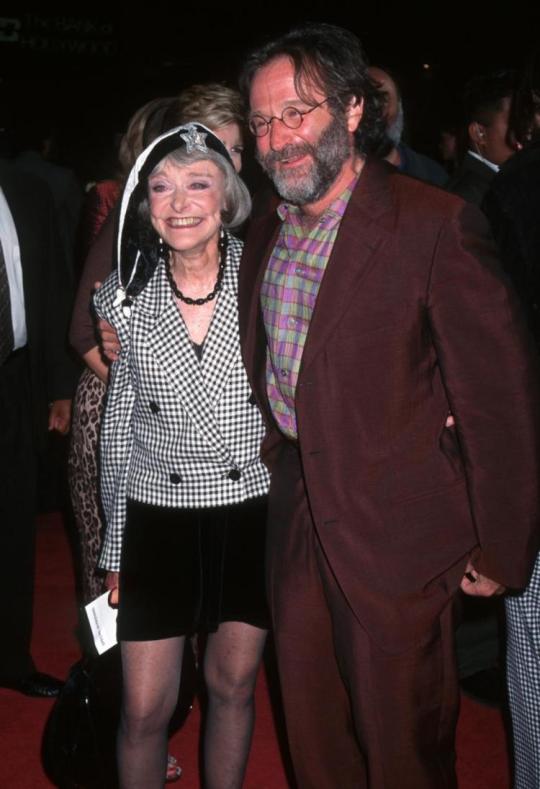

#Laura McLaurin

Photo

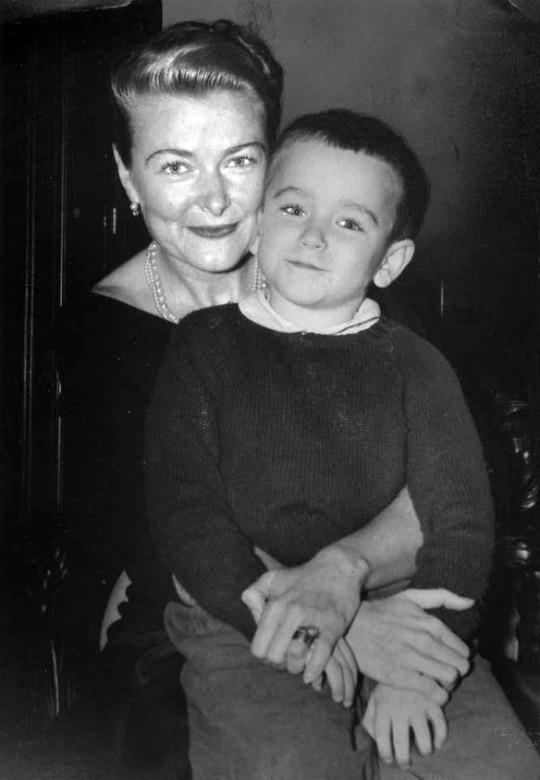

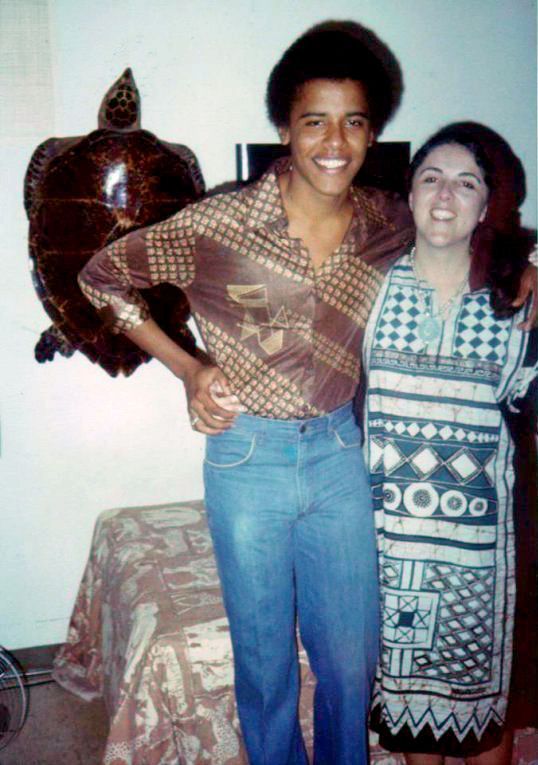

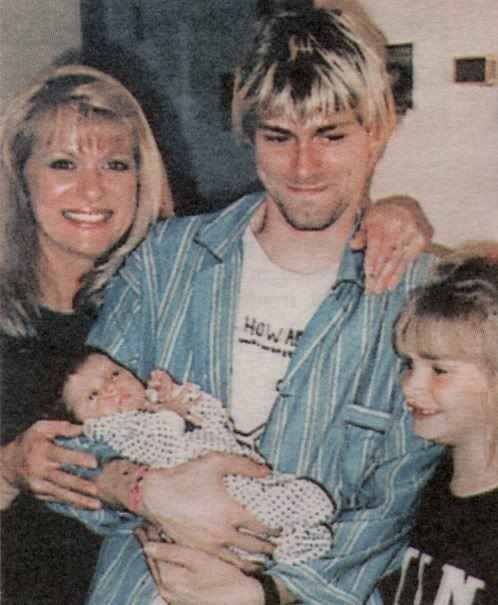

Male Celebrities and Their Mothers

Tupac Shakur & Afeni

Barack Obama & Ann Dunham

Muhammad Ali & Odessa Grady

Michael Jackson & Katherine

Kurt Cobain & Wendy

Robin Williams & Laura McLaurin

Jay-Z & Gloria Carter

David Bowie & Margaret Mary Jones

Leonardo DiCaprio & Irmelin Indenbirken

#tupac shakur#afeni shakur#barack obama#ann dunham#Muhammad Ali#michael jackson#kurt cobain#robin williams#jay-z#david bowie#leonardo dicaprio#irmelin indenbirken#margaret mary jones#laura mclaurin#katherine jackson#odessa grady#celebrities#mothers#gorgeous#beautiful#male

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Frases do ator Robin Williams

Robin McLaurin Williams (Chicago, 21 de julho de 1951 - Paradise Cay, 11 de agosto de 2014) foi um ator e comediante americano. Após conquistar fama interpretando o alienígena Mork na série de televisão Mork & Mindy, e pelo seu trabalho posterior com stand-up comedy, Williams foi destaque em diversos filmes a partir da década de 80.

UM POUCO SOBRE ESTE ÍCONE:

Venceu o Oscar de melhor ator coadjuvante por sua performance no filme Good Will Hunting, de 1997, e também conquistou dois Prêmios Emmy do Primetime, seis Globos de Ouro, dois prêmios do Screen Actors Guild e cinco Grammys. Williams nasceu em Chicago, Illinois. Sua mãe Laura Smith (1922-2001) era uma ex-modelo de Nova Orleães, Luisiana. Seu pai, Robert Fitzgerald Williams (1906-1987), era um executivo-sênior da empresa automotora Ford, em cargo da região do Meio-Oeste.

5 FRASES DE ROBIN WILLIAMS:

"Primavera é a forma da natureza nos dizer: vamos festejar."

"Não importa o que as pessoas te digam, palavras e idéias podem mudar o mundo."

"Veja, o problema é que Deus deu ao homem o cérebro e o pênis, mas sangue suficiente para funcionar um de cada vez."

"Eu pensava que a pior coisa na vida era acabar sozinho. Não é. A pior coisa na vida, é acabar com as pessoas que fazem você se sentir sozinho."

"Ajo como uma criança que não quer ficar entediada. Não faço planos, porque isso é coisa de oficial alemão. As pessoas pensam que tento alternar comédias com dramas, mas não é verdade."

Fonte: 10 melhores frases de Robin Williams

0 notes

Photo

RPAA January Event: Fillet of Solo Kick-Off

Wednesday, January 16

The Heartland Event Space

7006 N. Glenwood Avenue

7:00 – 8:30 PM

Join the Rogers Park Arts Alliance for the free kick-off event of the 22nd annual Fillet of Solo Festival on Wednesday, January 16 at the Heartland Event Space!

Lifeline Theatre's Dorothy Milne will host an evening of performance and conversation with Fillet of Solo storytellers. Learn about the form, the history of the festival, and details on Chicago's many storytelling nights from the people who make them happen — all while hearing stories of different styles interspersed throughout.

Attendees will have a chance to purchase 50% discounted Fest Passes for performances happening January 18 through February 2 in the Rogers Park Glenwood Avenue Arts District.

Fillet of Solo 2019 will feature performances by Laura Biagi, Archy Jamjun, Kristina Lebedeva, Earliana McLaurin, Roberta Miles, Janki Mody, Anne Purky, plus the work of the following storytelling collectives: 80 Minutes Around the World: Immigration Stories, GeNarrations, the kates, The Lifeline Storytelling Project, Loose Chicks, OUTSpoken, Serving the Sentence, Stir-Friday Night, Sullivan High School, The Stoop, Sweat Girls, and Tellin' Tales Theatre featuring Tekki Lomnicki. Over 95 performers will share their stories with audiences over the course of the festival!

Join us for the launch – more info at lifelinetheatre.com/fillet.

0 notes

Text

Call for Proposals: #CiteBlackWomen

Call For Proposals: Feminist Anthropology Issue 2.1: #CiteBlackWomen Posted by Web Maeven | Monday, 12 December 2019 | AFA Blog, Call for Papers, News, Uncategorized Deadline: March 1, 2020 Guest Co-editor: Christen Smith http://afa.americananthro.org/category/call-for-papers/ In this issue, we explore the contributions of Black women scholars to the field of anthropology and beyond. Thinking through our critical traditions, we ask, what scholarship looks like when it foregrounds the thinking of those scholars who have historically been excluded from anthropology’s central conversations? How do Black women’s voices, in all of their diversity (trans, cis queer and non-queer) reshape our modes of theorizing, analyzing, and describing the worlds that anthropologists engage, both past and present? By centering the scholarly innovations of Black women, Feminist Anthropology seeks to challenge citational practices that have silenced, and appropriated the intellectual labors of Black women. Heeding the call of anthropologist Christen Smith who coined the #CiteBlackWomen hashtag in 2017, this issue engages Black women scholars who have been at the heart of the anthropological endeavor, and introduces new generations of anthropologists to the discipline through a lens that reexamines the center from its margins. We recognize that to discuss Black women primarily is not to exclude or ignore other voices, but to address the need to amplify unique experiences and histories carefully and without equivocation. We note the words of the Combahee River Collective: “If Black women were free, it would mean that everyone else would have to be free, since our freedom would necessitate the destruction of all systems of oppression.” To pay special attention to Black women is also to attend to the needs of all of us. As Christen Smith writes, “We must undo the toxic politics of erasing women’s voices across our society, especially in the academy. How can we rethink anthropology’s approach to theory, methodology, and pedagogy so that women of color are not faceless and voiceless? This includes other marginalized populations who have equally been erased from anthropological theory, like indigenous and non-white scholars from the global South.” The journal seeks original submissions across all fields of anthropology that speak to the generous plenitudes of Black women’s scholarly interventions. Archaeologists, linguists, cultural anthropologists and biological anthropologists might ask: How have Black women scholars and marginalized scholars sustained transnational scholarly conversations and how have these discourses and interventions evolved in time (Combahee River Collective; Faye V. Harrison, Chandra Talpade Mohanty; Christen Smith)? What happens to intersectionality (Kimberlé Crenshaw) and Black Feminist theorizing when it is mobilized for anthropological analysis across the fields (Moya Bailey; A. Lynn Bolles; Whitney Battle-Baptiste)? Where does abolitionist and fugitive scholarship lead us in examining the histories, presents and futures of institutions (Maya Berry et al; Brit Rusert; Savannah Shange)? What does anthropological ‘wake work’ look like (Christina Sharpe) in ethnography, language, archive, biology, and the material record? How has language interacted with cultural, biological and material practices to reproduce and resist racial, ethnic, and gendered politics (Jonathan Rosa; Ana Celia Zentella)? How have Black and indigenous scholars challenged anthropology’s approach to voicing kinship, maternity, girlhoods, and households (Cathy Cohen; Aimee Meredith Cox; Saidiya Hartman; Leith Mullings; Hortense Spillers; Mishauna Goeman)? What does the anthropology of religion have to gain from the centering of performance, movement and embodiment (N. Fadeke Castor; Zora Neale Hurston)? How do Black women scholars engage post-humanism; human-plant and human-animal relations; ecological thinking; and the anthropocene (Vanessa Agard-Jones; Octavia Butler; Fatimah Jackson et al.)? How do scholarly understandings of technology benefit from the interventions of scholars who center race, gender, sexuality and class (Ruha Benjamin; Alondra Nelson; Safiya Noble; Laura Wilkie)? How have Black women scholars brought attention to the tyrannies and potentialities of health and healthcare interventions as the work of kinship, development, and empire (Adia Benton; Deirdre Cooper Owen; Faye Harrison)? What methods have Black women scholars innovated, and how do these methodologies benefit the discipline (Dána-Ain Davis; Irma McLaurin)? How have feminist anthropologists grappled with citing sovereignty, queerness, and nationalisms, rethinking the politics of belonging (Audra Simpson; SA Smythe; Deborah Thomas)? We invite submissions that substantively engage Black women’s scholarly contributions and demonstrate their impact on anthropology, and demonstrate how these intellectual interventions “sustain, remix and innovate a lively and heterogeneous set of scholarly traditions,” (Davis and Mulla 2020) towards a richer, more insightful, undisciplined and/or inter-disciplined anthropology. Co-authored and dual lingual pieces are encouraged. If you are interested in submitting a dual lingual manuscript, please contact the editors for more instruction ([email protected] and [email protected]). Manuscripts can be submitted via the journal’s ScholarOne site in all submission categories. Please consult the author guidelines for further details. For full consideration to be included in the themed issue, please submit manuscripts by March 1, 2020. Works Cited Vanessa Agard-Jones. 2012. “What the Sands Remember,” GLQ 18(2 –3): 325-346. Moya Bailey. 2010. “They Aren’t Talking About Me….” The Crunk Feminist Collective. http://www.crunkfeministcollective.com/2010/03/14/they-arent-talking-about-me/ Whitney Battle-Baptiste. 2011. Black Feminist Archaeology. New York and London: Routledge University Press. Ruha Benjamin. 2019. Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code. Cambridge: Polity Press. Adia Benton. 2015. HIV Exceptionalism: Development through Disease in Sierra Leone. Minneapolis and St. Paul: University of Minnesota Press. Maya Berry, Claudia Chávez Argüelles, Shanya Cordis, Sarah Ihmoud, Elizabeth Velásquez Estrada. 2017. “Toward a Fugitive Anthropology: gender, Race and Violence in the Field,” Cultural Anthropology. 32(4): 537-565. A. Lynne Bolles. 2001. “Seeking the Ancestors: Forging a Black Feminist Tradition in Anthropology,” in Black Feminist Anthropology: Theory, Praxis, Poetics, and Politics. I. McClaurin, ed. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 24-48. Octavia Butler. 1979. Kindred. New York: Doubleday. N. Fadeke Castor. 2017. Spiritual Citizenship: Transnational Pathways from Black Power to Ifá in Trinidad. Durham and London: Duke University Press. Cathy Cohen. 1997. “Punks, Bulldaggers, and Welfare Queens: The Radical Potential of Queer Politics,” GLQ 3(4): 437-465. Combahee River Collective. 1977. “The Combahee River Collective Statement.” Deirdre Cooper Owens. 2017. Medical Bondage: Race, Gender, and the Origins of American Gynecology. Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press. Aimee Meredith Cox. 2015. Shapeshifters: Black Girls and the Choreography of Citizenship. Durham and London: Duke University Press. Kimberlé Crenshaw. 1989. “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory, and Antiracist Politics,” University of Chicago Legal Forum, 139-167. Dána-Ain Davis. 2013. “Border Crossings: Intimacy and Feminist Activist Ethnography in the Age of Neoliberalism,” in D. Davis and C. Craven eds. Feminist Activist Ethnography: Counterpoints to Neoliberalism. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books. Dána-Ain Davis and Sameena Mulla. 2020. “Feminist Epistemology and Methodology,” in C. McCallum, M. Fotta, S. Possoco eds. The Cambridge Handbook of Anthropology of Gender and Sexuality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Mishauna Goeman. 2013. Mark My Words: Native Women Mapping Our Nations. Minneapolis and St. Paul: University of Minnesota Press. Faye V. Harrison. 1997. Decolonizing Anthropology: Moving Further Towards an Anthropology of Liberation. Washington, D.C.: American Anthropological Association. Faye V. Harrison. 1994. “Racial and Gender Inequalities in Health and Health Care,” Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 8(1): 90-95. Saidiya Hartman. 2007. Lose Your Mother: A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Zora Neale Hurston. 1938 (2009). Tell My Horse: Voodoo and Life in Haiti and Jamaica. New York: Harper. Fatimah Jackson, Earl Bloch, Robert Jackson, James Chandler, Yong Kim and Floyd Malveaux. 1985. “Influence of Dietary Cyanide on Immunoglobin and Thiocyanate Levels in the Serum of Liberian Adults,” Journal of the National Medical Association. 77(10): 777-782. Irma McLaurin. 2001. Black Feminist Anthropology: Theory, Praxis, Poetics, and Politics. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. Chandra Talpade Mohanty. 2003. Feminism Without Borders: Decolonizing Theory, Practicing Solidarity. Durham and London: Duke University Press. Leith Mullings. 1997. On Our Own Terms: Race, Class and Gender in the Lives of African American Women. New York: Routledge. Alondra Nelson. 2016. The Social Life of DNA: Race, Reconciliation and Reparations After the Genome. Boston: Beacon Press. Safiya Noble. 2018. Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism. New York: New York University Press. Jonathan Rosa. 2019. Looking Like a Language, Sounding Like a Race: Raciolinguistic Ideologies and the Learning of Latinidad. Oxford University Press. Britt Rusert. 2017. Fugitive Science: Empiricism and Freedom in Early African American Culture. New York and London: New York University Press. Savannah Shange. 2018. Progressive Dystopia: Abolition, Antiblackness, and Schooling in San Francisco. Durham and London: Duke University Press. Christina Sharpe. 2016. In the Wake: On Blackness and Being. Durham and London: Duke University Press. Audra Simpson. 2014. Mohawk Interruptus: Political Life Across the Borders of Settler States. Durham and London: Duke University Press. Christen Smith. Afroparadise: Blackness, Violence and Performance in Brazil. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press. SA Smythe. 2018. “The Black Mediterranean and the Politics of Imagination,” Middle East Report. 286: 3-9. Hortense Spillers. 1987. “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book,” Diacritics. 17(2): 64-81. Deborah Thomas. 2019. Political Life in the Wake of the Plantation: Sovereignty, Witnessing, Repair. Durham and London: Duke University Press. Laura Wilkie. 2003. The Archaeology of Mothering: An African-American Midwife’s Tale. New York and London: Routledge. Ana Celia Zentella. 1997. Growing up Bilingual: Puerto Rican Children in New York. New York and London: Blackwell.

0 notes

Text

Smile My Boy; It’s Sunrise

Success is a fickle concept; one objective, and arguably indefinable. And yet, everything in American culture must always be defined- something which Google eagerly spews out. When typing, ‘success, define,’ into a simple Google search; three options will appear. “The accomplishment of an aim or purpose,” “the attainment of popularity or profit,” and “a person or thing that achieves desired aims, or attains prosperity.” Under each definition, synonyms and examples are given, most of which pertain to theatrical success. It seems that to be successful, one must gain fame and wealth. Which is so incredibly, extraordinarily, entirely, stupid. Materialistic, and disappointing.

Why can’t success be something far more meaningful? Something that impacts other people: Inspiration. One can set out without a purpose, yet find one along their path of life, and wind up with one, whether it was their aim to accomplish this purpose in the first place Success isn’t an achieve or fail idea; it’s something so very simple, if only one can step back from their own worlds for long enough to notice the other people sharing the earth.

A man once said; “A doctor’s mission should be not just to prevent death but also to improve the quality of life. That’s why, you treat a disease, you win you lose, you treat a person, I guarantee you win no matter what the outcome.” Success can be treated the same way as practicing medicine; there are far more apparent outcomes of ‘success,’ but there are so many success stories overlooked. So many doctors who couldn’t find a miracle cure, but provided their patients with a miraculous life. Success is a disease, but also a cure. The man who stated the quote, by all standards, fits whatever definition of success. The man realized that it takes looking outside the box, thinking outside the Google definitions, and just a little spark of madness to reach success. The man was Robin Williams.

Williams was born in Chicago, July 21, 1951, to Laura McLaurin and Robert Williams. According to Lifetime’s, “Robin Williams,” article, his mother had been a small-time model, who even when moved to Illinois, was said to keep her California-esque heart, (something Williams clearly stayed influenced by) extended by Genie’s “Laura McLaurin” article, described by Williams himself and others as a “captivating,” story teller, one who loved to laugh, and had a quick wit, something which Robin seemed to develop. Williams’ father, on the other hand, was an executive at for the Ford Motor Company, and a man that Williams described during his winning speech at the Oscar’s as having said, “[in regards to Williams’ desire to be an actor] ‘Wonderful, just have a backup profession like welding.’” Still, he dedicated the win to his late father, clarifying they had a good relationship. (As it turns out, he later expressed on the Graham Norton show that he forgot to thank his mother, something which she didn’t let him down for years to come.) (Source) supports this, with Williams stating, “My dad was a sweet man, but not an easy laugh.” As it turns out, his father’s laughter was the inspiring factor behind Williams’ desire to be a comedian. Hearing his father heartily laughing, at a man on the TV who became in that moment, Williams’ mentor (later corrected as ‘idol’); Jonathan Winters. The influence is more than apparent, sharing the same knack for goofy characters, voices, and wit, as Williams’ would be the first to admit. Between these (sources,) it seems apparent Williams’ comedic nature and clever timing first comes from his mother, and was lucky enough to have financially wealthy parents who were encouraging to let him explore his passions. But the final childhood push to explore that need to be funny, to make other’s laugh, when it came down to it, was a boy’s want of approval from his father.

The Lifetime article goes on to narrate how Williams was bullied as a young child for being overweight, and thus spent many evenings alone instead of out with friends, until later joining track and wrestling, wiping off the weight. Instead of getting back at his tormentors, however, Williams realized he had a knack for being funny, and could use his comedic nature to gain respect from his fellow classmates. The isolation at such a young age lead Williams to need to become more imaginative; in order to keep himself entertained. (Source) confirms that play is one of the upmost important factors a child has in developing, and Williams was forced to be especially creative. Once a bit older, Williams was already adopting his mother’s humor as a guard for himself, and making the realization that if he made fun of himself first, no one else could.

Williams originally went to college for political science, while playing soccer, during which he began improv classes. Realizing he had a knack, he switched schools, began focusing on theater, and soon enough had a full-ride scholarship to Julliard… Which he then dropped out of to move back to Los Angeles to focus on pursuing a career in comedy. It can be concurred that Williams’ intelligence and skills were well versed, and later used to morph him into the comedian he became, able to have a firm grasp on politics, something a frequent factor in most comedy bits, along with the agility from all the sports he took part in, giving himself the advantage of being a very physical comedian. The thought of getting a full scholarship to Julliard, only to drop out in hopes that he could make it as a stand-up comedian is, frankly, insane. But Williams’ ability to make completely outrageous and unbelievable choices was part of his charm, and who he was. No doubt Julliard helped to give him some of the more practical acting skills he later put to use in films like Good Will Hunting and Dead Poets Society, but dropping out of Julliard says far more about Williams than getting into it. He moved away from the safe and practical bet, instead opting for what he was passionate about, knowing perfectly well that he could ultimately fall flat on his face from the decision to pursue comedy over Julliard. However, like shown with many of his movie role choices later, that Williams decided that whether he fail or not, he was going to give it his all. A totally impractical decision, and, just like all his of completely off the wall decisions, one that gave him an edge over everyone else.

That edge was what got him his first major role, although no one knew it would be so big at the time. Williams’ landed an audition for a role on the series Happy Days, which was at the time, desperately trying to knock up ratings, by getting fresh and exciting characters. One of these characters was an alien named Mork, who would only be on for a single episode, as narrated by (Source). According to producer Gary Marshall, “[Williams] was the only alien to audition.” That’s because, when asked to take a seat, Williams instead opted to do a headstand on the chair, validating that all the athletics he did when younger truly did help his comedic performances. Mork was a meant to be a one-time gig, but the character was so popular, he wound up getting his own spin off series, which ran for four seasons. This part, lead Williams to the obvious commercial definition of success. He had the fame, he had the fortune, and he became a successful comedic actor. But that was just the beginning.

Soon after, he landed his first major movie lead role in the live-action version of Popeye, which was a flop, and Williams later frequently joked about and expressed an endearing embarrassment over. However, it was over the course of the 80s during which Williams is credited to being the leader of the comedy renaissance in Los Angeles and San Francisco. He performed a total of five major stand up gigs throughout the time, (source) and, excludingPopeye, seven films, (Source) two in particular which skyrocketed his popularity as a film star. The first released about a decade after the Vietnam War ended, titled, Good Morning, Vietnam. Williams recalls seeing the role as two things he loved doing combined; stand up, and acting, and the character he was playing was mostly himself. However, little this role was to become his first truly successful role; for it was the first one he made that truly impacted his audiences. Williams, along with other crew members, had on numerous occasions, Vietnam War vets come up and thank them for the movie, claiming it was the first movie to be set during the war which accurately portrayed what it was like being a soldier at the time in Vietnam. Now, it can be disputed that the movie’s impact doesn’t hold up as strongly. It’s Williams’ second role that will live on in history.

Dead Poets Society. “Carpe diem. Seize the day, boys. Make your live extraordinary.” It’s a phrase that lives on strong, even today. Williams’ role as Mr. Keating inspired students and teachers around the world alike, as scrolling through, (Source) makes apparent. Person after person list watching him in this role as their inspiration to become a teacher; saying things like, “Feel like I lost a mentor. Robin Williams as Mr Keating changed my path in life. Dead Poets Society led me to teaching, (Cori Marino),” “I wanted to be a journalist. Saw Dead Poets Society, changed plans and became a teacher. Good actors do change the world. (Jacqueline Prins),” and “He made you feel like it matters, that poetry matters[…] I loved the film so much that maybe on one level it is the reason I became a teacher. He understands in the film that education isn’t just one little part of your existence, it is life. It’s the same thing. It’s not just learning Wordsworth by heart, it’s about feeling it and understanding why it’s important, (Jonathan Taylor.)” The list goes on and on, the inspiration Robin Williams left with the world from that movie alone ringing out like bells. It dealt with a subject that most of America has been through; school, and the sufferings of it. The pressure of parents, teachers, the world in general, and how too much of that stress can weigh down on a student, leading them to end their lives rather than continue to struggle. Williams’ character of Mr. Keating, however, is what truly sticks with most people. Mr. Keating, like Williams was blatantly unconventional, having students rip pages from their books, he would hop on the desks, and push his students to pursue their passions over logical classes and hobbies. –The parallel between what Mr. Keating inspires his students to do, and what Williams did as a young man aren’t hard to find. In this role, Williams and the rest of the cast inspired the audience; he made them laugh, he made them cry, but most of all, he inspired them. And it wasn’t only his audiences, but his fellow cast members he inspired; Ethan Hawke validating this, stating that being on set with Williams was a “[…] It’s a high that I’ve chased my whole life since that day with Robin, of losing yourself, within a story.” Hawke credits Williams as his mentor, especially after Williams having booked him his first agent. Williams seemed to have that effect on people. Talk show host Conan O’Brien brought credits Williams as an inspiration, and a brilliant talent, remembering on his show that once when O’Brien was publicly feeling low in his career, Williams (who he didn’t know well outside the show business), bought him a bicycle, knowing O’Brien enjoyed biking. However, being Robin Williams, the bicycle was bright orange, and green, with shamrocks on it, as O’Brien is known for having bright red hair and being Irish. O’Brien narrates him conversation with Williams’ over the phone, saying Williams’ responded; “‘Does it look ridiculous? –Good. Do you look stupid riding it? –Well than that’s good then.” It was that generosity, alongside the unconventional humor, the ability to make everything funny somehow, that made Williams’ such a success, that made fans adore him, and those on sets with him crave to work with him again. Earlier in the segment, he and Andy Richter, talk about the frequent performances that Williams did with the troops; something Williams kept never spoke about, because he did it for their benefit, not the publicity. Robin Williams cared about other people, as any friend, relative, acquaintance, or even passerby on the street seem eager to express. It’s something that nobody has yet to disagree with. He succeeded in changing lives, making people happy, feel like they were special. He succeeded in trulycaring, something that’s tragically hard to come by.

Perhaps the most important lesson to be learned about Robin Williams’ atypical life story is the truth it uncovers about why and how some people are able to succeed. Robin Williams sincerely exemplifies that extraordinary success is largely influenced by nothing more than a little spark of. What defines that madness? In Williams’ own words, madness is “the only way I’ll stay alive.” (Source) Madness is learning not to take the world so seriously, to see the humor within every situation, and to act out abnormally. Say the funny little thoughts that seem too odd or obscure, and not shy away from the world for fear of humiliation. Madness is having fun.

In 1978, soon after his premiere as Mork on Happy Days, he preformed an hour long special at the Roxy, his first televised stand up production. Within the first five minutes, he was wading through the crowd, picking on the members lightheartedly, making connections. Within a moment, he had crawled up to the balcony, walking along the railing, before he was back down and going to the very back of the audience, “changing realities” by making the back of the audience the good seats, and the front the bad. Williams’, after considerable dancing around, he finally proceeded to get back to stage. The physicality of his performance was undone before; so many stand up artists simply standing on stage talking to the audience. Throughout his entire act, he crawls in and out of the audience, taking their things, poking jabs, pretending to be close friends, paying mind to everyone who filtered in and out. His gags were so quick paced; like a child with ADHD’s mind, going from himself to a character, to a bit, to an outburst, to an impression and back again. He pokes fun at white people; regardless of the fact that they’re most of his audience, and it goes over their heads. Williams brings a member of the audience on stage, makes him part of the show. He’s here, there, everywhere, not talking at the audience; he’s talking with them, making individuals feel special, connected, something so many comedians struggle with, so many people struggle with. It’s in this special, he does a bit where Williams’ pretends to be himself in 40 years, traveling back in time and giving the audience advice. Although he never makes it to that extra 40 years, Williams has one slower bit in his show, talks about reality and madness. During the bit about he reality, he questions what it really is, right before sticking his finger through one eye of his glasses, showing that there was actually no lenses in them. He follows this up moments later, telling his audience; “I’m being grotesque, but you’ve got to be, you see what I mean? You’ve got to be crazy! It’s too late to be sane, too late. You’ve got to go full tilt bozo… ‘Cause, you’re only given a little spark of madness… and if you lose that, you’re nothing […] Don’t. From me to you. Don’t ever lose that ‘cause it keeps you alive […] that’s my only love. Crazy.” The shift in the audience at this moment… Before they had been laughing continuously, not a moment of silence. Even through a screen, the sudden intensity of the moment can be felt. This was so very early in his career; and yet already Robin Williams knew what his legacy would be, what would stick with him through his life; that little spark of madness. This is the spark that inspired so many others, that left such big impacts on others lives, and such large holes in their hearts. This is the reason that so many people who never met him mourned his loss, and so many who did are let in absolute shock. When he died, social media flooded with memories of him, from Steven Spielberg, Sarah Michelle Gellar, Steve Martin, President Obama, and hundreds of other celebrities, all describing how he was their childhood, their inspirations, their idol. Everyone who worked with him personally never failed to describe how he would brighten any set, or share an intimate moment they had with him. Besides Conan, other talk show hosts expressed their mourning, like a very choked up Jimmy Fallon, who after attempting to mimic Williams’ enthusiasm, stands on his desk, and announces; “O Captain; My Captain, you will be missed!” -The legacy of Dead Poets Society once again appearing. Seth Meyers thanked him, Nathan Lane shared his best memories, saying remembering how Williams came in on his day off to support Lane during filming on The Birdcage, saying there was “No one was kinder or more generous.” Whoopi Goldberg and Billy Crystal, two of Robin’s closet friends in the film industry, sat down and spoke about him, and Crystal eulogized him at the Emmys’, sighting it as the most difficult situation in his life. With Goldberg, he remembers raising $70 million to help the homeless in America, calling Robin magical, and remembered being in Europe when he died, and being “astounded” by the “outpouring of love” all around the world. This madness caused part of the Genie was written for Robin, the animators knowing only his charisma could truly bring an outrageous character like the Genie to life. This madness made him the only person who could ever play a grown up Peter Pan. This madness made him a success. It made him Robin Williams.

Only someone who was a little mad would continue to make movies like Night at the Museum Three, and film shows The Crazy Ones while dealing with addiction, depression, and early stages of Parkinson’s Disease and Lewy Body Dementia. His legacy will be remembered, whether it’s by saying, “I’ll always believe in you, Peter Pan,” “Genie, you’re free,” “You still exist,” or “O Captain; My Captain.” Or maybe it’s finding that little spark of madness. Robin Williams really did turn laughter into the best medicine. He made his success a cure.

1 note

·

View note