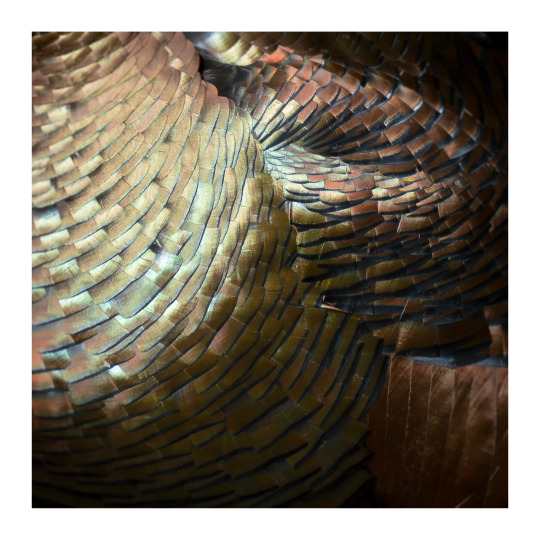

#Meleagris gallopavo mexicana

Text

Plumas brillantes.

Iridescent plumage on Gould’s turkeys / guajolote norteño (Meleagris gallopavo mexicana) at Santa Rita Lodge. In Madera Canyon, Santa Cruz County, Arizona.

#photographers on tumblr#Gould's turkey#Meleagris gallopavo mexicana#abstraction in nature#turkey feathers#iridescence#Santa Rita Lodge#Madera Canyon#Santa Cruz County#Arizona

1K notes

·

View notes

Video

Tipos de guajolote y como elegir una buena guajolota.

Para pequeños proyectos los mejores guajolotes son las que están en las comunidades el medio rural, estas guajolotes “Criollas” se han adaptado durante siglos al clima, al manejo y a la alimentación, es necesario comprar guajolotes en crecimiento o huevos para incubarlos. Una alternativa seria con algunas guajolotes criollas e ir tomando experiencia en la incubación natural o artificial de huevos para de ahí mismo surtirse de los guajolotes que se requieren para sustituir a los guajolotes viejos e ir repoblando la parvada de guajolotes ponedoras.

La raza más utilizada e ideal para este tipo de producción es la raza Melleagris gallopavo mexicana, como su nombre lo indica es originaria de México y es una subespecie del pavo salvaje común (Meleagris gallopavo), especie que aún vive en los bosques de América del Norte.

Cantaro, H., Sánchez, J., & Sepúlveda, P. (2010). Cría y engorde de pavos. Instituto Nacional de tecnología Agropecuaria, INTA. Argentina. 30p.

0 notes

Text

Where the Wild Turkeys Are

November 20th, 2017|Tags: Holidays, wildlife|0 Comments

.fusion-fullwidth-1 { padding-left: px !important; padding-right: px !important; }

By Dylan Stuntz, American Forests

This Thanksgiving, you might find turkey on your plate, but it generally isn’t of the wild variety. On the contrary, wild turkeys are found in forests across the country — 49 states, to be exact! Five subspecies are scattered throughout the continental U.S. and Hawaiʻi, indicating the turkey’s ability to live in a variety of forest ecosystems, from swamps to oak forests to deep desert.

A female eastern wild turkey in Canada. Credit: Dave Doe

Turkeys’ preferred habitat is mixed-conifer and hardwood forests, with various open spaces to find food, such as seeds, nuts, leaves and insects. Despite their large size, they are agile fliers and capable of roosting among high trees, either while foraging for food or avoiding predators.

Each subspecies prefers a unique habitat and possesses slightly different plumage, but they are all considered to be members of the same species of wild turkey (Meleagris gallopavo).

Eastern wild turkey

(Meleagris gallopavo silvestris)

Christened “forest turkey” by the Puritans in the 1800s, this turkey has the largest range of any subspecies. They can be found in much of the eastern U.S., spanning from the Canadian border to northern Florida and westward to the Mississippi River. They can be identified by the brown-tipped upper tail feather found on the male. Habitat for this subspecies is typically wet, swampy land, or early-growth forests with low-lying brush situated throughout.

Osceola wild turkey

(Meleagris gallopavo osceola)

This subspecies can only be found in southern Florida. The smallest subspecies of wild turkey, this bird has darker, green-tinged feathers and can be found among palmetto stands and swamps. Researchers estimate that 80,000 to 100,000 birds make up the population, but an accurate count is difficult to make because the bird’s swampy habitat isn’t very accessible to researchers.

Rio Grande wild turkey

(Meleagris gallopavo intermedia)

Found among the southern/central desert regions of the U.S. this bird was also introduced and has found a niche in northern California and Hawaiʻi. Out of the five subspecies, this one has the longest legs, which are best adapted to prairie living. The Rio Grande wild turkey can usually be found among scrub oak, mesquite and pine forests, as well as along streams and river bottoms.

Merriam’s wild turkey

(Meleagris gallopavo merriami)

These turkeys are native to the Rocky Mountains, clustering among forests of ponderosa pine. The back feathers of this subspecies are white-tipped. During the winter months, the turkeys will move down the mountain slopes to avoid snow, then return during the spring to feast on dropped seeds. The turkey was named after C. Hart Merriam, first chief of the Division of Economic Ornithology and Mammalogy of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, a division that would later become the National Wildlife Research Center and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Gould’s wild turkey

(Meleagris gallopavo mexicana)

The largest of the subspecies, this turkey can only be found in Arizona, New Mexico and northern Mexico. Its feathers are copper-colored with a greenish tint. They frequent small underbrush, commonly found along dry creek beds. While this turkey inhabits a dryer climate than the other subspecies, it manages to subsist on a diet of insects, berries and seeds, scavenging wherever possible.

While each of these varieties of turkey may have slightly different habitat, one thing remains constant: To support a wild turkey population, the landscape needs to have vegetation. Turkeys co-exist with trees and forests all across the country, whether it be roosting in them, feasting on them or simply living among them.

The post Where the Wild Turkeys Are appeared first on American Forests.

from American Forests http://www.americanforests.org/blog/where-the-wild-turkeys-are/

0 notes

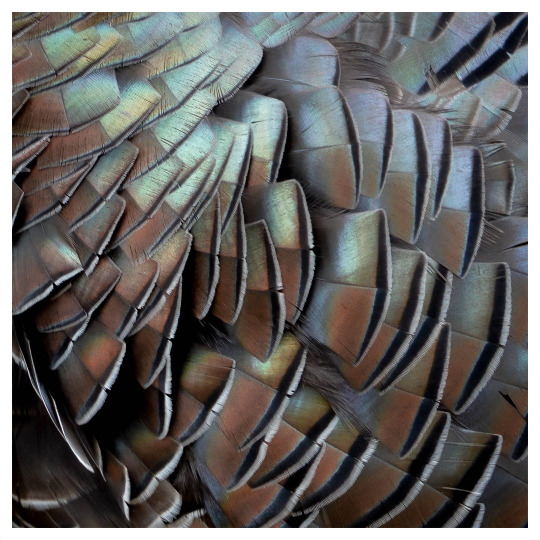

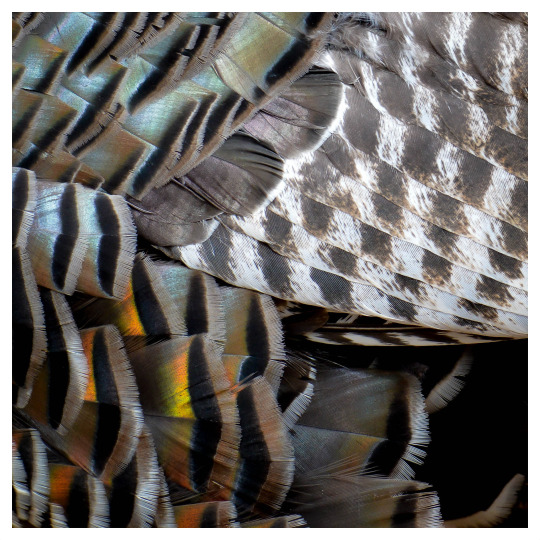

Photo

Plumas de pavo.

Feather details of Mexican (Gould’s) wild turkeys (Meleagris gallopavo mexicana), at Ash Canyon.

Please click any photo in the set for enlarged views.

#photographers on tumblr#birds#Gould's wild turkey#Meleagris gallopavo mexicana#abstraction in nature#Ash Canyon Bird Sanctuary#Southeastern Arizona Bird Observatory#Cochise County#Arizona

3K notes

·

View notes

Photo

¡Pavo Rey!

Gould’s turkey / guajolote norteño (Meleagris gallopavo mexicana), at Ash Canyon Bird Sanctuary, Cochise County, Arizona.

Please click photo for an enlarged view.

#photograpehrs on tumblr#bird#Gould's turkey#Meleagris gallopavo mexicana#thanks for the caption Dave!#Ash Canyon Bird Sanctuary#Southeastern Arizona Bird Observatory#Cochise County#Arizona

98 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mexican (Gould’s) turkeys (Meleagris gallopavo mexicana) at Ash Canyon.

These birds are part of a flock of about twenty turkeys that are wintering in the canyon. They are the largest subspecies of wild turkeys in the United States, with striking long legs and vivid feather coloration. It is also the turkey subspecies with the fewest numbers. The birds were entirely extirpated in their historic range in the U.S., subject to overhunting by early pioneers. In the 1990s the Arizona Game and Fish Department and U.S. Forest Service released 35 wild turkeys from Mexico into their former habitat, and a population of about 1200 birds is now established in montane areas of southern Arizona and New Mexico.

Like many birds in the U.S., this turkey is stuck with a name that honors an ODWG (Old Dead White Guy), John Gould, recognized mainly as a skilled taxidermist and illustrator, and as a friend of explorer-naturalists like Darwin. He certainly never saw one of these birds in the wild. Because representation and diversity matter, I support removal of eponymous bird names, and renaming with descriptive terms. My proposal for this bird is the Chiricahua turkey, for the sky island mountain range here in southeastern Arizona. The mountain range itself is named using the Opata word for wild turkey, and offers a clear cultural and geographical link to these marvelous animals.

#photographers on tumblr#Mexican turkey#Gould's turkey#bird#bird names#Meleagris gallopavo mexicana#renaming birds#Ash Canyon Bird Sanctuary#Southeastern Arizona Bird Observatory#Cochise County#Arizona

282 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Tom turkey confronting his arch rival, the Honda Fit.

Turkeys evolved during the early Miocene epoch, about 20 mya, but it’s only in the last few hundred years they have had to contend with their own reflections in manmade objects. No wonder they want to peck them to death.

Gould’s turkey / guajolote norteño (Meleagris gallopavo mexicana), at Ash Canyon Bird Sanctuary, Cochise County, Arizona.

#photographers on tumblr#Gould's turkey#Meleagris gallopavo mexicana#reflection#Ash Canyon Bird Sanctuary#Southeastern Arizona Bird Observatory#Cochise County#Arizona

95 notes

·

View notes