#Laugharne

Text

Dylan Thomas had an ideal vantage point to inspire his writing

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Whenever I rewatch The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel episode with Rufus Sewell in it, I’m instantly but unconsciously reminded of my great grandmother knowing poet Dylan Thomas.

So, Rufus spent some of his early life living in a converted pub, which was at one point a pub favoured by Thomas. This was in the small town of Laugharne in Carmarthenshire, Wales, a place known as the home of Dylan Thomas’ famous boathouse.

The Boathouse along the Taf estuary.

Anyway, seeing him on the show, I’m reminded of the fact that my great-grandmother knew Dylan Thomas at one point.

She lived about 10 miles away, in the same house she was born in and would later die in.

Somehow, they knew each other.

My great-grandmother with my gran (left) and my great-grandmother with me as a baby (right).

At some point in time, their paths crossed in Laugharne but unfortunately it did not go well. As she was who she was, no one knows exactly what happened or was said, as she was a very private woman but she did tell people, that she thought he was, cach (which is basically welsh for shit).

I’m aware I don’t know the great details of their acquaintances but this vague story I’ve had living in the back of my mind since I was little, came to the forefront at seeing the character of Declan Howell.

#the marvelous mrs maisel#the marvelous mrs maisel season 2#the marvelous mrs maisel s2#tmmm#tmmm season 2#tmmm s2#declan howell#dylan thomas#dylan thomas boathouse#laugharne#carmarthenshire#wales#welsh

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

You should have stayed at home yesterday

Can anyone elaborate or corroborate Pete Paphides' tweet from yesterday?

Heading into #Laugharne for Day 2 of the festival where, at 12pm in The Fountain, I'll be sharing the confessions of a teenage pacifist. Music will be provided by the great Alasdair Roberts. He tells me he's going to tackle OMD's Enola Gay. I dare not believe it until I hear it.

I've witnessed him doing Kraftwerk's Radioactivity and Abba's The Day Before You Came, but not this.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bei den Gondolieri in Venedig hingegen ist -im Gegensatz zu unseren letzten Venedig-Filmen zumindest bei Gilbert & Sullivan und mit der Scottish National Opera- alles wohlbestellt und führt ohne größere Anstrengungen automatisch zu einem glücklichen Ende.

#The Gondoliers#William Morgan#Mark Nathan#Sioned Gwen Davies#Ellie Laugharne#Richard Suart#Yvonne Howard#Catriona Hewitson#Dan Shelvey#Oper#Gilbert and Sullivan#Stuart Maunder#Operette

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Laugharne Castle, Wales UK, was built in the Anglo-Norman era, around 1116, although today only a few beautiful ruins remain.

(Video ©️skyvale aerial Photography)

296 notes

·

View notes

Photo

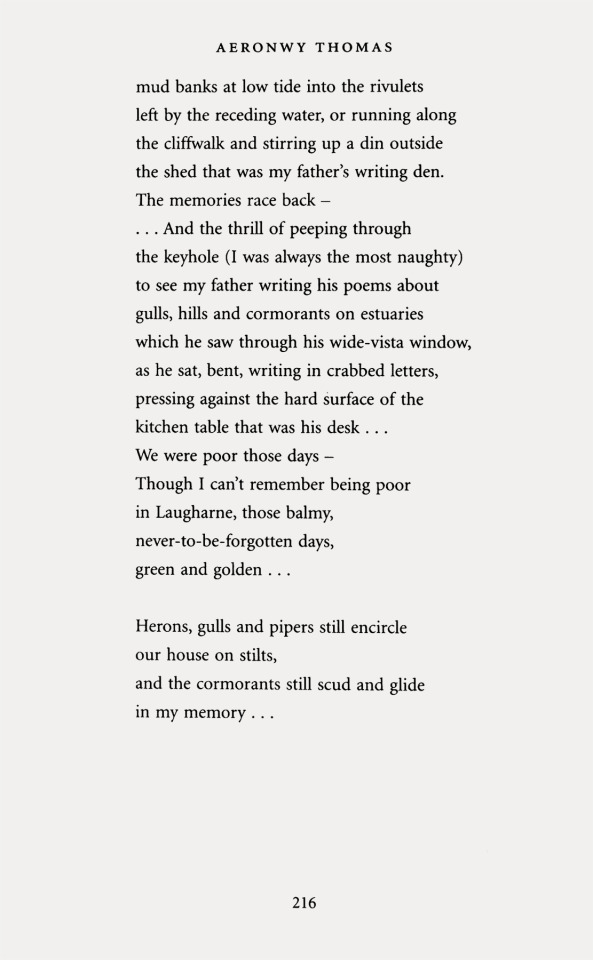

Aeronwy Thomas-Ellis, March 3, 1943 / 2023

Herons, gulls and pipers still encircle

our house on stilts,

and the cormorants still scud and glide

in my memory...

– Aeronwy Thomas-Ellis, (2009), from Later Than Laugharne, Appendix in My Father's Places: A Portrait of Childhood by Dylan Thomas' Daughter, Constable, London, 2010, p. 216

(image: Aeronwy Thomas-Ellis, at her home in New Malden, Surrey, June 1981. © Mirrorpix)

#poetry#photography#book#aeronwy thomas#aeronwy thomas ellis#birthday anniversary#hannah ellis#constable#1940s#1980s#2010s#2020s

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

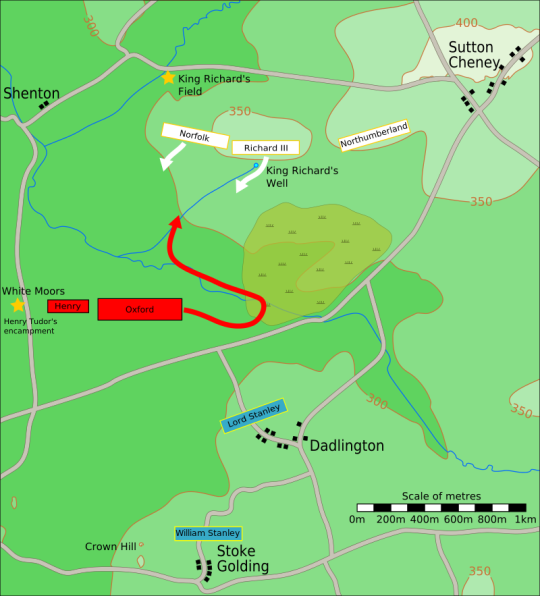

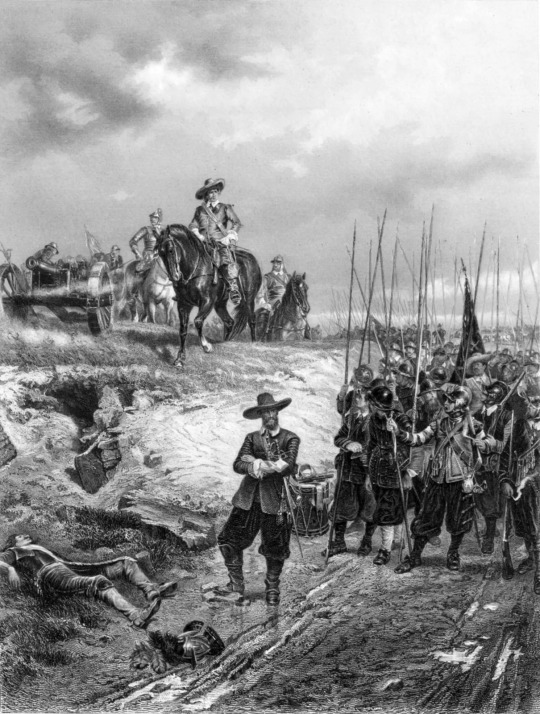

Tudor battles: Bosworth Field

Monday 22 August 1485 marks the beginning of Tudor era.

It was day of the last battle of War of Roses, and the first Tudor battle. We know how it ended. Richard III, last York died in this battle and Henry Tudor emerged victorious and became the first Tudor King, Henry VII.

One could go for hours about politics and intrigue before and all that happened afterwards. We now know that battle happened South of town called Market Bosworth, not really close to it but the name Bosworth stuck.

But what has happened during the battle itself? I am no expert into historical battles, but I’ll try to explain anyway. So here is my ‘short’ view upon this battle:

Before going more about battle itself I wish to make some things clear about the two rivals:

It seems Henry VII was never before in battle(although he probably was trained in fighting as child despite being more or less hostage) and many years of his exile he was kept locked up in small room, not enjoying himself and not beeing able to train properly.

On other hand, Richard III was experienced and skilled warrior.

I strongly I recommend you watch documentary called King Richard III New Evidence of His Spinal Deformity, which you can find on Youtube. It gives great insight to how Richard’s scoliosis affected him as warrior.

Long story short-it didn’t prevent him from being good warrior and expert horse-man. In fact medieval saddle gave his back the support right where he needed, armour helped too.

But there is evidence he suffered from osteoarthritis where his scoliosis turned the most and that probably made him be in great deal of pain. Likely that is reason why during last 3 years of his reign he drank a lot of wine(+ beer which he drank even before)- and despite being very high status before, his diet as King became crazy overindulgence in delicatesies etc.

While we have remeber alcohol content back then was lower(still I don’t know if he still had hang of it or not) it it’s likely he was using wine and food as comfort for his pain.

Scientist think this big change to his diet might have effected him as warrior.

To my surprise Richard’s bones reveal him as somebody of much slender frame than I expected. Nimble on his feet and fast. But not for long time.

Richard’s scoliosis made Richard out of breath faster, to tire faster.

And imo this was one of the reasons why Richard decided to end Henry VII himself. He gave it all he had, knowing the battle would be long otherwise and that didn’t bode well for him. Unfortunately for him, he didn’t manage to kill his oponent.

There are many accounts of the battle.

I have used this article by English Heritage which has some of them in full:

https://historicengland.org.uk/content/docs/listing/battlefields/bosworth/

With interesting commentary and it points out that Vergil’s account(written in England in 1500s and 1510s) and Molinet’s from 1490s, matches in many aspects. Vergil’s just more dramatically written.

Spanish account is confusing, because it has lord Tamerlant which apparently didn’t exist.

(But given the non-unified spelling and source being Spanish it is possible it simply heavilly mispelled name.I tried to look for anything which would sound a bit like it, but can’t find it.

Afterthought: Sometimes lords were called by nicknames, some even more often than their actual titles. However i think another possibility is that it is lord of some Welsh place. Because sometimes when it comes to Welsh castles, the name in English is different than the one Welsh. For example Laugharne Castle, is in Welsh Castell Talacharn. Combined with non-universal spelling, it could then complenetely hide who it was.)

So it is probably not really trust-worthy and it is generally agreed by historions to be based upon hearsay Spanish merchants heard, rather than by somebody who actually was there.

And it in this account that Richard supposedly refused to flee saying 'God forbid I yield one step. This day I will die as a King or win'.

It is also Spanish account which says Henry Tudor saw Richard charging at him and refused to flee. So basically Spanish say-Nobody flee! We want epic battle! You fight it out!

I want that too, I am biased for epicness and logic.

And some of my theories about this battles are probably biased due to this.

But trust me, it is not at all a boring battle and screen as far I know, never gave it proper justice and some webpages are like-the commander was in back in safety! Meaning that person doesn’t know how battles worked, how commanders worked etc.

It is true that by 2nd half of 15th century, commanders often were at back, preferably uphill where they could see what was going on and would move their aditional troops to battle as they thought fit. There is nothing wrong with it.

And in this battle-both men started by doing so.

But we know from accounts of other battles, that not always they stayed at the back! In Flodden, Earl of Surrey and James IV ended up being within lance-distance when James was struck by arrow and died. Hence both of them fought! They didn’t hide!

And just as in Flodden, at Bosworth there were already cannons! And still lots of archers! Either one if they hit you in right place-you’re done for-as James IV’s death proves!

So you can’t say that standing at back of battlefield is safe-hell no! Not the case at all! And you can’t keep saying you know the exact movement of your favourite during entire battle. Only God knows.

But from commanding perspective and given into account Richard tiring more easyily, i think it is unlikely he truly fought in where Norfolk and Oxford(commanders of each vanguard) fought. He kept away from worst of the battle, imo. That is not about cowardice, that is about strategy and tbh knowing when to push foward and when to retreat is sign of not being naive and being mature and experienced.

I could go in greater detail about Oxford and Norfolk clashing. BUt basically, Norfolk was supposed to be aided by Northumberland and by Stanleys-didn’t receive help of either. Eventually Oxford’s men started to win, and Norfolk was killed and afterwards lots of men started to flee. His son was wounded and eventually taken prisoner.

Interestingly, it is said Norfolk was either killed by arrow(which imo is somebody confusing Bosworth and Flodden) or that he was killed by Sir John Savage, which was supposed to be fighting under command of Lord Stanley.

But Lord Stanley couldn’t engage in battle, because he promised to Henry Tudor to not fight Richard and Richard III took his son hostage, wishing to insure Lord Stanley would take action against Henry- And some say Richard even ordered execution of Stanley’s son when Lord Stanley didn’t move in Richard’s favour.

Yet the son survived, so order was not carried out. Why?! Idk, maybe somebody took pity upon the boy and thought it immoral to punish him for something he didn’t do.

It was actually Sir William Stanley’s men who engaged in the battle in the end-Lord Stanley’s brother. So nope, Henry VII’s father in law didn’t come to his aid, his father in law’s brother!

And also, Sir John Savage’s presence shows one very real thing which was like a thing that lots of men did-going around the rules.

Lord Stanley could not formally sent his men to battle to support Henry Tudor. But if some deserted him and joined on their own-it was not his fault!

I am honestly laughing about it because another of Henry’s big supporters, Rhys ap Thomas, welshman who provided him with many troops, has prior promised Richard to attack or aprehend Henry Tudor and his troops if he saw Henry. But he didn’t want to fight him. He supported him. Hence he hid under bridge so that he’d not see him as Henry’s army passed above him.

(They always found a loophole! And it seems Rhys ap Thomas got to battle-so did he at all times made sure he couldn’t see Tudor? Like how did their meeting before battle to discuss strategy go?

‘This is ridiculous! Tell him to come out of his tent!’ ‘I did, my liege. But he says, he made promise to aprehend you if he saw you. So he cannot go to see you but would like to know where he should place the his men in battlefield so they can best shave the boar.’ Boar was Richard’s symbol, shave the boar means to kill Richard.)

But why didn’t Northumberland’s men move? Some say that he made pact with Henry Tudor, but he was imprisoned after Bosworth, alongside with with earl of Westmorland and Earl of Surrey. That word alongside is important, because Surrey 100% was capured at battle. It was speculated that Westmorland might have been in Bosworth and i think it possible.

The Ballad of Bosworth Field mentions 23 nobles in total-but is not really the best source and doesn’t say which side they fought on!

Though those 3 men eventually they were released, they were definitely treated as prisoners. Westmorland was released relatively fast, but his son was esentially taken as hostage. Surrey was imprisoned for longest, for 3 years and yes, it is the same Earl of Surrey who won against Scots in 1513. He was on loosing side at Bosworth.

Northumberland regained the trust of Henry Tudor much faster than others and regained all his previous posts. Imo not due to making pact prior with Henry, but possibly by cleverely saying to him-I didn’t engage my men to aid Richard at Bosworth because I knew your cause was right, my liege.’

(He had way to regain favour and used it.)

Historians think nowadays it might have been due to terrain why Northumberland’s men couldn’t engage-literally couldn’t and it shows that Richard placed his troops wrongly.

It probably didn’t seem like that to Richard from up the hill, but it seems that Northumberland’s men were too close to the marsh and couldn’t move through that terrain, without getting stuck.

(Remember this, before we get to battle of Flodden, because somebody learnt their lesson about marshy terrain.)

Tbh, I am only just stratching the surface of stories of all the notable men from Bosworth. But we can do part 2 next year. Or sooner if you wish to.

I looked at google earth, because it is really hard to imagine the battle terrain from the maps on wiki:

And some things truly are not made clear by it, so I changed it a bit:

I also think it is possible that while Richard charged pass Oxford and rest of Henry’s men, they noted this(his standart, crown on helmet-kind of hard to miss) and deliberately, they moved bit eastward-towards the marsh, to cut him off from rest of his troops. They probably prevented him from retreating same way he came.

But for that to have happened, it means they couldn’t be that engaged with Norfolk’s men. Perhaps by this point, Norfolk already died and his men were fleeing.Northumberland still couldn’t engage, and Richard probably started to realise, that despite being great warrior himself, Oxford was owning his army.

Whetever or not Richard was as good commander as Oxford or not, no longer mattered because Richard’s strategy relied on 3 flanks, but only 2 could engage and he just lost of one those. So he was left with just one flank of his army.

(Imo the narrative that without Stanley’s engaging into battle, Richard would win, is not true.)

It is probably by this point Richard descended to his men, to arouse them to stay and fight. (Because they’d probably fled if he didn’t). But then he spotted his rival.

(Some say his spies spotted him first, then Richard personally. On google earth if you look from where RIchard would aproximately descent to, and to where Henry was aproximately going, it seems he could have spotted him, himself. There was nothing preventing it(unless the weather was bad), so with good eyesight, Richard could logically assume that some smaller force behind Oxford he could see, was Henry Tudor, even if he couldn’t recognize him from distance.

And even though Lord Stanley would not engage in this battle, it would have looked to Richard as if Henry Tudor was going towards Dadlington, to Lord Stanley.

Henry might have merely go in that direction to see bit better what was going on(it was slightly more up, but enough to see better)-perhaps bit eastward to see where the heck was Northumberland(and if he wasn’t going around the marsh to get into his back), but Richard would have probably believed things were going to get from bad to worse for him.

Some say Richard was also enraged to see Henry’s royal banner, because he considered himself the only King on the battlefield.

But I think it was probably combination of Richard realising he could loose, him getting tired and the rage which all combined and caused him charge at Henry valiantly(meaning with great courage and determination).

I don’t know if he ever said it, but imo he certainly at that point thought that he’d either win or die as a warrior King. Richard was not going to flee. He was going to fight it out.

He took his chance, and he got close to killing Henry Tudor.

Question is what prevented him?

And the easy, and untrue answer would be Sir William Stanley’s men.

It was more complicated than that.

Before I dive into it it’d like to point out that Richard’s primary weapon on horseback would be his lance.(that’d be true for most cavalry men.) Only after he no longer had usable lance, he would take out his secondary weapons-probably war hammer or sword. In documentary about his scoliosis they had Dominic train with sword, but also shown reinactors with other weapons-so I think they don’t actually know which secondary weapon Richard’d prefer. And there’d be way more many to choose from than just sword.

But since portrait from Tudor times shows him with broken sword, I think it is possible, Richard’s secondary weapon of choice was indeed a sword.

So Richard and his guard charged(Richard with lance in hand, on horseback) toward Henry Tudor and his guards.

So far very logical, and matching the accounts. But then things get murky.

I am not questioning Richard’s bravery or that he indeed got close to killing Henry.

I am questioning what happened when Henry and Richard and their guards clashed. They didn’t just wave around their swords and lances in the air, before Stanleys arrived. They were killing each other!

Imo, the guards deserve way more credit that they’ve been given!

(And way more screen time! These are most interesting parts of the battle and I don’t think they ever got on screen!)

Because Henry’s guards prevented Richard from killing his oponent and deciding the battle in his favour, before arrival of William Stanley’s men.

Richard’s charge(with his men) seems to have took Richmond’s forces by surprise. Idk how, but several things point to that being the case, despite Vergil claiming Henry saw Richard coming. (Seeing him few seconds before his arrival vs few minutes could be big difference!)

Mainly the fact that Oxford left pikemen in Henry’s guard and they didn’t suround their master to protect him from cavalry charge.

Rhys ap Thomas also left men with Tudor and there were also French mercenaries with him. And yet, somehow they didn’t see Richard charging at them.

Probably because Henry’s men were moving in other direction and Richard came from behind them. They didn’t expect him to pass just next to battling forces and separate from his army.

Richard was really determined to get to Henry Tudor and kill him.

With his lance he killed Sir William Brandon(father of Charles Brandon)- Henry’s standart bearer and then with his already broken lance unseated Sir John Cheyne(he knocked him off the horse). That was no small feat.

While documentary about Richard says Cheyne was over 6′ tall, his bones suggest he was aproximately about 6′8′’!!! (How big was his horse?!)

Sir John Cheyne’s tomb(bellow), look at the seize of those legs!

Really huge knight and Richard unhorsed him, as if he was nothing.

He broke off his lance probably completely by this point and probably took out sword to kill Henry Tudor.

But here the accounts warry. What exactly happened, when Richard managed to get through two of Henry bodyguards? Nobody knows truly.

Spanish account says Henry saw Richard comming, and refused to flee, and Richard refused to flee before that.(So both were brave.)

French account say exact opposite. That when Richard came, Henry dismounted his horse and hid behind his men as coward.

Many websites put this French account among ‘facts’ of Bosworth and it is most spoken about.

Which is more likely to be true? Neither!

Imo, all foreign accounts of any battle, are highly unlikely to be true. If it is not by person who was at least once in that country, don’t believe a word! That is what i learned to do when researching battles. Because the bias, It’s unbelievable! Nonsense some foreign chronicles wrote is sometimes making me question whetever or not they know about which battle they are writing about.

And it is even more unbelievable, that people know some of these chroniclers were working for party which was very biased against one side-and they are not bothered by it! (Unless it is Vergil-whose credibility is apparently 0 despite having best chance to meet survivors of Bosworth-from both sides, while living at English court. But tbh, I don’t trust Vergil that much. Because even if he wished to be truthful and indeed based it upon survivors account, those survivors now worked for Tudors and would not say anything against him.)

Basically they believe Chapuys’s of their time-and for record, I am Catherine of Aragon’s fan and I don’t believe a word from Chapuys.

That account of dismounting is clearly propaganda by side supporting Richard/Yorks, because it doesn’t make sense!

Armoured knight had no reason to get off his horse. There is no logical advantage to it! Henry’d actually be better target for Richard if he dismounted! If he had time to make a move and hide-he could move his horse and his men could just as well suround him while he was on that horse.

Me as amateur can see that and people who seriously studied this battle, don’t see anything wrong with that account?!

That account is illogical. It basically claims Henry was not only coward, but also an imbecile!

And imo this account actually is slighting Richard too. Bear in mind, what I am about to say is purely my theory. Not supported by anything. OK? So don’t claim it is a fact, because I might be completely wrong about it!

But if Richard’s charge was indeed big surprise and he fought so valiantly, imo, it’s possible that after getting through two of Henry’s knights, he got to Henry.

He got close enough to kill and maybe Henry had no time to hide! Even if he wanted to. Only to ready himself to face the more experienced warrior.

He wasn’t experienced enough to fight Richard off imo.

But in full armour, both on horseback, perhaps he managed to at least defend himself for few crucial seconds.

It is purely my theory-but dent in Henry’s right cheek could have been from battlewound. Perhaps from Bosworth. Perhaps from Richard himself.

Richard could try to stab him through gap in helmet. In full armour this could be the most exposed place.

If the helmet was not completely covering Henry’s face or if he had part of it up(which commanders did sometimes to see better) and not have enough time to put it down. It’s possible.

By the way despite coming with this theory before reading Vergil’s account, I seem to agree with what he wrote:

‘But yet Henry abode the brunt far longer than ever his own soldiers would have weened’ (ween meaning think or suppose). Virgil doesn’t directly say Henry and Richard exchanged the blows, but I think they might have. Or at least Henry defending himself while Richard kept attacking.

Somehow Henry, managed to block Richard’s blows, at least partially-gaining that dent in right cheek. And here can be explanation of why Henry dismounted-despite it being absolutely illogical.

Maybe one of the diverted blows hit Henry’s horse. Maybe seriously wounded the animal or even killed it. Henry had no choice but to dismount.

I don’t know if he managed to jump off while animal collapsed or if he got pinned beneath it(even if for just partially).

His horse being done for is only logical reason why he’d dismount, and then it’d be only logical for his men to suround him.

You’d not separate if you don’t have to, during battle, because you’re rather have your back protected by your fellow men, and just focus on fighting enemy on one side. So Henry Tudor would stay among his men.

As footsoldier, Henry couldn’t fight in same capacity as cavalry man and it was most logical if he stood shoulder to shoulder with them, them keeping tight formation.

If he was pinned under the horse, then perhaps they actually did suround him, to protect him, they basically hid him behind them.

(Which would meet the French report, although-not be account of Henry’s cowardice, but rather Richard’s valor and strenght-if he managed to kill or cripple the horse, possibly with just one blow.)

But Richard now faced a problem.

Sir Cheyne’s charge, him putting himself between Richard and Richmond, bought those men few more seconds to react. Richard’s attack lost both moment of surprise and momentum, while he was taking care of Sir Cheyne and he didn’t manage to kill Tudor despite being so close to doing so. And now all of Tudor’s guards were ready to face Richard’s.

It was on!

And William Stanley’s men were quickly aproaching.

Even if Richard wished to try to return to his army, the closest path was now blocked. He could try to go around the marsh towards east and perhaps try to join Northumberland.

(This would not be act of cowardice, but tactical retreat. It happens in battles.)

Potentially Richard’s men faced another issue.

Because perhaps Sir Cheyne was only stunned momentarally. Or not at all. Man of that size and reputable strenght picking himself up fast and attacking from their back! Not good scenario for Richard’s men, though not found in historical records. But certainly my pick on how potentially Richard’s standard bearer lost use of both his legs. Sir Cheyne crushing them both with one blow and cutting through Richard’s men, one by one.

But you might think-that is impossible because that standard bearer is supposed to be with Richard, when he died. And Richard died hundreds of feet from where he clashed with Henry, pushed there by enemy forces! But that is not proven to have happened and it is highly unlikely scenario.

He could be pushed many feet away, but several hundred? No!

He might have disappeared from sight of Richmond, but he certainly was not hundreds of feet away where he died. If I am not mistaken, it was brooch found on the site at that place, which sparked the theory that Richard died so far away.

But that brooch could have belonged to his supporter, who fled. Or perhaps fell of pocket of anybody who looted the dead of the battle.

Stanleys arrival didn’t save Henry directly from Richard’s own attack, but it certainly saved lives of many of his men, and improved their morals thousand times. With newly found vigor, Oxford’s pikemen, welshmen, french mercenaries, Stanleys and other attacked.

It’s likely that as soon as they could, they pushed Richard’s forces towards the marsh-knowing it’d be difficult terrain for them.

(Still close to where two rivals clashed.)

Richard’s men fell one by one, killed by Tudor forces. His own horse got stuck in the marsh.

I don’t believe that ‘Kindom for horse’ happened. But I think given Richard’s scolliosis and him tiring up more easily, he’d have disadvantage on foot. He would wish to be back on horseback, where he had better chance of surviving. So perhaps he indeed asked for horse. It’d be logical for him to do so.

Richard died in thick of his enemies, killed by many blows.

Henry Tudor's first Royal Proclamation, dated 22-3 August 1485, stated Richard III was killed at a place called Sandeford. There is heated debate where exactly that is. In 1858 James Hollings identified 'Sandeford' as the point where the present Shenton to Sutton Cheney road passes over a watercourse that flows from Market Bosworth. Part of the road which crossed the ford was apparently known as 'the Sand Road' - so-called because the inhabitants of Shenton used to traverse it when exercising their ancient right to take sand free from the north side of Ambion Hill - and on this basis it has been assumed that the water crossing was 'the Sand ford'.

Problem is, sometimes stream’s move a bit(even big river can do that), so it is likely that Richard died somewhere near the road and stream, close to the marsh.

If the stream was going bit more south than nowadays in 1485, that basically leaves us with really big section around the road:

Who exactly killed Richard is uncertain, although Molinet’s account and poem by Welsh poet say or suggest it was Welshmen-probably one of men of Rhys ap Thomas. Which is entirely possible given he put many men to Tudor cause.

But it is also possible if not likely, it was not just one man who killed Richard but multiple. King Richard's body shows that the skeleton had 11 wounds, eight of them to the skull, clearly inflicted in battle and suggesting he had lost his helmet.

He was last English King to die in battle, and truly died a warrior’s death.

While his body was then paraded around in Leicester to prove he was truly dead, he wasn’t buried dishonorably as being found in car park would suggest. He was buried in Greyfriars Church, which didn’t survive Dissolution of monasteries.

It is said Henry VII paid 50 pounds for momunent(for Richard’s tomb) in 1495. No small amount at those days.

This might seem strange to us that he paid for tomb of his rival, but imo it could be good move for propaganda, especially if it also depicted Richard with broken sword.

Richard is currently burried in Leicester Cathedral and tbh I hate how modern his monument looks:

But at least he is buried properly.

Too bad his nephews were not given same honour.

So that was bit of shade at the end, I hope you’ve enjoyed it.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Smorgasbord Book Promotions - #Review - #FamilySaga - Sisters by Judith Barrow

Smorgasbord Book Promotions – #Review – #FamilySaga – Sisters by Judith Barrow

Delighted to share my review for the upcoming family saga, Sisters by Judith Barrow, available on pre-order for January 26th.

About the book

A moving study of the deep feelings – jealousy, love, anger, and revenge – that can break a family apart. … Sisters is another absorbing, emotional and thought-provoking creation from the wonderful Judith Barrow. Janet Laugharne

Two sisters torn apart by a…

View On WordPress

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"From Caitlin," Laura Potts

After you, my lighthouse hope, who made a bonfire of my eyes,

the city streets grew old, and I like a lamp candled pale in the cold

coal night, who saw your spotlight glow and fail

here in the crag-black winter of Wales; I who brought to your door

the Irish moors, and London’s charm, and the wheeling, laughing

shorebirds of Laugharne, and made town bars our drama’s stage,

and aged a decade when you played away with local girls

and corner whores; I whose garden full of fruit, folding infants

in our bed, bled hot tears at two a.m. when morning

didn’t bring you home again; I, with the red slits of my eyes,

who saw in evening’s cups of light your hunchbacked-bent-bowed

head, a celestial star, when your words rolled far across miles,

and your eyes in the windowlight took the crack from my smile,

like a movie played in a firefly night; and I, once the lover

whose name you carved into stone, find the winter’s old cold

teeth now blunt in those first frost flakes of November, the annual

month I remember your bones, still gold, in that American bed.

Dead ten years. And still I doubt when, within those great Welsh wells and walls

they ring your passing bell, Dylan, did I ever really know you at all?

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Can L.A. homelessness become 'rare, brief and nonrecurring'?

Earlier this fall, the chief executives of several local foundations gathered at the Southern California Grantmakers offices to discuss expanding their efforts to combat L.A.’s growing homelessness crisis.

The featured speakers were Peter Laugharn, president and CEO of the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation, and Elise Buik, president and CEO of United Way of Greater Los Angeles, both fervent believers…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

youtube

In a parallel universe not far from this one, there has been little else discussed on social media for the past month but speculation about the nature, whereabouts and implications of this performance. And now, fellow travellers, here it is…

0 notes

Text

Sisters... by Judith Barrow #Family Life Fiction #Review @judithbarrow77

A moving study of the deep feelings – jealousy, love, anger, and revenge – that can break a family apart. … Sisters is another absorbing, emotional and thought-provoking creation from the wonderful Judith Barrow.Janet Laugharne

Two sisters torn apart by a terrible lie. In shock after an unbearable accident. Angie lets her sister Mandy take the blame, thinking she’s too young to get into trouble.…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Dylan Thomas and other artists!

Carved bust of Dylan Thomas – Laugharne by Mick Lobb is licensed under CC-BY-SA 2.0

This week, Nick Hennegan celebrates the birth of Welsh poet Dylan Thomas, with performances from Cerys Matthews and Guy Masterson.

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Aeronwy Thomas-Ellis, (2009), Later Than Laugharne, Appendix in My Father's Places: A Portrait of Childhood by Dylan Thomas' Daughter, Constable, London, 2010, pp. 215-216

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Second English Civil War, April-August 1648: ‘The more is the pity, some of those parts are miserably bent to oppose the Parliament and the Army,’

Royalist Rebellions in Wales and England

Source: Encyclopaedia Britannica

THE INCREASING unpopularity of the New Model Army and the Army Council first manifested itself in what was essentially a military mutiny by unpaid troops, threatened with having their regiments disbanded by order of Parliament, in Pembrokeshire in late March 1648. The leader of what quickly became a Royalist revolt, was an unlikely enough figure. Colonel John Poyer, governor of Pembroke, had been a loyal and effective Parliamentary commander during the war, but, along with Colonel Richard Laugharne, strongly resented moves to disband the southern Welsh forces and barred the gates of Pembroke to the Parliamentary adjutant-general, Colonel Fleming, sent to execute the order. Some fighting then took place leading to the death of Fleming, possibly by suicide. With pro-Royal commoner uprisings taking place in the south of England and East Anglia, and Fairfax mobilising forces to bring the Welsh mutineers to heel, Poyer and Laugharne, perhaps feeling they had little left to lose, declared for the King. On 9th April Poyer mustered a force of 4,000 men, all wearing blue and white ribbons to demonstrate their new Royalist sympathies. Crystallising the deep dislike now felt for the New Model Army and the Independents Parliamentary faction in the country, Poyer and Laugharne soon found themselves leading a full blooded popular Royalist revolt in Wales: by the end of April, Brecon, Radnor and Monmouth were in open rebellion and Laugharne was soon in command of 8,000 men and began to march on Cardiff. The threat to south Wales galvanised Fairfax into action and he sent Cromwell to put down the rebellion with force.

The Second English Civil War differed markedly from its predecessor. The conflict of 1643-45 was characterised by regular armies facing off against each other, vying for territory and maintaining negotiations between themselves throughout. Even at its most fierce, there still remained a sincere belief amongst both Cavaliers and Roundheads that once the fighting was over, a settlement would be reached and that peace would return, albeit with new constitutional and religious arrangements in place. However, following Naseby, the complete collapse of the Royalist cause and the rise of a radicalised New Model Army to pre-eminence over Parliament, positions became entrenched. The disparate rebels now declaring for the King had come to regard Parliament and the Army as dominated by incomprehensible Puritan fanatics intent on destroying the very fabric of the Kingdom, whereas the Army were of the view that their victory over the King indicated divine favour, and those who sought to plunge the realm into war again were very literally, fighting against God. This made the second civil war a much more merciless affair, with quarter frequently not given by sides who viewed each other as morally repugnant.

Fairfax faced a war on several fronts. In addition to the Welsh revolt, rebellion also flared in Kent, where men newly converted to the Royalist cause, formed themselves into an army 10,000 strong and threatened to march on London. Meanwhile in Scotland, Hamilton’s Engager force was mustering to invade England from the north as part of its mission to rescue the King. Fairfax therefore broke up the New Model Army further, sending Colonel John Lambert into Yorkshire to defend against the Scots, while he himself remained in the capital to deal with the southern English rebellions. Meanwhile one of Cromwell’s officers, Colonel Thomas Horton, headed off Laugharne’s force at the village of St Fagans on 8th May. In a battle typical of the second civil war, Royalist enthusiasm and bravery on the part of the inexperienced volunteers was no match for the discipline and equipment of the Ironsides, and Laugharne’s men eventually broke. With the defeat of their sole field army, Royalist Welsh hopes centred on Poyer, fortified in Pembroke. Cromwell placed Pembroke under siege, and by early July, realising that Cromwell intended to storm the town, Poyer surrendered. The rebel garrison were treated leniently by the Parliamentary commander and he allowed the defeated troops to return to their homes, but Laugharne and Poyer were put on trial for their lives. Poyer was executed by firing squad and Laugharne was sent into exile. With the suppression of its leadership, the Welsh rebellion was over.

Meanwhile Henrietta Maria’s court in exile in France despatched the Earl of Norwich, a former member of the King’s household, to England to take command of Royalist insurrection there. Norwich was no great military man, but he was a charismatic individual and by 21st May, he had assumed command of the popular forces in Kent and prepared to march on London. Norwich’s strategy was to keep Fairfax distracted to enable the Scottish army to advance south and possibly to free the King from Carisbrooke. This latter aspiration was stimulated by an unexpected mutiny of the Parliamentary navy who had strongly objected to appointment of the Leveller commander Thomas Rainsborough as Vice-Admiral of the fleet. The sailors at Deal, Walmer and Sandwich rejected Rainsborough and declared for the King, placing Dover under siege and forcing the Vice-Admiral himself to seek refuge ashore. Recalling the former Lord High Admiral, the Earl of Warwick to his post, Parliament tasked him with stabilising the situation and ending the risk of the government losing control of the Channel. Warwick succeeded in persuading the key squadron at Portsmouth not to join the rebelllion on 4th June, thus preventing further spread of the naval mutiny.

Fairfax now turned his attention to the English Royalists, who, under former Royal commanders, had now occupied Maidstone, Rochester and Gravesend. After a skirmish with Norwich’s troops at Penenden Heath, Fairfax stormed Maidstone. The fighting was characterised by a street by street running battle that lasted five hours. The Royalists fought well, but ultimately Fairfax’s troops prevailed and the rebels eventually surrendered and were allowed to return to their farms. Norwich led a quixotic assault on London with 3,000 of his remaining men, perhaps hoping the citizens would rise in support, given the anti Parliamentary riots that had taken place in the capital the previous year. However, when the Earl reached Blackheath, he found the city gates closed to him. Many of his followers had deserted by now or refused to leave the familiarity of Kent. Norwich therefore slipped away with a small force of about 500 men and linked up with another Royalist commander, Sir Charles Lucas. The two combined their troops and planned to enter East Anglia where they hoped to stir up further rebellion in support of the King. However, Fairfax’s rapid pursuing march alarmed the Royalists and Lucas and Norwich occupied and fortified Colchester.

Fairfax commenced what turned out to be a brutal eleven week siege, characterised by blockade, sortie and savage fighting with no quarter given. Food ran short for the defenders and the besiegers were emiserated by constant rain and flooding in what was one of the coldest, wettest summers in English history. Lucas also turned out to be a tyrannical garrison commander. By the time the siege ended, the population of Colchester, formerly very opposed to the New Model Army who they viewed as ‘schematics’, longed for liberation from the oppressive military rule of Lucas by the very Roundhead soldiers they had professed to despise. Lucas nonetheless held firm and in the July of 1648 there were some grounds for Royalist optimism. The long awaited Scottish invasion had at last commenced; Royalists were rallying to the Earl of Holland who had raised the King’s standard in Kingston-upon-Thames, and most dramatically of all, Charles Prince of Wales had been collected by the rebellious fleet and was on his way to England.

However Holland’s attempts to raise another Royalist field army failed. He managed to recruit a mounted troop of experienced and motivated men, but they never numbered more than 500. An attempt to take Reigate Castle was unsuccessful and Holland’s force was eventually brought to battle at Surbiton Moor by the Parliamentarians and defeated and Holland was captured. At the same time the Kentish revolt had effectively fizzled out. As the summer reached its end, the situation in Colchester became desperate as hunger became starvation. Ultimately Lucas agreed to terms and the Army occupied the city on 27th August. Norwich was imprisoned, but Lucas, a veteran of Marston Moor and two other non-aristocratic Royalist officers, were sentenced to death and shot. It was a sign of how bitter and vengeful the war had become and how even the normally lenient Fairfax wished to demonstrate by example, the wrongness of the Royalist cause, that enemy commanders should be executed simply for fighting. Fairfax clearly sought to indicate that the civil war was over: any further resistance was the work of rebels resisting divine will, not enemy combatants.

The renegade fleet reached the Thames estuary but Charles Prince of Wales elected not to land. By now the Royalist cause seemed defeated everywhere once more and the hope his father’s subjects would rally now, after the failure of the uprisings was a folorn one. On 30th August a storm scattered the fleet and Charles retreated to Holland. The King meanwhile had distanced himself from the rebellions, perhaps sensing their lack of co-ordination and integrated strategy would doom them to failure. However, Charles’ faith in the Engagement remained strong. With the New Model Army now spread across the country, the King entertained high hopes that Hamilton’s forces, advancing south, could yet transform his fortunes.

0 notes