#I used to really like him and read his literary criticism like crazy. but his autiobiography bored and annoyed me and now i just make a face

Note

Lolita hehehe

:) I’m so excited to read lolita its been on my tbr for ages. I think I’ll like it a lot

#unfortunately through the months nabokov and I have gone on a less than pleasant journey#I used to really like him and read his literary criticism like crazy. but his autiobiography bored and annoyed me and now i just make a face#when I see him. moral: never let the autobiography be the first thing of an author u read. *Bows thankyou#asks#eva tag

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Green Knight and Medieval Metatextuality: An Essay

Right, so. Finally watched it last night, and I’ve been thinking about it literally ever since, except for the part where I was asleep. As I said to fellow medievalist and admirer of Dev Patel @oldshrewsburyian, it’s possibly the most fascinating piece of medieval-inspired media that I’ve seen in ages, and how refreshing to have something in this genre that actually rewards critical thought and deep analysis, rather than me just fulminating fruitlessly about how popular media thinks that slapping blood, filth, and misogyny onto some swords and castles is “historically accurate.” I read a review of TGK somewhere that described it as the anti-Game of Thrones, and I’m inclined to think that’s accurate. I didn’t agree with all of the film’s tonal, thematic, or interpretative choices, but I found them consistently stylish, compelling, and subversive in ways both small and large, and I’m gonna have to write about it or I’ll go crazy. So. Brace yourselves.

(Note: My PhD is in medieval history, not medieval literature, and I haven’t worked on SGGK specifically, but I am familiar with it, its general cultural context, and the historical influences, images, and debates that both the poem and the film referenced and drew upon, so that’s where this meta is coming from.)

First, obviously, while the film is not a straight-up text-to-screen version of the poem (though it is by and large relatively faithful), it is a multi-layered meta-text that comments on the original Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, the archetypes of chivalric literature as a whole, modern expectations for medieval films, the hero’s journey, the requirements of being an “honorable knight,” and the nature of death, fate, magic, and religion, just to name a few. Given that the Arthurian legendarium, otherwise known as the Matter of Britain, was written and rewritten over several centuries by countless authors, drawing on and changing and hybridizing interpretations that sometimes challenged or outright contradicted earlier versions, it makes sense for the film to chart its own path and make its own adaptational decisions as part of this multivalent, multivocal literary canon. Sir Gawain himself is a canonically and textually inconsistent figure; in the movie, the characters merrily pronounce his name in several different ways, most notably as Sean Harris/King Arthur’s somewhat inexplicable “Garr-win.” He might be a man without a consistent identity, but that’s pointed out within the film itself. What has he done to define himself, aside from being the king’s nephew? Is his quixotic quest for the Green Knight actually going to resolve the question of his identity and his honor – and if so, is it even going to matter, given that successful completion of the “game” seemingly equates with death?

Likewise, as the anti-Game of Thrones, the film is deliberately and sometimes maddeningly non-commercial. For an adaptation coming from a studio known primarily for horror, it almost completely eschews the cliché that gory bloodshed equals authentic medievalism; the only graphic scene is the Green Knight’s original beheading. The violence is only hinted at, subtextual, suspenseful; it is kept out of sight, around the corner, never entirely played out or resolved. In other words, if anyone came in thinking that they were going to watch Dev Patel luridly swashbuckle his way through some CGI monsters like bad Beowulf adaptations of yore, they were swiftly disappointed. In fact, he seems to spend most of his time being wet, sad, and failing to meet the moment at hand (with a few important exceptions).

The film unhurriedly evokes a medieval setting that is both surreal and defiantly non-historical. We travel (in roughly chronological order) from Anglo-Saxon huts to Romanesque halls to high-Gothic cathedrals to Tudor villages and half-timbered houses, culminating in the eerie neo-Renaissance splendor of the Lord and Lady’s hall, before returning to the ancient trees of the Green Chapel and its immortal occupant: everything that has come before has now returned to dust. We have been removed even from imagined time and place and into a moment where it ceases to function altogether. We move forward, backward, and sideways, as Gawain experiences past, present, and future in unison. He is dislocated from his own sense of himself, just as we, the viewers, are dislocated from our sense of what is the “true” reality or filmic narrative; what we think is real turns out not to be the case at all. If, of course, such a thing even exists at all.

This visual evocation of the entire medieval era also creates a setting that, unlike GOT, takes pride in rejecting absolutely all political context or Machiavellian maneuvering. The film acknowledges its own cultural ubiquity and the question of whether we really need yet another King Arthur adaptation: none of the characters aside from Gawain himself are credited by name. We all know it’s Arthur, but he’s listed only as “king.” We know the spooky druid-like old man with the white beard is Merlin, but it’s never required to spell it out. The film gestures at our pre-existing understanding; it relies on us to fill in the gaps, cuing us to collaboratively produce the story with it, positioning us as listeners as if we were gathered to hear the original poem. Just like fanfiction, it knows that it doesn’t need to waste time introducing every single character or filling in ultimately unnecessary background knowledge, when the audience can be relied upon to bring their own.

As for that, the film explicitly frames itself as a “filmed adaptation of the chivalric romance” in its opening credits, and continues to play with textual referents and cues throughout: telling us where we are, what’s happening, or what’s coming next, rather like the rubrics or headings within a medieval manuscript. As noted, its historical/architectural references span the entire medieval European world, as does its costume design. I was particularly struck by the fact that Arthur and Guinevere’s crowns resemble those from illuminated monastic manuscripts or Eastern Orthodox iconography: they are both crown and halo, they confer an air of both secular kingship and religious sanctity. The question in the film’s imagined epilogue thus becomes one familiar to Shakespeare’s Henry V: heavy is the head that wears the crown. Does Gawain want to earn his uncle’s crown, take over his place as king, bear the fate of Camelot, become a great ruler, a husband and father in ways that even Arthur never did, only to see it all brought to dust by his cowardice, his reliance on unscrupulous sorcery, and his unfulfilled promise to the Green Knight? Is it better to have that entire life and then lose it, or to make the right choice now, even if it means death?

Likewise, Arthur’s kingly mantle is Byzantine in inspiration, as is the icon of the Virgin Mary-as-Theotokos painted on Gawain’s shield (which we see broken apart during the attack by the scavengers). The film only glances at its religious themes rather than harping on them explicitly; we do have the cliché scene of the male churchmen praying for Gawain’s safety, opposite Gawain’s mother and her female attendants working witchcraft to protect him. (When oh when will I get my film that treats medieval magic and medieval religion as the complementary and co-existing epistemological systems that they were, rather than portraying them as diametrically binary and disparagingly gendered opposites?) But despite the interim setbacks borne from the failure of Christian icons, the overall resolution of the film could serve as the culmination of a medieval Christian morality tale: Gawain can buy himself a great future in the short term if he relies on the protection of the enchanted green belt to avoid the Green Knight’s killing stroke, but then he will have to watch it all crumble until he is sitting alone in his own hall, his children dead and his kingdom destroyed, as a headless corpse who only now has been brave enough to accept his proper fate. By removing the belt from his person in the film’s Inception-like final scene, he relinquishes the taint of black magic and regains his religious honor, even at the likely cost of death. That, the medieval Christian morality tale would agree, is the correct course of action.

Gawain’s encounter with St. Winifred likewise presents a more subtle vision of medieval Christianity. Winifred was an eighth-century Welsh saint known for being beheaded, after which (by the power of another saint) her head was miraculously restored to her body and she went on to live a long and holy life. It doesn’t quite work that way in TGK. (St Winifred’s Well is mentioned in the original SGGK, but as far as I recall, Gawain doesn’t meet the saint in person.) In the film, Gawain encounters Winifred’s lifelike apparition, who begs him to dive into the mere and retrieve her head (despite appearances, she warns him, it is not attached to her body). This fits into the pattern of medieval ghost stories, where the dead often return to entreat the living to help them finish their business; they must be heeded, but when they are encountered in places they shouldn’t be, they must be put back into their proper physical space and reminded of their real fate. Gawain doesn’t follow William of Newburgh’s practical recommendation to just fetch some brawny young men with shovels to beat the wandering corpse back into its grave. Instead, in one of his few moments of unqualified heroism, he dives into the dark water and retrieves Winifred’s skull from the bottom of the lake. Then when he returns to the house, he finds the rest of her skeleton lying in the bed where he was earlier sleeping, and carefully reunites the skull with its body, finally allowing it to rest in peace.

However, Gawain’s involvement with Winifred doesn’t end there. The fox that he sees on the bank after emerging with her skull, who then accompanies him for the rest of the film, is strongly implied to be her spirit, or at least a companion that she has sent for him. Gawain has handled a saint’s holy bones; her relics, which were well known to grant protection in the medieval world. He has done the saint a service, and in return, she extends her favor to him. At the end of the film, the fox finally speaks in a human voice, warning him not to proceed to the fateful final encounter with the Green Knight; it will mean his death. The symbolism of having a beheaded saint serve as Gawain’s guide and protector is obvious, since it is the fate that may or may not lie in store for him. As I said, the ending is Inception-like in that it steadfastly refuses to tell you if the hero is alive (or will live) or dead (or will die). In the original SGGK, of course, the Green Knight and the Lord turn out to be the same person, Gawain survives, it was all just a test of chivalric will and honor, and a trap put together by Morgan Le Fay in an attempt to frighten Guinevere. It’s essentially able to be laughed off: a game, an adventure, not real. TGK takes this paradigm and flips it (to speak…) on its head.

Gawain’s rescue of Winifred’s head also rewards him in more immediate terms: his/the Green Knight’s axe, stolen by the scavengers, is miraculously restored to him in her cottage, immediately and concretely demonstrating the virtue of his actions. This is one of the points where the film most stubbornly resists modern storytelling conventions: it simply refuses to add in any kind of “rational” or “empirical” explanation of how else it got there, aside from the grace and intercession of the saint. This is indeed how it works in medieval hagiography: things simply reappear, are returned, reattached, repaired, made whole again, and Gawain’s lost weapon is thus restored, symbolizing that he has passed the test and is worthy to continue with the quest. The film’s narrative is not modernizing its underlying medieval logic here, and it doesn’t particularly care if a modern audience finds it “convincing” or not. As noted, the film never makes any attempt to temporalize or localize itself; it exists in a determinedly surrealist and ahistorical landscape, where naked female giants who look suspiciously like Tilda Swinton roam across the wild with no necessary explanation. While this might be frustrating for some people, I actually found it a huge relief that a clearly fantastic and fictional literary adaptation was not acting like it was qualified to teach “real history” to its audience. Nobody would come out of TGK thinking that they had seen the “actual” medieval world, and since we have enough of a problem with that sort of thing thanks to GOT, I for one welcome the creation of a medieval imaginative space that embraces its eccentric and unrealistic elements, rather than trying to fit them into the Real Life box.

This plays into the fact that the film, like a reused medieval manuscript containing more than one text, is a palimpsest: for one, it audaciously rewrites the entire Arthurian canon in the wordless vision of Gawain’s life after escaping the Green Knight (I could write another meta on that dream-epilogue alone). It moves fluidly through time and creates alternate universes in at least two major points: one, the scene where Gawain is tied up and abandoned by the scavengers and that long circling shot reveals his skeletal corpse rotting on the sward, only to return to our original universe as Gawain decides that he doesn’t want that fate, and two, Gawain as King. In this alternate ending, Arthur doesn’t die in battle with Mordred, but peaceably in bed, having anointed his worthy nephew as his heir. Gawain becomes king, has children, gets married, governs Camelot, becomes a ruler surpassing even Arthur, but then watches his son get killed in battle, his subjects turn on him, and his family vanish into the dust of his broken hall before he himself, in despair, pulls the enchanted scarf out of his clothing and succumbs to his fate.

In this version, Gawain takes on the responsibility for the fall of Camelot, not Arthur. This is the hero’s burden, but he’s obtained it dishonorably, by cheating. It is a vivid but mimetic future which Gawain (to all appearances) ultimately rejects, returning the film to the realm of traditional Arthurian canon – but not quite. After all, if Gawain does get beheaded after that final fade to black, it would represent a significant alteration from the poem and the character’s usual arc. Are we back in traditional canon or aren’t we? Did Gawain reject that future or didn’t he? Do all these alterities still exist within the visual medium of the meta-text, and have any of them been definitely foreclosed?

Furthermore, the film interrogates itself and its own tropes in explicit and overt ways. In Gawain’s conversation with the Lord, the Lord poses the question that many members of the audience might have: is Gawain going to carry out this potentially pointless and suicidal quest and then be an honorable hero, just like that? What is he actually getting by staggering through assorted Irish bogs and seeming to reject, rather than embrace, the paradigms of a proper quest and that of an honorable knight? He lies about being a knight to the scavengers, clearly out of fear, and ends up cravenly bound and robbed rather than fighting back. He denies knowing anything about love to the Lady (played by Alicia Vikander, who also plays his lover at the start of the film with a decidedly ropey Yorkshire accent, sorry to say). He seems to shrink from the responsibility thrust on him, rather than rise to meet it (his only honorable act, retrieving Winifred’s head, is discussed above) and yet here he still is, plugging away. Why is he doing this? What does he really stand to gain, other than accepting a choice and its consequences (somewhat?) The film raises these questions, but it has no plans to answer them. It’s going to leave you to think about them for yourself, and it isn’t going to spoon-feed you any ultimate moral or neat resolution. In this interchange, it’s easy to see both the echoes of a formal dialogue between two speakers (a favored medieval didactic tactic) and the broader purpose of chivalric literature: to interrogate what it actually means to be a knight, how personal honor is generated, acquired, and increased, and whether engaging in these pointless and bloody “war games” is actually any kind of real path to lasting glory.

The film’s treatment of race, gender, and queerness obviously also merits comment. By casting Dev Patel, an Indian-born actor, as an Arthurian hero, the film is… actually being quite accurate to the original legends, doubtless much to the disappointment of assorted internet racists. The thirteenth-century Arthurian romance Parzival (Percival) by the German poet Wolfram von Eschenbach notably features the character of Percival’s mixed-race half-brother, Feirefiz, son of their father by his first marriage to a Muslim princess. Feirefiz is just as heroic as Percival (Gawaine, for the record, also plays a major role in the story) and assists in the quest for the Holy Grail, though it takes his conversion to Christianity for him to properly behold it.

By introducing Patel (and Sarita Chowdhury as Morgause) to the visual representation of Arthuriana, the film quietly does away with the “white Middle Ages” cliché that I have complained about ad nauseam; we see background Asian and black members of Camelot, who just exist there without having to conjure up some complicated rationale to explain their presence. The Lady also uses a camera obscura to make Gawain’s portrait. Contrary to those who might howl about anachronism, this technique was known in China as early as the fourth century BCE and the tenth/eleventh century Islamic scholar Ibn al-Haytham was probably the best-known medieval authority to write on it extensively; Latin translations of his work inspired European scientists from Roger Bacon to Leonardo da Vinci. Aside from the symbolism of an upside-down Gawain (and when he sees the portrait again during the ‘fall of Camelot’, it is right-side-up, representing that Gawain himself is in an upside-down world), this presents a subtle challenge to the prevailing Eurocentric imagination of the medieval world, and draws on other global influences.

As for gender, we have briefly touched on it above; in the original SGGK, Gawain’s entire journey is revealed to be just a cruel trick of Morgan Le Fay, simply trying to destabilize Arthur’s court and upset his queen. (Morgan is the old blindfolded woman who appears in the Lord and Lady’s castle and briefly approaches Gawain, but her identity is never explicitly spelled out.) This is, obviously, an implicitly misogynistic setup: an evil woman plays a trick on honorable men for the purpose of upsetting another woman, the honorable men overcome it, the hero survives, and everyone presumably lives happily ever after (at least until Mordred arrives).

Instead, by plunging the outcome into doubt and the hero into a much darker and more fallible moral universe, TGK shifts the blame for Gawain’s adventure and ultimate fate from Morgan to Gawain himself. Likewise, Guinevere is not the passive recipient of an evil deception but in a way, the catalyst for the whole thing. She breaks the seal on the Green Knight’s message with a weighty snap; she becomes the oracle who reads it out, she is alarming rather than alarmed, she disrupts the complacency of the court and silently shows up all the other knights who refuse to step forward and answer the Green Knight’s challenge. Gawain is not given the ontological reassurance that it’s just a practical joke and he’s going to be fine (and thanks to the unresolved ending, neither are we). The film instead takes the concept at face value in order to push the envelope and ask the simple question: if a man was going to be actually-for-real beheaded in a year, why would he set out on a suicidal quest? Would you, in Gawain’s place, make the same decision to cast aside the enchanted belt and accept your fate? Has he made his name, will he be remembered well? What is his legacy?

Indeed, if there is any hint of feminine connivance and manipulation, it arrives in the form of the implication that Gawain’s mother has deliberately summoned the Green Knight to test her son, prove his worth, and position him as his childless uncle’s heir; she gives him the protective belt to make sure he won’t actually die, and her intention all along was for the future shown in the epilogue to truly play out (minus the collapse of Camelot). Only Gawain loses the belt thanks to his cowardice in the encounter with the scavengers, regains it in a somewhat underhanded and morally questionable way when the Lady is attempting to seduce him, and by ultimately rejecting it altogether and submitting to his uncertain fate, totally mucks up his mother’s painstaking dynastic plans for his future. In this reading, Gawain could be king, and his mother’s efforts are meant to achieve that goal, rather than thwart it. He is thus required to shoulder his own responsibility for this outcome, rather than conveniently pawning it off on an “evil woman,” and by extension, the film asks the question: What would the world be like if men, especially those who make war on others as a way of life, were actually forced to face the consequences of their reckless and violent actions? Is it actually a “game” in any sense of the word, especially when chivalric literature is constantly preoccupied with the question of how much glorious violence is too much glorious violence? If you structure social prestige for the king and the noble male elite entirely around winning battles and existing in a state of perpetual war, when does that begin to backfire and devour the knightly class – and the rest of society – instead?

This leads into the central theme of Gawain’s relationships with the Lord and Lady, and how they’re treated in the film. The poem has been repeatedly studied in terms of its latent (and sometimes… less than latent) queer subtext: when the Lord asks Gawain to pay back to him whatever he should receive from his wife, does he already know what this involves; i.e. a physical and romantic encounter? When the Lady gives kisses to Gawain, which he is then obliged to return to the Lord as a condition of the agreement, is this all part of a dastardly plot to seduce him into a kinky green-themed threesome with a probably-not-human married couple looking to spice up their sex life? Why do we read the Lady’s kisses to Gawain as romantic but Gawain’s kisses to the Lord as filial, fraternal, or the standard “kiss of peace” exchanged between a liege lord and his vassal? Is Gawain simply being a dutiful guest by honoring the bargain with his host, actually just kissing the Lady again via the proxy of her husband, or somewhat more into this whole thing with the Lord than he (or the poet) would like to admit? Is the homosocial turning homoerotic, and how is Gawain going to navigate this tension and temptation?

If the question is never resolved: well, welcome to one of the central medieval anxieties about chivalry, knighthood, and male bonds! As I have written about before, medieval society needed to simultaneously exalt this as the most honored and noble form of love, and make sure it didn’t accidentally turn sexual (once again: how much male love is too much male love?). Does the poem raise the possibility of serious disruption to the dominant heteronormative paradigm, only to solve the problem by interpreting the Gawain/Lady male/female kisses as romantic and sexual and the Gawain/Lord male/male kisses as chaste and formal? In other words, acknowledging the underlying anxiety of possible homoeroticism but ultimately reasserting the heterosexual norm? The answer: Probably?!?! Maybe?!?! Hell if we know??! To say the least, this has been argued over to no end, and if you locked a lot of medieval history/literature scholars into a room and told them that they couldn’t come out until they decided on one clear answer, they would be in there for a very long time. The poem seemingly invokes the possibility of a queer reading only to reject it – but once again, as in the question of which canon we end up in at the film’s end, does it?

In some lights, the film’s treatment of this potential queer reading comes off like a cop-out: there is only one kiss between Gawain and the Lord, and it is something that the Lord has to initiate after Gawain has already fled the hall. Gawain himself appears to reject it; he tells the Lord to let go of him and runs off into the wilderness, rather than deal with or accept whatever has been suggested to him. However, this fits with film!Gawain’s pattern of rejecting that which fundamentally makes him who he is; like Peter in the Bible, he has now denied the truth three times. With the scavengers he denies being a knight; with the Lady he denies knowing about courtly love; with the Lord he denies the central bond of brotherhood with his fellows, whether homosocial or homoerotic in nature. I would go so far as to argue that if Gawain does die at the end of the film, it is this rejected kiss which truly seals his fate. In the poem, the Lord and the Green Knight are revealed to be the same person; in the film, it’s not clear if that’s the case, or they are separate characters, even if thematically interrelated. If we assume, however, that the Lord is in fact still the human form of the Green Knight, then Gawain has rejected both his kiss of peace (the standard gesture of protection offered from lord to vassal) and any deeper emotional bond that it can be read to signify. The Green Knight could decide to spare Gawain in recognition of the courage he has shown in relinquishing the enchanted belt – or he could just as easily decide to kill him, which he is legally free to do since Gawain has symbolically rejected the offer of brotherhood, vassalage, or knight-bonding by his unwise denial of the Lord’s freely given kiss. Once again, the film raises the overall thematic and moral question and then doesn’t give one straight (ahem) answer. As with the medieval anxieties and chivalric texts that it is based on, it invokes the specter of queerness and then doesn’t neatly resolve it. As a modern audience, we find this unsatisfying, but once again, the film is refusing to conform to our expectations.

As has been said before, there is so much kissing between men in medieval contexts, both ceremonial and otherwise, that we’re left to wonder: “is it gay or is it feudalism?” Is there an overtly erotic element in Gawain and the Green Knight’s mutual “beheading” of each other (especially since in the original version, this frees the Lord from his curse, functioning like a true love’s kiss in a fairytale). While it is certainly possible to argue that the film has “straightwashed” its subject material by removing the entire sequence of kisses between Gawain and the Lord and the unresolved motives for their existence, it is a fairly accurate, if condensed, representation of the anxieties around medieval knightly bonds and whether, as Carolyn Dinshaw put it, a (male/male) “kiss is just a kiss.” After all, the kiss between Gawain and the Lady is uncomplicatedly read as sexual/romantic, and that context doesn’t go away when Gawain is kissing the Lord instead. Just as with its multiple futurities, the film leaves the question open-ended. Is it that third and final denial that seals Gawain’s fate, and if so, is it asking us to reflect on why, specifically, he does so?

The film could play with both this question and its overall tone quite a bit more: it sometimes comes off as a grim, wooden, over-directed Shakespearean tragedy, rather than incorporating the lively and irreverent tone that the poem often takes. It’s almost totally devoid of humor, which is unfortunate, and the Grim Middle Ages aesthetic is in definite evidence. Nonetheless, because of the comprehensive de-historicizing and the obvious lack of effort to claim the film as any sort of authentic representation of the medieval past, it works. We are not meant to understand this as a historical document, and so we have to treat it on its terms, by its own logic, and by its own frames of reference. In some ways, its consistent opacity and its refusal to abide by modern rules and common narrative conventions is deliberately meant to challenge us: as before, when we recognize Arthur, Merlin, the Round Table, and the other stock characters because we know them already and not because the film tells us so, we have to fill in the gaps ourselves. We are watching the film not because it tells us a simple adventure story – there is, as noted, shockingly little action overall – but because we have to piece together the metatext independently and ponder the philosophical questions that it leaves us with. What conclusion do we reach? What canon do we settle in? What future or resolution is ultimately made real? That, the film says, it can’t decide for us. As ever, it is up to future generations to carry on the story, and decide how, if at all, it is going to survive.

(And to close, I desperately want them to make my much-coveted Bisclavret adaptation now in more or less the same style, albeit with some tweaks. Please.)

Further Reading

Ailes, Marianne J. ‘The Medieval Male Couple and the Language of Homosociality’, in Masculinity in Medieval Europe, ed. by Dawn M. Hadley (Harlow: Longman, 1999), pp. 214–37.

Ashton, Gail. ‘The Perverse Dynamics of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight’, Arthuriana 15 (2005), 51–74.

Boyd, David L. ‘Sodomy, Misogyny, and Displacement: Occluding Queer Desire in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight’, Arthuriana 8 (1998), 77–113.

Busse, Peter. ‘The Poet as Spouse of his Patron: Homoerotic Love in Medieval Welsh and Irish Poetry?’, Studi Celtici 2 (2003), 175–92.

Dinshaw, Carolyn. ‘A Kiss Is Just a Kiss: Heterosexuality and Its Consolations in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight’, Diacritics 24 (1994), 205–226.

Kocher, Suzanne. ‘Gay Knights in Medieval French Fiction: Constructs of Queerness and Non-Transgression’, Mediaevalia 29 (2008), 51–66.

Karras, Ruth Mazo. ‘Knighthood, Compulsory Heterosexuality, and Sodomy’ in The Boswell Thesis: Essays on Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality, ed. Matthew Kuefler (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006), pp. 273–86.

Kuefler, Matthew. ‘Male Friendship and the Suspicion of Sodomy in Twelfth-Century France’, in The Boswell Thesis: Essays on Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality, ed. Matthew Kuefler (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006), pp. 179–214.

McVitty, E. Amanda, ‘False Knights and True Men: Contesting Chivalric Masculinity in English Treason Trials, 1388–1415,’ Journal of Medieval History 40 (2014), 458–77.

Mieszkowski, Gretchen. ‘The Prose Lancelot's Galehot, Malory's Lavain, and the Queering of Late Medieval Literature’, Arthuriana 5 (1995), 21–51.

Moss, Rachel E. ‘ “And much more I am soryat for my good knyghts’ ”: Fainting, Homosociality, and Elite Male Culture in Middle English Romance’, Historical Reflections / Réflexions historiques 42 (2016), 101–13.

Zeikowitz, Richard E. ‘Befriending the Medieval Queer: A Pedagogy for Literature Classes’, College English 65 (2002), 67–80.

#the green knight#the green knight meta#sir gawain and the green knight#medieval literature#medieval history#this meta is goddamn 5.2k words#and has its own reading list#i uh#said i had a lot of thoughts?

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

That time you and your demon boyfriend went viral

hi yes hello obey me fandom!! my name is Gabbi and i have never played a single second of the actual game but i have read enough fanon content for the past year to have this idea swimming around in my head and now i am finally letting this accursed thing out of my brain and putting it in yours

also i’m only doing the brothers because any more than that and i’d have an aneurysm probably. oh and shoutout to @obeythebutler and @beels-burger-babe for inspiring me with their works to feel brave enough to write for this fandom

Lucifer:

You and Lucifer go viral on Asmo’s Devilgram story!

You’re in the kitchen helping Asmo with dinner duty and singing along to one of your playlists of human realm music that you like to show him.

Asmo starts filming your cute little dance while you stir the pot on the stove because you are just adorable!

About ten seconds into him filming, Lucifer appears in the doorway with quite the stern look on his face. You know, the one that comes right before a “MAMMOOOOOON” and strikes fear into the heart of all those with functioning eardrums. That one.

He opens his mouth, presumably to tell y’all to shut the fuck up, but then there’s a lull in the music and the eldest can hear your voice ever so slightly above the song’s vocalist and he freezes.

Man stops in his tracks like someone just smacked him in the face with a midair volleyball.

Asmo can be heard stifling a laugh behind his phone.

Lucifer’s face gets so soft and he almost, almost, loosens his metal-rod-through-the-ass posture before you notice him and give a little wave and ask if you and Asmo were being too loud like the considerate darling you are.

Lucifer clears and his throat and says something like, “No, you aren’t. I was just coming to check on how dinner is coming along,” and leaves, after which Asmo immediately presses the post button.

Screenshots of Lucifer’s heart eyes for you go absolutely viral because every demon on Devilgram goes absolutely feral for seeing the eldest demon brother lose his dignified composure. It becomes a meme template. “Get you someone who looks at you like Lucifer looks at MC” and “me at the delivery demon when he shows up with my spicy bat wings” posts become commonplace. (Asmo thinks the memes are totally worth getting strung up with Mammon for laughing at them.)

Mammon:

Much like Lucifer, you and Mammon end up going viral off Asmo’s Devilgram. (Noticing a pattern here?)

He pulls a silly prank on your asses and honestly I don’t know how you fell for it. But hey, they say “idiots in love” for a reason, so...

You and Asmo are sitting in the common room of the House of Lamentation just chillin. Well, he’s chillin, you’re on the floor studying for an upcoming exam.

The video starts in the middle of a conversation you and the avatar of lust were having.

“No, Asmo,” you say. “Mammon and I don’t use pet names for each other.” Now that’s just a darn lie, and every demon and crow within ten miles of Mammon and you together knows it.

“Really? I find that very hard to believe, MC.~”

You sigh in response to Asmo’s teasing. “Okay, he has a lot for me but I’m just not much of a pet name person, y’know?” The rest of the exchange goes like this:

“Oh, I totally get it.” *pause* “Hey MC, what do human world bees make again?”

“Honey.”

Cue a sheepish Mammon sticking his head in the doorway at the bluntness of your tone when you answered Asmo.

“Yeah, babe?” he looks like a puppy left on the side of a highway oh my god hUG HIM-

Asmo turns the camera back to his smug ass face and in the background you can be heard tripping on the damn carpet trying to get up and hug your mans. (”MAMMON GET OVER HERE SO I CAN HUG YOU” “W-WHAT? I THOUGHT YA WERE MAD AT ME?!?!?!?!”)

Leviathan:

Streamer Levi? Streamer Levi.

You guys go viral the first time you make an appearance on one of Levi’s weekly (insert cool Devildom streaming service name here) streams.

It’s completely unintentional. You had been asking him for weeks to play with him on there, but he’s the avatar of envy after all. He doesn’t like sharing his partner, even if it’s with random strangers who have no real access to you.

However, he has his stream on a Thursday instead of a Friday one week, and you come into his room carrying dinner because 1) You didn’t realize he was streaming and 2) No matter what he was doing, the boy needed to eat. It wasn’t unusual for you to bring him dinner, so you had no idea why he was blushing and stammering even more than usual this time in particular. Boy was speaking in beached whale trying to tell you what was wrong.

Then you notice his screen. Oh! “Hi chat!” You wave, setting Levi’s food down on his desk in front of his keyboard. “M-MC!” He full-on whines, slamming a hand over his mouth afterwards when he remembers his viewers could hear that.

Honestly, they’d meme the fuck out of him if it weren’t for the fact that they are FINALLY SEEING HIS HENRY!!! THE MYSTERIOUS MC!!!

Chat is bombarding you with questions while you make Levi eat dinner. And by make him eat dinner, I mean literally feeding this man forkfuls/spoonfuls while he games because you love how flustered he gets when you do that.

Does it impact his score? Absolutely. Does he care? Not really when you’re pampering him like that.

You start answering chat’s questions about you while he’s chewing so he can’t tell you to stop LMAO-

You’re a natural on stream. The VOD becomes the most popular on Levi’s account in a matter of hours and soon cute highlights compilations of you and him on that stream start making the rounds on Devildom Twitter.

Satan:

There was buildup to Satan going viral, similar to Levi in a way.

Satan does have a Devilgram, but it’s basically a white woman’s Instagram with added book reviews for variety. Unless you’re a reader his account is pretty boring: candles, books, fireplaces, and cats.

However, after you two started reading together fairly often he began posting pictures of your legs draped over his while you sat together. They’d always be captioned with vague ass pretentious literary criticism.

This goes on for months, and he gains a lot of (horny) followers after the leg pics start up. He doesn’t really get why but you both joke that it’s because you have some damn nice legs and I mean neither of you are complaining about the new following.

You two go viral when he finally shows your face, entirely by accident.

The post is a video, which is already strange for him and grabs attention. In it, you’re scoffing and reading an excerpt of a book, mocking its understanding of female anatomy.

“I’m quoting here, Satan: ‘her breasts bouncing around like giant pacmen.’ I’M SORRY?? THAT ISN’T HOW BOOBS WORK SIR. WHY ARE MEN ALLOWED TO WRITE?”

(fun fact that is a very real quote from a very real book I really read last month pls save me)

Originally the camera is focused on your body, with your head out of frame to protect your privacy, but your righteous anger made Satan laugh. Like, a real laugh. The one that makes you and everyone in earshot wonder if he truly was never an angel cause he sure as hell laughs like one but anyway-

When he threw his head back, his DDD angled up just a tad without him noticing, and your face was in view for like .2 seconds. Screenshots of it are making the rounds on Devilgram almost immediately: FINALLY THE LEGS’ OWNER HAS BEEN FOUND.

Satan apologizes profusely but you honestly find it funny and you two opt to just start taking selfies while reading with both of your faces in them from now on.

Asmodeus:

I’m gonna be real with you: you and Asmo go viral all the time. Pretty much everything Asmo posts can be considered viral because of his social media following and his status as one of the seven avatars of sin.

However, there are some fairly cute highlights to be pointed out among the times you were both featured in a post that blew up.

Your favorite is probably that time Asmo livestreamed on of you guys’ ‘Nail Nites,’ as you call them.

You’re both on the floor, doing your nails and kicking your feet back and forth while talking to chat. A lot of the questions are about your relationship, and there’s a lot of flirting back and forth between the two of you.

A particular clip of the stream does blow the fuck up on Devilgram, though, when someone screen records it and posts it with a bunch of heart emojis edited over it.

“’What colors do you think best describe each other?’ Ooo, that’s a good one, chat!” Asmo claps his hands together excitedly, making sure to be careful of his nails.

Pretty much everyone expected you to say pink, but you surprised both your boyfriend and your viewers when, after a pensive few moments, you replied with “Hmm...probably yellow or orange.”

“Can I ask why, darling?” Asmo tilts his head in confusion. I mean, yeah, those colors look good on him, but he doesn’t wear them often so he’s wondering about your thought process.

“Well, in the human world those colors often represent happiness, optimism, and positivity. You’re always the cheerful presence I need in my life when things get hard, so you have the vibe of those colors.”

Asmo proceeds to burst into tears and hug you, messing up both of your nails and prolonging the stream since you both have to start over. But neither of you particularly care.

Fun fact: Asmo has the clip that demon made of that portion of the stream saved on his DDD and watches it whenever he feels sad.

Beelzebub:

Beel and you probably go the most viral out of everybody. Like this moment is an entire phenomenon across the Devildom internet.

It’s a video, or well, multiple videos, taken at the end of a Fangol game that Beel’s team had just won. Everyone is cheering and going crazy, yourself included, and you just really wanted to congratulate your boyfriend.

So, like the rational person you are, you elect to climb up onto the railing of the bleachers and wave to get his attention.

You were absolutely fine up there, and sat all comfortably motioning Beel over to you. He notices, of course, and jogs over, standing right beneath you and looking up. (Back where you were sitting, Mammon is screeching like a hyena in heat and Belphie, who is laying down, has one eye open to glare at him. The youngest knows Beel would never let you hurt yourself; you’re fine.)

A bunch of assorted demons at the game has started filming while you were sat atop the railing since you were rather noticeable. Therefore, there’s a shit ton of different angles of the adorable events that follow:

You slide off the railing, landing right in Beel’s waiting arms bridal style. You’ve got this brilliant smile on your face as you pull his helmet off. None of the DDDs filming can hear it over the crowd noise, but Beel asks you why you just went through all that trouble and you tell him it’s because you wanted to tell him how proud you are.

Soft boy’s chest puffs up and he smiles this big cheesy smile at you reach up to run a hand through his hair. You feel him practically purr at the contact, and with a laugh you pull him in and plant a big ole smooch on him.

The crowd, at least those of them that can see, scream. Everyone is running high on adrenaline and happy emotions; something that cute causes a ruckus!! When you pull away Beel proceeds to put you on his shoulders and you celebrate with him and the rest of his team.

The videos of you two being adorable go completely viral and there are some threads dedicated to stockpiling every single angle taken of the event. Beel is completely oblivious to the attention but you have a lot of them saved on your DDD.

Belphegor:

If you think Belphegor has any sort of social media presence whatsoever then you are sorely mistaken. (Well okay he actually does run some anonymous troll accounts to meme on Lucifer’s posts but that’s neither here nor there-)

Therefore, naturally, you two go viral off of Asmo’s Devilgram.

Okay so someone in the obey me tag the other say headcanoned that Belphie will go out of his way to nap in ridiculous places and my brain really took that and RAN WITH IT.

So what happens is that Belphie will fall asleep in the fucking weirdest places. I’m talking on top of the fridge, underneath the dinner table, on top of bookshelves...you name it, he has slept there, no matter the effort it takes to get there in the first place.

And, ever since you two started dating, you would join him. Sometimes it involved putting yourself at risk of great bodily harm, but the little smile he gave when you he saw you fucking scaling the countertop to reach him made it worth it.

So anyway, since Beel adores the both of you to no end, he takes pictures whenever he sees you two napping together, whether or not it is in a crazy place. He sends these to the family group chat because he thinks they’re adorable.

Over a span of weeks to months, Asmo has built up a stock of images of you and Belphie cuddles up in seemingly impossible places. Once he has about ten or so, he posts a compilation of them to his Devilgram with some cheesy ass caption like “The things we do for love <3″.

They become a meme SO QUICKLY. Like UNBELIEVABLY quickly.

The picture of you and Belphie sleeping on top of a bookshelf, in particular, is a big hit. Memes abound.

“If my girl doesn’t climb up a bookshelf to cuddle my ass, she don’t love me.” “Get yourself a partner who scales bookshelves just to be with your ass.” Etc etc...Belphie doesn’t give a shit but you laugh at a lot of them so he sees that as a good outcome.

#IM SO HAPPY TO HAVE FINALLY WRITTEN THIS#obey me#my writing#obey me headcanons#obey me x reader#lucifer#mammon#leviathan#satan#asmodeus#beelzebub#belphegor#posts

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Ranking the Bridgerton Books

I know I should write this in my book blog, but frankly, I have no idea how to make another section for it, and I'm too lazy to research. So, I'm writing here. Please bear with me.

Recently, I read the Bridgerton books by Julia Quinn. You might be familiar with the first book since it was adapted into a popular Netflix series by Shonda Rhimes. I binge-watched it back in December, and I have to say... not a fan. I guess I just find it too cheesy and annoying. Plus, the actors who portrayed Daphne and Simon had no romantic chemistry whatsoever.

But I'm not here to talk about the TV show. I'm here to talk about the novels! This is actually not my first time reading the books. Well, not exactly. I've read six out of the eight novels when I was in high school, I believe. I found the books when I was in high school as it was in the library (please don't ask me why my high school library has smutty novels in it, I have no idea who's in charge - they had Fifty Shades of Grey for a week but they eventually removed it from the catalog when they learned what's it about, but I digress). As a fifteen-year-old girl, the series hooked me.

If you're not familiar with the books or the Netflix series, here's a short synopsis: Set in the Regency era, the Bridgertons are one of the most influential families of the ton. The books follow the love stories of the eight Bridgerton siblings, alphabetically named Anthony, Benedict, Colin, Daphne, Eloise, Francesca, Gregory, and Hyacinth.

I didn't read it in chronological order back then, though. I just borrowed any available Bridgerton book in the library if there's one. You might think I was too young to read a romantic novel like that, but I guess I was mature enough to understand it.

Rereading it now that I'm twenty-two (cue Taylor Swift!), my heart's not in the same place. I was more skeptical with the writing, the story, and, most especially, the characters. But, really, I'm not that heartless, so I will cut the author some slack. Quinn wrote this at a different time for a different audience. It's not that long ago, but you'd be surprised how fast things change.

However, even though I have major criticisms, I cannot stop reading them. There's something about the novels that put me in a chokehold. Despite everything, I was able to enjoy it overall. This series is the definition of "guilty pleasure."

Anyway, here's my ranking of the Bridgerton books! I only read the eight main ones, which means I didn't include novellas of any kind. Also, as a fair warning, I might discuss spoilers and whatnot, so please beware. And do keep in mind that I'm writing my opinion, so if you don't agree, well... tough. I'd like to hear your comments, though, if you have any.

#8 - An Offer From A Gentleman (Book 3)

Honestly, this was probably one of my favorite Bridgerton books when I was younger. A Cinderella retelling? Come on! As someone who loves fairytales and forbidden romances, this was supposed to be heaven. However... it was not.

Benedict may be my least favorite Bridgerton brother. No, scratch that - he is my least favorite Bridgerton out of all of them. He's whiny and creepy and I was plainly annoyed with how he keeps asking Sophie to be his mistress in the novel. This was not the gentleman I imagined when I was younger. I might have liked him more in the first few parts, but as the story progressed, he became too childish and obsessive. Sophie, on the other hand, was all right. She's definitely one of my favorite Bridgerton heroines. She was tough but kind in her own way. I wish she had a better partner than Benedict, but I guess they suit each other in the end.

I just detest the climax and the ending of this book. It was too comical - and not in a hilarious way. I guess the same could be said for the entire novel. This was so, so different from the rest, to be honest.

Overall Rating: 3/10

#7 - On The Way To The Wedding (Book 8)

Fun fact: this is the first Bridgerton novel I read. And even then, I wasn't a huge fan of it. Just like An Offer From A Gentleman, the climax was a bit silly but more in a soap opera level than comical.

The biggest factor why I didn't like this was the characters. They were all so bland. Especially our hero and heroine. Gregory is the least featured Bridgerton in the novel, so I don't really know what to make of him at the beginning of the novel. In his book, I learned that he was a good guy - and that's all. Maybe he's too young and naive when it comes to romance (which is endearing, I have to admit), but he has no interesting personality whatsoever. Lucy, the heroine in this novel, was the same. She was described as pragmatic and sensible, which perfectly sums her up. Also, she's a great friend to Hermione (whose last name is Watson, by the way, and you can't tell me otherwise that this isn't a Harry Potter reference - Hermione Granger and Emma Watson? If that's not a reference, well, that's a very crazy coincidence, but I digress again). Gregory and Lucy's story was average - not bad, not good, just so incredibly dull.

The fun parts started way too early. It was difficult to find intrigue in the middle and end bits. The second main conflict, which happened near the end of the book, was truthfully not that good and was just obviously a ploy to keep things longer. You'd think that the Bridgerton novels would end the series with a bang. Alas, it did not.

Overall Rating: 4/10

#6 - To Sir Phillip, With Love (Book 5)

Eloise finally gets her turn in her own love story. She used to be one of my favorite Bridgertons, but when she got her own story, she was reduced into a plain girl. Gone was the feisty and outspoken Eloise we knew from the previous books.

Maybe it's because she's paired up with one of the most insufferable Bridgerton heroes, Sir Phillip. Just an inch away from Benedict, Sir Phillip maybe my next least favorite character. And it annoys me so much that Eloise gets to fall in love with someone like him.

It actually started pretty well. Before the events in the book started, Eloise and Phillip had already been corresponding for a year through letters. Phillip was on the lookout for - not a wife - but a mother for his two unruly children, and he thought Eloise was perfect for the role. He's a terrible father, but the book tries to convince us that it's not his fault because he had a bad upbringing by his own father (a recurring theme in the Bridgerton books - four heroes are plagued with different daddy issues). Eloise tried her best to turn things around, and of course, she eventually did, but I just really hate Phillip's initial intentions for seeking out a wife. He gets better in the end, sure, but I still really don't like him. At least the book wasn't short of excitement, else it would've been rated a bit lower.

Obviously, my favorite part in this book was when the Bridgerton brothers stormed into Phillip's house. He got what he deserved, truly.

Overall Rating: 4/10

#5 - The Duke and I (Book 1)

Now, this is the most well-known story in the Bridgerton literary universe, thanks to the Netflix series. I know I've said that I wasn't a fan of the series, but really, the Netflix writers and producers deserve all the gold in the world because they managed to transform this novel into something exciting.

Daphne and Simon had their moments, that's for sure, but as a couple, they were just so... meh. I liked their relationship at the start when they were still pretending to be courting. But as soon as they got married, everything interesting about the two of them sizzled out. And please don't get me started with how Daphne "took advantage" of drunk Simon. Thank God the show fixed that.

Despite my mixed feelings, this was a decent start to the Bridgerton books. There's really nothing majorly wrong about this novel (except for the aforementioned "taking advantage.") It laid out the future characters well. Lady Whistledown was also great. Thinking about her made me miss her because she wasn't featured in the later novels (you'll soon find out why).

Overall Rating: 5/10

#4 - It's In His Kiss (Book 7)

Since Eloise was stripped away from her feistiness when she got her own love story, I was obviously worried for Hyacinth. Thankfully, she didn't change! She was still the same tactless girl in the previous books. And for that, she gets to be my champion as my favorite Bridgerton.

This is the first time I've read this book, and oh, I'm surprised with how exciting it was. Hyacinth's hero, Gareth, perfectly suited her. Gareth was able to tame her impulsiveness, while also proving to be a good romantic partner for her. I loved that he could match her intellectually, too. It was never a bore whenever they have one of their silly banters. Lady Danbury was also featured more in this novel. She's one of my favorite side characters. As Gareth's grandmother, she was determined to bring him and Hyacinth together.

Maybe the only criticism I have in this novel is Gareth's issues with his father. I find it really weird that most of the heroes' problems are with their fathers. It just seemed lazy writing, in my opinion. But oh well, Gareth was interesting in his own way and that's perfectly fine.

Overall Rating: 6/10

#3 - Romancing Mister Bridgerton (Book 4)

I have a feeling that this is Quinn's favorite Bridgerton book. In this book, it's Colin's turn to find love. Colin is featured in several of his siblings' stories - in fact, in almost all of the books, he had an important role to play.

I love Colin and Penelope's story. Long before this book, they already knew each other. Penelope was Eloise's best friend, and she's almost always in the Bridgerton household. Colin has been forced by his mother for God knows how long to dance with Penelope every time there's a party. But it was only now that they became closer. Unbeknownst to Colin, Penelope had been in love with him for half her life, even though he didn't particularly care for her. Penelope speaks for all of us who know about unrequited love all too well.

Furthermore, this is the novel where they finally reveal who was behind the Lady Whistledown column. Yes, viewers of the Netflix series who are not familiar with the books. This is the part - and not in the first book! I'm so mad that they revealed Penelope as Lady Whistledown in the first season of the series, when in fact it's much later than that.

However, that's also one of the lowest points of this novel for me. Lady Whistledown's identity reveal was a bit anti-climactic. A little bit laughable, even. Also, also, also: I hated Colin's reaction to Penelope's secret. He didn't have to be angry and jealous of her, but ah well, whatever makes for conflict. Nevertheless, I love both Colin and Penelope because they had so much character and depth. Quinn was certainly biased when she wrote this.

Overall Rating: 8/10

#2 - The Viscount Who Loved Me (Book 2)

Remember earlier when I said that I cannot stop reading the books because even though I knew it wasn't that good, it was still highly enjoyable? Well, I'm really talking more about this book, to be specific. I think I've read it in less than 24 hours because of how much I love it. And yes, Anthony and Kate had their obvious flaws, but oh God, they were so perfect together. I can't help but imagine Jonathan Bailey from the Netflix series as Anthony when I was reading it. I swoon, all the time.

This used to be my favorite Bridgerton novel, but that's only because I haven't read my new favorite until recently. Anthony and Kate's story was just oh-so good and intimate and romantic. Kate's also my favorite heroine in the entire Bridgerton literary universe. She was headstrong and loving. She's unafraid to put the happiness of her family first.

In so many ways, Anthony was the same. He assumed the role of Viscount Bridgerton when he was only eighteen when his father unexpectedly died. Since then, he overlooks the family's estates and well-being. Yes, this is one of those "daddy issues" stories I mentioned earlier, but this one was kind of done tastefully. He didn't wish to fall in love but everything changed when he encountered Kate. He didn't mean to be attracted to her, but here we are.

Anthony and Kate had so much understanding between them. I agree Anthony was a bit of a dick when Kate asked if they could have one week to get to know each other before consummating the marriage (worse things have been said by Benedict and Phillip, though), but in the end, I can't deny that I truly love them together.

Overall Rating: 8/10

#1 - When He Was Wicked (Book 6)

*blushing furiously* So what if I put the smuttiest and steamiest novel as my top choice?! What about it? Oh, but really, though, I can't stop reading this. Francesca is one of the least known Bridgertons in the books, just like Gregory. I didn't know anything about her, except that she's quieter than most of her siblings. It was also first mentioned in Romancing Mister Bridgerton that she had already married but was sadly widowed after two years.

Michael was Francesca's late husband's cousin and best friend, which makes him her best friend, too. He has been secretly in love with Francesca since the first moment he laid eyes on her but was unable to pursue her because she's with his cousin John. In addition, I'd like to say that Michael is my favorite hero in the Bridgerton books. He's very charming and wicked, and really, my knees buckle at the thought of him.

Long after John passed away, Francesca and Michael reunited. Francesca was looking for a new husband because she desperately wants a family, while Michael... well, Michael was still in love with her. There was undeniable passion and intimacy between them, and it was hard to stay away from each other. I seriously have a thing for men secretly pining over women they love. That's got to be one of my favorite tropes.

However, the book itself was a bit longer than necessary. While I understand Francesca's hesitations in marrying Michael, it could've been shortened because it felt draggy by the end. Her constant changing of minds was a bit annoying, and yeah, it was probably a ploy to lengthen the novel.

Additionally, I was a bit skeptical at first of how they're going to treat their relationship, especially since Francesca was truly in love with her first husband. But it was done so nicely. Francesca and Michael never forget about John, even in the end. I loved what John's mother said to Michael in a letter at the end, "Thank you, Michael, for letting my son love her first."

I guess I love their story more than the other couples because both were already mature and experienced. Just like everyone else in this romantic series, Francesca and Michael belonged together. The entirety of Chapter 19 is proof of that.

Overall Rating: 9/10

***

Overall, the Bridgerton books are quite entertaining, despite being a cheesy and sappy series. I admit that I feel quite lonely and bored now that I've finished all eight of them. Ah well, there's always the possibility of rereading them!

#books#bridgerton#bridgerton books#julia quinn#novels#reading#book ranking#romance#romantic books#historical fiction

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jo’s Boys: Chapter 2 Parnassus (Part 2) May and Amy

As I said on Part 1 of these chapter post, the following quote says so much about Amy, but also relates to May.

...for she was one of those who prove that women can be faithful wives and mothers without sacrificing the special gift bestowed upon them for their own development and the good of others.

May married before Louisa started writing this book. It looks like Louisa was very interested in how May balanced family and work. At the time women had two options, either they focused on their careers or they get married. Trying to combine them seemed crazy.

There were a few literary works addressing this issue at the time. In 1877 Elizabeth Stuart published The Story of Avis which depicted a woman who gave up her art after getting married. Louisa read this book and warned May about it, but her sister was determined to prove those thoughts wrong. She writes,

‘I mean to combine painting and family, and show that it is a possibility if left alone.’

This blessed lot is mine, and from my purpose I shall never be diverted... I am free to follow my profession, I have a strong arm to protect, a tender love to cherish me and I have no fears for the future.

And indeed she succeeded those two years of marriage. In fact, 1879 proved to be one of May’s most prolific and successful years of her career. It’s such a shame May died just weeks after giving birth when her career was going so well.

To quote that same letter, “May decided wisely”, and Amy too.

There’s the idea that Amy stopped pursuing an artistic career because Louisa was jealous of how easy things came for May. She wasn’t wrong. May was incredibly lucky and there was always someone willing to help her. And as the baby of the family, she was often shielded from the hardships of life. So if Louisa was bitter, I wouldn’t blame her (although she pampered May too). And if this were true, I think her vision of May changed by the time she wrote this book.

I think Louisa gave Amy this development as part of her curiosity and admiration towards her own sister. 🥰 🥰 🥰

Come to think if it, Amy never really stopped drawing. After rejecting Fred, Louisa tells us that Amy has a quieter trip and that she spends her time sketching ( faceless knights in shinny armor or couples dancing, but that’s another story 😉 ). And in the last chapter, Amy is making a bust of baby Bess. Of course Amy would never drop her art, even if she tried. It’s such a fundamental part of who she is that it’s impossible for her to stay away from it. It defines her and differentiates her from everyone else around her.

Now, long has been discussed about May’s approval or dislike towards the character of Amy. The only direct quote I have found from May about Amy is a letter to Alf Whitman where she refers to her book counterpart as “horrid stupid”. She might be referring to Amy’s selfishness and vanity, as she recognizes she was the same once but now she is changing (like Amy did). However, this was before Part 2 was published.

Regardless, I am convinced that May would have loved how Amy’s life turned out. May was an incredibly generous person who dreamed of offering art to everyone, no matter the social class nor the color of their skin. She was always willing to help a fellow artist. She gifted Daniel Chester French his first sculpting tools, yeah THE Daniel Chester who sculpted the Lincoln Memorial! (In fact, he wrote the preface for May’s Memorial by Caroline Ticknor in 1928. He was always grateful for all the support and encouragement May gave him.)

Another thing that Amy and May have in common is the criticism towards their marriages. Many people don’t consider May feminist enough because she didn’t participated in the suffragette movement, she got married and she expressed how much she loved her domestic life. Who cares if she openly criticized the art system and spoke openly about the unequal opportunities that women have in artistic education. Even less, if she rejected multiple suitors until she found the right one, someone who would love her and respect her career.

In one of her letter, she said,

‘the lonely artistic life that once satisfied me seems the most dreary in the world’

Many people judges her and claims that she succumbed to the patriarchy. Really, what May was calling “dreary” was the lonely life she had. She was in Europe away from the rest of her family, she couldn’t even say goodbye to Marmee when she died. She was depressed for a while and felt guilty for not coming back home. The only person who was able to cheer her up was Ernest (like Laurie did with Amy 😊 ). She could go wherever she wanted because she had nothing attaching her to a certain place. But May always dreamed of marriage and a family. In a previous letter she says,

If mine can’t be a happy domestic life, as such as I have longed for and prayed for, perhaps the good God meant me for great things in other ways.

Just months before meeting Ernest, she still dreamed of romance! So sue her if she was happy with her husband and her domestic life. That was her dream.

I haven’t finished reading The Story of Avis, but by the synopsis, it seems that part of the problem was Avis’ husband and his lack of support towards her artistic career. This is an issue that neither May nor Amy had.

Ernest was one in a million. He never represented an obstacle to her career, on the contrary, he was an enthusiast. In the end, May got her Laurie 🥰 🥰 🥰

Now that I think of, Louisa followed the destiny of the real-life people in her characters. Beth, John and Marmee died in the novels because Lizzy, John and Marmee died in real life. However, she kept Amy alive.

Nobody expected May’s death. She had had such luck in life that it felt impossible for it to stop.

In various letters, May had asked Louisa to visit her in Meudon (where she lived with Ernest). Unfortunately, Louisa couldn’t go. There were responsibilities at home and her health was a big issue and she didn’t want to be a burden.

May’s death was devastating for Louisa. In one of her diary entries she remembers the last time she saw her, waving goodbye from the ship to London. Then she writes,

A lonely time with all away. My grief meets me when I come home, and the house is full of ghosts.

To me that phrase is incredibly personal. My grandparents and two of my aunts lived together. In the last years they’ve all been passing away and now the house that once was full of life is abandoned.

Louisa apologized in the preface of this book for writing little about Amy,

Since the original has died, it has been impossible for me to write of her,...

Indeed, I would have love to read more about Amy, but these first two pages about her are so important and tell us so much about her, her marriage and her career.

Maybe Louisa had already written this chapter before May’s death. Who knows. Maybe Louisa couldn’t bear another loss in her fictional family too. If May was gone, at least Amy would live and have a happy long life.

#there's a latter where Anna refers to May's 75th love affair#it migt be an exageration#but it does show how popular May was#little women#louisa may alcott#jo's boys#may alcott nieriker#amy march#amy laurence#ernest nieriker#may x ernest#amy x laurie

24 notes

·

View notes

Note

everyones entitled to their opinion but the amount of people who have been saying how “confusing” az’s chapter is and how sjm’s a bad writer for writing it that way honestly annoys me? you said you felt vindication when you read it and tbh, same, it confirmed everything i thought since acowar and made perfect sense with what we know of az as a character - that he’s deeply traumatized and incapable of creating and maintaining healthy relationships (as of rn). but beyond that, i dont see how it was unclear in the terms of which ships will be endgame?? before that chapter i was still uncertain and thought it could go either way (tho i was leaning to elucien bc of the already existing bond), and now im pretty certain its not gonna be elr*el in the long term. idk, i just feel like a part of fandom has built their own vision of the characters and future events that isn’t supported by text and now that theyre disappointed it isnt canon, they blame sjm for it? i really dont think it was a confusing chapter at all, i thought her intentions were perfectly clear with the types of tropes she used, i dont think its fair to say it was badly written just bc it didnt support their fanon ideas that was built more on headcanons than actual textual evidence... idk if i sound mean lol but just my 2 cents, obviously it doesnt go for everyone i feel like a certain part of fandom has a certain version of characters in their heads that they consider as canon bc they want to see them that way, but they aren’t really the same as the actual characters we’re presented in their story

Anon, I am going CRAZY over here.

I’ve been trying to figure out why I take on some arguments and others I don’t, and it basically comes down to 1) what is supported in the text, 2) people’s very wild interpretations of the text, and 3) people confusing their interpretation, fanon, what have you, with canon.

I actually make my students read this article before they respond to a text because it’s super important to understand what, exactly, they (and we) are responding to. It’s nothing to do with literary criticism, but it still has bearings here because people are taking lines of text and imposing these wildly different meanings that have zero support. Like I mentioned in this post, we cannot say why Elain’s face gets tight or she shrinks from Lucien. There is literally no evidence one way or another, so I could that she like....... has a bad problem with farting when he’s around and is embarrassed. And who’s to stop me????

And you’re right, the problem here is that they think they are responding to canon, when actually it’s this wild interpretation of canon that began before acowar even came out, for the sole purpose of furthering hate on Mor. It had nothing to do with actually, genuinely liking it. But it’s grown into this monstrosity we see today and yeah... people are literally making posts where their “evidence” is two people being a room together and noticing that fact = endgame super romantic ship.

And that’s totally different from actually acknowledging the bare minimum of evidence, and saying “fingers crossed I hope it happens because I love it!!” That would be fine. I literally do not care if people do that. I do care when they willfully misinterpret what’s on the page and try to act like 1) they have found facts, and 2) they pretend like that “fact” should have any bearing on what other people ship.

So, re: Az.

I literally made this argument four years ago lol and if you read it real quick you can see that that ship came about (in January 2017) not because of all this “evidence” people found in acowar, which didn’t exist yet for us, but before that for other fandom, fanon reasons.

And since acowar came out, I’ve pretty much avoided talking about Az because I know that somehow, the fact that he’s dark and twisty is.... controversial??? Yeah, I compared him to Tamlin and I still hold to that (I saw a vagueblog about my idea and I still think that comparison is accurate, but anyway). But people just? Don’t want to hear anything like that about Az. Even though that’s literally what we are given.

There is nothing wrong with saying that he’s dark af. In fact, all of the evidence we have from the book is that he is not only dark, but that he is increasingly losing control. There was the blowup in acowar, and the increased disrespect of Rhys (and Feyre) in acosf, refusal to take orders from someone he is supposedly so loyal to. Even back in acomaf there were multiple signs that Mor was concerned about bruising his ego (literally the first thing that Mor says about Az is that he would want to know something, I’m not going to look it up but the implication was that he would be upset if he didn’t know).

From acosf:

Az had a vicious competitive streak. It wasn’t boastful and arrogant, the way Cassian himself knew he himself was prone to be, or possessive and terrifying like Amren’s. No, it was quiet and cruel and utterly lethal. (pg. 254)

“He’d tortured it out of someone. Of many people.” (pg. 224)

“Some silent conversation passed between him and his mate, and Cassian knew Rhys was asking about the torture - apologizing for making Feyre witness even the ten minutes Azriel had worked. (pg. i lost my place idk)

“Opening movements in a symphony of pain that Azriel could conduct with brutal efficiency. (pg. 375)

So asdkhasldkjasda if only we could STOP saying that Az is actually a dark soft boi and just acknowledge that he’s fucked up and that him being with ANYONE at this point would potentially be harmful to that person, be it Elain or Gwyn or whoever? That chapter did NOTHING but continue a line of character development that had already been in place, and I get the need to romanticize dark boys, but idk, don’t pretend he’s something he’s not.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

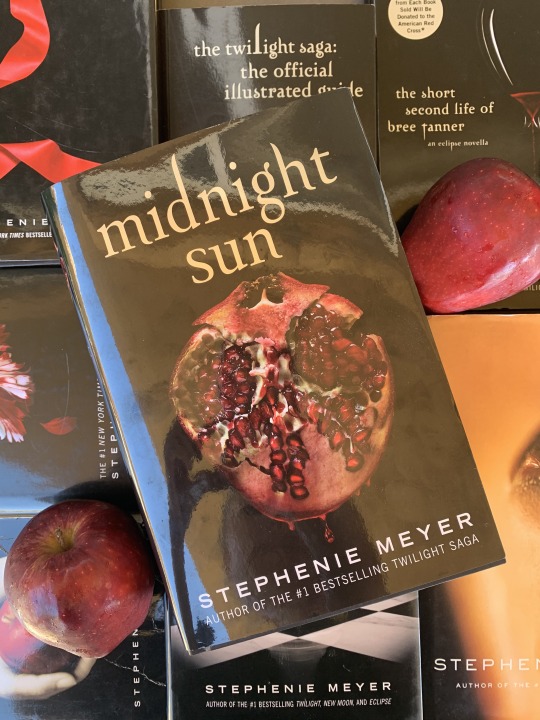

Midnight Sun Book Review

Midnight Sun Book Review by Stephenie Meyer

Oh my god, you guys.

Just. Oh. My. God.

This book took ten years off of my life.

As a heavy reminder, these book reviews are entirely subjective and my very personal opinion. I don’t need the hoards of Twihards coming after me with pitchforks and pretend fangs from Party City because I didn’t fall head-over-heels with this canon spinoff like my fourteen-year-old self would have.

With that measly disclaimer out of the way, let’s move onto the actual book review. If you haven’t heard of Midnight Sun or don’t know what it is, then I don’t know what to tell you except that you avoided 600 plus pages of stream of conscious ranting.

For those of you that would like to be enlightened, Midnight Sun is the retelling of the infamous Twilight book-yes, that Twilight, Robert Pattinson as Edward Cullen Twilight, complete with vampires, not so-stellar acting, and the more than notorious forest scene of Edward demanding she say… “vampire!” Gasp.

But no really, like most women in my now mid-20’s, as a teenager, I was obsessed with the Twilight saga and everything it had to offer, especially the dreamy, chivalrous, too good to be true Edward Cullen (fuck Jacob).

I voraciously devoured the books while I was in middle school, attended the midnight book premier for Breaking Dawn, and stayed up way too late for each and every movie screening that followed, a loyal fan to the end. To give you some perspective, I even joined the Twilight club my freshman year of high school.

Yes, if you were wondering, I was indeed that cool.

I was obsessed and in love and outside of Harry Potter, it’s still one of the few book fandoms and series that I was truly enveloped and consumed by. Whether that was due to my age, the experience of the fandom, the cultural phenomena that was following the movies and new releases, or for other reasons, it was an experience I look back on now with simultaneous fondness and slight embarrassment.

I wasn’t embarrassed by my involvement or my experience in the fandom, like many other people, I made great friends through Twilight (including my best friend, whom I met in college when we mutually bonded over our love of Twilight), read countless fanfiction that, to this day, I still remember and cherish with my heart, and it was one of the series that cemented my love of reading and book culture as a whole for me.

However, like everyone else, I inevitably grew up, matured, and my reading tastes changed and became more refined. As an avid re-reader of books, I have tried going back to re-read the Twilight saga multiple times...

...and failed.

The books had simply lost their magic for me.

The story seemed dull and nonsensical, Bella had become the epitome of a Mary Sue, the writing was now apparently mediocre, and Breaking Dawn’s lackluster climax angered me to the point of speechlessness (it still does).

So, I gave up re-reading the series and while I deemed that it was perhaps not as wonderful and life-changing as it had been for 8th grade Melissa, I still appreciated what it had done for me personally and the experiences that I had gained through the books.

Speaking of 8th grade Melissa, the original Midnight Sun, that being twelve chapters of the original manuscript that had been leaked back in 2008, had been put up on Stephenie Meyer’s website for all to enjoy.

Like the good, whipped fangirl I was, I devoured all 12 chapters with ease and lamented the loss of never getting more than that snapshot of Edward’s thoughts and musings.

Now, twelve years later, the full book has been written, published, and released to the delight and downright shock to many age-old Twilight fans that had believed that series to be dead and buried, myself included.

So, when the book came out this August, I swallowed my trepidation, knowing that my love for the characters was now long gone, but I believed that the sentimentality of 8th grade Melissa’s obsession would long linger, making this a pleasant blast from the past to lift my mood.

Unfortunately, this wasn’t the case.