#Economy of the Unlost: (Reading Simonides of Keos with Paul Celan)

Text

anne carson, economy of the unlost (reading simonides of keos with paul celan), 1999

#just started reading this lol but had to save this bc wow.#i have to read paul celan now.#anne carson#on fathers#encrypted files

164 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Homer said we ride into the future facing the past. Maybe the simplest prophecy is that we have made it this far. (“Trust the hours. Haven’t they / carried you everywhere, up to now?” writes Galway Kinnell.) In Economy of the Unlost, Anne Carson’s meditation on two other lyric poets, Paul Celan and Simonides of Keos, she puts it this way: “a poet is someone who traffics in survival.”

Anna Badkhen, from her essay “How to Read the Air”, published in The Paris Review, November 3, 2020

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

The word Geschwätz is a common German term for everyday chitchat. But Felstiner suggests it may have for Celan “hints of Babel and the loss of original language.” He explains:

For in Walter Benjamin’s essay “On Language in General and on the Language of Man,” Geschwätz designates empty speech after the Fall, speech without Adam’s power of naming... The babbling of Celan’s Jews is a comedown—via the cataclysm that ruined Benjamin—from God-given speech.

— Anne Carson, Economy of the Unlost: (Reading Simonides of Keos with Paul Celan)

#m#John Felstiner#Walter Benjamin#On Language in General and on the Language of Man#Paul Celan: Poet Survivor Jew#Gespräch im Gebirg#Paul Celan#Anne Carson#Economy of the Unlost#Economy of the Unlost: (Reading Simonides of Keos with Paul Celan)#Simonides of Keos#nonfiction#Babel#language#lost language

62 notes

·

View notes

Link

Proyecto de traducción de Economy of the Unlost (Reading Simonides of Keos with Paul Celan) de Anne Carson, realizado por Nicolás López Pérez. La entrada corresponde –la única hasta el momento publicada por el traductor– a «Notas sobre el método».

0 notes

Text

Economy of the Unlost by Anne Carson

The ancient Greek lyric poet Simonides of Keos was the first poet in the Western tradition to take money for poetic composition. From this starting point, Anne Carson launches an exploration, poetic in its own right, of the idea of poetic economy. She offers a reading of certain of Simonides' texts and aligns these with writings of the modern Romanian poet Paul Celan, a Jew and survivor of the Holocaust, whose "economies" of language are notorious. Asking such questions as, What is lost when words are wasted? and Who profits when words are saved? Carson reveals the two poets' striking commonalities.

In Carson's view Simonides and Celan share a similar mentality or disposition toward the world, language and the work of the poet. Economy of the Unlost begins by showing how each of the two poets stands in a state of alienation between two worlds. In Simonides' case, the gift economy of fifth-century b.c. Greece was giving way to one based on money and commodities, while Celan's life spanned pre- and post-Holocaust worlds, and he himself, writing in German, became estranged from his native language. Carson goes on to consider various aspects of the two poets' techniques for coming to grips with the invisible through the visible world. A focus on the genre of the epitaph grants insights into the kinds of exchange the poets envision between the living and the dead. Assessing the impact on Simonidean composition of the material fact of inscription on stone, Carson suggests that a need for brevity influenced the exactitude and clarity of Simonides' style, and proposes a comparison with Celan's interest in the "negative design" of printmaking: both poets, though in different ways, employ a kind of negative image making, cutting away all that is superfluous. This book's juxtaposition of the two poets illuminates their differences--Simonides' fundamental faith in the power of the word, Celan's ultimate despair--as well as their similarities; it provides fertile ground for the virtuosic interplay of Carson's scholarship and her poetic sensibility.

#ooc:// resources / all#ooc:// resources / texts#[ i don't know if i'll find any use of this but it's worth a shot ]#** anne carson

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Anne Carson's ECONOMY OF THE UNLOST (Reading Simonides of Keos w/ Paul Celan).

0 notes

Text

Gratitude and memory go together, morally and philologically. Paul Celan locates memory, in his Bremen speech, in an etymological link between thinking and thanking:

Denken und Danken sind in unserer Sprache Worte ein und desselben Ursprungs. Wer ihrem Sinn folgt, begibt sich in den Bedeutungsbereich von: “gedenken,” “engedenk sein,” “Andenken,” “Andacht.”

[To Think and to Thank are in our language words of one and the same origin. Whoever follows their sense comes to the semantic field of “to remember,” “to be mindful,” “memory,” “devotion.”]

For the Greeks, memory is rooted in utterance, if we may judge from the etymology of the noun μνήμη (“memory”), which is cognate with the verb μιμνήσκομαι (“I remember,” “I make mention,” “I name”), and from the genealogy of the goddess Mnemosyne, who is called “mother of the Muses” by Homer and Hesiod. Memorable naming is the function of poetry, within a society like that of the Greeks, for the poet uses memory to transform our human relationship to time. Had Simonides not named their names, the Skopads would have vanished into the past.

— Anne Carson, Economy of the Unlost: (Reading Simonides of Keos with Paul Celan)

#m#Paul Celan#Anne Carson#Economy of the Unlost#Economy of the Unlost: (Reading Simonides of Keos with Paul Celan)#Simonides of Keos#nonfiction#The Bremen Speech#memory#speech#Homer#Hesiod

4 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Celan is a poet who uses language as if he were always translating.

Anne Carson, Economy of the Unlost: (Reading Simonides of Keos with Paul Celan)

#m#Paul Celan#Anne Carson#Economy of the Unlost#Economy of the Unlost: (Reading Simonides of Keos with Paul Celan)#nonfiction#On Translation

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The ideal of this contract is clear: the Skopads sustain Simonides on earth, he sustains them in memory. An exchange of life for life. Of mortal for immortal continuance. You might think it a delicate matter to price such a commodity. Cicero gives us a more realistic picture of how Skopas went about it:

Once Simonides was dining at Krannon in Thessaly at the house of the rich and noble Skopas. He had composed a song in honor of this man and in it he put a lot of typical ornamental material concerning Kastor and Polydeukes. Whereat Skopas ungenerously declared that he would pay Simonides only half the fee they had agreed on for the song: the other half he should get from the gods whom he had praised to that extent. Just then Simonides received a message that two young men were asking for him at the front door on a matter of urgent business. He got up and went out but found no one there. Meanwhile the roof of the room in which Skopas was dining collapsed, killing him and his friends. Now when the kinsfolk of these people wished to bury them, they found it impossible to recognize the remains. But Simonides, it is said, by remembering the exact place where each man had sat at the table, was able to identify them all for burial. From this he discovered that it is order that mainly contributes to memory its light. . . . I am grateful to Simonides of Keos who thus invented (so they say) the art of memory.

“The anecdote quivers with allegory throughout, but especially when Cicero says, “I am grateful” (gratiam habeo). His word for gratitude is gratia (χάρις in Greek, “grace” in English). Let us take it as referring to the whole fund of grace that flows back and forth between a poet and his world. Simonides’ salvific action—both the particular act of remembering certain names and the wider gift of an ars memoria to the world—is a paradigm of what the poet does in confrontation with void. He thinks it and he thanks it, we could say (borrowing a phrase from Paul Celan’s Bremen speech), for it is the beginning of an immeasurable moment of value. Skopas mistook this and halved Simonides’ fee, as if to insist that poetic action has an exact equivalent in cash. We may read a degree of divine disapproval in the collapse of the roof and appearance of the Dioskouroi at the door. And here the allegory takes a wry turn. For the Dioskouroi are gods who know better than anyone else the cost of halving.

— Anne Carson, Economy of the Unlost: (Reading Simonides of Keos with Paul Celan)

#m#Paul Celan#Anne Carson#Economy of the Unlost#Economy of the Unlost: (Reading Simonides of Keos with Paul Celan)#Simonides of Keos#nonfiction#Cicero#The Bremen Speech#gratitude#memory

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Strangeness for Celan arose out of language and went back down into language. The problem of translation has a special instance in him. For he lived in exile in Paris most of his life and wrote poetry in German, which was the language of his mother but also the language of those who murdered his mother. Born in a region of Romania that survived Soviet, then German, occupation, he moved to France in 1948 and lived there till his death. “As for me I am on the outside,” he once said. I don’t think he meant by this (only) that he was a Romanian Jew with a French passport and a Christian wife, living in Paris and writing in German. But rather that, in order to write poetry at all, he had to develop an outside relationship with a language he had once been inside. He had to reinvent German on the screen of itself, by treating his native tongue as a foreign language to be translated— into German. As Pierre Joris says, “German was . . . in an essential way, his other tongue. . . . Celan is estranged from that which is most familiar.” Nonetheless it was important to Celan to keep on in German. This passage from a speech he gave in Bremen has often been quoted:

Reachable, near and unlost amid the losses, this one thing remained: language. This thing, language, remained unlost, yes, in spite of everything. But it had to go through its own loss of answers, had to go through terrifying muteness, had to go through the thousand darknesses of deathbringing talk. It went through and gave no words for that which happened; yet it went through this happening. Went through and was able to come back to light “enriched” by it all.

In this language I have tried, during those years and the years after, to write poems. . .

Most critics hear in “thousand darknesses of deathbringing talk” a reference to the linguistic forms and usages of the Nazi regime. As Felstiner says:

For the Thousand-Year Reich organized its genocide of European Jewry by means of language: slogans, pseudo-scientific dogma, propaganda, euphemism, and the jargon that brought about every devastating “action” from the earliest racial “laws” through “special treatment” in the camps to the last “resettlement” of Jewish orphans.

Surely the Nazis brought more death to the language than anyone else in its history. For Celan, to keep on in German despite this fact became the task of a lifetime. There is some suggestion, in a piece of prose he wrote in 1948 called “Edgar Jené and the Dream about the Dream,” that he sometimes saw language-death as a more universal problem: the tendency of meanings to “burn out” of language and to be covered over by a “load of false and disfigured sincerity” is one that he here ascribes to “the whole sphere of human communicative means.” But let us note that he qualifies the phrase “load of false and disfigured sincerity” with an adjective, tausendjährigen (“thousand-year-long”), that combines an indefinite term for “age-old” with a glance at the Christian millennium and a reference to the Nazis in their fifteen minutes of fame. For Celan, I think, no philosophizing about language could escape this latter reference. It gives a context of “ashes” to everything he says.

— Anne Carson, Economy of the Unlost: (Reading Simonides of Keos with Paul Celan)

#m#Pierre Joris#John Felstiner#Paul Celan#Anne Carson#Economy of the Unlost#Economy of the Unlost: (Reading Simonides of Keos with Paul Celan)#nonfiction#The Bremen Speech#language#exile#otherness#alienation

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Klein goes on to describe a landscape as impressive as the wild sea where Danaë is stranded:

Es hat sich die Erde gefaltet hier oben, hat sich gefaltet einmal und zweimal und dreimal, und hat sich aufgetan in der Mitte, und in der Mitte steht ein Wasser, und das Wasser ist grün, und das Grüne ist weiß, und das Weiße kommt von noch weiter oben, kommt von den Gletschern...

[Up here the earth has folded over, it’s folded once and twice and three times, and opened up in the middle, and in the middle there’s some water, and the water is green, and the green is white, and the white comes from up further, comes from the glaciers...]

Celan tells us this landscape is both visible and invisible to Klein. For although Klein “has eyes,” he is separated by “a movable veil” from what is going on in nature, so that everything he sees is “half image and half veil” (halb Bild und halb Schleier). Behind the veil, behind the folded-over surfaces of glaciers, behind the closed eyes of sleepers, lies something Klein cannot see or speak to. Klein feels his separation from the world behind the veil mainly as an incapacity of language:”

Das ist die Sprache, die hier gilt, das Grüne mit dem Weißen drin, eine Sprache, nicht für dich und nicht für mich—denn, frag ich, für wen ist sie denn gedacht, die Erde, nicht für dich, sag ich, ist sie gedacht, und nicht für mich—eine Sprache, je nun, ohne Ich und ohne Du, lauter Er, lauter Es, verstehst du, lauter Sie, und nichts als das.

[That’s the kind of speech that counts here, the green with the white in it, a language not for you and not for me—because I’m asking, who is it meant for then, the earth, it’s not meant for you, I’m saying, and not for me—well then, a language with no I and no Thou, pure He, pure It, you see, pure She and nothing but that.]

Language is at issue because conversation, even amid the brutal snags to conversation that both Klein and Danaë experience, is the event that Celan and Simonides want to stage. Why has Klein come up into the mountains? “Because I had to talk, to myself or to you.” What does Danaë beg of her sleeping child? “That you lend your small ear to what I am saying” (19–20). Neither of them finds their way to a satisfactory conversation but both insist on standing in the gap where it should take place, pointing to the lacunae where it burned. No more than Danaë is Klein able to find “speech that counts here.” He cannot talk the language of glaciers, as she cannot speak to sleep or sea. Yet in the absence of a “language with no I and no Thou,” Klein does manage to exchange some “babble” (Geschwätz) with his kinsman Gross. What kind of language is this?

— Anne Carson, Economy of the Unlost: (Reading Simonides of Keos with Paul Celan)

#m#Paul Celan#Anne Carson#Economy of the Unlost#Economy of the Unlost: (Reading Simonides of Keos with Paul Celan)#Simonides of Keos#nonfiction#Danaë#Lenz#Gespräch im Gebirg

1 note

·

View note

Quote

Occasions of hospitality are as critical to Celan’s biography as they were in the life story of Simonides. To find himself “standing under one wind” with people who turned out to be “strangers” was a recurrent experience that marked Celan’s hopes and entered into his verse.

Anne Carson, Economy of the Unlost: (Reading Simonides of Keos with Paul Celan)

#m#Paul Celan#Anne Carson#Economy of the Unlost#Economy of the Unlost: (Reading Simonides of Keos with Paul Celan)#Simonides of Keos#nonfiction#die schleuse#Martin Heidegger#Martin Buber#alienation#Todtnauberg

1 note

·

View note

Quote

Blank spaces instead of words fill out the verses around you as if to suggest your gradual recession down and away from our grasp. What could your hands teach us if you had not vanished?

Anne Carson, Economy of the Unlost: (Reading Simonides of Keos with Paul Celan)

#m#Paul Celan#Anne Carson#Economy of the Unlost#Economy of the Unlost: (Reading Simonides of Keos with Paul Celan)#nonfiction#Matière de Bretagne

1 note

·

View note

Quote

As Danaë struggles to find a name for something she knows as τὸ δεινόν (“the terrible”), she produces an anguished tautology (“If to you the terrible were terrible …”) in which the two possibilities of babble and God-given speech stand side by side—the latter hauntingly translated into the former, as it must be here among die Geschwätzigen. We have no other words to use. We know they don’t count but we lay them against the abyss anyway because they are what mark it for us, contrafactually. “There may be, in one direction, two kinds of strangeness next to each other,” said Celan once.

Anne Carson, Economy of the Unlost: (Reading Simonides of Keos with Paul Celan)

#m#Paul Celan#Anne Carson#Economy of the Unlost#Economy of the Unlost: (Reading Simonides of Keos with Paul Celan)#Simonides of Keos#nonfiction#strangeness#Gespräch im Gebirg

0 notes

Quote

According to myth, Kastor and Polydeukes are brothers (one mortal, the other immortal) who could not bear to be parted by death and so divide a single eternity between them, spending alternate days on and under the earth, infinitely half-lost. “Now they are living, day and day about,” says Homer. Mortality and immortality continue side by side in them, hinged by a strange arrangement of grace. A poet is also a sort of hinge. Through songs of praise he arranges a continuity between mortal and immortal life for a man like Skopas. And although Skopas believes he is paying Simonides a certain price for a certain quantity of words, in fact he acquires a memory that will prolong him far beyond all these. He will be one of the unlost. Gratitude is in order.

Anne Carson, Economy of the Unlost: (Reading Simonides of Keos with Paul Celan)

#m#Paul Celan#Anne Carson#Economy of the Unlost#Economy of the Unlost: (Reading Simonides of Keos with Paul Celan)#Simonides of Keos#nonfiction#memory#gratitude#Homer

0 notes

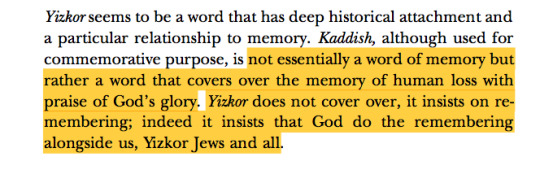

Photo

Anne Carson, Economy of the Unlost: (Reading Simonides of Keos with Paul Celan)

#m#Paul Celan#Anne Carson#Economy of the Unlost#Economy of the Unlost: (Reading Simonides of Keos with Paul Celan)#Simonides of Keos#nonfiction#Yizkor#die schleuse#Kaddish#Sprachgitter#Nelly Sachs#grief#mourning

1 note

·

View note