#I can say 'Oscar Wilde was a good playwright' and 'Oscar Wilde was not a good person' in the same breath that's not a contradiction

Text

LONG POST - Cancel Shakespeare? No way!

(NYTimes) Make Shakespeare Dirty Again

Aug. 13, 2023, By Drew Lichtenberg

It seemed, for a moment, that Shakespeare was being canceled. Last week, school district officials in Hillsborough County, Fla., said that they were preparing high school lessons for the new academic year with some of William Shakespeare’s works taught only with excerpts, partly in keeping with Gov. Ron DeSantis’s legislation about what students can or can’t be exposed to.

I’m here to say: Good. Cancel Shakespeare. It’s about time.

Anyone who spends a lot of time reading Shakespeare (or working on his plays, as I have for most of my professional career) understands that he couldn’t have been less interested in puritanical notions of respectability. Given how he’s become an exalted landmark on the high road of culture, it’s easy to forget that there’s always been a secret smugglers’ path to a more salacious and subversive Shakespeare, one well known and beloved by artists and theater people. The Bard has long been a patron saint to rebel poets and social outcasts, queer nonconformists and punk provocateurs.

Yes, Shakespeare is ribald, salacious, even shocking. But to understand his genius — and his indelible legacy on literature — students need to be exposed to the whole of his work, even, perhaps especially, the naughty bits.

The closing lines of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 20, addressed to the poem’s male subject, are among the dirtiest — and hottest — of the 16th century. “But since she pricked thee out for women’s pleasure, / Mine be thy love and thy love’s use their treasure.” A favorite trick of Shakespeare’s was to play with word order, especially when he wanted to disclose something too daring to be said in a more straightforward way, such as the love that dared not speak its name. The untangled meaning here: Your love ultimately belongs to me, sir, even if women (sometimes) enjoy your prick. Or, from the neck up you are as beautiful as a woman, and from the waist down you are all man.

Sex is one thing. The plays are also astoundingly gory. The bloody climax of “King Lear” so horrified the playwright Nahum Tate that he felt compelled to rewrite its ending. Tate’s sanitized version of “King Lear,” premiering in 1681, held the stage until 1838. In the 18th century, Voltaire called “Hamlet” the apparent product of a “drunken savage” who wrote without “the slightest spark of good taste”— which didn’t stop Voltaire, who also recognized Shakespeare’s “genius,” from openly borrowing from the Bard for one of his own plays.

In 1872 in “The Birth of Tragedy,” Friedrich Nietzsche praised this savagery. To him, Shakespeare contained the ne plus ultra of grisly truths. Hamlet, he wrote, “sees everywhere only the horror or absurdity of existence.” Nietzsche being Nietzsche, he considered this a good thing. Art, wrote Nietzsche, transforms “these nauseous thoughts about the horror or absurdity of existence into notions with which one can live.”

In light of Nietzsche’s counterintuitive epiphany, the notion of Shakespeare-the-hipster caught fire. Hamlet, uniquely among male roles in the classical canon, became an aspirational part for female theatrical stars looking to prove their bona fides and upend gender preconceptions: Sarah Bernhardt most famously, but also the great Danish actor Asta Nielsen. Shakespeare’s sonnets were a source of succor to decadent aesthetes such as Oscar Wilde, just as they had been to Charles Baudelaire. The writings and teachings of queer poets such as W.H. Auden and Allen Ginsberg suggests they saw themselves in Shakespeare’s works, as did anti-racist writers from James Baldwin to Lorraine Hansberry and Ann Petry.

Where the avant-garde led, pop culture followed. Shakespeare’s plays have always lent themselves to all manner of interpretations and they found new life in the postwar era, with landmark works like Basil Dearden’s “All Night Long,” a neo-noir film from 1962, which set “Othello” in a British jazz soiree. Franco Zeffirelli’s “Romeo and Juliet” in 1968 plugged into a different cultural zeitgeist, capturing onscreen the summer of love, while Roman Polanski’s film version of “Macbeth” in 1971 feels like an encomium for the dying utopian dreams of the ’60s.

In the transgressive ’90s, Shakespeare was everywhere: taboo, art house, alternative and cool. Gus Van Sant’s “My Own Private Idaho” reimagined Prince Hal and Hotspur as gay grunge gods and Baz Luhrmann’s “Romeo + Juliet” featured Leonardo DiCaprio at the peak of his androgyne allure. Even “Shakespeare in Love,” a relatively middlebrow Oscar winner, presented a vision of the brooding, bearded, sexy Shakespeare, as embodied by Joseph Fiennes.

In many other cultures, the bawdy lowbrow and the poetic highbrow are often personified by separate champions: In France, it’s Rabelais and Racine; in Spain, Cervantes and Calderón. In English literature Shakespeare has always combined both brows into something rich, special and strange. In “A Midsummer Night’s Dream,” one of Shakespeare’s most magical and sensual plays, Bottom — a man with the head of a donkey — spends the night in bed next to the fairy queen. He wakes up having had something close to a religious experience. Every play in the canon features something similarly subversive and transcendent — and all of them are essential.

One can no more take out the dirty parts of Shakespeare than one can take out the poetry. It’s all intertwined, so that Shakespeare seems almost purposefully designed to confound those who want to segregate the smutty from the sublime. His work is proof that profundity can live next to, and even be found in, the pornographic, the viscerally violent and the existentially horrifying. So if you’re looking for sex, gore and the unspeakable absurdity of existence in Shakespeare, you will definitely find it. That’s the genius of Shakespeare. And it’s precisely what makes his work worth studying.

Drew Lichtenberg is a lecturer at Yale University and the resident dramaturg at the Shakespeare Theater Company in Washington, D.C.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bro dark academia is literally not that deep a bunch of people were like "old books and soft lighting and Oscar Wilde quotes are pretty let's look at those things to make us happy" and now a bunch of people are like that's classism? My man poor people can like argyle and brick buildings we all know that actual academia has major issues it's literally just an aesthetic relax

#Source im fucking poor dude I just like old books#Edit I think people also point out racism and sexism in classic lit as reasons why da is bad and if they don't they should#But like here's the thing#We aren't stupid. We know that writers from a hundred years ago were racist and sexist#Writers now are racist and sexist#We read it critically to learn if we're doing it correctly#Like if you're in to Da enough to be reading the books and shit you should also be reading critically#My favorite playwright is Oscar Wilde#I think the way he uses timing and dialog is excellent I think his humor is hilarious and I think I can try my best to use him to make#Myself a better writer#Was he antisemitic? Yes. He wasn't a nazi or anything but most people then were and he's no exception#NOT AN EXCUSE IT'S STILL BAD#I can say 'Oscar Wilde was a good playwright' and 'Oscar Wilde was not a good person' in the same breath that's not a contradiction#I'm reading critically. I'm understanding the things that were bad. I'm using his work to learn about his time#If we never look at works that aren't perfect art won't exist anymore#And if we don't understand that otherwise good seeming people can be hateful#That people can be complicated#That being gay or an artist or working on women's magazines doesn't stop someone from being antisemitic#Then we develop a black and white view of the world that let's evil take over because it's hiding itself#I got way off topic#Most folks with da blogs don't care this much they just like the brick buildings with gray filters and good for them they're fucking pretty

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

My List of Evidence that proves The Curator from The Dark Pictures Anthology is Death.

ALRIGHTY!! It’s time for all the evidence I found in Little Hope that supports the “Curator is Death” theory. And actually, these hints are even less subtle than they were in Man of Medan.

Shoutout to @cynical-sprite and @scandinavian-in-disguise, because you guys are the only ones I’ve seen post about this, and I love talking about this topic!

I’m on mobile, and I’m not sure how to add a “read more” thing. (I’ll figure it out and edit once I do)

SPOILER ALERT FOR LITTLE HOPE

You’ve been warned, Because seriously, if you use any information regarding this theory, you can figure out the ending before it’s revealed.

Ok! Here we go!

1) All of the following quotes.

The quote is in bold, my thoughts are italicized.

“I’m not supposed to interfere, you see. Not...my...place...apparently.” As we’ve seen in Man of Medan, whenever there’s a possibility of a character dying, you can see the Curator in the background. It makes sense. He’s just observing. And just because he can’t interfere, doesn’t mean we can’t.

“The fire? No, there was nothing you could’ve done about that. What’s happened has happened. Or has It?” This line was delivered as if it was an event he remembered witnessing. This was one piece of evidence used in predicting the ending.

“You have a funeral to attend, off you go. Have fun!” “I do enjoy a good funeral” I mean, of course it would make sense for Death to enjoy funerals. 🤷

“Not that there’s anything particularly wrong with death.” *smirks* In my opinion, this just seemed like he was talking about himself. I don’t think it’s solid enough to count as evidence, though.

“Another instrument of death added to the groups collection. Good work!” The wording of this seemed very strange to me. But it was the knife used with one of the witch trial deaths, so that might be why he worded it this way.

“I met him once you know. I meet everybody ‘once’.” You only die once. That’s all I have to say.

“I’ll leave you now with some wise words from a great Irish playwright I once met...in Paris, I believe.” I looked it up. The playwright is Oscar Wilde. He passed away on November 30th, 1900 in Paris France.

“But we will meet again. At least one more time.” This was during his closing monologue. I took it as, no matter if you play the next game or not, you will be meeting him again. Because everyone dies.

2) His reactions to the number of survivors in each cutscene.

If you remember in Man of Medan, the more characters that were still alive, meant the curator has a certain...how should I word it...sassy attitude about it. Like he didn’t want that to happen.

In Little Hope, there was no sassiness in regards to the survivors. He was just nonchalant about them. It felt wrong. (This was another clue to me that the main events of the game were a hallucination or something.)

The only time he gives you attitude is with the best ending: Andrew lives, forgives Megan, everyone else “survives” their doubles, and Vance forgives Andrew. (I’m only 95% sure that these are the correct outcomes to get this ending, I will be double checking this).

Only then do you get the sass and slow sarcastic applause.

3) His response to taking or leaving the gun

There are 2 times you’re given the option to pick up a weapon. But we’re only going to focus on the gun.

While he does react to the knife, his reactions to the gun are MUCH more...dramatic.

If you leave the gun, you get the same sass that you received when the characters were alive in Man of Medan. It then turns to disappointment. Like he was hoping you’d pick it up.

But then you get this quote, if you take the gun:

“That gun might prove to be a lifesaver...don’t you think? Or the exact opposite.”

It’s the last part that worried me. Because not only was he glad you have the gun, he’s smiling at you while he says it. Because he knows it’s going to be the opposite. Or rather, it’s possible it could.

This leads me to my final point

4) The Curators secret appearance in Little Hope.

As stated above, in Man of Medan, he shows up in the background when there’s the possibility a character could die. This fact should also be true in Little Hope, because obviously, this game is filled with so much more death, he should be everywhere, right? No. He wouldn’t. But that doesn’t mean he never showed up.

In all my searching, I’ve come to find that he appears ONLY ONCE.

And that’s here:

(Screenshot taken from YouTube, arrow added by me)

Which ending is this?

The bad one. The one that ends with Andrew committing suicide, by blowing his brains out.

This is the reason why the Curator reacted the way he did about if you took the gun or not.

Andrew’s death is the ONLY death that actually happens in Little Hope.

(No, the fire incident does not count.)

One additional note, I’d like to add. Both Dark Picture games so far have had the supernatural buildup and the “it’s all in their head” ending. I’ve seen people say things about being disappointed that there isn’t a supernatural element, like Until Dawn.

What I don’t think people realize, is the fact that there is a supernatural element in the Dark Picture Anthology, and it’s The Curator.

Anyways, that’s all the evidence I have on the curator being death. What do you think? I love to hear feedback and/or talk about the game!

#i totally think the curator is death#the dark pictures little hope#the dark pictures anthology#curator#little hope#man of medan#death#the curator#supermassive games#video games

187 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you think blogs with cool library photos and Oscar Wilde quotes are just intrinsically better than all the others without these two seemingly unrelated elements? I do but trying to find some connection from one thing to the other is quite maddening. Wilde probably never took a photograph because, well, 19th century cameras were the size of most furniture and they sucked. Originally, they were proof of sorcery but that wore off and they were pretty unremarkable by his time. Okay, that quickly became a rather dull bewilderment. First case of someone ever being flummoxed to sleep. I really would like to read your answer to my question please. Thank you very much.

Holy moly Dreamy… this was a lot to unpack…. I wouldn’t say they are necessarily better… but for me, I love library/books photos and I love quotes so it’s an all around win-win when both are together in a post. And Oscar Wilde is just a fascinating person on his own… and he was a poet/playwright whose works can be found in a library…. so perhaps that’s why those kind of posts hit you just right?

Now go turn your brain off and get a good night’s sleep. I’m sure this puzzle will sort itself out for you by morning… btw thanks for the interesting tidbit on 19th century cameras being seen as some mystical contraption when they were first invented & used 😊

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shadowhunters Short Story #64 part 2.

Anna grins at her brother and cousins while adjusting Benji in her arms. Their excitement is certainly infectious.

“Yes you can come in and meet Benji if you be quiet and calm, Ariadne is asleep, she is very tired and finding it very difficult to adjust to being up all hours with Benji.” Anna firmly says, looking directly at Matthew, who is definitely the one who makes the most noise.

“I will be good Anna, I promise!” Matthew exclaims, still bouncing on the balls of his feet with excitement.

“Alright, come in then.” Anna says, holding the door open and letting her brother and cousins in past her.

“I get to hold him first!” Matthew exclaims, as he and the others settle onto the couch while Anna closes and locks the door.

“No, I get to hold him first, then Daisy, then you, Kit and Tom and Alastair can decide amongst yourselves who gets to hold Benji next!” James says in an informative tone, as though this is a fact, pointing between himself, Cordelia, and the other Merry Thieves.

“But I am Anna’s favorite cousin, so I should hold him first, besides Kit already held him when he was here earlier with his parents, so he definitely should not get to hold him first.” Thomas calmly says.

“Ha! You wish Tommy, I am Anna’s favorite cousin, right Anna?” Matthew asks in a sure tone, turning his gaze on her, his green eyes glinting with delight.

“Lucie is my favorite cousin, where is our darling Lu anyway?” Anna asks, surprised that Lucie has not turned up with The Merry Thieves to meet Benji, she loves babies and is always pestering James and Cordelia to give her a niece or nephew, similarly to how she would pester Tessa and Will for a sibling.

“Anna how very dare you! My beloved Lucie will not be joining us today I am afraid, she is not feeling well.” Matthew explains, going from heart-broken and mortally offended, to completely calm in just minutes.

“Under the whether or pregnant?” Thomas teases. James’ eyes widen and Matthew quickly holds his hands up, as though surrendering to something.

“No! Please do not attack me Jamie, I promise Lucie is not pregnant, she really is just sick, with a cold!” Matthew exclaims, remembering the time just a few months ago when Lucie had really thought she was pregnant and James had flown at Matthew in a rage when he found out. No one had ever seen Jamie so angry, especially not with his parabatia.

“Good Lord boys are dramatic.” Anna says in an amused tone. “Here Cordelia, you may hold Benji first, and I will go put the kettle on. If these hooligans wake my wife, Daisy, you have my full permission to kill them if it will shut them up.” Anna says in a playful tone, lowering the baby into Cordelia’s arms, where he quickly settles. Cordelia grins up at Anna.

“Yes m’am!” She laughs. She then turns her attention to Benji and strokes his little cheek, bringing her back to when her baby sister Evangeline had been born 5 years ago. “Hello little Benji, you are so adorable!” Benji wraps his hand around Cordelia’s finger and snuggles closely into her.

“He could so easily pass for Ariadne’s biological child, its’ not just his dark hair and skin color that are the same, he has the same nose and mouth shape as her too, how odd!” Matthew notices, leaning against Cordelia and stroking Benji’s tufts of hair.

“You are seeing things Matthew, he looks nothing like Ari.” Thomas says, straining to get a proper glimpse of the baby.

“Ari must be so happy to finally be a mother, when she was engaged to Charles I heard her telling mama that she wanted a quick wedding because she wanted to start trying for a baby as soon as they could, of course Charles Buford would have been so lucky as to have someone as lovely as Ariadne have his children, my brother is such a slime-ball, I am glad Ariadne is with Anna now, and not my know-it-all older brother.” Matthew says in an exasperated tone, rolling his eyes at the thought of his smug brother.

“I really do not understand how Charles is your parents’ child, Henry and Charlotte are so very kind and lovely, as are you Matthew, but Charles is the complete opposite.” Cordelia says in a confused tone.

“Math has a conspiracy theory that Charles was swapped at birth with some other baby, and that his true brother is out there somewhere with some dreadfully stuck up, boring and cowardly family. He has gone so far as to ask Uncle Jem to help him prove that theory and check all the records of baby boys born in The Basilas the same day as Charles.” James says in an amused tone.

“You will not be laughing when Uncle Jem and I prove my theory right and find my real brother, who also likes Oscar Wilde- my dog and the playwright- and has an amazing sense of fashion like me, James Herondale.” Matthew says in a sure tone, just as Anna comes back in, carrying a tray with a teapot and several cups.

“Aunt Sophie is right Matthew, you do have your mama’s over-active sense of imagination.” Anna says in a light tone, setting the tray down on the coffee table.

“Thank you! I think.” Matthew says, furrowing his brow in confusion. “Anna, I am going to be Benji’s Godfather, aren’t I?” He adds, as Cordelia passes Benji back to Anna.

“No, but Cordelia we most certainly want you to be his Godmother.” Anna softly says.

“M-me? A-are you sure?” Cordelia stammers, looking at Anna with wide eyes full of shock but also delight. She had never expected this, and is honored to even be considered as little Benjamin’s Godmother.

“Absolutely, you are the most sensible one among The Merry Thieves, you and Thomas. We trust you to be a wonderful guide and influence for Benji.” Anna says, reaching over to squeeze her friend’s hand.

“Excuse you! I am sensible!” Matthew exclaims in an offended tone.

“As am I!” James chimes in.

“Matthew, dear Matthew, I do love you so but you are the furthest from sensible a person could be, and I love you for it. And Jamie, my lovely baby cousin, you are quiet sensible, but not as much as Cordelia or Thomas I’m afraid, but don’t take offense boys, it simply means you will be Benji’s fun uncles that get to take him on adventures and teach him things you probably should not, while Cordelia and his Godfather are going to have to do the boring work, like teaching him about religion and helping us make sure he grows up sensible.” Anna explains gently, knowing that both Matthew and James will adore the idea of being the fun uncle, to Benji.

“Fine, but only if I get to hold him now!” Matthew bargains.

“Deal, come get him and watch him for me for a few minutes while I check on Ariadne.” Anna says, beckoning her cousin over.

A few minutes later Matthew is happily seated between James and Thomas, cradling little Benji and smiling like he just won all the riches in the world.

“We are going to have so much fun together Benji! I will buy you the most fashionable clothes on the market and all the books your heart could desire, especially poetry and especially Oscar Wilde, and you will love my dog who is also named Oscar Wilde. Oh, now that I come to think of it Benjamin, I wish I had of named Oscar something else, perhaps Dorian, so I could name my first son Oscar.” Matthew says, his tone turning downtrodden when he realizes what a mistake he has made.

“Lucie would never let you name her son Oscar, she has her children’s names chosen.” James informs Matthew, which surprises him. Lucie has a running list of names on the go at all times, but Matthew thought they were simply for her characters in her stories, or maybe to have in case her parents finally gave into her pleas and had another baby.

“She does?” Matthew asks. James nods.

“Abigail Teresa for a girl and Sebastian William for a boy.”

“But I want my children to have my parents names as middle names! Oh and Lucie is so stubborn she will never change her mind, I may have to brake up with her.” Matthew jokes with a solemn shake of his head.

“Let me hold him now, Fairchild, you have had him long enough.” Alastair declares, holding his arms out for little Benjamin.

“Fine but only for a few minutes, he was having fun with me!” Matthew says, gently placing the baby in Alastair’s arms.

“He’s asleep.” Alastair observes, adjusting Benjamin’s blankets around him.

“Yes well he heard your boring voice and conked right out, you cannot blame the little fellow, I often think of conversations we have had when I have trouble sleeping, and it helps me drift off right away!” Matthew teases, grinning playfully at Alastair, who he is now good friends with. Alastair makes Thomas happy, and what makes Thomas happy, makes the rest of The Merry Thieves happy.

“This little one makes me want a baby.” Thomas quietly says, one arm around Alastair's waist, his chin resting on his boyfriend’s shoulder, the other reaching out to stroke Benji’s cheek. Alastair's eyes widen in shock. He and Thomas had briefly discussed having children, but agreed to wait a few more years at least, until they are older.

“I-I thought we had agreed to wait!” Alastair stammers. Thomas chuckles and kisses his cheek.

“We did and we will, but this little one just makes me impatient. However I am sure we will be first on call as babysitters, especially seeing as you and Ariadne are such close friends.” Thomas gently says. A few years ago when Charles broke off his engagement to Ariadne, and Alastair broke off his relationship with Charles when he realized Charles would never admit to loving him or commit to him, Ariadne and Alastair found solace and comfort in another, they both knew what is was like to be attracted to the same sex in an un-accepting time, and they both knew how awful Charles could be. They took to meeting up at least once a week and have done so ever since, and now they are the very best of friends.

The Merry Thieves spend the next few hours fussing over their new nephew and bonding with him, while occasionally being scolded by Anna for being too loud and chancing waking Ariadne.

It is just past 4 in the evening, when Ariadne pads into Benjamin’s nursery, rubbing sleep from her eyes, while Anna sits in the rocking chair, reading to her son.

“Anna, have I been asleep all day?” Ariadne asks in a tired, breathy tone, rubbing at her eyes.

“Yes love, you clearly needed it. Did you sleep well?” Anna asks, taking her hand and drawing her down onto the ottoman beside the rocking chair.

“Yes, wonderfully, thank you. How has our boy been?” Ariadne asks, reaching out to stroke Benji’s cheek.

“Good as gold as usual, he has been fussed over all day. First by my parents and brothers and then The Merry Thieves came around, all apart from Lucie. Matthew adores his role as Benji’s fun uncle, and I asked Cordelia to be Benji’s Godmother.” Anna tells Ariadne, one hand laced through with hers and the other holding Benji.

“Sounds like you had a very busy day, are you not tired?” Ariadne asks in a concerned tone. Anna has not struggled to adjust to their new sleep schedule with Benjamin the way Ariadne has, but she still needs her rest and sleep, no one is invincible.

“A bit, but as I said before Benjamin is more than worth it.” Anna says in a loving tone, her gaze returning to her son.

“You should go rest for an hour now, let me take Benji. You rest and Benji and I will make dinner and then wake you when it is ready, we have not had a proper meal since we adopted him, now is as good a time as any to start eating meals again, and it will help us both with our energy.” Ariadne says.

“Are you sure?” Anna asks, both wanting to lie down and rest for a while, and also wanting to let Ariadne rest as much as possible. Ariadne smiles softly and kisses Anna’s cheek.

“I am sure love, you need your rest and I want some quality time with my boy.”

When Anna goes into the bedroom, Ariadne pulls out one of her heavy winter shawls, and fastens it into a sling across her chest, where she can lay Benji so that he can be close to her but she can also have both her hands free.

As Ariadne moves around the kitchen, preparing dinner for her family, she quietly hums an old Indian lullaby she seems to remember someone (Likely her birth mother) singing to her when she was very small, before she was adopted. At this moment, her heart could not possibly be more full, she gets to wake up next to and live a wonderful life with the love of her life, her amazing Anna, she does not have to hide who she is anymore or bare a man’s touch, her parents are extremely loving, caring and supportive, she has more friends than she ever thought she would, and she has a beautiful and wonderful baby boy, who makes her heart soar with happiness every time she looks at his gorgeous little face.

At one stage, all 3 people in this little family were lost in someway. Anna had been lost in her grapple with her sexuality and gender for years, then she had been lost in her grapple with love and trusting someone with her heart, Ariadne had been lost from a family at a very young age, before she was taken in by The Bridgestocks, and she too was lost in the struggle of being a woman exclusively attracted to women, and little Benji had been lost from his birth family too.

Now, together, the 3 of them are found and a family, the most perfect family one could ask for.

#anna lightwood#Ariadne Bridgestock#thomas lightwood#alastair carstairs#christopher lightwood#james herondale#Matthew Fairchild#charles fairchild#henry branwell#charlotte fairchild#Cordelia Carstairs#tessa gray#tessa herondale#jem carstairs#james carstairs#will herondale#william herondale#Brother Zachariah#Cecily Herondale#Cecily Lightwood#gabriel lightwood#lucie herondale#sona carstairs#elias carstairs#grace blackthorn#grace cartwright#oscar wilde#dorian gray#the shadowhunter chronicles#the last hours

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Songs that are about Johnny Marr (probably)

THE SMITHS

The Smiths

Hand In Glove → the lyrics are about a deep friendship and Johnny himself said he thinks it’s about his relationship with Morrissey because they were “only hanging out with each other at the time”.

Meat Is Murder

I Want The One I Can’t Have → all about unrequited love.

A possible reference in the title to Elizabeth Smart’s novella By Grand Central Station I Sat Down And Wept – “I want the one I want.”

Also: “Meet me in the Alley” is a 1972 song by John Mars.

Well I Wonder → a desperate plea by Morrissey for someone to keep him in mind.

There are several loans from By Grand Central Station... (which by the way is about a deeply emotional, doomed and unrequited love), namely:

“Well I wonder, do you hear me when you sleep?” / “Is it possible he can not hear me when he lies so close, so lightly asleep?” , “My dear, my darling, do you hear me when you sleep?”

“This is the fierce last stand of what I am.”

This song was never performed live and Johnny said it was because they were afraid they wouldn’t be able to capture its full magic, which makes sense, but I also get the feeling that this song was particularly special to both Morrissey and Johnny, for reasons which went beyond its lyricism and music.

The Queen Is Dead

I Know It’s Over → conceived just a few months after Johnny married his girlfriend Angie while The Smiths were on tour in the US. Morrissey was Johnny’s witness. The lyrics mention a wedding and a failed relationship that “never really began” because “love is natural and real, but not for such as you and I, my love” (where “natural and real” could easily be interpreted as “straight”.)

The Boy With The Thorn In His Side → even though Morrissey said that this was a song about his tormented relationship with the music industry (that being the “thorn” in his side), in my opinion there’s also another interpretation. Just as in Well I Wonder, there are a few loans from By Grand Central Station… namely: “How can they see the love in our eyes and still they don’t believe us?” / “They intercepted our glances because of what was in our eyes.” “And if they don’t believe us now, will they ever believe us?” / “Did they see such flagrant proof and still not believe?”. These are especially relevant because they come from a point in the book in which the author is specifically talking about her love for a married man (poet George Barker) and about how they were attempting to see each other in spite of that, which caused them to get arrested while together in Arizona for “moral turpitude”.

There Is A Light That Never Goes Out → references being driven around in someone’s car. Morrissey and Johnny apparently used to go on long car rides together, Morrissey talked about how he found cars to be “erotic” and there are multiple examples of that in his lyrics (see This Charming Man, That Joke Isn’t Funny Anymore etc.). Also, the lyrics are, once again, about unrequited love.

Strangeways Here We Come (the pining here was at its finest imo)

A Rush And A Push And The Land Is Ours → the title is a reference to a traditional Irish rallying call which Oscar Wilde’s mother, who wrote Irish nationalist prose and poetry, used to urge the Irish to rise up against the British army.

“Some eighteen months ago” could be a reference to Oscar Wilde being sentenced to hard labor for soliciting male prostitutes.

The lyrics are about the “pain and strain” of being in love despite not wanting to. Also, the way he sings “so phone me, phone me” sounds like he’s saying “f*ck me”. (I thought I was the only one who thought that, but apparently not.)

I Started Something I Couldn’t Finish → the lyrics are about going too far with someone who can’t/doesn’t want to be pushed.

Another reference to “eighteen months’ hard labor”.

The “Okay Stephen, do that again” at the end is aimed at producer Stephen Street, but Morrissey is also called Steven. Why was that left in the recording? Was it fully intentional? Who wants Stephen to do what again? Maybe the other person mentioned in the song doesn’t actually mind being pushed out of their comfort zone by Morrissey, they just lack the courage to seal the whole deal for whatever reason.

Girlfriend In A Coma → according to the lyrics, Morrissey doesn’t seem to like this woman, yet he feels guilty about it and doesn’t wish her ill. Could this be a reference to Angie Marr, who he sees as an obstacle between him and Johnny, despite having a good opinion of her as a person?

Stop Me If You Think You’ve Heard This One Before → by now, Morrissey may have realized that he has written an awful lot about being in love with someone who doesn’t reciprocate. Also, his love for this other person must be so obvious by now, he’s said almost everything on the subject and yet he still wants to make clear that: “Nothing’s changed, I still love you, only slightly less than I used to, my love.” By now, his working relationship with Johnny was starting to deteriorate. Another interesting note is: “Oh, who said I’d lied to her because I never? I never!”. While this is grammatically incorrect, it’s also a common way of speaking in most Northern cities, so this reads like a quote that someone may have uttered at some point and this may be why, when called out on it, Morrissey said it was meant to be written that way. It’s worth pointing out how Morrissey liked to correct Johnny’s grammar in interviews and he even mentioned in his Autobiography how Johnny’s way of speaking was “shockingly bad”.

Death At One’s Elbow → the song’s title was taken from the diaries of 60s playwright Joe Orton, beaten to death with a hammer by his lover Kenneth Halliwell.

Johnny’s opinion on the song was ambivalent. He stated that: “It was good sometimes to have a track that wasn’t trying to win the war like There Is A Light That Never Goes Out,” he said. "It was almost like, ‘We have the right to be slightly less intense.’ I liked Morrissey’s singing and I liked my own backing vocals” and yet, when asked by Johnny Rogan about it for his book Morrissey & Marr: The Severed Alliance, he sounded much less pleased with it, saying: “Oh God, did we really write that?”.

I Won’t Share You → widely believed by everyone to be about Morrissey’s possessive feelings towards Johnny (who not only didn’t mind, but seemed actually quite pleased about it).

Others

Wonderful Woman → It was originally titled “What Do You See In Him?” and included lyrics such as:

“Cheat the Life out of me as you walk hand in hand / And I try, and I try, but I will never understand / What do you see in her?”

“That she will plague you / And I will be glad / Yes, she will leave you / And I will be glad.”

The final version, albeit quite different, is still about a woman who seems quite unpleasant but to whom the protagonist feels irresistibly drawn to.

With the final: “When she calls me I do not walk, I run” there’s an acknowledgment of co-dependence in the relationship but, even though the first person is used, this could have been a way to write from someone else’s point of view. Specifically, the boyfriend of someone with a very domineering personality. (Basically, he’s writing from Johnny’s perspective).

Ask → the lyrics are about being too shy to make a move on someone, yet Morrissey seems to be eager to take on board whatever the other person has in mind. There’s pining and there’s the possibility of a relationship which looks promising but never amounts to anything substantial because the people involved don’t have the courage to take it any further, despite wanting to.

These Things Take Time → mentions of a relationship which is impeded by the fact that the other person is engaged to someone else (“I’m spellbound, but a woman divides”). Johnny was already with Angie at the time.

“And the hills are alive with celibate cries”. Morrissey had been talking to the press about being celibate and not really interested in romantic/sexual relationships, but the fact that the object of his desire was someone he knew he couldn’t have could have been part of the reason why he felt he had to take that stance.

Also, it seems like he already felt like this relationship wouldn’t last, with the other person “leaving him behind” in the end.

Is It Really So Strange? → I’m not so sure about this one, but I’m including it because the lyrics are about traveling from North to South and about loving someone in spite of unfavorable circumstances. Also, according to Johnny (from Mozipedia): “Road trips were a big part of the group. We opted to live in Manchester most of the time but were always traveling back and forth to London. It was in cars on the motorway where myself and Morrissey did a lot of our profound talking and thinking and listening. We loved it, because we’d take off at half three in the morning back to Manchester or down to London, just razzing about. That came out in ‘Is It Really So Strange?’”.

As a matter of fact, Morrissey included the track on Rank, which he compiled alone a year after the band’s demise, and I feel like every song on that record was put in that particular order for a particular reason (if you look at the tracklist it basically tells the whole story of The Smiths, from start to finish… he even included The Draize Train which he claimed he didn’t like, which is why he refused to put lyrics on it, so I can only assume he did that as a conciliatory gesture towards Johnny).

I Keep Mine Hidden → the last song The Smiths ever recorded, it is, like “I Won’t Share You”, widely believed to be a direct message from Morrissey to Johnny, who was about to leave the band. A plea for understanding, he seems to imply that for Johnny is much easier to lie (about what?) while hiding in plain sight (“But it’s so easy for you, because you let yours flail into public view”), while Morrissey is forced to keep HIS hidden. IT could be his emotions and the fact that he feels the need to repress them because of some trauma in his past (“I’m a twenty-eight digit combination to unlock, with a past where to be touched meant to be mental.”), but IT could also be a relationship. Johnny was married, while at the time Morrissey showed no public signs of being involved with anyone and had yet to relinquish his celibate image, which may have been frustrating if he was actually interested in someone but couldn’t voice it.

MORRISSEY

Viva Hate

Alsatian Cousin → literally the first sentence on the first record Morrissey released post-Smiths is: “Were you and he lovers? And would you say so if you were?”.

While the rest of the song is pretty ambiguous is interesting to note that, according to Mozipedia, Johnny was, at the time, the proud owner of two Alsatian dogs.

Angel Angel Down We Go Together → Morrissey himself admitted that this song was about Johnny. He also said it’s the only song he’d written with him in mind, post-Smiths, and that it was about how sorry he felt to see him being taken advantage of by the music industry. While the full truth of this statement may be debatable, it’s still worth noting how the lyrics end with the repeated: “I love you more than life”.

Late Night, Maudlin Street → While Morrissey said that this song was about his isolating childhood during the 70s, I think the lyrics go much deeper than that.

Apparently, when Johnny wanted to leave the band, Morrissey took it badly enough for people to start worrying about the fact that he might take his own life. Both Stephen Street and Grant Showbiz admitted to this, with Showbiz even spending the night at Morrissey’s house to keep an eye on him.

There’s also a rumor about the fact that Morrissey actually did attempt to kill himself by baking a cake with loads of sleeping pills in it, eating it and then phoning Johnny, admitting that he loved him and asking him to come seeing him before he died, with Johnny calling an ambulance instead.

(“I came home late one night, everyone had gone to bed, nobody stays up for you, I had sixteen stitches all around my head / The last bus I missed to Maudlin Street so, he drove me home in the van...”)

This would also explain the lyrics: “And I know I took strange pills, but I never meant to hurt you”.

If this story was true, then I feel like moving away from Maudlin Street could actually be a metaphor for committing suicide.

(“Good-bye house, forever! I never stole a happy hour around here”,

“I am moving house, a half-life disappears today / Every hag waves me on, secretly wishing me gone / Well, I will be soon / Oh, I will be soon.”)

There are also more loans from Elizabeth Smart’s By Grand Central Station… namely:

“They took you away in a police car / Dear Inspector, don’t you know? Don’t you care? Don’t you know about love?”.

This part comes from the same chapter which probably inspired part of the lyrics for The Boy With The Thorn In His Side and which is about people putting themselves between a loving couple.

Also, according to Mozipedia, during the making of Viva Hate, Morrissey prepared the artwork for the final Smiths single, Last Night I Dreamt… which was originally going to include an inscription on the back sleeve saying: “When I sleep with that picture beside me… I really think it’s you.”, which would explain the lyrics: “When I sleep with that framed picture of you beside my bed / Oh, it’s childish and it’s silly, but I think it’s you in my room, by the bed.”

The single’s inner sleeve was also going to feature a lyric from Well I Wonder, “Please keep me in mind”, so these may very well have been messages for Johnny.

Worthy of interest are also the parts about love at first sight and seeing each other with no clothes on.

Suedehead → the lyrics are about someone sticking around Morrissey even though they know it hurts him. Suedeheads were a subculture in early 1970’s England that split off from the skinheads and came to popular notice in a book by Richard Allen. Morrissey apparently read the book, but according to Len Brown’s Meetings with Morrissey interviews, the title has little to do with the subject matter of the song:

M: I did happen to read the book when it came out and I was quite interested in the whole Richard Allen cult. But really I just like the word ‘suedehead’."

LB: “So it’s not even based on an episode from Suedehead?”

M: “No, not really.”

LB: “And it’s not about anyone in particular?”

M: “Yes, it is, but I’d rather not give any addresses and phone numbers at this stage. But the most interesting nugget of information comes once again from Mozipedia, which says it may be worth taking into consideration a recollection from Johnny about a period during the latter half of The Smiths’ career when he decided to ‘get a motorbike and get a suedehead’. ‘That was my mantra for a while. Gotta get a suedehead! Gotta get a suedehead!’ […] ‘I think I may have brought that word into the vernacular, I might be wrong. But that’s what I did, got myself a motorbike and a suedehead haircut. To cloud further autobiographical analysis, Morrissey also said that he has never kept a diary, even though “I make so many records that in a peculiar way that becomes like a personal diary”. And as far as the repeated “It was a good lay” at the end, he said he just made it up (which I personally doubt, but I guess we’ll never know for sure).

Break Up The Family → I feel like the title is a metaphor for The Smiths splitting up.

“You say break up the family and let’s begin to live our lives”. It was Johnny who wanted to ‘take a break’ from the band, which Morrissey didn’t approve of, so this may very well be about that particular moment when Johnny told him he’d had enough.

There’s yet another reference to being driven home by someone: “Hailstones, driven home in his car- no breaks? I don’t mind.” Which reminds me of There Is A Light… “And if a double-decker bus crashes into us, to die by your side it’s such a heavenly way to die.”

I Don’t Mind If You Forget Me → when Morrissey started working on Viva Hate, one of the earliest songs he was working on was called I Don’t Want Us To Finish, with Us probably being him and Johnny. It’s said the song was later scrapped, but I feel like it may actually have been turned into this one instead.

In the lyrics, Morrissey is trying to convince himself that he doesn’t mind if the person he cares about the most ends up forgetting him, but clearly he does care, otherwise he wouldn’t have written an entire song about it.

“The pressure to change, to move on / Was strange and very strong / So this is why I tell you / I really do understand / Bye bye”.

I feel like this is another reference to Johnny’s departure, because it was him who wanted a change of direction for the band’s future, while Morrissey seemed to be happy for them to stay as they were.

Treat Me Like A Human Being → this was a demo which was abandoned and later released in 2012 on a Viva Hate reissue, taking the place as track 9 instead of The Ordinary Boys.

The lyrics are a plea by Morrissey for someone to acknowledge his feelings and have some compassion for him. The reason I’m including it in this list is because of the lyric: “Leave all your hate behind you”, which could be interpreted as a reference to the fact that, after The Smiths split up, Johnny had started bad-mouthing him in the press.

Worthy of interest is also: “Three words could change my life / Yet you treat me like you never care”. I wonder what those three words might be… “Stop being racist”, maybe?

Oh Well, I’ll Never Learn → Suedehead b-side, there’s not much to say about this one but I do find the lyrics “I found a fountain of youth / And I fell in / How could I ever win?” interesting, if anything because they make me think of the fact that Johnny, being four years younger than Morrissey, was the one who put The Smiths together. It’s also been mentioned how energetic he was, fully in contrast with Morrissey’s coy personality, and yet Johnny’s energy would prove infectious, providing him with an unexpected source of drive and creativity and making him feel rejuvenated, much like a fountain of youth.

Also, right at the beginning it says: “Looking up at the sign / It said: PLEASE KEEP AWAY / And so in I ran” which can be read in many ways, but would make perfect sense in the context of falling in love with someone you can’t have.

Bona Drag

He Knows I’d Love To See Him → the lyrics are about Morrissey wanting to rekindle his relationship with someone he hasn’t seen for quite some time. Even though he’s never admitted to it, I feel like this has to be about Johnny because of the line:

“’Cause when I lived in the arse of the world”. It’s common knowledge that Johnny was the one who first reached out to Morrissey about forming a band by showing up to his house and later, in an interview, he said that Johnny’s initiative probably saved his life.

Also, the lyric: “My name still conjures up deadly deeds / And a bad taste in the mouth” could be yet another reference to the fact that The Smiths’ split-up hadn’t been exactly amicable and Johnny was talking badly about him in the press. Still, even though Morrissey makes his feelings known right from the title (he wish he could see him and still wishes him happiness), the final: “He doesn’t know” suggests that the other person is not aware of Morrissey’s magnanimity.

Also, in an interview of the same period (1990), he was asked:

“If Johnny phoned and asked to work with you again, what would you say?” to which he replied: “It’s no secret I would be on the next bus to his house”. So, it seems like the song might have reflected his actual feelings.

Yes, I Am Blind → the reason I’m including this is because of the lyric: “Yes, I am blind / But I do see / Evil people prosper / Over the likes of you and me, always”. Which reminds me a lot of: “And people who are weaker than you and I / they take what they want from life” from A Rush And A Push… which I think was directed to Johnny as well.

Pretty interesting are also the lyrics: “Love’s young dream / I’m the one who shopped you / I’m the one who stopped you / ‘Cause in my sorry ways I love you” and: “Love’s young dream / Are you sorry for what you’re done? / Well, you’re not the only one / And in my sorry ways I love you”.

This sounds like ‘Love’s young dream’ was the one who made the first move towards Morrissey but was then pushed away by the man himself, maybe because he realized this person didn’t actually love him as much as he thought.

Also, that repeated: “And in my sorry ways I love you” reminds me a lot of that line in Speedway, “In my own strange way / I’ve always been true to you / In my own sick way / I’ll always stay true to you” (more on that later).

This is one of those songs that has no explicit references to Johnny or to events surrounding him, but it has such a feeling of longing to it, I can’t help but think it may have been written with him in mind.

Happy Lovers At Last United → Johnny and Angie split up for a brief period back in 1983, just before The Smiths were to go on tour in the USA for the first time, but got back together once the band were back in the UK. This song talks about Morrissey helping a couple of friends reuniting and then feeling sad because he feels like they don’t want him nor need him anymore.

Obviously I don’t know why or how Johnny and Angie actually got back together… according to The Severed Alliance, they had split up in the first place because Johnny had gotten closer to an ex of his and it was actually Joe Moss, the band’s first manager and Johnny’s friend, who suggested he and Angie should get married. Morrissey’s role in this whole thing, on the other hand, is never mentioned, so the only thing we can rely on are these lyrics.

Kill Uncle

Tony The Pony → This song is a pretty harsh condemnation of someone who lets himself being repeatedly taken advantage of by anyone and personally, I see it as the flipside of Angel Angel Down We Go Together. The reason being, they both deal with a similar theme, but in two completely different ways. While Angel Angel is sad but compassionate, this one is resentful and dripping with exasperation.

“Just don’t say I didn’t warn you / Always nagging big brother / He’s only looking out for you”. Being older than Johnny, Morrissey was the one who tried to refrain him from doing stuff he didn’t approve of (like working with anyone who wasn’t him).

“Tony the pony / So, that’s what they call you now? / When you’re free outside / So cold and hard and in control / And… there’s a free ride on Tony the pony”.

Again, Johnny was the one who left the band, who wanted a change of direction and who, right after The Smiths split up, started playing with loads of different people (Bryan Ferry, Talking Heads, The Pretenders, Bernard Sumner…) and that would make any control freak (such as Morrissey undoubtedly is) very bitter very quickly. He’s basically calling Johnny a (music) slut, who anyone can try and hire for a while.

“Oh, why do you always want to stop me / From doing the things in life that make me happy? / And when I’m outside with friends, laughing loudly / Why do you always want to stop me?” and immediately after: “Oh, I would never / I would never”.

This reads like a dialogue, with Tony the pony first asking Morrissey why he always has to spoil his fun and Morrissey replying that he would never dream of doing such a thing.

Right at the end though, the bitterness comes right through with: “I will never say I told you so / or how I knew that something bad would happen to you / I don’t want to say I told you so / oh, but Tony, I told you so!”.

I wish there were more specific references (like… what did happen to Tony that was so bad?), but I feel like my initial point still stands.

The Loop → Sing Your Life b-side, the lyrics are a plea for someone to call him if he needs him. “So one day, when you’re bored / By all means call / Because you can do / But you might not get through”. I find the last line particularly interesting because it reveals that Morrissey’s professed availability has an expire date after all.

As for the identity of this plea’s addressee, I’m just gonna quote Mozipedia:

“The singer’s short message to an old friend telling them ‘by all means call me’ and inevitably interpreted by Smiths romantics as being directed towards Marr.”

Apparently, Morrissey was especially proud of this song, even calling it his favourite at the time.

Your Arsenal

You’re Gonna Need Someone On Your Side → This is another one which I have doubts on (the lyrics are so vague they could be about anyone, really), but Verse 2 is the one I find the most interesting: “Someone kindly told me that you’d wasted eight of nine lives / Oh, give yourself a break before you break down / You’re gonna need someone on your side”.

Johnny was known to be a workaholic, even compromising his own health by devoting all of his time to any project he was working on. He also mentioned how alcohol and drugs became a problem for him in the 90s, how he used them to cope with stress, and by this time he was working with Bernard Sumner on Electronic, so my guess is that they were leading quite a hectic lifestyle. Considering him and Morrissey were still not talking to each other, it would make sense for Morrissey to know what he was up to through friends they had in common and if they had told him Johnny was still working himself to the point of exhaustion, it would make sense for him to get worried about him, hence this song, which is about being supportive through concern for someone.

The other interesting part is the ending: “And here I am! / Well, you don’t need to look so pleased”. It feels like Morrissey knows the other person wouldn’t necessarily want his support, even though that doesn’t stop him from providing it, hoping the other person might come around eventually.

Tomorrow → The reason I’m including it on this list is this part: “All I ask of you is one thing that you’ll never do / Would you put your arms around me? / I won’t tell anybody.” which, even though the connection is tenuous, reminds me of this bit from by Grand Central Station…

“I am lonely. I cannot be a female saint. I want the one I want. He is the one I picked out from the world. I picked him out in cold deliberation. But the passion was not cold. It kindled me. It kindled the world. Love, love, give my heart ease, put your arms round me, give my heart ease. Feel the little bastard.”

It could be about Johnny or it could be about someone else entirely. At this point, some time had passed since The Smiths’ demise and who knows what Morrissey had been exactly up to (and with whom)? The one thing I’m quite sure of is that, considering how much he took from it, Morrissey used By Grand Central Station… as a way to express and sublimate his conflicting feelings towards Johnny (I might make a separate, more in-depth analysis on that in the future).

Vauxhall and I (Vauxhall is both an area of London noted for its gay clubs AND a British car manufacturer, so it looks like Morrissey’s car kink is still alive and well).

Billy Budd → from Mozipedia: “Taking its title from the 1960 film Billy Budd, based upon the posthumously published novella of Moby Dick author Herman Melville, Morrissey uses the term as a playful nickname for a long-standing and long-suffering companion. As he describes, their relationship provokes public ridicule and discrimination, so much so that Morrissey comically volunteers to have his legs amputated as a sacrifice for Billy’s freedom. The elusive nature of the lyrics offers few clues as to the identity of ‘Billy Budd’ beyond the mention of ‘12 years on’. Since the song was released in 1994 (though recorded in 1993) the line was interpreted by many as a reference to Johnny Marr whom he ‘took up with’ 12 years earlier in 1982. This theory is somewhat compounded by the outrageously spooky coincidence that in 1888 Melville published a collection of poetry titled John Marr and Other Sailors. The song also includes what appears to be another fleeting citation from one of Morrissey’s favourite sources, Elizabeth Smart’s By Grand Central Station… ([‘they intercepted our glances because of] what was in our eyes’)”.

There’s also an audio floating around in which Morrissey changes the lyrics from “but now it’s 12 years on” to “now it’s 15 years on” in 1997, 15 years after he met Johnny.

As for the Melville references, I highly recommend you go and read his ‘John Marr’ poem in its entirety, but this is my favourite part:

- I yearn as ye. But rafts that strain,

Parted, shall they lock again?

Twined we were, entwined, then riven,

Ever to new embracements driven,

Shifting gulf-weed of the main!

And how if one here shift no more,

Lodged by the flinging surge ashore?

Nor less, as now, in eve's decline,

Your shadowy fellowship is mine.

Ye float around me, form and feature:--

Tattooings, ear-rings, love-locks curled;

Speedway → from Mozipedia: “The detail that Johnny Marr once worked at a speedway in his teens is enough to satisfy some theorists that the song is a coded address to the ex-Smiths guitarist, ignoring the fact that at the time of recording Morrissey and Marr were on cordial terms”.

Personally, I don’t agree with this (partial) dismissal. The fact that they were on good terms at the time doesn’t mean that everything between them had necessarily been solved.

I’d like to focus on this part, specifically: “I could have mentioned your name / I could have dragged you in / Guilt by implication, by association / I’ve always been true to you / In my own strange way / I’ve always been true to you / In my own sick way / I’ll always stay true to you”.

Let’s go back to Billy Budd for a moment: “I said, Billy Budd / I would happily lose both of my legs / Oh, if it meant you could be free”.

Free from what, exactly? From expectations? From life itself? Looks like Johnny/Billy Budd had a secret burden weighing down on him, and now onto Speedway: “I could have mentioned your name” in regards to what? “Guilt by implication, by association” so, the burden Johnny/Billy Budd carried was also shared by Morrissey? And what could be so heinous, so scandalous as to require this eternal silent loyalty? Could it be that the relationship between Johnny and Morrissey went deeper than everyone thought or liked to admit? Could it be that they shared a bond which wasn’t just professional or even friendly, but that bordered instead on all-consuming, romantic obsession?

He then says that, in his own “strange way”, he’s always been loyal to him. The way he sings it though, putting quite a bit of emphasis on these two specific words, makes me think he’s hinting to Strangeways Here We Come, which both him and Johnny claimed was their best album and also the last one they recorded together.

Talking about the song, he said: “I believe in my loyalty which is as developed as possible.” So at the end, when he goes:

“In my own sick way / I’ll always stay true to you” it looks like whatever happens, the secret they share is so big and important it has to stay hidden no matter what. Morrissey is reassuring him that, if it ever gets out, it won’t be because of him.

“All of the rumours keeping me grounded / I never said, I never said / That they were completely unfounded.”

“And all those lies, written lies, twisted lies / Well, they weren’t lies, they weren’t lies, they weren’t lies.”

According to Mozipedia: “It was only a decade later that Morrissey ended all further debate by admitting, somewhat flippantly, that the lyrics were ‘probably’ just his way of winding up his detractors at the time.”

We all know that Morrissey has been at the center of many a storm throughout his career, but what’s the oldest one, the one that has been the most recurring, the one most journalists seem to always come back to, in the end?

His sexuality. His sexual and romantic relationships (or lack thereof). His self-admitted celibacy, right at the beginning of his career, which immediately set him apart from the rest of his colleagues and sparked instant curiosity. The vagueness, the hints, the lack of evidence. Is he gay? Bisexual? Asexual? Or really just hopeless when it comes to human connection? When they don’t have a definite answer, some people invent it, even if it’s just to make things more interesting. So, there you have it. Journalists creating rumours out of thin air just to sell a few more papers. Journalists who encourage endless speculations on the most private aspects of an individual’s life. His lyrics are dissected, his friendships scrutinised just to find that final puzzle piece, the one which will make everyone go: “Ah, finally, there it is! I knew he was!”.

But more often than not, Morrissey ends up beating them at their same game. He muddies the waters, he hides his tracks. Many of the songs which people could argue are about Johnny are released as b-sides. Is this really a coincidence?

To me, this song represents closure. It’s Morrissey’s way of saying: ‘Look, I know we’ve been through a lot but, no matter what, I will protect you. I won’t rat you out’.

At the time, it looked like Morrissey had finally found love with Jake Walters, his driver, and I think most of this record and the stuff he wrote after is about him.

But if Johnny was his first real love, then this sounds like the final vent, the definite acknowledgment of what has been, before leaving the past behind for greener pastures.

You Are The Quarry

Never Played Symphonies → B-side of Irish Blood, English Heart, the lyrics are about Morrissey laying on his metaphorical deathbed and looking at all the people who cared about him, but he’s not able to see them because he’s focused on the Never Played Symphonies of the title, which are the people he didn’t get to be with.

“You were one, you meant to be one / And you jumped into my face and laughed / And kissed me on the cheek and then were gone forever… not quite”.

This is a bit of a reach, but there’s a gif floating around from an old movie of The Smiths backstage in Sheffield in 1984 where Johnny and Morrissey are looking at the camera, then Johnny leans into Morrissey as if he’s about to kiss him on the cheek, but Morrissey raises his hands and points at him, stopping him.

I don’t know for sure if he wrote this whole song with Johnny in mind, but that was the first thing I thought upon reading that line.

Also, that final “… not quite” becomes significant if you think about their relationship post-Smiths. They spent years not talking to each other, then they made up and were on good terms for a while, then there was the whole Joyce trial and they grew distant once again. But even if Johnny has been gone from Morrissey’s life for quite some time, he has never really gone, if you know what I mean. And he probably never will be, because their shared history is impossible to ignore.

The final part: “You were one, you knew you were one / And you slipped right through my fingers / No not literally but metaphorically / And now you’re all I see as the light fades.” makes me think that whatever happened between them, even if it was physical, was mostly felt on Morrissey’s part (it reminds me of that quote in his Autobiography, “It was probably nothing, but it felt like the world”).

The reason I think this is about Johnny is that “you’re all I see as the light fades”, as if to say: the light has finally gone out, and now it’s just you.

World Peace Is None Of Your Business

Forgive Someone → a bonus track on the deluxe edition, it sounds like Morrissey’s been reminiscing on past grievances.

“Betray you with a sword / I would slit my own throat first of all, I will”.

This reminds me of Speedway’s repeated declarations of eternal loyalty.

“The black peat of the hills / When I was still ill”.

This has to be a reference to The Smiths’ song Still Ill, even though “the black peat of the hills” also reminds me of These Things Take Time: “… and the hills are alive with celibate cries”. It’s like he’s thinking about his late adolescence, when he was lonely and depressed, before Johnny came to save him.

“And then recall if you can / How all this even began / Forgive someone”.

This looks like Morrissey is asking Johnny to think about how their legacy came to be and to forgive him for any mistakes he made.

“Shorts and supports and faulty shower heads / At track and field we dreamt of our beds / In the bleachers you sit with your legs spread, smiling / ‘Here’s one thing you’ll never have’”.

I feel like Morrissey’s past car kink has been replaced by a runner kink, especially considering the fact he later wrote List of the Lost, in which the main characters are track runners.

The final, repeated “Our truth will die with me” reminds me once again of Speedway’s ending: “In my own sick way, I’ll always stay true to you”.

In conclusion, whatever happened between Johnny and him will remain between the two of them, at least until Morrissey is alive.

#the smiths#morrissey#johnny marr#marrissey#this has been quite a ride my dudes#good luck to anyone who decides to read this

149 notes

·

View notes

Text

as we all know loki is a fan of art and literature. so here are some loki x bruce friendship headcanons related to that

while loki admires bruce’s brains (loki thinks everyone is stupid except for bruce), he feels sorry that bruce hasn’t got a phd in literature

bruce admits to him that he loves reading of course but he wasn’t really good at literature in school. essays were a nightmare. how can he explain why did the author use this literature device and not another? but yes, he loves reading for pleasure

you can say that bruce finds interesting stories and ideas in books while loki appreciates the beauty of the language, the aesthetics, the depth of the characters. and loki loves poetry too

but. DRAMA. loki LIVES for drama

while bruce doesn’t really enjoy is that much. he read some plays in school and that’s all. but of course he appreciates important playwrights

so loki decides to introduce bruce to asgardian writers. thor can discuss science with bruce, and loki wants to discuss art with him, can you blame him? at least to show him his favourite books and paintings. and music too. he really is curious what bruce will think of his favourite pieces of art. loki appreciates bruce’s mind enormously but he’s a bit nervous??? just a bit. because bruce doesn’t seem to be a fan of all that

so when bruce tells him that he loved the play loki told him to read, loki is happy. he asks bruce everything about that, what did he like what he didn’t like. then loki brings him another play. and another one. and then a novel. and then poems

loki spends a lot of time in the library now thinking about what bruce might like among all those books. he chooses very carefully

loki brings bruce to asgardian theatre and bruce loves everything about it

when bruce reads thor an asgardian poem in asgardian about love (bruce learns asgardian) thor is happy as never. not only because of the fact that bruce is reading a poem in his language, but also because he knows that it was loki who showed him this poem. who else would. but when he goes to loki to say that he’s touched enormously loki just says ‘whatever’. but inside loki’s happy. he loves this poem too.

then bruce decides to show earth’s literature to loki in return. loki is a bit confused because midgardian literature? really? is it as beautiful as asgardian? don’t think so

but then he reads shakespeare for the first time and.. oh boy.

oh boy

does he love shakespeare’s plays

bruce is catching on shakespeare too since he wants to talk about him with loki

and after many conversations with loki about shakespeare bruce finally understands why people love him so much. loki points out the beauty bruce never saw in those plays. loki says it’s all because you never really pay attention when you read it for the first time, but when you reread the plays you realise how perfectly they are written, how beautiful is the language

loki saw every version of hamlet by the way

they go to the opera house and loki falls in love with opera

and the ballet. he is smitten by the ballet, they don’t have it on asgard. he is fascinated by it. they visit bolshoi theatre

bruce’s goal now is to show to loki the best theatres on earth

and the thing he loves the most in this whole thing is loki’s reaction. he laughs, he admires, and he cries sometimes and bruce swears on his blood that he’s never gonna tell thor about it

bruce is still not an avid theatre goer inside, but he does this because he loves spending time with loki and he loves seeing loki being excited about art, he can listen to him talking about it all day. especially since loki makes such interesting points bruce would have never thought of. loki is truly happy when he sees a good piece of art and bruce is ready to do everything to make loki happy

do i need to mention how happy is thor about all this? he is so, so happy. at some point he starts to joke around that loki’s gonna steal his husband but loki replies with something like ‘heavens no. he doesn’t like opera that much. your influence by the way’

loki likes to quote lines from his favourite plays. loki would say something very beautiful and eloquent and thor would be like ‘what’ and bruce will just say ‘oscar wilde’

all in all, loki has now someone who can tolerate him being an art nerd. tolerate is not a very good word, because bruce genuinely loves that. he’s grateful to loki that he showed him the beauty of art. now he knows how he’s gonna spend his immortality and he’s very happy he has not only thor but also loki by his side

#loki#bruce banner#there are bits of#thorbruce#lokibruce#bruceloki#what is the tag for them#loki x bruce#bruce x loki#bruce banner headcanon

148 notes

·

View notes

Text

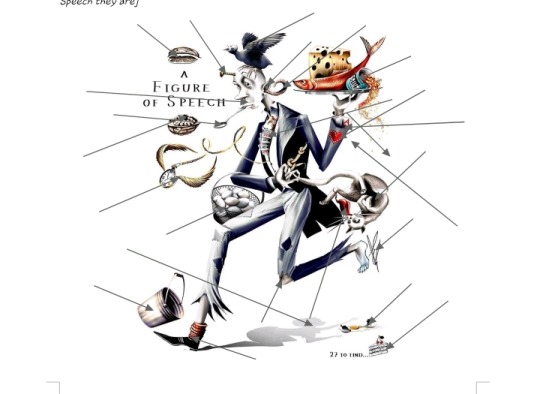

What is a Play

Extract from The Theory of the Theatre by Clayton Hamilton

A play is a story devised to be presented by actors on a stage before an audience.

This plain statement of fact affords an exceedingly simple definition of the drama,—a definition so simple indeed as to seem at the first glance easily obvious and therefore scarcely worthy of expression. But if we examine the statement thoroughly, phrase by phrase, we shall see that it sums up within itself the entire theory of the theatre, and that from this primary axiom we may deduce the whole practical philosophy of dramatic criticism.

It is unnecessary to linger long over an explanation of the word "story." A story is a representation of a series of events linked together by the law of cause and effect and marching forward toward a predestined culmination,—each event exhibiting imagined characters performing imagined acts in an appropriate imagined setting. This definition applies, of course, to the epic, the ballad, the novel, the short-story, and all other forms of narrative art, as well as to the drama.

But the phrase "devised to be presented" distinguishes the drama sharply from all other forms of narrative. In particular it must be noted that a play is not a story that is written to be read. By no means must the drama be considered primarily as a department of literature,—like the epic or the novel, for example. Rather, from the standpoint of the theatre, should literature be considered as only one of a multitude of means which the dramatist must employ to convey his story effectively to the audience. The great Greek dramatists needed a sense of sculpture as well as a sense of poetry; and in the contemporary theatre the playwright must manifest the imagination of the painter as well as the imagination of the man of letters. The appeal of a play is primarily visual rather than auditory. On the contemporary stage, characters properly costumed must be exhibited within a carefully designed and painted setting illuminated with appropriate effects of light and shadow; and the art of music is often called upon to render incidental aid to the general impression. The dramatist, therefore, must be endowed not only with the literary sense, but also with a clear eye for the graphic and plastic elements of pictorial effect, a sense of rhythm and of music, and a thorough knowledge of the art of acting. Since the dramatist must, at the same time and in the same work, harness and harmonise the methods of so many of the arts, it would be uncritical to centre studious consideration solely on his dialogue and to praise him or condemn him on the literary ground alone.

It is, of course, true that the very greatest plays have always been great literature as well as great drama. The purely literary element—the final touch of style in dialogue—is the only sure antidote against the opium of time. Now that Aeschylus is no longer performed as a playwright, we read him as a poet. But, on the other hand, we should remember that the main reason why he is no longer played is that his dramas do not fit the modern theatre,—an edifice totally different in size and shape and physical appointments from that in which his pieces were devised to be presented. In his own day he was not so much read as a poet as applauded in the theatre as a playwright; and properly to appreciate his dramatic, rather than his literary, appeal, we must reconstruct in our imagination the conditions of the theatre in his day. The point is that his plays, though planned primarily as drama, have since been shifted over, by many generations of critics and literary students, into the adjacent province of poetry; and this shift of the critical point of view, which has insured the immortality of Aeschylus, has been made possible only by the literary merit of his dialogue. When a play, owing to altered physical conditions, is tossed out of the theatre, it will find a haven in the closet only if it be greatly written. From this fact we may derive the practical maxim that though a skilful playwright need not write greatly in order to secure the plaudits of his own generation, he must cultivate a literary excellence if he wishes to be remembered by posterity.

This much must be admitted concerning the ultimate importance of the literary element in the drama. But on the other hand it must be granted that many plays that stand very high as drama do not fall within the range of literature. A typical example is the famous melodrama by Dennery entitled The Two Orphans. This play has deservedly held the stage for nearly a century, and bids fair still to be applauded after the youngest critic has died. It is undeniably a very good play. It tells a thrilling story in a series of carefully graded theatric situations. It presents nearly a dozen acting parts which, though scarcely real as characters, are yet drawn with sufficient fidelity to fact to allow the performers to produce a striking illusion of reality during the two hours' traffic of the stage. It is, to be sure—especially in the standard English translation—abominably written. One of the two orphans launches wide-eyed upon a soliloquy beginning, "Am I mad?... Do I dream?"; and such sentences as the following obtrude themselves upon the astounded ear,—"If you persist in persecuting me in this heartless manner, I shall inform the police." Nothing, surely, could be further from literature. Yet thrill after thrill is conveyed, by visual means, through situations artfully contrived; and in the sheer excitement of the moment, the audience is made incapable of noticing the pompous mediocrity of the lines.