#Greil Marcus

Text

Happy 78th, Greil Marcus.

Photo by Michael Goldberg.

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

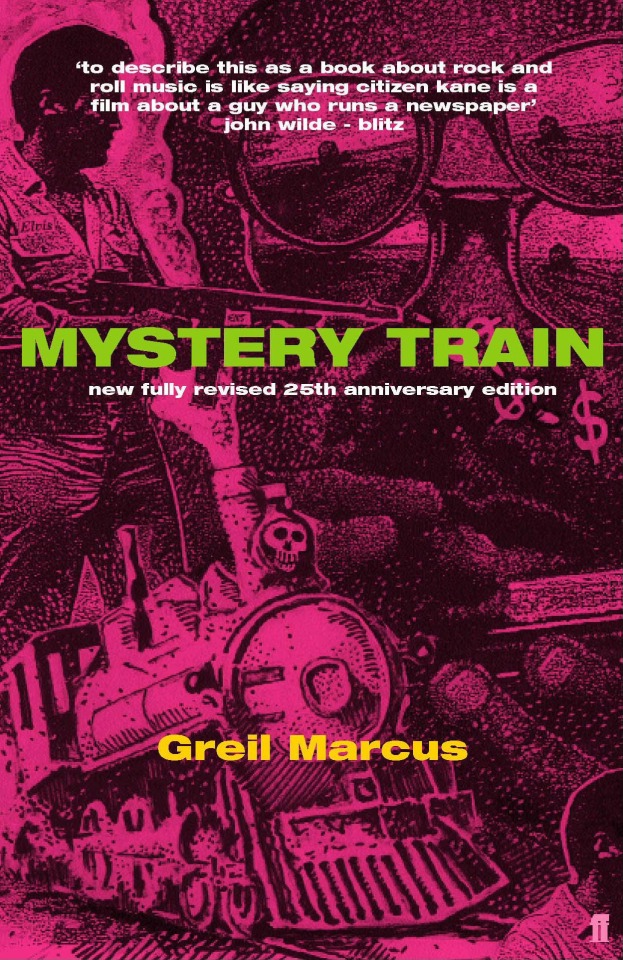

He had to learn, in John Barth’s line, that the key to the treasure is the treasure—that to be free is not to get what you want... but to begin to know what you want and to feel strong enough to go after it... For a moment, to say yes is to say everything. - Mystery Train: Images of America in Rock ‘n’ Roll Music

by Greil Marcus

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

With anyone else but Mary Weiss as a lead singer, the doom in Shangri-Las songs might have turned into a joke, but it never happened: every time, whether in “Remember,” “Give Us Your Blessings,” “Out in the Streets,” “I Can Never Go Home Anymore,” or “Past, Present, and Future,” the singer was a different person, starting from the beginning, telling her story as far as it would go, which was never very far. Their songs, like Winehouse’s, were all locked doors, doors that locked you out or that you locked yourself from the inside.

Greil Marcus

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

J.T. Walsh (1999)

I like Oliver Stone movies, but I stayed away from his Nixon when it was in the theaters in 1995, and never rented it on video. As the child of good California Democrats, I grew up hating Nixon. When I was in my twenties and he was president, he gave me more reason to hate him than I ever wanted. When he died I didn’t want to think about him anymore.

One night, though, flipping channels after the late news had closed down, I happened onto Nixon running on HBO, and I didn’t turn it off. I was pulled in, played like a fish through all the fictions and flashbacks, dreaming the movie’s dream: waiting for Watergate.

It came into focus with a strategy session in the Oval Office. Anthony Hopkins’s Nixon is hunching his shoulders and looking for help. James Woods’s impossibly reptilian H. R. Haldeman is stamping his feet like Rumpelstiltskin and fulminating about “Jew York City.” Others raise their voices here and there—and off to the side is J. T. Walsh, the canniest and most invisible actor of the 1990s, doodling.

As almost always, Walsh was playing a sleaze, a masked thug, here a corrupt government official, White House adviser and Watergate conspirator John Ehrlichman—as elsewhere he has played a slick Hollywood producer, a college-basketball fixer, the head of a crew of aluminum siding salesmen, a porn king who makes home sex videos with his own daughter, a slew of cops (Internal Affairs bureaucrat on the take in Chicago, leader of a secret society of white fascists in the LAPD), and a whole gallery of con artists, confidence men who seem to live less to take your money than for the satisfaction of getting you to trust them first.

Walsh in the Oval Office is physically indistinct; he usually was. At fifty-two in 1995 he looked younger, just as he looked older than his age when, after eight years as a stage actor—most notably as the frothing sales boss in David Mamet’s Glengarry Glen Ross—he began getting movie roles in 1986. Except near the end of his life, when his weight went badly out of control, his characters would have been hard to pick out of a lineup. Like Bill Clinton he was fleshy, vaguely overweight, with an open, florid, unlined face, a manner of surpassing reasonableness, blond in a way that on a beige couch would all but let him fade into the cushions. He had nothing in common with even the cooler, more sarcastic heavies of the forties or the fifties—Victor Buono’s police chief in To Have and Have Not, say, or the coroner in Kiss Me Deadly, their words dripping from their mouths like syrup with flies in it. He had nothing to say to the heavies appearing alongside of him in the multiplexes—Dennis Hopper’s psychokillers, Robert Dalvi’s scum-suckers, Mickey Rourke, with slime oozing through his pores, the undead Christopher Walken, his soul cannibalized long ago, nothing left but a waxy shell.

Walsh’s characters are extreme only on the inside, if he allows you to believe they are extreme at all; as he moves through a film, regardless of how much or how little formal authority his character might wield, Walsh is ordinary. You’ve seen this guy a million times. You’ll see him for the rest of your life. “What I enjoy most as an actor,” he said in December 1997, two months before his death from a heart attack, “is just disappearing. Most bad people I’ve known in my life have been transparent. Not gaunt expressions—they’re Milquetoasts. It’s Jeffrey Dahmer arguing with cops in the streets about a kid he’s about to eat—and he convinces them to let him keep him. And takes him back up and eats him. What is the nature of evil that we get so fascinated by it? It’s buried in charm, it’s not buried in horror.”

Walsh’s charm—what made you believe him, whether you were another character standing next to him in a two-shot, or watching in the audience—was a disarming, everyday realism, often contrived in small, edge-of-the-plot roles, his work with a single expression or a line staying with you long after any memory of the plot crumbled. As a lawyer happily tossing Linda Fiorentino criminal advice while an American flag waves in the breeze outside his window, Walsh taps into a profane quickness that for the few moments he’s on-screen dissolves the all-atmosphere-all-the-time film noir gloom of John Dahl’s The Last Seduction. In The Grifters, as Cole Langley, master of the long con, he radiates an all-American salesman’s glee (“Laws will be broken!” he promises a mark) that makes the hustlers holding the screen in the film—Anjelica Huston, John Cusack, Annette Bening—seem like literary conceits. Yet it all comes through a haze of blandness, as it does even when Walsh plays a sex killer, a crime boss, a rapist, a racist murderer, as if at any moment any terrible impression can be smoothed away: How could you imagine that’s what I meant?

In the Oval Office his Ehrlichman, whom America would encounter as the snarling pit bull lashing back at Senator Sam Ervin’s Watergate investigations committee, retains only the blandness, occasionally offering no more than “I don’t know if that’s such a good idea” before returning to his doodles. It was this blandness that allowed Walsh to flit through history—in Nixon playing White House fixer Ehrlichman; in Hoffa Teamster president Frank Fitzsimmons, locked into power by a deal that Ehrlichman helped broker; in Wired reporter Bob Woodward, who helped bring Ehrlichman down—but as Walsh sits with Nixon and Haldeman and the rest you can imagine him absenting himself from the action as it happens, instead contemplating all the roles in all the movies that have brought him to the point where he can take part in a plot to con an entire nation.

What makes Walsh such an uncanny presence on-screen—to the degree that, as the trucker in the first scenes of Breakdown, or Fitzsimmons as a drunken Teamster yes-man early in Hoffa, he seems to fade off the screen and out of the movie, back into everyday life—is that while the blandness of his characters may be a disguise, it can be far more believable than whatever evil it is apparently meant to hide. Even as it is committed, the evil act of a Walsh character can seem unreal, a trick to be taken back at the last moment, even long after that moment has passed—and that is because his characters, the real people he is playing, can appear to have no true identity at all. You can’t pick them out of the lineups of their own lives.

At the very beginning of his film career, in 1987, in David Mamet’s House of Games, Walsh is the dumb businessman victim of a gang of con men running a bait-and-switch, then a cop setting them up for a bust, then a dead cop, then one of the con men himself, alive and complaining, “Why do I always have to play the straight man?” The straight man? you ask him back. In Breakdown, in a rare role in which he dominates a film from beginning to end, he first appears as a gruffly helpful trucker giving a woman a ride into town while her husband waits with their broken-down car. She disappears, and when the husband finally confronts the trucker, with a cop at his side, Walsh’s irritated denial that he’s ever seen his man before in his life seems perfectly justifiable—even if, as Walsh saw it, that scene “had a residual effect on the audience. ‘Don’t catch me acting’—when I lied, deadpan, on the road, you hear people in the audience: ‘He’s lying!'”The moment came loose from the plot, as if, Walsh said, “I’m not just acting”—and that, he said, was where all the cheers in the theaters came from when in the final scene he dies. He had fooled the audience as much as the other characters in the movie; that’s why the audience wanted him dead.

Walsh’s richest role came in John Dahl’s Red Rock West. The mistaken-identity plot—with good guy Nicolas Cage mistaken for hit man Dennis Hopper—centers on Walsh’s Wayne Brown, a Wyoming bar owner who’s hired one Lyle from Texas to murder his wife. As Brown, Walsh is also the Red Rock sheriff—and he is also Kevin McCord, a former steelworks bookkeeper from Illinois who along with his wife stole $1.9 million and was last seen on the Ten Most Wanted list. Walsh plays every role—or every self—with a kind of terrorized assurance that breaks out as calm, certain reason or calm, reasoned rage. He’s cool, efficient, panicky, dazed, quick, confused. You realize his character no longer has any idea who he is, and that he doesn’t care—and that it’s in the fact that they don’t care that the real terror of Walsh’s characters resides. You realize, too, watching this movie, that in all of his best roles Walsh is a center of nervous gravity. His acting, its subject, is all about absolute certainty in the face of utter doubt. Yes, you’re fooled, and the characters around Walsh’s might be; you can’t tell if Walsh’s character is fooled or not.

At the final facedown in Red Rock West, all the characters are assembled and Dennis Hopper’s Lyle is holding the gun. “Hey, Wayne, let me ask you something,” he says. “How’d you ever get to be sheriff?” “I was elected,” Walsh says with pride. “Yeah, he bought every voter in the county a drink,” his wife sneers—but so what? Isn’t that the American way? Get Walsh out of ‘this fix and it wouldn’t have been the last election he won.

Watching this odd, deadly scene in 1998, I thought of Bill Clinton again, as of course one never would have in 1992, when Red Rock West was released and Clinton was someone the country had yet to really meet. In the moment, looking back, seeing a face and a demeanor coming together out of bits and pieces of films made over the last dozen years, it was as if—in the blandness, the disarming charm, the inscrutability, the menace, the blondness, moving with big, careful gestures inside a haze of sincerity—Walsh had been playing Clinton all along. He was not, but the spirit of the times finds its own vessels, and, really, the feeling was far more queer: it was as if, all along, Bill Clinton had been playing J. T. Walsh.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

That paragraph in Greil Marcus’s Lipstick Traces where he reimagines Theodor Adorno’s book Minima Moralia as a spoken-word LP entitled Big Ted Says No.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

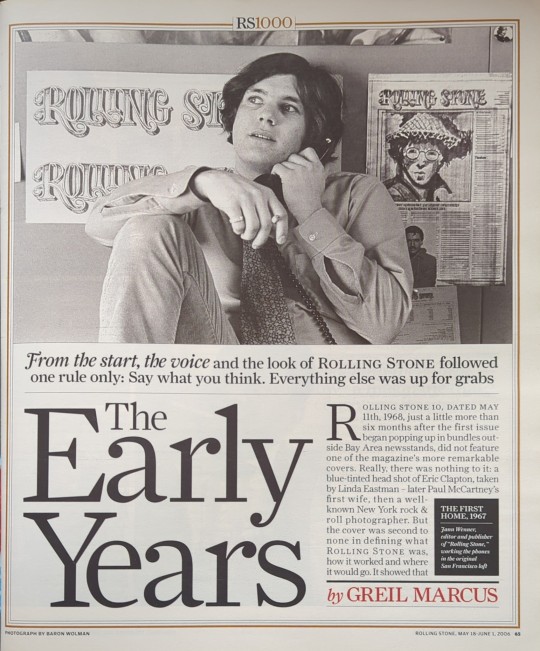

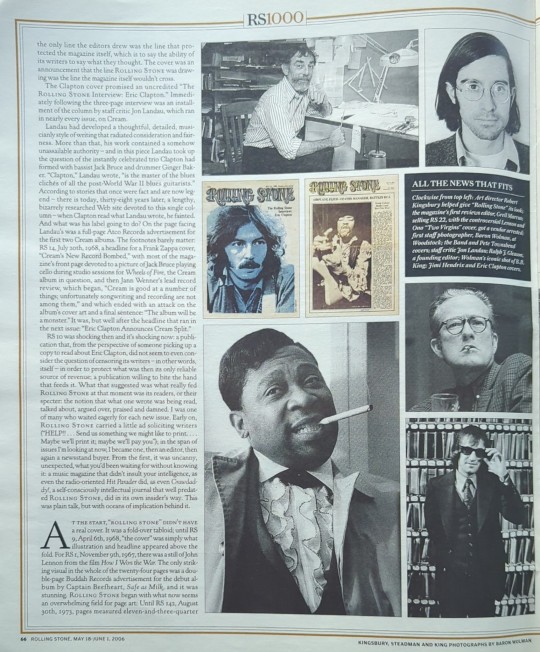

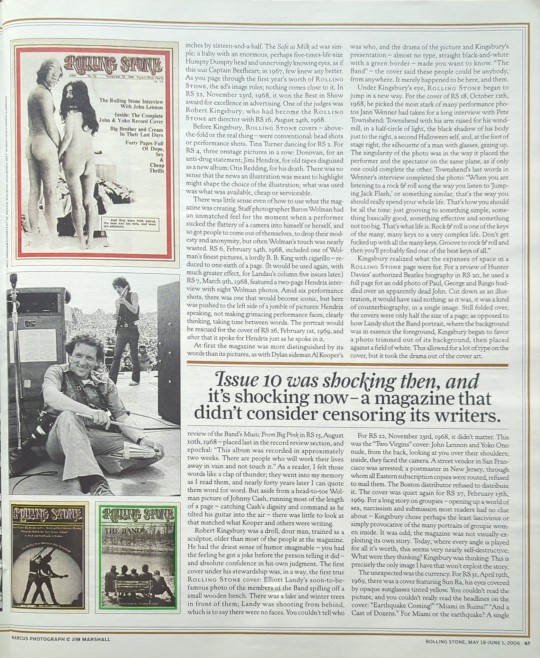

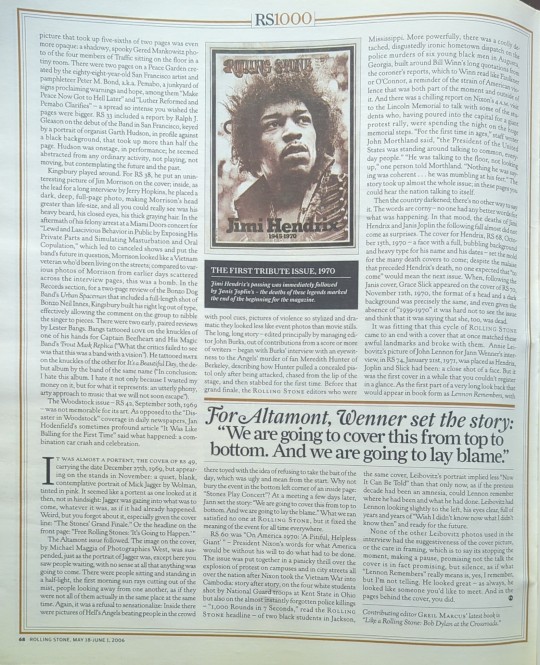

#rolling stone magazine#rolling stone#1000th issue#jann wenner#robert kingsbury#greil marcus#baron wolman#jon landau#ralph j. gleason

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

New books: Essay in Bob Dylan: Mixing Up the Medicine, mentions in books by Jesse Rifkin and Sasha Frere-Jones

The new 600-page catalog of the Bob Dylan Archive in Tulsa, titled Bob Dylan: Mixing Up the Medicine, contains an essay by me about Dylan's relationship to improvisation, inspired by an outtake from the 1976 Hard Rain TV special of "Tangled Up in Blue." In addition to scads of illustrations of the archive's holding, the book also has essays from Lee Ranaldo, Richard Hell, Ed Ruscha, John Doe, Greg Tate, Alex Ross, Greil Marcus, Lucy Sante, Michael Ondaatje, Clinton Heylin, and many others. Much appreciation to editor Mark Davidson, and to Michael Chaiken, who commissioned the piece and brought me to Tulsa to spend time at the archive. More info here.

In other book news, I was interviewed fairly extensively about working at Tonic, the now-defunct Lower East Side music club, by Jesse Rifkin for his book This Must Be the Place: Music, Community, and Vanished Spaces in New York City. And my friend Sasha Frere-Jones has some nice things to say about a short-lived band we had together in the late 90s in his memoir, Earlier.

#bob dylan#bobdylancenter#leeranaldo#richard hell#ed ruscha#greg tate#Greil Marcus#Lucy sante#michael ondaatje#clinton heylin#Jesse rifkin#Sasha frère-jones

2 notes

·

View notes

Quote

As a musician, Cat Power hears songs differently: differently from the person or persons who made them, differently from you, differently from me, and given time and place differently from herself: “Unhate,” the most constructed and alluring number here, is a remake of her own “Hate.” Sometimes she can’t, or doesn’t try to, get out from under the basic arrangement of a tune, as if it’s as fixed as its title: “These Days,” “It Wasn’t God Who Made Honky Tonk Angels.” But I’ve heard Bob Seger’s “Against the Wind” hundreds of times over more than 40 years. I used to think it was a clichéd 'Oh poor me I’m a star now' song with easy listening music; now I hear it as something that can imprint every element of itself in your memory and on your skin and make you examine your values. I’ve listened to Cat Power do a song called “Against the Wind” over and over: in the sound she creates, instruments and voice, this is a song about wind. It says, “AGAINST THE WIND by Bob Seger,” right inside the CD, and I’m still not convinced that it is.

Greil Marcus on Cat Power’s Covers album

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Source: lisamarie-vee

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

This sucks. It's hard enough to try keep a recording studio afloat without any robberies. Been a longtime John Vanderslice fan, and recently both his new music and interviews—like the one he did on The Best Show With Tom Scharpling a few weeks ago—have been truly inspiring and represent a new level of honesty and freedom on his part. I can't wait to see him live this Sunday night in Boston. Kick in a few bucks to this studio recovery fund if you can and wanna!

p.s. I had a very memorable day at this very studio. I was on the west coast leg of the AW68 book tour and legendary music writer Greil Marcus had gotten in touch wanting to know more about the lost Van Morrison Boston 1968 recording I wrote about in the book. This was before Van himself leaked it to the internet. So, I said, "Greil, you absolutely should and deserve to hear this. Let's meet up." At first the idea of a coffee shop was thrown around. I thought to myself, "Greil's gotta hear this loud and on good speakers." So, I shoot an email to John Vanderslice, asking if Greil Marcus and I could sit at Tiny Telephone and listen an ultra-rare Van Morrison bootleg super loud and within minutes he replied and was like, "100% yes." He was an amazing, larger-than-life host who didn't charge us a nickel for the use of the studio that day. That's what kind of guy JV is. Support your weirdo lifers dedicated to ideas and art, my friends!

Photo Caption: Did you have to put my meager donation right next to Jack White's, GoFundMe? Did ya?

1 note

·

View note

Photo

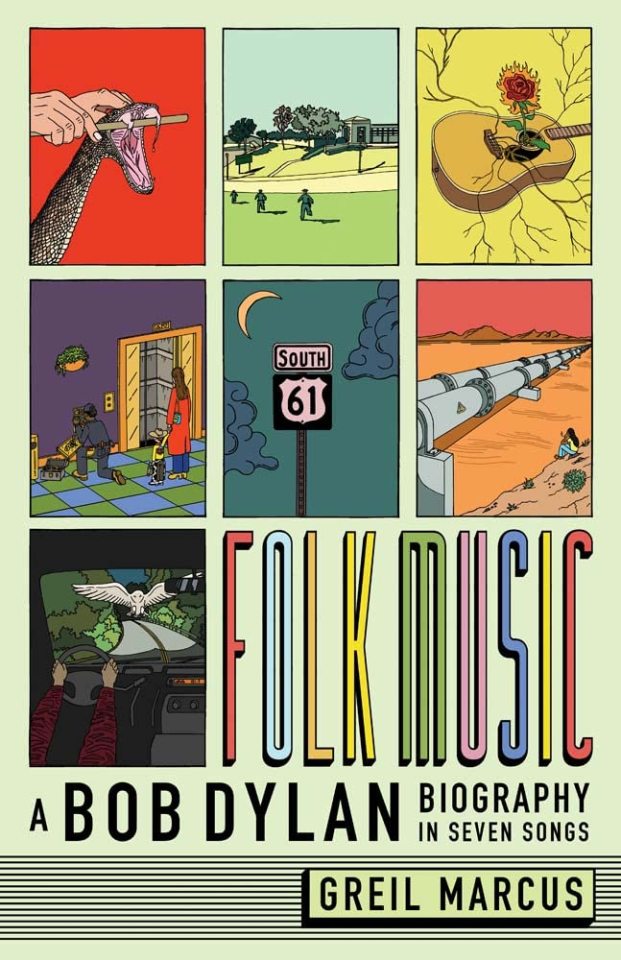

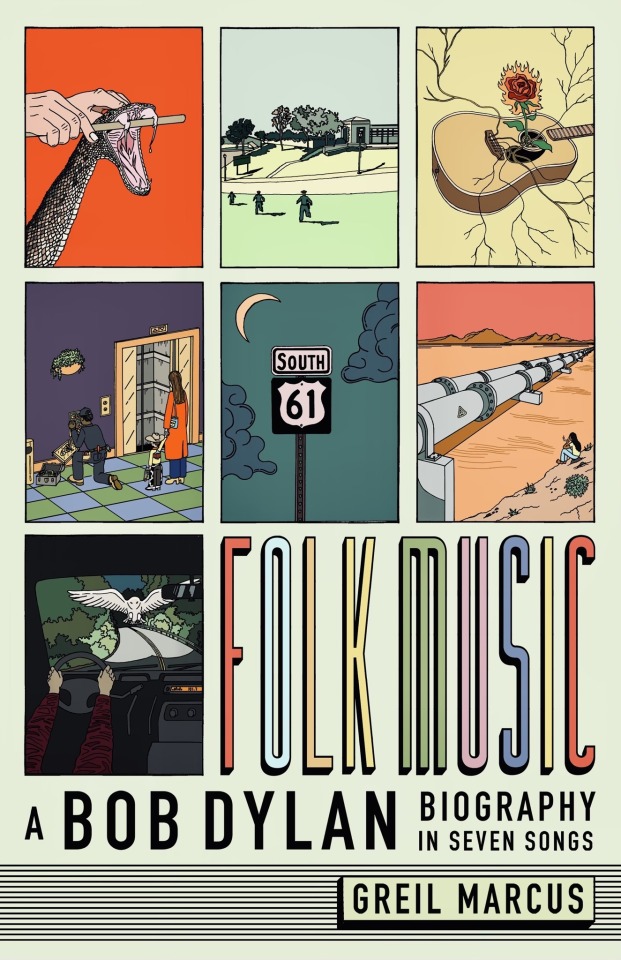

Folk Music: A Bob Dylan Biography in Seven Songs

By Greil Marcus.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

All of Eric Clapton’s love for Johnson’s music came to bear not when Clapton sang Johnson’s songs, but when, once Johnson’s music became part of who Clapton was, Clapton came closest to himself: in the passion of “Layla” and “Any Day.” Finally, after years of practice and imitation, Johnson’s sound was Clapton’s sound: there was no way to separate the two men, nor any need to. -

Mystery Train: Images of America in Rock 'n' Roll Music

by Greil Marcus

1 note

·

View note

Text

instagram

1 note

·

View note

Text

no idea if this is true or not but I want to believe

1 note

·

View note

Photo

18 notes

·

View notes