#Irish abortion

Text

I had a dream that I was watching The Terror again and it was… a bit different.

There was a plot where Francis Crozier was pregnant. Not by Fitzjames, no; they weren’t close like that. I think by someone who was 1) a casual hookup and 2) dead. He was confiding in Fitzjames about it, though, and complaining of breast soreness. Fitzjames asked him if he was sure he was pregnant and he said yes, that he recognized the symptoms from when he was younger, and then told a story about how his mother had helped him get an abortion when he was a teenager so he could pursue his then-incipient naval career.

Unfortunately, in the dream, I was watching this version of The Terror with my father and brother and they were confused. “But he’s a man! How is such a thing possible?”

“Transgender,” I explained impatiently, because it was obvious this was the direction the show had gone with the character, even though the actor playing him was still cisgender actor Jared Harris.

“But still, no way this would happen,” I added. “I mean, look at him. He’s GOT to be post-menopausal.”

#mt#this was like#well after the men had started dying#there’d been some disaster and the party had split and regathered#they’d gotten back onto the boat?#the ice had melted enough to sail a little?#mr hickey was there and kept trying to joint the conversation and Crozier kept telling him exasperatedly to drive the boat#all the while Crozier had a hand up his own shirt trying to relieve his#breast pain#anyway before you ask he DID have pale pink white person nipples. I seen them.#I think in the dream it was mastitis but that’s so rare antepartum#just one of the many ways the writing was unrealistic smdh!#but shout out to the imaginary Irish Catholic woman helping her kid get an abortion in like 1812. I DO want to believe. queen shit fr!#the terror#god Fitjames was such an idiot about it#it was like month four or five and he was like ‘do you think it could be a tumor’#TUMORS DONT KICK HE JUST TOLD YOU IT WAS KICKING#DUMB ASS#but he was genuinely concerned as a friend so some crimes can be forgiven#francis crozier’s geriatric pregnancy hour#edit: the croziers were from ulster and Presbyterian. my bad!#sorry for calling his ma a Catholic do you forgive me

325 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've been waiting to vote this fucking thing out of the constitution since I learned of it's existence in history class, it better go ahead. I, for one, would love to debate anyone who thinks this shite belongs in the 21st century

#i missed out on voting in the marriage equality blasphemy and abortion referendums#I've been legally able to vote for almost 3 years and there's been nothing#ireland#irish politics#the work done by people caring for family members should 100% be recognised and protected in the constitution#but the language should be gender neutral

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's been forty years since Ann Lovett, aged 15, died after giving birth inside a religious grotto, underneath a statue of the Virgin Mary. May she and all other women and girls who have died as a result of misogyny and patriarchy rest in peace. We can never underestimate the importance of women's liberation, and how it is an ongoing battle for women all over the world. Ann should still be alive today, but her life was snatched from her by a misogynistic society which treated women as lesser, held them to higher standards than men, allowed abuse to be flourish and stripped women of autonomy in more ways than one.

Suaimhneas síoraí dá hanam 🕊️

#feminism#pro choice#abortion rights#ireland#ann lovett#never forget#im NEVER gonna fw patriarchal religions#EVER. just learn about the amount of women whose lives have been ruined by them.#youre not convincing me that im inferior just for being born female#god isn't male#the irish state killed ann lovett. the catholic church killed her.#grma to foclóir.ie for the gaeilge. it translates as 'may she rest in peace'

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

I WAS LOOKING AT THIS PROFILE OF IRISH ARCHEOLOGY AND A THE RECCOMENDED POSTS HAD NAZIS IN THEM I ACTUALLY BLOCKED 2 NOW BUT IT WAS WAY WORSE BEFORE THERE WAS A BEER WITH "1488" AND STRAIGHT UP A BLACK SUN WITH A GUY TALKING ABOUT DRINKING MILK

WHAT THE HELL

#girl help#tumblr meta#irish history#ireland#archeology#tumblr#nazis#nazi#this account seems t=normal but wth is this the people who follow it or something#get out of tumblr dingus#I will eat your eyeballs cook your wife steal your milk abort your operations kill your crops poison your water and eat your vital organs

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

More rural pride stories:

The most ruthless and dedicated allies in a lot of rural Irish places are like. Gentle and kind middle aged women named after saints, herbs, and flowers. They're all very mom shaped and, having worked in social work for about 30 years, they are ready to fucking riot.

I rang a family resource centre to tell them about our pride events and I encountered such a creature. I told her that this was the first actual pride parade we'd ever had in the county and she was like. YES. I KNOW THIS. IT'S. ABOUT. TIME. I WILL TELL. EVERYONE. I will follow Majella to the baricades. Majella was a Valkyrie in another life i think.

#It's like#Have you ever seen moominmamma#They're moominmamas to a one#Irish shit#Queer tag#Me Fein#moominmama final Pam combo perhaps#If I was born into a country where women weren't allowed to have jobs once they got married. And divorce and queerness and abortion were il#Illegal#And then I worked within my own disadvantaged communities for 30 years. In that world. Yeah. I'd be like this too#I want to be majella when I grow up

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hilarious that my uncle remembered he's my godfather as soon I got published lmao

#Had to go to mass with my Dublin cousins and this irish American priest fella was going on about abortion#Pure weird out

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Let me just say shut the fuck up to my fellow Europeans saying shit about the US and how they expect it cause “welp it’s America”. This is a horrific fucking tragedy. How dare you make light of this. And we’re not better than them!!

First of all, there are European countries with just as horrific anti abortion laws and policies in place. The war on abortion is very much alive in Europe.

Secondly, when a change like this happens in a country as powerful and influential as the US, the pro-birth rats across the world are going to scurry at the chance to ride this wave. Our countries could be next, be careful and be vigilant.

#of course not to take away from the struggles of the us but just to say we aren’t necessarily safe from this either#roe vs. wade#America#ireland#irish#Europe#European#the eu#pro choice#abortion#roe v wade#feminism

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

9. Of the Pregnant Woman Blessed and Spared the Birth-Pangs

"1. With a strength of faith most powerful and ineffable, [Brigit] blessed a woman who, after a vow of virginity, had lapsed through weakness into youthful concupiscence, as a result of which her womb had begun to swell with pregnancy. In consequence, what had been conceived in the womb disappeared and she restored her to health and to penitence without childbirth or pain.

2. And, in accordance with the saying 'All things are possible to those who believe', she went on working countless miracles every day without ever proving anything impossible."

-Cogitosus, Life of Saint Brigit (translated by Sean Connolly and J.M. Picard, 1987)

This translation is in my personal files and I can send a copy to you upon request. If you want to thank me, consider a donation to The Brigid Alliance.

#Brighid#Brigid#Brigit#Bríd#Cogitosus#Cogitosus's Life of St. Brigit#Vita sancta Brigide#abortion#abortion miracles#protectors of women#justice goddesses#healing goddesses#Brigid of Kildare#Brigid of Ireland#Irish saints#Irish goddesses#Brighidine paganism#gabhaim molta Bríde#thank you Lady

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

#i really wish american Christofascists would stop trying to co-opt an irish identity on twitter#trying to spread their nonsense beliefs here like they did during the gay marriage and abortion referendum

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Irish women walk for abortion rights, 2016. (Photograph: Alastair Moore/London-Irish ARC.)

In May 2018, two-thirds of Irish voters opted to legalise abortion in a referendum pro-choice activists had long called for. A defining image of the campaign was of a march two years earlier outside the Irish embassy in London. “We wanted to make a visual statement that might reach decision-makers at home,” says Hannah Little (front). “We decided 77 women should walk silently with suitcases towards the embassy, the number of women then travelling from Ireland to Britain every week to access terminations.

“People who question if a protest accomplishes anything don’t see the butterfly effect: strangers meet, swap details, start a campaign. That’s exactly what happened here.” The London-Irish Abortion Rights Campaign met with MPs, launched legal cases, raised money for pro-choice causes, held protests and mobilised Irish voters abroad. “I don’t see myself in this photo at all. Oddly, I never have,” Little says. “I see young women who are angry and ready to take power back. It resonates with people because we look unstoppable. And we were!” GS

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

we have reached a point in the abortion debate where i just saw a tiktok where someone was like “well, of course, im not for late term abortions” and i went into a little solo a capella tune singing:

no ooone has a laaate term abortion for the craaaaic.

soon on spotify.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

I want to start going to the gym but to make that viable I have to eat more regularly but to eat more regularly I need space to store food but to have space to store food I need to move out but to move out I need money but to get money I need a better job but to get a better job I need to be mentally better but to be mentally better I need to start exercising and eating better but to exercise and eat better I need

#rambling#like do you get it. its a fucking trap and it feels like ill never get out#shoulda been aborted. too bad my moms an irish catholic bitch

1 note

·

View note

Text

swan upon leda are you kidding me T-T

#oh god this is going to be about sa and abortion rights isnt it#leda and the swan#william butler yeats#hozier#and yeats is irish too

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

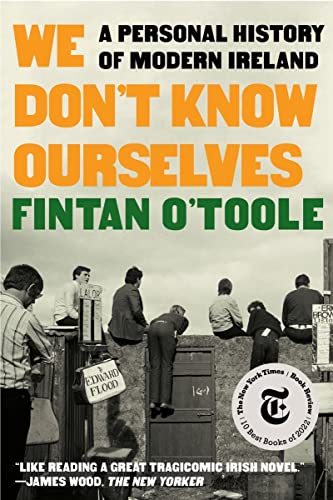

Book Review: We Don't Know Ourselves by Fintan O'Toole

Author: Fintan O’Toole

Title: We Don’t Know Ourselves: A Personal History of Modern Ireland

Narrator: Aidan Kelly

Publication Info: Highbridge Audio, March 15, 2022

Summary/Review:

Irish journalist Fintan O’Toole takes the Billy Joel approach to the history of his nation by starting with the year of his birth. In 1958, when O’Toole was born, the republic was lead by conservative veterans of the…

View On WordPress

#Abortion#Audiobooks#Autobiography#Book Reviews#Books#Clergy Sex Abuse#Emigration#Ireland#Irish History#Memoir#Politics#The Troubles

1 note

·

View note

Text

I'm going to start taking Irish seamoss supplements tomorrow and belly wrap Thursday... Because for the last year I've been struggling with the belly fat left after my abortions and finally took the time to Google correctly what I need to do about it so imma drink lots of water and cut out processed foods and try the seamoss and belly wrap wish me luck

0 notes

Text

Medicine for Sin: Reading Abortion in Early Medieval Penitentials

“The earliest penitential ruling on abortion takes us to early medieval Ireland. It originated in perhaps the oldest surviving penitential, Vinniani, composed in mid to late sixth century Ireland by a certain Vinniaus. A precise date is elusive, though clear use of Vinniani in a penitential attributed to Columbanus gives a reason to suppose that it was written before Columbanus’s departure for Gaul in c. 591.

Although Vinniani was not as directly influential as two other penitentials with Irish connections, Columbani and Cummeani, versions of the relevant rulings entered numerous later penitentials because of their inclusion in Columbani. In one sense, Vinniaus was writing in a monastic context. In a short epilogue Vinniaus explained that he had written a ‘few things about the remedies of penance’ for the ‘sons of his bowels … so that all evil deeds may be destroyed by all people’.

The overwhelming majority of Vinniani’s canons, however, applied to clerics or laypeople, suggesting that Vinniaus was writing with a mixed community including manaig or lay monastic tenants coalesced around a monastery in mind. After opening rulings on sinful thoughts and intentions, a sequence addressed violence and murder. Compared with subsequent penitentials, Vinniani had plenty of moralizing asides.

In one aside Vinniaus very carefully emphasized the extra responsibilities of the clergy compared with the laity. A layman received a lighter penance, Vinniaus reasoned, ‘because he is a man of the world, his guilt is lighter in this world and his reward less in the future’. Thereafter, the bulk of Vinniani addressed mainly clerical sins (Vinniani 10–29) followed by lay sins (Vinniani 35–47). This is our first strong clue to understanding the thought processes behind the relevant ruling.

Despite considerable interest in lay sin, including sexual sin, abortion was addressed in the clerical section. After dealing with clerical fornication in quite some detail, Vinniaus turned to magical practices. First he addressed a scenario in which a cleric or woman, a male or female malificus/a, in some way harmed (we will return to a semantically awkward Latin verb, decipere, in the section on Columbani below) someone through their maleficium. ‘It is an immense sin,’ he added, ‘but can be redeemed through penance’, six years in this case.

Next, if the offender (still by implication a cleric or woman) had harmed no-one but ‘had given [something] to someone out of dissolute love’, he or she received a whole year’s penance. The next ruling (Vinniani 20) was effectively the third in a triad on different forms of maleficium. The perpetrator, however, was now female: If a woman has destroyed someone’s offspring by her maleficium, she should do penance for half a year with an allowance of bread and water, and abstain from wine and from meat for two years and [fast] for six Lents with bread and water.

Breathlessness is an occupational hazard from the earliest penitential ruling on abortion. There are textual and semantic complications. My translation of Vinniani 20 is deliberately open: ‘If a woman has destroyed someone’s offspring’. ‘Someone’ could refer to a woman (as in another woman’s child) or to a man (as in a woman’s child by a man). It is likely that different readers read it in different ways.

The Latin text in Wasserschleben’s older edition requires the first interpretation: ‘If any woman has taken away [that problematic verb, decipere, again] the child of another woman [etc.]’. The difference stems from divergences between the two ninth-century manuscript witnesses to Vinniani. In Ludwig Bieler’s estimation the manuscript on which Wasserschleben based his edition better preserved the order of the original but is less reliable on wording.

Bieler justified his translation, ‘child she has conceived of somebody’, by pointing to the ruling which immediately follows: But if, as we have said, she bears a child and her sin is manifest, six years, as is the judgment about a cleric, and in the seventh she should be joined to the altar, and then we say that she can restore her crown and ought to don a white robe and be pronounced a virgin. This ruling assumed a spiritual, rather than physical, conception of virginity.

A woman could earn back her crown (corona), in other words restore her virginity. The rest of the ruling elaborated on the comparison with fornicating clerics, who would likewise be restored to their office after seven years. The rationale for the duration of penance, incidentally, was scriptural: a just man fell and rose seven times (Proverbs 24. 16).

Read on its own Vinniani 20 could have been taken in either sense outlined above. Moreover, reading partus as a young infant rather than a fetus (which is how partus was used in Latin versions of the Ancyran canon), by itself the ruling could have been read as covering infanticide. Taken together with Vinniani 21 on the lapsed virgin, however, Vinniani 20 implied getting rid of a child before the manifestation of sin through childbirth.

In relative terms, the penance in Vinniani 20 seems lenient: half a year on bread and water, and abstention from wine and meat for two years. The vowed virgin who did not kill her child, by contrast, received six years in total. Hugh Connolly has concluded that ‘Finnian did not accord to the foetus the same status as a human being after the moment of birth’. There is something to this. With some exceptions, penitentials tended not to treat abortion as severely as other offences, including homicide or adultery.

But conceiving fetal status too narrowly is misleading. For Vinniaus fetal status was inextricable from the circumstances surrounding conception and from the repercussions of birth.

Before the maleficium rulings Vinniaus scrutinized four permutations of what he called the ruina of fornication: clerical sexual sin. The key questions were habituation and social visibility. Like the virgin who lapsed, a cleric who fornicated lost his crown (corona). If his sin was an isolated incident which was ‘hidden from people but came before the attention of God’ it received one year of fasting. He would not lose his office because, Vinniaus added, ‘sins can be absolved in secret by penance’.

In the next scenario if a cleric habitually fornicated without its becoming public knowledge, his penance was three years and he lost his clerical office ‘because it is not a smaller thing to sin before God than before people’. But there were degrees of ruina. Fathering a child was the ruina maxima: ‘If any of the clerics has fallen to the greatest ruin and begotten a child, the crime of fornication and homicide is great, but it can be redeemed through penance and God’s mercy’.

This was the ruling to which Vinniani 21 later referred back. Intriguingly, the duration of penance was the same as the penance for the cleric whose fornication was habitual but not public knowledge, though Vinniaus stressed the quality of the penance, undertaken with tears of contrition, and prayers day and night. As well as losing his office in this case, the offending cleric would be exiled until the seventh year, whereupon he could be restored at the discretion of a bishop or priest.

There was one final permutation, a slightly rushed addition, which reemphasizes that durations of penance did not always operate according to a strictly calibrated calculus of moral gravity: ‘But if he has not killed the child, lesser sin but same penance’. Only one other ruling in Vinniani addressed children who were unwanted because sinfully conceived. Although it appeared within the section on lay sins, the ruling concerned puellae Dei, nuns.

A layman who ‘defiled a girl of God and she has lost her crown and he has begotten a child from her’ would do penance for three years, including no intercourse with his wife for the first year. The penance was reduced if the puella Dei did not bear a child. There was no mention of attempts to abort or kill such an infant.

The ‘ethical elite’ at the summit of early Irish Christian communities justified its position in part through its special sexual status. Disclosure of sexual sin through the birth of children to clerics or nuns undermined the hierarchical patterning of these communities. It is not surprising, then, that Vinniaus almost exclusively thought about children born of sinful conceptions in terms of clerics and nuns.

When addressing responses to the conception or birth of such children in the form of abortion or infanticide he did not address laypeople at all. The focus is telling. His penitential rulings on abortion and infanticide were shaped by questions of social visibility and community repercussions when the sexual sins of clerics or nuns became public knowledge.

Coincidentally, a rather different seventh-century Irish source, a precursor to one of the miracle stories with which this book began, handled the disappearance of children conceived in sin in a comparable way. In c. 680 Cogitosus, a monk of Kildare, wrote a vita of one of the most eminent early Irish saints: Brigit of Kildare.

One startling miracle motif concerned Brigit’s encounter with a pregnant nun: With a strength of faith most powerful and ineffable, [Brigit] faithfully blessed a woman who, after a vow of integrity, had fallen into youthful concupiscence, whose womb was now swelling with pregnancy; and, after the conception disappeared in the womb without childbirth or pain she restored her healthy to penitence.

The great temptation in the study of early Irish hagiography, especially Brigidine hagiography, is to excavate pagan fossils from Christian texts. On some readings this brief story offers a glimpse of ‘traditional heathen customs’ or even of Brigit the fertility goddess. More recently, Maeve Callan has argued that Irish pentientials and hagiography capture a ‘remarkably permissive attitude’ to abortion, and that ‘female abortionists in the penitentials … might be said to some extent represent the morality of “ordinary” Irish Christians’.

But the story’s dramatis personae and monastic context, and its appearance in texts which sought to promote Christian ideals every bit as much as Vinniani did, suggest we should resist drawing conclusions primarily about the pagan past or even lay contemporaries. Miracle stories often took the form of healing. In this case the affliction which needed healing was the problem of pregnancy for an individual and, by implication, a community defined by sexual renunciation.

Through her benediction Brigit managed to bring about the end of abortion without quite resorting to the means. Instead of the bloody effusion of abortion the conception simply disappeared ‘without childbirth or pain’, a reference to Eve’s curse in Genesis 3. 16. The miracle lay in averting the painful birth of an unwanted child together with the painful symbolism of having that child as a member of a community defined by chastity.

The apparent leniency of Vinniani 20 was the flipside of Vinniaus’s severity towards clerics who fathered or nuns who gave birth to children. It stemmed from the need to protect the sexual status which defined the spiritual elite in Christian communities. In a sense leniency did represent a position on the status of the fetus, but fetal status was evaluated in terms of circumstances of conception as much as embryological knowledge.”

- Zubin Mistry, Abortion in the Early Middle Ages, c.500-900

#early middle ages#medieval#abortion#irish#christian#religion#abortion in the early middle ages#zubin mistry

1 note

·

View note