#Florida Museum of Natural History

Text

Carnivoran skulls from the Florida Museum of Natural History:

Lesser short-faced bear (Arctodus pristinus). Became extinct around 300,000 years ago, fossils are found in high concentrations in Florida. Related to the modern spectacled bear.

Ambruster’s wolf (Canis ambrusteri). Became extinct around 250,000 years ago, found throughout the United States. Taxonomy of this species is somewhat confusing, it may be related to modern grey wolves but may also be ancestral to dire wolves (which are now placed in the genus Aenocyon).

American lion (Panthera atrox). Became extinct around 11,000 years ago, found from Canada and the United States to southern Mexico. American lions were the sister species to Eurasian cave lions and are closely related to modern lions.

Sabertooth cat (Smilodon gracilis). Became extinct 500,000, had a fairly cosmopolitan range throughout North America and parts of South America. S. gracilis is the smallest Smilodon species and is believed to be the ancestor of S. fatalis and S. popular or. Sabertooth cats are not closely related to any modern species of cat.

#natural history#paleontology#florida museum of natural history#short faced bear#extinct wolf#smilodon#sabertooth#american lion

446 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Group of monarch butterflies

Credit: Florida Museum of Natural History/Photo by Kristen Grace

#kristen grace#photographer#florida museum of natural history#monarch butterfly#butterfly#insect#nature

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

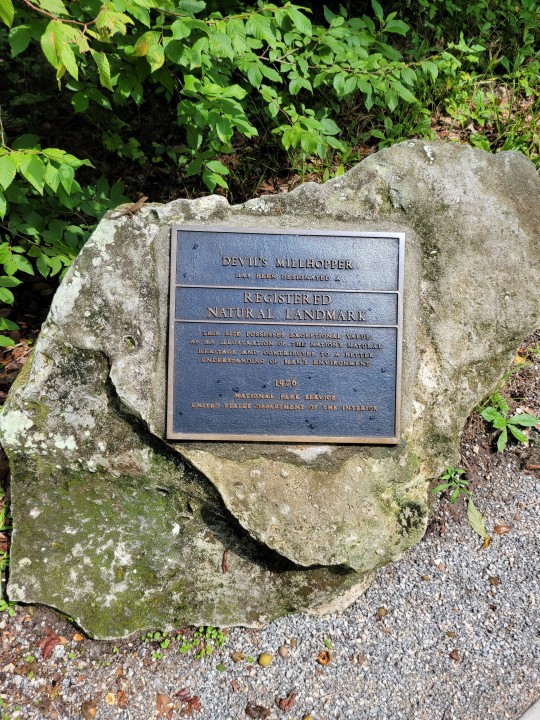

We had a wonderful time exploring in nature in Gainesville. The butterfly house at the Natural History Museum is a must see! Plus we visited Devils Millhopper State Park where we got to see and 10,000 year old sinkhole. On our hike there, we even saw a deer up close! It was a magical trip.

#i am constantly reminded that sometimes florida is pretty cool#travel#florida#gainesville#the swamp#natural history museum#butterfly house#butterfly#devils millhopper#state park#nature walk#hike

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Vickers Family Reception at the Harn Museum

Surrounded by family and friends, Samuel and Roberta Vickers celebrate the opening "A Florida Legacy: Gift of Samuel H. and Roberta T. Vickers” exhibit showcasing the Vickers family over 140 piece art collection gifted during a reception for the to the Harn Museum of Art at the University of Florida.

“The Vickers Collection is unique in its power to convey both the exquisite natural beauty and the rich history of people in Florida — the ruggedness and grandeur of its landscapes and the highs and lows of its human history through the centuries,” UF President Kent Fuchs said. “Sam and Robbie have shared a treasure with us, and we are thrilled to have the privilege of sharing their collection in turn with all visitors to the Harn Museum.”

As an integral part of the University of Florida campus, the Harn Museum of Art will share the Vickers’ gift as an important new resource to strengthen faculty collaboration, support teaching and enhance class tours, and provide research projects for future study. “A Florida Legacy” is organized along six thematic sections that address many prominent subjects represented in the Vickers Collection: nature, history, landmarks, diversions, living and impressions.

The “Florida Nature” section includes iconic views of Florida forests, beaches and wetlands.

The “Florida History” section includes nineteenth-century drawings of important figures in Seminole history, an early map of Florida, and early depictions of historic cities such as St. Augustine.

The “Florida Landmarks” section showcases views of historic forts, town squares and city parks in a number of cities across the state.

The “Florida Diversions” section features familiar sites such as people enjoying themselves at crowded beaches and at popular destinations such as racetracks, Silver Springs, and the Everglades.

The “Florida Living” section focuses on Florida scenery, domestic architecture and scenes of daily life.

Lastly, the “Florida Impressions” includes lively sketches on paper that were created “on the spot” and represent the artists’ immediate, personal responses to their Florida subjects.

#Vickers Family#samuel vickers#roberta vickers#family#reception#President Kent Fuchs#President Bernie Machen#sam vickers#robbie vickers#the florida legacy#Harn Museum#Harn Museum of Art#gainesville#florida#nature#history#landmarks#diversions#living#impressions#event photography#aaron daye photography

0 notes

Text

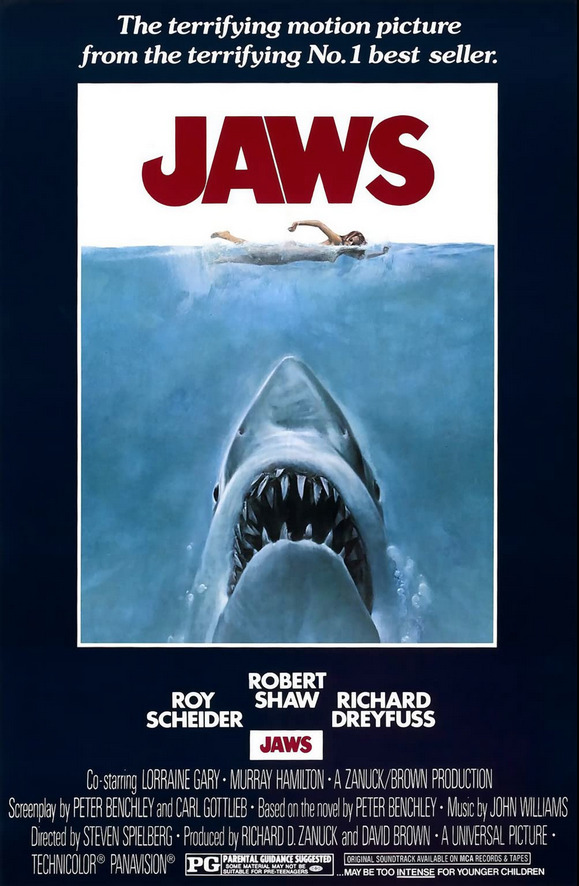

Spielberg Is Sorry

Apparently Steven Spielberg – and Peter Benchley, who wrote the book the movie was based upon – is sorry that Jaws lead to the decimation of the shark population.

Though what I’m wondering is what did they think would happen? Both the film and book spent an inordinate amount of time treating sharks as if they were monsters that would kill us if we didn’t kill them first, when the truth is that…

View On WordPress

#International Shak Attack File#Jaws#Peter Benchley#Steven Spielberg#The Florida Museum of Natural History

0 notes

Text

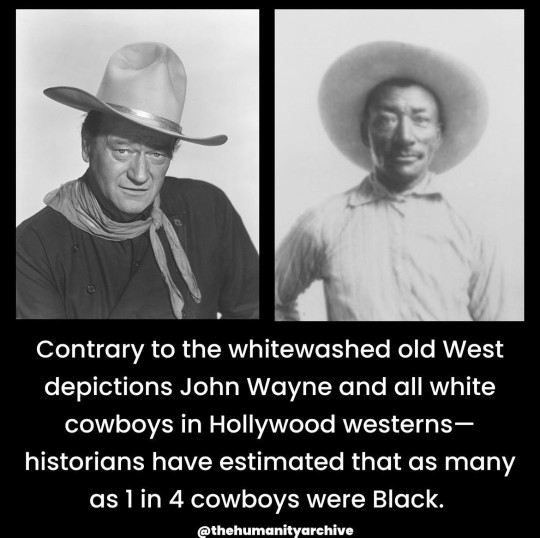

"...the first cowboys lived in Mexico and the Caribbean, and most of them were Black.

That’s the conclusion of a recent analysis of DNA from 400-year-old cow bones excavated on the island of Hispaniola and at sites in Mexico. The work, published in Scientific Reports, also provides evidence that African cattle made it to the Americas at least a century earlier than historians realized.

The timing of these African imports—to the early 1600s—suggests the growth of cattle herds may have been connected to the slave trade, says study author Nicolas Delsol, an archaeozoologist at the Florida Museum of Natural History. “It changes the whole perspective on the mythical figure of the cowboy, which has been whitewashed over the 20th century.”

x

#cowboys#african heritage#caribbean history#mexican history#dna analysis#historical perspective#slave trade#cattle herds#cultural reevaluation#17th century#black cowboys#early americas#black history

305 notes

·

View notes

Text

Animal of the Day!

Titanis (Titanis walleri)

(Photo from Florida Museum of Natural History)

Conservation Status- Extinct

Habitat- North America

Estimated Size (Weight/Length)- 150 kg; 2 m tall

Diet- Mammals

Time Period- Pliocene; Early Pleistocene

Cool Facts- Titanis was one of the larger terror birds that stalked the plains of North America for thousands of years. Incapable of flight, Titanis most likely relied on its long legs to outrun its prey. While a skull has never been found, it is assumed that Titanis had the massive, ax-like beak other terror birds of the time period had, leading to interpretations of what its complete skeleton may look like. Due to having excellent movement in their neck, it is believed that Titanis would chase down its prey and batter the animal to death with its massive beak. Titanis most likely went extinct due to competition from new predators, especially bears and big cats.

Rating- 11/10 (Could outrun a horse.)

#Animal of the day#Animals#Birds#Terror bird#Friday#January 13#Titanis#biology#science#conservation#the more you know#Paleoweek#Paleolithic#Prehistoric#Megafauna#Extinct animals#Paleontology

592 notes

·

View notes

Text

Whales, like wolves, elephants, and beavers, are keystone species, animals who disproportionately shape ecosystems. While alive, their fecal plumes fertilize phytoplankton, the microscopic plants that oxygenate our atmosphere. In death, whales who settle on the ocean floor attract an astonishing necrobiome, the community of scavengers who feed upon the dead: hagfish, mussels, limpets, isopods, sleeper sharks, chemosynthetic bacteria. Some, like bone-eating Osedax worms, subsist exclusively on benthic carcasses. Whalefalls are oases in the abyssal wastes, as enticing to life as a Saharan watering hole. Not every dead whale, however, comes to rest in the depths.

Those whales who drift ashore -- buoyed by internal gasses, conveyed by currents -- support complex ecosystems of their own.

Vultures and seabirds peck at eyes and blowhole; sharks strip blubber in the surf. In Namibia’s coastal deserts, jackals and hyenas gnaw at dead seal pups, dolphins, and whales. When, in 2020, a minke whale -- nicknamed Godfried, for a beloved local author -- washed ashore on a Dutch islet, he was visited by 57 species of beetle, 21 of whom had never been seen on the island before. In Russia, scientists have documented 180 polar bears feasting on a single bowhead.

-------

Once, coastal necrophages could count on a steady supply of whale carcasses. (California’s famously huge grizzlies, now extinct, may have attained their gargantuan size by feeding upon the same marine mammals who supported condors.) Today, however, washed-up cetaceans are comparatively rare. In part, that’s because industrial whaling -- “the largest removal of biomass in world history,” per one researcher -- ravaged the leviathans. Blue whale populations have plummeted by up to 90 percent, and sperm whales endure at just one-third of their historic numbers. Scavengers can’t eat nonexistent animals.

-------

But the dearth of whales isn’t entirely responsible for the dearth of whale carcasses. We humans also tend to be overzealous morticians. Rather than letting stranded animals fulfill their ancient roles, we hastily dispose of their remains, depriving coastal ecosystems of nature’s greatest windfall. As one group of scientists put it in a recent review of cetacean carcass management, whaling and whale-removal have together “led to radical changes in the abundance and availability of large marine biomass inputs.” In other words: Our shorelines miss their whales and dolphins.

Lately, some researchers have begun to pay closer heed to the value of stranded whales, and to encourage coastal managers to let carcasses lie. Granted, not every beach is an appropriate resting place for a reeking, 50,000-pound corpse. When circumstances allow, however, permitting dead whales to decompose in situ may be preferable to disposal. [...]

-------

[E]very country, state, and municipality obeys slightly different protocols. Some whales are carted off to the landfill, incinerator, or rendering plant, where their oily fats may be extracted for soaps, pet foods, and biofuel. Some are towed to sea, weighed down with scrap metal, and sunk. Some are buried. Some are cleaned for museum display. In 1970, the Oregon Highway Department infamously dynamited a gray whale, flattening an Oldsmobile beneath a chunk of flying blubber [...]. Mostly, whales are removed for a prosaic reason: They stink. [...]

As a result, authorities seldom let carcasses lie. Some countries, like Belgium and France, actually require officials to usher dead cetaceans off to a waste-management facility. In the United States, Quaggiotto found that just 28 percent of cetacean carcasses remain in situ -- nearly all of these, surely, on remote beaches in wildlife refuges, national parks, and Alaska. In heavily developed Florida, Megan Stolen, a stranding investigator and scientist with the Blue World Research Institute, estimates that less than 5 percent of dead whales and dolphins get to stay put. [...]

-------

In May 2010, biologists in Alaska’s Glacier Bay National Park spotted a 41-foot-long female humpback carcass sprawled across a beach and, sensing opportunity, set out cameras to monitor her fate.

Over the next four months, brown bears and wolves feasted almost daily, inscribing networks of pawpaths onto forest and beach. The “blubber bonanza” became a site for ursine reproduction -- cameras caught a pair of bears mating -- and even innovation. In July, a researcher observed a young bear scrubbing his muzzle with a barnacle-encrusted rock, like a post-prandial diner dabbing himself with a napkin. [...] “That carcass seemed to be a beacon calling to these huge bears -- and, of course, they got huger and huger,” says Tania Lewis, wildlife biologist at Glacier Bay. “We can never underestimate the importance of the marine ecosystem for the terrestrial ecosystem.”

The Glacier Bay humpback was both a cornucopia and an anachronism, a glimpse of the resplendent necrobiome that predated industrial whaling, coastal development, and aseptic carcass management strategies. The feast lasted until early September, when park staff severed the whale’s head to perform a necropsy. Unmoored, the body lolled into the tide and drifted away; later, it would wash up down the beach, where wolves gnawed the bones. As the whale floated into the sunset, observers on the beach noticed a passenger: a seafaring brown bear, still trying to chisel off a few last morsels of blubber before the bounty bobbed away.

-------

Headline and text by: Ben Goldfarb. “Humans Are Overzealous Whale Morticians.” Nautilus. 10 August 2022.

1K notes

·

View notes

Audio

The song of the now-extinct dusky seaside sparrow.

Taken from the audio cassette tape “Sounds of Florida’s Birds (1998)” by J.W. Hardy, curator emeritus in ornithology and bioacoustics at the Florida Museum of Natural History. [ x ]

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

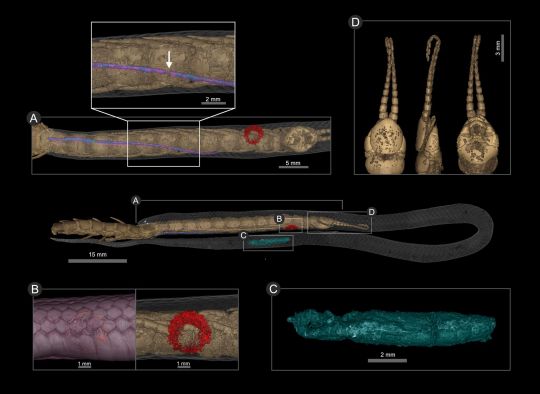

Rare snake found at John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park, that died while eating a large centipede!

The state-threatened rim rock crowned snake (Tantilla oolitica) lives in pine rockland and hammock habitats in eastern Miami-Dade County and the Keys. This burrowing species, typically only 7-9 inches long, is seldom seen because it lives under debris, rocks or in cavities in underlying limestone.

A visitor to the park observed a small, dead snake on a trail with the rear portion of a centipede protruding from its mouth. Other species of crowned snake often eat centipedes, but this specimen represents the first food record of any kind for the little-known rim rock species. Crowned snakes immobilize their prey using mild venom but are unable to bite humans because of their small size. The prey item appears to be a juvenile Keys giant centipede (Scolopendra alternans), which can reach the size of a crowned snake as an adult. Crowned snakes are usually immune to the venom of centipedes, whose bites are painful to humans, but something went wrong during this encounter.

Did the snake choke while trying to consume the centipede? Or did the centipede envenomate and kill the snake?

This bizarre but fortunate discovery gave researchers the opportunity to use diffusible iodine-based contrast-enhanced computed tomography (diceCT) to accurately measure the snake and its prey and determine the cause of death. The diceCT scans indicated a possible obstruction of the compressed trachea, suggesting the snake indeed suffocated while swallowing the hard-bodied prey item.

Close inspection of the CT scans revealed the centipede imparted a parting bite to the snake (red) before being swallowed and blocking the snake's trachea (purple).

This event represented the first dietary record for what may be the rarest snake species in North America! The snake, along with the partially ingested centipede, are now part of the Florida Museum of Natural History collection.

3D model here

[Source: FWC Fish and Wildlife Research Institute - I copy and pasted from their posts, but rearranged it together into one cohesive post]

#rim rock crowned snake#keys giant centipede#pine rockland#florida#florida keys#animal death#snake#centipede

610 notes

·

View notes

Text

A variety of mammal fossils from the Florida Museum of Natural History. Almost all (if not all) of these fossils came from Florida and show how diverse the mammals found in the state have been.

#natural history#paleontology#Florida museum of natural history#museums#sabertooth#extinct rhinoceros#terror bird#short faced bear#horse

155 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Great blue heron

Credit: Florida Museum of Natural History/Photo by Jeff Gage

#jeff gage#photographer#florida museum of natural history#great blue heron#heron#bird photography#nature

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Caecilians are first amphibians shown to pass microbes to their offspring

FLORIDA MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

KOUETE ET AL., 2023

Caecilians are an elusive type of amphibian that primarily live underground and look like a cross between a worm and a snake. One of the few things that is known about caecilians is their unique method for feeding their young. Mothers produce a special layer of fatty skin tissue, which juvenile caecilians tear off with baby teeth that evolved specifically for that purpose.

A new study shows that skin-feeding does more than provide nutrients for young caecilians.

It also helps the mother pass microbes from her skin and gut down to her young, inoculating them to jump-start a healthy microbiome. This is the first direct evidence that parental care in an amphibian plays a role in passing microbes from one generation to the next...

Read more: https://www.eurekalert.org/news-releases/996426

image: Herpele squalostoma, from central Africa

94 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Dress

Ann Lowe, 1960s

Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture

Green means nature.

Central Florida Emergency Trans Care Fund

Equality Florida

ACLU Florida

Tampa Bay Abortion Fund

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm subscribed to the Florida Museum of Natural History's newsletter, and a link to this article was included in the most recent one. It talks about the natural features of Florida, and I really enjoyed it--not just because I like nature, but because it's nice to see something positive about my home for once.

Florida is an endlessly beautiful place, full of endlessly wonderful people, and we're all being held hostage by our shitty, cruel, increasingly-fascist state government. But god damn it, there are things here worth loving.

From the article:

Even though Florida is relatively young geologically-speaking, the state has a rich geologic history going back millions of years. As we face sea level rise, increased global temperatures, and increased extreme weather events from human-caused climate change, understanding how Florida has responded to such conditions in the past is the key to understanding our future.

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lady Cust's Great Auk egg

An Egg of the Extinct Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis), Iceland, 1844

Eggs of the Great Auk are regarded as being among the most sought-after of all natural history objects, due to their exceptional rarity. The Victorians thought of them so highly that every surviving egg was listed and its whereabouts carefully recorded. At this time more than 60 had survived and each of these had been collected in the years before 1844, when the bird itself became extinct.Today, almost all of those that still exist are in museums from which they will never be released with only four remaining in private hands.

The Great Auk was a flightless, aquatic bird measuring approximately 2½ feet tall and weighing on average 11 pounds. With a black body and white underbelly, its appearance fell somewhere between a puffin and a penguin. When hunting, the Great Auk employed a hooked beak and powerful swimming stroke to stalk fish and crustaceans. Native to the cold waters of the North Atlantic, their nesting areas ranged from the coasts of Newfoundland, Maine, Massachusetts, and even South Carolina and Florida, to Iceland, the Faroe Islands, the eastern coast of Greenland, and the islands off the coast of Scotland, namely the Orkneys and St Kilda; during the winter months they were known to go as far west as Norway and Denmark, and skeletal remains have been found as far south as Gibraltar.

Great Auk pairs mated for life, laying but one egg per breeding season on small islands and rocky coastlines. The longitudinal, pear-shaped eggs were perfectly adapted to roll in tight circles, greatly reducing the chance of being lost off a cliff edge. Parents would take turns incubating the egg, all while benefitting from the protection of dense social colonies and few natural predators.

Historical records indicate that the Great Auk showed no innate fear of humans, and this—coupled with their slow and awkward movements on land—greatly increased their vulnerability to extinction as Europeans began to massively exploit the species for food, for their downy feathers, and horrifyingly, for kindling in fires, as their very oily feathers were highly flammable.

On June 3, 1844, the last known breeding pair of Great Auks were killed off the coast of Iceland, on Eldey Island, after being captured by fisherman, making this incredibly rare specimen a poignant reminder of humanity's responsibility to conservation and environmental stewardship.

Because of their tragic history, Great Auk eggs are exceedingly rare, and even more so in private hands. Thanks to the efforts of early passionate ornithologists, in particular Symington Grieve, Edward Bidwell, Paule Marie Louise & John Whitaker Tomkinson, Ch. F. Dubois, and Leon Olpho-Galliard, surviving specimens of skins and eggs, including the present example, are well-documented in the literature.

The first record of Lady Cust’s Egg is that it was bought in Paris during the first half of the nineteenth century by the celebrated naturalist William Yarrell who presented it to Lady Cust. No-one knows quite why he did this, but she kept it for many years. At her death it passed into the collection of another well-known ornithologist, George Dawson Rowley, and it has passed through the collections of several other illustrious naturalists (including Captain Vivian Hewitt) in the years since his time.

The egg is listed and its story told in Symington Grieve’s celebrated monograph The Great Auk (1888), P. and J., Tomkinson’s Eggs of the Great Auk (1966) and Errol Fuller’s comprehensive book The Great Auk (1999).

Top right photo: LADY CUST’S EGG ILLUSTRATED IN TOMKINSON'S CELEBRATED TREATISE EGGS OF THE GREAT AUK (PUBLISHED IN 1966, BUT THE PHOTOS TAKEN CIRCA 1900).

Sotheby’s

174 notes

·

View notes