#JÓN

Note

Would love to hear any thoughts on the codification of the poet-persona over time? 👀

Ok so in the spirit of the ask game, I am not checking any citations on this whatsoever, but if you want those lmk (though they uh. largely do not exist for rímur-poets specifically, because only me and Hans Kuhn have ever cared).

This is going to require some context because, as established, the number of living people who know and care about medieval rímur can be counted on my two hands. Probably without thumbs. So, rímur are a poetic form that developed in 14th cen Iceland, which look kind of ballad-y, in that they often use four-line stanzas with ABAB end-rhyme, though actually the ballad tradition in Iceland is quite distinct (on which, see Vésteinn Ólason, The Ballads of Iceland). End-rhyme was very exciting for Icelandic poets because it was only previously a thing in some uncommon types of skaldic metres, but rímur (as their name suggests) have end-rhyme as a defining feature and rapidly become The dominant form of poetry in Iceland until well into the 19th cen.

There are two very distinctive things about rímur, other than their metres: 1) they almost never tell 'new' stories; almost all rímur narratives are attested earlier in other forms, usually in prose, which can sometimes lead to the fun cycle of saga -> rímur cycle -> old saga is lost, new version is written based on the rímur -> more rímur are written based on the new saga -> repeat until the heat death of the universe; 2) as the form develops, it acquires introductory stanzas known as mansöngvar, a term which elsewhere usually means 'love poetry', although that's not really what they're doing here.

Mansöngvar are verses, sometimes in a different metre to the rest of the canto they're attached to, in which the poet speaks directly to the audience. In the medieval period, they're pretty short and often don't say more than 'look, I made you some poetry', but as time goes on, they get more and more elaborate, and the character of the poet begins to develop some quite distinctive traits. What's interesting here is that rímur were (certainly in the medieval period; less certainly later on) performed aloud, presumably by the poet, so there's definitely some questions to be asked about how accurate the poets' self-descriptions are when presumably the audience could go 'you're not pining away for love, Jón Jónsson, I've met your wife!'

So anyway, these mansöngvar are often linked to the medieval German Minnesänger tradition (er. The actual German word might be slightly different because I still don't speak German despite my PhD supervisor's pointed remarks), which is more overtly love poetry and which sometimes features the poet as an abject and despised lover of some cruel lady. This is something rímur-poets from the later medieval period and onwards have an incredibly good time with. You may be familiar with the story of Þórr wrestling with Elli, the personification of old age in the form of an old woman. There are at least two medieval rímur poets who have a whole extended passage about 'oh alas, when I was young I was a terrible flirt but now I'm old and no women like me, except oh no, I am being courted by this ugly old giant lady; Elli is the only ladyfriend for me now, wah'. it's very playful, it's very fun, it's drawing on this general sense that the poets put forward that they're poetically gifted, but romantically unlucky, which is kind of a Thing for poets across a lot of European literature (and probably more broadly, but I don't know much about that), and is especially pronounced in the earlier Icelandic sagas about poets, which usually feature poets failing to win the love of their life for various reasons (sudden attack of Christianity; sudden attack of magic seals; sudden attack of Other Guy With Sword; etc). So in evoking this, rímur-poets are situating themselves in this existing Image of the Ideal Poet, but doing so in a way that ties them into the specifics of the Norse literary/mythological tradition as well. Poets are also frequently old and tired (same, bro), and a statistically improbably number of them are also blind (although that might just be two guys we know about who were really prolific; most rímur are anonymous so it's hard to say. But it is perhaps convenient that this also links them to A Great Poet of Old, namely Homer).

The other thing that rímur-poets really like to bring up in their mansöngvar is the myth of the mead of poetry, which I will not recount here except to say that Óðinn nicked it from a giant, and also that some dwarves used it to buy safe passage off a skerry once, so it's poetically termed 'ship of the dwarves' because it's the thing that brought them safely across the sea. Every single medieval mansöngur, if one exists at all, refers to this myth in some way, even if it's just by having the 'I made you some poetry' bit use a kenning for 'poetry' that references the myth.* And poets have a lot of fun with this too! Iceland's a coastal community, they know about boats, so you get these extended metaphors about poets trying to board a boat to sample the mead of poetry and finding only the dregs because other, better poets got there first. Or they will describe the process of poetic composition in terms of ship-building: 'Here I nail together Suðri's [a dwarf name] boat'; 'Norðri's ship sets out from the harbour [= I'm about to start reciting the main bit now]'; 'the fine vessel has now been wrecked on the rocks [=I'm going to stop reciting now]'. They'll also speak of poetry as smíð, which means a work of craftsmanship, usually physical craftsmanship (obviously cognate with smithing in English), and of brewing the ale of Óðinn, so they're really into metaphors of physical craft when it comes to the intellectual craft of poetry, which I think is really neat.

*kennings = poetic circumlocutions, e.g. 'snake of the belt' is a sword because swords are vaguely snake-shaped and hang from a belt. Common poetry kennings are '[drink/liquid/ale/wine/mead] of [any of Óðinn's literally dozens of names]' e.g. 'Berlingr's wine', and the aforementioned 'ship of the dwarves' - poetic Icelandic has literally dozens of words for different kinds of ships and also literally dozens of dwarf names, so you can get a long way without repeating yourself.

So all these things that I've mentioned that poets like to bring up - old age, unluckiness in love, poets as craftsmen - become more and more tropified as time goes on, which in turn leads to these imaginative and extended reworkings of the metaphor. No longer can you just say 'I'm old and no one fancies me', no, it's 'My only assignations now are with Elli, wink wink, here's a long description of our date'. So you end up with this very codified image of The Ideal Rímur-Poet as an old man,* ideally blind, ideally unmarried, incredibly self-deprecating about his poetry, and because that's how everyone else talks, it's self-reinforcing.

*there is one (1) known female rímur-poet from the medieval period, the poet of Landrés rímur, who unfortunately didn't write many mansöngur stanzas but is doing her best with the 'unlucky in love' bit, although her lover (male) seems to have died rather than ditched her, which is a novelty.

Anyway, it's cool and weird and fun and as I say, only me and Hans Kuhn care, academically speaking.

#lol 1260 words here. which is. maybe 10 minutes of actual speaking time but OH WELL#asks I have answered#if there are bits that I haven't explained well lmk. I have a warped idea of how much the average person knows about Norse literary history#because I *am* on my Stan Rogers Wife Guy kick at the moment please imagine Jón Jónsson holding a guitar#also. lol. I am extremely fucking doxxable every time I talk about rímur so if you do know my full legal name. keep that shit to yourself.#but also. go read my phd thesis. if you like the shit jokes in this post you'll love 70k of them concealed in academese

32 notes

·

View notes

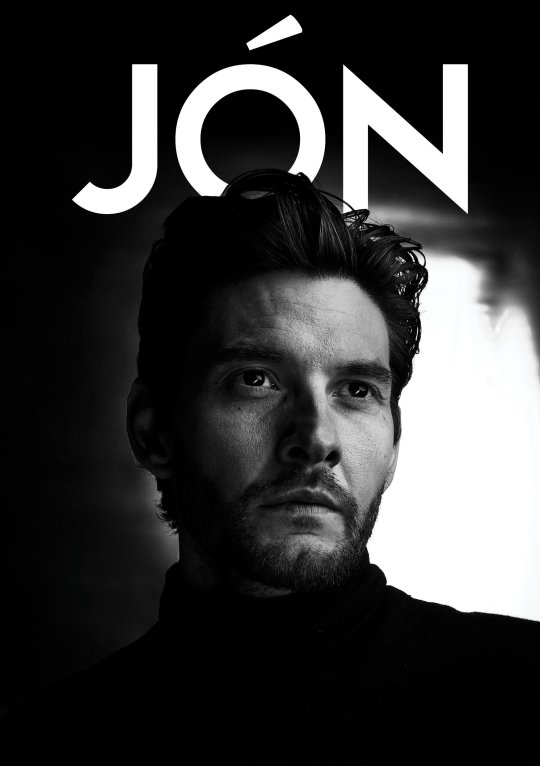

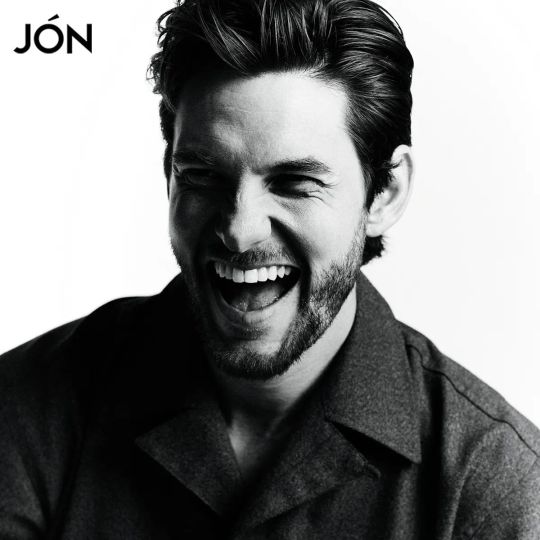

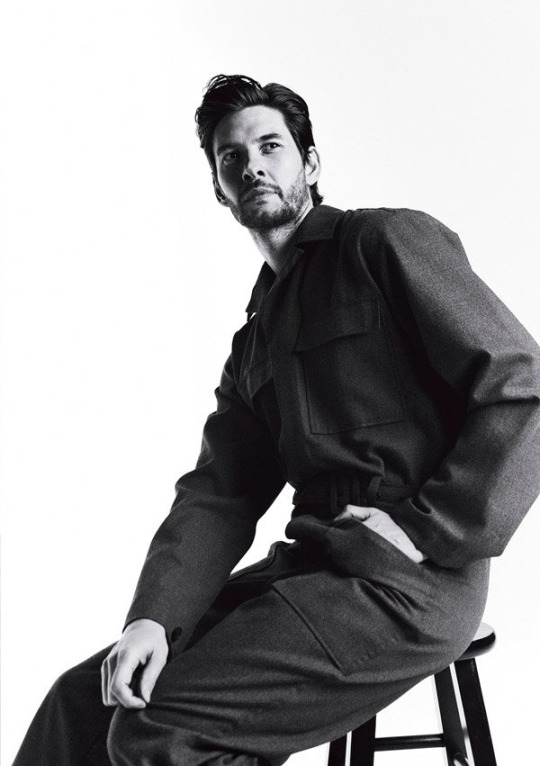

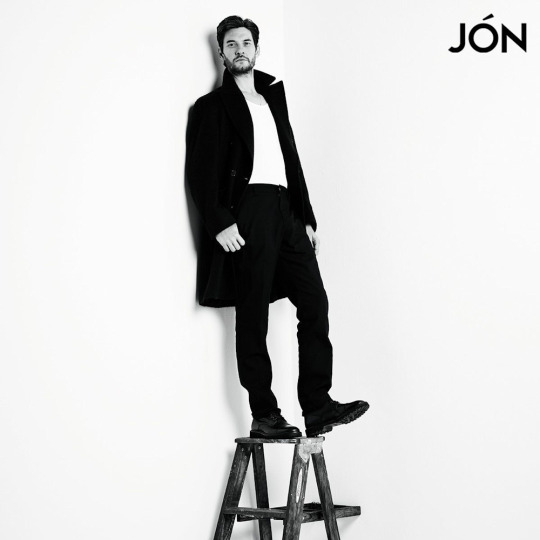

Photo

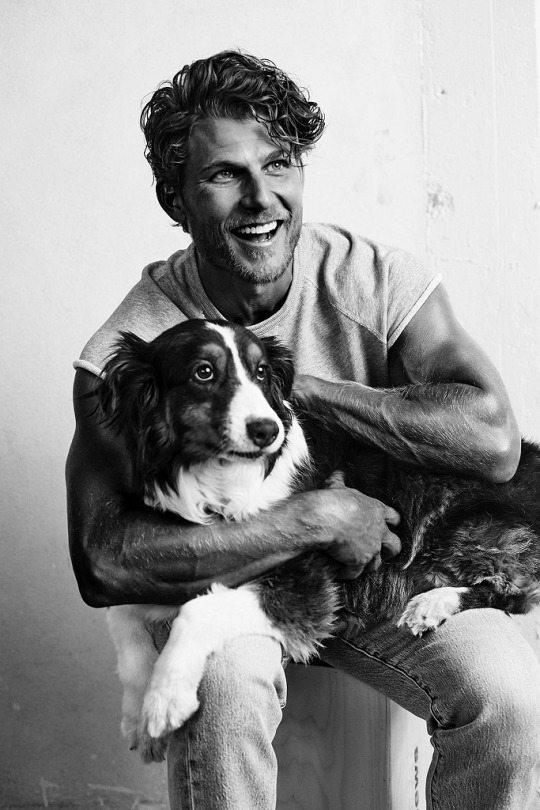

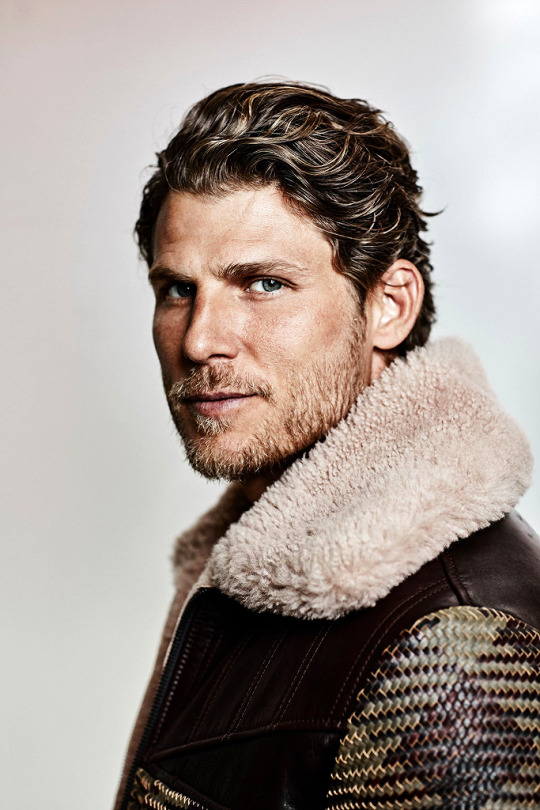

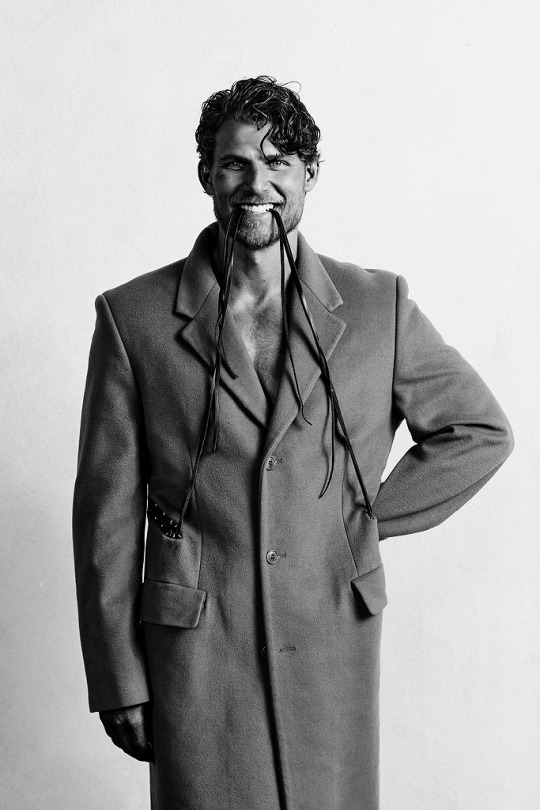

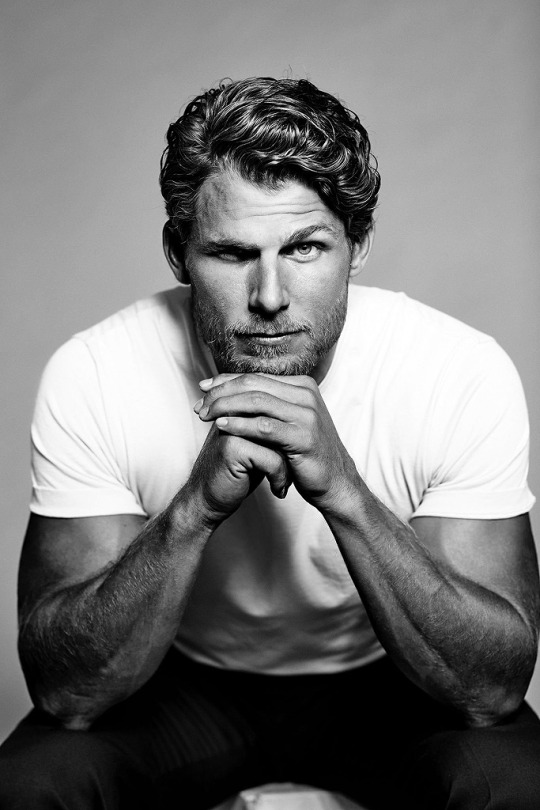

Travis Van Winkle by Leigh Keily for Jón Magazine (Oct. 2022)

576 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Her Fall From Grace by Sólstafir from the album Endless Twilight of Codependent Love - Video by Gaui H Pic and Faroe - Ice productions

#music#icelandic music#sólstafir#solstafir#svavar austman#sæþór m. sæþórsson#hallgrímur jón hallgrímsson#aðalbjörn tryggvason#birgir jón birgisson#music video#gaui h#ágústa eva erlendsdóttir#ragnhildur ásta ragnarsdóttir#hrafnhildur guðjónsdóttir#sigurboði grétarsson#jóhannes smári smárason#maría erlendsdóttir#diljá sigurðardóttir#gaui h pic#erin lynch#Youtube#video

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

can work its way so deeply into you that it’s pressed into the genes

What matters and has a lasting effect on you, deep feelings, difficult experiences, trauma, intense happiness; hardship or violence that cuts into your community or world, can work its way so deeply into you that it’s pressed into the genes, which then carry it from generation to generation – thus shaping those yet to be born. It’s a law of nature. Impressions, memories, experiences and setbacks are passed on from life to life, and, in that sense, some of us exist long after we’re gone, are even completely forgotten. So the past is always within us. It’s the invisible, mysterious continent that you sometimes feel when you’re half-awake. A continent with mountains and seas that constantly influence the weather and the shades of light within you.

— Jón Kalman Stefánsson, "Your Absence Is Darkness.” Translated by Philip Roughton. (Biblioasis, March 5, 2024)

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

( ) by Sigur Rós is Transfem

requested by @i-never-stoned-the-snail

#request#album#( )#transgender#trans#transfeminine#trans fem#transfem#sigur rós#Jón Þór Birgisson#Kjartan Sveinsson#Georg Hólm#Orri Páll Dýrason#post rock#art rock#ambient

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

“ La ragazzina con i capelli chiari sale sulla collina quasi tutti i giorni e il bisnonno racconta fiero che la figlia maggiore gioca con gli elfi. Dio aiuti quella povera bambina, dicono alcuni, allora lui si arrabbia oppure scoppia a ridere. Una volta la ragazzina torna a casa con un sasso dalla forma strana, sembra proprio un esserino, tutti intorno al tavolo lo studiano, se lo rigirano tra le dita, lei regala il sasso alla sorella più piccola, arriva la primavera e il cielo dissemina uccelli acquatici sulla penisola di Snæfellsnes.

Vanno ad Arnarstapi, il bisnonno lo definisce «un giro di compere in città» anche se città è un termine esagerato per questo gruppetto di case sparse. Eppure qualche volta il significato delle parole può cambiare a seconda di come le guardi, il che è un bene, vuol dire che esiste ancora qualche differenza tra le persone, tra i luoghi, vuol dire che c’è ancora un po’ di vita e di movimento nel linguaggio.

Per mio nonno e per la sua sorellina Arnarstapi è una città, una quantità impressionante di edifici. Lui ha quasi sette anni, lei quasi cinque e quell’anno trascorso sulla Snæfellsnes ha avvolto Reykjavík nella nebbia dell’oblio. Quando sei così piccolo i ricordi dell’anno precedente possono confondersi con i sogni. La figlia più grande fa una smorfia quando vede le sparute case di Arnarstapi. Il bisnonno parla con la gente, si informa, si presenta, la bisnonna fa compere poi va a passeggio con i bambini. C’è una casa un po’ distante dalle altre, come se cercasse di sottrarsi da qualcosa; una piccola casa di legno dove abita il capitano dai capelli rossi. Volevo dirti che non c’è bisogno che veniate da noi nelle prossime sei settimane, ci siamo riforniti di tutto il necessario con questo giro. Il capitano dice: ah sì, siete venuti a fare acquisti. È piccola e carina la tua casa, dice la bisnonna, è un po’ in disparte dalle altre. Mi piace stare al margine. Ah, ecco, bene, dice lei; in effetti non c’è altro da aggiungere, e lo saluta. Ma lui guarda i bambini e dice: in casa da me c’è un uccello con un’ala rotta, voglio farlo andare un po’ fuori, dopo.

Rimangono da lui per un’ora. A un certo punto la bisnonna e il capitano si ritrovano l’uno accanto all’altra, tanto vicini che le leggi perdono valore, tanto vicini che lei sente l’odore del pesce e del suo corpo caldo. “

Jón Kalman Stefánsson, Crepitio di stelle, traduzione dall'islandese di Silvia Cosimini, Iperborea (collana Gli Iperborei n° 330), Milano, 2021³, pp. 190-191.

[1ª Edizione originale: Snarkið í stjörnunum, Bjartur, Reykjavík, 2003]

#Crepitio di stelle#letture#leggere#libri#citazioni letterarie#Jón Kalman Stefánsson#romanzi#romanzo#Paesi nordici#letteratura contemporanea#nostalgia#passato#casa#ricordi#letteratura islandese#Reykjavík#Islanda#Iperborea#scrittori#letteratura scandinava#Jón Kalman#scrittori islandesi#luoghi#Snarkið í stjörnunum#poeti#narrativa#Silvia Cosimini#vita#ricordi di famiglia#antenati

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Passiamo l'esistenza alla ricerca di una soluzione, di qualcosa che ci consoli, che ci dia felicità e scacci tutti i mali. Alcuni intraprendono una strada lunga e ardua, e magari non trovano niente, a parte l'abbozzo di uno scopo, di una liberazione, o una forma di appagamento nella ricerca stessa, quanto a noi, ammiriamo nella loro perseveranza, ma ci è già abbastanza difficile accontentarci di esistere e prendiamo l'elisir invece di cercare, e continuiamo a chiederci qual è la via più breve per la felicità, e troviamo la risposta in Dio, nella scienza, nella grappa, nell'elisir che viene dalla Cina.

Jón Kalman Stefánsson - Paradiso e inferno

Ph Jason M. Peterson

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ben Barnes portada & photoshoot para JÓN Magazine UK

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Ma può essere complicato vivere perché a volte ti trovi di fronte a due possibilità e sono entrambe pessime, allora che si fa? Non importa quale scegli, dice Kierkegaard, le rimpiangerai entrambe.

E noi potremmo aggiungere: tu scegli un’opzione, e impari che a volte tra felicità e infelicità ci corrono solo due lettere. Non scegli nessuna delle due, e questo ti paralizza.”

Jón Kalman Stefánsson, La tua assenza è tenebra

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

cutting my palm and spilling my blood on some runes to make the pastor of Kirkjuból gravely ill

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Se mi dicessero di disporre in ordine di precedenza la carità, la giustizia e la bontà, metterei al primo posto la bontà, al secondo la giustizia e al terzo la carità. Perché la bontà, da sola, già dispensa la giustizia e la carità, perché la giustizia giusta già contiene in sé sufficiente carità. La carità è ciò che resta quando non c’è bontà né giustizia.”

Jón Kalman Stefánsson

28 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“EYJAFJALLAJÖKULL” (ICELAND)

JÓN VIÐAR SIGURÐSSON // 2010

#jón viðar sigurðsson#jon vidar sigurdsson#volcano#nature#black and white#monochrome#iceland#eyjafjallajökull#smoke#photography#u

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

È una benedizione e una condanna, vedere oltre, vedere di più degli altri che ti circondano, vedere un mondo più grande di quello che ti appare davanti.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Your Absence is Darkness

By Jón Kalman Stefánsson.

Design by Jason Arias.

1 note

·

View note

Quote

"Pedig valószínű, hogy igazából soha másról nem kellene írnunk, csak erről: bánatról, a fájó hiányról, a kiszolgáltatottságról és arról, ami néha két ember között történik, ami láthatatlan, mégis hatalmasabb a világbirodalmaknál, erősebb, mint bármely vallás, és gyönyörű, mint az égbolt; a könnyek áttetsző halairól és a szavakról, melyeket Istenhez suttogunk, vagy valakinek, aki nekünk a legfontosabb; a pillanatról, amikor egy nő magába enged, és a láthatár darabokra hullik. Soha másról nem kellen írnunk. Minden tanúsítványnak, jelentésnek, a világ minden üzenetének erről kellene szólnia:

Ma szomorúság miatt nem tudok bemenni dolgozni.

Tegnap megláttam egy szempárt, ezért ma nem tudok eljutni a munkahelyemre.

Sajnos ma nincs módomban bemenni, mert a férjem meztelen és lélegzetelállítóan szép.

Ma nem alkalmas, mert cserben hagyott az élet.

A mai találkozón nem tudok részt venni, mert itt odakint egy nő napozik, és a bőre szinte belülről izzik a naptól.

Ilyeneket persze sohasem merünk leírni; inkább beszélünk a villanysz��mláról, mint a két ember közötti villamos szikrákról, inkább a külsőt írjuk le, és nem a vér áramát, nem az igazságot keressük, a hirtelen felbukkanó verssorokat és vörös csókokat, hanem inkább a tények gépies felsorolásával leplezzük a gyengeségünket és a vereségeinket: a török hadsereg mozgolódik, tegnap mínusz két fok volt, a férfiak hosszabb ideig élnek, mint a lovak."

Jón Kalman Stefánsson: Az angyalok bánata

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gli occhi sfuggono a ogni controllo. Dobbiamo pensare a dove e quando li posiamo. L’intera nostra vita scorre attraverso gli occhi, e per questo possono essere fucili quanto note musicali, un canto di uccelli o un grido di guerra. Hanno il potere di svelarci, di salvarti, di perderti. Ho visto i tuoi occhi e la mia vita è cambiata.

Jón Kalman Stefánsson, "Paradiso e inferno", 2007

23 notes

·

View notes