#I will suffer if it means I get to read Sappho’s poetry in the language it was written in

Note

OC question (not really a question but whatever): pick a work written in classical Greek or Latin to recommend to each of your OCs! What would they enjoy reading or which works would include valuable information for them?

Ohhh this is a good one!! Thanks Vanamo!! You know me well so you’re not gonna be surprised when this is a long answer 😅

I think Herah would really love the poetry of Sappho. I know this is kind of an obvious choice but I think the personal nature of lyric poetry would suit her well. The sense of community and the performance context are things I think would remind her of her Tal Vashoth community. I’ll probably do a post on this at some point but, since it’s relevant here, I think that the Vashoth probably have an oral tradition given that that’s an important part of almost all communities ever. It’s a way for members of a community to connect to one another over common stories/experiences, a way to impose a moral code, and to define how we ought to treat each other and what happens when that goes wrong. Connecting with those ideas and exploring how another culture is similar/different to her own would be really rewarding for Herah.

Also hearing Sappho communicate directly with Aphrodite, reading her symptoms of love, listening her play into existing myth and look at it in new ways would be really appealing to Herah. The differences in language and metre would also give her the opportunity to get stuck in and do the kind of close analysis that she loves so much. She’d really be able to dig her teeth into it and see all the nuances of word order and emphasis, and admire how compact and economical these poems are.

I know this is cheating but I just wanna add that I think Herah would really love to read some Athenian comedy with Sera. They’d have so much fun with the Cyclops with all its sex jokes and taking the absolute piss out of Odysseus as this self-important war hero whose fame means nothing without a social framework in which to operate.

After much debate, I think I’d recommend to Naerselle the Iliad. She’d really like the close descriptions of battle (I almost said Julius Caesar’s Gallic Wars for that reason) but I think she’d really understand the sorrow of Achilles, his attempt to defy destiny, how his action (or inaction) hurt a lot of people, but in time he realises just how much that cost him on a personal level. Not only that though, I think she’d also relate to Hector at times, not because of his nobility (in the moral sense) but because of how alone he is at times even when he has such an extensive family. She and her own family are mostly at odds and I think she sees something of them in Paris making her by extension a Hector-like figure.

Given that she’s Andrastian (probably my OC with the strongest sense of faith), I think she’d enjoy how present the gods are in this text, even if they are perhaps portrayed as ambiguous at times. Her faith doesn’t necessarily mean that she thinks that the Maker has a strong sense of right and wrong which he imposes upon the world. She sees it more as he has an overarching plan (like Zeus’ Βουλή in the proem) which may indeed require suffering along the way.

I know Senna would love historiography so I think I’d recommend Sallust’s War on Catiline or Jugurthine War. Sallust’s style is moralising and very self-conscious as his discussion of events often reveals either explicitly or implicitly where he himself lies politically. It’s also pretty important to him to justify why he’s taking the time to write history when he maybe should be dedicating time to politics. The position of being stuck between personal pursuit and political duty is something Senna could relate to, being at the centre of politics for as long as she can remember. Sallust, in my opinion, has this surface view of binary morality, but also his deeper ambiguity on whether we are right to accept the official narrative (particularly in the Catiline). I think that’d feel familiar to Senna, especially after her exile from Orzammar.

I also think it’d be helpful for her from a rhetorical and political point of view as seeing the shades of grey and how people might do bad things for good reasons or vice versa would give her perspective on how she herself should or could view the world around her. The end of the Catiline is particularly striking because all of the remaining supporters of the Catilinarian conspiracy fight valiantly and to the death — notably within no wounds to the back (ie they didn’t flee from battle). Seeing a political opposition be so sure that what they’re doing is right might make her question her own actions and think about how she’ll be remembered in history.

For Nesiril, I’m stuck between either Euripides’ Medea or Aeschylus’ Agamemnon. I think they’d like to see how gender roles can be pushed and even totally disregarded at times and she’d definitely take the reading of extreme support of the women in these plays in the face of the abominable actions of the men around them. Moreover, I think they’d see Jason and Agamemnon as parallels for the Templars in the Circle — controlling, power-hungry, and neglecting their duties or outright contradicting them.

I think she’d also see herself in Medea in particular from a gender point of view because there’s this scene in which Medea renounces her femininity and basically steps outside of the gender binary. Given that Nesiril is non-binary, I think she’d find this a really powerful moment and really gender affirming.

#answered asks#thanks for the ask!#dragon age#oc: herah adaar#oc: naerselle cadash#oc: senna aeducan#oc: nesiril surana#hannah talks classics

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Me: why am I taking this language I am in hell I never want to translate again

Also me: plans to take this language for the rest of college

#I will suffer if it means I get to read Sappho’s poetry in the language it was written in#and also a whole bunch of Homeric shit but that’s all for later#also it really is fun when I’m translating stuff from like… people I actually know#I also will translate any myth with no complaints#signed#your local chaos being#Classical Greek#gotta learn Homeric Greek after that

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anonymous asked: As a beginner in Classics I love your Classicist themed posts. I find your caption perfect posts a lot to think upon. I suppose it’s been more than a few years since you read Classics at Cambridge but my question is do you still bother to read any Classic texts and if so what are you currently reading?

I don’t know whether to be flattered or get depressed by your (sincere) remarks. Thank you so much for reminding me how old I must come across as my youngish Millennial bones are already starting to creak from all my sins of past sport injuries and physical exertions. I’m reminded of what J.R.R Tolkien wrote, “I feel thin, sort of stretched, like butter scraped over too much bread.” I know the feeling (sigh).

But pay heed, dear follower, to what Menander said of old age, Τίμα το γήρας, ου γαρ έρχεται μόνον (respect old age, for it does not come alone). Presumably he means we all carry baggage. One hopes that will be wisdom which is often in the form of experience, suffering, and regret. So I’m not ready to trade in my high heels and hiking boots for a walking stick and granny glasses just yet.

To answer your question, yes, I still to read Classical literature and poetry in their original text alongside trustworthy translations. Every day in fact.

I learned Latin when I was around 8 or 9 years old and Greek came later - my father and grandfather are Classicists - and so it would be hard to shake it off even if I tried.

So why ‘bother’ to read Classics? There are several reasons. First, the Classics are the Swiss Army knife to unpick my understanding other European languages that I grew up with learning. Second, it increases my cultural literacy out of which you can form informed aesthetic judgements about any art form from art, music, and literature. Third, Classical history is our shared history which is so important to fathom one’s roots and traditions. Fourth, spending time with the Classics - poetry, myth, literature, history - inspires moral insight and virtue. Fifth, grappling with classical literature informs the mind by developing intellectual discipline, reason, and logic.

And finally, and perhaps one I find especially important, is that engaging with Classical literature, poetry, or history, is incredibly humbling; for the classical world first codified the great virtues of prudence, temperance, justice, loyalty, sacrifice, and courage. These are qualities that we all painfully fall short of in our every day lives and yet we still aspire to such heights.

I’m quite eclectic in my reading. I don’t really have a method other than what my mood happens to be. I have my trusty battered note book and pen and I sit my arse down to translate passages wherever I can carve out a place to think. It’s my answer to staving off premature dementia when I really get old because quite frankly I’m useless at Soduku. We spend so much time staring at screens and passively texting that we don’t allow ourselves to slow down and think that physically writing gives you that luxury of slow motion time and space. In writing things out you are taking the time to reflect on thoughts behind the written word.

I do make a point of reading Homer’s The Odyssey every year because it’s just one of my favourite stories of all time. Herodotus and Thucydides were authors I used to read almost every day when I was in the military and especially when I went out to war in Afghanistan. Not so much these days. Of the Greek poets, I still read Euripides for weighty stuff and Aristophanes for toilet humour. Aeschylus, Archilochus and Alcman, Sappho, Hesiod, and Mimnermus, Anacreon, Simonides, and others I read sporadically.

I read more Latin than Greek if I am honest. From Seneca, Caesar, Cicero, Sallust, Tacitus, Livy, Apuleius, Virgil, Ovid, the younger Pliny to Augustine (yes, that Saint Augustine of Hippo). Again, there is no method. I pull out a copy from my book shelves and put it in my tote bag when I know I’m going on a plane trip for work reasons.

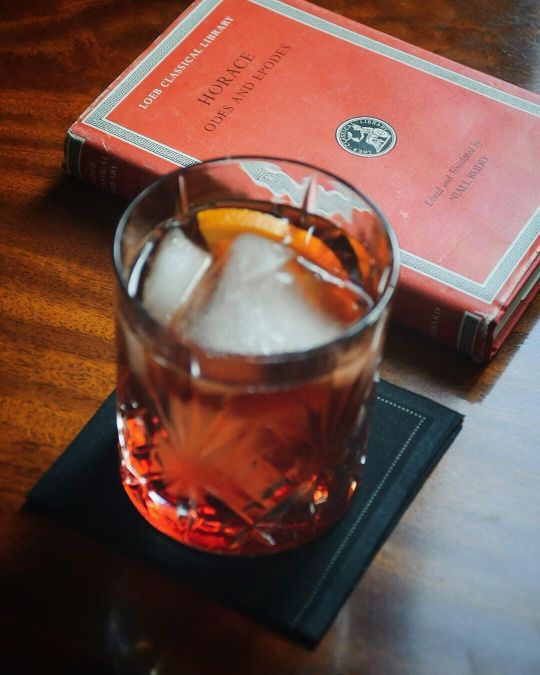

At the moment I am spending time with Horace. More precisely, his famous odes.

Of all the Greek and Latin poets, I feel spiritually comfortable with Horace. He praises a simple life of moderation in a much gentler tone than other Roman writers. Although Horace’s odes were written in imitation of Greek writers like Sappho, I like his take on friendship, love, alcohol, Roman politics and poetry itself. With the arguable exception of Virgil, there is no more celebrated Roman poet than Horace. His Odes set a fashion among English speakers that come to bear on poets to this day. His Ars Poetica, a rumination on the art of poetry in the form of a letter, is one of the seminal works of literary criticism. Ben Jonson, Pope, Auden, and Frost are but a few of the major poets of the English language who owe a debt to the Roman.

We owe to Horace the phrases, “carpe diem” or “seize the day” and the “golden mean” for his beloved moderation. Victorian poet Alfred Lord Tennyson, of Ancient Mariner fame, praised the odes in verse and Wilfred Owen’s great World War I poem, Dulce et Decorum est, is a response to Horace’s oft-quoted belief that it is “sweet and fitting” to die for one’s country.

Unlike many poets, Horace lived a full life. And not always a happy one. Horace was born in Venusia, a small town in southern Italy, to a formerly enslaved mother. He was fortunate to have been the recipient of intense parental direction. His father spent a comparable fortune on his education, sending him to Rome to study. He later studied in Athens amidst the Stoics and Epicurean philosophers, immersing himself in Greek poetry. While led a life of scholarly idyll in Athens, a revolution came to Rome. Julius Caesar was murdered, and Horace fatefully lined up behind Brutus in the conflicts that would ensue. His learning enabled him to become a commander during the Battle of Philippi, but Horace saw his forces routed by those of Octavian and Mark Antony, another stop on the former’s road to becoming Emperor Augustus.

When he returned to Italy, Horace found that his family’s estate had been expropriated by Rome, and Horace was, according to his writings, left destitute. In 39 B.C., after Augustus granted amnesty, Horace became a secretary in the Roman treasury by buying the position of questor's scribe. In 38, Horace met and became the client of the artists' patron Maecenas, a close lieutenant to Augustus, who provided Horace with a villa in the Sabine Hills. From there he began to write his satires. Horace became the major lyric Latin poet of the era of the Augustus age. He is famed for his Odes as well as his caustic satires, and his book on writing, the Ars Poetica. His life and career were owed to Augustus, who was close to his patron, Maecenas. From this lofty, if tenuous, position, Horace became the voice of the new Roman Empire. When Horace died at age 59, he left his estate to Augustus and was buried near the tomb of his patron Maecenas.

Horace’s simple diction and exquisite arrangement give the odes an inevitable quality; the expression makes familiar thoughts new. While the language of the odes may be simple, their structure is complex. The odes can be seen as rhetorical arguments with a kind of logic that leads the reader to sometimes unexpected places. His odes speak of a love of the countryside that dedicates a farmer to his ancestral lands; exposes the ambition that drives one man to Olympic glory, another to political acclaim, and a third to wealth; the greed that compels the merchant to brave dangerous seas again and again rather than live modestly but safely; and even the tensions between the sexes that are at the root of the odes about relationships with women.

What I like then about Horace is his sense of moderation and he shows the gap between what we think we want and what we actually need. Horace has a preference for the small and simple over the grandiose. He’s all for independence and self-reliance.

If there is one thing I would nit pick Horace upon is his flippancy to the value of the religious and spiritual. The gods are often on his lips, but, in defiance of much contemporary feeling, he absolutely denied an afterlife - which as a Christian I would disagree with. So inevitably “gather ye rosebuds while ye may” is an ever recurrent theme, though Horace insists on a Golden Mean of moderation - deploring excess and always refusing, deprecating, dissuading.

All in all he champions the quiet life, a prayer I think many men and women pray to the gods to grant them when they are caught in the open Aegean, and a dark cloud has blotted out the moon, and the sailors no longer have the bright stars to guide them. A quiet life is the prayer of Thrace when madness leads to war. A quiet life is the prayer of the Medes when fighting with painted quivers: a commodity, Grosphus, that cannot be bought by jewels or purple or gold? For no riches, no consul’s lictor, can move on the disorders of an unhappy mind and the anxieties that flutter around coffered ceilings.

Caelum non animum mutant qui trans mare currunt (they change their sky, not their soul, who rush across the sea.)

Part of Horace’s persona - lack of political ambition, satisfaction with his life, gratitude for his land, and pride in his craft and the recognition it wins him - is an expression of an intricate web of awareness of place. Reading Horace will centre you and get you to focus on what is most important in life. In Horace’s discussion of what people in his society value, and where they place their energy and time, we can find something familiar. Horace brings his reader to the question - what do we value?

Much like many of our own societies, Rome was bustling with trade and commerce, ambition, and an area of vast, diverse civilisation. People there faced similar decisions as we do today, in what we pursue and why. As many of us debate our place and purpose in our world, our poet reassures us all. We have been coursing through Mondays for thousands of years. Horace beckons us: take a brief moment from the day’s busy hours. Stretch a little, close your eyes while facing the warm sun, and hear the birds and the quiet stream. The mind that is happy for the present should refuse to worry about what is further ahead; it should dilute bitter things with a mild smile.

I would encourage anyone to read these treasures in translations. For you though, as a budding Classicist, read the texts in Latin and Greek if you can. Wrestle with the word. The struggle is its own reward. Whether one reads from the original or from a worthy translation, the moral virtue (one hopes) is wisdom and enlightenment.

Pulvis et umbra sumus

(We are but dust and shadow.)

Thanks for your question.

#question#ask#classical#greek#latin#horace#poetry#literature#arts#cambridge#classics#personal#study#habits#reading#books#culture#personal growth

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

“You ask, Aristippus, and I tell you / it’s in the waiting; that the moment, like a stag / may arrive at your doorstep as if from a cloud / and disappear before you know it, / not even the after-trace of a phantasm; / and you will have missed it for all your scheming, / your daydreaming about lofty verses and fame, / your lunging and casting about like a spaniel / barking his way into the middle of a slough, / then unable to get out.” Kleinzahler, from “Epistle XIV”, 2003

A couple of days worth of scribbles from one Google Doc. Much recent work is for publication elsewhere. The blog may be relatively quiet. Apologies. Enjoy my head turned inside out and gently browned.

03192017

In astronomy, the Pleiades, or Seven Sisters (Messier 45 or M45), is an open star cluster containing middle-aged, hot B-type stars located in the constellation of Taurus.

moving-words in sappho:

watched, go down, …

In linguistics, a compound verb or complex predicate is a multi-word compound that functions as a single verb. One component of the compound is a light verb or vector, which carries any inflections, indicating tense, mood, or aspect, but provides only fine shades of meaning. The other, “primary”, component is a verb or noun which carries most of the semantics of the compound, and determines its arguments. It is usually in either base or [in Verb + Verb compounds] conjunctive participial form.

In modern grammar, a particle is a function word that must be associated with another word or phrase to impart meaning, i.e., does not have its own lexical definition. On this definition, particles are a separate part of speech and are distinct from other classes of function words, such as articles, prepositions, conjunctions and adverbs. Languages vary widely in how much they use particles, some using them extensively and others more commonly using alternative devices such as prefixes/suffixes, inflection, auxiliary verbs and word order. Particles are typically words that encode grammatical categories (such as negation, mood, tense, or case), clitics, or fillers or (oral) discourse markers such as well, um, etc. Particles are never inflected.

there are about 200 irregular verbs;

The copula verb be has a larger number of different inflected forms, and is highly irregular.

[Pleiades] was later mythologised as the name of seven divine sisters, whose name was imagined to derive from that of their mother Pleione, effectively meaning “daughters of Pleione”. In reality, the name of the star cluster almost certainly came first, and Pleione was invented to explain it.

… goes, am

In about 300 BC, a doctor was summoned to diagnose the illness afflicting Antiochus, crown prince of the Seleucid empire in Syria. The young man’s symptoms included a faltering voice, burning sensations, a racing pulse, fainting, and pallor. In his biography of Antiochus’ father, Seleucus I, Plutarch reports that the symptoms manifested themselves only when Antiochus’ young stepmother Stratonice was in the room. The doctor was therefore able to diagnose the youth’s malady as an infatuation with her. The cause of the illness was clearly erotic, because the symptoms were “as described by Sappho.” The solution was simple: Antiochus’ father divorced Stratonice and let his son marry her instead.

…

Sappho has probably had more words written about her in proportion to her own surviving output than any other writer.

03202017

“If the repression is not completely effective, then a state of anxiety can be stimulated by the unconscious mind producing threatening feelings without the patient being aware of the reason for the anxiety. This is where the descriptions of the demons may help the incantation treat the sufferer. The process of denial can be influenced by focusing on the demons as the cause of the anxiety, particularly if it remind the patient of those intimate feelings which were originally repressed. Repression, as explained by Freud, takes many forms, some of which can clearly be detected in Mesopotamian incantations.” Freud, Magic and Mesopotamia: How the Magic Works

03212017

jacobus: “Just as literal or symbolic acts of erasure challenge the authority of iconic images, Dadaist techniques of collage overturn received narratives and subvert aesthetic hierarchies.” 19

03222017

“more equal” montfort 85

03232017

“I maintain my Twitter and Facebook for professional purposes.”

“I’m not allergic to mold.”

03252017

Rukeyser:

When I wrote of the women in their dances and

wildness, it was a mask,

on their mountain, gold-hunting, singing, in orgy,

it was a mask; when I wrote of the god,

fragmented, exiled from himself, his life, the love gone

down with song,

it was myself, split open, unable to speak, in exile from

myself.

There is no mountain, there is no god, there is memory

of my torn life, myself split open in sleep, the rescued

child

beside me among the doctors, and a word

of rescue from the great eyes.

No more masks! No more mythologies!

Now, for the first time, the god lifts his hand,

the fragments join in me with their own music.

”Emily Dickinson’s strictness, sometimes almost a slang of strictness, speaks with an intellectually active, stimulated quick music.” Rukeyser

“leveling of man” masons, heard in doc on burns

My favorite Queen song is, BY FAR, Princes of the Universe. What does that say about me?

03282017

Salcedo examines world violence and talks about the experiences of the victims. Refuses to let them be forgotten. Elevates them. The goal here is what? … So that we don’t forget? So that we can empathize… and change? So that in the split second before the sword meets flesh the executioner can pull up, pull out, disengage?

03292017

Reading Ruefle’s On Sentimentality: The internet as “Great Puddle of Sentimentality”. No time to expand on that right now, but good idea for an essay. Use her bibliography as a starting point. (John Gardner: “causeless emotion.”)

Bestowing upon one the permission to “see better”/”perceive better”/”sense better”/feel better” is the greatest gift a poet can convey. This is said in some form by Mary Ruefle in several sources. (Muck, a YouTube video from the Library of Congress where she speaks with Ron Charles, probably elsewhere…)

040220171022

“singing of black despair is some consolation for having to endure it.” Badiou, Black, 5

040520172010

I have a weird relationship with brilliant and eccentric people. I think a lot about how brilliance and that powerful cult-of-personality persona exhibited by a lot of religious/cult leaders a/o self-help gurus, celebrities, political figures, etc etc, are connected. I’ve been close to a few really brilliant people who can’t get along with others. is it a choice? a gift? a curse?

041020170713

“Poetry is never encoded–it is never a convert operation whose information is ciphered and must be deciphered–and yet it does incline toward self-concealment, insofar as it concentrates intently on what words conceal, or, to put it another way, on what language seeks to reveal. // It concentrates on the inside in an attempt to reverse the situation; to turn it inside out. // Every word carries a secret inside itself; it’s called etymology. // It is the DNA of a word.” Mary Ruefle, p91

Recent Notes A couple of days worth of scribbles from one Google Doc. Much recent work is for publication elsewhere.

#Alain Badiou#August Kleinzahler#Cy Twombly#Doris Salcedo#Mary Jacobus#Mary Ruefle#Muriel Rukeyser#Nick Montfort#Pleiades#Robert Burns#sappho#Sigmund Freud

0 notes