#Elizabeth Hardwick

Text

"The greatest gift is a passion for reading."

Elizabeth Hardwick

#books#bookish#booklr#bookworm#bookaholic#bibliophile#book blog#book blogger#Features#on books#on reading#read#reader#reading#quote of the week#quotes#quotation#elizabeth hardwick

268 notes

·

View notes

Text

One winter she wore a great lynx coat, and in it she moved, menacing and handsome as a Cossack, pacing about in the trap of her vitality. Quarrelsome dreams sometimes rushed through her speech and accounts of wounds she had inflicted with broken glass. And at the White Rose Bar, a thousand cigarettes punctuated her appearances, which, not only in their brilliance but in the fact of their taking place at all, had about them the aspect of magic. Waiting and waiting: that was what the pursuit of her was. One felt like an old carriage horse standing at the entrance, ready for the cold midnight race through the park. She was always behind a closed door—the fate of those addicted to whatever. And then at last she must come forward, emerge in powders and Vaseline, hair twisted with a curling iron, gloves of satin or silk jersey, flowers—the expensive martyrdom of the “entertainer.”

At that time not many of her records were in print, and she was seldom heard on the radio because her voice did not accord with popular taste then. The appearances in nightclubs were a necessity. It was a burden to be there night after night, although not a burden to sing, once she started, in her own way. She knew she could do it, that she had mastered it all, but why not ask the question: Is this all there is? Her work took on, gradually, a destructive cast, as it so often does with the greatly gifted who are doomed to repeat endlessly their own heights of inspiration.

...Her whole life had taken place in the dark. The spotlight shone down on the black, hushed circle in a café; the moon slowly slid through the clouds. Night—working, smiling, in makeup, in long, silky dresses, singing over and over, again and again. The aim of it all is just to be drifting off to sleep when the first rays of the sun’s brightness begin to threaten the theatrical eyelids.

Elizabeth Hardwick on Billie Holliday (from Sleepless Nights)

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

The greatest gift is a passion for reading. It is cheap, it consoles, it distracts, it excites, it gives you knowledge of the world and experience of a wide kind. It is a moral illumination.

– Elizabeth Hardwick

#fiction#fiction writing#writing advice#writing tips#reading#elizabeth hardwick#quotes#kcawf original#writeblr

322 notes

·

View notes

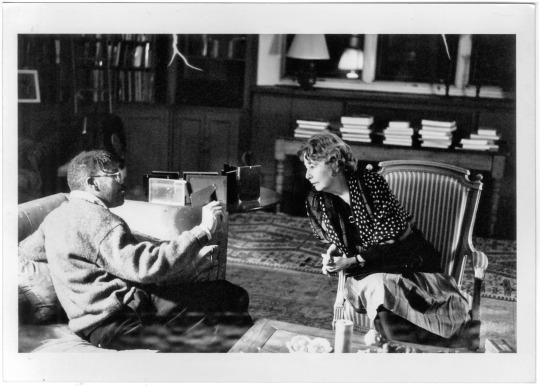

Photo

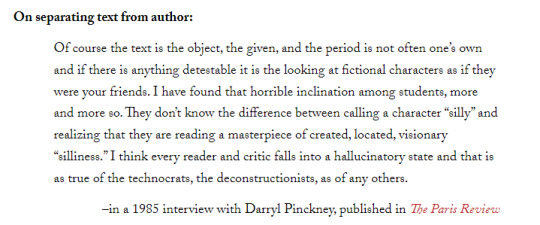

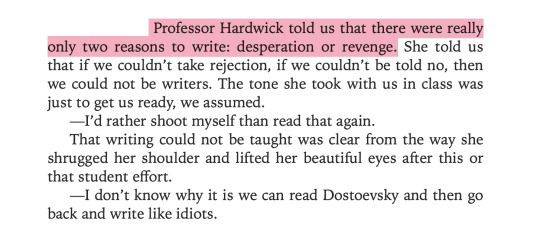

Darryl Pinckney, Come Back in September: A Literary Education on West Sixty-seventh Street, Manhattan (2022)

108 notes

·

View notes

Text

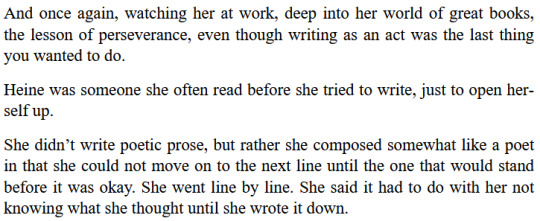

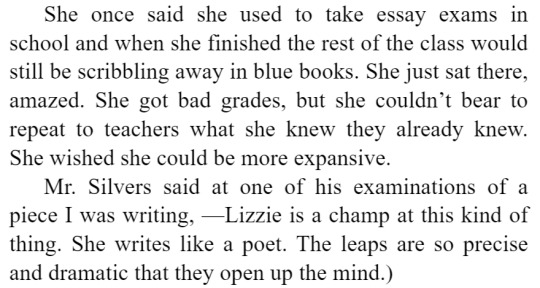

on Elizabeth Hardwick's prose -- poetic or not

Darryl Pinckney, Come Back in September

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Elizabeth Hardwick, July 27, 1916 – December 2, 2007.

With Darryl Pinckney.

10 notes

·

View notes

Quote

I am looking out on a snowstorm. It fell like a great armistice, bringing all simple struggles to an end.

from Sleepless Nights by Elizabeth Hardwick

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

“He rushed into the future with the first glance, swept along by a need for connection that extended the moment before it had begun.”

~ Elizabeth Hardwick, Sleepless Nights

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Elizabeth Hardwick, from “The Art of the Essay” The Uncollected Essays of Elizabeth Hardwick (New York Review of Books, 2022)

#elizabeth hardwick#new york review of books#prose#writing#quotes#the art of the essay#dark academia#academia aesthetic#literature

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fotografías. Susan Sontag, Barbara Epstein, Elizabeth Hardwick y Joan Didion

Fotografías. Susan Sontag, Barbara Epstein, Elizabeth Hardwick y Joan Didion

Fotografías. Susan Sontag, Barbara Epstein, Elizabeth Hardwick y Joan Didion, fotografiadas en 1999 en Nueva York por Todd Eberle.

(A través de Twiteer. Inés Martín Rodrígo)

View On WordPress

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

An amusing flourish in the picture caption to Justin Murphy’s newsletter on Flannery O’Connor: “When was the last time you heard about Elizabeth Hardwick?” The cognoscenti have been hyping a Hardwick revival for half a decade now, to semi-avail. I got in on the game in 2017 by reading her little Herman Melville bio; I wrote about it here. For what it’s worth, I think that’s one of the funnier essays I’ve ever written:

All of the above to say that I approach Hardwick, at this stage of my reading life, with a bit, just a hint really, the proverbial soupçon, whatever that means, of suspicion—with apprehensions of fatigue. These days, for me, somehow, the New York Intellectuals, The New York Review of Each Other’s Books, have lost their luster. If I don’t care about Bloomsbury, why should I care about this even less generally relevant coterie? Their organs have been disintermediated, their politics obsolesced, in the thresher of the 21st century. The problem with ressentiment and separatism, though, is that you miss too much of relevance to yourself, because you have artificially constricted your own soul too far in advance of experience. Lady Ottoline Morrell, Barbara Epstein—sure, if you’re not in the club, who cares? But you would not want to miss a Virginia Woolf, not even in the 21st century: so to Hardwick’s Melville I go.

I suspect Murphy may have had in mind that recent survey that showed the average reader of the New York Review of Books to be, in age terms, pretty much deceased.

I never did read Hardwick’s most celebrated novel Sleepless Nights, with all those blurbs from Sontag, Roth, Didion. I started it right after I read Adler’s Speedboat and it was too similar so I put it down. These aren’t universal writers, Adler and Hardwick, in the way that O’Connor is a universal writer. It’s a different order of being. I may have heard about Hardwick lately—and she’s okay, very intelligent, very civilized; I do think her metropolitan milieu partially liked her so much because she escaped from Hicksville, and I increasingly detest that kind of thing—but nobody would say about her what (if I recall) Robert Fitzgerald said about O’Connor: that she should be mentioned in the company not of Hemingway but of Sophocles. Which might go too far, but is in the ballpark.

youtube

Speaking of mid-to-late-20th-century American letters: over in Tablet, at whose Substack annex I myself sometimes appear, David Mikics nominates Ralph Ellison, Joan Didion, Thomas Pynchon, Flannery O’Connor, and Elizabeth Bishop as the most important postwar American writers and the antidotes to today’s over-politicized rage. No quarreling with the list—I appreciate that he said Bishop where one is probably supposed to say Ashbery—though a little Saul Bellow and a little Don DeLillo wouldn’t be amiss.

If literature can teach anything, it is patience and conviction. We mostly have neither. We lash out violently, apocalyptic and urgent, with our enemies’ lists in hand. The days of rage have returned, both on the right and the left. To weather these tantrums, we should turn back to the writers who oppose the infantile fervor of groupthink—who acknowledge the lostness of the self in the world, the first step to declaring independence.

And speaking of Don DeLillo, I spent the last week and half gratuitously and luxuriously rereading the massive Underworld—truly one of the best books there is—and I wrote about it at length here. Of DeLillo’s oeuvre, I still need to read End Zone and Ratner’s Star, both of which I’ve avoided on principles that have stood me in good stead since grade school: I don’t care about sports and I don’t care about math. And it’s been so long since I read The Names and Mao II that those readings probably don’t count. Underworld, though, is where it’s at, as I write:

For Underworld is, first of all, in the high tradition of the American novel, which, as umpteenth observers from Nathaniel Hawthorne forward have told us, has never been a novel at all, not a sober realist social survey, but a weird symbolic prose-poem, an inward voyage projected out onto the national landscape. Underworld places itself in this tradition with its first sentence: “He speaks in your voice, American, and there’s a shine in his eye that’s halfway hopeful.” The first thing to say about this sentence is that it pays tribute to two sentences from the Great American Novels of the early 1950s, the period when Underworld begins: the first sentence of Bellow’s Adventures of Augie March (“I am an American, Chicago born”) and the last sentence of Ellison’s Invisible Man (“Who knows but that, on the lower frequencies, I speak for you?”). The second thing to say is that, like a line of poetry, the sentence admits of two readings, with “American” as either a noun, which makes the sentence a direct address to the American reader, or an adjective modifying “voice,” declaring a national origin and destiny for the novel’s style. So this is an American romance, and you have to read it like a poem; and, as in Bellow’s and Ellison’s novels, or Faulkner’s and Melville’s before them, the sensibility and suffering that emerges is less the sojourning protagonists’ and more that of the organizing and presiding consciousness. As in a book of poems or in a long poem, it’s the poet you get to know best, and not for nothing does Underworld, in its final one-word sentence, echo no novel at all but the century’s most famous poem, The Waste Land. “Shantih shantih shantih,” Eliot chants in Sanskrit, which DeLillo puts into plain American: “Peace.”

#american literature#flannery o'connor#elizabeth hardwick#don delillo#justin murphy#david mikics#literary criticism

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Elizabeth Hardwick, Sleepless Nights

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Uncollected Essays of Elizabeth Hardwick, edited by Alex Andriesse

The forsythia has already died and blown away in Central Park and the clusters of bloom on the lilac bushes in the suburbs are soon to be a drooping fade. But when you go up to Maine in May the first flowerings are reluctant, not quite ready, not to be hurried. The trees are not yet leafy, not at all. Houses never seen in the summer shadow of tree branches are visible just back from the road even in late spring.

The splendor of the region always retains a pristine frugality in its messages, a puritanical remnant in its pleasures. Like the blossoms, you are reminded that you can wait—and also you can do without. A lonesome pine, country music drift in the air, long-lost sentiments. He’ll never return from the sea (the Merchant Marine) and the blue-eyed girl has gone to the office desks of Connecticut, never to look back. (Puritanical Pleasures, p. 37)

***

The landscape of America seems often like one of those endangered kingdoms in old sagas. Nightly, Grendel steals upon the knights sleeping in the hall and slays the fairest and the weakest alike. The siege, chronic, of change is one that we live with—and so we are never quite sure what has come upon us. Are we in the midst of destruction or renewal? Have we been blessed with something better: or have we, instead, merely a replacement?

The mind cannot hold the memory of the old corner before the supermarket came about, cannot remember the seemingly eternal mortar and brick that stood upon the bare land that is now a parking lot, the space that is waiting, as if under the dominion of a lawsuit in chancery, waiting with its automobiles in rows for some final disposition of the property, some lucky mortgage of partnership. What was once a cotton field has become the pasture for a new appetite, or perhaps the flattened strip of an airplane landing.

Sometimes, dreaming, in the country when it is very quiet, in imagination the Indians return to the northern regions and you meet them, melancholy and still as the woods. But the unconscious is shrinking, and those who thought it triumphant did not see the sudden, unalterable obliteration of the past. We had thought—wrongly—that the past slowly, imperceptibly receded, leaving always its traces clearly visible in the new. (Elections, p. 87)

***

. . . . Surrender to circumstances is for others: amelioration and good luck and grand expectations are for ourselves. (Elections, p. 88)

***

I have never felt free. I do not speak of the constraints of society but of the peculiar developments of my own nature. All my life I have carried about with me the chains of an exaggerated anxiety and tendency to worry, and an overexcited imagination for disasters ahead, problems foreboding, errors whose consequences could stretch to the end of time. I feel some measure of admiration for women who are carefree, even for the careless; but we work with what we are given, and what I know I have learned from books and from worry. (The Ties Women Cannot Shake, and Have, p. 196)

***

Memory: It is a forest. It is the sun and shade, the air current, the luminous crown, the damp root—the precious jungle of our being on earth. In memory, with its density of feeling, the treasures of human experience are preserved, just as the forest represents the aesthetic apotheosis of actual nature. And yet memory is also a menace—dark, lonely, fearful. Our rootings and clingings to memory are a sad entanglement from which one would, at certain times, free himself if he had the power to do so.

In painful memories, those that represent attachments to a lost past, the very suffering distorts the complexity of life, makes the flawed more perfect, the mixed more beautiful than it was, the doubtful more true. Memories are also the mausoleum enshrining resentments and long, futile angers. A need for rest, tranquility, for the promise of the future finally challenges the domination of painful memory. What is hoped is that in giving up the obsession with the past a new present can come into being.

Forgiveness is the goal of troubling memories. If it is possible to set aside the memories, it can then be possible to think of reliving them someday, without desperation, in a new form, kind to our souls, soothing. All the losses of life, whether accidental, inevitable, or simply cruelly thrust upon us, seek to be forgiven. Always what is most important in one's personal life is to forgive the unforgivable.The forest of memory, with its balance of light and shade, of rain and dryness, its terrors and its silences, is not under our complete control. But it accommodates us finally, if the will is there, the wish to forget, the courage to cast off. (When To Cast Out, Give Up, Let Go, pp. 214-15)

***

To speak of a passion for reading is rather self aggrandizing as perhaps it would not have been in the past. This act, except for purposes of the classroom or for information, is self-propelled, unmortgaged, so to speak, not subject to obsolescence or engine trouble or the need for maintenance. It is not often that one is scolded for it, although biographies tell of the wishes of parents to interrupt on behalf of unchopped wood or expensive candles. Perhaps the love of, or the intense need for, reading is psychological, an eccentricity, even something like a neurosis, that is, a pattern of behavior that persists beyond its usefulness, which is controlled by inner forces and which in turn controls. (Reading, p. 230)

***

Proust left a short book titled On Reading. It says, of course, many beautiful things about himself, about decoration (William Morris), Carlyle, Ruskin, the Dutch painters, Racine, Saint-Simon—on and on. And then somewhere in the pages he notes the insufficiency of reading and says that it is an initiation, not to be made into a discipline."Reading is at the threshold of spiritual life; it can introduce us to it; it does not constitute it." (Reading, p. 235)

***

We cannot imagine the shape, the substance of a day in Victorian England, nor the quiet isolation of our own countryside even fifty years ago. Everything good is bought with the blood of someone's lack, someone's wretchedness. And so we are propelled onward, gaining and losing, building and destroying. Some try to hold a little here, save something there, to preserve, to remember; but the preserver is himself shaped out of losses and impatience. All of his little motors of need are running in his flesh just as they are running through the electric current in his house.

"To have time, in the personal sense, is to have an emptiness, an absence, a failure of diversion. Something is withheld from you, and this nothingness gives you time. No amount of money can buy it, and so it is fortunate that few want it. Quite the opposite: Our bodies would not be prepared, our souls and our vanity even less.

It is a jolt, not easy by any means, to find oneself suddenly at the Metropolitan Opera House for Wagner's Parsifal. This splendid, wonderfully successful new production is, like all the others before it since 1882, over four hours long. It is a static, contemplative work; its intensities are inward and abstract. The wound of Amfortas is not an ache, a sickness, a casualty, but the universal unhealed wound of existence. It is healed by the touch of a spear, the instrument of wounds. In a moment of dazzling modern technology, we see a flash of silvery movement—the spear, flung across the stage by Klingsor, is, with the speed of light, shining in Parsifal's hand. For the rest, we look inward, led by the music, into the cave of ourselves.

In this production, and I understand also in Bayreuth, the stage is quite dark throughout. Even the final Good Friday light is only a long, thin stream of whiteness in the shadows. In this way we are at a further remove from the usual involvement with the action on the stage. There is wisdom enough in this, since Parsifal can only be as it is; it is one of those works of art that will not budge to accommodate current taste. There is no way to move it. You must surrender, submit, call upon some sense of motionlessness in yourself. That is, if you want to be there for Redemption.

At Parsifal one must conquer time, or leave, as many do, saying with great unconscious accuracy that they must go home, they haven't time. This loss of time is not an illusion, but a fact for all of us. If, as an amateur, as a civilized person merely, one were to set out to read Shakespeare's works carefully, the Bible, Proust, or Dickens or Gibbon, it would be necessary to undergo some rare kind of discipline of withdrawal, to set up conditions very special, to work against the grain of our lives. Where will the time be found?

Wagner began Parsifal in 1877 and finished it in 1882, one year before his death. Nietzsche was distressed by its Christian feeling, but wrote: "It is as if someone were speaking to me again after many years about problems that disturb me..." This is still true. There in the long, pure hours we think not only of the Grail and the Sword but of ourselves and the others around us, people from space, living in a new continuum. (Parsifal in its entirety, pp. 255-56)

***

We aim to frighten in our prophecies, to predict loss, diminishment. Going away from rightness, falling off, aridity, future violence: it is not the purpose of modern art to tell good news, that is, if it is concerned at all with society's future. Mary, robes flying, was lifted up to Heaven, and she smiled with joy. We would flee from the Brave New World, that is, if we could. Prediction clings even to the most banal, for banality is itself a great insistence, always there asking for its share or more than its share. Our carelessness will bear its new careless fruit, our emptiness will grow and grow. These acts of recognition please in all the arts. Ugliness and sadness reach out to us. (Notes on Leonardo and the Future of the Past, p. 272)

1 note

·

View note

Photo

“Educate, Entertain, Scold, Charm”: Merve Emre, interviewed by Lauren Kane, for the New York Review of Books

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

searched for podcast episodes on Elizabeth Hardwick because I can’t stop learning about her and am not ready to give up on book podcasts even though I almost never like them. the two hosts of this podcast called Book Fights have accused her of “tapdancing in the spotlight” in her essay on MLK’s funeral — they suggest that her prose is too showy and flowery, and given the gravity of the subject matter she should have “gotten out of the way with [her] own bullshit” … I haven’t read the essay but this take really doesn’t cohere with what I know of her motives nor my experience of her writing. so now I have to read it for myself. will try to keep an open mind about the piece but these men seem like assholes with reading comprehension problems — frankly surprised that they edit a literary magazine

7 notes

·

View notes