#Eugene Lloyd

Text

gent boys my beloved 🥰 this is nearlyyyy all of them, the others will be drawn....eventually

#victors art#steve mcgregor#bill chambers#alan gray#eugene lloyd#scott tlo#thomas connor#bendy and the dark revival#bendy and the ink machine#bendy the lost ones#batim#batdr#batim tlo#q#im missing three#one day ill design the two that dont have designs

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

having nightmares about murdering your friends every night? join their punk ass band and see what happens! safe to say lloyd's going through it !!!

(some band au arts plus some doodles :]. the drums from the first drawing under cut, i REFUSE to not show them in this post i worked WAYYY too hard)

#ninjago#twigs art#■ band au ■#blood#death#lloyd garmadon#ninjago lloyd#lloyd montgomery garmadon#lego ninjago#brad tudabone#tw death#tw blood#tw body horror#body horror#ninjago au#ninjago sally#sally mander#ninjago gene#eugene ius#scrapbookshipping#thats gene x sally for u. if u even . care#darkleys kids#ninjago darkleys#unfortunately not adding greenflower tag cause it aint really greenflower

282 notes

·

View notes

Text

heeyy about time i do something like this HAHA

we have a server! the darkleys server! it's mostly a place to just chill and chat! i've also noticed that a lot of people want a place where other greenflower fans can talk and hang out ヽ(*・ω・)ノ

here's the invite! make sure to read the rules and react to the last message to get access! (if it doesn't work, pm me here and i can make a new invite link)

https://discord.gg/mB9VBa6B3N

@twigs-sprigs rendered the art above and is also modding the server!!! <3 my lines are under the cut if you want to see em!

anyway! happy greenflowering! :D

#ninjago#lloyd garmadon#brad tudabone#sally mander#eugene ius#ninjago lloyd#ninjago brad#ninjago sally#ninjago gene#forgivenshipping#greenflowershipping#forgivenship#darkleys kids#ninjago darkleys kids#evan's art!

304 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nimona

Movies watched in 2023

Nimona (2023, USA)

Directors: Nick Bruno & Troy Quane

Writers: Robert L. Baird & Lloyd Taylor (based on the graphic novel by ND Stevenson)

Mini-review:

This was so f**king good. What a groundbreaking, creative, original and incredibly fun movie. It's honestly mindblowing how much world building and character development the film manages to pack in just 90 minutes. And gosh, Nimona and Bal are (anti)heroes for the ages, there's no doubt about that. As for the animation, I have to say I've never seen a movie that looks quite like this. I love that most animation studios have begun to push their boundaries after the release of Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse, cause thanks to that we're getting absolutely stunning movies. Also, on top of the amazing animation and characters, the movie delivers a powerful message that feels painfully timely in this day and age. Seriously, I will never stop thanking Annapurna and Netflix for saving this from oblivion when Disney decided to cancel the project (most likely over its wonderful gay content). I really hope Nimona reaches the audience that needs it the most, and I'm so so so glad it finally made it to our screens, cause it's definitely worth the wait.

#nimona#nimona netflix#nimona movie#ballister boldheart#ambrosius goldenloin#chloe grace moretz#chloe moretz#riz ahmed#eugene lee yang#frances conroy#lorrain toussaint#beck bennett#rupaul#sarah sherman#indya moore#julio torres#nick bruno#troy quane#robert l baird#lloyd taylor#nd stevenson#animation#netflix#3d animation#lgbt+#lgbtq#queer movies#gay#gay characters#movies watched in 2023

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Nimona (2023)

My rating: 8/10

That bit with the statue, I mean. Dude.

#Nimona#Nick Bruno#Troy Quane#Robert L. Baird#Lloyd Taylor#Pamela Ribon#Chloë Grace Moretz#Riz Ahmed#Eugene Lee Yang#Youtube

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

#das boot#das boot 2018#klaus hoffmann#karl tennstedt#robert ehrenberg#cassandra lloyd#ulrich wrangel#benno schiller#johannes von reinhartz#frank strasser#eugen strelitz#julius fischer#polls#das boot polls#let's start with the easy one#own post

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

29.07.2023

#Mira-Marathon

Cartoon

Name: Nimona (2023);

Production studios: Annapurna Pictures, Annapurna Animation;

Director by: Nick Bruno, Troy Quane;

Screenwriters: Marc Haimes, Pamela Ribon, Lloyd Taylor, Keith Bunin, Troy Quane, Robert L. Baird;

Starring: Chloë Grace Moretz, Riz Ahmed, Eugene Lee Yang, Frances Conroy, Lorraine Toussaint;

Genres: Science Fiction, Action, Adventure;

Running Time: 1 hours 39 minutes;

"Nimona" is a cartoon that tells the story of Knight Ballister, the main suspect in the murder of the Queen, who meets Nimona, a dangerous and mysterious creature. It's an exciting adventure story with well-written characters and beautiful animation.

My rating: 9/10

#mira marathon#cartoon#nimona#2023#annapurna pictures#annapurna animation#nick bruno#troy quane#marc haimes#pamela ribon#lloyd taylor#keith bunin#robert l baird#chloë grace moretz#riz ahmed#eugene lee yang#frances conroy#lorraine toussaint#science fiction#action#adventure#1 hour#9/10

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Was supposed to watch Indy Jones 5 at the Lunar Drive-in (that is closing next week) with but COVID..... so watched this instead. it's GREAT. Adapted from a Graphic Novel by ND Stevenson (SPOP), with Screenplay by Robert Baird (Big hero 6) and Lloyd Taylor.

Chloe Grace Morez as Nimona, Riz Ahmed as Ballister and .... TRY GUYS Eugene as Ambrosius? I was not expecting that. nice.

#nimona#nd stevenson#robert baird#lloyd taylor#chloe graze moretz#riz ahmed#eugene lee yang#qd#Youtube

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

6 giugno … ricordiamo …

6 giugno … ricordiamo …

#semprevivineiricordi #nomidaricordare #personaggiimportanti #perfettamentechic

2015: Pierre Brice, nato Pierre-Louis Baron Le Bris, attore francese famoso in Germania. (n. 1929)

2013: Esther Williams, Esther Jane Williams, è stata una nuotatrice e attrice statunitense. (n. 1921)

2008: Gene Persson, Eugene Clair Persson, è stato un attore, produttore teatrale e cinematografico statunitense. Ha sposato Shirley Knight e dopo il divorzio sposò Ruby Persson. (n. 1934)

2005:…

View On WordPress

#6 giugno#6 giugno morti#Anne Bancroft#Anne Marno#Blanch Jurka#Blanche Yurka#Dana Elcar#Domenico Maggio#Elvio Calderoni#Enrichetta Thea Prandi#Esther Jane Williams#Esther Williams#Eugene Clair Persson#Gene Persson#Gualtiero De Angelis#Jack Haley#Larry Blyden#Larry Riley#Lloyd Hughes#Magda Gabor#Magdolna Gabor#Massimo Osti#Mimì Maggio#Mort Hall#Mort Mills#Pierre Brice#Pierre-Louis Baron Le Bris#Ricordiamo#Ruggero De Daninos#Thea Prandi

1 note

·

View note

Text

Deadline’s Read the Screenplay series spotlighting the year’s most talked-about scripts continues with Nimona, Netflix‘s animated feature based on ND Stevenson’s 2015 National Book Award-nominated graphic novel about finding friendship in the most surprising situations and accepting yourself and others for who they are.

Nick Bruno and Troy Quane (co-directors of Spies In Disguise) directed the film, which was adapted by Big Hero 6 scribe Robert L. Baird and Spies co-writer Lloyd Taylor and features the voices of Riz Ahmed and Chloë Grace Moretz in the lead roles. Frances Conroy, Lorraine Toussaint, RuPaul Charles, Eugene Lee Yang, Indya Moore, Sarah Sherman and Beck Bennett also have voice roles.

A family-focused film with authentic queer themes set in a vibrant techno-medieval world (credit to teams at Blue Sky Studios and DNEG Animation), the plot centers on Ballister Boldheart (Ahmed), a knight in a futuristic medieval world, who is framed for a crime he didn’t commit. The only one who can help him prove his innocence is Nimona (Moretz), a mischievous teen with a taste for mayhem — who also happens to be a shapeshifting creature Ballister has been trained to destroy.

Baird and Taylor said their main challenge in the adaptation was to stay true to Stevenson’s story while morphing it from the episodic form of the novel to a feature-length narrative – in itself a process of shapeshifting that mirrors one of the novel’s core themes.

Nimona, which was just nominated for Best Animated Film at the Critics Choice Awards, had a long path to travel to get to its world premiere at the Annecy Animation Festival in June, followed by a theatrical run ahead of its release on Netflix on June 30.

Then-20th Century Fox’s Blue Sky originally optioned Stevenson’s novel the year it was published, and the project moved forward despite the Disney-Fox merger and then the pandemic. But it almost didn’t survive a third blow: Disney shuttered Blue Sky in April 2021, halting Nimona mid-production.

Blue Sky principals Baird and Andrew Millstein kept pushing on the the project however and eventually found a partner in Annapurna’s Megan Ellison, who sparked to its themes. Baird and Millstein became EPs and created Shapeshifter Films to complete the movie, which then landed at Netflix. The pair have since joined Ellison at her company, forming Annapurna Animation.

Click here to read the script.

219 notes

·

View notes

Text

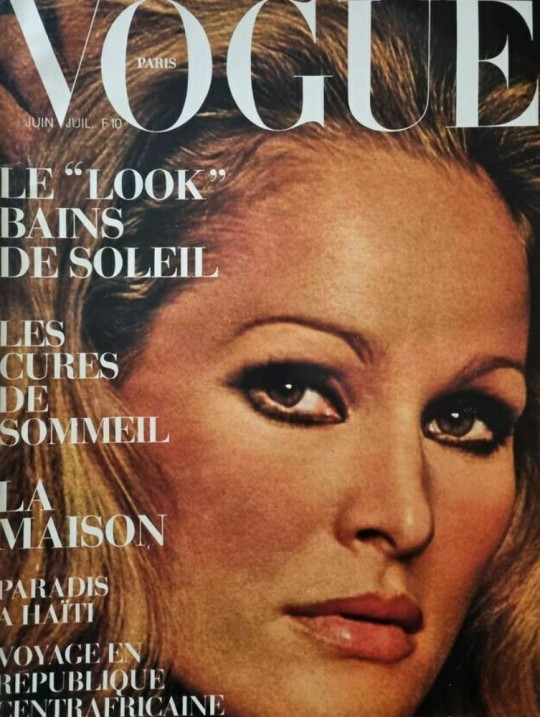

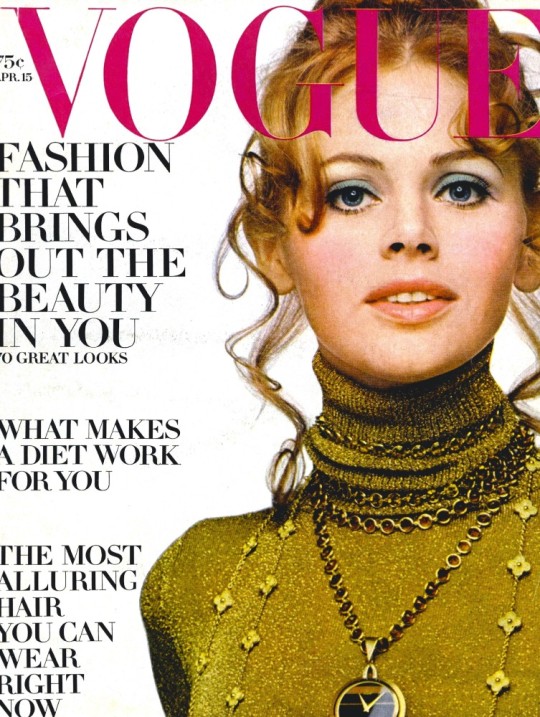

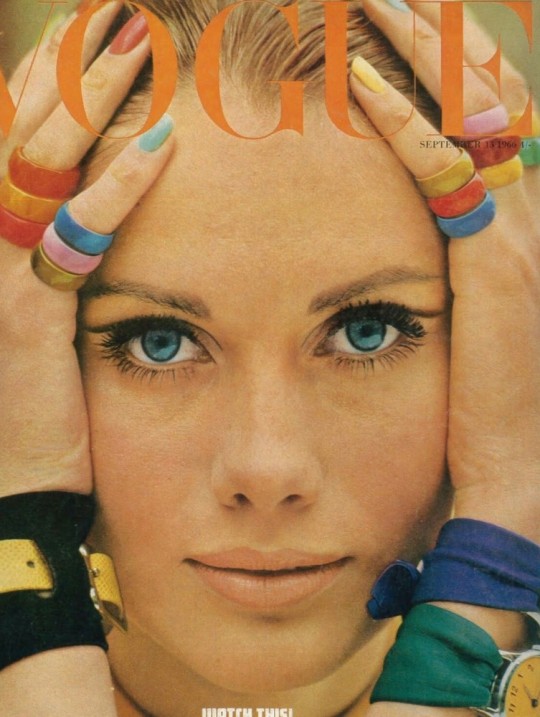

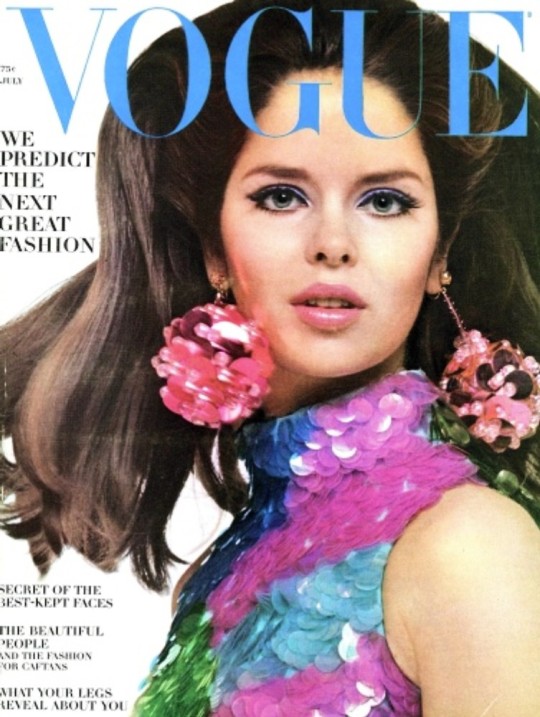

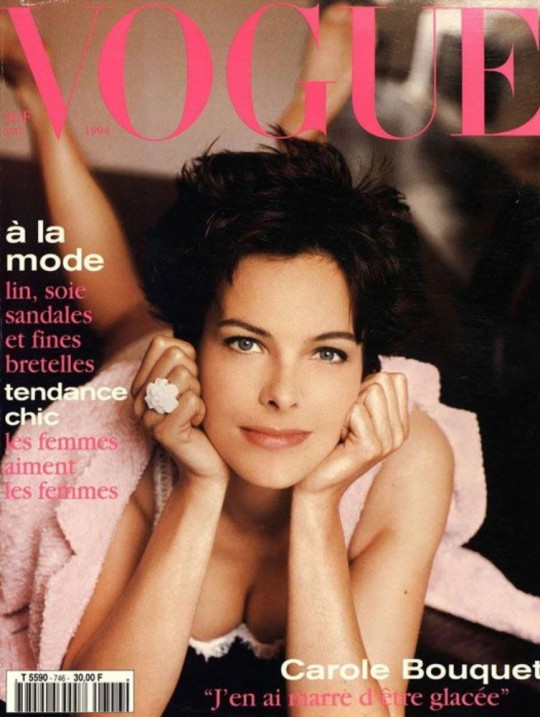

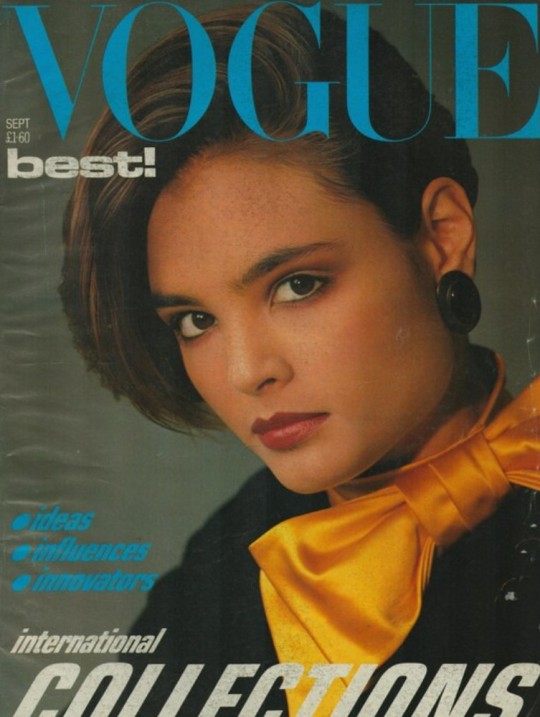

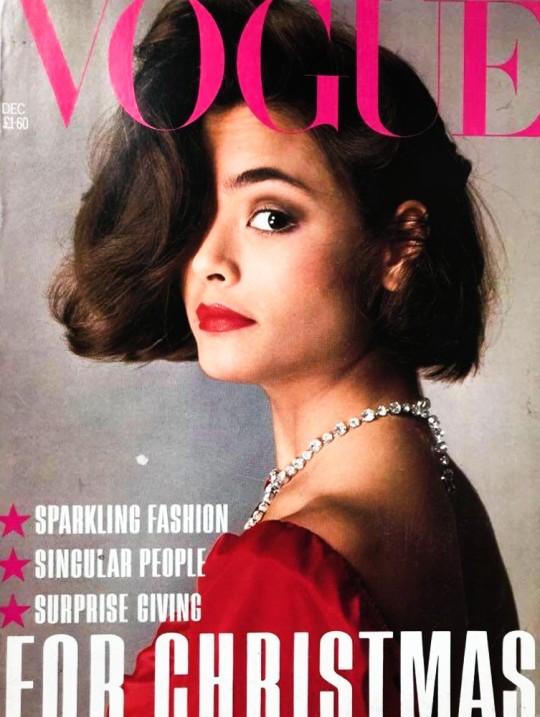

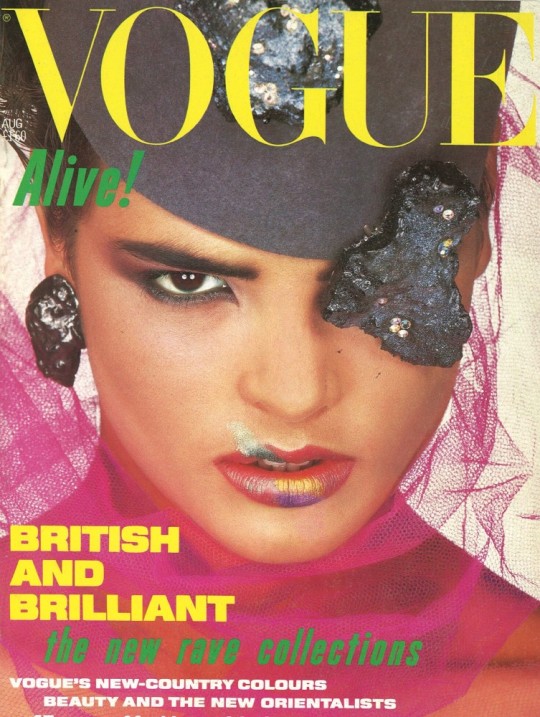

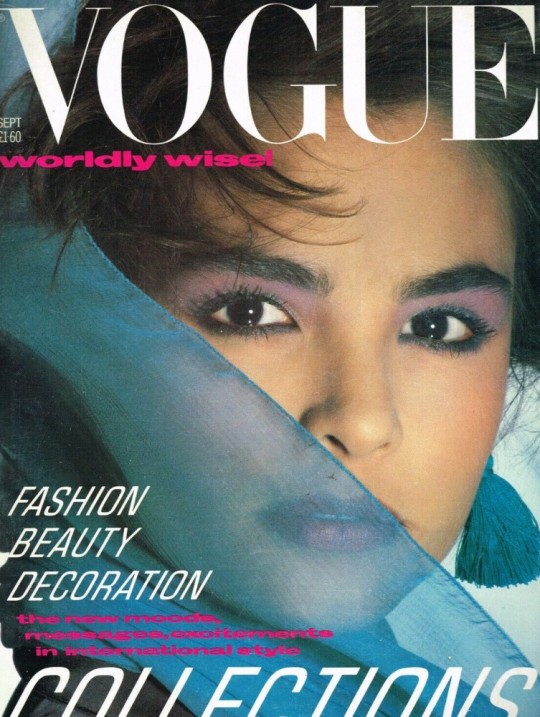

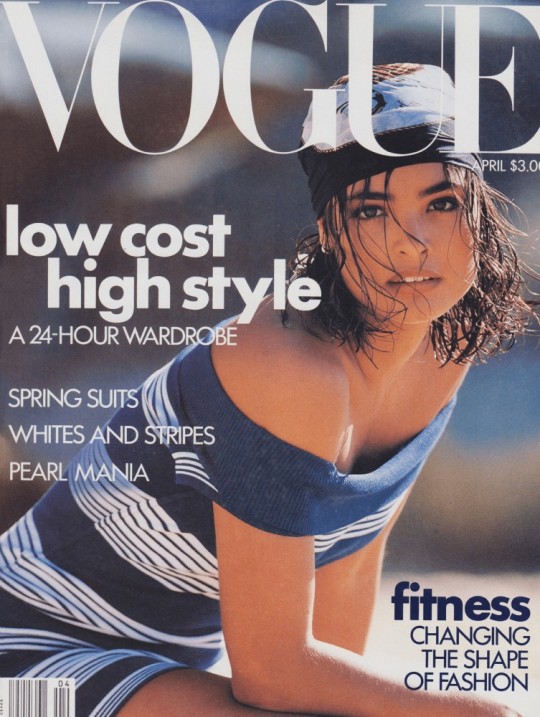

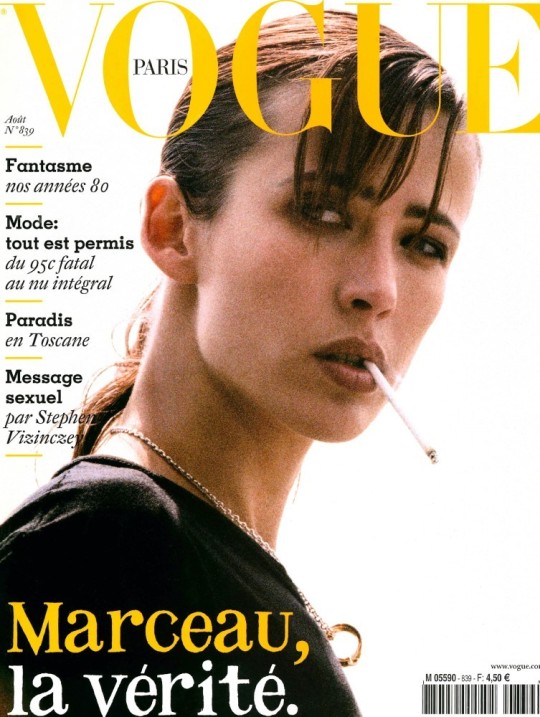

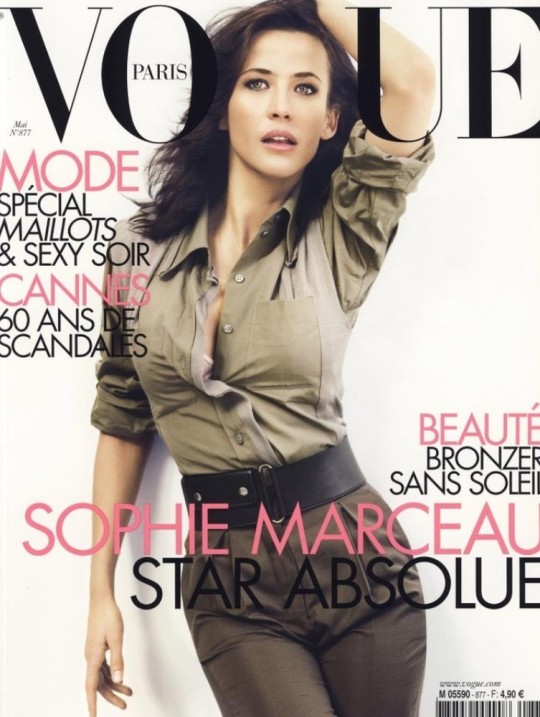

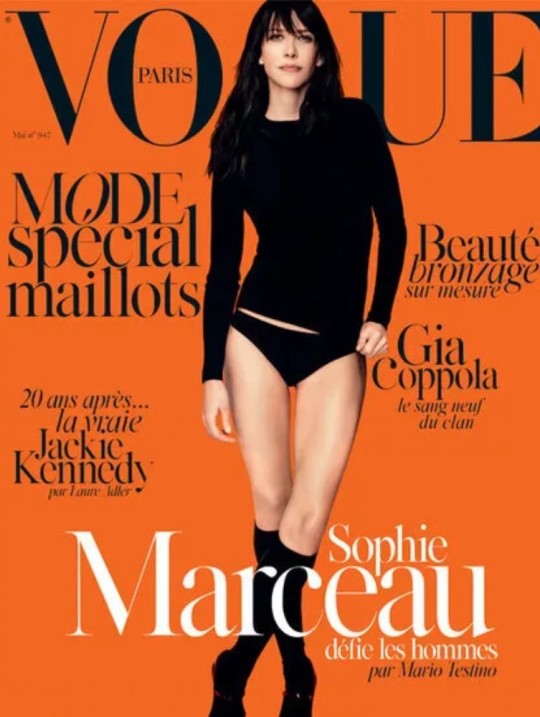

Bond Girls on Vogue (Part 1)

Ursula Andress

British Vogue, April 15, 1966, by Duffy

Vogue Paris, June/July 1972, by Rene Chateau

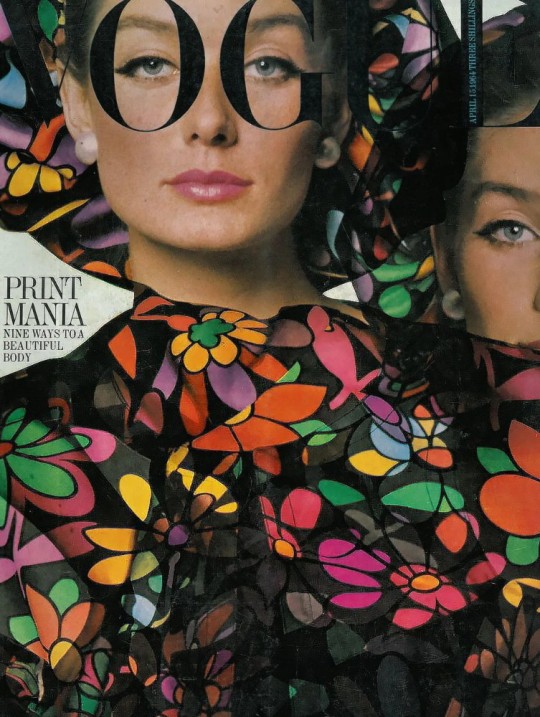

Tania Mallet

British Vogue, July 1961, by Eugene Vernier

British Vogue, July 1962, by Henry Clarke

British Vogue, October 1, 1963, by Duffy

British Vogue, April 15, 1964, by David Bailey

Claudine Auger

Vogue Paris, November 1971, by Henry Clarke

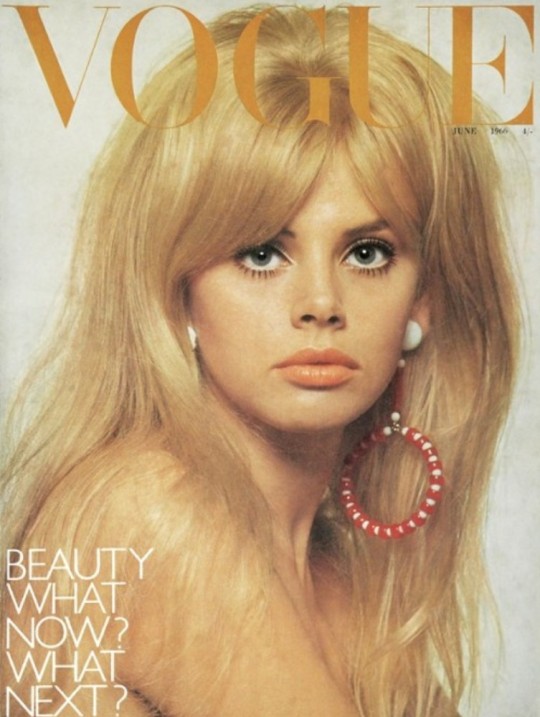

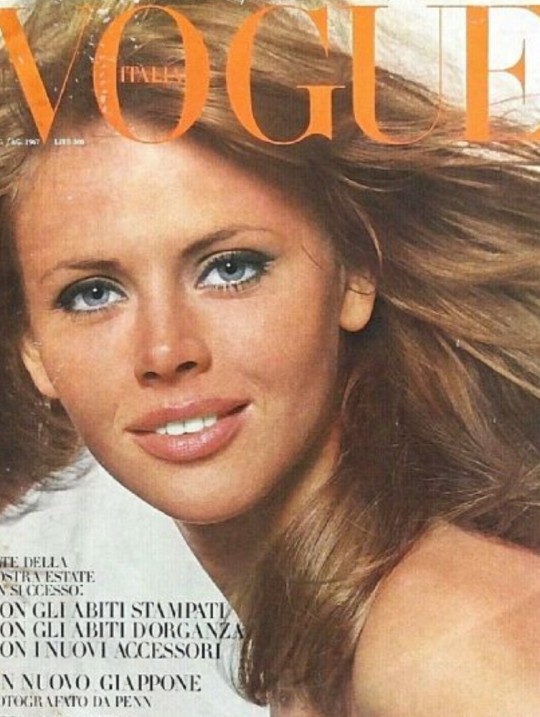

Britt Ekland

British Vogue, June 1966, by David Bailey

Vogue Italy, July 1967, by David Bailey

American Vogue, April 15, 1969, by Gianni Penati

British Vogue, September 1969, by Barry Lategan

Maude Adams

British Vogue, September 15, 1966, by Saul Leiter

Barbara Bach

American Vogue, July 1966, by Richard Avedon

Carole Bouquet

Vogue Paris, May 1994, by Dominique Issermann

Talisa Soto

British Vogue, September 1983, by Patrick Demarchelier

British Vogue, December 1983, by Albert Watson

Vogue Germany, December 1983, by Albert Watson

Vogue Italy, May 1984, by Hiro

British Vogue, August 1984, by Albert Watson

British Vogue, September 1984, by Paul Lange

British Vogue, February 1986, by Lord Snowdon

American Vogue, April 1989, by Patrick Demarchelier

Vogue Spain, May 1988, by Eric Boman

Famke Janssen

Vogue Italy, March 1987, by Hiro

Michelle Yeoh

Vogue China, October 2022, by Agnes Lloyd-Platt

Vogue Taiwan, November 2022, by Agnes Lloyd-Platt

Sophie Marceau

Vogue Paris, August 2003, by Inez & Vinoodh

Vogue Paris, May 2007, by Mario Testino

Vogue Paris, May 2014, by Mario Testino

Vogue France, April 2024, by Quentin de Briey

#bond girls#on the cover#vogue#ursula andress#tania mallet#claudine auger#britt ekland#maude adams#barbara bach#carole bouquet#talisa soto#famke janssen#michelle yeoh#sophie marceau#british vogue#vogue uk#vogue paris#vogue italia#italian vogue#vogue italy#american vogue#vogue us#vogue deutsch#vogue germany#vogue españa#vogue spain#vogue china#vogue taiwan#vogue france#fashion photography

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

An essay I wrote for school on Strange New Worlds' problems with ableism, complete with bibliography:

Star Trek: Strange New Worlds has numerous problems, from its retooling of the Gorn into knockoff xenomorphs to its erasure of Spock’s Jewish roots to its overreliance on nostalgia, but its most glaring flaw is its painful undercurrent of ableism. The conflation of disability with death, the ignorance and tacit pardoning of eugenics, and the disposal of multiple disabled characters come together to weave a harmful and ignorant pattern in the show’s writing.

Christopher Pike’s character in Strange New Worlds is defined by disability. The dilemma he wrestles with in almost every episode is the looming specter of his future disability, which was revealed to him via time crystal in season two of Star Trek: Discovery. In the twelfth episode of season two, “Through The Valley of Shadows”, Pike must harvest a time crystal in order to send the life’s story of a dead alien to the future to protect it from an evil artificial intelligence intent on destroying all life in the galaxy. When Pike touches the crystal, he sees visions of his future, in which he is caught in a deadly radioactive explosion and left with severe burns and full body paralysis, able to move and communicate only through a specialized wheelchair. “The sequence ends with a final linked pair of nightmarish shots, a centred close-up of the older Pike’s face beginning to melt as he screams matched with the younger Pike’s own horrified scream as he falls backward into the present moment,” (Muredda, Angelo). As Muredda says later in the same article, this portrayal imagines disability as “a terminal point, something to scream about in terror, and the embodied sign of no liveable future at all.” The depiction of disability as a horrifying fate, and of the disabled body as an object of disgust and/or fear has a long history in the genres of horror and science fiction; previous and current Star Trek series are not immune to this. The Borg Queen, who appeared most recently in Picard, is missing most of her lower body and uses a robotic replacement to walk— her prosthetic spine is used as an object of horror and disgust when she first appears in First Contact (1996).

While Strange New Worlds had the opportunity to break this pattern and defy ableist stereotypes with Pike, they chose instead to follow the path Discovery had laid for them. Despite the fact that it is made very clear that Pike will be disabled, not killed, by the explosion he will be caught in in the future, every character within the narrative speaks of Pike’s fate as if he is going to die. Pike says, less than twenty minutes into the pilot: “I know how and when my life will end.” This writing decision mirrors the real-life belief that disabled peoples’ lives are akin to “a fate worse than death” or “not worth living,” a sentiment which has led to real deaths: “. . . [early in the pandemic] this belief — that we’re just surviving, not living, and thus have limited quality of life — lead to forced DNRs being put in the files of disabled people in the UK and lead directly to the death of a disabled man, Michael Hickson,” (Lloyd, Kelas). Hickson was denied treatment for pneumonia in Austin, Texas due to his doctor’s perception that he “didn’t have much of a quality of life.” He was put in hospice against his family’s wishes and died at the age of 46. (Shapiro, Joseph). For Strange New Worlds to equate Pike’s disability to the end of his life is irresponsible and reinforces the cultural biases that led to the death of Hickson and continue to impact the quality of treatment disabled people receive the world over.

Christopher Pike’s initial appearance in the original series episode “The Menagerie” was actually very progressive for the time; despite the limited communication of the blinking-light system in his wheelchair and his ending being living out the last of his life in a virtual reality where he could walk again, he was still a disabled person on television in a position of power.

When Pike first appeared, the Ugly Laws were still in place in much of the United States. Someone visibly disfigured/disabled was not to be seen in public spaces, at the risk of fines or jail . . . Captain Pike’s appearance in The Original Series was revolutionary. Here was not just a visibly disabled person, but they were someone Spock respected and cared about enough to risk his career for. [Disabled people] didn’t have a great existence, but they had one, and Pike was still valued as a person. (Lloyd, Kelas).

It would have been quite easy for the writers to modernize Pike’s portrayal to further disability representation in the way Pike first did: @hard-times-paramore has written an alternate ending (a mixed media series titled “The Captain’s Chair”) for Strange New Worlds in which Pike goes on to captain a new starship after becoming disabled, assisted by an interpreter, a caretaker, and futuristic medical technology. This alternate ending carries the message that disabled people are still people, who can and should be allowed a place in science fiction, as opposed to the current message sent by SNW, which is that significant disability is akin to a death sentence, even in a fantastical future.

However, there is more to Strange New Worlds’ portrayal of disability than just Captain Pike. The show is also very preoccupied with genetic augmentation and the Federation’s attitude toward it. While this is far from unique among Star Trek media, unlike other Trek properties which have covered this topic (Doctor Bashir, I Presume?, Chrysalis, Space Seed, Affliction/Divergence, etc) Strange New Worlds does not acknowledge the real-life equivalent to science fiction genetic augmentation: eugenics. SNW portrays genetic augmentation as a neutral practice targeted unjustly by the Federation because of outdated prejudices, with no examination of what genetic augmentation is a stand-in for. While the original series (in “Space Seed”) first introduced the Federation’s ban on genetic augmentation as a justified protective measure against the breeding of warlike “superior ambition” among men of “superior ability,” Strange New Worlds portrays genetic augmentation as an unjustly discriminated-against trait whose origin and consequences mean little to nothing.

Strange New Worlds’ main conduit for their genetic augmentation plotlines is Una Chin-Riley, the first officer of the Enterprise. She is a member of an alien species called Illyrians, who genetically modify themselves to suit the environments of planets they colonize. She herself was genetically modified as a baby, and is thus legally barred from joining Starfleet— however, she lied on her application to Starfleet Academy to get in. The plots revolving around her concern her arrest for violating Federation law and the subsequent trial, which is used as an extended metaphor for discrimination against, and the fight for civil rights for, marginalized groups. “Ad Astra Per Aspera,” the episode covering Una’s trial, is intentionally vague with its metaphor, to the point that just about any marginalized group could be represented by it. This episode is, on its face, fine. It argues against discrimination through allegory quite adeptly, discussing the concept of “passing” as part of a non-oppressed group and broaching the topic of systemic oppression. However, it has one glaring flaw in its base: the stand-in it chose for real-life oppression. Genetic modification, unlike other fantastical attributes that can be used to metaphorize oppression, has a bloody real-life history involving the deaths and sterilizations of millions of people. Strange New Worlds, however, appears ignorant of this fact: not once does the topic of eugenics come up in any of their episodes about genetic augmentation. Not once does the topic of disability come up, either. This is either an unwillingness to engage with the realities of what those who seek to change humanity’s genes have done and continue to do, a grave oversight, or mere ignorance. Whichever one it is, this omission of eugenics from the narrative of genetic augmentation is one that cannot be ignored. Its omission reads as a tacit endorsement of genetic augmentation at times, such as when Una and La’An say, in “Ghosts of Illyria”:

LA’AN: All my life I've hated augments. Hated what people thought of me because I was related to them. Understanding why they were outlawed in the Federation. The damage they did. They almost destroyed Earth.

UNA: [. . .] My people were never motivated by domination. Illyrians seek collaboration with nature. By bioengineering our bodies, we adapt to naturally-existing habitats. Instead of terraforming planets, we modify ourselves. And there's nothing wrong with that.

By ignoring the part eugenics plays in Star Trek’s portrayal of augmentation, and instead portraying the issue as a matter of prejudice based off of the fictional event of the Eugenics Wars— when augmented “supermen” became dictators and killed millions in conquest and war— Strange New Worlds completely fails to examine the real-life implications of their metaphor.

What makes this episode’s flaws worse is that another Star Trek series already portrayed the potential expulsion of a genetically augmented person from Starfleet, handling it with better understanding of the eugenic undertones of genetic augmentation, and it did so in 1997. In the season five episode of Deep Space Nine, “Doctor Bashir, I Presume?”, it is revealed that Julian Bashir, chief medical officer of Deep Space Nine, was illegally genetically modified by his parents as a small child and is in danger of being thrown out of Starfleet because of this revelation. Throughout the course of the episode, the audience learns that Bashir’s parents chose to modify him because he was intellectually disabled as a child. His mother believed that his life would be better if he were “normal,” while his father wanted a successful son and believed that intellectual disability was inimical to that end. The episode expresses, through Julian’s anger at his parents, that modifying a person to rid them of perceived “undesirable traits” is wrong, but that it is also wrong to unilaterally bar people from Starfleet based on a decision that was made for them by eugenicist parents. This message is far more clear than “Ad Astra Per Aspera”’s, especially on the subject of disability and eugenics. Strange New Worlds’ complete neutrality on and/or tacit approval of genetic augmentation/eugenics, in contrast to Deep Space Nine’s nuanced examination of the topic, is glaring.

The specific problem with Strange New Worlds’ neutrality on genetic modification is that for a species to be changed on a genetic level for any reason, traits must be eliminated. In a science fiction setting, this can be accomplished by simply changing the genetic structure of a consenting adult with a futuristic medical tool, rather than through violence as in our reality, but this, too, presents ethical problems. What is considered a problem to be cured? Who makes that decision? What happens to those who don’t want something modified out of them? What happens to any children they may have? Who gets to have control over technology with the power to eliminate or introduce genetic traits at will? What place do disabled people have in a society built off of achieving peak physical performance in a given environment? Strange New Worlds attempts to answer none of these questions. It acknowledges none of them. And this silence leaves disabled people out of the conversation completely by not even considering them. Today, in Denmark and Iceland, almost 100% of fetuses with Down Syndrome are aborted; the law in Iceland even specifically states that abortion is permitted after 16 weeks only if the fetus has a “deformity,” which Down Syndrome is specified to count as. (Quinones, Julian; Lajka, Arijeta). An entire anti-vaccine movement was begun in Britain because parents were so afraid of having a child with autism and chronic digestive disease, a child like me, that they risked their children dying of measles. This is what real-life genetic engineering looks like, and Strange New Worlds has failed to acknowledge that. I, at least, consider that a failure of writing, empathy, and allyship.

Strange New Worlds’ portrayal of disability is not relegated to Pike’s fate and Una’s augmentation, however. The show has several other characters who either are disabled or become disabled at one point. Rukiya, Dr. M’Benga’s daughter, is treated less as a character and more as an object for the emotional development of her father, a position many young disabled girls occupy in fiction. “[This story] centers Dr. M’Benga, and his pain, and his struggle, and doesn’t grapple with what Rukiya’s going through.” (Lloyd, Kelas). Rukiya has an untreatable terminal cancer, and is kept in a state of suspension in the transporter buffer by her father while he searches for a cure. Her story ends when the Enterprise enters a sentient telepathic nebula with the power to warp reality, and it offers to keep Rukiya within itself so that her disease will not progress and she will be able to grow up. M’Benga decides that this is the best option, and so relinquishes Rukiya to the nebula. She is never seen again. “She is disabled, and then she’s removed . . . The disabled person was put into [a] box and left behind, like so many disabled people have been put away in care homes and institutions and left behind.” (Lloyd, Kelas). Jax agreed, saying: “It just felt like she was poofed away for convenience. Like, ‘There! The problem is gone! The terminal illness or the girl? Both! Don’t worry about it!’”

The only other disabled main character on SNW is Hemmer, who is a member of a blind species called the Aenar. “While the Aenar cannot see, they believe that their telepathy gives them a ‘superior’ awareness of their surroundings compared to sighted people (Vrvilo, 2022). Because of this, the Aenar are highly criticized by the disability community as falling into the ‘magically disabled’ trope.” (Harris, Heather Rose). Bruce Horak, the actor who plays Hemmer, is blind himself, which is a genuinely good decision in terms of representation and support for the disabled community. However, Hemmer dies in the penultimate episode of season one. This decision was not received well by disabled fans: “It just kind of felt like a kick in the teeth. I finally found some good disability representation played by a disabled actor [who] isn’t a one off character, and they die in the first season.” (Jax). Both Hemmer and Rukiya are left behind by the narrative of Strange New Worlds, and with them, so too are disabled perspectives. The crew of the Enterprise is now entirely able-bodied, and the only remaining character whose story directly concerns disability is Pike, who repeatedly asserts that his life will end once he becomes disabled. This state of affairs is the embodiment of being spoken for, and being spoken over.

There is a saying in the disabled community: “Nothing about us without us.” This saying means that abled people should not attempt to help, treat, or speak about disabled people without involving disabled people in their efforts. Disabled people are often denied autonomy over their bodies, medical care, relationships, and lives; to deny them a part in operations meant to help them is to further deny them dignity and respect. This is what Strange New Worlds is doing by writing disabled stories with no disabled writers in the room— while they did well by casting Bruce Horak to play Hemmer, it is not enough to have disabled people in front of the camera. They must also play a part in writing, directing, planning, and all other work behind the scenes if Strange New Worlds wishes to tell their stories. In order for Strange New Worlds to rectify their pattern of ableism, they must listen to disabled voices.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

#star trek#star trek: strange new worlds#star trek snw#snw#strange new worlds#ableism#media analysis#disability#snw critical#this one is my tag

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

what if darkleys kids but...transformers................

yeah.....they be transformin...silly new au

#ninjago#twigs art#lego ninjago#lloyd montgomery garmadon#brad tudabone#sally mander#eugene ius#lloyd garmadon#ninjago lloyd#ninjago brad#ninjago sally#ninjago gene#ninjago darkleys kids#darkleys kids#ninjago darkleys#even though this is a greenflower au idk if i should tag it#eh its alright we'll leave it at that#transformers#transformers fanart#do these count as transformers ocs???#they basically are#transformers oc

496 notes

·

View notes

Text

im back on my bullshit you guys

woo! pride!

#ninjago#lloyd garmadon#ninjago lloyd#brad tudabone#ninjago brad#eugene ius#ninjago gene#ninjago sally#darkleys#ninjago darkleys kids#darkleys kids#evan animates!#evan's art!

545 notes

·

View notes

Text

NIMONA(2023)

a netflix original movie based off the graphic novel by ND Stevenson(2015) about a knight framed for a crime he did not commit, and the only person who can help him prove his innocence is Nimona, a shape-shifting teen who might also be a monster he’s sworn to kill.

starring: Chloë Grace Moretz, Riz Ahmed, Eugene Lee Yang, Frances Conroy, Lorraine Toussaint, Beck Bennett, Indya Moore, RuPaul Charles, Julio Torres, & Sarah Sherman

maturity rating: PG13 (violence & action, thematic elements, some language, & rude humor

directors: Troy Quane & Nick Bruno

producers: Karen Ryan, Roy Lee, & Julie Zackary

writers/screenplay: Robert L. Baird, Lloyd Taylor

#not my stuff#nimona#icons#nimona movie#nimona 2023#netflix original#chloë grace moretz#riz ahmed#eugene lee yang#frances conroy#loraine toussaint#beck bennett#indya moore#rupaul charles#julio torres#sarah sherman#movie icons#layouts#headers#favorite#aesthetic#troy quane#nick bruno#karen ryan#karen ann ryan#roy lee#julie zackary#robert l baird#lloyd taylor#nd stevenson

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

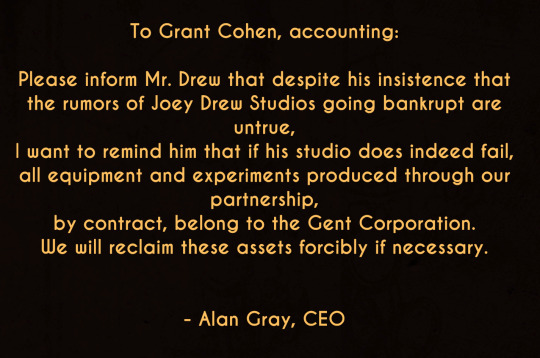

Every single memo in BATDR

Your Best Pal

Sammy Lawrence

Shawn Flynn

Thomas Connor

Wally Franks

Joey Drew

Alice Angel

A Friend (Allison)

Alan Grey

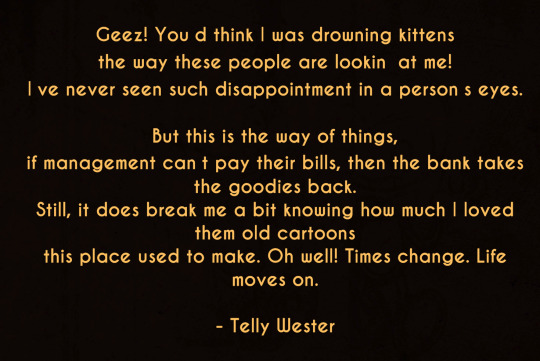

Telly Wester

Sally Newt

Hudson Doyle

Chef Buck

Phil Clark

Muncie Dunn

Eugene Lloyd

Kitty Thompson

Unknown

#bendy spoilers#bendy and the dark revival#bendy and the ink machine#dreamfisher certified#official bendy

296 notes

·

View notes