#John Ludin

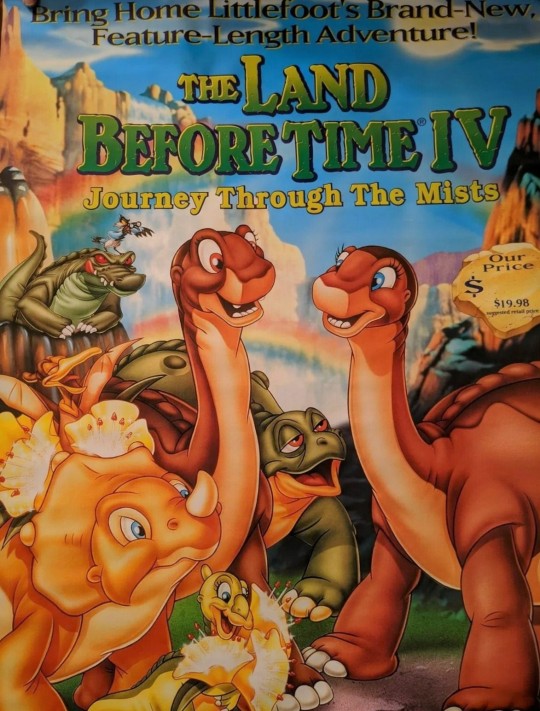

Photo

#The Land Before Time#The Land Before Time II The Great Valley Adventure#The Land Before Time III The Time of the Great Giving#The Land Before Time IV Journey Through the Mists#Roy Allen Smith#Dev Ross#Judy Freudberg#Tony Geiss#Don Bluth#Stu Krieger#John Loy#John Ludin#VHS#90s

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Official Poster And Trailer For MONTANA STORY Starring Haley Lu Richardson

Official Poster And Trailer For MONTANA STORY Starring Haley Lu Richardson

Check out these new poster and trailer for MONTANA STORY movie starring Haley Lu Richardson. Bleecker Street will release MONTANA STORY in theaters May 13, 2022

Written & Directed by Scott McGehee and David Siegel

Produced by Scott McGehee, David Siegel, Jennifer Roth

Starring Haley Lu Richardson, Owen Teague, Gilbert Owuor, Kimberly Guerrero, Asivak Koostachin, Eugene Brave Rock, Rob Story, John…

View On WordPress

#Asivak Koostachin#Eugene Brave Rock#Gilbert Owuor#Haley Lu Richardson#John Ludin#Kate Britton#Kimberly Guerrero#Montana Story#Owen Teague#Rob Story

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Afghan Jihadi Arrested for 2008 Abduction of American Journalist

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Wednesday, October 28, 2020

Afghan National Arrested for 2008 Abduction of American Journalist

The Department of Justice announced the unsealing of a federal indictment charging Haji Najibullah, a/k/a “Najibullah Naim,” a/k/a “Abu Tayeb,” a/k/a “Atiqullah” with six counts related to the 2008 kidnapping of an American journalist and two Afghan nationals. Najibullah, 44, was arrested and transferred to the United States from Ukraine to face the charges in the indictment. Najibullah will be presented today before U.S. Magistrate Judge Ona T. Wang. The case is assigned to U.S. District Judge Katherine Polk Failla.

“Najibullah is charged with taking an American journalist and others hostage in Afghanistan in November 2008. Journalists risk their lives bringing us news from conflict zones, and no matter how much time may pass, our resolve to find and hold accountable those who target and harm them and other Americans will never wane,” said Assistant Attorney General for National Security John C. Demers. “The defendant, like many others before and surely others to come, will now face justice in an American courtroom.”

Acting U.S. Attorney Audrey Strauss said: “Nearly 12 years ago, the defendant arranged to kidnap at gunpoint an American journalist and two other men, and held them hostage for more than seven months,” said Acting U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York Audrey Strauss. “The prosecution of Haji Najibullah shows that law enforcement will never stop in our mission to hold accountable those who commit violent crimes against American citizens.”

“Whether someone commits a violent act against an American citizen here at home or overseas, we’ll never stop aggressively pursuing charges against them and, when necessary, seeking their transfer to U.S. custody,” said FBI Assistant Director-in-Charge of the New York Office of the FBI William F. Sweeney Jr. “Najibullah’s reprehensible actions over a decade ago earned him a flight to the U.S. yesterday. Today he arrived in U.S. federal court to face our justice system.”

“The FBI, along with our partners, continue to work tirelessly in the pursuit of justice and to hold accountable those who are responsible for the kidnapping and hostage taking of U.S. citizens abroad,” said Assistant Director Jill Sanborn of the FBI's Counterterrorism Division. “We remain steadfast in our obligation to see justice served, regardless of the how long it may take or where those individuals are located. This investigation and resulting indictment reflects the FBI’s perseverance and commitment to the victims of these heinous acts – We never forget, and we never give up.”

“Haji Najibullah’s alleged kidnapping of a United States journalist and two Afghan nationals was a crime against America, a crime against the freedom of the press, and against the integral work of shining a light on important international affairs,” said Police Commissioner Shea. “While today’s federal indictment reflects events that occurred a dozen years ago, it shows once again that the FBI-NYPD Joint Terrorism Task Force and all of our law enforcement partners will wait as long and go as far as it takes to bring justice.”

According to the Indictment:[1]

On or about Nov. 10, 2008, Najibullah and his co-conspirators, armed with machineguns, kidnapped an American journalist (Victim-1) and two Afghan nationals who were assisting Victim-1 (Victim-2 and Victim-3) at gunpoint in Afghanistan. Approximately five days later, on or about Nov. 15, 2008, Najibullah and his co-conspirators forced the three hostages to hike across the border from Afghanistan to Pakistan, where Najibullah and his co-conspirators detained the hostages. For the next seven months, Najibullah and his co-conspirators held the hostages captive in Pakistan.

During their captivity, Najibullah and his co-conspirators forced the victims to make numerous calls and videos seeking help. For example, on or about Nov. 19, 2008, while in Pakistan, Najibullah and a co-conspirator (CC-1) directed Victim-1 to call his wife in New York. In addition, Najibullah and his co-conspirators made the victims create at least three videos in which they begged for help while surrounded by masked guards armed with machineguns. In one of the videos, Victim-1 — the American journalist — was forced to beg for his life while a guard pointed a machinegun at Victim-1’s face.

Najibullah, 44, of Afghanistan is charged with hostage taking, conspiracy to commit hostage taking, kidnapping, conspiracy to commit kidnapping, and two counts of using and possessing a machinegun in furtherance of crimes of violence. Each of the six counts of the indictment carry a maximum sentence of life in prison. The maximum potential sentences in this case are prescribed by Congress and are provided here for informational purposes only, as any sentencing of the defendants will be determined by a judge.

Ms. Strauss and Mr. Demers praised the outstanding efforts of the FBI’s New York Joint Terrorism Task Force. They also thanked the New York and New Jersey Port Authority Police, the Counterterrorism Section of the Department of Justice’s National Security Division, the Legal Attaché Office/U.S. Embassy Kyiv and the FBI's Counterterrorism Division for its assistance with this investigation, as well as the Ukrainian authorities and the Office of International Affairs of the Justice Department’s Criminal Division for their assistance in the extradition.

This prosecution is being handled by the Terrorism and International Narcotics Unit. Assistant U.S. Attorneys Sam Adelsberg, Sidhardha Kamaraju, and Michael Kim Krouse are in charge of the prosecution, with assistance from Trial Attorney Jennifer Burke of the Counterterrorism Section.

The charges contained in the indictment are merely accusations, and the defendant is presumed innocent unless and until proven guilty.

[1] As the introductory phrase signifies, the entirety of the text of the Indictment and the description of the Indictment set forth below constitute only allegations, and every fact described should be treated as an allegation.

Attachment(s):

Download u.s._v._haji_najibullah_et_al._indictment_pdf

---------------------------------------------

More:

The kidnapping victims were not identified by authorities, but the description matched the kidnapping of the journalist, David Rohde, who worked for the Times, and an Afghan journalist, Tahir Ludin, as they were heading to interview a Taliban leader.

Both made a dramatic escape from a Taliban-controlled compound in Pakistan’s tribal areas more than seven months after their Nov. 10, 2008, kidnapping. Their driver, Asadullah Mangal, was the third kidnapping victim and escaped a few weeks after Ludin and Rohde.

0 notes

Text

Notes from ‘New Media Art’, Mike Tribe and Reena Jana (2006)

Notes

- the conceptual and aesthetic roots of new media art extend back to the Dada movement.

- In new media art, appropriation has become so common that it is almost taken for granted. Appropriation of online media within art is reminiscent of Dadaist collages, DuChamp’s readymades and Bruce Conor’s found footage films.

- New media art can be seen as a response to the information technology revolution and the digitisation of cultural forms. As such, many new media art forms are linked to popular and commercial culture.

- The new media art movements hit their stride in the late 1990s, as the first generation of artists who grew up with the internet, personal computers and video games came of age. These new artists were comfortable with new technology, furthering the development of art and technology into the 21st Century

- The term Net Art (from net.art) originated from eastern Europe in the mid 1990s, no coincidence in terms of historical happenings. At this time, the Soviet Union was collapsing, lending artists in the region a unique perspective on the internet’s dot-com era transformation - they were living in societies making the transition from socialism to capitalism, mirroring the privatisation of the internet (a phenomenon that continues to occur today).

Examples of new media art to explore:

(all of the underlined text is a link to the work)

jodi.org, Joan Heemskerk and Dirk Paesmans

Brandon, Shu Lea Cheang (Guggenheim link)

Genetic Response 3.0, Diane Ludin

WWWArt Award, Alexi Shulgin

Prepared Playstation, RSG

Floodnet, Electronic Disturbance Theatre

Borderhack, Fran Illich

Free Radio Linux, r a d i o q u a l i a

Trigger Happy, Thomson and Craighead

(pixel artist collective) eBoy

Every Icon, John F. Simon, Jr

Shredder 1.0, Mark Napier (info)

The Intruder, Natalie Bookchin (video)

Velvet-Strike, Anne-Marie Schliener, Brody Condon and Joan Leandre

Carnivore, RSG

UMBRELLA.net, Katherine Moriwaki

Dialtones: A Tele Symphony, Golan Levin et al

My Boyfriend Came Back From the War, Olia Lialina

After Sherrie Levine, Michael Mandiberg

OPUS, Raqs Media Collective

Life Sharing, 0100101110101101.ORG

BUST DOWN THE DOOR AGAIN! GATES OF HELL-VICTORIA VERSION, YOUNG-HAE CHANG HEAVY INDUSTRIES

----------------------------------------

New Media Artist Collectives:

®™ark, Bureau of Inverse Technology, Fakeshop, Institute for Applied Autonomy, Mongrel, VNS Matrix

0 notes

Text

John Ludin

John Ludin

John Ludin #HD #Wallpapers and Background #Images. Download for free on all your devices – #Computer, Smartphone, or Tablet.

View On WordPress

#John Ludin Awards and nominations#John Ludin Career#John Ludin Early life#John Ludin Film career#John Ludin Filmography#John Ludin Images#John Ludin Movie#John Ludin Net Worth#John Ludin Personal life#John Ludin Photo#John Ludin Picture#John Ludin Wallpaper

0 notes

Audio

Robag Wruhme guest mix for Claude VonStroke The Birdhouse Radio Show by Cohenshi, https://ift.tt/2OmfQnS Dirtybird Campout artist guest mix feature. @robag_fm Info & Booking: Latin America: Cohenshi | [email protected] North America: Paradigm Talent Agency | [email protected] Europe & rest of the world: Kompakt | [email protected] • • • TRACK LIST: INTRO MARTIN KOHLSTEDT - SENIMB LUKE SLATER - LOVE - BURIAL REMIX ROBAG WRUHME - TOPINAMBUR IVAYLO - SYKLON ROBAG WRUHME - WUZZELBUD FF TRUNCATE - UTILITY_2 MAX COOPER - VOLITION - ROBAG WRUHME ́S BOTNAX CAAL RMX BOOKA SHADE - MANDARINE GIRL - HEARTTHROB KONRAD TROY RMX MIKE DEHNERT - DETROIT SWITCH BACK TO CITY EDIT 2 EXTRAWELT - PINK PANZER TRUNCATE - OUR BODIES NORMAN NODGE - NN 74 ARCHITECTURAL - A GIRL WITH NO FRIENDS LUKE SLATER - LOVE - MARCEL DETTMANN ́S BLACK GLOVES RMX DONATO DOZZY - TB MAETRIK - WORK ME REINHARD VOIGT - DER MANN DER NIE NACH DEUTZ KAM JOHN TEJADA + ARIAN LEVISTE - IT ́S THE BEAT ECTOMORPH - PARALLAX ANDRE KRONERT - LAKE TAHOE SYSTEM 7 - SPACE BIRD - DUBFIRE RMX PAVEL LUDIN - AUTOMOTIVE# ÂME - NO WAR - RY X REMIX OUTRO

0 notes

Text

‘Damascus Cover’: Film Review

3:11 PM PDT 7/4/2018 by Stephen Dalton Jonathan Rhys Meyers performs an undercover Mossad agent on a lethal mission to Syria in Daniel Zelik Berk’s interval spy thriller. Touted as a possible future James Bond on numerous events during the last decade, Jonathan Rhys Meyers seems to have made his audition reel in Damascus Cowl, a lumbering old-school spy thriller by Israeli writer-director Daniel Zelik Berk. Based mostly on a 1977 novel by Howard Kaplan, however with a plot up to date to the tip of the Chilly Struggle, Berk’s debut cinematic function is overstuffed with groaningly acquainted espionage tropes. Even with its modestly starry forged, together with a last display credit score for the late John Harm, audiences are unlikely to be both shaken or stirred when Vertical Leisure open the movie in theaters on July 20. Rhys Meyers stars as Ari Ben-Zion, an undercover Israeli spy dwelling below a pretend German identification in late 1980s Berlin. Simply because the Berlin Wall falls, he botches his mission to carry again a treacherous double agent alive. Recalled to Tel Aviv below a darkish cloud, Ari’s skilled competence and psychological welfare come into query. Desirous to show himself to his wily Mossad boss Miki (John Harm), Ari volunteers for a harmful job behind enemy traces, with the intention of smuggling a chemical substances weapons scientist and his household out of Syria. Arriving in Damascus, he poses as a German carpet importer with neo-Nazi sympathies, which brings him into contact with suave former Nazi Franz Ludin (Jurgen Prochnow). He additionally encounters flirtatious American photojournalist Kim (Olivia Thirlby), who appears immediately eager on dragging Ari into her darkish room and seeing what develops. Betraying its 1970s supply materials with each creaky line and clunky plot twist, Damascus Cowl is a pedestrian effort throughout the board. Berk seems to be taking type and temper cues from the Jason Bourne movies, which had been equally conservative prospects at coronary heart, however he plainly lacks the directing panache and beneficiant funds required to glam up this dowdy outdated potboiler into an attractive fashionable spy thriller. The motion scenes are threadbare, counting on stagey hand-to-hand fight and scrappy gunfights, whereas the stilted romance between Ari and Kim feels wholly implausible and low on sizzle. The Nazi subplot, central to Kaplan’s e-book, additionally melts away into insignificance right here. In its favor, Damascus Cowl is handsomely shot in summery colours by cinematographer Chloe Thomson, who makes resourceful use of aerial drone footage of Berlin, Tel Aviv and Casablanca, which stands in for Damascus. Harm strikes a reliably elegiac be aware in a whiskery supporting position which, as with most of his autumnal work, elevates mediocre materials by just a few notches. And Rhys Meyers appears to be like male-model attractive in a sequence of sharp fitted fits, though his cold, stiff efficiency largely consists of pulling variations on Derek Zoolander’s signature Blue Metal look. Thirlby is the one actual firecracker right here, bringing a compellingly nervy ambiguity to a personality whose divided loyalties are thuddingly foreshadowed proper from her first scene. Damascus Cowl ends on a evenly cynical twist meant to critique the morally doubtful backstage deal-making behind superpower spy video games. Sadly, Berk’s stale screenplay merely lacks the heft or depth to carry it above third-hand homage to earlier, higher, smarter movies. On the energy of this flimsy star automobile, Rhys Meyers is not going to be sipping dry martinis in a tuxedo any time quickly. Manufacturing corporations: Xeitgeist Leisure Group, Marcys Holdings, BBMForged: Jonathan Rhys Meyers, Olivia Thirlby, John Harm, Jurgen Prochnow, Igal Naor, Navid NegahbanDirector: Daniel Zelik BerkScreenwriters: Daniel Zelik Berk, Samantha NewtonProducers: Huw Penallt Jones. Hannah Chief, Jonathan Rhys Meyers, Joe ThomasCinematographer: Chloe ThomsonEditor: Martin BrinklerMusic: Harry Escott93 minutes http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/thr/reviews/film/~3/7UaTq_wzb3M/damascus-cover-review-1125011

https://www.news9ontime.com/damascus-cover-film-review/

0 notes

Photo

HomeSKIP TO CONTENTSKIP TO NAVIGATIONVIEW MOBILE VERSION The New York Times Share

Cover PhotoFrom left: William Tyler, Monica Valentine, George Wilson, the creative director Tom di Maria, John Martin and Dan Miller. Credit Jeff Minton for The New York Times A Training Ground for Untrained Artists An Oakland nonprofit has a startling track record for helping developmentally disabled adults become prolific — and profitable — artists.

By NATHANIEL RICHDEC. 16, 2015 The artists arrived at the Creative Growth Art Center shortly after 9 a.m. Most come on East Bay Paratransit buses, which bring them from Alameda, Castro Valley and San Francisco, but a few travel independently. William Tyler takes the orange line BART from his group home in Union City. In 37 years, he has almost never been late. Terri Bowden takes the BART from Fremont, accompanied by a life-size matboard Fred Flintstone. It is a familiar sight to commuters in Oakland’s 19th Street BART station: the legally blind woman with a mohawk and her inanimate sidekick. Bowden periodically replaces the doll’s face; before Fred Flintstone, it was Abraham Lincoln, Michael Jackson, Robert Plant and, at some point, nearly every Creative Growth staff member. John Martin, who lives with his aunt 20 blocks away, walks to work, but not in a straight line. He stops at coffee shops, which fill his empty Gatorade bottles with coffee; at churches, which hand him donated cans of food; and at trash bins, where he rummages for plastic toys, sunglasses and flip phones.

The artists gathered at long tables in the cafeteria. They hung their jackets and stored their lunches in the communal refrigerator. There was a lot of waving and hugging. ‘‘I miss Classie,’’ one of the artists said. It is a common sentiment, even four months after the death of Classie Rozier, the staff nurse for 30 years. On the wall above the tables hang two portraits of her: a framed painting by John Martin and a collage, made by several artists, with three photographs of Classie’s head glued over a red heart.

Dan Miller placed a blue hockey helmet on his head. Tyler sat alone with his head resting in his palm, half-smiling. ‘‘I don’t have any money,’’ Martin mumbled. ‘‘Nah. I don’t have any money.’’

A Creative Growth staff member overheard him. ‘‘You have a lot of money, John,’’ she said.

‘‘I don’t know nothing about that,’’ Martin answered.

‘‘Trust me,’’ she said, laughing. ‘‘You have a lot of money.’’

In June, Facebook bought 35 of Martin’s tool sculptures — cutouts of scissors, hammers and switchblades — for $8,000 and installed them in its enormous new Menlo Park headquarters. Facebook has recently commissioned Martin for 20 more. Martin was invited to the opening but declined to go. He usually doesn’t attend his own exhibitions; at one recent show, Martin ignored the work on the wall and examined the contents of a toolbox that had been left behind by the gallery staff.

Continue reading the main story RELATED COVERAGE

SIGN OF THE TIMES Outside In JUNE 1, 2015

ART REVIEW ‘Art Brut in America’ Highlights Outsider Artists, No Longer Looking In OCT. 22, 2015 Advertisement

Continue reading the main story Facebook’s acquisition is the latest but not nearly the most impressive of a recent series of market successes for Creative Growth, which was founded in Berkeley in 1974 and has since relocated to a former auto-repair shop in downtown Oakland. Creative Growth has capitalized on the surging interest for work by self-trained artists or, as The Wall Street Journal has put it, ‘‘artists who don’t know they’re artists’’: work that in less sensitive times has been referred to as outsider art, naïve art, Art Brut and art of the mentally ill. Such art has experienced a boom during the past 15 years. The work of the field’s most prominent figures — Henry Darger, William Edmondson, Martín Ramírez and Augustin Lesage — has sold in the mid- and high six figures by Christie’s and other auction houses in New York and Paris. The Guggenheim, the Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art have acquired work by these artists for their permanent collections.

A majority of the most famous self-taught artists are dead. In many cases, their work was not discovered until after their deaths. It has become difficult to find their art for sale, and what exists is expensive. Collectors and galleries, eager to satisfy the market’s demand, find themselves in an odd position. Typically dealers in search of new art stars comb M.F.A. programs and the studios of established masters. But where might they discover ‘‘artists who don’t know they’re artists’’? Increasingly, these dealers are swarming to this converted auto-repair shop in downtown Oakland.

Creative Growth was born in the garage of Florence Ludins-Katz, an artist and educator, and her husband, Elias Katz, a psychologist who had worked for years at the Sonoma State Home. The Katzes were alarmed by the mass closure of psychiatric hospitals in California, where half of all patients had been deinstitutionalized during the 1950s and 1960s. Shortly after Ronald Reagan assumed the governorship in 1967, he signed the Lanterman-Petris-Short Act, which blocked involuntary hospitalization and resulted in most of the remaining patients being turned out. Few accommodations were made for them after release, leading to an exponential rise among the mentally ill in homelessness and imprisonment.

The Katzes decided to create a center for former state-hospital patients with developmental disabilities, primarily Down syndrome and autism. Their goals, as stated in their 1990 book, ‘‘Establishing the Creative Art Center for People With Disabilities,’’ included not only therapeutic support and vocational training but also ‘‘creation of work of the highest artistic merit.’’ They wrote: ‘‘Even though a human being may be handicapped or disabled, this does not change his need to fulfill himself to the greatest of his capacity.’’

This was not an altogether iconoclastic notion; arts and crafts were offered in many state facilities. What was novel at the time, though, was the Katzes’ insistence that Creative Growth sell artwork to the public. ‘‘The students gain by feeling their art is worthy of being bought and perhaps reproduced,’’ they wrote. ‘‘The Art Center takes pride in the recognition that the art of persons with disabilities is much sought after and has value to society.’’

In 1978, after moving the studio to a storefront in Oakland and receiving a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Katzes opened an adjacent gallery, the first in America dedicated to art by people with disabilities. In 1982, Creative Growth expanded further to a 12,000-square-foot, two-story brick automobile-repair shop on 24th Street. The main open space is occupied by long worktables visible from the sidewalk through a row of large plate-glass windows. There are discrete work areas for drawing and painting, woodworking, printmaking, ceramics, rug making, textiles and mosaics. Teachers assist but are under orders never to guide or instruct, unless asked to do so by an artist. Next door, connected to the studio, is the gallery, which holds seven exhibitions a year. For decades these openings were mainly attended by families and friends of the clients, and occasionally local professional artists, who might buy a painting or sculpture for a nominal price. They had the quality of a local flea market or open mike.

This began to change in the late 1980s, when the work of Dwight Mackintosh, who came to Creative Growth after spending 56 years in mental institutions, was noticed by John MacGregor, a Bay Area art historian. MacGregor was a popularizer of Art Brut, the term coined by the artist Jean Dubuffet to describe work created in solitude by untrained artists. At the time, Dubuffet’s Collection of Art Brut in Lausanne, Switzerland, founded in 1976, was the world’s only such museum; after learning of Mackintosh’s work from MacGregor, the museum gave the artist a one-man show. The few American gallerists who collected outsider art, like Phyllis Kind in New York and Judy Saslow in Chicago, began to buy Mackintosh’s drawings. A Warner Brothers executive noticed his work in Michael Stipe’s personal collection and commissioned the artist to illustrate a Lollapalooza concert poster. The sudden critical and economic success caught Creative Growth’s board by surprise. They knew how to sell work to members of the local community but were unprepared for Manhattan gallerists, rock stars and international dealers.

Photo

John Martin. Credit Jeff Minton for The New York Times Collectors began to visit the studio regularly, and work by other Creative Growth clients started to appear in group shows devoted to artists with disabilities. But it was not until 1999, when art critics began to praise the unusual, intricate sculptures of Judith Scott, a deaf and mute artist with Down syndrome, that Creative Growth’s board decided to change its mission. There was major interest in Scott’s work; there might also, it seemed, be a major market for it. If the professional art world was going to come to Creative Growth, the center needed to handle itself more professionally. It needed someone who understood the art market. It needed someone who knew how to sell.

Tom di Maria, who has been the director of Creative Growth since 2000, toured the studio at 9:30, greeting the artists as they entered the studio. Roughly 160 artists work at Creative Growth, but not everybody attends each day. Some, like William Tyler, have come every day for decades; others visit infrequently. Most are introduced to Creative Growth by the Regional Center of the East Bay, a nonprofit organization contracted by the state to provide services to people with developmental disabilities. Applicants do not need to express any artistic ability, inclination or even interest.

Di Maria often invites visitors to the gallery, and on this day he hosted an art collector and his wife, an interior designer, visiting from Santa Monica. The designer introduced herself to an artist named Monica Valentine. When the designer went to shake Valentine’s hand, she realized that Valentine was blind. Her eyes are prosthetics.

‘‘Can you see a little bit?’’ the interior designer asked.

‘‘I’m totally blind.’’

Valentine was dressed entirely in green: mint sneakers, lime socks, olive shirt, dusky green puffy jacket, emerald glass stud earrings, neon plastic sunglasses and a headband made out of interweaved strands of harlequin and laurel fabric. Around her neck hung, from chartreuse nylon, a green bicycle reflector.

Valentine covers foam packing forms with sequins and beads, held in place by sewing pins. The current piece was shaped like a cinder block. She called it ‘‘A Piece of Cake.’’ She hoped to be finished in time for her 60th birthday later that week. Before Valentine on the table were three plastic boxes, each with a half-dozen compartments. One box contained sequins, another beads, the third pins. With the dexterity of a veteran crocheter, she selected a pin, stuck it through a bead and a sequin and punched it into the foam. When a work is completed, the whiteness of the foam is almost entirely obscured beneath bright fields of color. Creative Growth’s gallery guide describes Valentine’s densely sparkling creations as ‘‘crown jewels of a lost disco civilization.’’

‘‘How can you tell the difference between colors?’’ the interior designer asked.

‘‘I feel them,’’ Valentine said.

‘‘Like ... they have different temperatures?’’

‘‘Blue is cold,’’ Valentine said. ‘‘Yellow is warm. Green is cool.’’

‘‘It’s so incredible that you can feel that. Because people who have eyesight can’t — ’’

‘‘Do you ride bicycles where you live?’’ Valentine asked.

The designer paused. ‘‘Where I live it’s really hilly, so I don’t,’’ she said. ‘‘I’m not strong enough.’’

Valentine showed the visitor her reflector necklace. ‘‘Do you like the reflector? What does it remind you of? Grass?’’

After the couple from Santa Monica left, Valentine called over one of the staff members, Kathleen Henderson.

‘‘What things are green, Kathleen? Can balloons be green?’’

‘‘Sure they can.’’

‘‘Can cars be green?’’

‘‘Yes, Monica. Cars can be green.’’

‘‘Kathleen?’’

‘‘Yes, Monica?’’

‘‘What things are red?’’

Photo

Dan Miller. Credit Jeff Minton for The New York Times ‘‘When the opportunity exists,’’ the Katzes wrote, ‘‘we have seen the creative impulse burst forth like a surge of floodwater when the dam has been removed. We have seen people cry when viewing their own work. We have seen the joy in their faces. ... We have seen, and we believe.’’

There is no better example of a dam being removed and a creative impulse bursting forth than the case of Judith Scott, who was brought to Creative Growth in 1987 by her fraternal twin sister, Joyce. The sisters were born outside of Cincinnati in 1943 and were reunited in California after 40 years apart. Judith never learned to speak, having lost her hearing in infancy from scarlet fever. Her deafness went undiagnosed for decades, so she never learned to speak or sign. Her muteness was attributed to low I.Q. Doctors advised the Scotts to institutionalize Judith and cease all contact. When the sisters were 7, their parents took Judith in the middle of the night from the bed she shared with Joyce and left her at the Columbus State Institution. Joyce, violating her mother’s wishes, visited the institution as an adult and found her sister distraught, living in near total isolation. When Judith showed an interest in creating art, her crayons were confiscated. According to Joyce, Judith was declared ‘‘too retarded to draw.’’

During her first two years at Creative Growth, Judith Scott appeared unengaged, occasionally making drawings but more often sitting blankly, or napping, at her worktable. It was not until she was placed in a textile course taught by the artist Sylvia Seventy that she began to wrap. She roamed through the center’s storeroom, gathering objects — a broom, a broken chair, a tissue box, bamboo slats — that she wrapped in twine, thread and yarn. The first sculpture she completed looked like two small human figures tied together. ‘‘I understood,’’ Joyce writes, in a forthcoming book about her sister, ‘‘that she, too, knew us as twins, together; two bodies joined as one. I wept.’’

Scott’s sculptures grew more elaborate with time. They attracted the attention of MacGregor, the art historian, who made her the subject of a 1999 monograph, ‘‘Metamorphosis.’’ The next year Creative Growth decided to hire di Maria as its new executive director. His chief duty would be to promote Scott’s work. Board members told di Maria that they thought her work might be important but didn’t know what to do with it.

They also explained that they now wanted their clients to be thought of not as artists with disabilities but as ‘‘contemporary artists.’’ Di Maria, who previously worked as assistant director of the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, didn’t have to be convinced. He was immediately taken by the merit of the work being produced at Creative Growth, he said. The center, he felt, also offered an escape from the pretensions of the art world. ‘‘It was pure,’’ he says. ‘‘I don’t mean to fetishize that word, but it’s true. They are using their work as a means to communicate.’’

Shortly after di Maria was hired, he received a visit from Lucienne Peiry, the director of Lausanne’s Collection of Art Brut, which had given Dwight Mackintosh his first major show. Peiry wanted to determine whether Scott fit Dubuffet’s definition of an outsider artist. After observing her closely for several days, Peiry concluded that, though Scott worked in a studio with other artists, she did not respond to them — preserving the sense of isolation and imperviousness to influence that was crucial to Dubuffet. Peiry made Scott the subject of a 2001 show, which later traveled to New York, Hong Kong and Tokyo.

With Joyce Scott’s blessing, di Maria increased the price of her sculptures from $200 apiece to $5,000, putting it in line with sculpture by other emerging contemporary artists who had appeared in a museum show. When the pieces sold quickly, he increased the price to $15,000. (Creative Growth, like most professional galleries, splits every sale evenly with the artist.) Scott’s work was the subject of a 2002 show at the Exploratorium in San Francisco and was featured at the Outsider Art Fairs in New York and Paris. Judith Scott’s heart gave out in 2005 while on a weekend retreat with her sister; she died in Joyce’s arms. Di Maria was never certain whether she understood that her work was being sold or even exhibited.

‘‘I was with her at two or three exhibitions of her work,’’ di Maria said. ‘‘She wasn’t so interested. If she’d see one of her sculptures, she would do this thing where she’d kind of pat it on the head, as if it were her little kid. She was interested when people came to the studio and watched her work. She would shake hands. I feel that she knew that people were paying increasing attention to her. I don’t know if she made the connection to the sculpture.’’

As William Tyler worked on a drawing, a touring group from a center for people with traumatic brain injuries paused to observe him. Tyler’s method is patient, glacial, precise. He pauses often to think, his head resting in his hand in a dreamy pose. He draws in black marker on white paper, creating ordered landscapes and portraits, many of them depicting him and his brother, Richard. The brothers worked at Creative Growth together until seven years ago, when, according to staff members, it was discovered that Richard was abusing William. They have not seen each other since, but in William’s drawings, Richard continues to appear as a smiling, beatific presence.

Tyler’s canvases are often dominated by lines of neat text, framed in black boxes, that reflect his obsessions: geography, crime news, dates and times, his fear of swimming, his love of magic. A storefront occupied the bottom left corner of his work in progress, beside a series of flags of his own invention. The rest of the canvas was taken up with text:

BAD MAN WAS SHOT A GOOD MAN AT LAKE MERRITT FOR GOLDEN STATE WARRIORS / PARADE IN DOWNTOWN IN OAKLAND, CA, ON FRIDAY, JUNE 19, 2015. / BAD MAN IN JAIL IN PRISON FOR RIGHT NOW FOR BAD PEOPLE. / POLICE OFFICER WAS TAKE A GUN FROM BAD MAN IN PAST FOR NOW.

Tyler is a dedicated watcher of television news. In the news that week was the mass murder at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, S.C., as well as a shooting during the victory parade for the Golden State Warriors’ N.B.A. championship.

‘‘You heard about the nice people in Charleston, South Carolina?’’ he asked me. ‘‘Man shot them. He’s a bad man. They put him in jail. Things happen for a reason.’’

I asked where he got his news.

‘‘Channel 11 news,’’ Tyler said. ‘‘Channel 7 news. Channel 71 news. Channel 72 news. Channel 75 news. CNN. Fox News. Weather.’’

ALL SWIMMINGS FOR BAD FUNNIES ARE AT POOLS AND BEACHES FOR RIGHT NOW. WHY! / DON’T LET HAPPEN AGAIN ABOUT SPORTS FANS AND SWIMMINGS FOR RIGHT NOW / AT ALL. / NO BUSINESS FOR BAD SPORTS FANS AND SWIMMINGS FOR RIGHT NOW AT ALL.

Tyler spoke about a trip he took with his brother to Hawaii. It was financed by money earned from his artwork. ‘‘Eight-day vacation,’’ he said. ‘‘Me and Richard went in 1988. We went to the National Memorial Cemetery. Pearl Harbor Museum. We had lunch at the pineapple field. I drank pineapple juice. At Hawaii Island we had pancakes with butter and banana syrup. We took Aloha Airlines to the Big Island, Hawaii. Ate lunch on the airplane.’’

NO NEWSPAPERS FOR RIGHT NOW WERE GOT THROW AWAY IN PAST. / DON’T FORGET A RECEIPTS FOR RIGHT NOW FOR EVERYONES. / BE HAPPIES FOR RIGHT NOW AT THIS REALITY FOR EVERYONES.

Tyler said that he was born on April 23, 1954, a Friday. He said that he grew up in Berkeley and lives in Union City. ‘‘Don’t get lost on this planet Earth,’’ he said. ‘‘Things happen for a reason.’’

Slide Show

SLIDE SHOW | 11 Photos Liberated Expression Liberated ExpressionCreditCreative Growth Art Center Writing 20 years ago in The New York Review of Books, the British critic Rosemary Dinnage described the allure of outsider art as ‘‘the fantasy that over there, on the other side of the insanity barrier, is a freedom and passion and color that were renounced in childhood.’’ Underlying 20th-century art, wrote Dinnage, was ‘‘the longing for a return to something direct and strong and primitive.’’ You can see this longing in the art of Paul Gauguin, Alberto Giacometti, Marcel Duchamp and André Breton — artists influenced by the work of indigenous tribes, children and patients of mental asylums. Max Ernst assembled a 1919 exhibition in Cologne, Germany, in which Dadaist work was set beside art by the clinically insane. The African tribal sculptures at the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro in Paris fascinated Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse and led to transformations in their style. Paul Klee declared children, mental patients and North African tribesmen his artistic idols. ‘‘Neither childish behavior nor madness are insulting words,’’ he wrote. ‘‘All this is to be taken very seriously, more seriously than art of the public galleries, when it comes to reforming today’s art.’’ When the trappings of artistic fashion have come to be seen as restrictive, artists have sought the work of those ignorant of fashion.

Jean Dubuffet’s ‘‘Art Brut’’ designation was not an embrace of self-taught art so much as a rejection of its appropriation by conventional artists. Inspired by the Heidelberg psychiatrist Hanz Prinzhorn’s 1922 book, ‘‘Artistry of the Mentally Ill,’’ Dubuffet formulated a set of criteria to distinguish artwork made by society’s outsiders from work derivative of it: A true outsider artist had to work in total isolation, impervious to influence and unmotivated by any hunger for fame, status or profit. Over time Dubuffet saw reason to expand his criteria, however, and today no definition of ‘‘outsider art’’ withstands scrutiny; the two art worlds, outsider and insider, increasingly tend to bleed into each other. Even so, the fantasy of the notion of purity persists. It does more than persist. It sells.

The recent bull market for self-taught art has coincided with di Maria’s directorship of Creative Growth. Whether di Maria saw this market change coming or helped to bring it about, he understood that Creative Growth was poised to benefit from it. But first he had to establish the integrity of all the artists under his care — not just Judith Scott. He realized, as soon as he was made director, that major things would have to change. The studio space, for instance: After 18 years, it still looked like an auto-repair shop. ‘‘If the building doesn’t seem contemporary, the artists won’t seem contemporary,’’ he informed the board of trustees, shortly after he began. He began a $1.8 million fund-raising campaign and in 2008 hired the architect Anne Fougeron to create a more contemporary design, emphasizing natural light and clean lines. The gallery, which previously resembled an overstuffed attic, with unframed artwork covering every inch of the walls, was painted white. Exhibited works were framed and hung professionally, surrounded by plenty of blank space, as in a Chelsea gallery.

Newsletter Sign UpContinue reading the main story The New York Times Magazine The best of The New York Times Magazine delivered to your inbox every week, including exclusive feature stories, photography, columns and more.

Enter your email address Sign Up

You agree to receive occasional updates and special offers for The New York Times's products and services.

SEE SAMPLE PRIVACY POLICY OPT OUT OR CONTACT US ANYTIME The center had long been staffed by local art teachers, but state budget cuts in 2010 terminated that program. Given the opportunity to hire a new staff, di Maria selected exclusively professional artists and art administrators. ‘‘From me to the bookkeeper, we all went to art school,’’ he said. ‘‘No one has a social-services background or a psychiatric background. This is an important part of our philosophy: Artists should work with artists.’’

The final step was to gain prestigious institutional support for Creative Growth’s artists. As Scott’s work grew in renown, di Maria donated sculptures to the American Folk Art Museum, the Milwaukee Art Museum and the Collection of Art Brut, forming relationships that would benefit his other artists. He organized a widely attended conference in Oakland and pursued partnerships with collectors and galleries, like Matthew Higgs’s White Columns, which regularly includes Creative Growth artists in its exhibitions. In 2008 Creative Growth even opened a gallery in Paris, Galerie Impaire, to sell work more easily to European collectors. Di Maria also continued to raise prices. ‘‘In the contemporary art world,’’ he says, ‘‘if a work is priced too low, certain collectors won’t buy it. They assume that price is a signifier of value.’’ He learned that at his first Outsider Art Fair. The pieces on sale for $50 went unsold. Those priced at $1,000 sold out.

More recently Creative Growth entered a phase that di Maria refers to as ‘‘the Hollywood stuff.’’ The center collaborated with Marc Jacobs and Paper Magazine. Cindy Sherman and David Byrne hosted fund-raisers. T-shirts designed by Creative Growth artists have been modeled by Scarlett Johansson, Drew Barrymore and the Sports Illustrated swimsuit model Michelle Vawer. The Museum of Modern Art, after acquiring work by Scott for its permanent collection, has purchased paintings by Dan Miller and William Scott, who paints idealized portraits of African-American leaders, San Francisco and women from his church. This year Judith Scott was the subject of a major exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum. Her sculptures have now sold for as much as $45,000, and di Maria has declined offers more than three times as high.

It is not advertised, but the Creative Growth studio is open to the public. Most visitors who ask permission are allowed to observe the artists, and many of the artists welcome visitors. One recent afternoon, two white-haired collectors watched John Martin as he drew a tractor with a black Sharpie. Martin is tall and solidly built, with large hands and a friendly smile. On the table beside him, a small boombox played Ice Cube’s ‘‘It Was a Good Day.’’

‘‘Do you have a tractor like this?’’ Martin asked the couple.

The woman, supporting herself on a cane, pointed at Martin and whispered his name to her husband.

‘‘You can buy this tape,’’ Martin said, gesturing to his boombox. ‘‘You can put it in your car. I can’t tell you where you can get the tape.’’

He drew a man on the tractor, wearing a backward cap. He said it was Ice Cube.

‘‘I like his music,’’ Martin said. ‘‘I saw him on the TV set. I don’t have enough money for this man’s record.’’

Martin opened a Chinese magazine written entirely in Mandarin. It contained features on technology, business and culture. The elderly couple scrutinized his every movement, as if observing a living artwork.

‘‘It’s a book on Chinese food,’’ Martin said. ‘‘Let me see what they got on sale.’’

Photo

William Tyler. Credit Jeff Minton for The New York Times He flipped the pages. There were photographs of men giving speeches.

‘‘Where’s this restaurant? This says it’s in Chinatown. Let me see how much it costs.’’ He continued flipping until he came to images of food; a restaurant review, perhaps. ‘‘Stir-fried shrimp, $10,’’ Martin said. ‘‘I think they got shrimp, red lobster, stir-fried fish. Chicken chow mein. Meatballs, pasta, rice. Tomato sauce.’’

He returned to his drawing. He drew a single letter on each of Ice Cube’s teeth, copying the letters from a subscription form that had fallen out of Flash Art magazine. The letters were ‘‘v,’’ ‘‘d,’’ ‘‘w’’ and ‘‘f.’’ I asked what the letters stood for.

‘‘Music,’’ Martin said.

Visitors to Creative Growth, whether professional artists, collectors or curious passers-by, are invariably astonished by the amount of high-quality work being produced. ‘‘The best work made here is absolutely no different from the best work made anywhere,’’ says Lawrence Rinder, the director of the Berkeley Art Museum and the Pacific Film Archive. ‘‘I was the dean of an art school for four years. If we had the same percentage of success, we’d be the best art school in all of history.’’

What accounts for this unusual rate of success? Rinder credits ‘‘the character of these studios and the methodology that somehow inspires creativity at a consistent and high level.’’ The center does offer ideal working conditions. Stephen Beal, president of the California College of the Arts and former board president of Creative Growth, also cites them: ‘‘The flexibility they have, how they support an artist’s evolving way of working, who sits where, all those small things contribute to the quality that comes out of there. Maybe you’d get similar kinds of things out of everybody if you supported them that way.’’

Would you? Would you have the same results if you offered a Creative Growth residency to the next 160 people who walked down 24th Street? Creative Growth’s clients are not preselected for artistic talent. Many have never tried to make art before. Might it be possible that the work’s originality has something to do with the fact that those creating it have led unusual lives, under unusual pressures, which have caused them to view the world in unusual ways?

The question yields uneasy responses. Rinder rejects the idea forcefully. ‘‘Both instinctively and intellectually I try to separate that out.’’ Di Maria, however, acknowledges that a connection exists. ‘‘The culture of disability informs the voice of the work,’’ he says. ‘‘I’ll be in Japan, working with artists with Down syndrome, or I’ll be in Finland, working with artists on the autistic spectrum, and I’ll see similarities in style or form to artists with similar disabilities in other cultures. So maybe that’s its own culture, too.’’

Yet Creative Growth and its supporters tend to minimize the artists’ disabilities wherever possible. When asked to describe the center’s artists, di Maria even resists ‘‘self-trained artists.’’ ‘‘Work that doesn’t relate or respond to art history,’’ he says, ‘‘that’s how I describe what our artists do.’’ Di Maria routinely turns down invitations for exhibitions that emphasize the disabilities through artist photographs or biographical statements. Nor does Creative Growth participate in exhibitions that carry the label ‘‘Outsider Art,’’ with the notable exception of the annual Outsider Art Fair in New York, the field’s most prominent showcase. An extreme example of this approach was a recent show at the Fraenkel Gallery in San Francisco, ‘‘The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter,’’ which included no wall labels whatsoever. It was only by reading an informational pamphlet, available by request, that visitors could determine that some of the artists were from Creative Growth.

The effacement of biographical information avoids the danger of aestheticizing the disability or exploiting the disability to sell the work. But it also contravenes a dominant trend in the contemporary art scene. The artist’s biography and artist’s statement have become major marketing tools. Strong narratives sell. And Creative Growth artists tend to have profound, heartbreaking stories. Nearly every review of Judith Scott’s art, whether in The New Yorker or Artforum, leads with her life story. Di Maria is therefore put in the awkward situation of trying to de-emphasize the artist’s disability while recognizing that, for many collectors and critics, the disability is central to the work’s appeal.

Dan Miller was spending the afternoon in an action-painting class, in which the artists stood in front of upright canvases. Miller’s paintings are composed of words written on top of one another, creating dizzying palimpsests that bear some resemblance to Cy Twombly’s scrawled glyphs. He wrote the word ‘‘Grainger’’ in blank acrylic across the canvas. His uncle owned a Grainger hardware store. Words like ‘‘socket,’’ ‘‘pineboard’’ and ‘‘electrician’’ recur in his paintings.

‘‘You have character,’’ the instructor said. ‘‘That’s what’s great about your drawings. I can always tell it’s you. You have a signature style.’’

Over the black words, now a smudged nimbus, Miller painted, in green, ‘‘Home.’’

‘‘Home?’’ the instructor asked.

‘‘Home Depot,’’ Miller said.

When he finished a canvas, which took about 20 minutes, he chanted the word ‘‘paper’’ until the instructor brought him a new canvas, at which point Miller immediately began again.

Downstairs, Peter Salsman, an amiable former racecar driver who bears some resemblance to Kurt Vonnegut, was showing slides of his flowerpots on his iPad. The ceramic pots are decorated with irises, passionflowers and roses.

Photo

Monica Valentine. Credit Jeff Minton for The New York Times Salsman’s voice lowered. ‘‘I’m one of God’s angels,’’ he said. ‘‘I’ve been dead three times. I go to work at nighttime for God. I put people in the right place.’’

He paused.

‘‘God calls on me when I’m sleeping. If someone dies, I have to go collect them. Like when Classie passed away here, I went and picked her up in my ’55 Chevy.’’

Salsman pressed one hand to his temple.

‘‘I really take them to heaven and to hell. I have to go wherever I’m sent. It’s a lot of responsibility. Too much.’’

Miller appeared on the other side of the studio, accompanied by a staff member.

‘‘Costs a lot of money, right?’’ Miller said.

‘‘Yes,’’ she said. ‘‘It costs a lot of money.’’

‘‘Costs a lot of money, right?’’

‘‘Yes, Danny, it does.’’

Though some artists at Creative Growth do not understand that their work is sold at all, many know exactly how much their work is selling, or not selling. This introduces a new motivation into the studio. One artist mentioned that he had begun to paint trees because they were selling well. Another, disappointed by the quality of her ceramic sculptures, recommitted herself after she sold one. A third was so discouraged when her paintings didn’t sell that she gave up the medium. John Martin lies somewhere in the middle. He looks forward to the first of the month, when he receives his check for art sales, and complains about being broke. But the physical check itself means nothing to him. ‘‘What am I supposed to do with this?’’ he says. Sometimes he tears the check up.

What does the money do to the artists? The romantic view of a self-trained artist is one whose work, like Henry Darger’s, is not discovered until after his death. But when artists understand that their work is being appraised and sold in a marketplace, is such an arrangement still ‘‘pure’’? Does the artist’s awareness of the market compromise the value of the art itself?

To answer the question, you must first decide whether people with disabilities deserve special treatment — whether they should be shielded from the anxieties, frustrations and injustices of adult life. Disability theorists tend to agree that this sheltering impulse, while well intentioned, is a form of infantilization that denies its subjects’ humanity. The awareness of an art market that judges your work, subjectively and perhaps unfairly, can only cloud the motivations that lead Creative Growth artists to do the work they do. It leads to greed, disappointment and envy; also to affirmation, encouragement and pride. It leads, in other words, to life.

‘‘When you see a Creative Growth artist at an opening, they’re beaming because they’re accepted,’’ Beal says. ‘‘If you didn’t have that, would the engagement be as focused and sustained as it is?’’

Every artist receives a quarterly check from a common pot funded by sales of Creative Growth T-shirts and other items, an effort to counter money anxieties and to create the sense that all art has value. But some checks are bigger than others.

‘‘Money changes everything,’’ di Maria says. ‘‘But it’s also not my choice. It’s the artists’ choice, and I would never make decisions for them. If some of them want to enter the market and sign with commercial galleries or rent their own studio, it’s not my job to stand in the way. It may be that Creative Growth was a nice 40-year experiment and, in the future, it won’t need to continue.’’

It was the opening night of a new Creative Growth exhibition, ‘‘Parting Is Such Sorrow Until We Meet Again Tomorrow.’’ Included were elegiac portraits of Classie; paintings of trains and buses and bridges; a bright drawing in Prismacolor pencils by George Wilson of a crowd waving to a departing cruise ship; and several of John Martin’s flip-phone sculptures, made of wood.

Several artists had been asked to stay later than usual so that they could discuss their work. In exchange, they received envelopes containing $25. The attendees — among them professional artists, Berkeley art historians and wealthy collectors from San Mateo County in matching pastel outfits — inspected the work and chatted with di Maria. Occasionally a patron approached one of the artists (‘‘Show me which of these are yours.’’ ‘‘How did you get the idea to do that?’’), but most of the time the artists stood around uncertainly. Wilson, whether out of excitement or agitation or joy, began dancing to the music in the middle of the floor. It was a swaying, jittery kind of dance, like hula-hooping without the hoop.

Finally, it was too much. Wilson shot through the crowd, out of the gallery and into the darkened studio. A staff member followed him. Wilson sat at the nearest worktable and waited. The staffer retrieved Wilson’s current work in progress and his Prismacolor pencils and set them before him. For the next two hours, while in the adjacent room the music played, glasses of wine were poured and patrons discussed the art and the artists, Wilson drew.

0 notes

Photo

#The Land Before Time#The Land Before Time II The Great Valley Adventure#The Land Before Time III The Time of the Great Giving#The Land Before Time IV Journey Through the Mists#Roy Allen Smith#Dev Ross#Judy Freudberg#Tony Geiss#Don Bluth#Stu Krieger#John Loy#John Ludin#MCA Universal Home Video#90s

51 notes

·

View notes

Photo

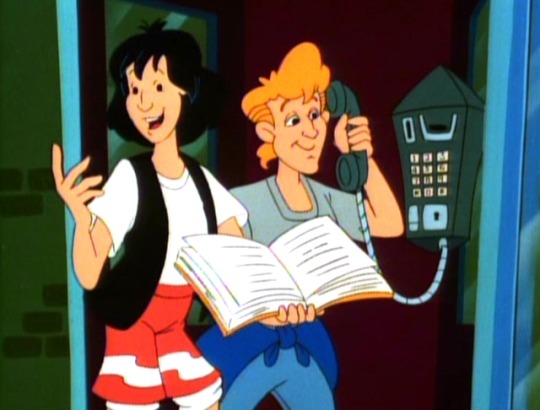

Bill & Ted's Excellent Adventures

#Bill & Ted's Excellent Adventures#Bill & Ted#Keanu Reeves#Alex Winter#One Sweet and Sour Chinese Adventure to Go#John Ludin#John Loy#Gordon Kent#Robert Alvarez#Don Lusk#Paul Sommer#Carl Urbano#Ray Patterson

212 notes

·

View notes

Photo

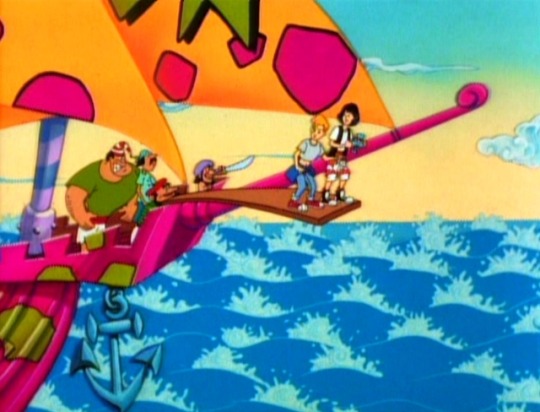

Bill & Ted's Excellent Adventures

#One Sweet and Sour Chinese Adventure to Go#John Ludin#John Loy#Gordon Kent#Robert Alvarez#Don Lusk#Paul Sommer#Carl Urbano#Ray Patterson#Keanu Reeves#Alex Winter#Bill & Ted#Bill & Ted's Excellent Adventures

112 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Bill & Ted's Excellent Adventures

#Bill & Ted's Excellent Adventures#Bill & Ted#Keanu Reeves#Alex Winter#One Sweet and Sour Chinese Adventure to Go#John Ludin#John Loy#Gordon Kent#Robert Alvarez#Don Lusk#Paul Sommer#Carl Urbano#Ray Patterson

76 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Bill & Ted's Excellent Adventures

#Bill & Ted's Excellent Adventures#Bill & Ted#Keanu Reeves#Alex Winter#One Sweet and Sour Chinese Adventure to Go#John Ludin#John Loy#Gordon Kent#Robert Alvarez#Don Lusk#Paul Sommer#Carl Urbano#Ray Patterson

29 notes

·

View notes