#Karl von Freyburg

Text

THIS DAY IN GAY HISTORY

based on: The White Crane Institute's 'Gay Wisdom', Gay Birthdays, Gay For Today, Famous GLBT, glbt-Gay Encylopedia, Today in Gay History, Wikipedia, and more … January 4

1750 – France Bruno Lenoir and Jean Diot are caught having sex in public for which they are arrested. A year later they were executed. There was general surprise in France at the severity of their sentence. Their execution was the last in France for consensual sodomy.

1877 – Marsden Hartley (d.1943) was an American Modernist painter, poet, and essayist. Hartley was born in Lewiston, Maine, where his English parents had settled.

In 1898, at age 22, Hartley moved to New York City to study painting at the New York School of Art. Hartley was a great admirer of Albert Pinkham Ryder and visited his studio in Greenwich Village as often as possible. His friendship with Ryder inspired Hartley to view art as a spiritual quest.

Hartley first traveled to Europe in April 1912, and he became acquainted with Gertude Stein's circle of avante-garde writers and artists in Paris. Stein, along with Hart Crane and Sherwood Anderson, encouraged Hartley to write as well as paint.

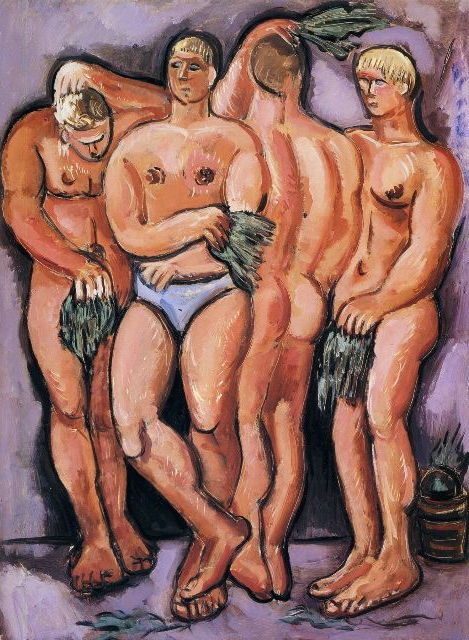

Finnish-Yankee sauna

In 1913, Hartley moved to Berlin, where he continued to paint. Many of Hartley's Berlin paintings were further inspired by the German military pageantry then on display, though his view of this subject changed after the outbreak of World War I, once war was no longer "a romantic but a real reality." The earliest of his Berlin paintings were shown in the landmark 1913 Armory Show in New York.

In Berlin, Hartley developed a close relationship with a Prussian lieutenant, Karl von Freyburg, who was the cousin of Hartley's friend Arnold Ronnebeck. References to Freyburg were a recurring motif in Hartley's work, most notably in Portrait of a German Officer (1914). Freyburg's subsequent death during the war hit Hartley hard, and he afterward idealized their relationship. Many scholars believe Hartley to have been gay, and have interpreted his work regarding Freyburg as embodying his homosexual feelings for him.

In addition to being considered one of the foremost American painters of the first half of the 20th century, Hartley also wrote poems, essays, and stories.

Cleophas and His Own: A North Atlantic Tragedy is a story based on two periods he spent in 1935 and 1936 with the Mason family in the Lunenburg County, Nova Scotia, fishing community of East Point Island. Hartley, then in his late 50s, found there both an innocent, unrestrained love and the sense of family he had been seeking since his unhappy childhood in Maine. The impact of this experience lasted until his death in 1943 and helped widen the scope of his mature works, which included numerous portrayals of the Masons.

He wrote of the Masons, "Five magnificent chapters out of an amazing, human book, these beautiful human beings, loving, tender, strong, courageous, dutiful, kind, so like the salt of the sea, the grit of the earth, the sheer face of the cliff." In Cleophas and His Own, written in Nova Scotia in the fall of 1936, Hartley expresses his immense grief at the tragic drowning of the Mason sons. The independent filmmaker Michael Maglaras has created a feature film Cleophas and His Own, released in 2005, which uses a personal testament by Hartley as its screenplay.

1946 – Arthur Conley aka Lee Roberts (d.2003) was a U.S. soul singer, best known for the 1967 hit "Sweet Soul Music".

Conley was born in McIntosh County, Georgia, U.S., and grew up in Atlanta. He first recorded in 1959 as the lead singer of Arthur & the Corvets. With this group, he released three singles in 1963 and 1964 – "Poor Girl", "I Believe", and "Flossie Mae" – on the Atlanta based record label, National Recording Company.

In 1964, he moved to a new label (Baltimore's Ru-Jac Records) and released "I'm a Lonely Stranger". When Otis Redding heard this, he asked Conley to record a new version, which was released on Redding's own fledgling label Jotis Records, as only its second release. Conley met Redding in 1967. Together they rewrote the Sam Cooke song "Yeah Man" into "Sweet Soul Music", which, at Redding's insistence, was released on the Atco-distributed label Fame Records, and was recorded at FAME studios in Muscle Shoals, Alabama. It proved to be a massive hit, going to the number two position on the U.S. charts and the Top Ten across much of Europe. "Sweet Soul Music" sold over one million copies, and was awarded a gold disc.

After several years of hits singles in the early 1970s, he relocated to England in 1975, and spent several years in Belgium, settling in Amsterdam (Netherlands) in spring 1977. At the beginning of 1980 he had some major performances as Lee Roberts and the Sweaters in the Ganzenhoef, Paradiso, De Melkweg and the Concertgebouw, and was highly successful. At the end of 1980 he moved to the Dutch village of Ruurlo, legally changing his name to Lee Roberts — his middle name and his mother's maiden name. He promoted new music via his Art-Con Productions company. Amongst the bands he promoted was the heavy metal band Shockwave from The Hague. A live performance on January 8, 1980, featuring Lee Roberts & the Sweaters, was released as an album entitled Soulin' in 1988.

Conley was gay, and several music writers have said that his homosexuality was a bar to greater success in the United States and one of the reasons behind his move to Europe and his eventual name change. In 2014, rock historian Ed Ward wrote, "[Conley] headed to Amsterdam and changed his name to Lee Roberts. Nobody knew 'Lee Roberts,' and at last Conley was able to live in peace with a secret he had hidden – or thought he had – for his entire career: he was gay. But nobody in Holland cared."

Conley died from intestinal cancer in Ruurlo, Netherlands aged 57 in November 2003. He was buried in Vorden.

1962 – Peter Steele , formerly Lord Petrus Steele , actually Petrus Thomas Ratajczyk , born in Brooklyn , New York, was an American musician . Steele was the singer , bassist and songwriter for the metal bands Carnivore and Type O Negative.

Known above all for his powerful bass-baritone voice, Steele first worked as a singer and bassist with the heavy metal group Fallout and then with the thrash metal band Carnivore. After Carnivore had disbanded for the time being, Steele, who was still working for the New York Park Authority at the time, founded the music group Type O Negative together with Sal Abruscato, Kenny Hickey and Josh Silver. Steele was particularly controversial in the early years of the band due to supposedly right-wing extremist ideas in the public. He himself always denied such allegations. He later created the Vinland flag , inspired by the Nordic flags and his own Scandinavian ancestors , which was henceforth to be found on the band's releases.

In August 1995, Steele, who was an imposing figure with his stature and height of 2.03 m, posed naked for the US edition of Playgirl. However, when he learned that around 75% of the readership are homosexual men, some of whom would now make advances to him and he was then exposed to the malice of the other band members and fans, he wrote the song I Like Goils (dt. I like girls ).

Peter Steele died on April 14, 2010 of complications from an aortic aneurysm . Steele's companion Sal Abruscato (formerly Type O Negative drummer) said they were in the process of getting Steele into an ambulance when he passed away before leaving the house. Before his death, Steele had been drug free for nine months and was in the process of making plans for a new Type O Negative album.

1969 – Richard Hake (d.2020) was a journalist and reporter for WNYC, where he was one of the hosts of the weekly morning program, Morning Edition.

Richard Scott Hake was born in the Bronx to Richard James Hake, a New York City police detective, and Joy Mekland, a clerical worker and secretary. He graduated from Carmel High School in 1987, then from Fordham University in 1991, and began working at NPR in 1991 while still at Fordham. He became a news host and reporter at WNYC in 1992. He was openly gay.

He spent 28 years working as a radio news host, reporter, and producer. He featured on several local and national NPR programs, such as Morning Edition (which he hosted), Weekend Edition, All Things Considered, and On the Media. He also broadcast on MTV, the BBC, WCBS, WBGO, WOR, and WFUV radio. Hake hosted for MTV's Logo Network's The Advocate News magazine program. His documentary work includes "The Perfume of the Bronx" and the "Coney Island Cyclone Anniversary."

For his reporting, Hake was awarded accolades from the Associated Press Broadcasters Association and the Society of Professional Journalists. Hake made his Broadway debut as a chimney sweep in Mary Poppins.

In his Twitter profile, Hake noted his unique role in the bustling Big Apple, writing: "I wake people up and tell them stories on the alarm clock, the app, streaming, in the shower, in the car, etc."

As coronavirus cases surged in the city and officials told office workers to stay home, Hake set up a makeshift studio in his one-bedroom apartment, complete with an art deco "on air" light and various microphone flags bearing the station's logos over the years.

Hake died on April 24, 2020, at age 51, in his Upper East Side home. His manner of death was ruled to be a result of an accident, according to the City's Medical Examiner.

1970 – Christopher Klucsarits, better known as Chris Kanyon (d.2010), US Professional wrestler, best known for his work in World Championship Wrestling and the World Wrestling Federation, under the ring names Kanyon and Mortis.

In 2006, after Kanyon's release from WWE, he began a gimmick in which he was an openly homosexual pro wrestler. This included a publicity stunt wherein he stated that WWE released him from his contract because of his sexuality. Kanyon later told reporters and even stated on a number of radio interviews, that this was just a publicity stunt and he was heterosexual. However, he later retracted these statements and acknowledged that he was in fact homosexual.

Before his death Kanyon was working on a book, Wrestling Reality, with Ryan Clark. The book was released November 1, 2011, and it features Kanyon's struggles as a closeted gay man as a prominent theme.

1984 – Illinois repeals its "lewd fondling or caress" law, more than two decades after repealing its sodomy law.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Robert Indiana (New Castle, 1928 - Vinalhaven, 2018) Indiana in Lewiston - The Hartley Elegies: Berlin Series, Karl von Freyburg II, 1991. - source Bertolami.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Portrait of a German Officer. Marsden Hartley. c. 1914 C.E. Oil on canvas.

Hartley’s composition is an abstract portrait of Karl von Freyburg, a Prussian lieutenant whom the artist loved and who died in the war. Von Freyburg is portrayed symbolically with the initials, "K.v.F."; his regiment number, 4; his age at death, 24; and the Iron Cross that he received posthumously. (x)

#marsden hartley#art history#oil#painting#canvas#artist: american#LGBTQ+ artist#cubism#german expressionism#portrait#abstract#Karl von Freyburg#peach tag

28 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Marsden Hartley (americano, 1877-1943). Retrato de um oficial alemão , 1914. Óleo sobre tela, 68 1/4 x 41 3/8 in (173,4 x 105,1 cm). Museu Metropolitano de Arte, Nova York, Coleção Alfred Stieglitz, 1949 (49.70.42) Em 1912, Hartley fez sua viagem inaugural para a Europa - primeiro para Paris, depois para Berlim, onde ficou fascinado com a energia e a ostentação da Alemanha Guilhermina e seus desfiles militares de amarrar jovens soldados. Lá ele conheceu e se apaixonou por Karl von Freyburg, um soldado prussiano que morreria no primeiro ano da Primeira Guerra Mundial. Após a morte de von Freyburg, a visão de Hartley sobre a guerra se transformou em perdas tristes, exemplificadas por vários quadros - a série Motivo da Guerra - na qual o artista recordou Von Freyburg usando uma linguagem codificada que inclui símbolos e padrões militares despretensiosos. O maior deles é, sem dúvida, o retrato de um oficial alemão , um memorial em tamanho natural de Von Freyburg pintado na mistura exclusiva de Hartley do Cubismo Sintético e do Expressionismo Alemão. Encontrado dentro da pintura são iniciais do oficial, "KvF"; "4", o regimento militar em que ele serviu; "24", a idade em que ele morreu; uma Cruz de Ferro, com a qual ele havia sido homenageado pouco antes de sua morte; e um tabuleiro de xadrez, em referência ao jogo favorito de von Freyburg. Hartley retornou aos Estados Unidos em 1915 devido aos horrores crescentes da guerra, eventualmente retornando a seu estado natal de Maine.. Como o clima em relação às minorias sexuais nos Estados Unidos era mais conservador que o de Berlim, Hartley passou o resto de sua carreira observando e pintando - provavelmente apenas à distância - os pescadores, salva-vidas e trabalhadores de sua cidade costeira, onde ele permaneceu até sua morte em 1943.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

whitneymuseumofart

Marsden Hartley (1877-1943)

Painting, Number 5, 1914-1915

oil on canvas, 39 1/4″ × 32"

“Marsden Hartley created Painting, Number 5, one of a series of War Motifs, during an extended stay in Berlin. Hartley was fascinated by the military pageantry of pre-war imperial Germany, and fragments of flags, banners, medals, and insignia crowd the surface of his canvases. "The military life adds so much in the way of a sense of perpetual gaiety here in Berlin," he wrote in 1913. The outbreak of World War I deeply troubled Hartley, however, and he was devastated by the death of Karl von Freyburg, a young German lieutenant with whom he had fallen in love. This work blends the splintered abstraction of Cubism with the mystical overtones of German Expressionism to conjure a symbolic portrait of Hartley’s fallen friend: included are an Iron Cross medal, epaulets, and brass buttons from his uniform, a chessboard that refers to his favorite game, and the number eight, a symbol of transcendence.”

0 notes

Text

Hyperallergic: Marsden Hartley’s Maine: His Own Private Germany

Marsden Hartley, “Log Jam, Penobscot Bay” (1940–41), oil on hardboard (masonite), 30 1/16 x 40 15/16 inches, Detroit Institute of Arts, Gift of Robert H. Tannahill (all images courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Marsden Hartley’s Maine, accompanying an exhibition at the Met Breuer, is as tantalizing for what it omits as for the insights it offers into Hartley’s creative intelligence. Focusing almost exclusively on works made in Maine — early and late land- and seascapes and some figure paintings, with few works from the intervening decades — the show offers a mainline dose of Hartley’s characteristic landscape motifs — most importantly, mountains — and approach to composition.

Whether employing the vibrant “stitched” brushwork of the early paintings or the interlocking, blocky and sinuous forms of the later works, Hartley layers elements to lock in the mass of a mountainside, a logjam pileup, or crashing waves between more or less narrow registers of sky above a rocky shore, lake, or valley below. There is a sense of compression, of barely contained energy, in many of his best works, both landscapes and figures, though he is also able to convey serenity, if only that of a sleeping volcano.

The exhibition most obviously neglects the paintings Hartley made between early 1913 and the end of 1915 while he was visiting and living in Germany. Those works culminate with the remarkable “war motif” paintings done in Berlin, which include the Metropolitan Museum’s masterpiece, “Portrait of a German Officer” (1914), a memorial to Hartley’s beloved friend, possibly lover, Lieutenant Karl von Freyburg, killed in battle in October 1914. These powerful and original syntheses of Synthetic Cubism and Expressionism — enlivened by his encounters with Robert Delaunay, in Paris, and, with the Blaue Reiter group in and around Munich, including Wassily Kandinsky, Gabriele Münter, August Macke, and Franz Marc — founded Hartley’s reputation as a modernist innovator. But they also cast into the shadows Hartley’s notionally more traditional mountain and ocean views, as they dominated assessments of his achievement from shortly after his death, in 1943, until the 1980 Whitney Museum retrospective that reignited interest in his wider career.

Marsden Hartley, “The Wave” (1940-1941), oil on masonite-type hardboard 30 1/4 x 40 7/8 inches, Worcester Art Museum

The exhibition’s publication, Marsden Hartley’s Maine, is effectively an extension of the catalogue accompanying Hartley’s 2003 retrospective at Hartford’s Wadsworth Atheneum, organized by Elizabeth Mankin Kornhauser. Two of the present book’s three principal essayists, art historian Donna M. Cassidy and Met curator Randall R. Griffey, contributed to the Wadsworth catalogue, in which the late Maine landscapes are represented sparsely, though their importance is noted. Kornhauser might have been commissioning the present book when she wrote, “One of the most prolific and successful periods of [Hartley’s] career, his last eight years in Maine, requires focused attention and new thinking. Little concern has been paid to his working methods and materials despite the fact that he is acknowledged to have been a brilliant colorist and an adroit painter.” Besides examining in-depth both the early and late Maine periods, the present book includes a fine essay on materials and techniques, based on careful examination of a dozen works, which shows a surprising continuity in composition and methods across Hartley’s career.

The show feels like a regional museum production, and it is a collaboration between the Met and the art museum at Colby College in Waterville, Maine. But the book also is redolent of regionalism of a different sort, the type that dominated American art in the later 1930s, in response to which Hartley promoted himself, in 1937, as “the painter from Maine.” Visitors to the exhibition are likely to come away with the uncomplicated idea that Hartley was what he advertised himself to be, and the book in part promotes this, opening with a chronology which mentions little about Hartley’s career aside from Maine-related aspects.

Marsden Hartley, “The Silence of High Noon–Midsummer” (ca. 1907–08), oil on canvas, 30 1/2 x 30 1/2 inches, collection of Jan T. and Marica Vilcek, Promised Gift to The Vilcek Foundation

Yet, like its hero, the book is conflicted about the identification of the artist with Maine. Following the chronology, there is an unusual three-author “Introduction” by the book’s main essayists, Cassidy, Griffey, and Colby Museum curator Elizabeth Finch. On the one hand, they buy into Hartley’s late career metamorphosis into a Maine native; on the other — in a more muted voice — they acknowledge the ambition and careerism that prompted Hartley, with a blithe disregard of his own history, to embrace a state where he never established a home, actually or emotionally, after abandoning the place as a young artist. Griffey is most forthcoming in his critical assessment of Hartley. The “reassuring narrative” of the artist fulfilling his destiny by returning to his native Maine woods in the shadow of Mt. Katahdin, Griffey writes, “has served as a frame through which many have interpreted Hartley’s late career as coming full circle” from his early Maine work. “However, a more critical assessment of his public identity as the painter from Maine reveals it to have been a gradual, indirect, even strategic process marked by contradiction and ambivalence as much as by profound connection and spiritual revelation.”

The intertwined issues of “authentic” American culture, homosexuality, and primitivism play out spectacularly during Hartley’s halcyon years in Berlin and they return in the 1930s. Besides nativism, that era is known for a resurgence of homosexual repression. (Thomas Hart Benton, the leading Regionalist, was notorious for his anti-gay diatribes.) It was a period of tremendous tension in the art world. Hartley’s supporter William Carlos Williams witnessed it and wrote, “two cultural elements were left battling for supremacy, one looking toward Europe, necessitous but retrograde in its tendency — though not wholly so by any means — and the other forward-looking but under a shadow from the first. They constituted two great bands of effort, which it would take a Titan to bring together and weld into one again.”

Marsden Hartley, “Madawaska—Acadian Light-Heavy” (1940), oil on hardboard (masonite), 40 x 30 inches, the Art Institute of Chicago. Bequest of A. James Speyer, 1987.249

Champion of “the American grain,” Williams means “forward-looking” toward America, but the footloose, cosmopolitan, homosexual Hartley had to be a Janus, looking both ways, and he needed to assume multiple masks to fit the role of the hardy, hyper-masculine Maine painter. Setting aside careerist calculation, Hartley did also subscribe to some degree (as did Williams and their friend Ezra Pound) to the racist and populist impulses behind the Regionalism.

Hartley was enthralled by Germany when he first visited — Berlin was then famous for its liberal attitude toward homosexuality, which was widespread in the military and the court of pageantry-loving Kaiser Wilhelm, who is thought to have been bisexual. Hartley wrote his financial backer and dealer, Alfred Stieglitz, that he “lived rather gayly in the Berlin fashion — with all that implies.” Germany felt like home — perhaps the only place in his adult life that could make that claim. In 1933, while staying in Bavaria, he wrote an autobiography, unpublished until 1996, in which he stated, “A week in Berlin made me feel that one had come home — and it is easy to see what four years of constant living there has done. I always feel I am coming home when I get into Germany, quite as I used to feel when I crossed the line of the State of Maine at South Berwick — I always knew I was in New England.”

Hartley was smitten from the first. Accordingly, this critically acute artist could be willfully blind to the political implications of situations he encountered, for example, German militarism. “Of course the military system is accountable for many things,” he wrote in a letter to Rockwell Kent, “and to some this military element is objectionable—but it stimulates my child’s love for the public spectacle — and such wonderful specimens of health these men are — thousands all so blond and radiant.”

In the 1920s Hartley spent considerable time in Europe; in the 1933 text he recalls a 1922 visit to Florence. “But I knew nothing of Fascismo then — and little about it now — save that being in Germany or Bavaria at the moment and seeming somehow to look like a native — is it my fine green plush hat — I bought in Paris in 1913 — and never found a real place to wear it until this year? Or is it my mountain cape, or is it both? But I get the N.S.D.A.P. salute” — the Hitler salute —“very often and never know quite what to do — because in quite the same way I never can cross myself in a Catholic Church and I frequently go in them — especially in Europe.” Art historian Gail Levin, in the catalogue for a show of Hartley’s Bavarian work, reports that at one point, the artist had the idea of asking a Nazi friend to introduce him to Hitler, who, according to Hartley, was “from all accounts” a “nice person, and, of course having wanted to be an artist, he likes artists.”

Marsden Hartley, “City Point, Vinalhaven” (1937–38), oil on commercially prepared paperboard (academy board), 18 1/4 x 24 3/8 inches, Colby College Museum of Art, Waterville, Gift of the Alex Katz Foundation, 2008.214

Hartley’s strange combination of ambition, vanity, erotic attraction, and childlike naiveté underlies his response to Dürer’s famous self-portrait at the age of 28, painted in 1500, which Hartley saw in 1933, descending from the mountains to visit Munich’s Alte Pinakothek. He said of Dürer that he seemed “to have all that the eye can have, he saw things exactly as they were, he knew how to convey that impression. … I would like to make a painting of a mountain and have it have all that this portrait has ….”

His comments on the Dürer suggest that he understood the late landscapes to be conceptual self-portraits, with landscape elements standing in for personal qualities, just as the insignia, banners, helmet, and initials of the painting “Portrait of a German Officer” stand in for his lost lover. But he took the idea of symbolic portraits (a concept he shared with the circle of artists he knew in the teens, including Marcel Duchamp, Francis Picabia, and Charles Demuth) and naturalized it, rooting the symbolic portrait in his own memory and experience, not in publicly shared motifs.

Like his regionalist sentiments, the bold primitivism of Hartley’s work is largely a construction. In his first German period, he was already signifying “nativeness” in an embarrassingly flatfooted way, drawing on clichéd American Indian motifs for his odd Amerika series, painted in Berlin at a time when he had never encountered Native Americans. In later work he graduates to styles signifying primitiveness and authenticity, assimilated from artists as different as the untutored John Kane, Georges Rouault, and perhaps Max Beckmann. But as in his German masterpieces, he always had a powerful ability to synthesize style, technique, politics, and desire, subordinating them to a unique vision, his own private Maine. Or Germany.

Marsden Hartley’s Maine continues at the Met Breuer (945 Madison Avenue, Upper East Side, Manhattan) through June 18.

The exhibition’s catalogue is published by the Metropolitan Museum of Art and is available from Amazon and other online booksellers.

The post Marsden Hartley’s Maine: His Own Private Germany appeared first on Hyperallergic.

from Hyperallergic http://ift.tt/2ozvPjs

via IFTTT

0 notes

Photo

Image Courtesy of The Met

Marsden Hartley, Portrait of a German Officer

During the week of orientation, Studio in a School took us to many museums to explore the world of art in the many different perspectives of artists around the world. One museum in particular that stuck into my head was The Metropolitan Museum of Art. This museum gave the viewers an image of what art from ancient to modern times looks like all over the world.

There was this one piece that is still in my mind from that day. It’s called Portrait of a German Officer painted by Marsden Hartley. When I first walked to this art piece, I really didn’t understand why the title called it portrait. I thought “Portrait? How is this a portrait if it doesn’t have a drawing of a face?’’ The definition of a portrait is that it is a painting, photograph, sculpture, or other artistic representation of a person. Forgetting all about the fact that there isn’t any sort of face hidden in the picture, but the representation of a person. This thought just went around my mind for a while, until we thoroughly went over this piece with the tour guide.

By talking about this artwork, I realized what Hartley was trying to capture. This portrait is a symbol to his loved one Karl von Freyburg, who went to war and passed away. With all the dull colors, you can tell that Hartley felt lots of emotion towards this painting. He shows the flags from the Freyburg’s home nations and symbols of war, such as cross arrows, swords, and bombs. The brushstrokes don’t go in one direction but flow in different directions. The composition represents Freyburg; the KVF is his initials; the 4 is his reign number; the 24 is his age. The objects altogether look like a coffin, showing that there is death involved.

Looking at this portrait from my perspective, I felt like Hartley had sad emotions during this. His friend died at war and he just couldn’t bear it. Hartley must have had a relationship that made him feel this way, as shown by the small and soft brush strokes and the colors that he was using. This artwork inspired me by teaching me that a portrait doesn’t necessarily have to be a drawn face or object, but it can be a collaboration of objects that represent something far more important.

This portrait has made me think lately about friendship. Friendship was so important to Hartley that he decided to make an art piece out of it. He showed honor of his friendship toward this German officer.

0 notes

Text

In 1912, Marsden Hartley made his maiden voyage to Europe—first to Paris, then to Berlin, where he became enthralled with the energy and pageantry of Wilhelmine Germany and its military parades of strapping young soldiers. There he met and fell in love with Karl von Freyburg, a Prussian soldier who was to die in the first year of World War I. After von Freyburg's death, Hartley's view of the war turned to mournful loss, exemplified by a number of paintings—the “War Motif” series—in which the artist memorialized von Freyburg using a coded language comprising otherwise unassuming military symbols and patterns.

Learn about more artworks by queer artists in The Met’s collection in a recent blog post: https://met.org/2LdAwet

Featured Artwork of the Day: Marsden Hartley (American, 1877–1943) | Portrait of a German Officer | 1914

0 notes

Text

Hyperallergic: American Artists’ Fraught Responses to the First World War

Installation view of World War I and American Art at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (photo courtesy the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia)

PHILADELPHIA — When war broke out in Europe in August 1914, the United States declared neutrality. President Woodrow Wilson feared that entering the conflict would cause civil unrest at home as many United States citizens had come from the nations that were now at war. In the end, the US was only officially active in World War I for 18 months, from April 1917 to November 1918, but as the exhibition World War I and American Art at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts argues, the Great War had a deep and complicated impact on American artists both before and after the country entered the conflict, pushing them to change their visual language as they debated, promoted, and processed the historical events.

Marsden Hartley, “Portrait” (ca 1914–15), oil on canvas, 32 1/4 × 21 1/2 in, the Collection of the Frederick R. Weisman Art Museum at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, bequest of Hudson D. Walker from the Ione and Hudson D. Walker Collection

The exhibition begins in 1914, when much of the country was apprehensive about participating in the conflict, even though the US’s economic bias leaned heavily toward the Allies. Such split allegiances are explored through the pairing of Childe Hassam and Marsden Hartley. Painting in New York, Hassam depicted patriotic, impressionist cityscapes filled with American and Allied flags; while living in Berlin, Hartley created a series of elegiac images in memory of his lover Karl von Freyburg, a German military officer. Though Hartley claimed his work was neither pro-German, nor political, his moving images capture the conflicted emotions of one mourning the loss of a forbidden love.

Childe Hassam, “Flags on 57th Street, Winter 1918 (1918), oil on canvas, 35 3/4 × 23 3/4 in, the New-York Historical Society, bequest of Julia B. Engel (photo © the New-York Historical Society)

American neutrality was tested as early as 1915, when German U-boats attacked the British passenger ship the Lusitania, killing nearly 1,200 people on board, including 128 US citizens. The attack outraged the American public and became a popular subject for artists, like Winsor McCay, who attempted to record the event based on first-hand accounts in his short animated film “The Sinking of Lusitania” (1918), which depicts the shocking speed with which the ship sank, as bodies fall over the sides in an unending cascade. For interest groups attempting to gather US support for the Allies, the incident became a rallying cry, as is evident in Fred Spear’s poster “Enlist” (1915). Commissioned and printed by the Boston Committee for Public Safety, the poster tapped into the belief that the incident had been an attack on innocent lives, showing a mother and child caught in a tender embrace as they drown in the cold ocean.

Henry Glintenkamp, “Physically Fit” (1917), published in The Masses, October 1917, crayon and India ink on board, 20 7/8 × 16 1/2 in, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, Prints and Photographs Division

After the United States entered the war in 1917, the government used art to establish a powerful media environment saturated with seductive, sentimental, and nationalist propaganda. In much of the imagery, the Axis enemies are barbaric apes and murderous fiends, while US soldiers are strong, sexy, and clean, adored by their loving wives and children who stay at home and buy war bonds. Yet participation in World War I was deeply unpopular among US citizens, and political cartoons published in The Masses, such as Henry Glintenkamp’s “Physically Fit” (1917), liken the draft to a death sentence, as a skeleton measures a fit young man for a coffin. These critical opinions, however, were quickly silenced through official censorship efforts, which criminalized anti-war speech and encouraged people to spy on their neighbors. These laws prompted citizens to focus on the enemy “within,” partially in an attempt to convince the American public that the war was not just, as the famous song says, “over there.”

Charles Burchfield, “The East Wind” (1918), watercolor on paper, 18 x 22 1/2 in, Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York, bequest of A. Conger Goodyear, 1966 (photo courtesy Albright-Knox Art Gallery/Art Resource, NY)

Georgia O’Keeffe, “The Flag” (1918), watercolor on paper, 11 15/16 × 8 3/16 in, Milwaukee Art Museum, gift of Mrs. Harry Lynde Bradley (© 2016 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/Artists Rights Society, ARS, New York; photo by Larry Sanders)

Despite strict censorship, apprehension about the war is still evident in the contemporaneous canvases of many American artists. The young Charles Burchfield recorded his growing fear of having to fight in his diaries as he waited for his draft number to be called. Although he later denied that the war had affected his imagery, it is impossible not to see his mounting anxiety in “The East Wind” (1918), in which a large, skull-like form threatens to envelop a vulnerable house. The war found its way into the work of Georgia O’Keeffe in a more mournful and conflicted manner. Her younger brother Alexis enlisted almost immediately after the US joined the conflict, and she found herself both confused by and in awe of his devout patriotism. Executed in 1918, O’Keeffe’s “The Flag” shows a red flag against a deep blue sky, which seems to seep into and overcome it. Throughout the war, red flags were commonly raised at socialist and anarchist meetings, where pacifism and obstructing the draft were often discussed, and with this in mind, the work seems to evoke the battle between O’Keeffe’s red apprehension and her brother’s true blue allegiance.

Installation view of World War I and American Art at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts featuring “Gassed” (1919) by John SInger Sargent (photo courtesy the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia)

The unique skills of artists were also put to work as part of the official war effort. Edward Steichen, for example, was made chief of the photographic section of the American Expeditionary Forces, while Burchfield designed camouflage, and others made medical drawings and drew maps. In 1918, the British government commissioned John Singer Sargent to make a picture that captured Anglo-American cooperation on the front. After spending three-months in France, the artist decided to portray a harrowing sight — a line of gassed and blindfolded men. Despite the tragedy of its subject matter, Sargent’s “Gassed” (1919) holds fast to the Edwardian idea that war is noble. Though wounded, the soldiers still grasp their rifles; though blind, they walk in ordered formation. In marked contrast, George Bellows showed the war to be marred by dishonor. Unable to fight because of his age, Bellows never saw the conflict in Europe and, ironically, the former champion of visual journalism based his depictions solely on articles and published reports. In a series of lithographs inspired by the Bryce Report, Bellows portrays in lurid detail the war crimes committed by the German army as they marched through neutral Belgium in 1914: woman are raped, families are murdered, and babies are skewered on bayonets.

The question of what it means to be a witness and to depict the experience of war is woven through the exhibition. Artists like Claggett Wilson and Horace Pippin went to France not to draw but to fight and both only depicted the conflict after they had been wounded, relying on memories that haunted them. The realism in Wilson’s watercolors encompasses more than mere description, mining the psychological dimensions of the conflict: soldiers march across fields of grass that have turned yellow under the mustard gas and a line of ghostly enemy soldiers wearing gas masks appears in the purple mist beyond an expanse of twisted barbed wire. Wilson also paired each image with a description of the memory he depicted, for, as one captions says, he was trying to capture “not how it looks but how it feels and sounds and smells.”

Claggett Wilson, “Dance of Death” (ca 1919), watercolor and pencil on paperboard, 16 3/4 × 22 1/2 in, Smithsonian American Art Museum, gift of Alice H. Rossin (photo clourtesy Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC / Art Resource, NY)

Horace Pippin, “The End of the War: Starting Home” (1930–33), oil on canvas, 26 × 30 1/16 in, Philadelphia Museum of Art, gift of Robert Carlen, 1941

Pippin completed “The End of the War: Starting Home” (1930–33) more than a decade after returning to the United States from the battlefields in France, and the painting condenses the traumatic wartime experiences documented in his journals into a single chaotic composition. At center, amid the melee, a white German solider, raising his arms in surrender, is confronted by a black American solider wielding a bayonet. Though Pippin captures the triumph of the African American soldiers, in their dark uniforms, they almost seem to blend in with the blackened background, reminding the viewer that despite the initial flurry of homecoming glory that met the black soldiers who gallantly served their country, they were quickly made invisible by racial segregation at home.

Violet Oakley, “Henry Howard Houston Woodward” (1921), oil on canvas, 53 × 35 in, Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Philadelphia, gift of Dr. and Mrs. George Woodward

The exhibition ends with works created after the war that memorialize those who died — as seen in Violet Oakley’s portrait of the lost solider Henry Howard Houston Woodward — or question the effects of the conflict, as seen in Carl Hoeckner’s “The Homecoming of 1918” (1919), which depicts an infinite mass of emaciated and traumatized war victims. Such images clearly illustrate the fact that by the 1930s many Americans saw the United States’ participation in the conflict to be controversial and deeply flawed, leading us to question how we remember a period that cannot be reduced to a simple fight between good and evil. Many later historical accounts have recast World War I and the unstable peace that followed as merely a prelude to World War II. The exhibition at PAFA serves as a corrective of sorts to the historical accounts that downplay the complexity and importance of World War I for American artists, providing a more unsettling and honest picture of a nation’s reaction to it. Concluding with poignant images of reflection, the exhibition upends previous declarations that the Great War was ever the “Forgotten War.”

Carl Hoeckner, “The Homecoming of 1918” (1919), oil on panel, 57 × 83 3/4 in (courtesy the John & Susan Horseman Collection of American Art)

Installation view of World War I and American Art at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (photo courtesy the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia)

Laura Brey, “Enlist — On Which Side of the Window Are YOU?” (1917), poster, 39 × 26 in, courtesy of the New-York Historical Society (photo © the New-York Historical Society)

Harry Ryle Hopps, “Destroy This Mad Brute — Enlist” (1917), poster, 41 15/16 × 27 7/8 in (courtesy the Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin)

E. G. Renesch, publisher “True Blue” (1919), poster, 20 1/2 x 16 1/8 in, the Wolfsonian — Florida International University, Miami Beach, The Mitchell Wolfson Jr. Collection

World War I and American Art continues at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (118-128 North Broad Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) through April 9,

The post American Artists’ Fraught Responses to the First World War appeared first on Hyperallergic.

from Hyperallergic http://ift.tt/2ijYoOD

via IFTTT

1 note

·

View note