#LE CORBUSIER PLANS impressions

Text

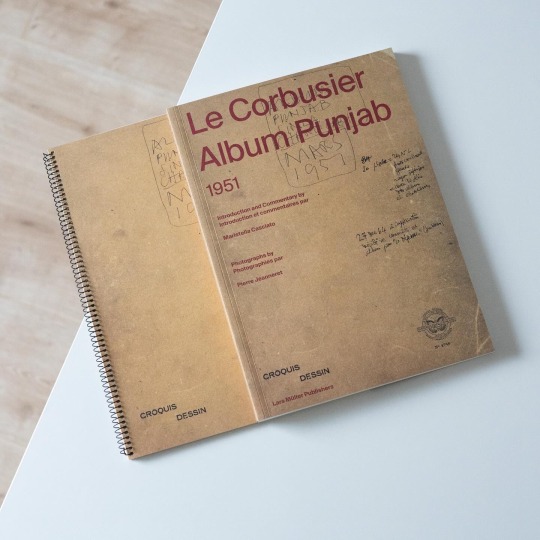

In 1951 Le Corbusier embarked on his „aventure indienne“, his Indian adventure, to design and build Chandigarh, the new capital of the Punjab. On February 20 he boarded a flight to Bombay together with his cousin Pierre Jeanneret and on February 23 the two met up with the players to be involved in the project: Maxwell Fry, engineer P.L. Varma as well as government official P.N. Thapar. At the time of their arrival at the designated site of the future capital it was a wide plain dotted with numerous villages and lush vegetation. On the same day Le Corbusier began writing and drawing in his so-called „Album Punjab“, a notebook he would continue to fill until March 11 and which today represents a unique source to the events, ideas and impressions preceding the design and construction of Chandigarh.

The „Album Punjab“ has recently been published for the first time as a facsimile by Lars Müller Publishers and is accompanied by a volume written by Maristella Casciato providing additional context to LC’s commission, unpublished photographs taken by Pierre Jeanneret during the trip and a day-by-day synopsis of the notebook.

Already the first entry tells of Corbusier’s deep interest in the existing landscape and villages, their scale and density as well as the daily life going on. At the same time he also began to search for solutions regarding water supply, spatial approaches to climate control and air circulation in residential buildings as well as he sketched a road system for the future capital and its capitol complex. Consecutively Le Corbusier elaborated these initial impressions and sketches and delved into the local architecture, the spatial organization of traditional houses and already drew planimetric arrangements of low-cost housing units. In terms of the overall urban planning LC harked back to the Pilot Plan he developed for Bogotá together with José Luis Sert. A pressing issue that also came up during the trip were construction costs and the high cost of wood which made the use of concrete even more appealing.

In view of the far-reaching insights the book provides it is an important addition to the literature on Le Corbusier and highly recommended!

#le corbusier#chandigarh#architectural drawings#architecture book#architectural history#book#modern architecture#lars müller publishers

55 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Metro “ Chistye Prudy”, Moscow

Chistye Prudy (Russian: Чи́стые пруды́, English: Clean Ponds) is a Moscow Metro station in the Basmanny District, Central Administrative Okrug, Moscow. It is on the Sokolnicheskaya Line, between Lubyanka and Krasnye Vorota stations. Chistye Prudy was opened on 15 May 1935 as a part of the first segment of the Metro. The station lies beneath Myasnitskaya Street, close to Turgenevskaya Square and the Clean Ponds, after which the station was named. It was the deepest station in Moscow Metro from 1935 until 1938.

Though planned to be a three-vaulted station with a full-length central hall (similar to Krasnye Vorota and Okhotny Ryad), Chistye Prudy was built instead according to a London Underground type design with two passages at either end of the station connecting the platforms. The outer platform vaults were finished to give the impression that a central hall did in fact exist, with what appeared to be a row of dark marble pylons. However, all of the archways except those at either end of the platform were barricaded. The architect of the initial station was Nikolai Kolli who worked with Le Corbusier on the nearby Tsentrosoyuz building.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

What is an "Ideal" city?

It’s hard to imagine an ideal city without drifting into pure fiction. Imagining a perfect city is often counterintuitive, since cities, since the dawn of civilization, have been formed as a result of human action, not human design. Still, it doesn’t mean that “imagined” urban progress should not be applied in urban environments. This idea is the basis of urban planning. The Future Planners of America have proposed three key concepts that are central to an ideal city: effective public transportation, limited environmental impact, and resistance to natural disasters through strong infrastructure.

Good public transportation is necessary to help achieve a human scale to the city as a whole. When bus lanes, subway systems, and bikeshares are emphasized and effectively implemented in urban areas, it makes these areas seem much less overwhelming. Human scale is best implemented through effective public transportation because it eliminates the need for travel on foot, one of the most helpful measurements of human scale. Ebenezer Howard’s Garden City does an impressive job at managing this scale problem. With a series of radial rail lines that connect a complex of cities. In the world, the best example of effective public transportation is Madrid, Spain. Madrid has 300 train stations, over 200 bus lines, both of which stop incredibly frequently (trains: three to four minutes, bus: five to 15 minutes); Bus and train tickets are interchangeable, allowing for flawless transition between the two; the Madrid Metro has a website that shows people the quickest connections between two places.

Madrid Metro subway car: via Sharon Hahn Darlin and Devour Tours

Low environmental impact in cities is not only important for the cities themselves, but for the rest of the world. Green cities work to secure the future for the cities’ current inhabitants and future generations. Additionally, a city free from air and water pollution is important to the physical and mental well being of its inhabitants. One of the main motivations for Le Corbusier’s “Tower’s in the Park” was to free people from the “noise, dust, congestion, noxious gasses, and disease” that plagued Industrial cities. In the real world, the most prominent example of a “green city” is Reykjavik, Iceland. Almost 100% of Reykjavik’s energy comes from renewable sources, and the high volcanic activity in the region allows 90% of households to use geothermal heating. To lower the amount of pollution from cars, neighborhoods are built with higher density to encourage cycling and walking, in addition to many bus routes and a light rail system. Reykjavik has also committed to carbon neutrality by the year 2040.

Hellisheiði Geothermal Plant. via Arni Saeberg and Reykjavik Energy

As the world changes, so do the environments which cities inhabit. A lot of times for the worse. The solution to this problem for many of a city’s inhabitants is relocation, but this is simply not a reality for most people. Instead, a strong infrastructure to fight against these environmental changes is ideal for a city. One excellent example is the city of Amsterdam, in the Netherlands. Amsterdam is the political and economic capital of the Netherlands, a place over 17 million people call home. However, Amsterdam lies seven feet below sea level and is surrounded by flat land, a perfect recipe for a devastating flood. As a result, the Netherlands have spent billions of dollars on massive sea walls and wind-powered pumps to keep the water at bay. The project has been so successful that over twenty percent of The land in the Netherlands has been reclaimed from the sea.

Oosterscheldekering Sea Wall: Rens Jacobs via Beeldbank

Debate question: All of the cities mentioned in this blog exist in the Western World, and have maintained incredible levels of wealth for centuries. Do Third World and Post-colonial nations have the means to invest into ideal cities? Why or why not?

1 note

·

View note

Text

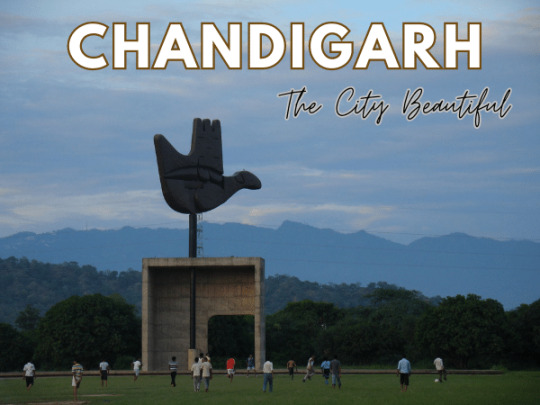

Exploring the Vibrant Charms of Chandigarh: A 3/4-Day Itinerary with Bike Rental

Chandigarh, the capital city of both Punjab and Haryana, is a well-planned and modern metropolis that seamlessly blends urban development with natural beauty. Chandigarh has a wide range of attractions for any traveller with its broad, tree-lined boulevards, beautiful gardens, and architectural wonders.

To make the most of your visit, consider bike on rent in Chandigarh, allowing you the freedom to explore the city and its surroundings at your own pace. In this blog, we present a carefully curated itinerary for a memorable 3/4-day trip, highlighting the must-visit places in and around Chandigarh.

Day 1: Exploring Chandigarh City

1. Sukhna Lake

Start your journey at the iconic Sukhna Lake, a serene water body located at the foothills of the Himalayas. Get a bike on rent in Chandigarh to reach this picturesque spot, where you can enjoy a peaceful stroll along the lakeside promenade, indulge in boating activities, or simply relax amidst nature's tranquillity.

2. Rock Garden

Next, head to the enchanting Rock Garden, a testament to human creativity and imagination. Built using recycled materials, this sprawling garden boasts numerous sculptures, pathways, and waterfalls, providing a whimsical experience. Park your Chandigarh bike rental nearby and wander through the maze of artistry that unfolds at every turn.

3. Capitol Complex

Marvel at the architectural brilliance of the Capitol Complex, designed by the renowned architect Le Corbusier. This UNESCO World Heritage Site comprises three main buildings: the Secretariat, the Legislative Assembly, and the High Court. Capture the grandeur of these structures while enjoying a leisurely bike ride around the complex.

4. Chandigarh Rose Garden

As the day winds down, visit the fragrant oasis of Chandigarh Rose Garden. Home to thousands of rose bushes in various hues, this garden is a paradise for nature lovers and photography enthusiasts. Park your rental bike and immerse yourself in the vibrant colours and enchanting fragrances that fill the air.

Day 2: Exploring the Periphery

1. Pinjore Gardens

Get on a scenic ride to Pinjore Gardens, also known as Yadavindra Gardens. Located approximately 20 kilometres from Chandigarh, this Mughal-style garden offers exquisite lawns, fountains, and historical structures. Explore the terraced gardens, capture stunning photographs, and experience the serenity of this captivating destination.

2. Nek Chand's Rock Garden

Make your way to Nek Chand's Rock Garden, an artistic marvel tucked away on the outskirts of Chandigarh. Created by Nek Chand, a government official turned artist, this sprawling garden showcases an impressive collection of sculptures, pottery, and artwork made from recycled materials. Cruise on your scooty on rent in Chandigarh to witness the unique fusion of nature and art in this hidden gem.

Day 3: Exploring Beyond Chandigarh

1. Kasauli

Get a bike on rent in Chandigarh and embark on a day trip to the charming hill station of Kasauli, nestled amidst the verdant Shivalik Range. Enjoy the cool mountain air, take leisurely walks through pine forests, and savour panoramic views of the Himalayan foothills. Kasauli offers a tranquil escape from the bustling city, and the journey itself is an adventure on two wheels.

2. Morni Hills

For those seeking a bit more adventure, ride your rental bike to Morni Hills, located about 45 kilometres from Chandigarh. This scenic hill station is known for its hiking trails, lakes, and dense forests. Immerse yourself in nature's beauty, go trekking, or indulge in boating activities at Morni Lake, leaving you with cherished memories of this hidden gem.

Conclusion

Chandigarh, with its perfect blend of modernity and natural splendour, offers a multitude of experiences for travellers. By getting a bike on rent in Chandigarh, you can navigate the city's attractions and venture beyond its borders with ease. From the serene Sukhna Lake to the artistic wonders of Rock Garden and Nek Chand's Rock Garden, there's something for everyone.

Exploring nearby destinations like Pinjore Gardens, Kasauli, and Morni Hills further enriches your journey, immersing you in the beauty of the region. So, gear up, get a bike rent Chandigarh, and embark on an unforgettable adventure through the vibrant charms of Chandigarh and its surroundings.

#bike on rent in chandigarh#scooty on rent in chandigarh#two wheeler on rent in chandigarh#monthly bike on rent in chandigarh#bike rentals in chandigarh#bike hire in chandigarh#Chandigarh bike rental price

0 notes

Note

I think I count as the mythical ancap from your post on housing and I just wanted to butt in and say: Building more homes was one of the best things the Soviet Union did. We make fun of how ugly comblocks are, but they have ROOFS, that counts.

Idk your political positions too well, but I've always gotten the impression you're more just a free-market libertarian. I feel like (and I may be stereotyping here) most people who unironically identify as anarcho-capitalists are incapable of recognizing any useful role for any government at all.

In any case, I would strongly agree. Soviet/Warsaw Pact housing policy has a reputation of being ugly and monolithic, but a) midcentury urban planning was a disaster everywhere, still recovering from the likes of Le Corbusier, and b) ugly housing is infinitely better than no housing!

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Brutalism Post Part 3: What is Brutalism? Act 1, Scene 1: The Young Smithsons

What is Brutalism? To put it concisely, Brutalism was a substyle of modernist architecture that originated in Europe during the 1950s and declined by the 1970s, known for its extensive use of reinforced concrete. Because this, of course, is an unsatisfying answer, I am going to instead tell you a story about two young people, sandwiched between two soon-to-be warring generations in architecture, who were simultaneously deeply precocious and unlucky.

It seems that in 20th century architecture there was always a power couple. American mid-century modernism had Charles and Ray Eames. Postmodernism had Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown. Brutalism had Alison and Peter Smithson, henceforth referred to simply as the Smithsons.

If you read any of the accounts of the Smithsons’ contemporaries (such as The New Brutalism by critic-historian Reyner Banham) one characteristic of the pair is constantly reiterated: at the time of their rise to fame in British and international architecture circles, the Smithsons were young. In fact, in the early 1950s, both had only recently completed architecture school at Durham University. Alison, who was five years younger, was graduating around the same time as Peter, whose studies were interrupted by the Second World War, during which he served as an engineer in India.

Alison and Peter Smithson. Image via Open.edu

At the time of the Smithsons graduation, they were leaving architecture school at a time when the upheaval the war caused in British society could still be deeply felt. Air raids had destroyed hundreds of thousands of units of housing, cultural sites and had traumatized a generation of Britons. Faced with an end to wartime international trade pacts, Britain’s financial situation was dire, and austerity prevailed in the 1940s despite the expansion of the social safety net. It was an uncertain time to be coming up in the arts, pinned at the same time between a war-torn Europe and the prosperous horizon of the 1950s.

Alison and Peter married in 1949, shortly after graduation, and, like many newly trained architects of the time, went to work for the British government, in the Smithsons’ case, the London City Council. The LCC was, in the wake of the social democratic reforms (such as the National Health Service) and Keynesian economic policies of a strong Labour government, enjoying an expanded range in power. Of particular interest to the Smithsons were the areas of city planning and council housing, two subjects that would become central to their careers.

Alison and Peter Smithson, elevations for their Soho House (described as “a house for a society that had nothing”, 1953). Image via socks-studio.

The State of British Architecture

The Smithsons, architecturally, ideologically, and aesthetically, were at the mercy of a rift in modernist architecture, the development of which was significantly disrupted by the war. The war had displaced many of its great masters, including luminaries such as the founders of the Bauhaus: Walter Gropius, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and Marcel Breuer. Britain, which was one of the slowest to adopt modernism, did not benefit as much from this diaspora as the US.

At the time of the Smithsons entry into the architectural bureaucracy, the country owed more of its architectural underpinnings to the British architects of the nineteenth century (notably the utopian socialist William Morris), precedent studies of the influences of classical architecture (especially Palladio) under the auspices of historians like Nikolaus Pevsner, as well as a preoccupation with both British and Scandinavian vernacular architecture, in a populist bent underpinned by a turn towards social democracy. This style of architecture was known as the New Humanism.

Alton East Houses by the London County Council Department of Architecture (1953-6), an example of New Humanist architecture. Image taken from The New Brutalism by Reyner Banham.

This was somewhat of a sticky situation, for the young Smithsons who, through their more recent schooling, were, unlike their elders, awed by the buildings and writing of the European modernists. The dramatic ideas for the transformation of cities as laid out by the manifestos of the CIAM (International Congresses for Modern Architecture) organized by Le Corbusier (whose book Towards a New Architecture was hugely influential at the time) and the historian-theorist Sigfried Giedion, offered visions of social transformation that allured many British architects, but especially the impassioned and idealistic Smithsons.

Of particular contribution to the legacy of the development of Brutalism was Le Corbusier, who, by the 1950s was entering the late period of his career which characterized by his use of raw concrete (in his words, béton brut), and sculptural architectural forms. The building du jour for young architects (such as Peter and Alison) was the Unité d’Habitation (1948-54), the sprawling massive housing project in Marseilles, France, that united Le Corbusier’s urban theories of dense, centralized living, his architectural dogma as laid out in Towards a New Architecture, and the embrace of the rawness and coarseness of concrete as a material, accentuated by the impression of the wooden board used to shape it into Corb’s looming, sweeping forms.

The Unité d’habitation by Le Corbusier. Image via Iantomferry (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Little did the Smithsons know that they, mere post-graduates, would have an immensely disruptive impact on the institutions they at this time so deeply admired. For now, the couple was on the eve of their first big break, their ticket out of the nation’s bureaucracy and into the limelight.

The Hunstanton School

An important post-war program, the one that gave the Smithsons their international debut, was the expansion of the British school system in 1944, particularly the establishment of the tripartite school system, which split students older than 11 into grammar schools (high schools) and secondary modern schools (technical schools). This, inevitably, stimulated a swath of school building throughout the country. There were several national competitions for architects wanting to design the new schools, and the Smithsons, eager to get their hands on a first project, gleefully applied.

For their inspiration, the Smithsons turned to Mies van der Rohe, who had recently emigrated to the United States and release to the architectural press, details of his now-famous Crown Hall of the Illinois Institute of Technology (1950). Mies’ use of steel, once relegated to being hidden as an internal structural material, could, thanks to laxness in the fire code in the state of Illinois, be exposed, transforming into an articulated, external structural material.

Crown Hall, Illinois Institute of Technology by Mies van der Rohe. Image via Arturo Duarte Jr. (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Of particular importance was the famous “Mies Corner,” consisting of two joined exposed I-beams that elegantly elided inherent problems in how to join together the raw, skeletal framing of steel and the revealing translucence of curtain-wall glass. This building, seen only through photographs by our young architects, opened up within them the possibility of both the modernist expression of a structure’s inherent function, but also as testimony to the aesthetic power of raw building materials as surfaces as well as structure.

The Smithsons, in a rather bold move for such young architects, decided to enter into a particularly contested competition for a new secondary school in Norfolk. They designed a school based on a Miesian steel-framed design of which the structural elements would all be visible. Its plan was crafted to the utmost standards of rationalist economy; its form, unlike the horizontal endlessness of Mies’ IIT, is neatly packaged into separate volumes arranged in a symmetrical way. But what was most important was the use of materials, the rawness of which is captured in the words of Reyner Banham:

“Wherever one stands within the school one sees its actual structural materials exposed, without plaster and frequently without paint. The electrical conduits, pipe-runs, and other services are exposed with equal frankness. This, indeed, is an attempt to make architecture out of the relationships of brute materials, but it is done with the very greatest self-denying restraint.”

Much to the upset and shock of the more conservative and romanticist British architectural establishment, the Smithsons’ design won.

Hunstanton School by Alison and Peter Smithson (1949-54). Photos by Anna Armstrong. (CC BY NC-SA 3.0)

The Hunstanton School, had, as much was possible in those days, gone viral in the architectural press, and very quickly catapulted the Smithsons to international fame as the precocious children of post-war Britain. Soon after, the term the Smithsons would claim as their own, Brutalism, too entered the general architectural consciousness. (By the early 1950s, the term was already escaping from its national borders and being applied to similar projects and work that emphasized raw materials and structural expression.)

The New Brutalism

So what was this New Brutalism?

The Smithsons had, even before the construction of the Hunstanton School had been finished, begun to draft amongst themselves a concept called the New Brutalism. Like many terms in art, “Brutalism” began as a joke that soon became very serious. The term New Brutalism, according to Banham, came from an in-joke amongst the Swedish architects Hans Asplund, Bengt Edman and Lennart Holm in 1950s, about drawings the latter two had drawn for a house. This had spread to England through the Swedes’ English friends, the architects Oliver Cox and Graeme Shankland, who leaked it to the Architectural Association and the Architect’s Department of the London County Council, at which Alison and Peter Smithson were still employed. According to Banham, the term had already acquired a colloquial meaning:

“Whatever Asplund meant by it, the Cox-Shankland connection seem to have used it almost exclusively to mean Modern Architecture of the more pure forms then current, especially the work of Mies van der Rohe. The most obstinate protagonists of that type of architecture at the time in London were Alison and Peter Smithson, designers of the Miesian school at Hunstanton, which is generally taken to be the first Brutalist building.”

(This is supplicated by an anecdote of how the term stuck partially because Peter was called Brutus by his peers because he bore resemblance to Roman busts of the hero, and Brutalism was a joining of “Brutus plus Alison,” which is deeply cute.)

The Smithsons began to explore the art world for corollaries to their raw, material-driven architecture. They found kindred souls in the photographer Nigel Henderson and the sculptor Edouardo Paolozzi, with whom the couple curated an exhibition called “Parallel of Life and Art.” The Smithsons were beginning to find in their work a sort of populism, regarding the untamed, almost anthropological rough textures and assemblies of materials, which the historian Kenneth Frampton jokingly called ‘the peoples’ detailing.’ Frampton described the exhibit, of which few photographs remain, as thus:

“Drawn from news photos and arcane archaeological, anthropological, and zoological sources, many of these images [quoting Banham] ‘offered scenes of violence and distorted or anti-aesthetic views of the human figure, and all had a coarse grainy texture which was clearly regarded by the collaborators as one of their main virtues’. There was something decidedly existential about an exhibition that insisted on viewing the world as a landscape laid waste by war, decay, and disease – beneath whose ashen layers one could still find traces of life, albeing microscopic, pulsating within the ruins…the distant past and the immediate future fused into one. Thus the pavilion patio was furnished not only with an old wheel and a toy aeroplane but also with a television set. In brief, within a decayed and ravaged (i.e. bombed out) urban fabric, the ‘affluence’ of a mobile consumerism was already being envisaged, and moreover welcomed, as the life substance of a new industrial vernacular.”

Alison and Peter Smithson, Nigel Henderson, Eduoardo Paolozzi, Parallels in Life and Art. Image via the Tate Modern, 2011.

A Clash on the Horizon

The Smithsons, it is important to remember, were part of a generation both haunted by war and tantalized by the car and consumer culture of the emerging 1950s. Ideologically they were sandwiched between the twilight years of British socialism and the allure of a consumerist populism informed by fast cars and good living, and this made their work and their ideology rife with contradiction and tension.

The tension between proletarian, primitivist, anthropological elements as expressed in coarse, raw, materials and the allure of the technological utopia dreamed up by modernists a generation earlier, combined with the changing political climate of post-war Britain, resulted in a mix of idealism and post-socialist thought. This hybridized an new school appeal to a better life - made possible by technology, the emerging financial accessibility of consumer culture, the promises of easily replicable, luxurious living promised by modernist architecture - with the old-school, quintessentially British populist consideration for the anthropological complexity of urban, working class life. This is what the Smithsons alluded to when they insisted early on that Brutalism was an “ethic, not an aesthetic.”

Model of the Plan Voisin for Paris by Le Corbusier displayed at the Nouveau Esprit Pavilion (1925) via Wikipedia (CC BY-SA 4.0)

By the time the Smithsons entered the international architectural scene, their modernist forefathers were already beginning to age, becoming more stylistically flexible, nuanced, and less reliant upon the strictness and ideology of their previous dogmas. The younger generation, including the Smithsons, were, in their rose-tinted idealism, beginning to feel like the old masters were abandoning their original ethos, or, in the case of other youngsters such as the Dutch architect Aldo van Eyck, were beginning to question the validity of such concepts as the Plan Voisin, Le Corbusier’s urbanist doctrine of dense housing development surrounded by green space and accessible by the alluring future of car culture.

These youngsters were beginning to get to know each other, meeting amongst themselves at the CIAM – the International Congresses of Modern Architecture – the most important gathering of modernist architects in the world. Modern architecture as a movement was on a generational crash course that would cause an immense rift in architectural thought, practice, and history. But this is a tale for our next installment.

Like many works and ideas of young people, the nascent New Brutalism was ill-formed; still feeling for its niche beyond a mere aesthetic dominated by the honesty of building materials and a populism trying to reconcile consumerist technology and proletarian anthropology. This is where we leave our young Smithsons: riding the wave of success of their first project as a new firm, completely unaware of what is to come: the rift their New Brutalism would tear through the architectural discourse both then and now.

If you like this post, and want to see more like it, consider supporting me on Patreon!

There is a whole new slate of Patreon rewards, including: good house of the month, an exclusive Discord server, monthly livestreams, a reading group, free merch at certain tiers and more!

Not into recurring donations or bonus content? Consider the tip jar! Or, Check out the McMansion Hell Store! Proceeds from the store help protect great buildings from the wrecking ball.

#brutalism#architecture#architectural history#brutalism post#smithsons#alison and peter smithson#british architecture#modern architecture#le corbusier#concrete#brutalist architecture

933 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Turin and Lingotto: resilience, forgetting and the reinvention of place

Lingotto is a district of Turin, Italy, and the location of the Lingotto building in Via Nizza. Lingotto used to be an important industrial site and a highly symbolic space at the heart of the city of Turin, Italy.

This building once housed an automobile factory built by Fiat. Construction started in 1916 and the building opened in 1923. The design by young architect Matté Trucco was unusual in that it had five floors, with raw materials going in at the ground floor, and cars built on a line that went up through the building. Finished cars emerged at rooftop level, where there was a rooftop test track. It was the largest car factory in the world at that time. For its time, the Lingotto building was avante-garde, influential and impressive. Le Corbusier called it "one of the most impressive sights in industry", and "a guideline for town planning". 80 different models of car were produced there in its lifetime, including the Fiat Topolino of 1936.

The factory became outmoded in the 1970s and the decision was made to finally close it in 1982. The closure of the plant led to much public debate about its future, and how to recover from industrial decline in general.

Fiat asked the famous architect Renzo Piano, also the famous architect of “The Shard” in London, to give new life to this enormous building. The plan was a complete renovation of the building leaving the original structure unchanged and changing the factory into a multi-functional facility for public use.

The result was a “city in the city”. Spaces of different nature were created inside the former production spaces: from a shopping mall, exhibition spaces, hotels and offices for the service sector, to rooms for special university departments (as the automotive department of Turin’s Politecnico to the dental school) and a tropical garden. The work was completed in 1989.

The track was retained, and can still be visited today on the top floor of the shopping mall and hotel.

Lingotto may be interpreted as a mirror of Turin’s resilience strategies used to cope with the economic crises that have hit the city. This is what the Lingotto is according to Piano, “a city center outside the city centre”, a commercial place but, above all, a place promoting culture, meetings, social exchange and innovation.

**Fiat’s Lingotto factory near Turin, Italy was built in 1923 and included a rooftop test track for racing cars.

#agnelli#quote#fiat#cars#automobiles#italy#design#architrcture#renzo piano#lingutto#turin#city#urban

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vittorio Gregotti - a Master of Twentieth Century Architecture

Born in Novara on 10 August 1927, architect, urban planner and architecture theorist Vittorio Gregotti passed away on Sunday morning in Milan following the consequences of pneumonia.

Vittorio Gregotti at the Venice Biennale in Venice (1975). | Photo © Adriano Alecchi (Mondadori Publishers).

After studying under professor Ernesto Nathan Rogers he has founded his studio Gregotti Associati in 1974. Theorist and professor at the Politecnico di Milano received the gold medal for his career at the Triennale di Milano in 2012. With more than 60 years of professional practice as an architect he was as well a director of the Casabella between 1981 and 1996.

Italian edition of Casabella Magazine nº264. | Photo via Metalocus

“The Invention of Territory”. | Photos © Vittorio Gregotti, Centre Pompidou

“Gregotti was once described by Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas as an Italian communist architect who wanted to build dams all over the world,” writes Bart Lootsma in his essay The strategies of OMA published in Forum 3 (1985).

He remembers Gregotti while writing his beautiful memory on Facebook “Gregotti's architecture seemed incredibly rigid and sometimes even severe, with its repetitive facades. He was an incredibly nice and charming man though. I will never forget how he defended his design for the centennial le Corbusier exhibition in 1986 in the Centre Pompidou, which was curated by Bruno Reichlin. The enormous undertaking was also possible because Jean Louis Cohen was one of the first to have a small Apple Macintosh computer, in which every little piece exhibited was archived. Gregotti had laid out he complete top floor with crosses of walls, all equal in size. So what would normally be a closed wall with maybe a door in it, now consisted of two walls with an empty space in between. There were four of those in every space. Of course, every curator who did a part or parts of the show (I did the piece on the Poeme Electronique and a slide show on the Synthese des Arts) demanded a special design for his or her contribution and they all had good reasons. Gregotti patiently explained to each and every one of them that actually it was completely possible to realise all their demands in his structure. They all accepted, and there were some very good architects and architectural historians among the curators that would normally get their way. I was very impressed. Gregotti was quite an intellectual as well, leaving many essays and books. But I learned to know him in the Centre Pompidou as simply a humble, charming and wise man and architect.”

youtube

Biennale Architectura : Vittorio Gregotti | Sorry, only available in Italian.

Meanwhile, also other memories, like from Pierfrancesco Maran, the Councilor for Urban Planning of the Municipality of Milan were published “in these difficult days dead often become numbers and statistics, while it can cause pain for many families and losses for the whole community. Among them is also Vittorio Gregotti, a great architect who has left many marks in Milan and has unfortunately become the coronavirus victim."

youtube

Una lezione di architettura : Vittorio Gregotti | Sorry, only available in Italian.

Luigi Prestinenza Puglisi, an architectural critic and a professor of contemporary architectural history at the La Sapienza University in Rome shares his thoughts that "I have always considered Gregotti an opponent and it would be wrong to change judgment only because he disappeared. However, the world without those who think differently from you is smaller and less interesting, certainly poorer.”

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Le Corbusier Architect: Corb Architecture

Le Corbusier, Architect, Modern Building, Photo, Houses, Projects, Studio, Pictures, Designs

Le Corbusier Architect : Architecture

20th Century Architecture – French Modernism: Buildings by Charles Edouard Jeanneret

Le Corbusier Architect News

15 Nov 2020

Cité Radieuse

Italian independent artist Stefano Meneghetti from Venice, Italy, just finished an unreleased “Radieuse” Tech EP.

Stefano Meneghetti with his team, makes the album Cité Radieuse & Cité Radieuse RE:RE:MIX as a tribute to the admired Le Corbusier, innovative architect and urban designer, who built in Marseille a model of urban planning designed for its inhabitants to live harmonious relationships.

The songs were composed by Stefano Meneghetti who brought musicians of the calibre of Giuseppe Azzarelli, Massimiliano Donninelli, Yannick da Re and Cristian Inzerillo to work together with him.

Deeply interested in architecture, music, and design, Stefano Meneghetti and his friends wanted to name this album La Citè Radieuse out of admiration for Le Corbusier, the legendary Corb, multifaceted and innovative architect, designer and urban planner, who created his city-like housing project in Marseille with the aim of fostering harmonious relationships among its inhabitants.

Sound research and experimentation are the focal points of this musical partnership. The album develops an architecture of electronic sounds, which incorporates eclectic influences.

Stefano Meneghetti, graphic artist and video maker, is a long-standing collaborator of musicians such as Gary Numan, Franco Battiato, Byetone, Lorenzo Palmeri and many others.

As Giuseppe Azzarelli says: “A city is not only an environment of spaces and forms. Inevitably, it also expresses its dimension through sounds: every environment has its own acoustic imprint reflecting human activities, their relationships with the world and with each other. The idea of a Cité Radiuese, ideal and utopian city within a city, conceived by Le Corbusier for people and their needs, immediately enthralled me by its “humanity”, drawing me closer to a world of sound that can underline or accentuate possible emotional meeting points in the multifaceted reality of the modern city.”

youtube

Interview with Stefano Meneghetti:

“Music has helped me build parallel worlds; through this reciprocity with music I have created scenarios and stories, experiencing the world without being part of it, as if I lived observing it from a car (train?) window, through binoculars or a microscope.”

“Over the course of my life, I have felt a natural affinity for certain musical textures as well as personalities: from Gustav Mahler to Brian Eno, Alva Noto to Franco Battiato, and Teho Teardo & Blixa Bargeld to Georges Ivanovic Gurdjieff.”

“With his Cité Radieuse Charles-Edoard Jeanneret-Gris, better known as Le Corbusier, was simply the gravitational field where everything started.”

“The inhabitants of the same building live just a few centimetres away from each other, separated by a simple partition wall, and share the same spaces whose pattern is repeated on each floor. They do the same things at the same time: turn on the tap, switch on the light, set the table, a few dozen synchronized lives which are repeated on floor after floor, from one building after another, from one street to the next.”

“Like an anthropologist or an archeologist, I wandered discreetly around the Unité d’Habitation de Marseille to observe the lives of individuals, families and groups which are still unfolding in the radiant city.”

From the EP

Cité Radieuse Youtube channel

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCF2F1StpGAzbXeW97J4LSUA

Stefano Meneghetti / Music Producer

[email protected]

21 Sep 2020

Le Corbusier’s early drawings. 1902-1916

Curated by Danièle Pauly

Dates: September 19, 2020 – January 24, 2021

Location: Teatro dell’architettura Mendrisio, 6850 Mendrisio, Switzerland

Phone: +41 58 666 50 00

Exhibition promoted by

Fondazione Teatro dell’architettura

With the collaboration of the Accademia di architettura – Università della Svizzera italiana

Le Corbusier’s early drawings. 1902-1916

18 Nov 2017

Villa Le Lac, Corseaux, Switzerland

An abstract impression of the wall of Villa Le Lac by Le Corbusier (Route de Lavaux 21, CH-1802 Corseaux, Vevey, Switzerland)

Le Lac by Jan Theuninck, acrylic on canvas, 70 x 100 cm, 2017

image courtesy of Jan Theuninck

Jan Theuninck met Albert Jeanneret, the brother of Le Corbusier, who lived in the villa until 1973, in the village of Finhaut around 1970. Albert Jeanneret was a musician, composer and violinist. He helped developing the Dalcroze Method in Hellerau, Germany.

The Dalcroze Method or simply eurhythmics, is one of several developmental approaches including the Kodály Method, Orff Schulwerk and Suzuki Method used to teach music to students. When Theuninck met him, he was experimenting with sound recordings of daily life noises which he called “bruits humanisés”.

1 Sep 2017

Pavillon de l’Esprit Nouveau in Bologna

The restyling of the Esprit Nouveau Pavilion in Piazza Costituzione in Bologna has started and is due to complete in October 2018.

The building will be cleaned and painted, with replacement of the windows and refurbishment of the awnings and the access path, report www.platform-ad.com.

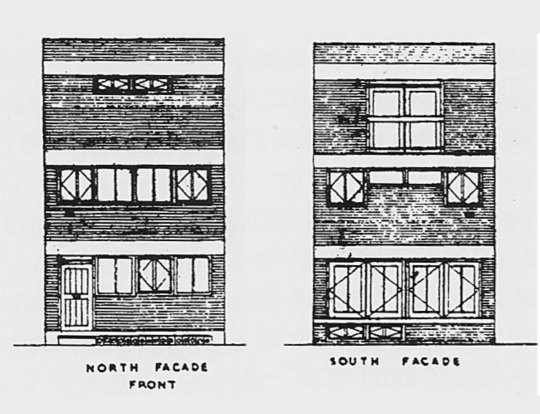

The Esprit Nouveau Pavilion consists of two parts:

– “cell-unit” of the “Immeubles Villas” housing project

– Diorama: a “roundabout” for the exhibition of projects and theoretical statements

Designed separately in 1922, the two sections were combined and integrated in 1925 at the international exhibition of Decorative Arts held in the park around the Gran Palais in Paris.

This building was constructed in 1977. Construction of the replica was based on period documents and photographs.

source: https://ift.tt/35xLqst

20 Jul 2016

Le Corbusier Buildings Added On UNESCO World Heritage List

Istanbul, Turkey, 17 July — The World Heritage Committee this morning inscribed four new sites on the World Heritage List: the transnational serial site of The Architectural Work of Le Corbusier, an Outstanding Contribution to the Modern Movement (Argentina, Belgium, France, Germany, India, Japan, Switzerland), along with sites in Antigua and Barbuda, Brazil and India.

The Architectural Work of Le Corbusier, an Outstanding Contribution to the Modern Movement (Argentina, Belgium, France, Germany, India, Japan, Switzerland) – the 17 sites comprising this transnational serial property are spread over seven countries and are a testimonial to the invention of a new architectural language that made a break with the past. They were built over a period of a half-century, in the course of what the architect described as “patient research”.

The Complexe du Capitole in Chandigarh (India), the National Museum of Western Art, Tokyo (Japan), the House of Dr Curutchet in La Plata (Argentina) and the Unité d’habitation in Marseille (France) reflect the solutions that the Modern Movement sought to apply during the 20thcentury to the challenges of inventing new architectural techniques to respond to the needs of society.

These masterpieces of creative genius also attest to the internationalization of architectural practice across the planet.

The Curutchet House, La Plata, Argentina, is not very well known compared to the other three metnioned above. It was commissioned by Dr. Pedro Domingo Curutchet, a surgeon, in 1948 and included a small medical office on the ground floor. The house consists of four main levels with a courtyard between the house and the clinic. The building faces the Paseo del Bosque park. The main facade incorporates a brise soleil. Construction began in 1949 under the supervision of Amancio Williams and was completed in 1953.

Website: Le Corbusier Buildings on UNESCO World Heritage List

Loving Le Corbusier

3 Jun 2016 – A new novel ‘Loving Le Corbusier’, tells the story of Yvonne, the wife of architect Le Corbusier.

In doing so, it naturally references many of Corb’s buildings as well as gives great details on France in the first half of the twentieth century.

Book cover:

‘When I visited Le Corbusier’s apartment in Paris I was surprised to find that there was not a single photograph of his wife. In most books she was mentioned only in passing as a model. I wanted to know more.’

Unité d’Habitation, Marseille, Southern France, celebrated work by Corb:

photo from Colin Bisset

This publication is a tale of love and loss set against the great events of 20th century Europe.

Villa Savoie scanned photo © Isabelle Lomholt

The book follows the life of the young woman from Monaco who captured the heart of a man who became one of the most influential and divisive architects of the twentieth century. Spanning the period from the end of the Great War to the Riviera chic of the 1950s, Yvonne witnessed the fun of the Jazz Age and the desperate loneliness and displacement of Occupied France in World War Two.

Yvonne, the architect’s wife:

photograph © Fondation Le Corbusier

The novel is peopled by some of the most creative characters of the century, and set in France’s most stunning locations, from Paris in its Art Deco heyday to the glittering sunlight of the Côte d’Azur. As Corb’s fame grows, so, too, does the distance between him and his wife. This is a portrait of a love affair that defies the odds, and of a country in flux.

The architect’s grave – designed by himself – in the south of France:

photo from author Colin Bisset

Colin Bisset was born in the UK but now lives in Australia. He is a regular architectural and design commentator for ABC Radio National (Australian Broadcasting Corporation). He has a degree in History of Art, specialising in modern architecture, and he is the author of the novel ‘Not Always To Plan’ (Momentum/ Pan Macmillan).

Chapel of Notre Dame du Haut in Ronchamp, France:

photograph from Colin Bisset

Website: Loving Le Corbusier Book

Colin’s novel is available on Amazon, iTunes, Kobo and other e-retailers.

6 Apr 2016

Cité de Refuge, 12 Rue Cantagrel, 75013 Paris, France

photo by Rory Hyde

Cité de Refuge Building in Paris

30 Mar 2016

Corb Tapestry at Sydney Opera House, New South Wales, Australia

photo from www.smh.com.au

Sydney Opera House – Le Corbusier tapestry titled ‘Les Dés Sont Jetés’ (‘The Dice Are Cast’), commissioned by Jørn Utzon.

The building is of course a masterpiece of 20th Century architecture that is admired internationally and treasured by the people of Australia.

Latest Le Corbusier Buildings added

Pavillon Philips, Exposition Universelle de Bruxelles, Belgium – added 14 May 2013

Date built: 1958

Design: with Iannis Xenakis

photograph © Archive famille Xenakis

Iannis Xenakis was a Greek-French composer, music theorist, and architect-engineer. After 1947, he fled Greece, becoming a naturalized citizen of France.

Villa La Roche, Paris, France – added 12 Jun 2011

Date built: 1925

Design: with Pierre Jeanneret

photograph © Karavan

Villa La Roche

Key Le Corbusier Project

Featured House by Corb

Villa Savoie, Poissy, north west of Paris, France

Date built: 1929

building image © Karavan

Villa Savoie – key Modern French building

This famous Modern house demonstrates the ‘Five Points’ that Corb placed central to his work: these are piloti, fenetre longeur, free plan, active roof space and the free facade.

photo © Victor Gubbins

Villa Savoye : photos of this famous Le Corbusier house as a ruin.

11 Feb 2012 Le Corbusier News – Cité Radieuse Fire

On Thursday evening, three apartments (eight apartments noted in one report) in the Cité Radieuse were destroyed in a fire and around 35 others were seriously damaged. The Cité Radieuse is located in Marseilles, France.

The nine storey housing block was designed by Corbusier and completed in 1951/52. The cause of the fire is still unknown.

The Radiant City building was classified as a historic monument in 1995.

Cité Radieuse – report in The Guardian : external link

Le Corbusier Exhibition

Le Corbusier Show : The Interior of the Cabanon

interior photo : Andrea Ferrari

Le Corbusier Exhibition : RIBA, London

A reconstruction of Corb’s beach hut Cabanon, which is designed and built in 1952 for his holidays at Cap-Martin. The Cabanon design by Corb is a 15 square metre ‘pied a terre’ made of rustic wood in 1952 and the only structure ever built for his own use.

Key Buildings by this Architect in Paris

Maison Ozenfant / Ozenfant House & Studio

–

Date built: 1922

Pavilion L’Esprit Nouveau / L’Esprit Nouveau Pavilion

–

Date built: 1925

Pavilion Suisse / Swiss Pavilion

Cité Universitaire

Dates built: 1931-32

Cité de Refuge, Paris

Date built: 1933

Weekend House

–

Paris project

Plan Voisin for Paris

Date built: 1925

Le Corbusier buildings close to Paris

Villa Savoie, Poissy, north west of Paris

Date built: 1929

Villa Stein, Garches

Date built: 1927

Maisons Jaoul, Neuilly-sur-Seine, Paris

Dates built: 1954-56

RIBA Gold Medal Winner 1953

Le Corbusier’s real name is Charles-Edouard Jeanneret-Gris. He worked as an architect in Paris from 1917. Popularily known as Corb by architects.

Corbusier Buildings not in the Paris area

Unité d’Habitation, Marseille, France 1952

Chapel of Notre Dame du Haut, Ronchamp, France 1955

La Tourette Monastery, Lyon, France 1957

Unité d’Habitation, Berlin, Germany 1959

Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts, Cambridge, USA 1963

Pessac housing, Bordeaux, France 1926

Centrosoyuz, Moscow, Russia 1936

Unité d’Habitation, Berlin

scanned photo © Isabelle Lomholt

German Unité d’Habitation Berlin Le Corbusier building

American Le Corbusier building – UN Building New York

More Corb Architecture projects online soon

Posthumous Le Corbusier building

Saint-Pierre church, Firminy, France

Date: 2007

Other Le Corbusier Buildings

Villa Le Lac, Corseaux, Vevey, France 1924

Villa La Roche, Paris, France 1925

Villa Jeanneret, Paris, France 1925

Maison Planeix, Paris, France 1928

Maison Clarté, Geneva, Switzerland 1932

Casa Curutchet, La Plata, Argentina 1954

National Museum of Western Art, Tokyo 1959

Heidi Weber Pavilion, Zurich, Switzerland 1965

Espace Corbusier, Firminy, France 1967

Chandigarh – various buildings, India

The Heidi Weber Pavilion forms the Centre Le Corbusier

Villa Savoie, France – classic Modern building that features in many world histories of architecture

building image © Isabelle Lomholt

Location: 35 rue de Sèvres, Paris, France

Le Corbusier Paris – Practice Information

Former architect studio based in Paris, France – world-famous Modernist architect

Corb had his architect studio at 35 rue de Sèvres from 1922 with his cousin Pierre Jeanneret.

Paris Architects : Parisian Architecture Studios

French Buildings

Modern Architecture

Modern Architects

Modern Houses

Famous 20th Century architecture by architects such as Philip Johnson, Frank Lloyd Wright, Alvar Aalto, Eero Saarinen, Mies van der Rohe, Adolf Loos and Antoni Gaudí.

Homes featured include the Farnsworth House, USA; Arango Residence, Acapulco ; Tugendhat Villa, Brno; and Casa Mila, Barcelona.

Paris Architecture

Architecture Studios

Buildings / photos for the Le Corbusier Paris Architecture – French Modernist Architect page welcome

Website: Fondation Le Corbusier, Paris

The post Le Corbusier Architect: Corb Architecture appeared first on e-architect.

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

In the United States, the major flashpoint is brutalism, a post-war style that marries imposing concrete-and-steel design with stripped-down functionalism. Left-wingers darkly warn of the alt-right “infiltrating” architecture twitter under the guise of criticizing brutalist buildings. Others defend brutalism as a symbol of our lapsed commitment to public housing and economic justice.

Though brutalism is defended on both aesthetic and political grounds, the two arguments are difficult to reconcile. To a certain type of critic, brutalism represents “heroic architecture,” the realization of an individual designer’s vision in concrete and steel. Mid-century pioneers of brutalism like Le Corbusier and Ernő Goldfinger were minor celebrities. Le Corbusier’s architectural vision was uncompromisingly individualistic, unmoored from tradition or conventional ideas about form and beauty. It is no accident that Howard Roark, the fictional protagonist of Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead, was also an iconoclastic architect. (Roark’s aesthetic sensibilities were closer to Frank Lloyd Wright than Le Corbusier, and the Swiss architect probably would have bridled at Roark’s politics, but the parallels between the two are unmissable.)

To a few intellectuals, brutalist buildings are heroic achievements, but the public has never warmed to them. When Naples’ notorious Gomorrah housing project was recently torn down, the loudest naysayers were professional architects. Actual residents had long complained about the buildings’ conditions. But if you’re not willing to defend the aesthetics of brutalism, ideology will suffice. So says today’s leftist journal Jacobin, trumpeting “Save Our Brutalism,” and lauding the great mid-century brutalist buildings as potent symbols of our now-forgotten commitment to equality.

Defending brutalist buildings on ideological grounds only highlights the divide between design and the lived experience of a building’s residents. As James C. Scott points out in Seeing Like a State, there is a profound gulf between the God’s-eye view of architects and policy-makers and the ground-level view of actual inhabitants, who have to live with brutalism’s unforgiving sterility. From the air or from a distance, Oscar Niemeyer’s vision of Brasilia is a striking achievement. To the city’s inhabitants, however, the Le Corbusier-inspired design is artificial and alienating. Brutalism proposed to strip buildings down to their barest functions, yet it fails at the basic task of providing a welcoming, visually-appealing space for residents and passers-by.

Ascribing a single ideological message to a diffuse architectural movement is also mistaken. Perhaps Jacobin subscribers equate brutalism with public housing, but the meaning is more sinister in Eastern Europe. The tiered design of the Gomorrah housing projects bears a marked resemblance to the resorts built for Communist apparatchiks on the shores of the Baltic Sea. Your average Latvian is more likely to associate these buildings with Soviet-era repression and mismanagement than left-wing nostrums about equality. Enver Hoxha’s Albania produced some striking examples of brutalist architecture. Hoxha, not coincidentally, was a notorious tyrant.

Design fads come and go and political sensibilities change, but the technocratic, top-down worldview that undergirds brutalism persists. In 2011, the Dutch celebrity architect Rem Koolhass was quite open about his preference for “the generic city” over architecture rooted in local culture or history:

The traditional city is very much occupied by rules and codes of behavior. But the generic city is free of established patterns and expectations. These are cities that make no demands and, consequently, create freedom. Some 80 percent of the population of a city like Dubai consists of immigrants, while in Amsterdam it is 40 percent. I believe that it’s easier for these demographic groups to walk through Dubai, Singapore or HafenCity than through beautiful medieval city centers. For these people, (the latter) exude nothing but exclusion and rejection. In an age of mass immigration, a mass similarity of cities might just be inevitable. These cities function like airports in which the same shops are always in the same places. Everything is defined by function, and nothing by history. This can also be liberating.

Technocrats once spoke the language of socialism and central planning; Koolhass and his ilk are more likely invoke markets, openness, and globalization. But the underlying impulse is the same: Society can be cataloged, organized, and ultimately shaped from the top down through the design of its cities and buildings. Beauty, tradition, and culture are secondary considerations.

Even if we dismiss brutalism as a fad perpetrated by blinkered technocrats and egotistical architects, ugly buildings expose ugly truths. Pervasive ugliness seems to impose an unconscious psychic tax on the great mass of people, even if most have no interest in the finer points of architecture or design. So why have we lost the ability to construct beautiful buildings? There are no easy ideological answers. Socialism may have birthed brutalism, but capitalism has given us barren strip malls, cookie-cutter exurbs, and Koolhaas’s “generic city.”

By contrast, Notre Dame de Paris was a communal undertaking, built by generations of craftsmen and artisans. The names of several of its earliest architects are lost to history. Crude historical revivalism is also unsatisfying. Warsaw’s ersatz Old Town, rebuilt in the wake of World War II, is an impressive testament to Polish national will, but it lacks the authentic charm of Krakow’s beautifully-preserved historic district. Budapest’s Fisherman’s Bastion, a restored medieval structure, pales in comparison to the city’s old baroque neighborhoods. And Huawei’s “European” campus, plopped down in the middle of Southern China, is the architectural equivalent of the uncanny valley: The closer it hews to historic European buildings, the faker it looks and feels.

171 notes

·

View notes

Photo

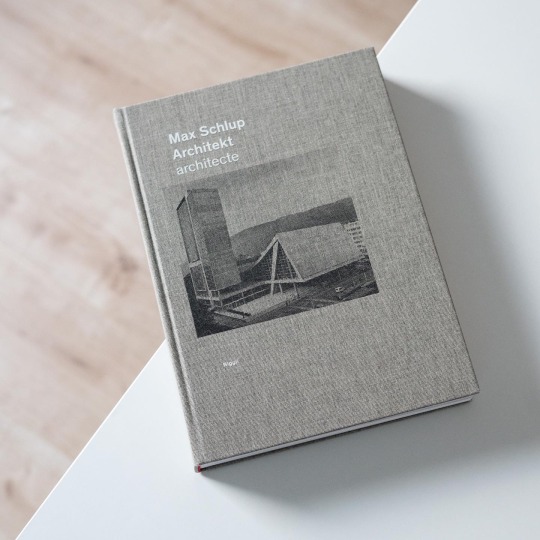

Within the rich Swiss postwar architectural history the Solothurn School, indelibly marked by the architects Fritz Haller, Franz Füeg, Max Schlup, Alfons Barth and Hans Zaugg, takes on a somewhat unusual role: rather than following the example of Le Corbusier and taking on a sculptural, brutalist idiom the architects leaned towards the glass and steel architecture of Mies van der Rohe. Among the five protagonists Max Schlup (1917-2013), based in the city of Biel, stands out as the most poetic yet daring architect whose major works include Miesian buildings like the Strandboden secondary school or the Mother-Child-Facility in Biel just as well as the Biel Congress Center with its large concrete surfaces and a scooped roof construction. The latter likely is a result of Schlup's excursion to Brasilia where he admired the immense construction activities and the spirited architecture of Oscar Niemeyer. In 2013 the Architekturforum Biel published the monograph "Max Schlup - Architekt/architecte" with Niggli, a beautifully designed homage to the city's most significant postwar architect. The book focuses on a selection of ten buildings, including the previously mentioned school and congress center, each of them presented in old and new photographs, plans and brief texts. This somewhat narrow focus is a bit disappointing since the work catalogue included in the back of the book counts about 100 projects. Accordingly the reader only receives a partial impression of Max Schlup's work that nonetheless manages to bring across the poetry and charme of his buildings that through extensive glazing frame the surroundings in a beautiful way. Beyond that four essays by Jürg Graser (THE expert on the Solothurn School), Martin Tschanz, Christian Penzel & Christoph Schläppi each discuss one building, shed light on their construction, materiality and try to uncover inspirational sources, a speculative dimension of Schlup's work that also a long interview with the architect cannot dissolve.

The little flaws notwithstanding "Max Schlup - Architekt/Architecte" is a beautiful and necessary book about a key Swiss architect that really is a feast for the eye.

#max schlup#solothurn school#architecture book#swiss architecture#architecture#switzerland#monograph#book

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Architecture and the Sculpture Effect of Natural Light

Abstract

Visual form depends upon three variables: light, the position of the beholder, and the particular relation with the environment. We empirically reinterpret the image into an idea of corporeality, and this defines the form of the space within. We thus grasp its spiritual import, its content, and its meaning. Windows form the rhythmical articulation of light and dark in the façade, which determines the character more directly than the sum total of all columns, ornaments and cornices. To see architecture means to draw together into a single mental image the series of these dimensionally interpreted images that are present to us as we walk through interior spaces and round their exterior shells. It is light that first rounds out mathematical precision and space consciousness to the freedom, independence and law of architectonic creation.

Keywords: natural light, stimulus, visual attention, primary form, plastic effect, beauty

Introduction

We look at what we want or need to see, unless our visual attention is redirected by the focus selector to a distracting stimulus in the visual field. Such a stimulus need not be the brightest thing in view. The information content of the stimulus is also important in determining its relevance and consequently its inherent attractiveness to the mind’s eye. Visual activity is highest in a very small area of the retina called the fovea. Under normal conditions patterns of light falling on the fovea are reported to the brain in much finer detail than the visual information falling on other parts of the retina. This innate differentiation between central and peripheral vision. High luminous (brightness) of the background tends to dominate the visual field causing the eye to reduce the amount of light which it lets fall onto the retina, thus interfering with the perception of the person. When lightly illuminated elements of the visual field are unrelated to our needs. They distract us from our conscious activities which can be both annoying and dangerous. Recent research on the visual cortex of the brain shows that the brain sees most clearly in terms of edges.

Le Corbusier deliberately defined architecture not in Vitruvian terms as good planning, sound construction and pleasing appearance, but in terms of the sculptured effects of light and shade, in the masterly correct and magnificent play of masses brought together by light. Our eyes are made to see forms in light; thus cubes, cones, spheres, cylinders or pyramids are the great primary forms which light reveals to advantage. They are not only beautiful forms, but the most beautiful. Before 1750 it was well known that the Greeks had made their windows narrower at the top than at the bottom. This arrangement could be seen in such Roman ruins as the round temple at Tivoli. The Greek fanatics did not use windows at all but admitted light through the doors of their temple. To them, light meant brightness which had to impress. The impressionists realized the importance of ambient light, which fills the air and is reflected from objects, and radiant light, which is the province of the physicist. Monet’s paintings of the cathedral at Rouen, all depicting the same façade but under different conditions of light are as explicit an illustration of the role of ambient light in vision as one could expect to find.

Throughout history designers have attempted to introduce light in a way that the observer will be conscious of the effect of the light while the light source itself is played down in the architecture composition. For example, windows were placed at the base of a dome to light this large structural element. The brilliant dome then became a major focal center and serving as a huge reflector. The dome, not the windows, became the apparent primary light source for the interior space. Similarly, the windows in some interiors were placed so they were somewhat concealed from the normal view of the observer and the observer’s attention was focused on a brightly lighted adjacent decorative wall. In both cases, the objective was to place the emphasis on the surfaces to be lighted while minimizing any distracting influence from the lighting system itself.

For medieval thinkers, light is the principle of order and value. The objective value of a thing is determined by the degree to which it participates in light. Seeing is not a passive response of the pattern of light, rather it is an active information seeking process directed and interpreted by the brain. Visual sensory data are coordinated with incoming contextual information from the other senses related to the past experiences of a comparable nature and given attention or not depending on whether incoming stimulus is classified as signal or noise. It is the information content and context of a stimulus not its absolute magnitude which generally determines its relevance and finally its importance. This in turn largely determines what we look at and what we perceive. The eye searches the visual environment automatically for signals which supply information relevant to the satisfaction of activity or biological needs, and figure objects with these characteristics tend to attract the visual attention automatically.

Light in Gothic Architecture

For the 12th and 13th centuries, light was the source and essence of all visual beauty. St. Victor and Thomas Aquinas both ascribe to the beautiful two main characteristics: consonance of parts, or proportion, and luminosity. The stars gold and precious stones are called beautiful because of the quality. In the philosophical literature of the terms no attribute is used more frequently to describe visual beauty than lucid, luminous, clear. This aesthetic preference is vividly reflected in the decorative arts of the time with their obvious delight in glittering objects, shiny materials and polished surfaces. According to the Platonizing metaphysis of the Middle Ages, light is the most mobile of natural phenomena, the least material, the closest approximation to pure form. Light is the mediator between bodies and bodily substances, a spiritual body, embodied and is present in the earthly substances. For as St. Bonaventure asks, do not metals and precious stones begin to shine when we polish them, are not clear window panes manufactured from sand and ashes, is not fire struck from black coal, and is not this luminous quality of things evidence of existence of light in them. In architecture history, the large stained-glass windows of the Gothic period are probably the most obvious example of this approach.

Early Gothic structure was of course closely related to the question of space, light, and plastic effects in the Gothic period we learn about. In Amiens we are not forcibly pulled to the east as is the case in Baroque churches, since the lighting is evenly diffused from one end to the other. The sanctuary is backed by an ambulatory which is lighted by the window of the radiating chapels that are barely visible from the west. In Cathedral Le Mans France, the clerestory lighting the inner aisle and the light pouring in from the side chapels all combine to produce a lavish yet organized richness which every part is necessary for either function or structural reason. The Gothic light is filtered through the pores of the walls. The stained-glass windows of the Gothic replace the brightly colored walls of Romanesque architecture. They are structurally and aesthetically not openings in the wall to admit light, but transparent walls. The stained-glass windows seemingly deny the impenetrable nature of matter, receiving its visual existence from an energy that transcends it. Light which is ordinarily concealed by matter appears as the active principle and matter is aesthetically real only in so far as it partakes of and is defined by the luminous quality of light.

The Gothic may be described as transparent diaphanous architecture. The gradual enlargement of the windows as such means that no segment of inner space was allowed to remain in darkness undefined by light. The side aisles, the galleries above them, the ambulatory and chapels of the choir became narrower and shallower, their exterior walls pierced by continuous rows of windows. Ultimately, they appear as a shallow, transparent shell surrounding nave and choir, while the windows if seen from the inside cease to be distinct. They seem to merge, vertically, and horizontally into a continuous sphere of light, a luminous foil behind the tactile forms of the architecture system. The window opening is a void surrounded by heavy, solid framing. In the Gothic window, the solid elements of the tracery float, as it were, on the luminous window surface, its pattern dramatically articulated by light.

The Window

Natural light projects natural shade. The perception of form occurs through the variation in brightness and darkness. Time in the aesthetics of architecture is the parameter which refers to the duration of the aesthetical experience, and as a consequence of that duration to the bodily movement of the beholder, who takes successively different standpoints around and through the object observed. Visual form is controlled by the polarity of one image-like perception. When the beholder is forced to take different standpoints to grasp the whole, the visual form is a result of many images. Visual form depends upon three variables: light, the position of the beholder, and the particular relation with the environment. We empirically reinterpret the image into an idea of corporeality, and this defines the form of the space within. We thus grasp its spiritual import, its content, and its meaning. From whatever side we take light we ought to make an opening for it, as it may always give us a free sight of the sky. The top of that opening ought not to be too low, because we are able to see the light with our eyes.

Windows form the rhythmical articulation of light and dark in the façade, which determines the character more directly than the sum total of all columns, ornaments and cornices when seen from a distance. All decorative forms sink back into the mass of reflecting wall and the dark fleck of the windows which reflect no light. On the inside neither paint, wall, ceiling nor door can match the window. It stands among them like something alive among dead things and has within it the power to make the room large or small. The window is employed exclusively as a part of the façade, as if it is consisted of a kind of embellishment similar to columns or woodwork. It no longer has the shape or size which the room requires to illuminate it, but rather must attune itself to the rhythm of the façade. It is no longer positioned where it is needed in the room, but rather where it is needed in the façade.

We must not strive to increase the intensity of light, but a gentler light is worth striving for, and more colored light must be the watchword. The living quality of architecture depends upon sensuous seizure by means of touch and sight, upon the terrestrial cohesion of mass, upon the super-terrestrial liberty of light. It is light that first gives movement to mass and sublimates it to a super sensuous expression of dynamic and rhythmical agitation. It is light that first rounds out mathematical precision and space consciousness to the freedom, independence and law of architectonic creation. The outer walls collect light in order to let it penetrate fully through its openings. However, a traditional wall pierced with windows almost belongs to a past period. The transparent or opaque screen fitted between floor and ceiling is taking its place. To see architecture means to draw together into a single mental image the series of these dimensionally interpreted images that are present to us as we walk through interior spaces and round their exterior shells.

Architecture Image

Architecture image is one unified mental image. The intensity of light must be as uniform as possible throughout the interior. Throughout the exterior, gradation of light when present are subtle. There is no sharp contrast and the darker areas are always bright enough to allow clear vision. Colors bring the structure lines into a sharp relief against the seeming wall. Strong bright reflections are avoided even when the material is bronze or gold. Painted colors spread as uniform surfaces. The color detaches ornament from its frame and separates a capital from its shafts. The colors are set down separately in small areas. Architecture image is determined as we walk through the building. The architecture image is unique. It is always the same no matter whether it is seen from many different angles. It is identical with the actual complete form. There is not temptation for us to walk around the building because we realize at once that it can offer us no surprise. Coordination of the individual images and simplicity of the total image, these are architecture produced in the interior by radiating lines of circulation. We can stand anywhere and yet feel ourselves in possession of the whole. The architecture of the first phase presents only one image. The second phase is contrast. Uniformity of illumination gives way to increasing contrast of light and dark areas. The introduction of lunettes is a result of the need of light on the vault. The need increases for a ceiling that is bright, unfolding a zone of light rather than a dark enclosure. It is a symptom of the second phase that skylights were considered for the ceiling.

The distinction here does not lie in a different degree of intensity of light but solidity in the way light is disrupted. Such sudden transition from bright to dark to bright are also characteristic of the individual details. The uneven illumination subordinates the vague isolated vistas to those that are clear, the optically dull, the optically interesting. The corporeal forms exist only to carry the visible phenomena. They serve light not the reverse. They appear to suffer under the influence of light and shadow reflections and colors, and the distractions of the perspective view insofar as they might be separated, and they appear to be torn apart insofar as they belong together. Masses and spaces are pushed into one another, and since they always seem to be incomplete, we cannot imagine how they would be perceived from another viewpoint.

Baroque Architecture

In Bernini’s sculpture the problem of light and therefore the distribution of plastic surfaces in terms of their values as reflection of light, was from the very beginning one of his principal preoccupations. An architecture expression of the investigation of luminous values can be seen very clearly in the profiles of the base of his Apollo and Daphne and in the altar aedicula of Santa Bibiana. It is in fact from scenography that Bernini derived his effects of a closeup hidden light that makes the surfaces of his subject and that in the Baroque era was indeed defined as “Luce alla Bernina. With the memorial inscription for Urban VIII on the internal façade of Santa Maria in Aracoeli and the apse of San Lorenzo in Damaso, his use of light became revolutionary. Instead of hiding its source behind a screen, it takes its place in the visual field of the spectator. This direct incident light is used as an essential ingredient of the architectonic design. It is not adopted merely to enliven flat diagrams as were the diaphanous surfaces of stained glass in Gothic cathedrals, but rather its function is the integration of a plastic discourse. This progressive sensibility to the problems of light in architectonic terms can be traced from its first pronouncement in the altar of Santa Bibiana.

In Boromini’s work the perspective colonnade constructed in the Pallazzio Spada proved that through the geometric curves, space can be molded as a resextensa contracting and dilating it; on the other hand to rest his control over light in its function as determining factor of the effect of depth as shown in the series of embrasures originally opened in the structure to admit a direct lateral illumination through the perspective treatment of splayed openings, a theme introduced in Rome by Sangallo in the courtyard of Palazzo Farnese. The sensitizing of the mass in terms of its role as either reflection or obstruction of the light flow radically transforms the dynamics of the relationship and leads to an absolute plastic continuity of the architectonic members to a rigorously logical connection of the elements clarified in every point with insistent precision.

Conclusion

Louis Kahn said that every space intended to be dark should have just enough light from some mysterious opening to tell us how dark it really is. Each space must be defined by its structure and the character of its natural light. The structure is synonymous with the light which gives image to the space. The glare is modified by the lighted wall and the view is not shut off.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

. Location | Stuyvesant Town, New York, USA Le Corbusier has described New York as a city “utterly devoid of harmony.” He wasn’t impressed by the tall towers, and stated that they were a product of an inferiority complex. He believed the city would do better by building buildings that don't outdo each other, and which were more or less identical. Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper Village, also known as Stuy Town, was planned in 1942 as a post-war affordable housing project for war veterans and is an early example of a towers in a park design in New York. The idea of the design was to create a country within a city, and was created by Robert Moses. The design has moreover resemblance to Le Corbusier's Radiant City; separating pedestrians from cars and commercial spaces. The town contains 110 cruciform-like buildings with 11,250 apartments. Only 25% of the area is occupied by the 110 buildings, while the rest is open space. (at Stuyvesant, New York)

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Exploring the Vibrant Charms of Chandigarh: A 3/4-Day Itinerary with Bike Rental

Chandigarh, the capital city of both Punjab and Haryana, is a well-planned and modern metropolis that seamlessly blends urban development with natural beauty. Chandigarh has a wide range of attractions for any traveller with its broad, tree-lined boulevards, beautiful gardens, and architectural wonders.