#Luddites

Text

The new Luddites—a growing contingent of workers, critics, academics, organizers, and writers—say that too much power has been concentrated in the hands of the tech titans, that tech is too often used to help corporations slash pay and squeeze workers, and that certain technologies must not merely be criticized but resisted outright.

I’ve been a tech journalist for a decade and a half; I did not begin my career as a critic. But what I’ve seen over the past 10 years—the rise of gig-app companies that have left workers precarious and even impoverished; the punishing, gamified productivity regimes put in place by giants such as Amazon; the conquering of public life by private tech platforms and the explosion of screen addiction; and the new epidemic of AI plagiarism—has left me sympathizing with tech’s discontents. After years of workers and citizens serving as Silicon Valley’s subjects, a movement is now under way to wrest back control. I consider myself a Luddite not because I want to halt progress or reject technology itself. But I believe, as the original Luddites argued in a particularly influential letter threatening the industrialists, that we must consider whether a technology is “hurtful to commonality”—whether it causes many to suffer for the benefit of a few—and oppose it when necessary.

219 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hollywood is the single best example of mature labor power in America

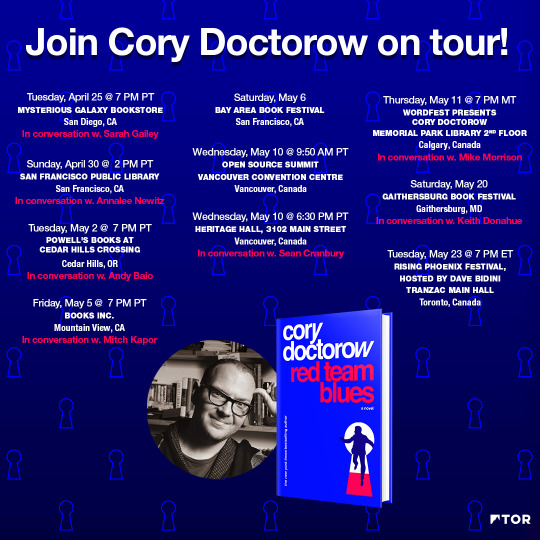

This afternoon (May 6), I’ll be in Berkeley at the Bay Area Bookfest for a 3:30PM event with Glynn Washington for my book Red Team Blues; tomorrow (May 7), it’s an 11AM event with Wendy Liu for my book Chokepoint Capitalism.

Weds (May 10), I’m in Vancouver for a keynote at the Open Source Summit and a book event at Heritage Hall and Thu (May 11), I’m in Calgary for Wordfest.

The Writers Guild is on strike. Hollywood is closed for business. The union’s bargaining documents reveal a cartel of studios that refused to negotiate on a single position. This could go on for a long-ass time:

https://www.wga.org/uploadedfiles/members/member_info/contract-2023/WGA_proposals.pdf

If you’d like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here’s a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/05/06/people-are-not-disposable/#union-strong

The writers are up for it. A lot of people are saying this is the first writers’ strike since 2007/8, but that’s not quite right. That was the last time the writers went on strike against the studios, but in 2019, the writers struck against their own talent agents — within the space of a week, all 7,000 writers in Hollywood fired their agents. They struck against the agencies for 22 months.

https://deadline.com/2023/04/hollywood-strike-writers-guild-studios-talent-agencies-1235333516/

The agencies had consolidated down to four major firms, two backed by private equity who loaded them up with debt that could only be repaid if the agencies figured out how to vastly increase their profits. They did so, by unilaterally switching the way they did business with their clients. Instead of taking a 10% commission on the creative wages they bargained for, the agencies started to take “packaging fees” from the studios for putting together a writer, director, stars, etc. These fees came out of the same budget that the talent got paid from, so the higher the fee was, the less the talent made. Soon, some showrunners were discovering that they were getting 10% and their agents were getting 90%!

The agencies weren’t done, either: they were building their own studios, and planning to negotiate with themselves on behalf of their clients. The writers said fuck this shit. They issued a code of conduct ordering the agencies to knock all that shit off. The agencies swore they’d never do it. Why should they? Every job these writers had ever done came through an agency, and the agencies were staffed with the toughest, most obnoxious negotiators on the planet.

They were sure the writers would cave. After all, the top tier of writers had been handled with kid gloves by the agencies and not ripped off to the same extent as their jobbing, workaday peers. They’d break solidarity and the union would collapse, right?

Wrong. Twenty-two months later, every one of the agencies caved on every single point. Bam. Union strong.

(Want to learn more? Check out Chokepoint Capitalism, Rebecca Giblin’s and my book about creative labor markets:)

http://chokepointcapitalism.com

Now the writers are back on strike and it’s triggered a predictable torrent of anti-worker nonsense (“striking writers will lead to public indifference to torture!) (no, really) (ugh):

https://www.readtpa.com/p/on-the-tv-writers-strike-dont-fall

One common theme in these bad takes is that writers aren’t real workers, like, you know, coal miners or Starbucks baristas. They’re coddled intellectuals, and haven’t the intelligentsia been indifferent to proletarian struggle since, you know, time immemorial?

This is wrong in every conceivable way. For starters, it’s ahistorical. Lord Byron and innumerable other toffs and poets and such were right there with the Luddites, demanding labor justice during the Industrial Revolution, as Brian Merchant writes in his outstanding, forthcoming history of the Luddites, Blood in the Machine:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/03/20/love-the-machine/#hate-the-factory

But you don’t have to look back to the stocking frame to find this kind of solidarity. As Hamilton Nolan writes in his newsletter, “Hollywood is the single best example of mature labor power in America”:

https://www.hamiltonnolan.com/p/the-coral-reef-of-humanity-encircling

The entire Hollywood workforce, from grips to carpenters, costumers to plumbers, teamsters to medics, is unionized. That includes writers and actors (I’m a member of IATSE Local 839, AKA The Animation Guild). I live in Burbank, the entertainment industry’s company town (fun fact! The “Hollywood” studios are largely over the city line, in Burbank). Walk down Burbank Boulevard, Magnolia Boulevard, or any of the other major roads, and you’ll pass many union halls.

Burbank is a prosperous place. That’s thanks, in part, to the studios, whose entertainment products are very profitable. But working in a profitable industry is not, in and of itself, a guarantee that you will get a share of those profits. Some of the most profitable industries in the world — e-commerce, fast food, logistics — have the lowest paid workforces.

Burbank is prosperous because the unions made sure that everyone — the grips, the costumers, the animators, the actors, the writers, the teamsters and the pipefitters — gets a decent wage, decent health care and a decent retirement. My pal the set-dresser who worked crazy hours shlepping furniture around sitcom sets for decades? All that work did bad stuff to his joints, which meant that he needed a hip replacement in his forties — which was 100% covered, including his sick leave while he recovered. He was able to take early retirement in his late fifties, with a solid pension, with his health in excellent shape and many years of happiness with his partner stretching before him.

That’s what unions get you: a good job that might be hard at times, and the costs of your work are borne by the employer who profits from your labor. As Nolan writes, the point of unions is to “make sure that people! Are! Not! Disposable!”

Unions deliver the American dream. As Pete Seeger sang in “Talking Union Blues”:

Now, if you want higher wages let me tell you what to do

You got to talk to the workers in the shop with you

You got to build you a union, got to make it strong

But if you all stick together, boys, it won’t be long

You get shorter hours, better working conditions

Vacations with pay. Take your kids to the seashore

http://www.protestsonglyrics.net/Labor_Union_Songs/Talking-Union.phtml

We tend to focus on wages in union discussions, but unions aren’t merely about getting better pay, it’s about making better jobs. When LA teachers went out on strike in 2019, wages weren’t at the top of their list — they bargained for greenspace for every school, replacing rotting portables with permanent buildings, ending ICE entrapment of parents at the school gates, social workers and counselors for schools…and wages.

I really like how Nolan puts this. The way that the studios make money has changed: streaming is clobbering ad-supported TV and movie theater tickets. The studios are adapting. The workers want to adapt, too. The studios would rather “treat[] their work force as a disposable natural resource to be mined, used up, and then abandoned, as business dictates.”

A union gives workers “the same ability to adapt to changing industries that companies already have.” The studios want to leave workers behind. Unions give workers the collective power to say, “No. You’re taking us with you.”

Union workers are wealthier than their non-union counterparts, but that’s not just because of higher wages. As Nolan writes, “Unions make sure that the people get to adapt to changing industries, and not just the investors and the business owners.”

[Union workers] have a far greater ability to build coherent, long-term careers, as opposed to a constant treadmill of unstable short-term gigs. In non-union industries, businesses can just act like ships cutting through a desperate sea of workers, scooping up whoever they want and then tossing them overboard as soon as it’s convenient. In a union industry, though, the companies are forced to deal with the labor force as an equal. The workers have their own damn boat.

Advocates for market capitalism insist that market forces increase prosperity for everyone. They say that, in the end, having corporations serve their shareholders results in corporations serving everyone.

But a comparison of unionized and nonunionized industries reveals the hollowness of that prospect. Hollywood is wildly profitable and it pays every kind of worker well. That’s because workers have solidarity across sectors and trades. Striking writers like jonrog1 are calling on supporters to donate to the Entertainment Community Fund:

https://twitter.com/jonrog1/status/1654168529728307204

The Entertainment Community Fund supports everyone else who is affected by the work-stoppage, all the other creative and craft trades whose work has been halted by the writers’ struggle. If you want to support these workers, make sure you select “Film and TV” from the drop-down menu when you donate (we gave $100):

https://entertainmentcommunity.org/

Because all the workers are in this together. As Adam Conover explains in this amazing CNN clip, David Zazlav, the head of CNN parent-company Warner-Discovery, made a quarter of a billion dollars last year, enough to pay all the demands of all the writers:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aL-YwKO81go

And Carol Lombardini, spokesvillain for the studio cartel AMPTP, told the press that “”Writers are lucky to have term employment.” As John Rogers says, she “wiped out the doubt of every writer who wasn’t sure this negotiation really IS so important, that it actually IS about turning us into gig workers.”

https://twitter.com/jonrog1/status/1654506611086606336

The stakes in this strike are the same as the stakes in every strike: will workers get a fair share of the value their labor creates, or will that value be piled up in the vaults of $250,000,000/year CEOs? It’s not like the studios especially hate writers — like all corporations, they hate all their workers. The same tactics that they’re using to make it so writers can’t pay the rent today will be turned on every other kind of Hollywood worker tomorrow — and when the writers win this one, they’ll support those workers, too.

There’s a lot of concern about AI displacing creative labor, but the only entity that can take away a writer’s wage is a human being, an executive at a studio. As has been the case since the time of the Luddites, the issue isn’t what the machine does, it’s who it does it for and who it does it to.

After all, as Charlie Stross points out, a corporation is just a “Slow AI,” remorselessly paperclip-maximizing its way through the lives and joy of the flesh-and-blood people who constitute its inconvenient gut-flora:

https://media.ccc.de/v/34c3-9270-dude_you_broke_the_future#video&t=3478

Catch me on tour with Red Team Blues in Berkeley, Vancouver, Calgary, Toronto, DC, Gaithersburg, Oxford, Hay, Manchester, Nottingham, London, and Berlin!

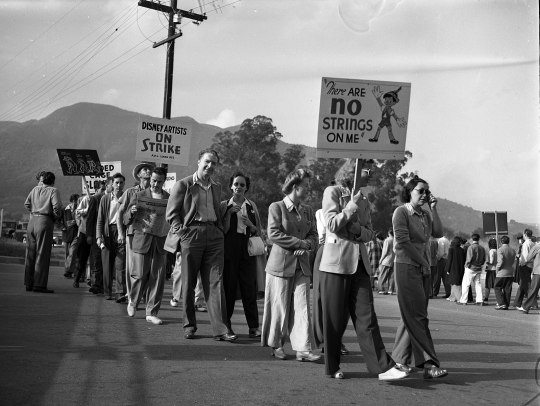

[Image ID: Animators walk the picket-line during the Disney Animator's Strike in 1941.]

Image:

LA Times

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Screen_Cartoonist%27s_Guild_strike_at_Disney.jpg

CC BY 4.0

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.en

262 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mushrooms turn dead wood into food and medicine which is better than anything any tech start up has ever done

#mushies#mushrooms#fungus#fungi#luddites#luddism#funny#funny post#goblincore#gnomecore#gnome post#gnome#wild foods#medicine

51 notes

·

View notes

Note

Where do the Luddites fit in the history of labor organization/protests?

If you want to understand the Luddites, you need to read E.P Thompson, and specifically his Making of the English Working Class.

I'm going to quote the same line from the Preface that everybody quotes, but it really does get at what E.P Thompson was trying to do by writing this book:

"I am seeking to rescue the poor stockinger, the Luddite cropper, the "obsolete" hand-loom weaver, the "utopian" artisan, and even the deluded follower of Joanna Southcott, from the enormous condescension of posterity." (E.P Thompson)

See, thanks to centuries of capitalist (and economist) propaganda, Luddites have been given an extremely bad reputation as backwards fools who blamed technology for their problems and tried to halt the inexorable march of scientific progress. What Thompson lays out in some detail is that the Luddites were striking textile workers who didn't care at all about technology, they cared about the massive wage cuts that were being forced on them by textile employers.

Luddites destroyed machines, not because they feared that the machines would take their jobs, but because the machines were expensive fixed capital and smashing the machines cost their employers a lot of money. Most importantly, Thompson explains that the Luddites only smashed the machines of employers who were pushing for wage cuts - if an employer paid the old wage rates, they left their machines alone.

As to where the Luddites fit into the grand history of labor, I think they represent an example of the sabotage tradition among working-class movements that stretches back to Belgian workers chucking wooden shoes into the gears of capitalism, through to the IWW and their conception of sabotage as industrial direct action against the capitalist system (and god, the backlash that engendered during WWI), through to modern French workers who will wreck power stations to show Macron they mean business.

youtube

So yeah, don't fuck with Ned Ludd if you value your capital.

83 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Luddites

#toot#toots#mastodon#Luddite#Luddites#technology history#technology#workers rights#workers vs capital#workers#labor#skilled labor#labor vs capital#capital vs labor#labor rights#labor movements#labor history

210 notes

·

View notes

Text

52 notes

·

View notes

Quote

A Luddite pedagogy is not about making everyone put away their laptops during class — remember those days? Again, Luddism is not about the machines per se; it's about machines in the hands of capitalists and tyrants — in the case of ed-tech, that's both the corporations and the State, especially ICE and the police. Machines in the hands of a data-driven school administration. Luddism is about a furious demand for justice, about the rights of workers to good working conditions, adequate remuneration, and the possibility of a better tomorrow — and let's include students in our definition of "worker" here as we do call it "school work" after all. A Luddite pedagogy is about agency and urgency and freedom.

'Luddite Sensibilities' and the Future of Education

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

The debate about AI art is the exact same one as the fight the Luddites had about the introduction of weaving machines. Because it's not about the specific technology, it's about worker control over said technology.

The Luddites—skilled weavers themselves—weren't even against the use of those weaving machines in general! But they recognized that, if they weren't the ones in control of the manufacturing, they would be open to exploitation by the factory bosses. And they were right. Now they were being paid for speed—piece work—instead of for their expertise and time. Their wages dropped, they became replaceable, fewer of them were needed to produce as much output, they lost the ability to negotiate for wages and worker protections.

And they were derided for being afraid of progress, afraid of the future, of the power of technology to improve our lives. And that's how they're remembered.

Sound familiar?

The power of capitalism is that it wants to twist anything into its service, including movements against it. The Luddites' movement to protect the value of their labor becomes an insult meaning "scared of technology and science." Artists pushing back against AI art are being called elitists (or Luddites themselves) who just don't want poor people having access to art.

The key, now as in the 19th century, is worker control. NOT "does AI art count as art" (too easy to get derailed into arguments about what art even is), NOT "how do I stop my art from being used in training" (a preventative/reactive measure, not a plan for future action). Framing the argument as an issue that affects all workers builds solidarity, instead of letting us get pitted against each other. No one is free until we're all free, and all that.

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

We're reaching a point where Anti-AI people are becoming more annoying than the Pro-AI bros. Personally, I'd rather draw something than use AI, but some people just see the word "AI" and pretense of being a decent human being leaves their body.

AI is only a product of the real issue, capitalism and how since forever, automation and the idea of removing human workers for the sake of expediency has always been a thing. That's the real problem here.

Going after a person because they used AI for a thumbnail, a comic, or made some Family Guy AI song doesn't achieve anything except making you look like an asshole. You want to protect artists? Go to companies and organizations and make an actual effort to make sure AI trained compositions are ethical. Why not do something to make sure that voice actors are paid and/or compensated if they consent to their voices being used? Why not try to encourage more people to draw without it turning into something rude and giving useful advice?

The answer is they won't do any of this, because it's all reactionary.

The real reason the everyman uses AI is because it's convenient, not because they hate artists or want to replace them. I'm sure there are outliers like that, but people like that exist in everything. The price of living is getting higher and people are broke. Why would someone commission a $50 dollar drawing or sub to a Patreon when they can get an AI composition for $10 maximum? I get it, artists have to eat too, but the issue with AI is rooted deeply into our society and how much we rely on products being cheaper/convenient to use.

The unfortunate truth is that society does not value artists very much, despite how many we have. Animators are infamously underpaid. Being an artist isn't sustainable, and banning AI won't make it so, because again, the issue is with society, mainly capitalistic ones itself. Making copyright stricter doesn't help the average man, but companies like Disney.

If you want to quit art because you feel discouraged by AI, maybe the issue is a lack of internal motivation. Society doesn't give art meaning, you do. It's okay to walk away from things for a bit, or even to quit.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Despite their modern reputation, the original Luddites were neither opposed to technology nor inept at using it. Many were highly skilled machine operators in the textile industry. Nor was the technology they attacked particularly new. Moreover, the idea of smashing machines as a form of industrial protest did not begin or end with them. In truth, the secret of their enduring reputation depends less on what they did than on the name under which they did it. You could say they were good at branding.

The Luddite disturbances started in circumstances at least superficially similar to our own. British working families at the start of the 19th century were enduring economic upheaval and widespread unemployment. A seemingly endless war against Napoleon’s France had brought “the hard pinch of poverty,” wrote Yorkshire historian Frank Peel, to homes “where it had hitherto been a stranger.” Food was scarce and rapidly becoming more costly. Then, on March 11, 1811, in Nottingham, a textile manufacturing center, British troops broke up a crowd of protesters demanding more work and better wages.

That night, angry workers smashed textile machinery in a nearby village. Similar attacks occurred nightly at first, then sporadically, and then in waves, eventually spreading across a 70-mile swath of northern England from Loughborough in the south to Wakefield in the north. Fearing a national movement, the government soon positioned thousands of soldiers to defend factories. Parliament passed a measure to make machine-breaking a capital offense.

But the Luddites were neither as organized nor as dangerous as authorities believed. They set some factories on fire, but mainly they confined themselves to breaking machines. In truth, they inflicted less violence than they encountered. In one of the bloodiest incidents, in April 1812, some 2,000 protesters mobbed a mill near Manchester. The owner ordered his men to fire into the crowd, killing at least 3 and wounding 18. Soldiers killed at least 5 more the next day.

Earlier that month, a crowd of about 150 protesters had exchanged gunfire with the defenders of a mill in Yorkshire, and two Luddites died. Soon, Luddites there retaliated by killing a mill owner, who in the thick of the protests had supposedly boasted that he would ride up to his britches in Luddite blood. Three Luddites were hanged for the murder; other courts, often under political pressure, sent many more to the gallows or to exile in Australia before the last such disturbance, in 1816.

One technology the Luddites commonly attacked was the stocking frame, a knitting machine first developed more than 200 years earlier by an Englishman named William Lee. Right from the start, concern that it would displace traditional hand-knitters had led Queen Elizabeth I to deny Lee a patent. Lee’s invention, with gradual improvements, helped the textile industry grow—and created many new jobs. But labor disputes caused sporadic outbreaks of violent resistance. Episodes of machine-breaking occurred in Britain from the 1760s onward, and in France during the 1789 revolution.

As the Industrial Revolution began, workers naturally worried about being displaced by increasingly efficient machines. But the Luddites themselves “were totally fine with machines,” says Kevin Binfield, editor of the 2004 collection Writings of the Luddites. They confined their attacks to manufacturers who used machines in what they called “a fraudulent and deceitful manner” to get around standard labor practices. “They just wanted machines that made high-quality goods,” says Binfield, “and they wanted these machines to be run by workers who had gone through an apprenticeship and got paid decent wages. Those were their only concerns.”

So if the Luddites weren’t attacking the technological foundations of industry, what made them so frightening to manufacturers? And what makes them so memorable even now? Credit on both counts goes largely to a phantom.

Ned Ludd, also known as Captain, General or even King Ludd, first turned up as part of a Nottingham protest in November 1811, and was soon on the move from one industrial center to the next. This elusive leader clearly inspired the protesters. And his apparent command of unseen armies, drilling by night, also spooked the forces of law and order. Government agents made finding him a consuming goal. In one case, a militiaman reported spotting the dreaded general with “a pike in his hand, like a serjeant’s halbert,” and a face that was a ghostly unnatural white.

In fact, no such person existed. Ludd was a fiction concocted from an incident that supposedly had taken place 22 years earlier in the city of Leicester. According to the story, a young apprentice named Ludd or Ludham was working at a stocking frame when a superior admonished him for knitting too loosely. Ordered to “square his needles,” the enraged apprentice instead grabbed a hammer and flattened the entire mechanism. The story eventually made its way to Nottingham, where protesters turned Ned Ludd into their symbolic leader.

The Luddites, as they soon became known, were dead serious about their protests. But they were also making fun, dispatching officious-sounding letters that began, “Whereas by the Charter”...and ended “Ned Lud’s Office, Sherwood Forest.” Invoking the sly banditry of Nottinghamshire’s own Robin Hood suited their sense of social justice. The taunting, world-turned-upside-down character of their protests also led them to march in women’s clothes as “General Ludd’s wives.”

They did not invent a machine to destroy technology, but they knew how to use one. In Yorkshire, they attacked frames with massive sledgehammers they called “Great Enoch,” after a local blacksmith who had manufactured both the hammers and many of the machines they intended to destroy. “Enoch made them,” they declared, “Enoch shall break them.”

This knack for expressing anger with style and even swagger gave their cause a personality. Luddism stuck in the collective memory because it seemed larger than life. And their timing was right, coming at the start of what the Scottish essayist Thomas Carlyle later called “a mechanical age.”

People of the time recognized all the astonishing new benefits the Industrial Revolution conferred, but they also worried, as Carlyle put it in 1829, that technology was causing a “mighty change” in their “modes of thought and feeling. Men are grown mechanical in head and in heart, as well as in hand.” Over time, worry about that kind of change led people to transform the original Luddites into the heroic defenders of a pretechnological way of life. “The indignation of nineteenth-century producers,” the historian Edward Tenner has written, “has yielded to “the irritation of late-twentieth-century consumers.”

The original Luddites lived in an era of “reassuringly clear-cut targets—machines one could still destroy with a sledgehammer,” Loyola’s Jones writes in his 2006 book Against Technology, making them easy to romanticize. By contrast, our technology is as nebulous as “the cloud,” that Web-based limbo where our digital thoughts increasingly go to spend eternity. It’s as liquid as the chemical contaminants our infants suck down with their mothers’ milk and as ubiquitous as the genetically modified crops in our gas tanks and on our dinner plates. Technology is everywhere, knows all our thoughts and, in the words of the technology utopian Kevin Kelly, is even “a divine phenomenon that is a reflection of God.” Who are we to resist?

The original Luddites would answer that we are human. Getting past the myth and seeing their protest more clearly is a reminder that it’s possible to live well with technology—but only if we continually question the ways it shapes our lives. It’s about small things, like now and then cutting the cord, shutting down the smartphone and going out for a walk. But it needs to be about big things, too, like standing up against technologies that put money or convenience above other human values. If we don’t want to become, as Carlyle warned, “mechanical in head and in heart,” it may help, every now and then, to ask which of our modern machines General and Eliza Ludd would choose to break. And which they would use to break them.

#history#labour#employment#capitalism#exploitation#technology#textiles#folklore#industrial revolution#luddites#britain#england#ned ludd#william lee#thomas carlyle#elizabeth i#weaving#knitting#stocking frame

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today, the label luddite is an epithet for someone afraid of technology and the change it can bring. Merchant’s book makes clear that Luddites did not fear automation in the sense of being afraid of the machines or longing for an idyllic past. On the contrary, as Merchant points out, clothworkers were often themselves intimately engaged in improving the technology they used. Some of them proposed paying for job retraining by taxing factory owners who implemented the automating machines, earning the workers the title of “some of the earliest policy futurists,” according to Merchant. These efforts—to use official channels at the local and parliamentary levels—failed, however. With their futures rapidly foreclosing, the clothworkers invoked the fictional Ned Ludd (alternatively, Ludlam), an apprentice stocking-frame knitter in the late 1700s who, the story went, responded to his master whipping him by destroying the machine. Inspired by his act of sabotage against a cruel employer, the Luddites campaigned to halt the spread of the “obnoxious machines.” Soon factory owners found threatening letters signed by Captain Ludd or General Ludd or King Ludd. The letters also allude to another hero of working people from Nottingham, Robin Hood. Merchant argues that the mutability of Ned Ludd served as an organizing symbol akin to a playful but potent meme.

[...]

The Luddites used the tools at their disposal and did so through collective action. Merchant details the day-to-day organizing efforts of the movement’s leaders. We are ushered into a clandestine world of codes and oaths, of backroom meetings and nighttime training. The scheming makes for entertaining reading. But beneath the private planning and public sabotage lurks a more lasting lesson: movements to dismantle automation’s physical infrastructure often depend on building relational infrastructure. Tight-knit communities are extraordinarily important here: they buffered the Luddites from harm and fostered creative thinking rather than merely alienation among adherents and their allies. Increasingly finding themselves wrung out by those in power, these communities coalesced around shared causes that overlooked intragroup differences. This opened space for women, Merchant tells us, to claim the nom de guerre Lady Ludd and charge into markets to demand fair food prices from shop owners and food suppliers. It worked. The “auto-reductions,” as they were called, demonstrate the power of people working together to force change. Similarly, resistance to automation can be creative and provide openings to bring myriad others into the tent.

74 notes

·

View notes

Link

If sf asks, “what if the machine had a different social arrangement?” then steampunk asks, “what would it be like if we could have the productive benefits of machines without their regimentation?”

A craft worker enjoys enormous autonomy. If they get a cramp or need a bathroom break, they can just stop. If they’re hungry, they can eat. If the landscape outside the window is looking especially picturesque, they can stop and contemplate it, or even step out into the fresh air to enjoy it.

Even the most labor-friendly, cooperatively owned assembly line can’t function if its workers do their own thing. The price of factory efficiency is autonomy: a worker in a multi-stage process has other workers upstream and downstream depending on them to maintain the pace and regimentation of the line.

Steampunk is fantasy in that it imagines lone craftspeople working with all the autonomy of the individual mad scientist inventor or tinkerer, but producing goods characteristic of the factories where workers had to check their autonomy at the door.

That’s a utopian vision, one that was especially enticing in the 2000s, when internet collaboration tools allowed thousands of strangers to engage in large, collective endeavors, like writing an encylopedia or an operating system, without any bosses, working at their own pace, relying on version control systems and wiki pages to coordinate their labor while they worked their tools in their crafters’ cottages all over the world.

-Gig Work Is the Opposite of Steampunk

#chickenized reverse-centaurs#arise#chickenization#reverse centaurs#large firm wage premium#magpie killjoy#brian merchant#blood in the machine#steampunk magazine#love the machine hate the factory#luddites#labor#steampunk

92 notes

·

View notes

Note

what is your critique of historical luddism?

ok to be clear i don't mean that they like, did something morally objectionable lol. but i think both the 'classic' narrative here ("haha, silly people resisting technology!") and the revisionist one ("actually they were objecting to the way factory owners used new technologies to squeeze workers and pay them less") have failed to convey the specificity of the luddites' economic position and critique. these were 'skilled' workers who were not trying to spearhead some kind of broader workers' movement; they wanted to preserve their own position, and to continue being designated as respected labourers who should be paid more and treated better than the 'unskilled' or purely manual labourers. so, smashing machines made sense for the luddites because mechanisation was a direct threat to their position as the people who were trained to perform their specific, relatively high-stature work in the textile industry. it was never a broader position about how machines should or shouldn't be used in manufacturing, or production more generally; they were not challenging the logic of wage labour but trying to preserve their own favourable position in this system. in general mechanisation is of course not inherently counter to workers' interests---like, if we can save ourselves certain work and produce more efficiently, this can be a good thing! this discussion obviously needs to be nuanced by questions like: how are the machines themselves produced, what materials are required, how does any process of mechanisation fit into processes of colonial and imperial exploitation, &c &c. so my position here is not an uncritically pro-machine one either lol. but the luddites are such a limited case and one that was never really aiming to answer such questions or even pose them. they're better understood as a case study in how skilled workers (some of whom had ownership stake in their own firms/machinery!) may end up trying to uphold the system of their own exploitation if they perceive their position within it as favourable enough.

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

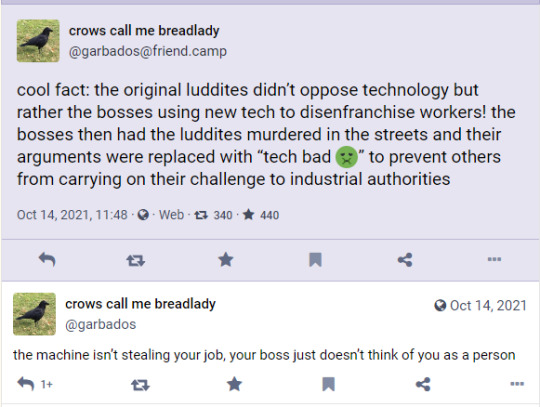

the machine isn’t stealing your job, your boss just doesn’t think of you as a person

https://friend.camp/@garbados/107100669666852190

#toot#toots#mastodon#Luddites#means of production#work#labor vs capital#capital vs labor#labor rights#skilled labor#labor movement#labor movements#labor#workers rights#workers vs capital#workers

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

There is no way to make a legal distinction between "AI" and other image generation technology. Any legislation which could be passed to put restrictions on AI art would have to be written in a way that would roll back Fair Use protections. Please please grasp this simple concept I'm so tired of explaining it to supposedly anti-capitalist mutuals. The fact that these laws even have a CHANCE of passing should have been your first clue that none of this will be designed to benefit you.

4 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Can you then wonder, that in times like these, when bankruptcy, convicted fraud, and imputed felony, are found in a station not far beneath that of your Lordships, the lowest, though once most useful portion of the people, should forget their duty in their distresses, and become only less guilty than one of their representatives?

Lord Byron Defends the Luddites in his Maiden Speech in the House of Lords : History of Information

3 notes

·

View notes