#Luca Guadanigno

Text

« I love you and I love him… you’ll like each other »

Luca is not only a maestro, he is also a diviner, a magician, a master of destiny.

💙💚

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

bones & all (2022) - dir. luca guadanigno

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

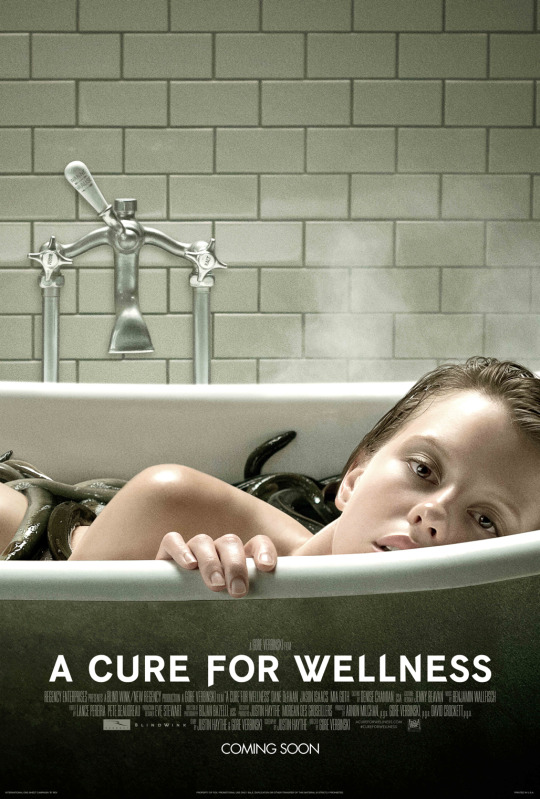

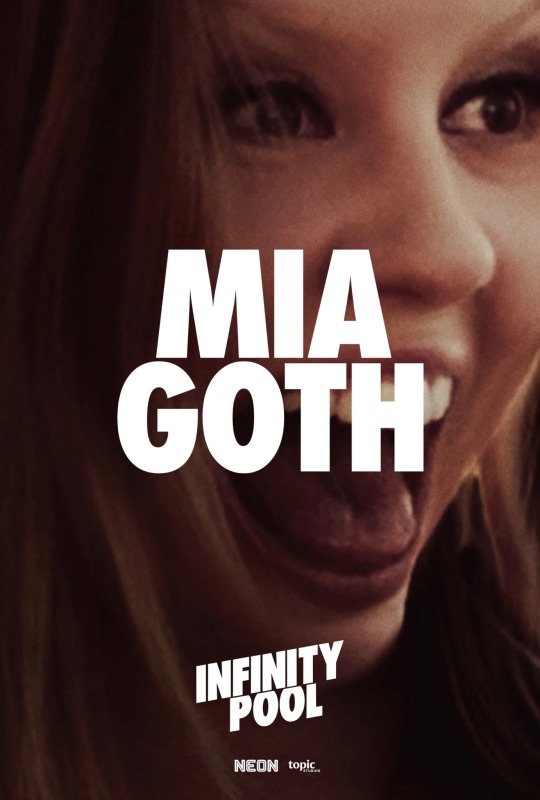

Scream Queen

Mia Goth in

Nymphomaniac Vol. II (2013) dir. Lars von Trier

A Cure for Wellness (2016) dir. Gore Verbinski

Marrowbone (2017) dir. Sergio G. Sánchez

High Life (2018) dir. Claire Denis

Suspiria (2018) dir. Luca Guadanigno

X (2022) dir. Ti West

Pearl (2022) dir. Ti West

Infinity Pool (2023) dir. Brandon Cronenberg

#just trying to clarify she deserved at least an honorable mention before x#like anya taylor joy for the weird girls#i love her work#scorpio#mia goth#nymphomaniac#a cure for wellness#marrowbone#high life#suspiria#x#pearl#infinity pool#film

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

B&A is......what?

As the American premiere of Luca Guadanigno’s latest film, generally admired on the festival circuit, approaches, the PR machine designed to garner award nominations for the project has begun to kick in at ramp speed. It is an interesting and unusual process b/c the horror genre is usually not the stuff of award winning entertainment. The Shape of Water, the 2018 movie that won Best Picture may be the closest, but I would argue that the long-ago Silence of the Lambs was a superior horror entry, although it was neither billed nor promoted as such, and obviously lacked critical elements of the horror genre (a monster (s), vague and explicit danger galore, and wildly terrified characters in the plot) All of this leads to a question of how an unabashedly violent and bloody work (I have not seen the movie, but have two contacts who were able to see it) aimed to shock and horrify audiences might entertain such lofty ambitions.

In the press accounts I have seen, Luca G appears to want to have things two ways at once. On the one hand, he elects to adapt the original B&A story to include graphic, repulsive footage of cannibalism, a religious, legal, and social taboo in every advanced culture in recorded history. But, instead of focusing on the pure evil of predators stalking and killing their fellow humans as routinely as you or I might butcher a deer or dress a partridge to have for dinner, the director tries to manipulate the audience into identifying with the very physically beautiful young cannibals, feeling sympathy for their feelings of isolation/abandonment, and most surprising (to me) accepting the premise that two clearly pathological people could be “a coming of age love story.” Excuse me? Serial murderers do romance? Alert the staff of the DSM; a new category of deviant psychosis has been advanced. Yes, I am being purposely snarky here. I found parts of the published interviews with Luca and Timmy implausible at best and ludicrous at worst. Allegedly, the filmmakers consulted experts on “how cannibals proceed to consume their prey.” Let’s roll the film credits now, cuz I really wonder who such experts are and how they did their research; in the field observations, self report measures, interviews with survivors?

Perhaps imagining that some would object to the inherent repulsiveness of his characters and their choices (no, cannibalism is not a genetic trait, despite the original author’s and the director’s literary conceit to the contrary), Luca elected to try and elevate the blood lust to a commentary on sociological issues of interest in contemporary society. Disenfranchisement, he claims, and the way people forced to the fringes of society cope are integral to the film. Let’s look at this argument a bit more closely. Maren and Lee stalk, murder, and eat fellow human beings; this makes them fringe (Thank God) and disenfranchised? Damn well hope so; they should be imprisoned, perhaps executed for the sheer brutality and frequency of their murders. And yes, I can hear you saying, it’s fiction, it’s a movie, it’s not real. And you are absolutely correct. If B&A was treated as say, The Wizard of Oz, a fantasy movie with similarly implausible characters and behaviors, all well and fine. But no, this movie attempts, apparently successfully, to manipulate the audience into believing these are characters you care about, want to find happiness, see as emblems of some cultural failure. “It’s not my fault human flesh is not available at the local butcher shop.” Oh, please. Beautiful cinematography of the American landscape and a strong soundtrack seduce the audience, like the physical beauty of the main characters, into thinking ‘”These guys aren’t all evil and cruel; they look hot with some victim’s blood all over their faces. I wanna date him (her)”

Another lifeline type argument Luca and some film reviewers have offered is that cannibalism is a metaphor, most probably for queerness and the rejection gays experience in many cultures. Metaphor is a term which has a specific literary and linguistic definition, but in common parlance the usage gets mangled so permit me some precision. Why is cannibalism a poor metaphor for queer behavior? Easy peasy. Cannibalism in this context is criminal, often violent, and anti-social. Queerness has been criminal (still is in some cultures), but is rarely violent, anti-social, or harmful to consenting participants. Queerness is, in my argument, self actualization. Cannibalism is self indulgence at the total expense of another human being. If that doesn’t knock the metaphor argument off the table (metaphorically speaking, wink, nudge, wink), I capitulate. You are working on a different comparison than the one I see.

In fairness, I can’t let Timmy Chalamet at once my sweet skinny noodle, but also a producer on this film who has said he was active in preparing the script, shaping his Lee into a form not in the original novel and acting as a spokesman for the movie, off the hook. In an interview excerpt published today, this naif uttered a word salad explanation for the film and the characters that was, cuz I love him and want to be kind, just inscrutable Despite this man’s consistently incoherent speaking style, people often characterize him as wise beyond his years, an old soul, and possessed of a unique, eclectic intellect. Please. Timmy has never presented himself as an intellect, or even academically average. His talent got him into his high school where his academic performance was not distinguished and he did not finish a single semester of college. His attempt to articulate social trends of the Reagan era, completely misapply the term individualism as a cultural descriptor, and suggest that a sexy murder spree was somehow the result of a broken social promise was sadly cringeworthy. Call in the rewrites team if Timmy is going to be a mouthpiece. No one, and I mean this sincerely, can deliver a script better than he. Free form talking? Not so much.

For any of you who read this or any of my other posts, these ideas has been percolating in my thoughts since a group at a recent cocktail party began discussing the Dahmer television series and we talked for quite a while about the amoral nature of the entertainment media, interested in turning a profit even at the expense of taste, moral posture, or social standards. B&A and the remake of Interview with the Vampire were only tangentially mentioned, but particularly with regard to blood and violence. Some wondered why Luca eschewed explicit gay love scenes in CMBYN, but went full bore bloody in his latest outing. interesting. I wish someone would ask him. Come yell at me anytime. I’d love to know your thoughts.

@mysteryofcharmie @694699@heartsandparts@coloradocharmiegirl@estellaestella@alittlefrenchtree

0 notes

Text

I cannot express how grateful I am that Luca did not include the joint shitting scene in the movie and I cannot quite articulate what emotion I was trying to convey with the furrowed squint my face fell into as I heard it play out in the audiobook, like André your representation of love is so very specificly gross and the worst part is I cannot entirely say that it's wrong

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

If that pink sofa could talk, oh the stories it would tell 😏

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hi Everyone,

I’ve seen CMBYN three times now and I’ve read all the wonderful analyses, Q&A etc. and just thought I’d put my voice out there as well. I’ve mostly posted pics and fun things about the movie, but I definitely have my thoughts (I’ve read the book multiple times as well), so if you’d like to ask questions and get another perspective, feel free to message me, I’ll do my best to keep up. About me: gay male 30+, work in the entertainment industry.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

So, after 23 years my Oliver and I will be reunited on Saturday 6/6. He flies in to SLC and will drive the remaining 250 miles to my remote mountain cabin. We first met 31 years ago but it's been 23 years since we last saw each other, after his wedding. I am not sure where we stand but my love for him is undiminished, unsullied, and very much expectant and hopeful. We are rocketing toward this reunion because of CMBYN. The movie struck such a chord in me, reawakening a passion and intense love for the boy I met when I was a lad of 21. The similarities between my story and those of Elio and Oliver are uncanny. Both take place in Europe in the 1980's, an intense time of friendship, discovery, and of overwhelming, life-changing love that ended in a separation that haunts me to this day. Since those times he has been with me where ever I go, my first thought in the morning, my best thought of the day, my last thought as I drift into sleep. Because the movie (thank you Luca Guadanigno) was so impacful I couldn't ignore or dismiss my reawakened passions so I reached out and prayed that a very old email address was still good. Within a few hours a reply popped up that sent my world spinning. His very first sentence in his reply told me that my instincts, that my attempt to reach out, to reconnect in a meaningful way, were not in vain... "Believe it or not I miss our friendship and think of you often."

I first saw the movie last July. Throughout the next few months I really came to grips with what had happened to me and how my love for him has affected my whole life and all of my subsequent relationships. The emotional revelations came so quickly, although it felt like an eternity, that I finally reached out for help. I began counseling in September to help me gain a better understanding of my runaway feelings and thoughts. The grief and pain of the realization that I've spent pretty much a lifetime without him were overwhelming. I glad I sought that help. Slowly, over weeks and months, I pieced together the entire picture of my relationship, my experience of him.

Now, because of CMBYN, I will be reunited with the most important person I will ever know. I do not know the extent of his feelings. I do not know what will happen. I do not know how this will change me or him. But I do know that it will change me. I plan to tell him EVERYTHING. All of my feelings. All of my lifetime of experiences with him with me always. The height, breadth, and width of my love for him. And even if his feelings have diminished or have changed I will find peace in knowing that he knows, that he has heard from my lips, all that I feel for him.

Thank you to everyone involved with the writing, acting, and creation of CMBYN. You have changed my life forever. #andreacimen #lucaguadanigno #timothychalamet #armiehammer #CMBYN #elioandoliverforever

1 note

·

View note

Text

And back to the happy times…

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

NOT BLOGTOBER: SUSPIRIA (2018)

(Thar be spoilers)

Luca Guadagnino's polarizing remake of the inimitable Argento classic is a beautiful mess. Technically refined and narratively disastrous, it seems to hold a mirror up to the audience, that shows you what kind of viewer you are. I've rarely seen a movie that so divides people, not only according to whether they think is good or bad, but even along lines of what they think it's about. I'm not even sure I can tell you what *I* think it's about, and I even have a hard time telling you whether or not I think it is ultimately good. But, I do think that this complicated experience has given me a better understanding of how I watch movies. I became vividly aware, for instance, that I don't have a real concept of perfection. I feel less concerned about whether a movie "works", than about what kind of job it can do for me personally. Let's say you're a plumber, and you have no idea where my pipes are supposed to go, but you produced a really beautiful set of clawfeet for my bathtub--I may go on to remember you as a pretty great plumber. Maybe you're a groundskeeper, and you absolutely murdered my lawn, but you were willing to come over and sing to my night-blooming flowers? That's a big deal for me. With this in mind, I feel a little embarrassed telling people how well SUSPIRIA 2018 worked for me, but more willing to describe why.

I hesitate to draw too many lines between the very different 1977 and 2018 editions, but I'd like to note that even though he's so often accused (inaccurately, I think) of "making no sense", Argento's SUSPIRIA is actually pretty tidy. An elite dance school is a front for a witches' coven whose administrators will kill anyone who uncovers their true identity. Witches are universally recognized as monsters, and the very fact that they'll kill to stay hidden underlines their basic evilness. No further explanation is necessary to understand the thrust of this story. Guadanigno's version, on the other hand, has lofty aspirations that would require the scope of a WORLD ON A WIRE to fully flesh out. It takes place during 1977's "German Autumn", the peak of the violence surrounding the anti-fascist Red Army Faction. The witches within the Helena Markos Tanz Akademie seem to have a similar leftwing bent--they offer free admission and boarding to their accepted students, respecting the importance of a woman's financial independence, and they denounce psychoanalysis, which has become notorious for victim-blaming in modern times. ("When women tell you the truth, you don't pity them. You tell them they have delusions!") However, these women also define themselves as mutually exclusive with the egalitarian Baader-Meinhof group whose Marxist activities protested the persisting Nazi influence within the contemporary government. The students are instructed to disown their biological mothers to fully accept the spiritual maternity of the academy, which I suppose could suggest the abuse of power by a dictator, or a revolutionary militia, or organized religion, or... There is also the power struggle within the academy itself, between its invisible, historic matriarch Helena Markos, and the younger and more directly involved Madame Blanc, but it is difficult to tell what divergent futures are represented by each woman. In any case, unbeknownst to the students, the dance taught in this institution is a form of spellcasting, in which the choreography projects the witches' will into the world--mainly violently, it seems--but their larger goals remain unclear. In the end, it turns out that the rightful heiress to the academy, the real Mater Suspiriorum, is a young Mennonite from America whose unwitting destiny has been to depose the fraudulent Helena Markos; but, how this functions metaphorically, I still cannot tell you. "This isn't vanity, this is art!" bellows the deathless old hag over an orgiastic final performance in the bowels of the school, and honestly, I find this extremely delightful...but I do not know what, in this story, constitutes vanity, and what constitutes art.

I admit that I find all this rhetoric about power teasingly interesting, even if it is ultimately diffuse and inconclusive. Fortunately, I'm the sort of viewer who is able to sift through the shifting contents of a film like this, and isolate what is most useful to me individually. I found quite a lot to like, slung over the osteoporotic bones of the narrative: It is, above all else, incredibly beautiful. (With the notable exception of Thom Yorke's intrusive pop songs, which took me out of the movie every time) SUSPIRIA 2018 wisely avoids the Snow White-like palette of its ancestor, and the construction of architecture as its main character, focusing instead on fashion and dance. It takes the dusty brown and grey cast of 1970s Berlin and makes of it something ethereally lovely. The formal fabric of the film, composed of uneasy scenes of "realism" and excoriating surrealistic nightmares, is, pardon the term, spellbinding. What is really important for me about this movie is its physicality. Actually, the body itself is the final frontier of power dynamics--might, ethnicity, sex, age--and this is the angle from which the movie makes the most sense to me.

Most dancers will tell you that dance is one of the worst things you can do to your body. Dancers are always sick, always contorting themselves, always touching themselves in some bizarre way. Parts of their bodies are often permanently disfigured by their discipline. Dance is popularly thought of as a matter of beauty and elegance, but practitioners know it to be mortally brutal. SUSPIRIA 2018's focus on dance itself blends nicely with its extreme gore. The movie is outlandishly violent, even considering its origins, but it is important to differentiate gore from violence. Violence, regardless of whether it is in a cop drama or a slasher movie, is always about authority. It is combative, a matter of strength and weakness. Gore is a matter of vulnerability. It describes the fate of the body, the way the body betrays the will and refutes the ego. Extreme gore can reach heights of ecstasy that are conflatable with pornography, but gore carries a deep sadness due to its undeniable finality. It embarrasses the individual, reducing one to the same indeterminate matter as all other individuals in the animal kingdom--not unlike the writhing, interlocked group choreography that makes a chimera of the student body. This SUSPIRIA exposes the limiting nature of bodily identity, whether it is crumpling women up like candy wrappers, dismembering them, eviscerating them, or popping their heads like grapes. Although it is marred by occasional disconcerting camp, the film's perverted crimes against anatomy represent its greatest successes as a work of art.

I've said it before and I'll say it again: Like it or not, gore is for girls. (I use "gore" as a general term for body horror here, for efficiency's sake) Women are defined by a special, involuntary relationship to our insides. A man may go a month without seeing his own blood, but not us. Many men will never welcome penetration, regardless of their sexual orientation, and men are less likely to be forced into this experience of their interiors, than are women. I hardly have to describe the business of pregnancy. So, when I think about the Grand Guignolesque excesses of SUSPIRIA, and in particular its flabbergasting finale, I can't think of this all as a self-indulgent stunt. It seems to me to be an absolute necessity of the story, and the only part of the story that makes perfect sense to me. Gore represents the defeat of vanity, and by that token, I'm happy to call it art.

(I gotta say, I wish the available internet images showed how much more anal than vaginal this goofy thing looked on the big screen, but ya can’t have everything!)

#suspiria#2018#dario argento#luca guadagnino#dakota johnson#tilda swinton#remake#italo horror#euro horror#supernatural#witch#body horror#gore#blogtober

22 notes

·

View notes

Note

hiiii, how do u feel about call me by your name and luca guadagnino?

about call me by your name i have very mixed feelings but its mostly bc in a technical aspect i really like it, its very pleasing to look at in general and i do think it manages to convey the feelings it wanted to but with that being said it still makes me uncomfortable to think about it and watch it because even if the intention is not malicious it still is something that happens a lot irl and could be pretty harmful for people that don’t know how to read into it, i don’t have any really strong opinions on luca guadanigno since im fairly new to what he does but i do love suspiria

1 note

·

View note

Text

Horror, history, and Guadagnino’s Suspiria

There are a number of things that make a film particularly likely to displease me. Firstly, if it is boring. Secondly, if there is non-consensual harm inflicted on people (especially women) for the purposes of the arousal of the audience (director). Thirdly if it doesn’t let you know what it is trying to do. Fourthly, when it does let you know what it is trying to do, but it isn’t doing that. Fifthly, when I feel like a good 30 minutes could be cut from it without it actually losing anything. I would argue that Luca Guadanigno’s ‘cover version’ (his words) of Dario Argento’s 1977 horror Suspiria is certainly guilty of the last three listed above. Nevertheless, it engaged and provoked me enough to take the time to write this.

I am going to say a bit about what I think is good and bad about the movie as well, but I’m going to start in a different place. Several days after seeing the film and having many thoughts and questions about it, I end up here – why is it that Guadanigno chose to ‘cover’ (that is not merely to remake, explode, develop, pay homage to, intervene in) Suspiria, and not, say, a more ‘art house’ piece such as, say Andrezj Zulawski’s Possession (1981), a film with which Guadanigno is clearly familiar. In particular, Guadanigno borrows from Possession the explicit setting of Wall-divided Berlin, and the Wall’s presence in key moments of the film, and the colour changing eyes of key female protagonists. However, these aesthetic choices are not supported by a deeper cinematic integration of the political with the macabre/occult, about which I will say more further on (and if youu have never seen anything by Zulawski, please watch Possession and The Third Part of the Night (1971) at your earliest opportunity, they are in my opinion some of the most extraordinary films ever made).

Argento’s Suspiria is a film that shouldn’t (and in some ways doesn’t) hang together, but is nevertheless very affecting for many viewers. The impression it left on me felt due to its bizarre colour grading and set, the infamous soundtrack by Goblin and the moments where these two came together to produce a kind of grinding yet psychedelic vertigo and a gut-twisting violent death (of which, if I recall correctly, there are 3 in the film). In one sense, there is a great deal lacking in that 1977 version. Dialogue is sparse, poorly written, sometimes inaudible. Everything strong about it is in sound, colour and gesture. Guadanigno’s Suspiria, by contrast, has replaced the garish colours and the idiosyncratic soundtrack with a fuller script, new and deepened characters, several key subplots and backdrops which simply do not exist in the Argento version, a new, far more minimal soundtrack by Thom Yorke, and a different ending. This results in an overly-full setpiece which explicitly foregrounds Germany’s Nazi past, the present day of the film as the days in October 1977 when a plane was hijacked by the a Palestinian liberation group to try to secure the release of imprisoned leftwing German terrorists from a group known as the RAF, an (attempted) meditation on the limits and patriarchal force of psychoanalysis, and even non-conformist Christianity from the US Mid-West (in the new version, the main character, Suzy Bannion, is from a repressive Mennonite clan with a dying mother). An actually rather sparse and impressionistic film has been transformed into a portmanteau of concerns and allusions.

Watching the new version, I wanted all this embellishment and expansion to ‘work’. But I think it doesn’t. One reason for this is that the aspects surrounding the space and subject at the heart of the film – the witch-led dance academy in which an ancient witch is being brought back to life – simply don’t seem to actually have much to do with the film’s centre. It’s not clear enough to me why the psychoanalyst Dr Klemperer (also played by Swinton, and an obvious nod to Jewish diarist Victor Klemperer, who documented everyday life in the Third Reich and survived to tell the tale) wants to protect the women Patricia and Suzy from both the clutches of the witches, and their own psyches, and the Baader-Meinhof gang. It’s not clear why we need to know so much of Suzy’s Mennonite backstory – is it just so we know she’s a virgin, and so she can deny her birth mother at the end in order to lead the coven? It’s not like Guadagnino isn’t capable of making a more spare film; I’m a big fan of his 2009 Io Sono L’amore (I Am Love) which also stars Swinton in a far more nuanced and multifaceted role. The world of Argento’s Suspiria is by contrast fairly hermetic. In the scene I find most upsetting, when the blind pianist’s faithful support dog turns mad and rips his throat out in a deserted square, the municipal buildings are distinctly fascistic. Nevertheless, I think this is an aesthetic and not narrative choice on Argento’s part. It isn’t meant to set us wondering whether his wife died in a concentration camp or not. As soon as you explicitly bring in history, the audience is waiting for a moral judgement – preferably one that has to be tied into the ending.

Here’s another theory as to why this doesn’t hang together. I actually think the only way to make good work that touches on History in the explicit way that this Suspiria does is to be, feel, or make oneself implicated in that history. And Guadagnino, unlike Zulawski, isn’t. So when Zulawski constructs a hidden world, a separate sphere of bodily and psychological horror as he does in the two films mentioned above, he does it as a person who has witnessed and suffered in something of the horrors he alludes to. By contrast, but side-by-side with this, is one of the early scenes in Germany in Autumn (1978) Rainer Werner Fassbinder, one of the contributors to the film (which like Suspiria 2018 is both set in the ‘German Autumn’ of political unrest the year before and in recollections of the Third Reich), plays himself, speaking on the phone to his agent (?) about the suicides of three of the imprisoned RAF members, a moment also touched on, and also through a radio broadcast, in Suspiria 2018. In a scene which I think about over and over, naked Fassbinder says ‘What I think or what I don’t think doesn’t make any difference at all’. Nevertheless, he expresses opinions and anxieties, with growing distress, about the resurgence of a repressive state and an acquiescent public in the middle of the uprisings of recent months. This ensemble film, part documentary, part drama, dominated by Alexander Kluge and Fassbinder, is about as far from a horror film as it could be. Yet it absolutely places this question of implication at its heart, and then proceeds to thread it through interpersonal violence, public mourning, border checkpoints, journalism and sex. And I think Zulawski, through both psychological and body horror, tries to do the same thing – to draw the audience into the problem of their own implication in the conflicts that he presents. In Zulawski, saving a person, or attempting to, from their own actions, has both a personal an a political aspect. In Guadagnino’s Suspiria, it is Madame Blanc, the senior teacher/witch, who provides the only obvious link between the world outside the walls of the dance hall and its interior. A former student, Patricia, who we meet in the first scene desperately seeking refuge from Dr Klemperer the psychoanalyst, is rumoured to have fled to join the RAF (although Sara later discovers her zombified semi-living form in the school’s charnel house of a basement). Commenting on this, Madame Blanc voices approval that someone should have gone to follow their calling, done something brave. It seems to me we are supposed to see Madame Blanc’s approval of Patricia’s actions both as an anti-authoritarian sentiment (the school, we are told, suffered immensely under Hitler but persevered) but also as a convenient cover-up for the coven’s incorporation of rebellious Patricia into their body. It’s unconvincing on either level. The worlds of Berlin 1977 and the Markos Dance Academy can’t be integrated.

I think Argento’s main aim in making his Suspiria was to shock and arouse, to transport people, and disconcert them. Guadagnino has grander ambitions, ostensibly; think one of these ambitions was to make the film ‘relevant’. At the end of the film I felt a kind of dull desire to say ‘Yes, this is a Suspiria for today’. But I don’t think it can – it so carefully attempts to fully allude to the pivotal moments of Germany’s self-horror in the 20th century that it seals them up and takes them away from us. As in the original, the strongest parts of the film are what aren’t fully explained and allowed to bear down impressionistically – the much-talked-about dance-torture ritual which kills Olga in the sealed mirror studio, Sara’s search which goes through that studio into the heart of the coven’s impressive selection of mutilated zombies. Oh, and as with Argento, the soundtrack is very creepy. Subtler, but the foley and sound mixing combined with Yorke’s sensitive and really multi-influenced music makes an excellent combination. I would have quite liked to have the images off for a while in places. Guadagnino should have had the confidence to make this sound a character too.

There is a great deal said already, no doubt, about the relationship between horror as a cinematic genre and the matter of history, but I am not a film theorist. I just love film. And I do think at a time of deep political crisis, for Guadagnino to take this film and make it like this, is an audacious and unreflective act. He has tried to make Suspiria a more political piece, but in attempting to rethink and re-do it, no-one, not the audience, not the director, not even really the characters, is meaningfully politically implicated in totalitarianism, repression, fascism, justice, and so on. So it swirls around beautifully but never lands in a real (and by real I don’t mean realistic) moral and emotional place. The only place it can come to a halt, weakly, is the love story of the psychoanalyst Fritz Klemperer and his wife Anke – a story that has only really provided a kitschy Holocaust backdrop to the film, never the sense that the Holocaust existed in any present. The 1977 hijacking, too, is attractively dishevelled posters, some chanting, indistinct black-and-white faces of historical terrorists, attractively drab Osti set-dressing. When the ghost (?) presence (?) real person (? Who cares) of Suzy, now Top Witch, sits on the ailing Fritz’s bed and tells him that, contrary to the beautiful illusion of elderly Anke which brought him to the mouth of the witches’ Sabbath, Anke did in fact die in Terezin concentration camp (‘She was cold, but she was not alone’), I honestly just didn’t care. The world of the Markos Dance Academy is no more or less real than the Berlin Wall which runs parallel to its façade, and is constantly re-presented to us throughout the film with all the subtlety of a bull in a china shop. In Guadagnino, the personal and the political seem to continue to erase each other, and neither the matters of the state or the matters of the occult seem to have a convincing bearing on the lives and selves of the characters, however much gore and weeping transpires. And though the 152 minutes I spent in this film were often engaging and enjoyable for me, as I curiously reflected on the above I couldn’t help wishing someone had just done a shot-by-shot remake, and that Guadagnino had kept his idealisations of national trauma and forgetting to himself.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The genius of Luca

The enduring strain of the pandemic is eased sometimes by revisiting things which bring us joy. For me, the luminous film, CMBYN, does precisely that. Because film is essentially a director’s medium, the product that we the public ultimately see and love or hate is immutably shaped by his/her vision. Countless actors (think Timmy about Interstellar) are disappointed to see that their roles in the final cut of a movie are dramatically diminished. The old “my best scenes ended up on the cutting room floor” lament comes to mind here. Since I just treated myself to a viewing, here are a couple of my personal takes on Luca’s brilliance in shaping the visual narrative of CMBYN in subtle yet symmetrical ways.

First, think of the way we as viewers are invited, compelled even, to take Elio’s point of view in this story. When Elio sees Oliver for the first time, and then for the final time, what is identical about the two scenes? In neither of these important moments do we see Elio’s face at all. Instead, we must of necessity imagine what is on this man’s face, which not only draws us into the experience empathically, but also makes us use our memory of Elio’s facial expressions. Had we seen a saucy smirk on ELio’s face in greeting Oliver, or his woebegone look of loss as the train leaves the station, would it have served the film and its impact as well? I think not, and knowing just how to achieve that effect is one of Luca’s special gifts behind the camera.

Even more powerful, but no less symmetrical, are two scenes identical in content, but at different moments in the story and each performed by one of the principals. i jokingly refer to these as the sleeping boy scenes. In the first, Elio stares bemusedly at travel-worn Oliver, completely conked out on his bed and thereby missing Elio’s studied sarcasm about “his” room being Oliver’s. Just for a couple of beats, he studies the sleeping guest, but the emotions flitting across his face are exquisitely understated. Interest, irritation, attraction, oh, who gives a shit all fly by. More heartwrenching for the viewer is the sleeping boy scene in Bergamo, where Oliver, never able to sleep through an entire night, turns from the dawn breaking at the window on that final morning to gaze upon the slumbering Elio. The emotions streaming across Oliver’s face are powerful and unlike those in ELio’s earlier scene, sad, dark, and filled with pain. We see grief, guilt, worry, and sorrow at the future he knows is coming. Taken together, these two scenes, mere seconds in length capture the arc of the CMBYN story perfectly, but so unobtrusively, so very subtly that we as viewers don’t feel like we’ve had our faces rubbed raw in the exposition. Love, love, love the artistry.

Bravo, Luca Guadanigno! You wuz robbed at the awards ceremonies, but you, unlike many of your erstwhile fellow nominees, did create a masterwork that will endure for a long, long while.

That’s my opinion and it’s very true ;-).

84 notes

·

View notes

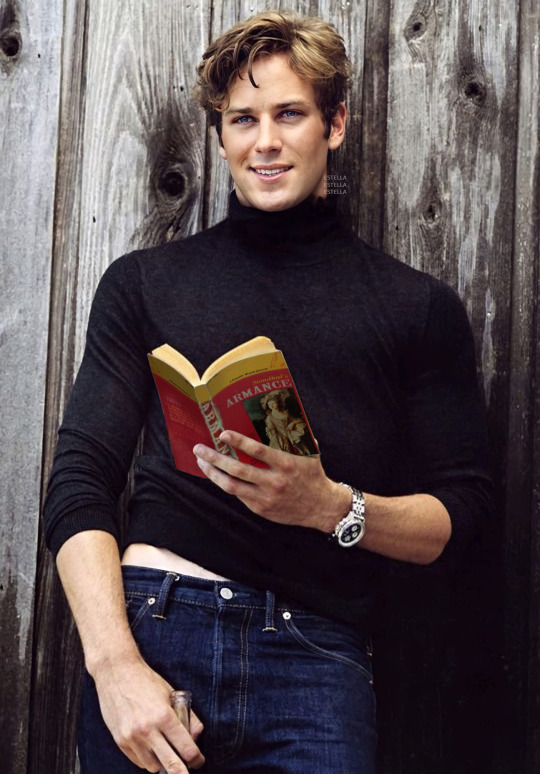

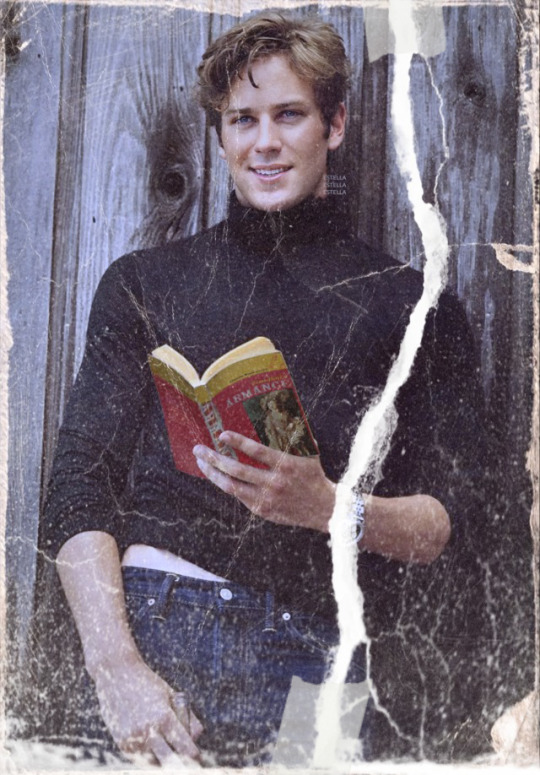

Photo

Oliver holding Elio’s gift, Armance (from CALL ME BY YOUR NAME). Made a version where Elio got mad at Oliver and tore the photo but then later on regretted it and taped it back. Feels like something Elio would do... 😋

Please reblog on Tumblr. Feel free to repost on other platforms, in fact I encourage it. (I wd appreciate a clickable link to me in the credit but no worries if u skip the link.)

#cmbyn#call me by your name#call me by your name 2017#armie hammer#armie hammer edit#elio#elio perlman#oliver#andre aciman#luca guadanigno#armance

167 notes

·

View notes

Text

Best Films of 2017, Part II

5. Blade Runner 2049 (dir. Denis Villeneuve)

“Mere data makes a man … A and C and T and G … The alphabet of you, all from four symbols.”

Making a satisfactory sequel to a widely beloved masterpiece like Blade Runner is a borderline impossible task – the weight of expectation is oftentimes simply too great. In keeping with that wisdom, Blade Runner 2049 is not at all a satisfactory sequel - Luckily for fans of the groundbreaking original, it is much, much more than that. A daringly-conceived blockbuster epic that flies in the face of today’s rapid fire genre filmmaking rulebook, 2049 is the kind of bold, visionary sequel that Blade Runner has always deserved, but most of us lacked the optimism to hope for.

With a gargantuan runtime and an average shot length dwarfing that of the average blockbuster, it’s hard to understate the sheer ambition of what director Denis Villenueve has brought to the screens with 2049. But the true miracle is that the magnitude of 2049’s ambition is matched by its achievement every step of the way, thanks in no small part to the partnership of Villeneuve and cinematographer Roger Deakins, whose Oscar-winning work (!!) on 2049 deserves consideration alongside the best of his unparalleled career. Their collaboration is central to the hypnotic mood and texture of the film – a significant departure from that of Ridley Scott’s 1982 film. It would have been easy for Villeneuve and Deakins to replicate the look and feel of the original – many have done it over the years, with varying degrees of success. But rather than do what was easy, they took the original’s oft-imitated cyberpunk world and filtered it through their own creative lens – coming out on the other side with some of the most indelible imagery the year in cinema had to offer. That the film also treads novel thematic territory in the well-worn debate on the existential border between man and machine, cements 2049’s status as one of the all-time great film sequels.

In keeping with the film’s heavy Tarkovsky influences, Villenueve focuses more on finding the right way to ask the hard questions than on constructing tricky ways to answer the easy ones. But Tarkovsky, as brilliant as he was, never made a film that looked anything like this. It’s with this delicate marriage of grand imagery and even grander ideology that Villinueve has defied the odds and done what most thought was impossible … He’s made a brilliant follow-up to an undisputed masterpiece.

In doing so, he just might have made one of his own.

4. Lady Bird (dir. Greta Gerwig)

- Lady Bird. Is that your given name?

- Yeah.

- Why is it in quotes?

- I gave it to myself. It’s given to me, by me.

All too often, authenticity in filmmaking is synonymous with directorial transparency - passive camera and observational direction have become the du jour techniques to achieve a realist aesthetic. But there is a special authenticity to crafting a film that fully and authentically inhabits a specific point of view. Greta Gerwig’s splendid semi-autobiographical debut Lady Bird is just such a special film. Far from being passive and observational, Gerwig’s distinctive voice as an actress transitions beautifully behind the camera as she bottles up all the emotional tumult of high school and unleashes it through a powerhouse performance from one of cinema’s best young actresses.

Though a realistic Oscar push never quite developed, Soairse Ronan has now delivered two performances more than worthy of the honor - at 23, she is already far overdue for greater recognition. As Christine “Lady Bird” McPherson, she works in perfect harmony with Gerwig to deliver big-time laughs and well-earned tears while casting even the most tired coming-of-age tropes in a fresh new light. And, while it’s not clear whether it’s even possible to steal the show from a performer of Ronan’s caliber, leave it to the reliable character actress Laurie Metcalf to give it her best shot. Her big-hearted but overly-critical mother is career-best work that often serves as the film’s emotional backbone. She’s the perfect foil to Ronan’s bursting-at-the-seams teenage rebel, and their fraught relationship is the crux of Gerwig’s film.

The best thing that can be said about Lady Bird – and there are more than a few great things to say – is that it simply rings true. It’s earnest portrayal of a young girl clashing against the boundaries of her world, and herself captures something deeply true about the contradictions of young adulthood. Despite it’s modest packaging, Lady Bird is a genuinely moving and supremely confident debut, bursting with creative ambition and boasting immaculately-realized characters expressing ideas that resonate with audiences beyond the film’s pointedly narrow scope. If that’s not the sign of a brilliant filmmaker, then I don’t know what is.

3. Call Me By Your Name (dir. Luca Guadagnino)

“Nature has cunning ways of finding our weakest spot.“

On the heels of Moonlight’s stunning Best Picture win, few would have expected another masterpiece of LGBTQ cinema to emerge so quickly. But the consensus best film from the Sundance Film Festival’s 2017 iteration was just such an effort. Luca Guadagnino’s entry to the festival was immediately pegged as one of its more buzzed-about titles. His previous two films, 2009’s I Am Love and 2015’s A Bigger Splash - both featuring characteristically excellent performances from Tilda Swinton, with the latter boasting a very uncharacteristically off-the-walls and thoroughly underappreciated turn from Ralph Fiennes - established Guadanigno as a premiere actor’s director. But Call Me By Your Name showcased a newly-subdued directorial style, giving his impressive cast of players even more room to shine.

On this note, it’s hard not to point to Guadignino’s pairing with 2017 breakout Timothee Chalamet as a gift of fate. Working with Guadanigno, Chalamet is revelatory. He delivers a performance with nuance and complexity far beyond his years. As the film follows Chalemet’s Elio finding first love, he projects confidence only to be betrayed by moments of utter vulnerability, hitting those extremes – and every note in between – with absolute perfection. In this year’s Best Actor category, Gary Oldman had the perfect industry narrative, but Chalamet gave the most deserving performance – no one will ever convince me otherwise. Surrounding Chalamet’s masterful work is a stellar ensemble, of which Michael Stuhlbarg is the clear standout. In hands-down the best moment in the year of film, Stuhlbarg delivers a monologue for the ages with his voice hardly rising above a whisper. His is an absolutely brilliant performance that, like most of his unerringly impressive character work, has been criminally ignored.

Call Me By Your Name is destined to join the ranks of the all-time great LGBT romances, but it’s thematic reach and the appeal of its characters are universal. It’s a masterpiece of storytelling that perfectly captures hesitant intimacy blossoming into the kind of love that burns bright and leaves marks that last a lifetime. Guadagnino guides us gracefully through the tender connection at the film’s center without sacrificing the complexity of Elio and Oliver’s emotional journeys. These moments of self-discovery – and discovery of a part of yourself in another – are never straightforward endeavors, but Guadagnino’s warm camera conjures the melancholic beauty in every intricate detail as though he’s recalling a fond memory. Times like these call for films as tender, earnest, and full-hearted as Call Me By Your Name. It’s unmissable.

2. Dunkirk (dir. Christopher Nolan)

“You can practically see it from here ...

What?

... Home.”

Leave it to Christopher Nolan, who already revolutionized the superhero movie, to produce a war film unlike any I’ve ever seen. Like Saving Private Ryan before it, Dunkirk throws out the playbook and finds great power outside the bounds of convention. An absolute masterclass in structure and formal editing – in many ways more ambitious even than the groundbreaking structure of Nolan’s grandiose mindbender, Inception – Dunkirk juggles three different storylines, all of which occur over different timeframes, until they all converge in a breathlessly tense climactic sequence. Weaving these threads effectively is a gargantuan task, but Nolan proves himself more than up to the challenge.

From a directorial perspective, Dunkirk is not far removed from Nolan’s previous efforts. His precise technical command and vision for spectacular set-pieces is nearly unmatched in modern studio filmmaking – but this isn’t news for anyone who’s familiar with his previous work. Where Dunkirk improves dramatically over Nolan’s previous efforts – particularly his more uneven films, like Interstellar and The Prestige – is on the page.

One of the biggest knocks against Nolan as a filmmaker has always been his over-reliance on expository dialogue. (Honestly, how many different perfunctory monologues did it take for him to explain Inception’s dream-within-a-dream structure? Or wormhole travel in Interstellar?) So how did he respond when writing Dunkirk? With a ruthless editorial pen, he chipped away at each bit of dialogue until all that remained were the truly essential elements. The result is the most sparse film of Nolan’s career – it also happens to be the best.

Even with the lack of dialogue Nolan’s cast is given to deliver – or perhaps precisely because of it – Dunkirk is filled with memorable ensemble performances. Cillian Murphy’s shellshocked sailor, Tom Hardy’s steely, resilient pilot, Mark Rylance’s calmly resolved civilian, and yes, even Harry Styles’ fearfully cruel foot soldier, all leave a lasting impression despite limited screen time. It’s a testament to the efficacy to the show-don’t-tell philosophy when embraced by a director as immensely talented as Nolan.

Filling in the gaps is composer extraordinaire Hans Zimmer’s droning score, which might very well be the best, most thematically effective work of his career. Propelling and underlying the cacophonous atmospherics is the simple tick of a clock – so ubiquitously present that you only notice it when it suddenly drops away. It’s a simple gambit that makes for one of the most thrilling moments of the cinematic year. Without Zimmer’s score, it never would have materialized. His work elevates the film – there’s no greater compliment that a composer can be given.

Like The Dark Knight before it, Christopher Nolan has also crafted Dunkirk to be uniquely resonant in the present geopolitical landscape. It’s a morally resolute film, firm in its assertion that certain battles are worth fighting and unambiguously optimistic about the willingness capacity of good people to do so, no matter the cost. It’s an empowering message, harkening back to a day when Western civilization was left with no choice but to do away with equivocations and rise up to face an unambiguously evil force at work in the world. As we see hints and shadows of that same fascistic ideology re-emerging in our present politics, Dunkirk reminds us that we are capable of defeating it, but only at a terrible cost.

1. Phantom Thread (dir. Paul Thomas Anderson)

“Kiss me my girl, before I’m sick.”

With each subsequent entry to his already-legendary filmography, Paul Thomas Anderson further stakes his claim as American cinema’s greatest living auteur. His latest, Phantom Thread marks a particularly fascinating step along his journey to filmmaking greatness. As with all of Anderson’s films, there’s more to Phantom Thread than initially meets the eye. What initially appears to be a peculiar period romance slowly reveals itself to be a devilishly subversive take on power dynamics and love. The film’s austerity and elegance belie it’s prickly subtext, but (of course) it is this exact contradiction that makes Phantom Thread so damn interesting ... There’s not a film this year that has more frequently occupied my thoughts.

In what is reportedly his final role, Danial Day-Lewis is as impressive as ever, doing away with the towering theatrics of his best-known performances (there’s hardly a hint of Daniel Plainview or Bill the Butcher, here) in favor of the meticulous character work that initially brought him to critical esteem. In his hands, Woodcock’s cartoonish mannerisms feel thoroughly organic with nary a false beat to be found, while bringing Anderson’s words to life with extraordinary skill. Lines that could feel like throwaways to another actor take on legendary status as delivered by Day-Lewis. If it is indeed the final time that he will be gracing our screens, then he’s picked a finale befitting his storied career.

As if taking cues from his star and uncredited co-writer, P.T. Anderson directs his latest masterpiece with an uncharacteristically gentle hand. Thrown to the wayside is the visionary flash and technically prodigious camerawork that defined his earlier greats. Instead, Anderson hones in on his unmatched sense for interweaving character and theme and lets his actors the heavy lifting in largely still frames. Unsurprisingly, the results are brilliant, the product of an assured and confident master working at the very height of his powers while refusing to lean on his past successes.

But while the continued collaboration of Anderson and Daniel Day-Lewis sits at the center of any assessment of Phantom Thread, it’s greatness is often solidified by the masterful contributions outside of this titanic duo. Another frequent PTA collaborator, Radiohead guitarist Jonny Greenwood, turns in his best work since his groundbreaking score for There Will Be Blood. His lush piano work and elegant strings match the film’s beats to perfection, rooting out its subtleties and amplifying them beautifully. And Day-Lewis’ co-star, the previously unknown Hungarian actress Vicky Krieps, may well be the most exciting discovery of the year. Acting alongside Daniel Day-Lewis must seem a daunting task to even the most experienced of thespians, but Krieps fearlessly matches him step for step.

Phantom Thread, though it’s the director’s most austere film to date, is a P.T. Anderson film, through and through. By that I mean that it’s deeply strange and continually surprising, but ultimately narrows its gaze on something uncomfortably and fundamentally true about our common human condition. It’s gorgeously made and subtly provocative cinema from a virtuoso filmmaker … What more could you ask for?

#best films of 2017#best films of the year#film review#movie review#film#cinema#phantom thread#dunkirk#call me by your name#lady bird#blade runner 2049#denis villeneuve#christopher nolan#greta gerwig#luca guadagnino#saoirse ronan#timothee chalamet#paul thomas anderson#daniel day lewis

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aesop Skincare

Like chemists in a lab, I remember trying products of all textures in my best friend’s bathroom.

“This one,” she said as she dropped a honey-like gel into her opened palm. “Is like a barrier between your skin and pollution. It traps everything.”

She warmed it up between her hands and pressed it into her skin. I was mesmerized — I had truly never interacted with skincare in this way before.

The honey-like gel was Aesop’s B Triple C Balancing Gel, a brand and product with a cult following I soon found out. As I researched the brand and its product range, I began to fall deeper into curiosity. It seemed to be a perfect marriage of prescriptive skincare and thought-provoking art, and it showed me that a methodical approach to beauty does not have to be so sterile.

It can be intimidating when you first approach Aesop. Sleek, uniform bottles and jars line the walls of their shops almost like an art piece that you are not allowed to touch or interact with. The experience may seem otherworldly until you encounter the centerpiece of every space, the basin, which is where engagement with the product is encouraged through experimentation and demonstration.

Though the price tag is not initially inviting either, I soon found out that everything has a specialized purpose in the skincare ecosystem. Not every product is justifiable for the cost either, and that’s the beauty of it to me. I can honestly count on one hand the products that I am willing to invest in, and it’s different for everyone depending on their skin characteristics and lifestyle factors, such as dryness, oiliness, environment, travel, etc. Put simply, what I think is worth the cost may not be worth it to others, but the freedom to choose where and how you invest in your personal care is priceless.

Researching further, I found that each Aesop space has its own unique design and is meant to weave into the fabric of its host location. This is timely, as gentrification sweeps through more and more corners of cities, causing cultural erasure and pushing out the very essence of a place — its people. It’s admirable and relatively unheard of for a corporate company to work locally within the community to make their presence a non-intrusive collaboration, and Aesop does it thoughtfully and with care.

Aesop also features and supports the arts, something that is embedded in their brand ethos. They feature quotes from literary figures on product jars and the shop’s reusable canvas bags, as well as employing local artists to design and furnish their retail spaces. One of my favorites to date is their collaboration with Luca Guadanigno, wherein the Italian filmmaker and screenwriter partnered with the brand to design their first store in Rome and paid homage to its ancient and sacred history. Their monthly emailed Ledger is also worth a subscribe and further supports the ways in which intelligent, creative touches can exist non-superficially in retail.

It’s an interesting thought that everyone can be an experimenter of different formulations, as creatively or as regimented as they would like to be. Everyone is ultimately their own expert of their skin, and I admire a brand that empowers that notion and encourages thoughtful consumption. I’ll link my essential Aesop products below, and I’d love to hear about your thoughts, as well as any products you have or are curious about trialing.

My essential Aesop products:

-B Triple C Facial Balancing Gel

A lightweight, aloe-based moisturizing and balancing gel with the added benefits of vitamins B and C to protect and repair the skin. It made my skin so smooth that I stopped wearing foundation and heavy makeup, which condensed my makeup routine significantly and saved me $.

-Camellia Nut Facial Hydrating Cream

Great for dry skin and absorbs quickly so it doesn’t feel like a cream is sitting on top of your face. Soothes irritated skin and smells like sandalwood.

-Parsley Seed Eye Serum

I had never used an eye product I liked before this one. It’s aloe-based and soothes puffiness, plus has the added benefits of concentrated antioxidant and vitamin content. Especially great if you are in a warm, humid, or polluted environment.

-Herbal Deodorant Roll-On

The first natural deodorant that has worked well for me and not caused irritation or strange stains on my clothes. Smells clean and herbaceous like sage. Alcohol and aluminum free.

-Redemption Body Scrub

This scrub is the best one I’ve used for my dry, sensitive skin type. Small pieces of bamboo are the exfoliating agent, rather than plastic beads. It’s better for the environment and provides an even, non-irritating exfoliation. It smells “clean” in the woodsy sense, like pine and spruce.

Images by Victoria Roccaforte and Erika Nathanielsz.

#aesop#aesop skincare#b triple c#skincare#beauty#beauty blog#resurrection#luca guadagnino#Dennis Paphitis

0 notes