#Hongshan culture

Text

Jade Hooked Cloud-shaped Pei Ornament [China, Late Hongshan Culture (3500-3000 B.C.)]

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spotlight Art – History – Pig-dragon Pendant – Hongshan Culture – Niuheliang - Jianping -China

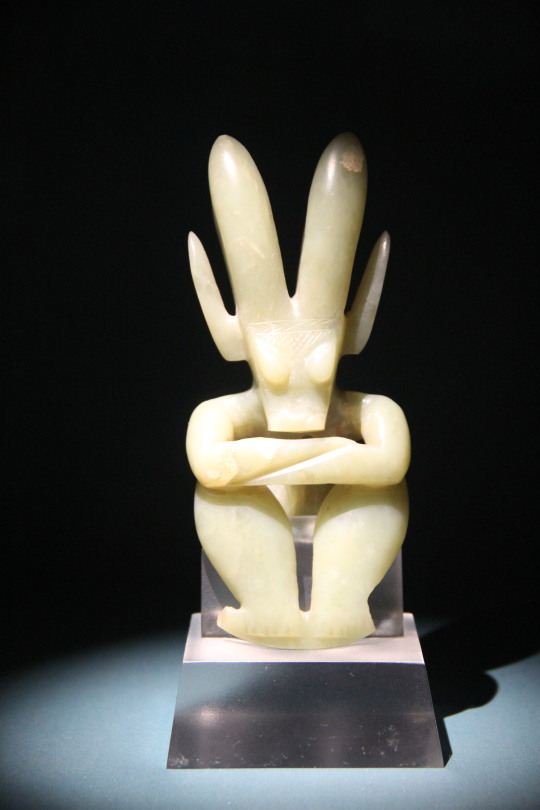

Pig-dragon Pendant

The translucent, smooth polished, jade of a pale celadon tone Pig-dragon Pendant (H 10.3cm from Tomb 4 at Niuheliang, near Jianping, Liaoning Province, Northeast China; and, is from the Neolithic Hongshan Culture that dates from c. 4200 BCE – 2900 BCE – Liaoning Provincial Institute of Archaeology, Shenyang.

The coiled pendant came from a the tomb of an apparently important…

View On WordPress

#Art#Art Music Photography Poetry Quotations#China#Goff James#Goff James Art Music Photography Poetry Quotations#goffjamesart#History#Hongshan Culture#Jianping#Niuheliang#Photograph#Pig-dragon Pendant#Poem#Poet#Poetry#Senryū

0 notes

Text

[Hanfu · 漢服]China's national Important Cultural Relics Impression Series By Artist @陆曼陀

China Neolithic Period:The Hongshan culture(4700-2900 BC)Relics<玉猪龙/Pig dragon>

China Shang dynasty / Western Zhou dynasty(1200–800 BC) · Shu state Relics < 太阳神鸟金饰/Golden Sun Bird>

China Western Han Dynasty (202 BC – 9 AD)Artifact Relics<长信宫灯/oil lamp in the shape of a kneeling female servant>

After the lamp is lit, the soot enters the base of the palace lantern through the sleeve to achieve the purpose of cleaning the air.

China Eastern Han Dynasty(25–220 AD)Artifact Relics<铜奔马 or the Galloping Horse Treading on a Flying Swallow (馬踏飛燕)>

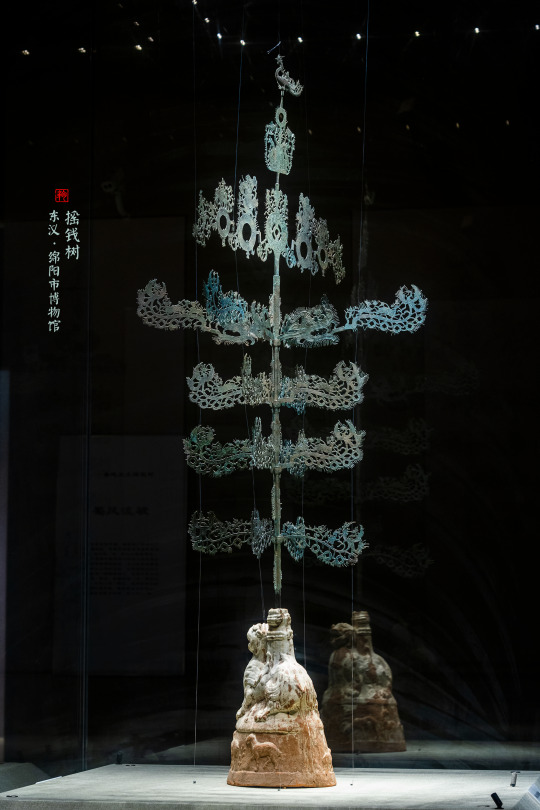

China Eastern Han Dynasty(25–220 AD) Artifact Relics<摇钱树/Money tree (myth)>

China Tang Dynasty(618–907CE) Artifact Relics<女立俑/Female standing figurine >

China Song Dynasty (960–1279) Artifact Relics<汝窑天蓝釉刻花鹅颈瓶/Ru kiln sky blue glaze carved gooseneck bottle>

China Song Dynasty (960–1279) Painting<千里江山图/A Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains>by 王希孟(Wang Ximeng)

China Yuan dynasty (1279–1368) Artifact Relics<霁蓝釉白龙纹梅瓶/Ji blue-glazed plum vase with white dragon pattern>

【Artist:陆曼陀 Social Media】

————————

Twitter:https://twitter.com/LuDanling

Weibo:https://weibo.com/u/2846691957

Post Source:https://weibo.com/2846691957/NzQ9IyzKL

————————

#chinese hanfu#陆曼陀#China history#chinese art#hanfu illustration#hanfu accessories#hanfu#hanfu history#china#chinese#history#chinese aesthetics#culture relic#汉服#漢服#heritage#civilization

426 notes

·

View notes

Text

A yellow jade owl, probably Neolithic period, Hongshan culture (c. 3800-2700 BC)

Courtesy Alain Truong

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Neolithic Hongshan Culture 4700 to 2900 BCE

I'm just going to do a summary post on all these Hongshan artworks here. Hongshan seems to have artwork depicting both Caucasoid and Mongoloid people. One of them has large, deep-set blue jade eyes and doesn't look anything like modern day Chinese people. However, there are also a lot of figures that do look like modern day Chinese people. It would seem there was a variety of different people living in the area. There are also a large variety of depictions of dragons and what appear to be dragon-human hybrids, as well as dragon embryos. Some statues appear to show mating between humans and dragons or other creatures. It's possible these statues tell stories of humans claiming to be descended from dragons. See my other Hongshan post (Dragon of the Hongshan Culture 4500-3000 BCE) for more info on genetic curiosities.

More images on my blog: https://paganimagevault.blogspot.com/2023/08/neolithic-hongshan-culture-4700-to-2900.html

#chinese history#dragons#ancient history#history#anthropology#art#statue#ancient art#archaeology#neolithic

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jade pectoral mask, Hongshan culture (Neolithic China), 3500 - 3000 BC

from Artemis Gallery

590 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Hongshan underground Goddess Temple housed beautiful and mysterious relics of unknown deities, and larger-than-life statues. Uncovered in 1983, the sprawling archaeological dig at Niuheliang has revealed ritual sites, stone circles, and graves filled with jade artifacts.

28 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jade pectoral mask, Hongshan culture (Neolithic China), 3500 3000 BC

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

This Lunar New Year Is the Year of the Dragon: Why the Beast Is a Big Deal in Chinese Culture

— By Chad De Guzman | Wednesday February 6, 2024 | Time Magazine

A traditional Chinese New Year dragon dance is performed in Liverpool’s Chinatown in January 2023.Getty Images

The last time China’s birth rates peaked was in 2012: that year, for every 1,000 people, there were 15 live births, a far cry from 2023’s 6.39. It was a statistical anomaly, considering the country’s ongoing state of demographic decline, which has proven extremely difficult to reverse. But 2024 may just see another baby boom for China, for the same reason as 12 years ago: it’s a Year of the Dragon.

Dragons are a big deal in Chinese culture. Whereas in the West dragons are often depicted as winged, fire-breathing monsters, the Chinese dragon, or the loong, is a symbol of strength and magnanimity. The mythical being is so revered that it snagged a spot as the only fictional creature in the Chinese Zodiac’s divine roster. And the imagery pervades society today—whether in boats, dances, or the stars.

International discourse about China’s economy or politics also often references the country as a “red dragon,” which critics have said subconsciously panders to Orientalism and fears of communism. But many Chinese proudly embrace the connection: China’s President Xi Jinping told former President Donald Trump in 2017 that the Chinese people are black-haired, yellow-skinned “descendants of the dragon.”

That’s why, in Years of the Dragon (which happen every 12 years), spikes in births tend to occur in China (as well as other countries with large Chinese populations, such as Singapore), as many aspiring parents try to time their pregnancies to result in a child born with the beast’s positive superstitious associations.

A Symbol of Prosperity

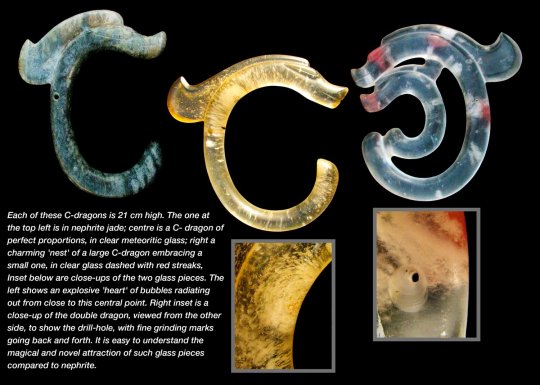

Where the Chinese dragon first came from is still debated by historians and archaeologists. But one of the most ancient images of the loong was unearthed in a tomb in 1987 in Puyang, Henan: a two-meter-long statue dating back to the Neolithic civilization of Yangshao Culture some 5,000–7,500 years ago. Meanwhile, Hongshan Culture’s Jade Dragon—a C-shaped carving with a snout, mane, and thin eyes—could be traced back to Inner Mongolia five millennia back.

Marco Meccarelli, an art historian at the University of Macerata in Italy, writes that there are four reliable theories for how the loong came to be: first, a deified snake whose anatomy is a collage of other worldly animals (based upon how, as ancient Chinese tribes merged, so did the animal totems that represent them); second, a callback to the Chinese alligator; third, a reference to thunder and a harbinger of rain; and lastly, as a by-product of nature worship.

Most of these theories point to the dragon’s supposed influence on water, because they are believed to be gods of the element, and thus, agricultural numen for a bountiful harvest. Some academics have said that across regions, ancient Chinese groups continued to enrich the dragon image with features of animals most familiar to them—for example, those living near the Liaohe River in northeast China integrated the hog into the dragon image, while people in central China added the cow, and up north where Shanxi is now, earlier residents mixed the dragon’s features with those of the snake.

A Symbol of Power

Nothing cemented the Chinese dragon’s might better than when it became a symbol of the empire. The mythical Yellow Emperor, a legendary sovereign, is said to have been fetched by a Chinese dragon to head to the afterlife. The loong are also said to have literally fathered emperors, or at least that’s what Liu Bang, the first emperor of the Han dynasty (202-195 B.C.), made his subjects believe: that he was born after his mother consorted with a Chinese dragon.

“The dragon totem and its corresponding clout were employed as a political tool for wielding power in imperial China,” Xiaohuan Zhao, associate professor of Chinese literary and theater Studies at the University of Sydney, tells TIME.

From then on, the loong was a recurrent theme across dynasties. The seat of the emperor was called the Dragon Throne, and every emperor was called “the true Dragon as the Son of Heaven.” D. C. Zhang, a researcher in the Institute of Oriental Studies at the Slovak Academy of Sciences in Bratislava, tells TIME that later dynasties even prohibited commoners from using any Chinese dragon motif on their clothes if they weren’t part of the imperial family.

The Qing Dynasty (1644-1912) created the first iteration of a Chinese national flag featuring a dragon with a red pearl, which was to be hung on Navy ships. But as the Qing Dynasty weakened after several notable military losses, including the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895) and Boxer Rebellion of 1900, caricatures of the dragon began to be used as a form to protest against the government for its weakness, says Zhang. But with the dynasty’s fall after the establishment of the Republic of China (ROC)—which would then become Taiwan—in 1912, Zhang says the pursuit of a national emblem was temporarily cast aside.

During the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945), there had been renewed calls to find a unifying symbol to boost morale, and the dragon was among several animals considered. But when Mao Zedong established the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949, the quest for a unifying symbol for the Chinese was forgotten again, as the country pivoted priorities toward rapid industrial development.

A Symbol of Unity

Outside China, the dragon motif may have quickly caught on, but inside it, the dragon was not as influential until the 1980s, says Zhang. In 1978, Taiwanese musician Hou Dejian composed a song entitled “Heirs of the Dragon” as a means to express frustration over the U.S.’s decision to recognize the PRC as China’s legitimate government and sever diplomatic ties with the ROC (Taiwan). Lee Chien-fu, a Taiwanese student at the time, released a cover of the song in 1980 that grew immensely popular on the island.

Despite being a song decrying Taiwan’s disappointment, the song managed to cross the strait and also resonated with citizens of the mainland. Zhang says “China was becoming stronger” and its government tried to co-opt “Heirs of the Dragon” as it needed an emblem for unification and prosperity “which would be apolitical and would be inclusive to all Chinese nations even for those living abroad.” Hou, who had since moved to China, sang the song in a Chinese state variety show to usher in the Year of the Dragon in 1988.

But the song’s popularity also led it to be used against the Chinese leadership. Dissidents turned “Heirs of the Dragon” back into a protest anthem before the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown, according to the South China Morning Post, with Hou even changing some of the lyrics according to Zhang. Hou was deported back to Taiwan in 1990, but his music stayed with the ethnically Chinese and the Chinese diaspora, Zhang says.

The song as well as China’s overt efforts to create a national symbol that transcends borders, Zhang says, play a large part in the lasting cultural significance of the loong. And the dragon’s historic regality has certainly helped boost the mythos, symbolism, and popular sentimental attachment for Chinese people today, says University of Sydney’s Zhao. “The basic characteristics, features, beliefs and practices associated with dragon totem and clout remain largely unchanged,” he says. “It’s very much a living tradition.”

#China 🇨🇳#Chinese Culture#Chinese Symbolism#Chinese Dragon 🐉 Symbolism#Lunar Year#Year of Dragon 🐉#Beast#Big Deal#Chad De Guzman#Time Magazine#Chinatown#Symbol of Prosperity | Power | Unity

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

VERY RARE CHINESE YELLOW JADE ARCHAIC SCEPTER NEOLITHIC PERIOD HONGSHAN CULTURE ebay Joanies Fine Estate Treasures

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

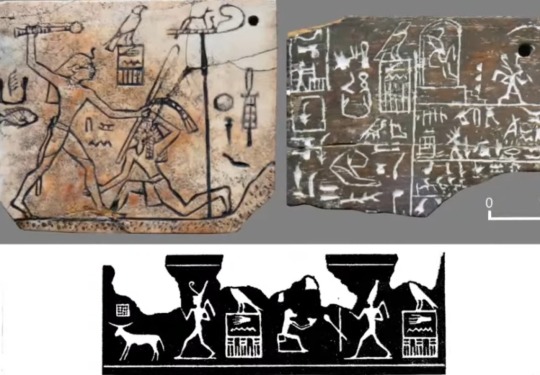

Ancient Egypt was nuts.

This is Predynastic Egyptian art. This predates the creation of hieroglyphics. This is like 3000 BC. And they had already developed the sophisticated, standardized ideogram forms they would continue to use until almost 400 AD.

These people were only 1000 years removed from being hunter-gatherers who used stone arrowheads and lived in caves when they came up with this art. And it remained a recognizable cultural hallmark for them until the fall of Rome. That is nearly 3500 years of people putting the same skirt and same crown on the same guy, who is hitting another guy with the same mace, to say "I got those bastards good."

This is from the Ptolematic Era, during which horribly inbred Macedonian Greeks ruled Egypt, Game-of-Thrones style, until the Romans got sick of them and threatened them so hard that Cleopatra VII let a snake bite her tiddie until she died.

30 BC, that happened. The Macedonians were still using the traditional Egyptian style to portray themselves.

Below is the final example of Ancient Egyptian art, a graffito made by one of the last pagan Egyptian priests. In 394 AD:

This was like 60 years after Constantine mandated Christianity as the official Roman Imperial religion (and Egypt was still a part of that).

The only thing close to this now is that there are modern Chinese characters that were first carved into bone dice around 1250 BC. That means some of the Chinese script is 3200 years old.

...Of course there are also Hongshan Culture Pig Dragon amulets from after 4700 BC that kind of have contemporary Chinese iconographic elements. And those were carved by actual cavemen.

But it's not a 1 for 1 continuous line, so not entirely the same.

Ancient Egypt was nuts.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

OPS - Resort Villa in the Mountain: Interesting Soul Always Has a Place Read more: Link in bio! Photography: Ao Xiang OPS: Natural interest Beauty of tension is a kind of competitive power I prefer a state of conflict or tension. I don't like a state where only physical beauty works, because if it's just beauty, it is kind of boring. The project is located in Fengning Manchu Autonomous County in the middle zone between the farming culture of the Central Plains in the south and the animal husbandry culture in the north. The cultural features integrate the southern and northern cultures. It enjoys both Hongshan culture and Longshan type; it has delicate and deft style in Central Plain, with rugged and earthy characters from prairie… #china #chengde #fireplace #архитектура www.amazingarchitecture.com ✔ A collection of the best contemporary architecture to inspire you. #design #architecture #amazingarchitecture #architect #arquitectura #luxury #realestate #life #cute #architettura #interiordesign #photooftheday #love #travel #construction #furniture #instagood #fashion #beautiful #archilovers #home #house #amazing #picoftheday #architecturephotography #معماری (at Chengde) https://www.instagram.com/p/CiwLqJHMN9E/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#china#chengde#fireplace#архитектура#design#architecture#amazingarchitecture#architect#arquitectura#luxury#realestate#life#cute#architettura#interiordesign#photooftheday#love#travel#construction#furniture#instagood#fashion#beautiful#archilovers#home#house#amazing#picoftheday#architecturephotography#معماری

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jade de la Culture de Liangzhu

Les objets et les icônes en jade sont presque synonymes de la culture chinoise depuis des milliers d'années. Le jade (néphrite) fut travaillé pour la première fois en objets reconnaissables vers 6000 avant notre ère, pendant la période de la culture de Houli (c. 6500 - c. 5500 av. J.-C.). L'art du jade se développa à partir de cette époque pour atteindre son apogée à l'époque de la culture de Liangzhu (c. 3400-2250 av. J.-C.). Cette période vit également le développement de la stratification des classes établie au début de la culture de Yangshao (c. 5000-3000 av. J.-C.) et poursuivie par la culture de Hongshan (c. 4700-2900 av. J.-C.). Le jade, dont le travail prenait beaucoup de temps, était très prisé et seule la classe supérieure pouvait se l'offrir.

Lire la suite...

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A celadon jade toothed animal mask ornament, Hongshan Culture, circa 4000-3000 BC; 4 15/16 in. (12.6 cm.) wide.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Neolithic jade bird-head vorm finial, Hongshan culture, circa 3500-2500 B.C

Courtesy Alain Truong

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

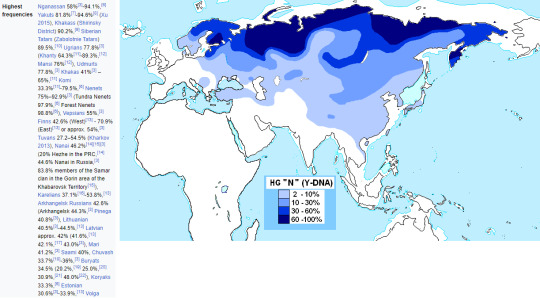

Dragon of the Hongshan Culture 4500-3000 BCE

I found this interesting. The Neolithic Hongshan Culture seems to host the oldest (to date) archaeological finds of clearly depicted dragon art in the world. The people that lived there had haplogroups that correspond very strongly with modern day Uralic, Baltic, and certain Turkic speaking populations. But those same haplogroups are found in very low frequencies in China today. Genetics is obviously more complicated than just haplogroups, and some of these populations are quite different from each other genetically, but it's an interesting piece of information nonetheless.

From WorldHistory:

"The earliest known depiction of a dragon is a stylised C-shaped representation carved in jade. Found in eastern Inner Mongolia, it belonged to the Hongshan culture, which thrived between 4500 and 3000 BCE."

From Wikipedia:

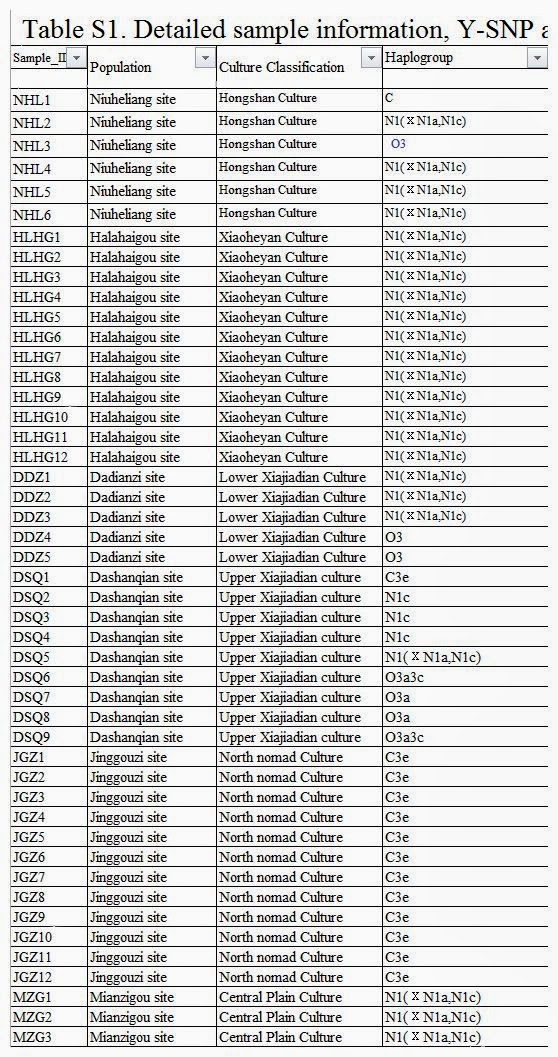

"A genetic study by Yinqiu Cui et al. from 2013 analyzed the Y-chromosome DNA haplogroup based N subclade; it found that DNA samples from 63% of the combined samples from various Hongshan archaeological sites belonged to the subclade N1 (xN1a, N1c) of the paternal haplogroup N-M231 and calculated N to have been the predominant haplogroup in the region in the Neolithic period at 89%, with its share gradually declining over time. Today, this haplogroup is found in northern Han, Mongols, Manchu, Oroqen, Xibe and Hezhe at low frequencies".

From NationalLibraryOfMedicine:

"The sequence of cultures include the Hongshan culture (6500–5000 BP), Xiaoheyan culture (5000–4200 BP), Lower Xiajiadian culture (4200–3600 BP), and Upper Xiajiadian culture (3000–2700 BP) (Figure 1). The Hongshan culture is one of the most advanced Neolithic cultures in East Asia, with social stratification, distinctive painted pottery and elaborate jade ornaments. Archaeological investigations suggest that hunting- gathering was the main mode of subsistence, but they also indicate early use of cultigens in the Hongshan Culture. The Xiaoheyan culture adopted the basic features of the Hongshan culture, but had a simpler social organization. It was followed by the Lower Xiajiadian culture, which was marked by a gradual shift to agriculture and the establishment of permanent settlements with relatively high population densities, while retaining some of the hallmarks of the Hongshan culture. It was replaced abruptly by a radically different culture, the Upper Xiajiadian, which was influenced by the Bronze Age cultures of the Northern China steppe.

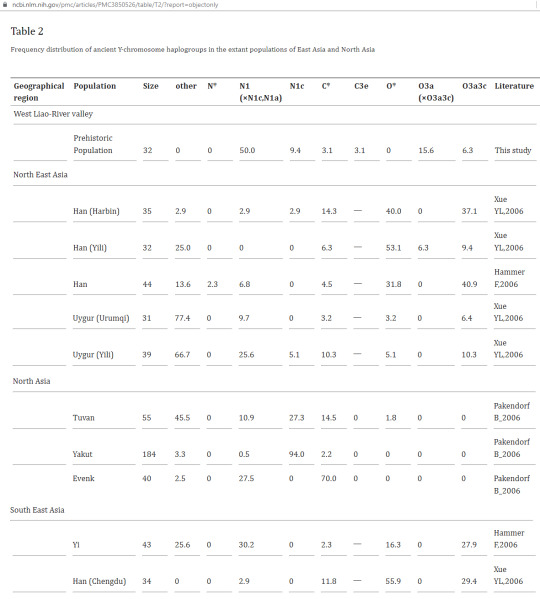

The most ancient populations of the West Liao River valley exhibited a high frequency (71%) of haplogroup N1-M231. Because of the short amplicons needed for the ancient samples, it was not possible to type the diagnostic site P43 of sub-haplogroup N1b, so samples that yielded negative M128 and TAT mutations were defined as N1 (xN1A, N1c). Besides being the only haplogroup in the Halahaigou site, N1 (x N1a, N1c) was also predominant in the Niuheliang and Dadianzi sites. In the Dashanqian site, there were two subtypes of N1-M231: N1 (xN1a, N1c) and N1c-TAT. One of the nine Dashaqian samples was N1 (xN1a, N1c), and three were N1c (Table 1). N1 is particularly widespread in northern Eurasia, from the Far East to Eastern Europe. Its subtype, N1c, is found at low frequency but has high STR variability in northern China, suggesting that this region was N1c’s centre of expansion.

A single instance of O3a (xO3a3) was observed in the Neolithic Hongshan and Xiaoheyan sites, although this haplogroup was observed in just under half of the Bronze Age individuals. The Upper Xiajiadian individuals of the late Bronze Age had different subtypes of O3a-M324, O3a3c-M117. O3a-M324 is found today in most East Asian populations, and its subtype O3a3c-M117 occurs at the highest frequency in modern Sino-Tibetan populations.

The West Liao River valley was a cradle of Chinese civilization, together with the valleys of the Yellow River and Yangtze River, and there is considerable interest among scholars in the origin and expansions of the ancestors of the present-day inhabitants. Extensive analyses of extant populations have revealed that the most common Y chromosome haplogroup today is O-M175 (58.8%, n=176), followed by C3-M217(23.8%), N-M231(8.5%), and several relatively rare haplogroups, namely D-M174, Q1a1-M120, and R-M207. Our data reveal that the main paternal lineage in the prehistoric populations was N1 (xN1a, N1c), present in about 63% of our combined sample of all cultural complexes. It was the predominant haplogroup in the Neolithic period (89%), and declined gradually over time (Table 1). Today it is only found at low frequency in northeast Asia (Table 2). There appears to be significant genetic differences between ancient and extant populations of the West Liao River valley (P<0.001)."

#anthropology#genetics#archaeology#history#chinese history#dragons#art#ancient art#finland#turkic#museums#ancient history#neolithic

14 notes

·

View notes