open reflection and action space to explore questions and struggles related to the emerging politics of fierce care as well as some of the questions below.

Friday, March 10 ended Native Nations Rise, a four day convergence of Indigenous peoples and allies who gathered in Washington D.C. to continue the fight against the Dakota Access Pipeline as well as the several other pipelines under construction, including the Keystone XL, Trans-Pecos, Bayou Ridge, and Dakota Access. The fight, according to Kandi Mossett, is more than against one pipeline, it's about embracing a whole new way of life —one that is sustainable and is not about taking from the earth, but giving back. It is an on-going struggle. For Mossett and others it is the continuation of a five hundred year struggle against forces that take and destroy for a lifestyle that is no longer tenable. The four days of mobilization in D.C. not only confronted the destruction of shale deposits and the pipelines that the oil industry wants to use to maintain a toxic lifestyle, but also advanced a recognition that we must reclaim and invent a new, sustainable way of living. (see, Jaffe, "Next Steps in the Battle Against the Dakota Access and Keystone Pipelines")

More and more we are reminded that Indigenous communities are on the front lines of struggle. They are often the first line of defense against the rapacious and destructive extractive industries. It is this battle line that also signals that the U.S. is a settler colonial nation and as such has been and remains committed to erasing Indigenous people. The most recent persecution against the Standing Rock Sioux and others at the DAPL has made sacred site water protectors into targets of the most advanced militarized police repression, deploying sophisticated weaponry, infiltration, and surveillance while also criminalizing sacred-site water protectors in the mainstream media. The assault on Indigenous nations underscores the most critical element of settler colonialism, that is, according to Patrick Wolfe, it is "a structure, not an event." (see, Wolfe, "Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native") J. Kehaulani Kauanui takes up Wolfe's argument to point to an "enduring indigeneity" that operates dialectically as Indigenous peoples resist all elimination efforts, and at the same time as the settler colonial structure continues into the present to "hold out" against indigeneity. (See, J. Kehaulani Kauanui, "A Structure, Not an Event.") For both Wolfe and Kauanui, Palestine is the most recent site of a violent settler colonialism advanced by a U.S. backed Zionism. To this we would add Indian-occupied Kashmir, of which Omar Bashir recently noted, "India only wants Kashmir, not its people," thus naming the settler colonial logic with its concomitant operations of elimination and containment. (see, Bashir, "India Only Wants Kashmir, Not Its People")

More recently, Lorenzo Veracini has taken up Wolfe's intervention and also asserted that both the Indigenous and non-Indigenous are now being treated roughly the same —that is as disposable people. "The working poor are growing in number almost everywhere," warns Veracini. "Like Indigenous peoples facing a settler colonial onslaught, the 'expelled' are marked as worthless. The 'systemic transformation' produces modalities of domination that look like setter colonialism." In other words, more and more people are treated as disposable and the system would prefer to eliminate them rather than convert them into exploitable labor. (see, Veracini, "Settler Colonialism's Return")

From the Zapatistas to the several battle lines against pipelines across the U.S. and other battle fronts occupied by Indigenous communities across the globe, they are at the fore front of disrupting capitalism. But, it's not the capital(ism) we originally battled against. Or, at least, our understanding of capitalism has shifted, because capitalism has reached its final crisis. There are two clear areas of analysis that more recently have exposed its limits. First, capitalism no longer has access to an inexhaustible or "cheap nature." According to Jason Moore "capitalism is historically coherent —if 'vast but weak'— from the long sixteenth century; co-produced by a 'law of value' that is a 'law' of Cheap Nature. At the core of this law is the ongoing, radically expansive, and relentlessly innovative quest to turn work/energy of the biosphere into capital (value-in-motion)." (Moore, Capitalism in the Web of Life, p. 14)

Robert Kurz, and the wertkritik school that has been built around his work, is the second line of thought that recognizes capitalism is not just in yet another cyclical crisis but is nearing the limits of its internal contradiction. Kurz has taken to task the different approaches to Marx for their inability to extend Marx's critique of political economy and account for both the excesses and limits of commodity society. "Kurz, on the basis of a thoroughgoing reading of Marx," asserts Anselm Jappe, "maintained that the basic categories of the capitalist mode of production are currently losing their dynamism and have reached their 'historical limit': mankind no longer produces enough 'value.'" (see, Jappe, "Kurz: A Journey into Capitalism's Heart of Darkness," p. 397) The crucial point made by Kurz and elaborated by Jappe is that capitalism is not eternal, nor are the specific elements of capitalism, i.e., abstract labor, value, commodity, and money, timeless. "The structural mass of unemployment (other typical phenomena are dumping-wages, social welfare, people living in dumps, and related forms of destitution) indicates that the compensating historical expansionary movement of capital has come to a standstill." (see, Kurz, "Against Labour, Against Capital: Marx 2000") Kurz admonishes against mis-using Marx's categories and falling into a positivistic trap. A more complete reading and extension of Marx's insights reveal that commodity, value, and labor are not ontological, "transhistorical conditions of human existence." As much as they are neither eternal or timeless, they likewise have a history. "The appearance of labor as the substance of value is real and objective, but it is real and objective only within the modern commodity-producing system." Jappe explains,"Kurz always asserted that capitalism was disappearing along with its old adversaries, notably the workers' movement and its intellectuals who completely internalised labour and value and never looked beyond the 'integration' of workers —followed by other 'lesser' groups— into commodity society,"

Both Moore and Kurz invite us to interrogate the myth of capitalism as a never-ending system and to recognize that it has reached its limit. It can not overcome its internal contradictions given that it can no longer exploit cheap nature. But, if capitalism is gasping its last what does this mean for race and racial formations that were long believed to be essential to managing capitalism's most exploitative functions, i.e. producing surplus value via tightly controlled labor made more malleable through a brutal racial hierarchy of violent control? Does the end of capitalism signal an abandonment of the several intersecting racial regimes that helped insure its reproduction? "Race," Wolfe insists, "is colonialism speaking, in idioms whose diversity reflects the variety of unequal relationships into which Europeans have co-opted conquered populations." For Wolfe,"different racialising practices seek to maintain population-specific modes of colonial domination through time," (see, Wolfe, "Introduction," Traces of History, p. 5; 10) If settler colonialism endures as a structure that attempts to produce populations as disposable, how are we to understand this in relation to labor and race in the current moment?

Is disposability a condition of capital in its final stage or a new racial regime? "Disposability manifests," Martha Biondi reminds us, "in our larger society's apparent acceptance of high rates of premature death of young African Americans and Latinos." It is not only the school to prison pipeline, structural unemployment, and "high rates of shooting deaths" that produce disposability. (quoted in Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, From #Blacklivesmatter to Black Liberation, p. 16) It is also the way we think about water, health, and collective ways of being.

Indigenous struggles and the Black and Brown working class are and have been refusing disposability. This can be heard in the adamant battle cry proclaiming, Black lives matter! and also in the stands taken across the globe by Indigenous people and their supporters to protect the earth. Disposibility as a technology and extractivism as an operation are imbricated and proceed in violent unison as capital enters a new phase. Disposibility is marked by settler colonialism's "drive to elimination...[a] system of winner-take-all;" extractivism follows its own mandate of total depletion of all resources, also a system of grabbing everything. (Kauanui and Wolfe, "Settler Colonialism Then and Now")

Raul Zibechi analyzes the extractivist model as a new form of neoliberalism: "extractivism creates a dramatic situation —you might call it a campo without campesinos— because one part of the population is rendered useless by no longer being involved in production, by no longer being necessary to produce commodities." For Zibechi, "the extractivist model tends to generate a society without subjects. This is because there cannot be subjects within a scorched-earth model such as extractivism. There can only be objects." (see, Zibechi, "Extractivism creates a society without subjects") What does care look like at the end of capitalism? When we are longer bound by the relations of a commodity society?

South and North Bay Crew

NB: If you are not already signed-up and would like to stay connected with the emerging Universidad de la Tierra Califas community please feel free to subscribe to the Universidad de la Tierra Califas listserve at the following url <https://lists.resist.ca/cgibin/mailman/listinfo/unitierraca lifas>. Also, if you would like to review previous ateneo announcements and summaries please check out UT Califas web page. Additional information on the ateneo in general can be found at: <http://ccra.mitotedigital.org /ateneo>. Find us on tumblr at <https://uni-tierra-califas.tumblr.com>. Also follow us on twitter: @UTCalifas. Please note we will be shifting our schedule so that the Democracy Ateneo (San Jose) will convene on the fourth Saturday of every even month. The opposite, or odd month, will be reserved for the Fierce Care Ateneo (Oakland). In this way, we are making every effort to maintain an open, consistent space of insurgent learning and convivial research that covers both sides of the Bay.

--

Center for Convivial Research at Autonomy

http://ggg.vostan.net/ccra/#1

#Universidad de la Tierra Califas#Fierce Care Ateneo#Oakland#settler colonialism#Lorenzo Veracini#J. Kehaulani Kauanui#Patrick Wolfe#UniTierra Califas#UTC

1 note

·

View note

Photo

ON PROTEST + FOLK POLITICS / New Yorker

Smartphones and social media → supposed to have made organizing easier, and activists today speak more about numbers and reach than about lasting results...

Is protest a productive use of our political attention? Or is it just a bit of social theatre we perform to make ourselves feel virtuous, useful, and in the right?

Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams → question the power of marches, protests, and other acts of what they call “folk politics” → These methods are more habit than solution...

Protest is too fleeting → ignores the structural nature of problems in a modern world: “The folk-political injunction is to reduce complexity down to a human scale.” This impulse promotes authenticity-mongering, reasoning through individual stories, and a general inability to think systemically about change...

In the immediate sense, a movement such as Occupy wilted because police in riot gear chased protesters out of their spaces → But, really, its methods sank it from the start by channeling the righteous sentiments of those involved over the mechanisms of real progress.

“This is politics transmitted into pastime—politics-as-drug-experience, perhaps—rather than anything capable of transforming society.”

The left (despite its pride in being progressive) is mired in nostalgia → Petitions, occupations, strikes, vanguard parties, affinity groups, trade unions: all arose out of particular historical conditions...

According to the classical model of protest, strategy (the big idea, the master plan) falls to a movement’s leaders, while tactics (the moves you make, the signs you wave, the action in the street) fall to the people on the ground → One of Hardt and Negri’s cornerstone ideas is that the formula should be flipped: strategy goes to the movement masses, tactics to the leadership. In theory, this allows movements to stay both nimble (an emergency on the ground is when you call in the brass) and on guard against autocracy (no group can decide for the many).

Folk politics → prefers that actions be taken by participants themselves (in its emphasis on direct action, for example) and sees decision-making as something to be carried out by each individual rather than by any representative

“Sometimes you protest just to register a public objection to policies you have no hope of changing.” Movements might have lost their leaders, gained force, and offered personal autonomy. Yet they hadn’t acquired the crucial thing—a good crack at success.

Tufekci → believes that digital-age protests are not simply faster, more responsive versions of their mid-century parents → They are fundamentally distinct. At Gezi Park, she finds that nearly everything is accomplished by spontaneous tactical assemblies of random activists—the Kauffman model carried further through the ease of social media. “Preexisting organizations whether formal or informal played little role in the coordination,” she writes. “Instead, to take care of tasks, people hailed down volunteers in the park or called for them via hashtags on Twitter or WhatsApp messages.” She calls this style of off-the-cuff organizing “adhocracy”

Today anyone can gather crowds through tweets, and update, in seconds, thousands of strangers on the move. At the same time, she finds, shifts in tactics are harder to arrange. Digital-age movements tend to be organizationally toothless, good at barking at power but bad at forcing ultimatums or chewing through complex negotiations.

The missing ingredients, Tufekci believes, are the structures and communication patterns that appear when a fixed group works together over time. That practice puts the oil in the well-oiled machine. It is what contemporary adhocracy appears to lack, and what projects such as the postwar civil-rights movement had in abundance. And it is why, she thinks, despite their limits in communication, these earlier protests often achieved more.

Tufekci describes weeks of careful planning behind the yearlong Montgomery bus boycott, in 1955 → That spring, a black fifteen-year-old named Claudette Colvin refused to give up her seat on a bus and was arrested. Today, though, relatively few people have heard of Claudette Colvin. Why? Drawing on an account by Jo Ann Robinson, Tufekci tells of the Montgomery N.A.A.C.P.’s shrewd process of auditioning icons. “Each time after an arrest on the bus system, organizations in Montgomery discussed whether this was the case around which to launch a campaign,” she writes. “They decided to keep waiting until the right moment with the right person.” Eventually, they found their star: an upstanding, middle-aged movement stalwart who could withstand a barrage of media scrutiny. This was Rosa Parks.

What is striking about the bus boycott is not so much its passion, which is easy to relate to, as its restraint, which (at this moment, especially) is not! No outraged Facebook posts spread the news when Colvin was arrested. Local organizers bided their time, slowly planning, structuring, and casting what amounted to a work of public theatre, and then built new structures as their plans changed. The protest was expressive in the most confected sense, a masterpiece of control and logistics. It was strategic, with the tactics following. And that made all the difference in the world.

Tufekci’s conclusions about the civil-rights movement are unsettling because of what they imply. People such as Kauffman portray direct democracy as a scrappy, passionate enterprise: the underrepresented, the oppressed, and the dissatisfied get together and, strengthened by numbers, force change. → Tufekci suggests that the movements that succeed are actually proto-institutional: highly organized; strategically flexible, due to sinewy management structures; and chummy with the sorts of people we now call élites. The Montgomery N.A.A.C.P. worked with Clifford Durr, a patrician lawyer whom Franklin Roosevelt had appointed to the F.C.C., and whose brother-in-law Hugo Black was a Supreme Court Justice when Browder v. Gayle was heard. The organizers of the March on Washington turned to Bobby Kennedy—the U.S. Attorney General and the brother of the sitting President—when Rustin’s prized sound system was sabotaged the day before the protest. Kennedy enlisted the Army Signal Corps to fix it. You can’t get much cozier with the Man than that. Far from speaking truth to power, successful protests seem to speak truth through power.

And it forces one to reassess the rise of well-funded “Astroturf” movements such as the Tea Party: successful grassroots lawns, it turns out, have a bit of plastic in them, too. → Democratizing technology may now give the voiceless a means to cry in the streets, but real results come to those with the same old privileges (time, money, infrastructure, an ability to call in favors) that shape mainline politics.

Hardt and Negri, as well as Srnicek and Williams, rail at length against “neoliberalism”: a fashionable bugaboo on the left, and thus, unfortunately, a term more often flaunted than defined.

Srnicek and Williams don’t reject working with politicians, though they think that real transformation comes from shifts in social expectation, in school curricula, and in the sorts of things that reasonable people discuss on TV (the so-called Overton window). It’s an ambitious approach but not an outlandish one: Bernie Sanders ran a popular campaign, and suddenly socialist projects were on the prime-time docket. Change does arrive through mainstream power, but this just means that your movement should be threaded through the culture’s institutional eye.

The question, then, is what protest is for. Srnicek and Williams, even after all their criticism, aren’t ready to let it go → they describe it as “necessary but insufficient.”

A truly modern left, one cannot help but think, would be at liberty to shed a manufacturing-era, deterministic framework like Marxism, allegorized and hyperextended far beyond its time → Still, to date no better paradigm for labor economics and uprising has emerged...

What comes undone → the dream of protest as an expression of personal politics. Those of us whose days are filled with chores and meetings may be deluding ourselves to think that we can rise as “revolutionaries-for-a-weekend”(Norman Mailer’s phrase for his own bizarre foray, in 1967, as described in “The Armies of the Night.”)

If that seems a deflating idea, it only goes to show how entrenched self-expressive protest has become in political identity...

0 notes