#Jean Dieu de Saint-Jean

Text

#the duke of dalmatia's aides de camp#visual records of the aides de camp#visual records of the duke of dalmatia#alfred de saint-chamans#alfred de lameth#auguste petiet#brun de villeret#jean de dieu soult

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

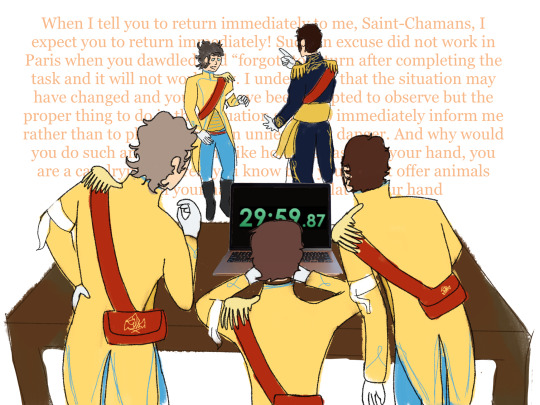

Presenting the Banana Boys the Aides-de-Camp of Marshal Jean-de-Dieu Soult, the excitable drunk collective blob military family of the grumpy asshole!

I’ve been enjoying reading about their shenanigans in @josefavomjaaga’s posts and wanted to draw them, especially as I’ve started having them appear in some writing snippets and RPs

From left to right we have

Alfred de Saint-Chamans, who once wondered why Napoleon was so interested in Soult’s ass and who thinks he deserves a medal too!

Auguste Petiet, who despite Soult being mean to him and not giving him a promotion because of a disagreement with Petiet's dad, is really proud of military daddy Soult

Alfred de Lameth, the jester who can't stop joking even when it offends Murat's wife and who got murked in Spain and made his fellow soldiers so sad they burned and slaughtered a village in revenge

Brun de Villeret, the sensible guy who got into a car crash because of Soult's distracted driving and who spent months trying to convince Napoleon that the rumours about Soult trying to make himself king in Portugal are mean rumours

I found references for all of them except Lameth, who died young and also his uncle is too famous so the image search is full of him and his stupid wig, so I pretty much just made up Lameth's appearance based on vibes.

There's more ADCs like Pierre Soult, the baby brother of Soult, Franceschi the Art Guy, Coco Lefebvre Who Physically Can't Stop Partying and others, but these four are probably the Main Characters in the writing I've done!

And also yeah Soult did decide that his assistants should be dressed in bright yellow shirts and sky blue pants.

#cadmus rambles#cadmus draws#jean de dieu soult#napoleonic wars#napoleonic era#alfred de saint-chamans#auguste petiet#alfred de lameth#brun de villeret#cad rambles about dead frenchmen on main

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Murat and Bessières at school

Still looking for something for @flowwochair, I came across this very brief remark in the memoirs of general Jean Sarrazin (more about him below):

When I was seven, my father took me to the college in Cahors, the capital of the Lot department. My father chose this college in preference to the one in Agen, on the advice of the Comte de Fumel, whose tenant he was. [...] I was raised with Murat, Bessières and Andral, with whom I was friends. Bessières was well-behaved, a little Cato. Murat was a scatterbrain, boisterous and concerned only with his own pleasures. He was a true Paris brat (gamin de Paris).

Now, I assume this author is a highly suspicious source. Not only because he, obviously, is yet another Gascon, but mostly because he, after having served in the Revolutionary and Imperial army, defected to the British in 1810, and supplied them with plenty of information on Napoleon’s plans and the most prominent leaders of his army. As a matter of fact, in 1811 he had a book published with descriptions of several prominent figures in France, called "The Philosopher", the first chapter of which is dedicated to Marshal Soult, who was probably the most interesting to the British due to him being their main opponent in Spain, and who in this book receives much more praise than is due to him. While much of it may be plain wrong or at least cannot be verified, I feel like it’s an interesting insight into what people in the army at the time thought about these folks.

Among other things, Sarrazin gives a long description of the battle of Fleurus, with some interesting twists. Mostly he claims that Lefebvre owed his reputation as a great general only to Soult, who at the time was his chief-of-staff, and even has general Marceau exclaim that Soult had won the battle of Fleurus for them. This is completely opposite to Soult’s own memoirs, where Soult has nothing but praise for Lefebvre’s actions during the battle of Fleurus, and barely mentions his own. However, there seems to be some truth to Soult coming to the aid of one rather desperate general Marceau, as Soult mentions this, too, though in a very different context.

The demand to detach some troops at a very inopportune moment is made in Soult’s memoirs as well – but not by Marceau, but by Saint-Just. And it’s not Lefebvre and Soult who refuse, but Jourdan (whom Soult praises a lot for having had the courage to stand up to what he calls "Saint-Just's presumptuous ignorance"). I am not sure in how far these memoirs are influenced by Soult’s own long life and his own political situation, but he clearly despises Saint-Just. According to his memoirs, the whole officers’ corps was shaking with fear while the politicians were with them, literally scared to death. In front of Charleroi, one artillery capitaine allegedly was executed for having failed to meet the schedule Saint-Just had set for him.

Again, I have no clue what this is based on. But I thought it worth mentioning, maybe somebody from the Frev community can shed some light onto this incident.

(Personally, I feel like Soult may be projecting here a little of "Joseph's presumptuous ignorance" onto another episode of his life 😋)

#napoleon's marshals#jean de dieu soult#battle of fleurus#1794#saint just#francois joseph lefebvre#jean baptiste jourdan#frev

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ruthless Representatives, Unjust Executions (1/3): the Death of an Artillery Captain

This is a response to @josefavomjaaga's recent post, which partially deals with the alleged arrest and execution of an artillery captain by Saint-Just, then a representative on mission, during the siege of Charleroi, and the representatives' abuse of military men around the time of the battle of Fleurus. Josefa enquired whether anyone could shed light on this incident from the FRev community. While I am not well-versed in FRev events, I would like to offer some of my findings about military justice in the army during the Revolution in relation to the representatives in three parts. The first part deals directly with the tale of Saint-Just's execution of the artillery captain, and how it was turned into a symbol that exemplifies the Revolution's extrajudicial violence. All translation errors are my own.

The source about Saint-Just's terrorisation and execution of the artillery captain that is cited the most is from Soult’s memoirs (1854). Writers, including Colonel Phipps, use this source verbatim without questioning it, because Saint-Just and all the representatives were obviously Stupid Civilians who thought that any incompletion of their orders amounted to betrayal:

It was above all the siege division which deployed with activity before Charleroi. The colonel Marescot directed the engineering operations, under the eyes of Generals Jourdan and Hatry; we had a sufficient artilery crew, and the representatives Saint-Just and Lebas stood at the foot of the trench to speed up the work. One day, they visited the site of a battery that had just been marked out: "At what time will it be finished?" asked Saint-Just of the captain responsible for having it executed. "That depends on the number of workers that I will be given; but we will work relentlessly," responded the officer. "If tomorrow, at six o'clock, she is not ready to fire, your head will fall off!..."

In this short time, it was impossible for the work to be completed; even though as many men were put there as the space could contain. It was not entirely finished when the fatal hour struck; Saint-Just kept his horrible promise: the artillery captain was immediately arrested and sent to his death, because the scaffold marched in the wake of the ferocious representatives. (pp. 156-157)

Saint-Just, in Soult's depiction, is the proper Archangel of Death, guillotining everything that stands in his path. In portraying Saint-Just thus, Soult criticizes the representatives' murder of an innocent man. Worse, he depicts representatives as civilians that can only stand around instead of hardworking soldiers bringing the siege to fruition, making their commands unjustified. Soult condemns the fact that a civilian's word could be the injust law that separated soldiers from life or death.

That said, as Soult is no friend of the political figures of the Revolution, his remembered account requires precise corroboration to be valid. I found one earlier source that describes, presumably, the same incident, from Victoires, conquêtes, désastres, revers et guerres civiles des Français, de 1792 à 1815, vol. 3. It was written in 1817 by "a society of soldiers and men of letters", and edited by Charles Théodore Beauvais de Préau, a general of the Revolution and Empire. Though this anonymisation may have been taken to avoid the wrath of the Bourbons in the Restoration, it means we have no idea who wrote the following section, nor their intentions:

This fierce man [Saint-Just], who never showed himself in the trench, informed that a captain of the first regiment of artillery had been somewhat negligent in the construction of a battery of which he was in charge, had him shot in the trench. At the same time, he gave General Jourdan the order to arrest, and consequently have shot on the spot, the General Hatry, commander of the besieging troops, the General Bellemont, commander of the artillery, and the commander Marescot. The General Jourdan had, at the risk of his own life, the courage to resist the wishes of this gutless representative. The officers of whom we have just spoken of had the audacity of protesting against the cruel sentence which condemned the unfortunate artillery captain Méras, and, in his his atrocious delirium, Saint-Just dared to accuse them of complicity. (p. 47)

If we infer from the title of this source that the editor compiled the accounts of his comrades, then this account was written by a former Revolutionary and Imperial officer who could have some memory of the incident. However, many aspects of this text don’t line up with Soult’s account, including the way the captain was executed (shot in the trench here, guillotined in Soult's account). Saint-Just's successive condemnation of high-ranking officers, which highlights how much power he had over even the highest echelons of the army, also does not appear in Soult's account. But we do have a name for the captain: Méras. His name, in fact, appears in a 1797 publication: L'observateur impartial aux armées de la Moselle, des Ardennes, de Sambre et Meuse, et la Rhine et Moselle, a memoir by Pierre Charles Lecomte, at the time "the conducteur general of the artillery in the Army of the Rhin-Moselle [sic]". This is his account on the affair, relegated to a footnote:

Before giving the details of the capitulation of Charleroi, I must cite a horrible feature of the role of Representative Saint-Just.

The French proconsul ordered the construction of a battery that he thought was necessary.*

The general Bollemont [sic] entrusted its execution to an artillery captain, named Méras. All the shovels, pickaxes, and other utensils happened to be employed in other work, the orders of the Representative could not be executed. The morning of the next day, passing close to the location where the battery was supposed to be constructed, he [Saint-Just] shouted, raged, sent to search for the captain; and, without listening to his reasons, he had him arrested. Two days later, when his [Méras’] company was battling against the enemy, he [Saint-Just] had him taken from the prison, he had him conducted to the middle of his works; and there, o misery! o inhumanity! he had him assassinated. At night his company returned to the camp covered in glory; they learned that their chief had been shot; they surrendered to despair. They wanted to go to the tyrant: they were stopped, under the fear that some of these brave soldiers would have become new victims. Méras was so much loved, that all of the artillery wanted to enact vengeance on his assassin. This almost universal rumour made itself heard amongst the trenches; and, for preventing it from having consequences, the company of the unfortunate Méras was sent into the interior.

*We know that there was a time when the Representatives, often little-instructed in the military arts, dared impudently to command old soldiers whose arms had dulled, and obliged them to sacrifice, according to their whims, some thousands of brave soldiers. (p. 38-39)

Once again, the details contradict even more with Soult’s account, and with that of the 1817 one. Soult says as much help as possible was given to the artillery captian, but Lecomte says all other workers were occupied and that captain received little help (presumably because the battery was militrarily unimportant). Méras’ misery is stretched out over two days instead of him being shot immediately, and it is not the generals who protested against Méras' execution that Saint-Just raises a hand against, but Méras' entire company, which the civilian government sends to the Vendée. The message could not be clearer: under "tyrannical representatives" like Saint-Just, the Revolution is eating its soldiers, the common people it was supposed to protect.

Is this the truth of the matter, since it is the earliest version? The publication is contemporary enough, but I am inclined to doubt the reliability of a text explicitly titled “impartial”. A look at the author's background reveals his attitudes. Lecomte was, according to BnF data, the maître de pension in Versailles until 1792 (presumably up to the abolishment of the monarchy), then the inspector of octroi taxes in Paris until 1815. Seeing that he served the First Empire, I am inclined to think that he was no die-hard revolutionary, and certainly not part of the Montagnard faction. Furthermore, he published his account after the fall of the Montagnards, during the height of the Directory. This makes the affair more likely to be Thermidorian propaganda, and indeed Lecomte even admits that his account was an “almost universal rumour”, not a fact, because in his story, no one is present at the scene of Méras’ death other than Saint-Just and his executioner. This makes the account unverifiable, and makes it more likely to be fabrication.

It would seem that, after Saint-Just’s death, the army’s fear and hatred of representatives turned into slander against their characters, often resulting in widely circulated variants of the same tale to emphasise different effects. The 1797 version highlights Saint-Just’s cruelties as a tyrant against the “small folk” of the Revolution and uses exclamatory language to amplify the reader's pathos. The 1817 version emphasises Saint-Just’s power over even the generals of the army, exaggerating his dictatorship. Finally, in Soult’s memoir, Saint-Just is not just a dictator who could dismiss soldiers with a wave of a hand. He and the representatives were synonymous with the guillotine and the excesses of the Revolution themselves.

The accounts of Saint-Just condemning Méras to death are inconsistent, and should amount to nothing more than invalid hearsay, which tells us nothing of the representatives' historical actions. If anyone has more information on the topic or the wider subject, feel free to add to this.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saint Jean de Dieu

#Art #Atypikal #Autisme #Chillout #Ecologie #Eubage #Funambulistière #Life #Lifestyle #Mars #Music #News #Ocean #Photo #Voyage #Youtube

Morphée semble de nouveau pleinement présent à sa tâche tant mon sommeil est long, mais empreint d’embûches lorsqu’il convient de m’en extirper tandis qu’Aurore aux doigts de rose m’appelle délicieusement de ses rayons lumineux.Heureusement, mon café Malongolien cassonadé est toujours un bon accompagnant pour me soutenir durant la première heure au sortir du lit.Concernant le déroulement de ce…

View On WordPress

#Art#Atypikal#Autisme#dailyprompt#Ecologie#Eubage#Funambulistière#Life#Lifestyle#Mars#Music#Music of the day#News#Ocean#Photo#Photo of the day#Random news of the day#Saint Jean de Dieu#The good life#Villefranche-sur-Saône#Voyage#Word of the day#Youtube

0 notes

Text

VOTE FOR A MARSHAL OF THE EMPIRE!!!

SINCE WERE NOT GOING TO APPEAR FOR AGES IN THAT OFFICIAL TOURNAMENT AND THE EMPEROR JUST GOT ROYALLED FUCKED THERE BY A VANISHED ROAST BEEF

HERES A BALLOT JUST FOR US MARSHALS OF THE EMPIRE!!

IN CASE YOU DONT KNOW WHO WE ARE WE'RE THE TOP MILITARY COMMANDERS PROMOTED BY NAPOLEON HIMSELF

AND WE HAVE REALLY BIG HATS

VOTE FOR WHOEEVER THE FUCK YOU WANT WHETHER THATS THE BEST OR THE SEXIEST OR THE MOST PATHETIC I DONT CARE

YOU KNOW YOU WANT TO VOTE FOR ME THOUGH!!!

GO AHEAD AND POST ALL THE PROPAGRANDA YOU WANT, THE ADC WILL SHARE IT IF ITS FUNNY

SORRY TO MONCEY, JOURDAN, BERNADOTTE, BRUNE, MORTIER, KELLERMAN, PERIGNON, SERURIER, VICTOR, MACDONALD, OUDINOT, MARMONT, SUCHET, SAINT-CYR AND GROUCHY, MAYBE WELL HAVE A PITY POLLE LATER

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

Friends, enemies, comrades, Jacobins, Monarchist, Bonapartists, gather round. We have an important announcement:

The continent is beset with war. A tenacious general from Corsica has ignited conflict from Madrid to Moscow and made ancient dynasties tremble. Depending on your particular political leanings, this is either the triumph of a great man out of the chaos of The Terror, a betrayal of the values of the French Revolution, or the rule of the greatest upstart tyrant since Caesar.

But, our grand tournament is here to ask the most important question: Now that the flower of European nobility is arrayed on the battlefield in the sexiest uniforms that European history has yet produced (or indeed, may ever produce), who is the most fuckable?

The bracket is here: full bracket and just quadrant I

Want to nominate someone from the Western Hemisphere who was involved in the ever so sexy dismantling of the Spanish empire? (or the Portuguese or French American colonies as well) You can do it here

The People have created this list of nominees:

France:

Jean Lannes

Josephine de Beauharnais

Thérésa Tallien

Jean-Andoche Junot

Joseph Fouché

Charles Maurice de Talleyrand

Joachim Murat

Michel Ney

Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte (Charles XIV of Sweden)

Louis-Francois Lejeune

Pierre Jacques Étienne Cambrinne

Napoleon I

Marshal Louis-Gabriel Suchet

Jacques de Trobriand

Jean de dieu soult.

François-Étienne-Christophe Kellermann

17.Louis Davout

Pauline Bonaparte, Duchess of Guastalla

Eugène de Beauharnais

Jean-Baptiste Bessières

Antoine-Jean Gros

Jérôme Bonaparte

Andrea Masséna

Antoine Charles Louis de Lasalle

Germaine de Staël

Thomas-Alexandre Dumas

René de Traviere (The Purple Mask)

Claude Victor Perrin

Laurent de Gouvion Saint-Cyr

François Joseph Lefebvre

Major Andre Cotard (Hornblower Series)

Edouard Mortier

Hippolyte Charles

Nicolas Charles Oudinot

Emmanuel de Grouchy

Pierre-Charles Villeneuve

Géraud Duroc

Georges Pontmercy (Les Mis)

Auguste Frédéric Louis Viesse de Marmont

Juliette Récamier

Bon-Adrien Jeannot de Moncey

Louis-Alexandre Berthier

Étienne Jacques-Joseph-Alexandre Macdonald

Jean-Mathieu-Philibert Sérurier

Catherine Dominique de Pérignon

Guillaume Marie-Anne Brune

Jean-Baptiste Jourdan

Charles-Pierre Augereau

Auguste François-Marie de Colbert-Chabanais

England:

Richard Sharpe (The Sharpe Series)

Tom Pullings (Master and Commander)

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington

Jonathan Strange (Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell)

Captain Jack Aubrey (Aubrey/Maturin books)

Horatio Hornblower (the Hornblower Books)

William Laurence (The Temeraire Series)

Henry Paget, 1st Marquess of Anglesey

Beau Brummell

Emma, Lady Hamilton

Benjamin Bathurst

Horatio Nelson

Admiral Edward Pellew

Sir Philip Bowes Vere Broke

Sidney Smith

Percy Smythe, 6th Viscount Strangford

George IV

Capt. Anthony Trumbull (The Pride and the Passion)

Barbara Childe (An Infamous Army)

Doctor Maturin (Aubrey/Maturin books)

William Pitt the Younger

Robert Stewart, 2nd Marquess of Londonderry (Lord Castlereagh)

George Canning

Scotland:

Thomas Cochrane

Colquhoun Grant

Ireland:

Arthur O'Connor

Thomas Russell

Robert Emmet

Austria:

Klemens von Metternich

Friedrich Bianchi, Duke of Casalanza

Franz I/II

Archduke Karl

Marie Louise

Franz Grillparzer

Wilhelmine von Biron

Poland:

Wincenty Krasiński

Józef Antoni Poniatowski

Józef Zajączek

Maria Walewska

Władysław Franciszek Jabłonowski

Adam Jerzy Czartoryski

Antoni Amilkar Kosiński

Zofia Czartoryska-Zamoyska

Stanislaw Kurcyusz

Russia:

Alexander I Pavlovich

Alexander Andreevich Durov

Prince Andrei (War and Peace)

Pyotr Bagration

Mikhail Miloradovich

Levin August von Bennigsen

Pavel Stroganov

Empress Elizabeth Alexeievna

Karl Wilhelm von Toll

Dmitri Kuruta

Alexander Alexeevich Tuchkov

Barclay de Tolly

Fyodor Grigorevich Gogel

Ekaterina Pavlovna Bagration

Ippolit Kuragin (War and Peace)

Prussia:

Louise von Mecklenburg-Strelitz

Gebard von Blücher

Carl von Clausewitz

Frederick William III

Gerhard von Scharnhorst

Louis Ferdinand of Prussia

Friederike of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

Alexander von Humboldt

Dorothea von Biron

The Netherlands:

Ida St Elme

Wiliam, Prince of Orange

The Papal States:

Pius VII

Portugal:

João Severiano Maciel da Costa

Spain:

Juan Martín Díez

José de Palafox

Inês Bilbatua (Goya's Ghosts)

Haiti:

Alexandre Pétion

Sardinia:

Vittorio Emanuele I

Lombardy:

Alessandro Manzoni

Denmark:

Frederik VI

Sweden:

Gustav IV Adolph

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

After the Cake Incident with Marshal Lannes, My assistant, Mlle. Hopster has been telling me to make a blog myself. I finally gave into her pestering.

I'll probably make a better introduction at a later date, as by then I'll have a better gist of Tumblr.

I am Baron Dominique-Jean Larrey, Surgeon to Emperor Napoleons Imperial Guard. Feel free to ask whatever you like.

-Larrey

( This blog is run by @hoppityhopster23)

(Disclaimers: This blog does not provide professional medical Advice, nor am i a professional historian. I'm just well read about the history of medicine and enjoy reading about Larrey)

(Pfp by @cadmusfly)

------------------

Tags:

Responses from the the Baron - answers to any asks.

Conversations with the assistant - Conversations with my time traveler assistant. shes the one who convinced me to create this. shes also young, sometimes foolish, and likes to give people bad ideas.

Portraits of the Doctor - Images of me.

Comments from the Assistant - self explanatory

-------------------

Fellow Soldiers and marshals, etc (personal notes below):

Marshals Other Military Staff Royals Other

@armagnac-army - My Dear Friend Lannes, Marshal of France, Prince of Siewierz, and Duke of Montebello.

@murillo-enthusiast - Jean-de-Dieu Soult, Marshal of France and Duke of Dalmatia. (I'm pretty sure he just tolerates me.)

@le-brave-des-braves - Michel Ney, Marshal of France, Prince de la Moskowa, and Duke of Elchingen. (He's very helpful, And I am grateful.)

@your-dandy-king - Joachim Murat, Marshal of France and King of Naples.

@chicksncash - Andre Massena; Marshal of France, Duke of Rivoli, and Prince of Essling.

@your-staff-wizard - Louis-Alexandre Berthier, Marshal of France, Prince of Neuchatel, Valangin and Wagram, and technically my boss.

@perdicinae-observer - Louis Nicolas Davout, Prince of Eckmühl, Duke of Auerstadt.

@bow-and-talon - Laurent de Gouvion Saint-Cyr, Marquis of Gouvion-Saint-Cyr, and a man I respect for giving the us Medical staff needed in life.

@general-junot - Duke of Abrantes, and General of the French army.

@askgeraudduroc - Also My good friend, Grand Marshal of the palace, Duke of Frioul, and head of the Emperors household.

@generaldesaix - One of my closest Friends. Unfortunately we didn't have a lot of time together in life. nut now we do.

@messenger-of-the-battlefield - Marcellin Marbot, an aide to an assortment of Marshals, and a man I met a few times in life.

@askjackiedavid - Jacques Louis David, neoclassical painter.

@carolinemurat - Caroline Murat, Queen of Naples, and sister of the Emperor.

@alexanderfanboy - Napoleon Bonaparte, Emperor of France.

@rosie-of-beauharnais - Josephine, the Empress of France.

@the-blessed-emperor - Alexander I, Tsar of Russia.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Toute guerre est sainte. La loi de la force est la seule loi au monde. S'il y a un Dieu, ce ne peut être qu'un combat."

— Jean Mabire, Ungern, Le Dieu de la Guerre (1973)

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Le bail du Graal dans Kaamelott me FASCINE you don't even know. C'est une forme de paganisme tellement méga poussée et pourtant les persos se considèrent christianisés. C'est trop intéressant pcq en plus, le syncrétisme bizarre présenté dans la série n'est même pas historique (mais alors PAS DU TOUT).

J'explique : le concept du Graal dans Kaamelott, c'est que cet objet est supposé être "la lumière pour tous les peuples," qui va apporter la vie éternelle et le salut aux hommes right? Càd les attributs de Jésus dans les évangiles; attributs qui lui sont exclusivement propres.

Ptit récap aux oignons pour ceux qui connaissent pas :

"En [Jésus] nous avons la rédemption par son sang, la rémission des péchés, selon la richesse de sa grâce." (Ephésiens 1:7)

"Jésus leur parla de nouveau, et dit: Je suis la lumière du monde; celui qui me suit ne marchera pas dans les ténèbres, mais il aura la lumière de la vie." (Jean 8:12)

"Au commencement était la Parole, et la Parole était avec Dieu, et la Parole était Dieu. Elle était au commencement avec Dieu. Toutes choses ont été faites par elle, et rien de ce qui a été fait n'a été fait sans elle. En elle était la vie, et la vie était la lumière des hommes." (Jean 1:4)

"Car il y a un seul Dieu, et aussi un seul médiateur entre Dieu et les hommes, Jésus-Christ homme, qui s'est donné lui-même en rançon pour tous." (1 Timothée 2:5-6)

"Il est lui-même une victime expiatoire pour nos péchés, non seulement pour les nôtres, mais aussi pour ceux du monde entier." (1 Jean 2:2)

"Car Dieu a tant aimé le monde qu'il a donné son Fils unique, afin que quiconque croit en lui ne périsse point, mais qu'il ait la vie éternelle." (Jean 3:16)

"Mes brebis entendent ma voix; je les connais, et elles me suivent. Je leur donne la vie éternelle; et elles ne périront jamais, et personne ne les ravira de ma main." (Jean 10:27-28)

On voit bien que 1) tout ça, c'est exactement comment les persos parlent du Graal, donc comme si c'était Jésus lui-même, et 2) y a rien dans le texte biblique qui permette que ces caractéristiques de Jésus soient conférées à un objet. Mais c'est intéressant pcq le sacrifice de Jésus est souvent, par métonymie, appelé son sang (versé pour nous). D'où la déformation possible - si on venait à prendre 'sang' littéralement, d'un coup on aurait besoin d'être en présence physique du sang de Jésus pour être sauvé, plutôt que d'avoir foi en son sacrifice. Et du coup, puisque le sang ne peut pas exister par lui-même, il faudrait chercher l'object qui l'a contenu. Et du coup, l'objet devient l'objet de la quête.

(Sauf que cette coupe qui contient le sang de Jésus ? Spirituellement, c'est n'importe quelle coupe utilisée pour boire le vin de la sainte-cène, càd le pain et le vin partagés entre chrétiens en souvenir du sacrifice. Luc 22:19-20. Le rêve d'Arthur, où il s'imagine que Perceval paume le Graal dans les coupes de la taverne ? Bah c'est plus proche de la Bible finalement. Mais comme le Graal, c'est ramener sur le plan matériel des réalités qui le transcendent, ça devient le recipient de la première sainte-cène littéralement utilisé pour récolter le sang de Jésus.)

Et du coup cette quête c'est la chose la moins chrétienne qui soit pcq :

- tu mets la grace universelle et sans limite du Dieu créateur dans un objet symbolique (définition de l'idolâtrie)

- tu remplaces un salut surnaturel et transcendant qui réconcilie les humains avec le divin par un salut matériel basé sur l'adoration d'une chose terrestre (la foi spirituelle est replacée par la religion/les rites)

- et tu prends un message clair et sans ambiguïté ('Jésus est mort et ressuscité pour le péché de ce monde, croyez et soyez sauvés') par une quête abstraite, apparemment impossible, 5 siècles après Jésus (donc personne n'a été sauvé entre temps, alors que sur la croix, Jésus a dit "tout est accompli").

Le Graal est flou, personne sait où il est, ce que c'est, s'il existe, même pas les dieux - ce qui est à l'opposé de Jésus, incarnation de la Parole (càd de la vérité/du sens/de la clarté). Rien dans le concept même du Graal ne colle avec la Bible. (Surtout pas l'interprétation d'Arthur, que Jésus est mort pour que tous soient coupables - pcq pour le coup oui, si la seule chose que sa mort donne à l'humanité c'est une Quête impossible pour le salut, Il a juste condamné tout le monde; sauf que c'est absolument pas ce qui est dit dans la Bible.)

D'où ça vient, alors ? Comment est-ce que cette croyance est apparue dans le monde de Kaamelott ?

Dans la vraie vie, l'apparition du Graal dans les légendes arthuriennes vient de fanfics de la mythologie celte mises à la sauce catho, mais ça s'est fait... au XIIème siècle !! (Plus exactement, le Graal lui-même est introduit au XIIème siècle, recyclé du concept irlandais du chaudron d'immortalité, et il n'est appelé une relique chrétienne qu'au XIIIème siècle.) Ce mélange est un énorme double retcon, en gros. Le Graal n'existait pas chez les celtes du 5ème siècle, ni en temps qu'objet de culte païen, ni en temps qu'objet païen adapté au christianisme.

Pareil avec le Saint-Suaire - la première fois qu'un texte quelconque en parle, c'est au XIVème siècle. (Fun fact : les clous, pas contre, y a des refs qui datent du 4ème siècle.)

Donc en gros, dans Kaamelott, les persos ont des croyances qui sont impossibles pour leur époque. Les anachronismes sont pas méga surprenants, vu par exemple la jeunesse d'Arthur dans une Rome des années 460 où le christianisme est à peu près aussi mainstream que le pastafarisme. Historiquement, Rome était officiellement 100% chrétienne depuis environ 140 ans. C'était plus Spartacus et Astérix.

Mais encore une fois, outre les anachronismes... le Graal vient d'où, dans Kaamelott ? Puisque dans la vraie vie, ce sont des chrétiens qui ont pompés des vieilles légendes celtes pour le créer, pas des celtes qui ont déformés leurs propres mythes quand leurs propres cultes existaient encore.

Pour moi, tout ce bazar justifie une interprétation clairement pas voulu par Astier - que 'in-universe,' on peut voir la Quête du Graal dans Kaamelott comme une invention par les dieux celtes non-sanctionné par le "Dieu unique," dans un pari désespéré pour que leurs cultes disparaissaient pas.

J'irais même jusqu'à dire qu'on peut défendre l'idée que Dieu est carrément contre et qu'Arthur a en fait deux destinées séparées : une avec Excalibur et le Graal, d'après les dieux celtes, suivant les lois et la morale celte, et une selon Dieu, avec la fidélité à Guenièvre notamment.

Pour étayer ça, y a le fait que la Dame du Lac - qui est très ouvertement celte, envoyée et porte-parole des dieux celtes - est une force moteur de la Quête du Graal sans jamais être capable d'expliquer pourquoi Dieu délègue. Y aussi que les ordonnances des dieux celtes, directement liées au succès de la quête, sont souvent à l'opposé exacte de la loi biblique (ex : Arthur commet une double faute en épousant Mevanwi et en l'épousant sans tuer Karadoc, alors que dans l'histoire de David, le plus grand des deux péchés n'est pas l'adultère mais le meurtre d'Uri, le mari de Bathshéba.)

Il y a bcp, bcp d'autres trucs, mais ce post est bcp trop long donc je détaillerai ça une autre fois.

23 notes

·

View notes

Note

🪄🪄🪄 you are a 🐉🐲 now 🪄🪄🪄

Suddenly, everything shifts. The ADCs look at each other, a little bewildered.

Saint-Chamans: Did you feel that?!

Petiet: Uh…

Brun: Nothing seems to have happened.

Lameth: Mass hallucination! Perhaps it was something like déjà vu, or presque vu? We have been working awfully hard~

Bory: Perhaps something strange has happened, and we simply didn’t notice it! Strange things do happen often in this exciting afterlife, often inexplicable - though nothing is inexplicable if we study it enough!

Brun: Saint-Chamans, weren’t you going to take the reports to the Marshal?

Saint-Chamans: Do I haaaave to? Fine, give those here-

Lameth: Good luck with the dragon, valiant Saint-Chamans!

———

Saint-Chamans: Your Excellency, I’ve got the scout’s reports here!

Hmmph.

The deep taciturn voice is heard not by the ear but by the mind. It carries the sensation of steely irritation with it.

The massive dragon reclines on a mat laid out on the ground, one of his prized paintings before him. His maroon scales catch the light a little as he shifts to stare at the aide-de-camp with a single golden eye the size of Saint-Chamans' head.

Let me read them.

Saint-Chamans can feel the heat as the dragon before him exhales. He used to be pretty intimidated by the idea of working for a dragon marshal's staff, but that hadn't stopped him from saying some pretty unwise things in the past - yet the Soult drake still seems quite fond of him.

Fond enough to ride his mind and read through his eyes, as is the covenant between dragons and those they feel possessive of. Saint-Chamans closes his eyes for a moment, opening his mind up to the beast before him, and feels a presence settle into his thoughts.

He opens his eyes which blaze gold now with the telltale sign of draconic possession, and through him, the dragon that would be named Jean-de-Dieu in another world reads his paperwork.

———

(( For the next few days, Soult and his ADCs will be convinced that this has been the way that this has always been. Welcome to the Marshalate Dragons AU!

More information + drawings on my main, but that absolutely isn't required reading. The important thing is that dragons are kinda psychic, they go comatose if they get injured or tired, they recover faster around their favourite treasures/people/places and can kinda possess them or hear their thoughts or other weird stuff, and they're like people but scaley.

And they breathe fire! ))

#event: marshalate dragons au#the duke of dalmatia's correspondence#anonymous#the duke of dalmatia's aides de camp

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

it is alleged napoleon on saint helena said jean-de-dieu soult should have been shot for his plundering

maybe he should also have been framed and and hanged on a wall.

high resolution stills under the cut.

babby's second animation

ended up keeping dithering on because the nondithered version had better colours but also did not play nicely with my shading fuck it

thanks to @impetuous-impulse for suggesting the pun on coupable (guilty) and coup (cut)!

happy birthday soult! im going to continue drawing and writing weirder shit of fictionalised you

oh yeah the french says "Je sais ce dont ils me jugent coupable." which the machine assures me means "I know what they find me guilty of" but possibly in a stilted/formal manner, welcoming suggestions/corrections though!

#jean-de-dieu soult#jean de dieu soult#napoleon's marshals#napoleonic wars#cadmus draws#cadmus animates?#the thing is that because lannes and soult are my favs i end up experimenting with lannes first and then refining the process with soult#need to redo the lannes body pillow to be better

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saint-Chamans about Soult and the "roi Nicolas" affair

So I did it. Here is the testimony of the public prosecutor's crown witness against "roi Nicolas Soult" 😁. Taken from Saint-Chamans' memoirs, translated to the best of my and DeepL's abilities. I'm posting this mostly for @cadmusfly but read at your own risk. As I warned before, this is very long, rather convoluted and may be quite boring. Also, of course I could not resist jumping in to defend Soult at several points.

[…] we advanced cheerfully towards the borders of Portugal, not doubting the success of our expedition; Marshal Soult, following the instructions given to him by the Emperor, flooded the country with proclamations, but we soon saw that they had little effect on a fanatical people who were exhorted by their priests to make a stubborn defence; the excesses, theft and bad conduct of the Duke of Abrantès's army during the first expedition had, moreover, stirred up all the Portuguese against the French name.

Saint-Chamans may not always be the sharpest knife in the drawer, but these observations of his are interesting. Napoleon ordering a flood of proclamations hints at an attempt to peacefully win over the population to the French side from the very beginning (an attempt that Soult would, in his mind, continue in Oporto with different means). It is to be noted that Portugal as a whole had already been occupied and for some time administered by Junot from late 1807 to mid-1808. There must have been a francophile party within Portugal.

While I am not much familiar with Junot’s occupation of Portugal and its "excesses" (@snowv88, do you happen to know if Junot's occupation of Portugal was in some way worse than what had happened in other countries before?), and while this may to a large degree just be Saint-Chamans trying to pass the buck by pointing his finger at somebody else, it is true that a whole bunch of generals who had belonged to Junot’s army during the first occupation of Portugal now were under Soult’s command, re-entering a country that already despised them (this would in particular be so for general Loison, nicknamed "Maneta" and hated with a passion by the Portuguese). Moreover, these generals, whom Napoleon had ordered Soult to take with him, now had entered Soult's staff as supernumerary members without specific duties. So not only did Soult have to take over an army corps that he had never commanded before (his own corps had remained in Germany), and men he did not know and who did not know him, but he also had to deal with a large group of bored officers, with lots of time on their hands to feel ignored or badly treated by their new commander-in-chief.

But I’m already digressing. What I wanted to translate was Saint-Chamans’ opinion of Soult’s alleged attempt to make himself king. Here’s another remark on what Soult’s state of mind may have been like, once the French had managed to enter Portugal and become master of at least some parts of the country. Saint-Chamans has just returned from a journey to general Franceschi, and had barely avoided getting killed in attacks by Portuguese peasants several times on the way.

I took care, when I saw Marshal Soult again, not to tell him about all the misfortunes of my last night: I knew that he became seriously angry when anyone tried to give him an idea of the dangers that accompanied the French in this dreadful country, and of the exasperation of the Portuguese against us; he was extremely persistent in his resolutions and in his undertakings, and he was very annoyed with those who tried, either directly or indirectly, to divert him from them and to make him see the disadvantages. He could not, however, conceal them from himself for long, and this knowledge of his dangerous position threw him into false and hazardous political steps, the gist of which has never been properly grasped and which perhaps only he could have fully explained; but I will speak at greater length about this circumstance in a moment, and I will say frankly what I have seen and what I believe.

Which he then does some pages later, after having related the horrible scenes during the capture of Oporto:

Indeed, despite this brilliant victory, our position was very critical; the army of Sir Arthur Wellesley (since so famous under the name of the Duke of Wellington), 30,000 strong and united with the Portuguese army, was in Lisbon and preparing to march on Oporto; they were commanded by the Portuguese General Sylveira and the English General Sir Robert Wilson (the same man who has since been tried in Paris for having helped escape Lavalette). These latter corps were intended to intercept any communication with Spain.

Here, I believe, Saint-Chamans makes a rather dishonest argument, or at least argues in hindsight, because I do not think the French at the time were even aware of the strong British presence in Portugal. They only figured it out when they tried to go south from Oporto.

If Marshal Soult had not been absorbed by ideas of ambition, which dominated all others in him at the time, he would have realised that his position was untenable and that he had only one course of action to take: to regard Oporto as a conquest which he needed to take advantage of to feed his army well for a fortnight and recover from its fatigues; then to retreat with all his forces to the Minho, to seize Valença, a fortified town in Portugal, on this river, opposite Tuy, of which he would have made an excellent bridgehead which would have communicated from one to the other of these last two towns; he would thus have linked up with the corps of Marshal Ney, whose headquarters were in Coruña, and whose troops occupied Tuy and Santiago; in this way, he could have safely evacuated his wounded and sick to good hospitals established in well-closed towns, instead of being obliged to abandon them to the fury of the Portuguese, as he did when he hastily evacuated Oporto; he would have kept all his artillery, lost at the same time; he would make the part of Portugal between the Minho and the Douro his tributary; he would re-establish direct communication with the French army in Spain and France; his own army, which numbered only 24,000 men, would have lived in abundance; he would preserve for the French army the best entrance into Portugal for the time when they would have been in a position to conquer this country, and until then he could wage a war of exploration there [...].

While it is quite possible that this plan, developped by a Saint-Chamans writing some 15 or 20 years after the events, could have proven successful (even if it does assume that Wellesley would just have watched the French gaining a secure foothold in the country and puts a little too much faith into the forces of Ney who barely was able to hold onto Galicia at this point), it was unfortunately not at all in accordance with the orders Soult had received from Napoleon. These orders simply stated that Soult was to march into Portugal from the north, conquer it and seize Lissabon, for which Berthier in his last dispatches deemed Soult’s single corps sufficient. But if he really needed support, he should receive it from Ney (from the north) or Victor (from the east). A retreat however, by giving up an important city that had been conquered, was simply not an option.

And so Soult, sticking to his orders, remained in Oporto and tried to contact the two corps that were supposed to support him: Ney and Victor (by sending Loison east to Amarante, as we will hear). Unfortunately, both of them had their hands full with problems of their own, Ney had lost contact with Madrid himself, Victor never showed up and may not even have fully understood what he was supposed to do, and since by now Joseph in Madrid was in charge, who paid little attention to what was going on in Portugal, Soult was left utterly alone.

Continuing with Saint-Chamans’ account:

[…] But all these considerations were not in harmony with Marshal Soult's plans, and so he did not give them a second thought. No sooner had he established himself in Oporto than he began to unmask his plan; an officer, half-French, half-Portuguese, named Laffitte, a schemer if ever there was one, who had been sent to his staff for the expedition to Portugal, ostensibly as an interpreter, for he spoke Portuguese fairly well, but in reality as a spy, was his main agent with the Portuguese in this circumstance; at Oporto, this wretch discovered a Portuguese priest named Veloso, who was as rich as he was narrow-minded, and who was promised heaven and earth, provided that Marshal Soult became King of Portugal; at the same time, this ignorant priest was persuaded that he was not a bad man, and that all this was for the greater good of his country; he believed it, and this idea, combined with the fine promises made to him, made him one of the Marshal's most zealous supporters; he acted accordingly. He addressed the people in the streets and public squares; he preached in the churches, he spread money to make supporters for the Marshal, and led by the advice of Laffitte, he succeeded in giving this party, in Oporto and the surrounding area, a certain stability; deputations arrived from Braga, Guimaraens, Olivera, and other towns of which we were the masters, and where part of the population had returned to, soliciting the Marshall to ascend the throne of Portugal; registers were opened in the town of Oporto to receive the votes of the inhabitants, the number of which was very considerable, and General Ricard, Marshal Soult's chief of staff, who had been his aide-de-camp, wrote circulars to the divisional generals insinuating the matter, for the Marshal, despite the affection for him of the good inhabitants of his good cities of Oporto and Braga, felt that he could do nothing without the consent and cooperation of the French army.

So, this is the main testimony that modern historians base their accusation on when it comes to Soult and the »roi Nicolas« issue. Admittedly, it is a damning one. Saint-Chamans obviously is convinced that Soult really wanted to seize the crown and was intriguing on his own behalf, and his testimony carries particular weight, as, being Soult’s aide-de-camp, having his marshal’s trust and being in his inner circle, Saint-Chamans was in a position to witness everything that was going on in Oporto at close quarters …

While all this intrigue was going on, I was on a mission twelve leagues from Oporto near generals Loison and Delaborde […]

Oh. Or maybe he wasn’t.

So, what Saint-Chamans relates above is not something he has witnessed himself, it is what he has heard during the time he spent with generals Loison and Delaborde – who would later be among the main gossips about precisely this topic (Thiébault seems to have gotten the story from Loison; Delaborde, as to him, apparently backpedalled somewhat on his accusations when he was called upon directly to testify). But I’m sorry, I have interrupted Saint-Chamans again:

While all this intrigue was going on, I was on a mission twelve leagues from Oporto near Generals Loison and Delaborde who, with an infantry division and some cavalry, were charged with taking Amarante, and especially the bridge there (over the Tameyra); Marshal Soult announced loudly that, from there, this head of column would move towards Zamora, in order to communicate with the French army in Castile; but he was too good a military man to seriously entertain this project; if he had really wanted to communicate with French troops, it was towards Galicia, where he positively knew that Marshal Ney's corps was, that he would have manoeuvred; he had only twenty leagues to go, and he would have found himself opposite Tuy, which was to have been occupied by the French of Marshal Ney's corps.

Whenever I reflected on the military movements of Marshal Soult in this circumstance, I became convinced that he did not want to communicate with the French army in Spain; above all he wanted to avoid all relations with Marshal Ney, whose enmity against him and violent character he knew: he had every reason to believe that this Marshal would hasten to say loudly and to write to France that he, Soult, had sacrificed the interests of the Emperor and of the army to his personal ambition in this circumstance; and this is what did not fail to happen.

A few days after our entry into Oporto, I had been sent to Amarante; I had come back for a while, and then returned a second time; there was still only vague talk of the Marshal's plans; [...].

Leaving out the relation of poor Lameth’s death of which Saint-Chamans heard at this time and which moved him profoundly.

These reflections, which struck me even more on learning of his death than at the time I am writing these lines, had inspired in me a certain distaste for the military career and the uncertainties it presented; moreover, the grief I felt at having been for several months without any news of my family or my country added to my gloomy mood; I imagined that the greatest happiness I could aspire to in the future was to return to France and live there peacefully at home.

These »dispositions moroses«, the gloomy mood Saint-Chamans alludes to, in my opinion is also not to be disregarded. Saint-Chamans hardly was the only one who felt that way, this rather may have been the general feeling of the whole army, including its marshal. The men were alone in a hostile country, barely holding out, without instructions, support or clue what to do next.

It was in these circumstances that I returned to Oporto; there I found Marshal Soult completely immersed in his political combinations, and seemingly little concerned with military events; I wanted to ask him about this several times, but he always stopped me by telling me that in Portugal it was from his office that he was waging war.

It was hardly the time, but I was so accustomed to seeing him as a very superior genius that, from his apparent tranquillity, I still had the good faith, in this alarming crisis, to hope for a favourable outcome.

Here again I can’t help but wonder if, at the time, Saint-Chamans really saw an »alarming crisis«, or of he was writing in hindsight.

But his actions were becoming so ambiguous that we didn't know what to make of them ourselves, and one day when we were joking about it at the table of the aides-de-camp, all of us young men who liked to laugh, we distributed the great offices of his court among ourselves; I was immediately named grand equerry, because of all his aides-de-camp, I was the one who knew horses best and had served most in the cavalry; another was grand chamberlain, that one grand veneur, etc. Finally, we laughed and joked a lot about this subject, because despite what we saw and heard, none of us could imagine that such an absurd project as that of making himself king of Portugal had seriously entered the mind of the Marshal, that until then we had seen so sharp.

Here Saint-Chamans kind of confirms my suspicion that much of what he writes in his memoirs is argued in hindsight. At the time, the rumours apparently were there, but were seen as so ridiculous by everyone, including Saint-Chamans, that they merely served to amuse Soult’s (as usual very outspoken and exuberant) ADCs over supper. If they had truly taken the allegations serious, would they not have needed to take measures, to at least talk to Soult's chief-of-staff about it?

This table talk caused a stir in the army; the staff officers who were present, the officers on guard duty, even the servants, commented on it; I think that this conversation (1), reported to the Marshal by his associates, gave him food for thought, and a few days later he sent for me in the afternoon and took me for a walk with him in an orange garden where he sometimes went to relax from his work in the cabinet.

Footnote (1) seems to be a remark by Saint-Chamans himself that I am not quite sure how to translate:

On nous en fit un crime en France. - One turned this into a crime of us in France. (We were made to feel like criminals because of it? - By whom? Soult? Napoleon? And when? Most of the guys joking at that table would not return to France for years?)

We were alone, and he wasted no time in starting up a conversation: he had made the right choice, for I have never known how to make courtship at the expense of truth; he knew that better than anyone, and perhaps that was why he had chosen me.

He got straight to the point: - What do they say about me here?

- I've only been back a short time, but I'm hearing everywhere that you want to make yourself King of Portugal.

He looked at me fixedly, but without appearing surprised or angry; I remained cold and did not give him the explanation he seemed to be expecting, because I wanted to be questioned; that's the way to avoid saying more than you're being asked.

- I can imagine that, he continued. But why was I sent here? why was I put in the awful position I am in now? I can only get out of this by dividing the Portuguese amongst themselves, and to do that I am using the best political means in my power, because I have no money to throw at them.

- Do you think, Marshal, that these means will not be misinterpreted in the Tuileries, and that they will not try to frame you as a criminal?

- You're right, but I repeat that I have no other way of getting out of this, and the Emperor will do me justice.

After a few moments of silence, during which he seemed painfully agitated, he added:

- There will be many more cries in France when it is known that I tolerate the inhabitants of Oporto continuing their trade with the English, when people can say that I myself sell them wines, as I am currently trying to sell them some of those we took on our way here.

- There is no shortage of people in France, or even in Spain, I would say, who, in order to harm you, will represent these steps in very black colours.

- I'm expecting it, he continued in a sort of violent despair; I may have to put my head on the scaffold, but when I go up there, I'll have the consolation of telling myself that I've done all that I could to save 20,000 Frenchmen from the sad position to which they are reduced! Do what you must, come what may.

It was one of his favourite maxims, either because it was truly in his character, or because he wanted to persuade people that it was the rule of his conduct.

We had reached this point in our conversation, which could have become interesting, for he was ready to be trusting and I to talk, something that did not happen to both of us every day, and I was beginning a question about his military movements, to ask him why he was not setting off to cross the Minho again, when we were joined, at the bend in the path where we were walking, by General Ricard, who was coming towards us with a bundle of papers: These were urgent reports from the generals commanding our outposts at various points; the Marshal returned to give orders, and our conversation ended there; I never took it up again with him on this subject.

Which, my dear Saint-Chamans, is a shame.

The idea that I have formed of Marshal Soult's conduct in this circumstance has always been that he wanted to be asked to be king of Portugal by the inhabitants of the part of this country of which he was master; that then, having taken this first step, he would have solicited the votes of the army that he commanded; these would have been recorded in registers for each corps or staff, and he would then have placed all these documents before the Emperor, asking for his approval and making him aware that this was the only way to keep the Portuguese in the interests of France; perhaps in this way he would have succeeded, at least for a while, in his plans.

Whereas the idea that I get from this relation is that:

Saint-Chamans heard all the malicious rumours from Loison and Delaborde, but, being Saint-Chamans, did not think much about it.

Back at headquarters, Saint-Chamans immediately shared the stories he had heard with his fellow ADCs, who found them hilarious and joked endlessly - and loudly - about them during the all-night-party they held on account of Saint-Chamans's return.

An exasperated Soult, informed of what his aides had been up to this time, called for Saint-Chamans (whom he genuinely liked) in order to set him straight, but was interrupted by daily events.

Some twenty years later, when Soult had thrown in with the July Monarchy and supported Louis Philippe, thus - in Saint-Chamans's mind - breaking his vows to Charles X and the older branch of the Bourbons, Saint-Chamans decided that Soult had been an ambitious egotist all along, and wrote his memoirs accordingly.

But that's me. As I said, I am hardly unbiased. It is, however, interesting that Saint-Chamans, despite this event, would not break off relations with his marshal. And also, that we have another ADC, who in his memoirs states just as clearly that all these rumours were bullshit. That aide would be Petiet - not always well-disposed towards Soult, but in this case ready to defend him against all accusations. But I have rarely seen Petiet's testimony taken into account.

Make of it what you want 😊

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ruthless Representatives, Unjust Executions (3/3): Jourdan on the Death List

This is an addendum to the previous two parts of the series, which is in response to @josefavomjaaga's original post about Soult's account on Saint-Just condemning execution an artillery captain. In that post, Josefa also mentions that Soult talks about a proscription list Saint-Just had drawn up in case the French suffered defeat at Fleurus, including the commander-in-chief Jourdan and Soult himself.

I am suspicious of Soult's claim that Saint-Just had a death list he would enact in the event that Fleurus went badly, much less one with Soult's name on it. I doubt Saint-Just even acknowledged that Soult was a political threat, though the only evidence I have of this is the dearth of Soult in vol 2 of. the Œuvres completes of Saint-Just. Soult's name does not show up once, not even for promotion or praise; only that of his commander Lefebvre does. Soult's anecdote, however, led me to look into Saint-Just's correspondence with Jourdan, the other named member of this proscription list, and examine the veracity of Soult's statement regarding Jourdan. All translation errors are my own.

I think official correspondence, where one is required to be formal, rarely proves the emity between two parties unless they were spectacular rivals. That said, one would think the cordial tone Saint-Just uses when writing to Jourdan, then commanding the Army of the Moselle, would make Jourdan's inclusion in the proscription list dubious. Here is a letter of 8 priarial an II/27 May 1794, where Saint-Just broaches the idea of besieging Charleroi:

The representative of the people of the Army of the Nord to General Jourdan, commander-in-chief of the army of the Moselle.

I received your various dispatches. I pray that you continue to regulate your movements with this [Saint-Just's] army; we are still following the river Sambre, today our camp occupies the Tombe. We will try to seize Charles-le-Roi; you will take, without doubt, Dinant; then a corps of the army, which we will form at Maubeuge, will march on Mons, and another on Brussels.

I embrace my dear colleagues [representatives] Gillet and Duquesnoy. (p. 418)

It is impossible to deny that Saint-Just is domineering in this letter, daring to order Jourdan to do this and that when he has no military experience to justify it. Some writers, like Colonel Phipps in his series The Armies of the First Republic..., have interpreted this kind of civilian "meddling" as Saint-Just setting Jourdan up to fail. If so, the lengths Saint-Just goes to do so is odd. In Saint-Just's Œuvres, in a post-script to the letter to the Committee of Public Safety in Paris (pp. 419-420), Saint-Just mentions that he is writing to Jourdan every other day. He may have known nothing of soldiering, but being so hands-on with his correspondence implies he is rather anxious for Jourdan's success instead. (This is not to say he did not clash with Jourdan as Saint-Just tried to command him on military matters.)

Furthermore, Jourdan had survived as a commander of the Nord without death or disgrace. The Committee had already had a chance to behead him when they drew up a dimissal and arrest warrant for him. Instead, they ended up letting him go with a pension, indicating they still had trust in him.

It is also telling that, when difficulties occurred during the Siege of Charleroi, Saint-Just did not threaten Jourdan with arrest immediately. Once again, I reference Fischer's study of Jourdan during the Revolution. Fischer recounts that the revolutionary army suffered a defeat in 16 June 1794 during an Austrian army counterattack, because Lefebvre had run out of ammunition, pulled back, and Jourdan was forced to retreat (pp. 208-211). The revolutionary army suffered an estimated 3,000 to 4,000 casualties. To quote Fischer on what happened next:

Jacobin General; Jean Baptiste Jourdan and the French Revolution; 1792 - 1799. (Volumes I and II).

Jourdan's meeting with St. Just that night could not have been terribly pleasant. Although he promised the Committee that the army would take its revenge, a defeat was a defeat. Typically St. Just wanted to resume the offensive the very next day. Jourdan wished to rest the army for a few days, allowing them to replenish their provisions and ammunition. He also wished to attack elsewhere, because he was not happy with the tactical problems involved in besieging Charleroi. While he was ready to renew the offensive immediately as St. Just desired, he wrote that they "could do so more advantageously at another point." He promised to confer with St. Just and the other representatives to decide what to do. But St. Just and his colleagues were determined to continue to attack in the Charleroi sector. They granted Jourdan twenty-four hours to rest the army, and then the offensive was to recommence. (pp. 211-212)

Saint-Just, though portrayed by soldiers as guillotine-happy, did not "blow up" and condemn anyone for this seemingly random defeat. In this passage, Saint-Just does try to command Jourdan to do his bidding, but he is also capable of compromises. Lefevbre, partially responsible for the defeat, also seems to receive no consequential punishment. If Saint-Just wanted to accuse reluctant generals for cowardice and scapegoat someone for this setback, who better than Lefevbre and his chief-of-staff Soult, whose men somehow ran out of ammunition? As it stands, neither of their careers were affected by this incident.

In addition, at what points were officers more likely to be thrown in the brig or mount the scaffold? If the representatives wanted manpower, then we should note that officers were not universally condemned after a campaign when they could be substituted, nor were all the arrested universally executed. Even if they were dismissed, they could later gain employment. I think because the exceptions made more of an impression, the circulation of the executed officers' fates among the army exaggerated the (undeniable) injustice of the revolutionary military system.

In the end, after the success of Charleroi, Saint-Just gave credit to officers where it was due. While rumours swirled about Saint-Just condemning artillery captain Méras to death and threatening arrests of officers, he praised various officers, including Marescot of the artillery, in glowing terms to the Committee of Public Safety. As the Œuvres present:

On the 28th of last month, the army marched, one hour from the beginning, to meet the enemy; the enemy, at the same time, was marching on us. We met. The fog was thick; the fighting was terrible until three o'clock in the afternoon. The left, commanded by the brave General Kléber, worked wonders; general of brigade Duhesme distinguished himself there.The center fought the same way. General Dubois charged at the head of the cavalry, took five hundred prisoners, took seven pieces of cannon, and massacred seven to eight hundred men. The vanguard, commanded by General Lefebvre, had equal success and showed the same courage. A battalion of grenadiers charged the enemy cavalry three times and caused great carnage. Our gunners charged as hussars, and took back their cannons, which had been taken from them during the fog. […]

On the 30th, the siege of Charleroi was retaken with more determination than ever. The engineer officer Marescot did himself much honor by the activity with which he carried out the work. Artillery burned the city to ashes. […]

Jourdan must send you the honorable articles by which you will see that the pride of the house of Austria has come under the yoke. The prisoner garrison is three thousand men. We found fifty pieces of cannon. The place is in powder and is nothing more than a post. [...] (pp. 440-441)

As Saint-Just lauded figures he allegedly attacked, such as Marescot, and "defeated" generals such as Lefebvre, I am not particularly inclined to believe that Saint-Just was utterly ruthless. Still, a more balanced assessment of Saint-Just and Jourdan's relationship is in order. Let me close this post by quoting Fischer, who has studied this matter more in-depth:

Jourdan claimed in his memoirs that he once again felt as if he were fighting with a guillotine suspended over his head; one failure would cause the blade to fall. Undoubtedly he felt interfered with; he wrote no letters to the Committee after Fleurus praising St. Just's aid as he had after Wattignies praising Carnot's. St. Just's feelings towards Jourdan are more difficult to penetrate. At no point did he actually complain about Jourdan's generalship, indicating that perhaps their disagreements had not disturbed him as much as they had disturbed Jourdan. [...] Furthermore, St. Just was on excellent terms with Rene Gillet. It is unlikely that he would have been so friendly with such a close colleague of Jourdan if he had Jourdan marked for death. Even so it is hard to predict what would have occurred had he been defeated. St. Just might not have shown compassion for a general who had disagreed with him repeatedly, and who had compounded his sin by losing a battle. (pp. 218-219)

I hope that this series has been enjoyable to all who read it. A huge thank you to everyone who has read and supported this series, and as usual, feel free to add comments or additional information!

#jean-de-dieu soult#jean-baptiste jourdan#louis antoine de saint-just#memoirs#letters#frev#revolutationary army

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

NEUVAINE A SAINTE JEANNE D'ARC

NOVENA TO SAINT JOAN OF ARC

My English translations are not the best I am sorry.

╰┈➤ Premier jour (first day)

Jeanne, le Seigneur a chargé l’Archange saint Michel de t’apparaître et de t’annoncer ta mission de sauver le royaume de France.

Jeanne, the Lord has instructed the Archangel Saint Michael to appear to you and announce your mission to save the kingdom of France.

Jeanne, ton grand désir de servir Dieu et de tout faire pour lui plaire,

Te font prononcer le « fiat » malgré tes craintes de ne pas être digne et capable d’accomplir cette mission.

Jeanne, your great desire to serve God and to do everything to please him,

makes you pronounce the “fiat” despite your fears of not being worthy and capable of accomplishing this mission.

Le ciel t’a donné une épée pour combattre, et les voix de sainte Catherine et de Sainte Marguerite pour te guider.

Heaven has given you a sword to fight, and the voices of Saint Catherine and Saint Margaret to guide you.

Intercède pour que nous puissions toujours répondre à notre vocation.

Intercede so that we may always respond to our vocation.

╰┈➤ Deuxième jour (second day)

Jeanne, tu rends visite au Dauphin de France

Jeanne, you visit the Dauphin of France.

Tu lui révèles qu’il est le véritable héritier de France, et fils de roi,

Qu’il sera couronné à Reims et que tu es venue pour l’aider à accomplir ce désir du Ciel.

You reveal to him that he is the true heir of France, and son of a king,

that he will be crowned in Reims and that you have come to help him fulfill this desire of Heaven.

Tu livres ensuite de nombreuses batailles contre les Anglais, et tu en sors toujours victorieuse.

You then fought many battles against the English, and you always emerged victorious.

Tu livres également bataille au péché dans ton propre camp et tu demandes à tes soldats de retrouver l’état de grâce.

You also give battle to sin in your own camp and you ask your soldiers to regain the state of grace.

Intercède maintenant pour que notre pays se souvienne de son baptême

Et retrouve le chemin des sacrements.

Intercede now so that our country remembers its baptism

And finds the way to the sacraments.

╰┈➤ Troisième jour (third day)

La semaine de Pâques de cette année 1430, alors que tu te trouves dans un fossé de Melun, les voix de saintes Catherine et Marguerite t’annoncent que tu seras faite prisonnière avant la fête de la saint Jean et que Dieu te viendra en aide durant cette épreuve.

Easter week of this year 1430, while you are in a ditch in Melun, the voices of Saints Catherine and Marguerite announce to you that you will be taken prisoner before the feast of Saint John and that God will come to you help during this test.

Tu es alors envahie d’angoisse et tentée de ne pas te soumettre à la volonté divine afin de sauver ta vie.

You are then overwhelmed with anguish and tempted not to submit to the divine will in order to save your life.

Prie pour nous, afin que nous fassions toujours la volonté de Dieu, et non la nôtre.

Pray for us, that we always do God's will, not our own.

╰┈➤ Quatrième jour (fourth day)

C’est le 26 Mai, après une rude bataille, que tu es prise par un archer du camp adverse.

It is on May 26, after a hard battle, that you are taken by an archer from the opposing camp.

Tu es ainsi arrêtée et accusée par l’Inquisition d’hérésie et d’idolâtrie.

You are thus arrested and accused by the Inquisition of heresy and idolatry.

Malgré tes craintes et tes peurs, tu te laisses emprisonner.

Despite your fears and fears, you allow yourself to be imprisoned.

Tu gardes confiance en tes voix, et tu demandes leur intercession afin de répondre aux questions qui te sont posées.

You keep trust in your voices, and you ask for their intercession in order to answer the questions that are put to you.

Demande à Dieu, pour nous, le courage et l’audace d’affirmer notre foi.

Ask God, for us, the courage and audacity to affirm our faith.

╰┈➤ Cinquième jour (fifth day)

Tu es torturée moralement, assaillie par de nombreux et interminables interrogatoires, abandonnée et trahie de tous, y compris du Roi, traitée comme une prisonnière de guerre, menacée corporellement par les gardiens de ta cellule, accusée de nombreuses fautes que tu n’as pas commises, sans avocat.

You are morally tortured, beset by numerous and interminable interrogations, abandoned and betrayed by everyone, including the King, treated like a prisoner of war, bodily threatened by the guards of your cell, accused of numerous faults that you do not have not committed, without a lawyer.

Toujours docile aux conseils de tes voix, tu réponds sans crainte à tout ce que l’on te demande.

Always docile to the advice of your voices, you respond without fear to everything that is asked of you.

Intercède pour que nous ayons toujours recours à la prière dans nos difficultés.

Intercede that we always have recourse to prayer in our difficulties.

╰┈➤ Sixième jour (sixth day)

Tous tes accusateurs s’acharnent pour te faire faillir, pour te faire contredire les faits que tu relates;

All your accusers work hard to make you fail, to make you contradict the facts you relate;

ils t’accusent, te menacent de tortures physiques, te harcèlent sans cesse durant des heures;

they accuse you, threaten you with physical torture, harass you constantly for hours;

en vain, tu as toujours réponse à toutes les questions, jusqu’au jour, où, n’en pouvant plus, effrayée par la mort, tu renies tout.

in vain, you always have the answer to all the questions, until the day when, unable to take it any longer, frightened by death, you deny everything.

Puis, par la grâce de Dieu, tu acceptes avec courage le martyre et reviens sur tes reniements.

Then, by the grace of God, you courageously accept martyrdom and reconsider your denials.

Malgré la reconnaissance de certains de tes juges de l’intervention divine dans ta conduite, tu es condamnée à mort par le supplice du feu.

Despite the recognition of some of your judges of divine intervention in your conduct, you are condemned to death by torture by fire.

Prie pour que la France relève la face et se souvienne de ses promesses faites à Dieu.

Pray for France to raise its face and remember its promises made to God.

╰┈➤ Septième jour (seventh day)

Jeanne, tu es surnaturellement soutenue par le Ciel, mais tu n’échappes pas aux angoisses provoquées par la sentence.

Jeanne, you are supernaturally supported by Heaven, but you cannot escape the anguish caused by the sentence.

Tu aurais préféré « être décapitée sept fois plutôt que brûlée et réduite en cendres. »

You would have rather "be beheaded seven times than burnt and reduced to ashes."

Sur le bûcher, une fois liée, tu demandes pardon aux anglais et à tous tes ennemis, pour les batailles livrées contre eux, et, d’une voix haute et claire, tu pardonnes à tous ceux qui t’ont condamnée.

At the stake, once bound, you ask pardon of the English and of all your enemies, for the battles waged against them, and, in a loud and clear voice, you forgive all those who have condemned you .

« Mes saintes ne m’ont pas trompée, ma mission était de Dieu. Saint Michel, sainte Marguerite et sainte Catherine, vous tous, mes frères et sœurs du Paradis, venez à mon aide… »

“My saints did not deceive me, my mission was from God. Saint Michael, Saint Margaret and Saint Catherine, all of you, my brothers and sisters in Paradise, come to my aid…”

Au milieu des flammes, tu regardes la croix qui t’est présentée, et tu prononces le Nom de Jésus avant de mourir.

In the midst of the flames, you look at the cross presented to you, and you pronounce the Name of Jesus before dying.

Sois notre modèle dans l’obéissance, dans la confiance en Dieu, et la persévérance dans notre mission

Be our model in obedience, in trust in God, and perseverance in our mission

╰┈➤ Huitième jour (eighth day)

Alors que le bourreau éteint le brasier afin que tous voient le cadavre défiguré de celle qui les a fait trembler, il écarte les cendres et le miracle apparaît devant leurs yeux effrayés :

As the executioner puts out the fire so that everyone can see the disfigured corpse of the one who made them tremble, he pushes aside the ashes and the miracle appears before their frightened eyes:

Ton cœur est là, rempli d’un sang vermeil et semblant vivre encore !

Your heart is there, filled with vermilion blood

and seeming live again!

Du soufre et de h’huile sont alors répandus dessus, le feu reprend puis s’éteint à nouveau, le laissant toujours intact.

Sulfur and oil are then sprinkled on it, the fire resumes and then goes out again, leaving it still intact.

Inquiet de ce miracle et craignant l’émotion du peuple, le cardinal d’Angleterre ordonne que tes os, tes cendres et surtout ton cœur soient jetés immédiatement dans la Seine.

Worried about this miracle and fearing the emotion of the people, the cardinal of England orders that your bones, your ashes and especially your heart be thrown immediately into the Seine.

Le bourreau dit alors : « J’ai grand peur d’être damné pour avoir brûlé une sainte »

The executioner then said: "I am very afraid of being damned for having burned a saint".

Des cris s’élèvent dans la foule : « Nous sommes tous perdus car une sainte a été brûlée ! »

Cries rise in the crowd: “We are all lost because a saint has been burned! »

Aide-nous à servir Dieu et à ne chercher que la gloire du Ciel.

Help us to serve God and seek only the glory of Heaven.

╰┈➤ Neuvième Jour (ninth day)

Après ta mort, mourut la prospérité des anglais en France. Depuis le bûcher de Rouen, ils ne connurent que déceptions et défaites.

After your death, the prosperity of the English in France died. From the stake in Rouen, they knew only disappointments and defeats.

A leur grande honte et confusion, ils furent rejetés de tous les pays qu’ils avaient conquis.

To their great shame and confusion, they were thrown out of all the countries they had conquered.

Tous ceux qui avaient jugé avec mauvaise foi la Pucelle trouvèrent la mort peu de temps après la sienne.

All those who had judged the Maid in bad faith died shortly after hers.

L’évêque Cauchon, enrichi par le Roi d’Angleterre, mourut subitement ; il fut excommunié par le Pape et ses os furent jetés aux bêtes féroces.

Bishop Cauchon, enriched by the King of England, died suddenly; he was excommunicated by the Pope and his bones were thrown to wild beasts.

Ainsi s’accomplit la prédiction faite à Jeanne, en sa prison, par ses voix:

Thus is fulfilled the prediction made to Jeanne, in her prison, by her voices:

« Tu auras secours. Tu seras délivrée par une grande victoire. Prends tout en gré. Ne te soucie pas de ton martyre. Tu viendras enfin au Royaume du Paradis. »