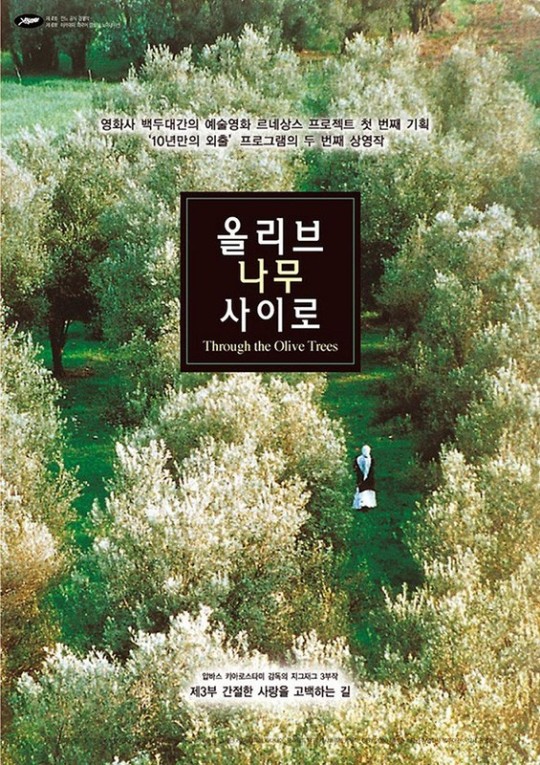

#Farhad Kheradmand

Text

AND LIFE GOES ON:

Director and son

Drives to village he filmed in

Destroyed by earthquake

youtube

#and life goes on#random richards#poem#haiku#poetry#haiku poem#poets on tumblr#haiku poetry#haiku form#haiku on tumblr#criterion collection#abbas kiarostami#life and nothing more#Zendegi va digar hich#Farhad Kheradmand#Buba bayour#Hossein Rezai#Hocine Rifahi#Youtube

1 note

·

View note

Photo

And Life Goes On (Abbas Kiarostami, 1992)

Cast: Farhad Kheradmand, Buba Bayour, Hocine Rifahi, Ferhendeh Feydi, Mahrem Feydi, Bahrovz Aydini, Ziya Babai, Mohamed Hocinerouhi, Hocine Khadem, Maassouma Berouana, Mohammad Reza Parvaneh. Screenplay: Abbas Kiarostami. Cinematography: Homayun Payvar. Film editing: Abbas Kiarostami, Changiz Sayad.

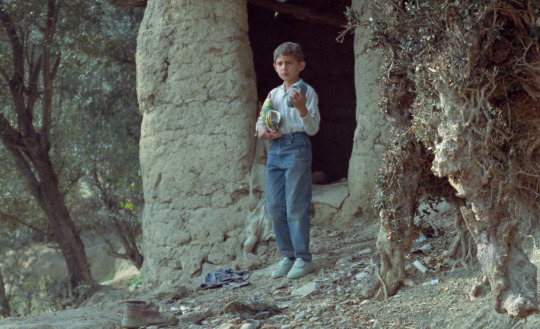

Nothing quite sums up And Life Goes On better than its final sequence. We have followed a film director and his young son on their journey into the earthquake-shattered north of Iran, where the director hopes to find out the fate of the boys who appeared in his earlier film, Where Is My Friend's House? After battling traffic clogged with heavy-equipment clearing the rubble, and being turned onto roads closed by fissures that have opened into the earth or blocked by landslides, he finally finds the road that will take him to the village of Koker, where the earlier film was made. Having been told that his aging automobile will have trouble making it up the steep hills ahead of him, the director passes up a man carrying a heavy burden who asks for a lift. And so we watch from the distant high vantage point of another hill as the car toils up the hill, fails to make it to the top, backs down and tries again, fails again and rolls back down to the bottom. He turns the car back into the direction he came from and drives off screen, just as the man carrying the burden enters the frame and begins his long walk up the hill. He makes it and turns the next corner in the zigzag road. Then the director's car reappears, and building up momentum, makes it to the top, where he picks up the man and continues their journey. It's one long beautiful take, and it encompasses the theme of endurance that is central to And Life Goes On. It's a fictionalized version of Kiarostami's own experience, with actors Farhad Kheradmand and Buba Bayour playing equivalents to Kiarostami and his son. As in many of Kiarostami's films, including Where Is My Friend's House?*, most of the actors are non-professionals, genuine and rough-edged. The suffering of the survivors, almost all of whom have lost one or more family members, is subordinated to their stubborn determination to stay alive, perhaps best demonstrated by a pair of newlyweds whose wedding was interrupted by the earthquake, killing most of the guests, but who went on with the marriage ceremony anyway.

*The Persian title has been translated several different ways: IMDb, for example, calls it Where Is the Friend's Home?

1 note

·

View note

Photo

“Everyone has their own problems.”

And Life Goes On… (Abbas Kiarostami, 1992)

#And Life Goes On…#And Life Goes On#Abbas Kiarostami#Kiarostami#long#shot#Life and Nothing More…#Life and Nothing More#nature#back#1992#earthquake#iran#quote#cars#childhood#Zendegi va digar hich#Farhad Kheradmand#Buba Bayour#Hocine Rifahi#trees

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

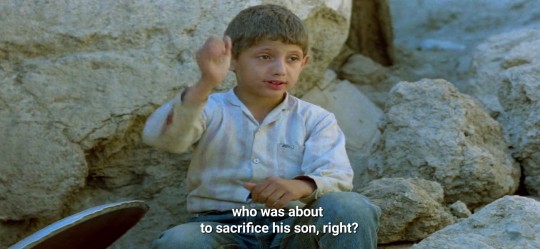

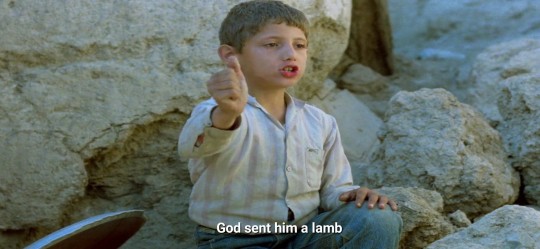

“Well, to continue being alive is also an art”.

Stills from And Life Goes On (also called Life, and Nothing More..., in Persian: زندگی و دیگر هیچ) directed in 1992 by Abbas Kiarostami (Iranian film director, screenwriter, poet, photographer, film producer, b. in Tehran, 1940 – 2016), starring Farhad Kheradmand and Buba Bayour, in the aftermath of the 1990 earthquake in Iran.

#abbas kiarostami#iran#art#iranian film#iranian cinema#And Life Goes On#Life and Nothing More...#زندگی و دیگر هیچ#Farhad Kheradmand#Buba Bayour#book of khidr#bookofkhidr

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Life and Nothing More (And Life Goes on), 1992

dir. Abbas Kiarostami

(2nd part of Koker Trilogy)

#koker trilogy#life and nothing more#and life goes on#films#cinema#abbas kiarostami#art#film stills#cinephiles#drama#tumbrl#earthquake#abraham#praise allah#praise god#cinemetography#farhad kheradmand#buba bayour#tumblrlove#feedmefilm#filmyhit#persian#persian cinema#movies#fav movies

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

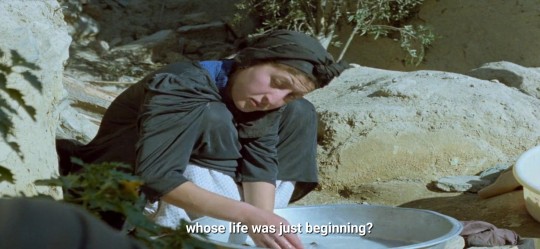

kelimeler, mazlumların yaralarını serinleten merhemlere benzer..

Ercan Kesal, Velhasıl s.38

Fotoğraf: Abbas Kiarostami’nin 1992 yapımı, “Zendegi va digar hich” (Ve Yaşam Sürüyor) filminden.

#zendegi va digar hich#ercan kes#velhası#abbas kiarostami#abbas kiyarüstemi#and life goes on#life and nothing more#زندگی و دیگر هیچ#farhad kheradmand

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

10.27.19

#film#watched#letterboxd#abbas kiarostami#through the olive trees#mohamad ali keshavarz#farhad kheradmand#zarifeh shiva#hossein rezai#tahereh ladanian#hocine redai#zahra nourou#nasret betri#azim aziz nia#astadouli babani#n. boursadiki

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

111. Trilogia Koker: E a Vida Continua (Zendegi va digar hich, 1992), dir. Abbas Kiarostami

#cinema#abbas kiarostami#farhad kheradmand#buba bayour#Iranian cinema#1990s movies#classic movies#koker trilogy#drama#father son relationship#class differences#disaster#earthquake#sequence#non professional actor#road movie#film director#world cinema#cinefilos

1 note

·

View note

Text

Life and Nothing More…/And Life Goes On…, 1991

On a chaotic and congested highway toll interchange, an off-camera toll clerk listens impassively to a humanitarian public service radio broadcast from a Red Crescent spokesperson urging listeners to consider adoption of the many children who have been left orphaned as a result of the recent devastating earthquake in northern Iran. An unnamed, middle-aged film director (Farhad Kheradmand) stops at the tollbooth and inquires about the condition of the main road to Rudbar, having been turned back a day earlier at the intermediate town of Manjil due to the impassability of the route. Accompanied by his son Puya (Puya Pievar), the director is hoping to reach the village of Koker in search of the Ahmadpour brothers: two boys who had appeared in his film, Where is the Friend’s House? (a self-reference to Abbas Kiarostami’s earlier film). However, the director’s plans are soon derailed when a police officer explains that the road is only available for access by emergency and supply vehicles. Attempting to traverse the main road as far as he is able to (and allowed by the emergency authorities to travel on the road), he inevitably finds himself snarled in an interminable traffic juggernaut on the outskirts of Rostamabad. Spotting a convenient rural side road through the hills, he takes an impulsive detour through earthquake-ravaged communities and makeshift tent relief aid centers in search of an alternate route to the remote village and, in the process, encounters a series of aggrieved, but resilient earthquake survivors as they slowly rebuild their scarred lives after the incalculable tragedy.

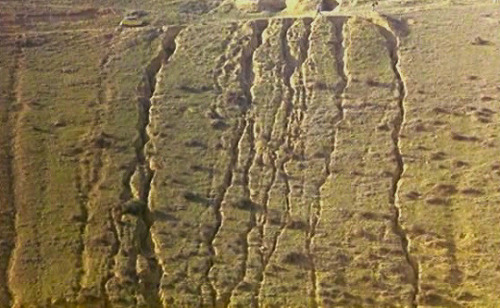

The second film in the Pirandellically interwoven Earthquake Trilogy (along with Where is the Friend’s House? and Through the Olive Trees) that examines – and redefines – the relational perspective between reality and fiction, Life and Nothing More… is an understated, meditative, and celebratory portrait of perseverance, human dignity, and survival. Set amidst the recovery efforts of earthquake-torn northern Iran (note the indelible long shot of the director’s stopped car that reveals the deep crevices on the side of a hill), the film is a metaphoric journey through the process (and procession) of life and renewal: the baby in the forest; the villagers’ continued excavation of their homes (an allusive image of rising from the dust that also appears in a subsequent Kiarostami film, The Wind Will Carry Us); Puya’s innocent, yet pensive and profound rationalization on the life (and spiritually) affirming consequence of tragedy; the newly married couple (Tahereh and Hossein of Through the Olive Trees). The abstractly sublime, lyrical, and uplifting final sequence shows the once-rebuffed hitchhiker ironically aiding the director in extricating his automobile from the side of a hill after stalling during a steep ascent – a haunting and profoundly expressive image of humanity, compassion, and community that continues to exist and persevere against the natural desolation of an austerely beautiful, yet unforgiving and fractured landscape.

0 notes

Text

‘Do you think he’s in there Ali?’

-‘No I don’t see his white car, perhaps not.’

‘Do you think its okay to ring the bell? Or slide in a note?

-‘umm…not a great idea I’m afraid.’

On a brighter afternoon in Tehran, sometime in February I had embarked on a journey to trace the home of Abbas Kiarostami, the person whose cinema inspired my journey from India to Iran, the person whom I never got to really meet in person, but who gave me most of all that I could connect through poetry and cinema. Abbas Kiarostami, one of the greatest masters of Iranian cinema, and perhaps the only one whose influence I directly felt in my life, died yesterday after a series of misdiagnosed and careless surgeries, in Paris.

Abbas Kiarostami, Doors with Leaves Installation Series

While the whole world mourns, and perhaps it is important to mourn now and keep mourning every time we watch his films or read his short poems; almost designed like the fatal shots in our collective lives, we must remember to celebrate loss, and be grateful we were a conscious part of a society that felt, at least for some time.

I felt the deepest passion that afternoon walking through the neighbourhood of Chizar Avenue with a friend, a fellow Kiarostami lover and a ‘stalker-of-a-neighbour’ to the master filmmaker who kept a watch out for Kiarostami in the local shop buying cigarettes; tipping the vendor to intimate him on his arrival.

All for my sake of course.

I had already completed two months in Iran. Now wretched, with all my money exhausted, and almost no hope of a possible meeting with Kiarostami (when I had visited the office of Film, the popular film tabloid, the very kind Persian at my aid warned, ‘I can put you in touch with anyone for your research, just don’t ask for Kiarostami or Farhadi.’) I knew then that I’d have to figure a way out to meet him. I knew he had been in Cuba conducting a workshop, but I was hoping he’d be back, at least before I exhausted my last few hundred tomans. Ali, my friend (and the aforementioned kind neighbour of the ostad) promised to walk me till Kiarostami’s home.I decided to film the walk. A part of me knew he may not be back on time, and perhaps this was the closest I could get to reaching him. On the way to the friend’s home, we kept wondering if it would be polite to ring the bell directly and introduce myself or just slide a letter under his door.

When we reached the house, I just stood still; marvelling at the simplicity in the placement of a pretty two storied house (covered entirely with green creepers) amidst tall buildings on either side.

‘Do you think he’s in there Ali?

-‘No I don’t see his white car, perhaps not.’

‘Do you think its okay to ring the bell? Or slide in a note?

-‘umm…not a great idea I’m afraid.’

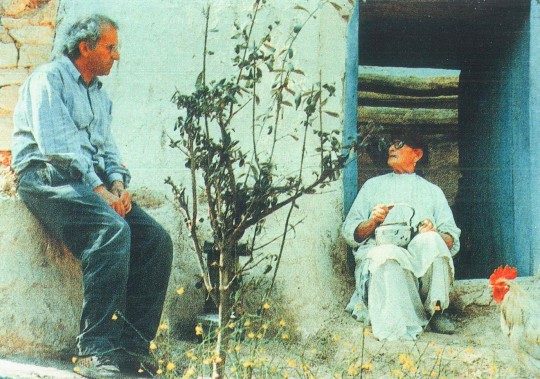

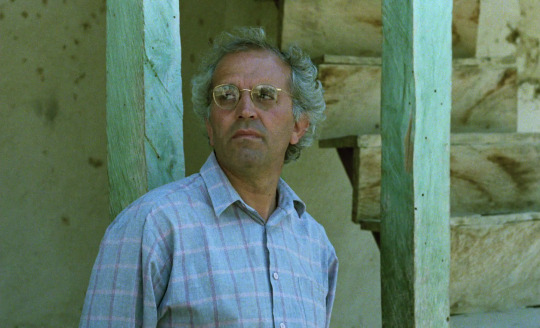

I decided I’d write the perfect note and slide it under his door next day, but it was too late already. Kiarostami was already hospitalised, after being diagnosed with intestinal cancer. I was living with Farhad Kheradmand (actor, Through the Olive Trees, 1994 and Life and Nothing More, 1992) at his house in Tehran that Spring. I remember Farhad broke the news to me with great despair. Recovering from a heart transplant himself, the news was brutal. I remember spending many afternoons with Farhad recounting memories of his days spent with Kiarostami. The most striking one was during the filming of Life and Nothing more. In the film Farhad, enacting the role of the director drives his son through the earthquake stricken region of Manjil in order to find out if the characters of his earlier film Where is the Friends House?, 1990 (Ahmad and Babak) are alive. Farhad recounted that all Kiarostami ever told him was he had to look really disturbed and tense while driving through the barren streets. For achieving this he decided to replace the car in which Farhad had practised driving for over a month with an absolutely different, uncomfortable one. Farhad was naturally tensed throughout the shoot. This in fact made him break into a sweat. Kiarostami was notorious for employing such tactics in order to get his best shots. All his actors had to go through severe mental stress during filming as he would break out the harshest news while filming, but later apologizing by showing them the final shots.

Amad and Babak from ‘Where is the friend’s home?’

Ali’s walk towards the ‘ostads’ house and Farhad’s innumerable memories recounted on my camera were the closest I could get to knowing the ‘ostad’ in his very own land. My real memories would still be the little bits of him that the heart has preserved with every film, the images the mind had conjured by his poetry and the infinite power of feeling the beauty of the spaces captured in his photographs.

Last night thousands of lovers of cinema, filmmakers and actors gathered at the Cinema Museum/Muze ye Sinema in Tehran lighting candles, placing roses on giant sized photographs of the late director, mourning. Among the ones spotted were Jafar Panahi, Khosro Sinai, Rakshan Banietemad, Asghar Farhadi, Homayun Ershadi, Mahtab Keramati, Fatema Motamed Aria.

Kiarostami is said to be brought back to Iran on Friday.

As I’m pained to state these details, my mind wonders off at a sequence from Life and Nothing More where an old man remains immersed in setting up the antenna for watching a football match on TV. He states the necessity of watching the world cup finals which comes only once in every four years, while earthquake, once in forty. The reportage of the earthquake is not sentimentalised but left raw. The barrenness and death of the land is shown in contrast with the spirit of the people. Life must go on.

Autumn afternoon

A sycamore leaf

Falls softly

And rests in its own shadow

Abbas Kiarostami (Walking with the Winds, 2002)

–Sreemoyee Singh

(A Third Year PhD student from the Dept of Film Studies at Jadavpur University, Sreemoyi is working on ‘The national and the translation in the exile cinemas of Iran’. She has lived in Tehran for 3 months to conduct her fieldwork in the course of which she interacted with several filmmakers including the likes of Jafar Panahi, Khosro Sinai, Shirvani Mohammad, Kianoush Ayari and others)

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed within this POV/BLOG are the personal opinions of the author. PANDOLIN is not responsible for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information on this blog. All information is provided on an as-is basis. The information, facts or opinions appearing on the POV/BLOG do not reflect the views of PANDOLIN and PANDOLIN does not assume any responsibility or liability for the same.

Where is the friend’s home? ‘Do you think he’s in there Ali?’ -‘No I don’t see his white car, perhaps not.’

#Abbas Kiarostami#blog#Bollywood#cinema film#Farhad Kheradmand#Farhadi#film-making#Indian cinema#Indian film#iran#iranian cinema#iranian filmmaker#Jafar Panahi#Khosro Sinai#Kianoush Ayari#Kiarostami dead#magazine#make a movie#making a film#making a movie#mandolin#movie making#pandolim#pandolin#pandolin.com#pangolin#Shirvani Mohammad#Tehran

0 notes

Photo

Farhad Kheradmand and Hossein Rezai in Through the Olive Trees (Abbas Kiarostami, 1994)

Cast: Mohamad Ali Keshavarz, Farhad Kheradmand, Zarifeh Shiva, Hossein Rezai, Tahereh Ladanian, Hocine Redai, Zahra Nourouzi, Nosrat Bagheri, Azim Aziz Nia, Ostadvali Babaei, Ahmed Ahmed Poor, Babek Ahmed Poor. Screenplay: Abbas Kiarostami. Cinematography: Hossein Jafarian, Farhad Saba. Production design: Abbas Kiarostami. Film editing: Abbas Kiarostami. Music: Amir Farshid Rahimian, Chema Rosas.

Through the Olive Trees is the concluding film in what has become known as Abbas Kiarostami's "Koker trilogy," which is made up of the neorealistic Where Is My Friend's House? (1987), the semi-documentary And Life Goes On (1992), and this lyrical, pastoral, slyly comic work. It's possible to impose a variety of shapes on the trilogy as it moves from the simple narrative of the first film, made on the eve of the 1990 earthquake that devastated northern Iran, through the anxious quest for survivors of the cast of the first film that constitutes the middle film, and into a kind of post-disaster healing that centers on both the making of a film and one of its actors' nervous, intense courtship of a young woman, also an actor in the film. Through the Olive Trees also answers a question that was raised but never answered in And Life Goes On: Did the two boys who were the focus of Where Is My Friend's House survive the quake? But like most of the questions the third film deals with, the answer is oblique or obscure to the inattentive. In this case, it's a yes: The boys, Ahmed and Babek Ahmed Poor, appear in this film bringing potted geraniums to the set of the film that's being made in post-quake Koker. Kiarostami doesn't identify them as such, but leaves the recognition to viewers familiar with the first film. In fact, it's best to watch the trilogy as a whole, as Kiarostami manages to move actors and characters around among the three films. In Through the Olive Trees, the actor/character known as Farhad is the same actor, Farhad Kheradmand, who played the director in And Life Goes On. A different actor, Mohamad Ali Keshavarz, plays the director in Through the Olive Trees. Sometimes we don't know whether we're watching actors performing in scenes for the film that's being made or the actual lives of the actors out of character -- in fact, the actors find it hard to separate the two. The third part of the trilogy is linked visually to the first by the zigzag path that people traverse to surmount the steep ridge that separates villages. And Through the Olive Trees links visually with And Life Goes On in that both films conclude with remarkable long-shot long takes in which characters from the film encounter each other at great distances from the camera. Taking the three films together, I think, only binds them into a whole masterwork -- an enigmatic, moving, frustrating, fascinating masterwork.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

“We decided to enjoy life while we could. The next earthquake might kill us too.”

And Life Goes On… (Abbas Kiarostami, 1992)

#And Life Goes On…#And Life Goes On#Abbas Kiarostami#Kiarostami#quote#Life and Nothing More…#Life and Nothing More#childhood#iran#sequel#cinema#cars#road movie#Buba Bayour#Farhad Kheradmand#Zendegi va digar hich#earthquake#coke#death

688 notes

·

View notes

Photo

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Films watched in 2021.

132: And Life Goes On… (Abbas Kiarostami, 1992)

★★★★★★★★☆☆

“He was in the movie!”

#Films watched in 2021#And Life Goes On…#And Life Goes On#1992#ocho#Abbas Kiarostami#Kiarostami#Life and Nothing More…#quote#iran#documentary#Life and Nothing More#Zendegi va digar hich#drama#earthquake#cinema#road movie#sequel#Buba Bayour#Farhad Kheradmand#Khane-ye Doust Kodjast#movie#cars#hands

420 notes

·

View notes

Photo

And Life Goes On… (Abbas Kiarostami, 1992)

#And Life Goes On…#And Life Goes On#Abbas Kiarostami#Kiarostami#Zendegi va digar hich#Farhad Kheradmand#Buba Bayour#quote#cinema#film#house#home#1992#Life and Nothing More…#Life and Nothing More#movie#destruction

246 notes

·

View notes

Text

Review: Abbas Kiarostami’s The Koker Trilogy on Criterion Blu-ray

This magnificent set of essential restorations is a strong contender for Blu-ray release of the year.

by Chuck Bowen on

October 31, 2019

The films in Abbas Kiarostami’s Koker trilogy have a sense of immediacy—an in-the-moment exactitude—that adds up to an expansive vision of life. After watching Where Is the Friend’s House?, And Life Goes On, and Through the Olive Trees, especially in close succession, it may feel as if you’ve actually navigated the Iranian farming village of Koker, perhaps even strolled the iconic zig-zag trail up a hill to what appears to be the neighboring village of Poshteh. In these films, Kiarostami revels in narrative, pictorial, and verbal patterns, which he revises to express the open-endedness of life, as well as the porous boundaries between “reality” and art. The master filmmaker also fuses documentary and fiction, elaborating on the strengths and limitations of each form, suggesting that documentary is fiction and vice versa.

Throughout the trilogy, Kiarostami keeps allowing people’s identities to fluctuate (for instance, a major character in one film might be an extra in another), with lines between scripted and “found” roles consciously blurred. This instability cumulatively communicates the changes wrought by the passage of time, and so the characters’ shifting identities render them more lifelike than the cemented stereotypes of TV shows and conventional movie sequels. Yet amid this fluctuation is the seeming permanency of that zig-zag trail, of a grove of olive trees, of a porch outside a fierce grandmother’s home, of landscapes that embody the Sisyphean comedy of everyday travails that come to mean everything.

The loose narratives of these three films offer another sort of permanency, as they all concern a variation of the same plot, following a protagonist who’s thwarted in his quest to communicate a message to another party. And none of these protagonists achieve their quest the way they had imagined, and this frustration acquaints them with the mystery and majesty of the quotidian of their lives, allowing them to integrate with their society.

In Where Is the Friend’s House?, Kiarostami spins one of the greatest of all films out of a child’s urge to return a notebook to his classmate. Dramatizing this dilemma, Kiarostami offers a tapestry of life, revealing how the domestic textures of Koker embody its class issues and politics. Trying to find his friend, Ahmad (Babak Ahmadpour) navigates multiple definitions of authority and varying generations of his family and neighbors. At first, Ahmad regards adults as impediments to his generosity, though the boy gradually comes to see that these men and women have their own vulnerabilities, which Kiarostami expresses in images of rapt beauty. The filmmaker renders common acts, such as an elderly craftsman’s task of taking off his shoes by his doorway, as emotionally revelatory moments of process.

And Life Goes On and Through the Olive Trees are wilder and more free-wheeling than Where Is the Friend’s House?, pondering the ramifications of the earlier film’s existence. In And Life Goes On, a filmmaker (Farhad Kheradmand) clearly modeled on Kiarostami searches for the children who appeared in Where Is the Friend’s House in the wake of the real-life earthquake that devastated Koker in 1990. In Through the Olive Trees, another Kiarostami stand-in (Mohammad Ali Keshavarz) shoots And Life Goes On, getting stuck on a vignette that reveals the real romantic tensions between two of his moonlighting non-actors. The films nest inside one another, freeing Kiarostami from the (comparatively) traditional plotting of Where Is the Friend’s House? With this freedom, Kiarostami creates sequences that are interlocked and isolated at once, existing as stanzas that are both journalistic and figurative.

The tedium of conventional three-act narratives rests in a certain rigidity: Most stories are equations with dilemmas that must be resolved as one might a proof, and to make such equations work, most filmmakers shortchange the spontaneous, ambiguous, sensual textures that are the manna of life. Kiarostami has it both ways, using formal patterns to convey stability, and to give us reassurance of the familiar, while abandoning plots to pursue his more original fancies. In And Life Goes On, there’s a powerfully pragmatic and intimate scene where a husband (Hossein Rezai) explains he and his wife’s need to marry in the face of tragedy, as well as a moment of profound insight in which a young man explains his need to watch the World Cup even among the ruins wrought by the earthquake. And in Through the Olive Trees, there’s a poignant yet piercingly unsentimental moment in which an illiterate villager pleads for the necessity of intermarrying between the rich and poor. Desperate to transcend himself, he’s both classist and self-loathing, willing to breed his people out of existence.

Above all, Kiarostami’s intermixing of fact, fiction, and metatextual confessional affords him and his audience space. These films have dozens of extraordinary moments in which narrative and time seemingly freeze to allow us to register characters’ complex reactions to common stimuli. Some of these sequences are simple and rapturous, such as a close-up of a soda bottle as a boy buys it from a store deserted in the wake of the earthquake; others are troubling and profoundly moving, such as a lingering medium shot of Ahmad as it dawns on him that he has his friend’s notebook, which could get the friend expelled. In the latter scene, we see the crystallization of this boy’s morality as well as his calculation of the perils of honoring it, and Kiarostami accords this moment its full weight without rushing along to tend to the plot. The true story of the Koker trilogy are such poetic moments of extremity, ones that seemingly arise out of nowhere and force us to reckon with the tenor of our existence.

Image/Sound

Criterion’s restoration and promotion of these films, given their relative obscurity in the West, is good news in itself, though the better news is the formal magnitude of these transfers. The images are pristine, with vibrant and varied colors and healthy grit. The textures of characters’ faces and of Koker’s natural landscapes are stunning, especially the rugged mountains and trees. The soundtracks are also impressive, particularly underscoring Kiarostami’s masterful use of diegetic sounds to establish a sense of place—especially the noises made by domestic animals and machines, such as construction equipment and cars. Dialogue is clear, unless it’s not meant to be, and music is rendered with clarity and a becoming lightness of body.

Extras

These extras offer a wonderful examination of the films in the trilogy and their larger cultural context. For a wide-reaching discussion of Iran’s political textures, and of Kiarostami’s use of varied perspectives, the new audio commentary on And Life Goes On with Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa and Jonathan Rosenbaum, co-authors of Abbas Kiarostami, makes for invaluable listening that will be especially useful for Western audiences. Complementing the commentary are a variety of new interviews, such as the conversation between scholar Jamsheed Akrami and critic Godfrey Cheshire, in which the men wrestle with Kiarostami’s style and the use of the word “trilogy,” and an incisive discussion with scholar Hamid Naficy. Meanwhile, another new interview with Kiarostami’s son, Ahmad, offers a more personal perspective, while a 2015 interview with Kiarostami himself abounds in choice descriptions, such as his approach to non-actors: “They were not acting, they were living in front of the camera.”

A 1994 documentary, Abbas Kiarostami: Truths and Dreams, follows the filmmaker in Koker after the trilogy’s completion, and nearly functions as a sequel to the original films. Even better, Kiarostami’s 1989 documentary Homework is included here; it’s essential for helping to elaborate on the evolution that his filmmaking process was undergoing at this time. (Another critical film in Kiarostami’s canon, Close-Up, was a pivotal influence on And Life Goes On and Through the Olive Trees, and is prominently mentioned by many of the writers on this set.) Rounding out this essential collection of extras is a booklet featuring an essay by Chesire that beautifully encapsulates the complex humanist structure of these classic films.

Overall

This magnificent set of essential restorations, accompanied by passionate and well-researched supplements, is a strong contender for Blu-ray release of the year.

Cast: Babek Ahmed Poor, Ahmed Ahmed Poor, Khodabakhsh Defaei, Iran Outari, Ait Ansari, Sadika Taohidi, Biman Mouafi, Ali Djamali, Aziz Babai, Farhad Kheradmand, Buba Bayour, Hocine Rifahi, Ferhendeh Feydi, Mahrem Feydi, Bahrovz Aydini, Ziya Babai, Mohamed Hocinerouhi, Hocine Khadem, Mohamad Ali Keshavarz, Zarifeh Shiva, Hossein Rezai, Tahereh Ladanian, Hocine Redai, Nosrat Bagheri, Azim Aziz Nia Director: Abbas Kiarostami Screenwriter: Abbas Kiarostami Distributor: The Criterion Collection Running Time: 281 min Rating: NR, G Year: 1987 - 1994 Release Date: August 27, 2019 Buy: Video

#The Criterion Collection#Abbas Kiarostami#عباس کیارستمی#Where Is the Friend’s House?#خانه دوست کجاست#Through the Olive Trees#زیر درختان زیتون#Life and Nothing More...#And life goes on...#زندگی و دیگر هیچ

0 notes