#Daniel Gélin

Photo

Simone Simon and Daniel Gélin in Le Plaisir (Max Ophüls, 1952)

Cast: Claude Dauphin, Gaby Morlay, Madeleine Renaud, Ginette Leclerc, Mila Parély, Danielle Darrieux, Pierre Brasseur, Jean Gabin, Jean Servais, Daniel Gélin, Simone Simon, Paul Azaïs. Screenplay: Jacques Natanson, Max Ophüls, based on stories by Guy de Maupassant. Cinematography: Philippe Agostini, Christian Matras. Production design: Jean d’Aubonne. Film editing: Léonide Azar. Music: Joe Hajos.

Pleasure, as the poets never tire of telling us, is inextricable from pain. Le Plaisir is an anthology film dramatizing three stories by Guy de Maupassant that center on what has been called the pleasure-pain perplex. An elderly man nearly dances himself to death in an attempt to recapture his youth. The patrons of a brothel quarrel and even come to blows when they discover that it is closed. An artist marries his mistress to atone for his cruelty to her. Max Ophüls brings all of his elegant technique to the stories, including his characteristic restless camera, which prowls around the wonderful sets by Jean d'Eaubonne, who received a well-deserved Oscar nomination for art direction. It's also, like Ophuls's La Ronde (1950), an all-star production -- if your stars are French. Claude Dauphin plays the doctor who treats the youth-seeking dancer; Madeleine Renaud is the madame of the brothel, Danielle Darrieux is one of her "girls," and Jean Gabin plays the madame's brother, who invites her to bring the girls to the country for his daughter's first communion, hence the temporary closure of the brothel; Daniel Gélin is the artist, Simone Simon his model/mistress, and Jean Servais his friend who also narrates the final section. Of the three segments of the film, the middle one is the longest and I think the most successful, moving from the raucous opening scene in which the men of the small Normandy town discover the brothel closed into a comic train ride to the country, which is as fetchingly pastoral a setting as you could wish. The sequence climaxes with the filles de joie dissolving in tears at the first communion -- the little church in which it takes place is one of d'Eaubonne's most inspired sets -- then returning to town and a joyous welcome. Ophuls never lets us inside the brothel: We see it only as voyeurs, through the windows. Nothing of this segment is "realistic" in the least, making the melancholy first and last segments more important in establishing the film's theme and tone. The first segment does its part to set up the course of the film as a whole, beginning with a riotous opening as tout Paris flocks to the opening of a dance hall, a pleasure palace, followed by scenes of lively dancing, then the collapse of the elderly patron, who is wearing a frozen and rather creepy mask of youth, and concluding with the bleakness of his normal existence, tended by his aging wife, who is fittingly played by Gaby Morlay, once a silent film gamine. The final segment is the bleakest of all, as the film concludes with the artist pushing his wheelchair-bound wife along the seashore, penance for having provoked her suicide attempt.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

si seulement vous saviez .

#daniel gélin#mon grand-père#jvais pas taguer son nom pour soucis de vie privée tho#mais#la jalousie#c’est ce que gélin a vécu avec mon grand-père

4 notes

·

View notes

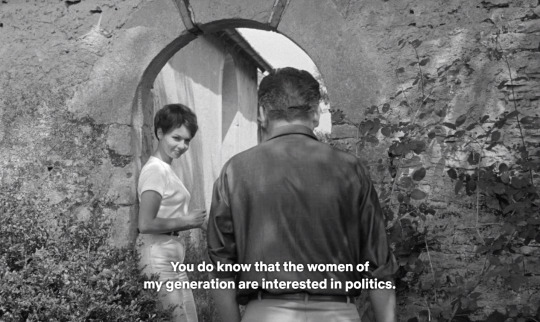

Photo

You know how it goes. Contempt has always followed possession. To spend your whole life with someone, you don't need lust - which is quickly extinguished - but a harmony of minds, temperaments, and humor.

Le Plaisir, Max Ophüls (1952)

#Max Ophüls#Jacques Natanson#Claude Dauphin#Gaby Morlay#Madeleine Renaud#Ginette Leclerc#Mila Parély#Danielle Darrieux#Pierre Brasseur#Jean Gabin#Jean Servais#Daniel Gélin#Simone Simon#Philippe Agostini#Christian Matras#Joe Hajos#Léonide Azar#1952

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

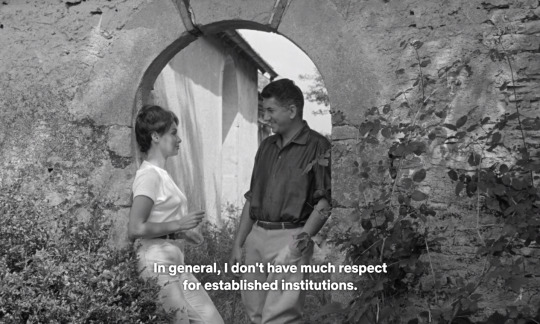

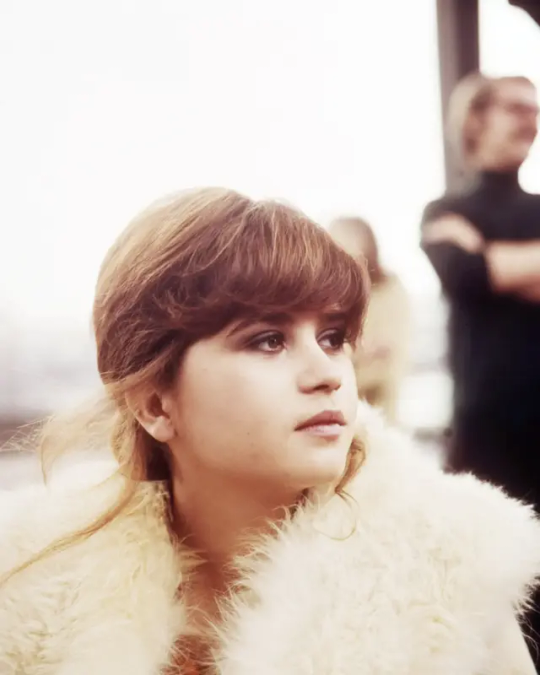

La Morte-Saison des Amours, dir. Pierre Kast (1961)

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

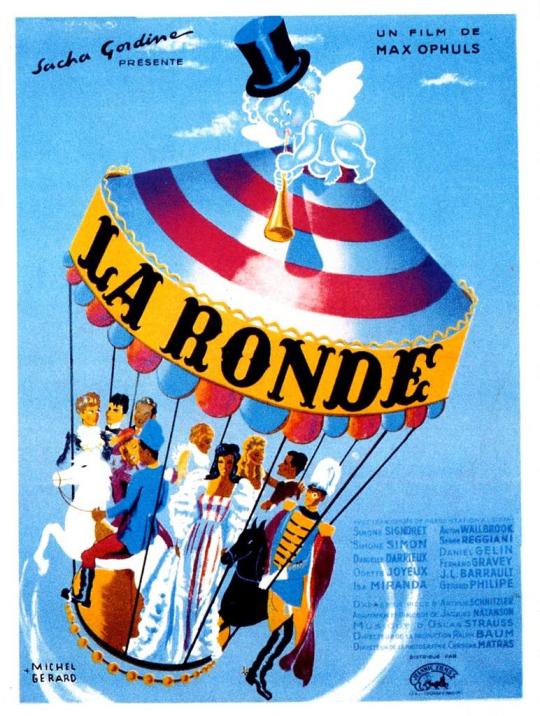

Films Watched in 2022:

68. La Ronde (1950) - Dir. Max Ophüls

#La Ronde#Max Ophüls#Anton Walbrook#Simone Signoret#Serge Reggiani#Simone Simon#Daniel Gélin#Fernand Gravey#Gérard Philipe#Danielle Darrieux#Jean-Louis Barrault#Odette Joyeux#Isa Miranda#Films Watched in 2022#My Edits#My Post

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

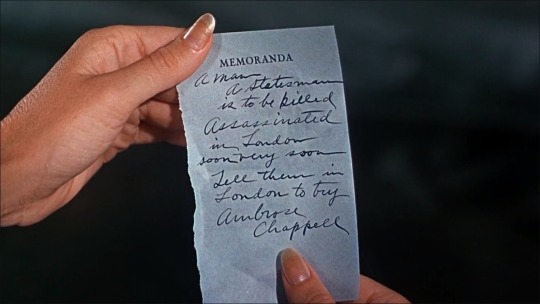

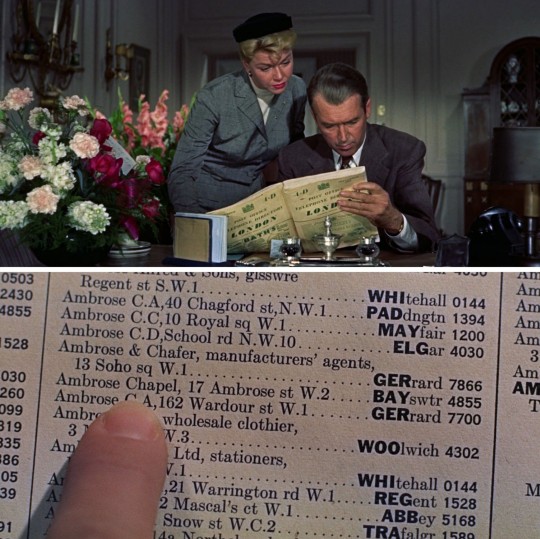

"The Man Who Knew Too Much" (1956) - Alfred Hitchcock

Films I've watched in 2022 (83/210)

#films watched in 2022#The Man Who Knew Too Much#Doris Day#James Stewart#Christopher Olsen#Daniel Gélin#Reggie Nalder#Alan Mowbray#Hillary Brooke#Alix Talton#Carolyn Jones#Alfred Hitchcock

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#the man who knew too much#james stewart#doris day#brenda de banzie#bernard miles#christopher olsen#daniel gélin#reggie nalder#alfred hitchcock#1956

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unter der kompetenten Leitung der Herren Ophüls und Walbrook dreht sich Schnitzlers Reigen ganz besonders schön, nur zwischen dem jungen Herrn und der verheirateten Frau hapert es kurz. Das war jetzt auch mal wieder nötig.

#La ronde#Anton Walbrook#Simone Signoret#Serge Reggiani#Simone Simon#Daniel Gélin#Danielle Darrieux#Fernand Gravey#Odette Joyeux#Jean-Louis Barrault#Ida Miranda#Gérard Philippe#Film gesehen#Max Ophüls#Arthur Schnitzler

1 note

·

View note

Text

29 novembre … ricordiamo …

29 novembre … ricordiamo …

#semprevivineiricordi #nomidaricordare #personaggiimportanti #perfettamentechic

2021: Arlene Dahl, Arlene Carol Dahl, attrice e modella statunitense. Di origini norvegesi, i genitori Idelle Swan e Rudolph S. Dahl, dirigente della Ford. Incoraggiata dalla madre, appassionata di teatro, la Dahl iniziò presto a prendere lezioni di recitazione e di danza, partecipando a rappresentazioni amatoriali scolastiche. Durante gli studi superiori presso la Washburn High School, continuò…

View On WordPress

#29 novembre#Alessandro Ruffini#Archibald Alexander Leach#Arlene Carol Dahl#Arlene Dahl#Cary Grant#Daniel Gélin#Daniel Yves Alfred Gélin#Eduardo Scarpetta#Emilio Pucci#Fernando Bonora#Fernando Farese#Frank Kline#Frank Latimore#Gianfranco Giachetti#Herbert Marx#John Drew Barrymore#John Mitchum#John Newman Mitchum#Margaret L. Murray#Mario Monicelli#Morti 29 novembre#Natal&039;ja Nikolaevna Zacharenko#Natalie Wood#Peg Murray#Sandro Ruffini#Zeppo Marx

0 notes

Text

ÉDOUARD ET CAROLINE (1951) / RUE DE L'ESTRAPADE (1953) - Jacques Becker

Après un détour par les milieux prolétaires (Antoine et Antoinette) et intellectuels (Rendez-vous de juillet), Jacques Becker réussit au début des années 1950 deux comédies légères sur la bourgeoisie qui s’imposent en équivalents français des comédies de Hawks et Lubitsch : Edouard et Caroline et Rue de l’estrapade, toutes deux interprétées par Daniel Gélin et la délicieuse Anne Vernon, dont se…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Daniel Gélin in Edward and Caroline (1951)

175 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Benoît Ferreux, Ave Ninchi, Lea Massari, and Daniel Gélin in Murmur of the Heart (Louis Malle, 1971)

Cast: Benoît Ferreux, Lea Massari, Daniel Gélin, Fabien Ferreux, Marc Winocourt, Ave Ninchi, Michael Lonsdale, Jacqueline Chauvaud, Corinne Kersten, Gila von Weitershausen. Screenplay: Louis Malle. Cinematography: Ricardo Aronovich. Production design: Jean-Jacques Caziot.

There's a very dated play from 1953 called Tea and Sympathy by Robert Anderson that was made into an even more dated film by Vincente Minnelli in 1956 about a prep-school boy whose effeminacy makes him the target for gibes about homosexuality. To prove to the boy that he's a real man (i.e., not gay), the headmaster's wife offers herself sexually to the boy, telling him as she unbuttons her blouse and the curtain falls, "Years from now, when you speak of this, and you will, be kind." The film version, responding to Production Code strictures, adds a coda in which we learn that the boy is now married -- i.e., "cured." I thought of Tea and Sympathy as I watched Murmur of the Heart, whose very different problem -- adolescent horniness -- has a very different cure -- incest. Murmur of the Heart has always been something of a critical darling, from Pauline Kael's description of it as an "exhilarating high comedy" to Michael Sragow's essay for the Criterion Collection proclaiming that it "boasts the high spirits to match its high intelligence." And for the most part I concur: Lea Massari's joyously earthy performance as the mother is beautifully detailed, and Benoît Ferreux's endearing gawkiness brings the character of Laurent to full life. Louis Malle's script and direction keep things moving splendidly, never allowing things to bog down into "message moments" about priestly pedophilia -- years before that became the stuff of headlines -- or the parallels between the French involvement in Vietnam and that of the Americans, which was very much in the headlines when the film was made. And yet for me the ending of Murmur of the Heart seems as hollow as that of Tea and Sympathy. After having sex with his mother, the product of his attempt to console her for a breakup with her lover, he goes out to have sex with one of the girls he has met at the spa hotel where they're staying -- as if to prove that he's "straight," though in a different way from that of the Tea and Sympathy protagonist. There's an awkwardness in the setup -- the shocking taboo of incest -- for what turns into a feel-good ending gag: The whole family, including the mother, the cuckolded father, the bullying older brothers, and Laurent himself, join in uproarious laughter at the fact that Laurent has gotten laid. If what had gone before the incest scene had not been so splendidly wrought -- if, in fact, the incest scene itself hadn't been so tastefully handled -- would we really feel satisfied with this ending? For that matter, are we today really content with the film's ongoing sexism, including the scene with Laurent in the brothel and an uncommonly pretty prostitute? Would anyone ever dare to make a comedy that concluded with a girl whose quest to lose her virginity ends with her having sex with her father? Or is it that what makes Murmur of the Heart a successful film is that it raises all these questions without belaboring us with them? It's a virtual catalog of all of the social and sexual hangups that continue to make growing up such a trial. That it achieves this with, yes, "high spirits" and without preachiness may be its real virtue.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"La Ronde" de Max Ophüls - d'après la pièce de théâtre éponyme d'Arthur Schnitzler (1897) - avec Anton Walbrook, Simone Signoret, Gérard Philipe, Danielle Darrieux, Jean-Louis Barrault, Daniel Gélin, Odette Joyaux, Serge Reggiani, Simone Simon, Fernand Gravey ete Isa Miranda, mars 2024.

#films#spirit#fairies#Ophuls#Schnitzler#Walbrook#Signoret#Philipe#Darrieux#Barrault#Gelin#Joyeux#Reggiani#Simon#Gravey#Miranda

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Don't you realize that Americans dislike having their children stolen?

The Man Who Knew Too Much, Alfred Hitchcock (1956)

#Alfred Hitchcock#John Michael Hayes#James Stewart#Doris Day#Brenda de Banzie#Bernard Miles#Ralph Truman#Daniel Gélin#Mogens Wieth#Alan Mowbray#Hillary Brooke#Christopher Olsen#Reggie Nalder#Robert Burks#Bernard Herrmann#George Tomasini#1956

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Napoléon par Sacha Guitry, 1955. First Consul Bonaparte shows up at the opera and they burst into Le Chant du Départ. Daniel Gélin as Bonaparte.

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

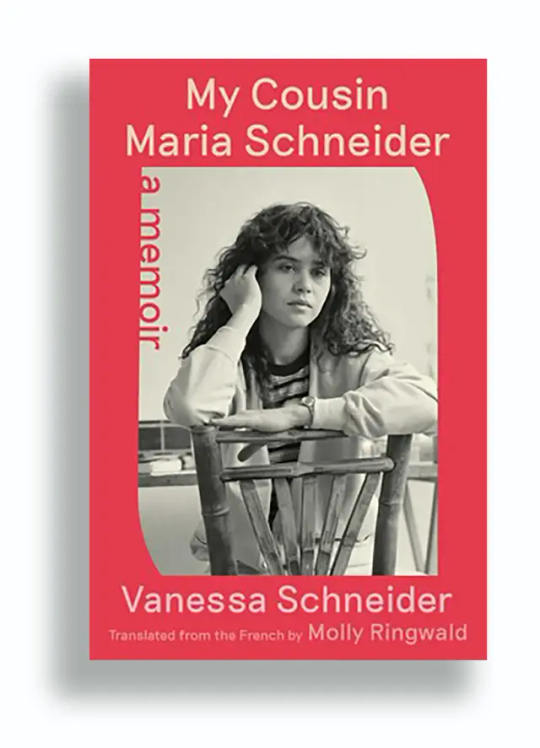

For ‘Last Tango’ Actress, the Ugly Aftermath of Notoriety

In a troubling new memoir, Vanessa Schneider contends that the sexually explicit 1972 film exploited, and irrevocably hurt, her cousin.

Maria Schneider in a scene from the 1972 film “Last Tango in Paris.”

Credit...Silver Screen Collection/Getty Images

By Thessaly La Force

Published April 16, 2023

Updated May 24, 2023

MY COUSIN MARIA SCHNEIDER: A Memoir, by Vanessa Schneider. Translated by Molly Ringwald.

For many actresses, the path of the ingénue can be treacherous. Celebrated for her beauty and youth, the ingénue is defined almost exclusively by her sexuality. An outsize amount of attention is paid to her looks and her body, little interest to her mind. As she grows older, opportunities diminish. Forced to act younger than her age and compete with newer faces, she eventually discovers that her career has hit a dead end. Among the long list of cautionary tales: Jean Seberg, the darling of French New Wave cinema, who died by suicide at the age of 40; Debra Winger, who shocked Hollywood by retiring at the height of her fame at 40; and, of course, the French actress Maria Schneider.

Schneider was only 20 years old when she catapulted to fame after starring opposite Marlon Brando in Bernardo Bertolucci’s 1972 film “Last Tango in Paris.” In its most notorious scene, Brando, who plays a grief-stricken man named Paul, rapes Schneider, who plays a young woman named Jeanne, improvising with butter as a lubricant. Bertolucci and Brando conspired to film the scene, which Schneider claimed wasn’t in the original script, without her consent. Bertolucci later explained his reason for that decision as wanting Schneider “to respond like a girl, not an actress.”

Because of its violence and frank treatment of sex, the film was a sensation, confirming Bertolucci’s status as a provocative filmmaker and cementing the comeback of Brando, who for some time had been seen as a Hollywood has-been.

For Schneider, it was her “cross to bear,” writes the French journalist and novelist Vanessa Schneider in “My Cousin Maria Schneider,” a slender memoir composed in second person, directly addressed to the actress and elegantly translated from the French by Molly Ringwald. The book, first published in 2018 in France, is both a beautiful eulogy (Schneider died of lung cancer in 2011) and a much-needed corrective — an opportunity to finally set the record straight for an actress long mischaracterized and unfairly judged.

The “Last Tango” scene would define Schneider for the rest of her life, explains Vanessa Schneider. Subjected to unrelenting negative publicity and attention surrounding it (a dairy manufacturer once used Schneider’s image on its packaging; a flight attendant served her a pat of butter without prompting), Schneider acted out. She spoke too candidly to the press about her personal life; she dismissed famous directors and actors; she walked off film sets.

That Schneider was also addicted to heroin didn’t help, and Vanessa Schneider wonders if the drugs and partying were ways to avoid the spotlight so instantly thrust on the young actress.

Growing up, Maria Schneider was unwanted. Her father, the French actor Daniel Gélin, was not involved in her childhood, and her mother, Marie-Christine Schneider, sent Schneider to live with a nursemaid when she was 8. Her mother’s “sex life was never a secret,” writes Vanessa Schneider. “A story often told … is of the time your mother was in bed with a man and called out for you to fetch her diaphragm.” She also reveals that Schneider’s mother “elected not to take the trip from Nice to Paris” for her daughter’s funeral, “saying she was too tired.”

Vanessa Schneider’s parents took in Maria as a teenager. From an early age, Vanessa worshiped her older cousin, saving every clipping of her from magazines and newspapers in a red plastic binder. As a result, this memoir is written with a rare sense of intimacy and devotion. It warmly captures the highlights of Maria Schneider’s life: her enduring friendships with Brigitte Bardot and Nan Goldin, her pride in starring in films such as Michelangelo Antonioni’s “The Passenger” and her later advocacy for women in film.

It is also, at moments, unsparing, describing Schneider’s struggles with addiction, financial woes and other embarrassing family drama. At one point Vanessa Schneider questions whether her cousin would like such an unvarnished portrayal of her life, and deletes what she’s written. “I often worry that you won’t approve of the story I’m telling, Maria,” she explains. “You won’t like that I’m speaking of the drugs, of your mother and father and brothers.”

Yet in this post-#MeToo era, Vanessa Schneider’s evenhanded portrayal of this daring actress of the 1970s is a refreshing one. For once, a young woman is not placed on an impossibly high pedestal, where she is unfairly worshiped for her beauty and then cruelly defiled for our entertainment. Instead, Maria Schneider is presented with both her faults and her charms. In that way, this is a generous account of a rare and complicated cinematic star.

Thessaly La Force is a freelance writer and frequent contributor to The New York Times Styles section. Previously, she was the features director at T: The New York Times Style Magazine.

MY COUSIN MARIA SCHNEIDER: A Memoir | By Vanessa Schneider | Translated by Molly Ringwald | 160 pp. | Scribner | $26

#The New York Times#Thessaly La Force#The Last Tango in Paris#Bernardo Bertolucci#Marlon Brando#Maria Schneider#Vanessa Schneider#Molly Ringwald#Tu t'appelais Maria Schneider

4 notes

·

View notes