#Flavoparmelia

Text

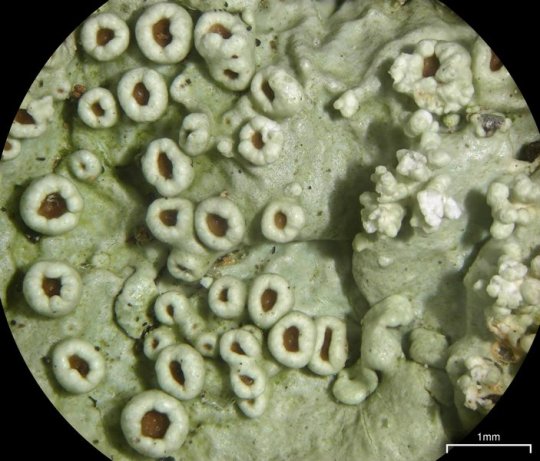

Flavoparmelia soredians

A positive story for today! F. soredians is sensitive to pollution--particularly sulfur dioxide. Now generally in our modern age, lichen populations which are sensitive to pollution have been decreasing. But recently, observers and scientists have actually noticed populations of this lichen increasing! This trend follows trends in decreases in environmental sulfur dioxide pollution, and so this goes to show that if we reduce environmental pollution, lichen populations can bounce back! This foliose lichen grows in closely-attached rosettes up to 10 cm in diameter. The upper surface is yellow-green, and speckled with farinose soredia bursting from round or ridge-like soralia. The lower surface is black towards the center and brown toward to lobe margins, and has simple rhizines. It only rarely produces apothecia, which are saucer-shaped with a brown disc and sorediate margin. F. soredians grows on trees, wood, and occasionally rock and roofs. It has been recognized thus far in Europe, North America, and Australia, but who knows where its range might expand to next!

images: source | source

info: source | source | source | source

#lichen#lichens#lichenology#lichenologist#fungus#fungi#mycology#ecology#biology#botany#bryology#forestry#pollution#conservation#Flavoparmelia soredians#Flavoparmelia#I'm lichen it#lichen a day#daily lichen post#lichen subscribe#life science#environmental science#natural science#nature#naturalist#beautiful nature#weird nature

136 notes

·

View notes

Photo

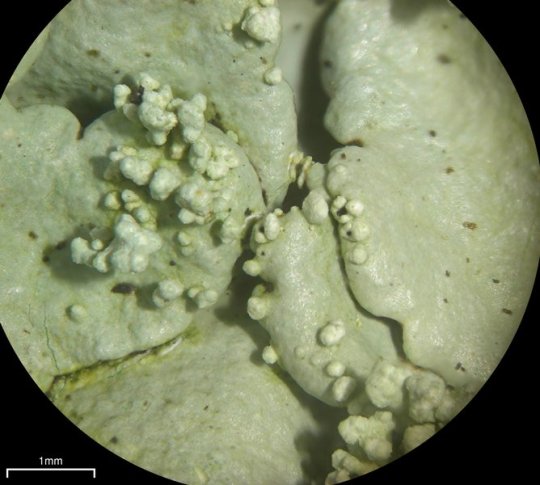

Some super common macro lichens in the midwest you can readily learn. Generalized to mainly wood surface and not super generalized on rock.

Common Greenshield Lichen, Flavoparmelia caperata

vs

Punctelia rudecta, and recent split Punctelia missouriensis (see those white speckled lobes. during full developement and we see a different colored isidiate core. this is why it’s commonly known as the rough speckled shield ) (this concept can be seen in the lower specimen.) (The upper though developes consistently less isidiate core and instead has overlapping squamulobes which gives it a mealy look.) (Called Mealy Speckled Shield lichen.)

What isn’t as common is large thallus mats with proper apothecia developement. Its like a light blue core if it’s the case unlike moon glow lichen which has a brown apothecia core and smooth axle bristle which looks green when hydrated and has an orange like tint when dry. imishaga doesn’t seem to produce apothecia or an isidiate core while rough speckled can produce both though the apothecia are supposed to be small like seen above on this Quercus muehlenbergii

the green shield will be smooth, baltimore green shield is a rock species where as smooth(rare) and common are both on wood, not an isidiate display, and fully same colored thallus wet or dry.

the bottom picture is the two colored thallus of rough speckled sheild without an isidiate core that i put water on to see if i could get hydrated colors.

#shield macro lichen#punctelia rudecta#punctelia#flavoparmelia#flavoparmelia caperata#lichen#ohio#botany#mycology#punctelia missouriensis#macrolichens#macrolichen#arborculture

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

FOTD #130 : common greenshield lichen! (flavoparmelia caperata)

common greenshield lichen is a foliose lichen in the family parmeliaceae. it often grows on rocks & the bark of trees around the world :-) it is notably quite resistant to air pollution.

the big question : can i bite it??

this lichen is non-poisonous !!

f. caperata description :

"the common greenshield is fairly easy to spot : it looks somewhat like a leaf of lettuce glued to the side of a tree. its upper surface is usually pale yellow-green, but it becomes a deeper green when wet. the edges of the common greenshield are broken up into rounded lobes. these lobes are smooth when the lichen is small, but soon become wrinkled in medium to large specimens. towards the centre of the lichen, you will notice irregular rough patches."

[images : source & source]

[fungus of the day : source]

#• fungus of the day !! •#[flavoparmelia caperata]#: common greenshield lichen :#130#||#mycology#fungus#cottagecore#foraging#nature#fungi#earth#forestcore#lichen#fotd#fungus of the day#flavoparmelia caperata#common greenshield lichen

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

Meanwhile - MOSS and LICHENS

It's been warmer and very rainy the past few days, so the Starry Bristle Moss (orthotrichum stellatum) near where I get the bus in the morning is all out and plumped up. Back in 2019 I posted some pics along with what it looks like when it's dry out (it's not nearly as green and lush.)

I love getting to say hi to it when it's out and enjoying the damp and wet weather like this. It's so cute!

Nearby trees have a lot more lichen than moss on them. (They have SOME moss; while the trees with the large amount of moss have SOME lichens, but it seems like an either-or thing.)

Fairly sure that the light green, larger one is common greenshield lichen (Flavoparmelia caperata).

What I can't figure out yet is the very yellow-green stuff. I'm not even sure if it's a lichen, or a moss. Or something else? In the bottom-left photo, as I zoom in, I THINK that some of the more yellow-green bits MIGHT be young versions of the grey-green greenshield lichen??? But the bottom right photo seems like a completely distinct population (on another tree).

I'm not finding anything comparable in some preliminary searches. Will keep trying, but if anyone has any clues, give me a shout!

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

id uncertain, possibly a very small Flavoparmelia caperata?

1 note

·

View note

Photo

On a bleak, gray December afternoon, the best color on Brown’s Hill in the Mason-Dixon Historical Park was provided courtesy of its lichen, moss, and fungi. From top: Lipstick powderhorn lichen (Cladonia macilenta), also known as scarlet pin lichen; turkey tail mushroom (Trametes versicolor), with a green cast caused by an algae; Dixie reindeer lichen (Cladonia subtenuis), the most common of West Virginia’s five reindeer lichens; common greenshield lichen (Flavoparmelia caperata), which most frequently grows on tree trunks; and rock greenshield lichen (Flavoparmelia baltimorensis), which grows primarily on sedimentary rock.

#appalachia#vandalia#west virginia#pennsylvania#lichen#fungi#mason-dixon historical park#cladonia#lipstick powderhorn#turkey tail#trametes#flavoparmelia#common greenshield lichen#rock greenshield lichen

445 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Nice collection of lichens on the venerable rocks at Indian Rock Park in Berkeley. #dustlichen #lepraria #goldspecklichen #candelariella #greenshieldlichen #flavoparmelia #sunkendisklichen #aspicilia https://www.instagram.com/p/B7JY1TkgWAC/?igshid=jqx2k1q8t7f

#dustlichen#lepraria#goldspecklichen#candelariella#greenshieldlichen#flavoparmelia#sunkendisklichen#aspicilia

32 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Common Greenshield Lichen, Flavoparmelia caperata (by me)

#Common Greenshield Lichen#Flavoparmelia caperata#Flavoparmelia#Parmeliaceae#Lecanorales#Lecanoromycetes#Ascomycota#Fungi#lichen#summer#Stony Brook-Millstone Watershed Reserve#Mercer County#New Jersey#mine

23 notes

·

View notes

Note

tells us more about lichenology please

i'm by no means a scientist or even educated in biology past the most rudimentary high school level so my understanding and study of lichens is that of an artist and layperson.

my focus has been on the use of lichens for textile dyeing specifically, but in order to ethically and correctly collect lichen for dyeing i have to be able to identify them at least by their genus for a few major reasons. primarily, as an artist, different species need to be processed in different ways to produce colours unique to them. some species don't produce any colour when processed one way and produce vivid colour in another; others produce wildly different colours in different contexts. secondarily, from an ecological perspective, its important to know how common/rare different lichen are so you don't unknowingly destroy a rare and old organism, and there are ways of harvesting parts of lichen without damaging the thallus or body of the lichen so it can continue to grow if you learn how to do so but it's best to collect lichen that have already fallen off their substrate or are on substrate soon to be destroyed (ex. fallen trees, lumber, etc.)

[image id: diagram showing the various common types of lichen growing on a bark or tree substrate: crustose or crusty lichen, foliose or leaf-like lichen, and frucitose or bushy lichen. the crustose lichen are very flat and bumpy, while the foliose lichen have flat little leaf-like parts branching across the bark. the bushy lichen sticks out from the bark and can resemble either a shrubby moss ball or a large branching piece of coral. /end id]

as organisms, lichen are weird because they're not one singular organism but rather a composite of algae or cyanobacteria and fungal spores that spontaneously develop a symbiotic relationship with each other and become something that is neither algae nor fungi but its own 'thing' altogether with unique characteristics. they are so complex that they can be considered mini ecosystems within themselves. they come in a variety of forms but the most common are crustose, foliose, and frucitose. many lichen species look very similar with minor differences that can only be ascertained through chemical testing (ie. placing a drop of specific chemicals on the thallus and seeing what colours appear), while others are more easily identifiable. some resemble moss and are often mistaken for moss, but they are fundamentally different organisms.

different species are native to different habitats and all lichen species use specific surfaces as their substrate (bark, rocks, soil, etc.) these are photos i took the other day in southern ontario, canada, and the lichens in both images use bark as their substrate. all of the lichen i've identified so far are foliose, or leaf-like, lichen.

[image id: the image on the left shows a bright yellow circular lichen that i've identified as xanthoria parietina (common sunburst lichen) while the image on the right shows pale grey branching lichens that i've identified as physcia stellaris (star rosette lichen). /end id]

there are 3 ways of processing lichen for dyeing: the boiling water method, ammonia method, and photo-oxidation method. boiling water method is exactly how it sounds and is the most common method used in natural dyeing; it typically produces yellows, oranges, and deep rusty browns/reds. the ammonia method requires filling a jar with a mixture of lichen, household ammonia (historically it was urine) and water and shaking the jar every day to oxygenate the mixture, turning the lichen acids into dye pigment; this is left to 'ferment' over the course of weeks or months, depending on the species, amount of oxygen, and amount of lichen. over time the mixture eventually produces dyes that are vivid neon pinks and purples. the final type is photo-oxidation, which only works with a few specific genera of lichen, as they contain an interesting UV-reactive acid that causes things dyed with them to go from pink to purple to bluish-grey when exposed to sunlight.

[image id: a flatlay showing seven bundles of various yarns dyed with lichen. the leftmost yarn is bare white and undyed, the next two are bright pink and purple, and the last four are various shades of greenish-browns and orange. in each bundle there is a thicker yarn that is highly pigmented and a few other thinner yarns that are more pale in colour. /end id]

there are different ways of figuring out the dyeing process required for each lichen species, the most involved of which is the same chemical test method mentioned above. i won't go into detail about the chemistry aspect because i don't have my book on it to reference right now, but essentially, specific chemical reactions tell you what dye pigments a lichen species will produce when processed. for example, the xanthoria (above left) is a species that contains the UV-reactive acid that means fibre dyed with it will photo-oxidize. the physcia is a boiling water method lichen that produces yellows dye.

here are some other lichens i recently identified: the light grey flat branching lichen is called parmelia sulcata (common shield lichen) and it produces reddish-brown dye using the boiling water method. various indigenous peoples of north america use it as a medicine; the metis have used it to soothe the gums of teething babies and the wsanec people use it for a variety of ailments depending on the tree it was harvested from. the very similar looking pale green lichen is called flavoparmelia caperata (common greenshield lichen) and it makes a very pale yellowish-brown dye using the boiling water method.

i'm still learning and have yet to actually collect lichen for dyeing as i've been primarily practicing identification and learning more about the various dyeing processes and the chemistry of it in my free time so any of my identifications could be wrong but i feel fairly confident in them overall.

#long post#lichen#mycology#tex help#deepest apologies to anyone scrolling past this monstrosity of a post <3

361 notes

·

View notes

Text

I spend a lot of time walking around outside my apartment, and I often find some Special Friends growing all over the place. Here are some of them I’ve photographed and identified so far (I will be adding more to this list over time if I can find & ID other species):

1) Fly Agaric (Amanita muscaria)

2) Octopus Stinkhorn (Clathrus archeri)

3) Common Puffball (Lycoperdon perlatum)

(NOTE: This one’s also nicknamed The Devil’s Snuffbox or Wolf’s Farts, funnily enough! A hole opens up in the top to spew out spores. If you squeeze one, you can get some extra spores to spew out)

4) Death Cap (Amanita phalloides)

(NOTE: Earned it’s name from killing those that ingested it)

5) King Alfred's Cakes (Daldinia concentrica)

(NOTE: It’s the black lumps)

6) False Turkey Tail (Stereum hirsutum)

7) Turkey tail (Trametes versicolor)

8) The Sickener (Russula emetica)

(NOTE: This one earned its name because ingesting it can induce vomiting)

9) Brown Jelly Fungus (Tremella foliacea)

(NOTE: This is a parasite to Stereum hirsutum (false turkey tail)! Neat, right?)

10) Lumpy Bracket (Trametes gibbosa)

11) Sulfur Tuft (Hypholoma fasciculare)

12) Dog Vomit Slime Mold (Fuligo septica)

(Closeup included for extra detail, the structure is gorgeous)

13) Common Greenshield Lichen (Flavoparmelia caperata)

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

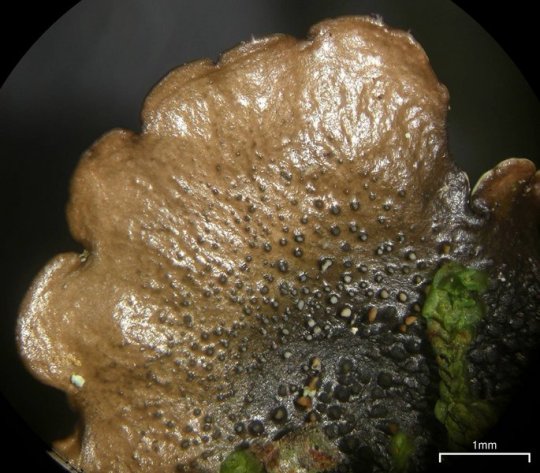

Flavoparmelia baltimorensis

Rock greenshield lichen

Back from vacation and back on my lichen bullshit! This foliose lichen has smooth, yellow-green lobes dotted with pustules across the upper surface. The lower surface is brown-black, with simple, black rhizines. It produces small, pustule-like, brown-disked apothecia. F. baltimorensis grows on acidic rock in eastern and SW North America.

images: source | source

info: source | source

#lichen#lichens#lichenology#lichenologist#lichenized fungus#fungus#fungi#mycology#ecology#biology#botany#bryology#systematics#taxonomy#lichen a day#daily lichen post#Flavoparmelia baltimorensis#Flavoparmelia#life science#environmental science#natural science#nature#naturalist#beautiful nature#weird nature#I'm lichen it#lichen subscribe#go outside#take a hike#look for lichens

181 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Flavoparmelia caperata

common on trees, yellowish green when wet, blueish green when dry, a very common species on most trees, often confused with

Flavoparmelia baltimorensis

or Baltimore green rock shield lichen; the ladder grows on rocky substrate, F. caperata is wood. I guarantee you’ve seen both multiple times in your life.

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

joe is such a good teacher!

we met at GPEP and had a short presentation about the differnt types of lichen and there characteristics

we then went on a hunt to find as meny lichens as we could

i tryed really hard to learn a few of the commen ones like xanthiria and flavoparmelia

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

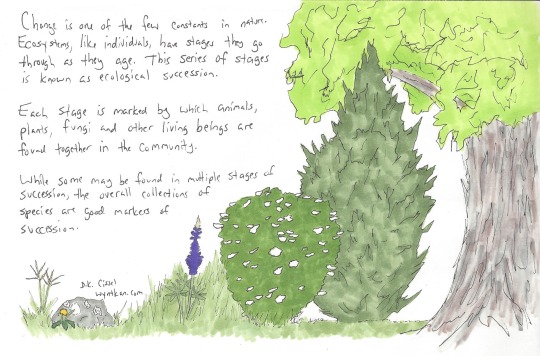

For a lot of people, a bunch of trees in a place counts as a “forest”. Yet those of us who have a more ecological eye can take a look at those trees and figure out whether they’re an established forest, or whether they’re in a younger stage of succession, just by looking at the age of the trees and the various species of living being represented. Other ecosystems may be a bit more challenging to assess, but they have their own chains of succession as well. And as I explained in my comic on old growth forests, not all species can live in a younger, recovering ecosystem. So consider this comic a very basic introduction to the idea that there’s more to a given habitat than what immediately meets the eye!

Also, I had a lot of fun drawing new ecosystems I’ve never tried before! I’m especially proud of my portrait of Loowit (Mt. St. Helens.)

Species portrayed: Plains zebra (Equus quagga), yellow-billed oxpecker (Buphagus africanus), acacia tree (Acacia sp.) big bluestem grass (Andropogon gerardii), common dandelion (Taraxacum officinale), greenshield lichen (Flavoparmelia caperata), wild lupine (Lupinus perennis), arrowwood viburnum (Viburnum dentatum), eastern red cedar (Juniperus virginiana), shagbark hickory (Carya ovata), Pacific bleeding heart (Dicentra formosa), mountain chickadee (Poecile gambeli), noble fir (Abies procera), beargrass (Xerophyllum tenax), wild strawberry (Fragaria virginiana), saguaro cactus (Carnegiea gigantea), prickly pear cactus (Opuntia ficus-indica), mesquite (Prosopis sp.), paloverde (Parkinsonia sp.), paintbrush (Castilleja sp.), northern pocket gopher (Thomomys talpoides), northern red snapper (Lutjanus campechanus), green brittle star (Ophiarachna incrassata), assorted corals

Transcript under cut.

Title: What is Ecological Succession?

[First panel: a scene with a plains zebra with two oxpecker birds on its back, and an acacia tree in the background. The exact same scene is replicated four times with the years 5000 B.C., 1000 B.C., 1800 A.D. and 2020 A.D. under each.]

It’s common to think that ecosystems don’t change, and that what you see today is what’s always been. Yet that isn’t the case.

[Second panel: a forest at different points of succession, with grasses and small herbaceous plants on the left, larger shrubs and small trees in the middle, and a large hickory tree on the right]

Change is one of the few constants in nature. Ecosystems, like individuals, have stages they go through as they age. This series of stages is known as ecological succession. Each stage is marked by which animals, plants, fungi and other living beings are found together in the community. While some may be found in multiple stages of succession, the overall collections of species are good markers of succession.

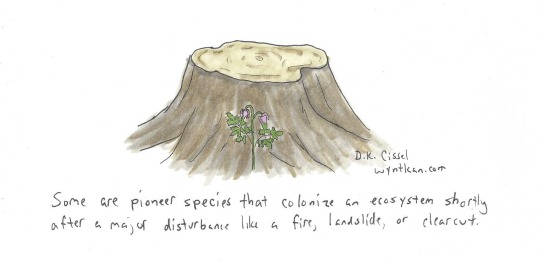

[Third panel: A Pacific bleeding heart flower grows in front of an old tree stump.]

Some are pioneer species that colonize an ecosystem shortly after a major disturbance like a fire, landslide, or clearcut.

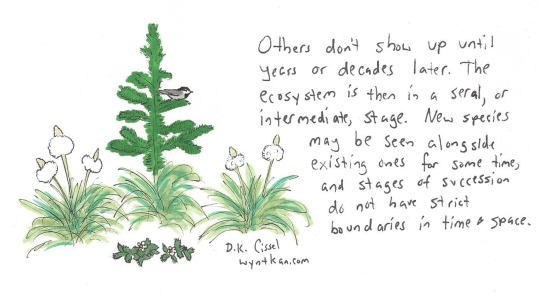

[Fourth panel: A small noble fir tree has a chickadee in its branches, while beargrass and wild strawberries grow nearby]

Others don’t show up until years or decades later. The ecosystem is then in a seral, or intermediate, stage. New species may be seen alongside existing ones for some time, and stages of succession do not have strict boundaries in time and space.

[Fifth panel: a desert scene shows saguaro cactus and prickly pear cactus in the foreground with mesquite and paloverde shrubs behind them, and a ridge in the background]

It may be centuries before the ecosystem reaches its climax stage. At this point, the variety of species living there becomes more or less stable. The living beings also maintain good balance with their physical habitat, including the hydrological cycle (what happens to water in the ecosystem) and the nutrient cycle (how nutrients pass from one being to another.) It remains stable until another disturbance occurs.

[Sixth panel: the foreground shows a northern pocket gopher on a rock next to some paintbrush flowers and grass; behind the hills in the background, Mt. St. Helens shows its giant post-eruption crater]

There are two main types of succession. Most of what I’ve covered so far is secondary succession, when an existing ecosystem is damaged. Primary succession is when a totally new ecosystem is formed, such as when sand dunes expand to new territory, or when volcanic lava cools to create new land. Both types can happen in the same place. For example, the 1980 eruption of Mt. St. Helens in Washington completely wiped out ecosystems directly around the volcano, as did mudflows in some areas further out. All life was destroyed in these places. Yet many other areas, while badly daamged by ash, pyroclastic events, and mudflow, still saw some living beings survive to repopulate. Mt. St. Helens Volcanic Monument protects this patchwork of primary and secondary succession examples, and scientists gather valuable data on both here.

[Seventh panel: a red snapper fish and a green brittle starfish live in a vibrant coral reef with many types of coral]

All ecosystems have succession. More fragile ones like deserts, wetlands and coral reefs, may take longer to recover from disturbances. This is why it is so important that we carefully consider the impact of our actions before we do something that damages or destroys an ecosystem. The wrong choice may mean it will be many lifetimes before the place we’ve harmed recovers entirely--if ever.

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

TINCTORIALES :: Lichens

09/03/21

Récolte pour teinture naturelle de Xanthonia paretina, mélangée avec Evernia prunastri et un tout petit peu de Flavoparmelia sur un saule mort que je débite en bois de chauffage

1 note

·

View note

Text

iNaturalist scavenger hunt in progress:

1. An example of camouflage Dissosteria carolina https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/32118157

2. A plant growing out from the water Typha sp. https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/32218674

3. A mushroom Laetiporus cincinnatus https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/32079695

4. A fish https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/32459139

5. A pupa

6. Something fuzzy Bombus sp. https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/31796490

7. Something spiky Bur-cucumber https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/31796483

8. Something having a meal Attevia aurea https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/31796488

9. A symbiotic relationship Flavoparmelia caperata https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/32118352

10. Something growing on or out of a man-made object https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/32485738

11. An animal with more than 8 legs

https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/32501614

12. An animal with no legs

https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/32501694

13. Something that lives in a shell

https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/32501694

14. Something yellow and black Eristalis sp. https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/31800119

15. Something brown and white Eris militaris https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/32218707

16. Something purple and green Arctium sp. https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/32219619

17. Something really common in your area Xylocopa virginica https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/31796491

18. Something not native to your area Megachile sculpturalis https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/31800567

19. A bee native to your area Agapostemon virescens https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/31800534

20. Something classified as a threatened species Aesculus hippocastanum https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/32234131

21. A feather Quiscalus quiscula https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/32120238

22. An animal track https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/32459051

23. Mating behavior https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/31800132

24. A plant gall Hormaphis hamamelidis https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/31810630

25. A leaf mine Phytomyza persicae https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/31930719

6 notes

·

View notes