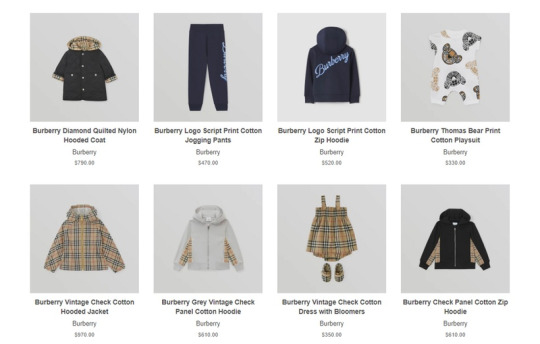

#Nordstrom

Text

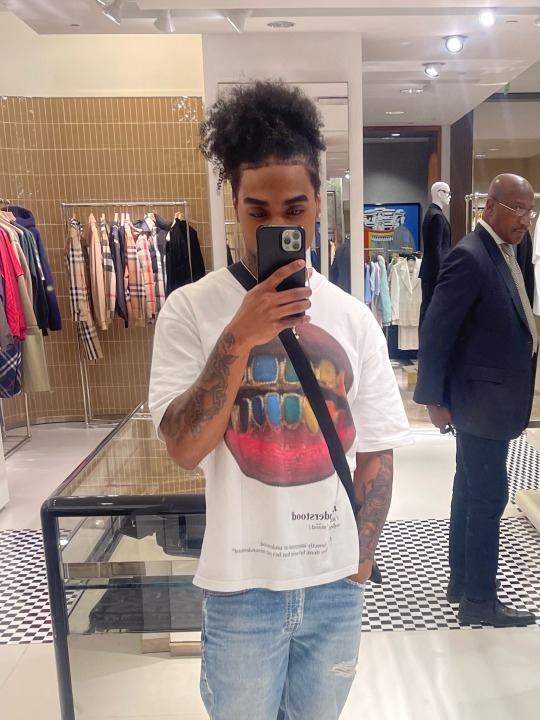

Can I help you?? 🌚

134 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Everett Williams for Nordstrom

https://www.instagram.com/everettwilliams/

38 notes

·

View notes

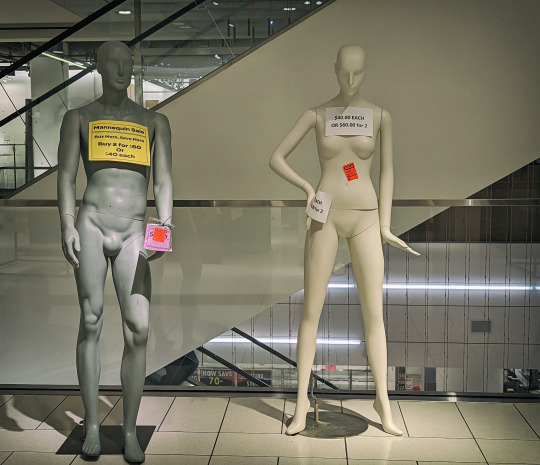

Text

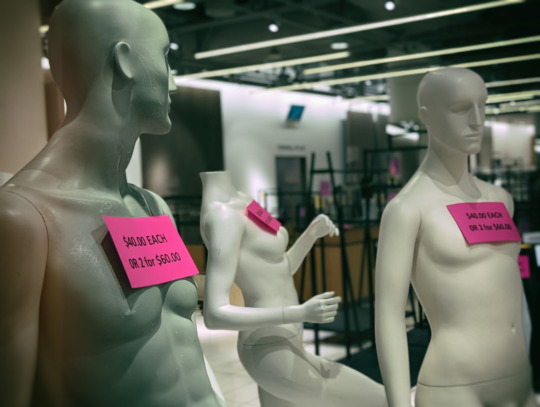

Just one look, that's all it took…

#mannequin#for sale#department store#nordstrom#vancouver#photographers on tumblr#original photography on tumblr

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Scarlett Johansson attending The Outset x Nordstrom event today in NYC

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

slingback sandals by jeffrey campbell

#diamondsandcigarette#2014 tumblr#girlblogger#coquette#girlblogging#model aesthetic#pink pilates princess#soft aesthetic#slingback heels#jeffrey campbell#nordstrom

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

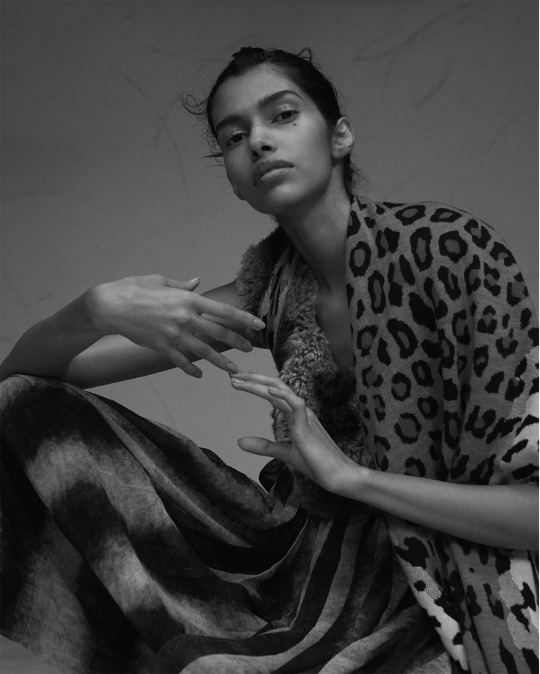

Pooja Mor for Nordstrom

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Design from Scotch and Soda, photographed for Nordstrom Spring-Summer 2023

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today has been a good day. I went out with my sister to go shopping for outfits for my friend’s wedding next month. First we stopped at Nordstrom Rack and tried on lots of dresses. I found one I liked that looked good on me and fit well, and it wasn’t as expensive as I was expecting!

After that we went to Quaker Bridge Mall. We started at Macy’s Backstage, where I got these shoes to go with the dress.

The silver looks a little dark in the picture I took. It’s brighter and sparklier in person.

There weren’t any fancy enough dresses in Backstage, so next we checked out the regular part of Macy’s. We tried on some more dresses with no luck. Next was Torrid, nothing there fancy enough. Then we went to JC Penney and tried on a bunch more dresses. My sister ended up getting a gorgeous silver glittery dress. This photo doesn’t do it justice.

After we had pizza in the food court we went to Victoria’s Secret because I had a bunch of coupons. Plus, I wanted to buy something on my VS credit card to keep it open since I haven’t used it since early last year. I ended up splurging and getting a new perfume, the new Bombshell Escape. It has a beautiful, light tropical scent.

On the way out of the mall we stopped at Torrid again to pick up some Spanx. So now we are all set for next month!

The day still has many hours in it and I am POOPED! It was a really nice day, though. :)

#sister#sister time#Nordstrom rack#nordstrom#dresses#dress shopping#shopping#shoes#Macy’s backstage#Macy’s#torrid#jc penney#victoria’s secret#perfume#bombshell escape#bombshell#spanx#family#personal

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Draculaura's black shorts in "Monster High 2"!

Exact: Faux-Ever Leather Pleated Shorts (Nordstrom)

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Poverty and Comfort

Taken from, and funded by, my Patreon. Please check it out.

It’s happening again.

I just got forced back a place in line, mere seconds from being served. Another patron, presumptive and impatient, slid between me and the server working the till in a move that I would describe as all too practised, as smooth, to ask what soup flavours were available. This patron, surfacing from nowhere like a submarine, came up on my starboard side. She cut in, pitched her question across the counter, then cast a glance my way and, to use a phrase my mother would, “looked at me like I was shit on her shoe.”

While I’m not exactly shuffling about in my tracksuit bottoms today, there’s nothing special about what I’ve chosen to wear. I should perhaps have picked The Other Coat, which has magically caused several strangers here to strike up conversations with me. In particular, I feel it’s no small deal for a young woman to decide to start talking to a man she doesn’t know, but one day I was suddenly being told that I am classy and refined, being English and so smartly dressed. Perhaps on a different day I might have felt flattered, but I felt more like some sort of fraud was being committed. I was wearing class camouflage.

It’s something I try to do here, in my local fancy café, because otherwise I feel uncomfortable. But I realise that it’s also something I’ve unconsciously done for so much of my life.

I’ve got a few things that I want to write about here today, everything from sandwiches to suits to submarines, but before I go on I have to ask: Do you know that phrase “like I was shit on her shoe”? Do people say that where you’re from? Some of my lexicon is loaned from Chiswick and Southall, passed down from people who worked as labourers and long-suffering housewives, from bricklayers or from the lower decks of the Royal Navy, from homes that had no hot water and outside toilets. It’s the sort of language muttered past cigarettes on brick stairwells, or yelled across loading docks embellished with incoherent graffiti.

Sometimes these things slip out of me and no-one has any idea what I’m talking about. I make a right pig’s ear of it. And in those moments I’m suddenly somewhere else. I’m in a different time, a different place. And a different income bracket.

Or perhaps the different income bracket is where I am now. So in which do I really belong? Tell me, which would you associate me with? Graffiti and slang? Or poise and politeness?

It’s a question we can return to, if you want, because this piece of writing is in part about returning to things. When I began drafting it, months ago now, I didn’t realise just how much it echoed something I had written nine years before. I was already trying to articulate trends and patterns, without realising I had fallen into one myself.

For now, I have a different question. Did you know that one of Vancouver’s most infamous shortcuts has just closed? The three story, two hundred and twenty thousand square foot Nordstrom store that sits right between the city’s central plaza and two of its busiest stations is no more. Vancouverites will no longer be able to use it to pass diagonally through a whole block, as the crow flies, weaving dreamily amongst racks of designer handbags and thousand dollar flip-flops, before finally returning from this fantasy realm like Dante stumbling out from the underworld.

It’s a shortcut I’ve taken hundreds of times. Sometimes I would stop to inspect a shoe, or to check the price on a tie. The shoe would be upward of seven hundred dollars. The last tie I looked at was one hundred and eighty.

This Nordstrom had its own coffee shop, restaurant and even a cocktail bar. Curiously, its drinks were no more expensive than any other café nearby and, as I began drafting this in the early spring, I stopped for a drink on my way through. I asked the person serving me about her Totoro tattoo and she beamed. “Nobody who shops here recognises Totoro,” she said, and began talking about her clientele. They don’t have that kind of thing on their minds, she said.

She told me that the stations serving drinks were closing within a week and that she didn’t know if she’d have a job after that. “They’ll probably put us on the shop floor with everyone else at minimum wage.” Her colleague, selling suits that ranged from fifteen hundred dollars to eight thousand, told me he didn’t know when his last day of work would be, nor what kind of severance package anyone would have. Apparently, more than six hundred staff didn’t know when their jobs would end, but if Nordstrom did know one thing it was that it certainly wasn’t making enough money in Canada, with its thousand dollar flip-flops sold by minimum wage staff. It was time for the retailer to skedaddle.

I like talking to working people. Often, the conversations are more grounded than the kind of armchair politics you can abruptly find yourself enmeshed in at a house party, trapped suddenly in a kitchen surrounded by revellers armed with dangerously articulated glasses of wine.

The suit-seller had to go. He was run off his feet. Nearby, a rack of torn, pre-ripped jeans was on sale for three hundred dollars, more than seven times what I paid for my pristine pair. They were hung within grasping distance of some thousand dollar dresses.

I’m not an expert on dresses, but the thing about many of those seven hundred dollar shoes, those thousand dollar flip-flops, is that they were shit. They looked absolutely terrible.

Nordstrom allowed an aimless Dante, momentarily directionless in this realm, to sip their coffee and watch people buying their branded shoes and bags and clothes, and to try and perform some mental mathematics. It was a strange experience, because the conclusions you would reach would be that some of the school-age people buying things here were far too young to be able to earn the sums of money they were spending, whilst others were obviously spending many thousands as they bought items for themselves and others, nevertheless gliding through this experience with the casual indifference of a sleepwalker fumbling through a fridge.

Back in my local fancy café they are advertising for staff and perhaps they can take on one or two of the Nordstrom exodus. I look up the posting and wages start at fifteen dollars sixty-five an hour, which I confirm is the minimum wage in British Columbia. Once again, the coffee here costs about the same as anywhere else nearby, but everything else is expensive. The sandwiches are at least double.

And many of those sandwiches don’t look very good.

The staff here often talk to me. They say they talk to me not because of The Other Coat, but because I’m The Englishman Who Tips. It turns out, they tell me, that a majority of their customers do not tip. Most of these staff are smiling young women with accents from France and Romania and Peru. They are always smiling and they are always on their feet and they are always outnumbered by customers who want things and who will not hesitate to slide into a line with practised skill. They are dressed head to toe in white uniforms, but sometimes their footwear gives them away. They are not wearing thousand dollar flip-flops, or any of the sort of things that their customers are. They are much less affluent or, as we bluntly say where I am from, they are poorer.

I worked about five years of retail when I was a smiling young man and much of it was at or around the minimum wage. There were a lot of customers who wanted things and more than a few slid into lines at the till in manoeuvres that seemed all too practised. I’ve said this before, but I’ll say it here again, because it bears repeating: One of the places I worked was a flagship store that made over twenty million pounds a year, a figure that the Bank of England Inflation Calculator tells me is equivalent to thirty-six point seven five million today, more than three million a month. We’d have these weekly briefings where the managers would urge us to work as hard as possible to help make those numbers as big as possible.

Later, when the Labour party came into power, the minimum wage bumped up to three pounds twenty an hour for young adults. But I wasn’t yet an adult and so that rate did not apply to me.

The great thing about young people is that you can make them do exactly the same things as older people, but pay them much worse. Because young people aren’t as important, are they? They’re not as worthy.

Sometimes these retail roles were very cold. Sometimes they were very hot. Whatever the weather, those customers would surface out of nowhere like submarines. They would glide, as if lubricated by their money, but I suppose money always has been something that helps you grease your way through life. I’m certainly slipperier these days. Occasionally I will glide over problems that might have punctured the Paul of the past. I throw money at stuff like a wizard casting a spell and it just goes away.

When I caught sight of the shoes worn by one staff member in The Fancy Café I was suddenly hurled back through time to my years in retail, and a hundred and one experiences came back to me in the blink of an eye. I still have many, many memories of how customers treat retail and service staff, because when a stranger treats you in an extraordinary and unexpected way, it tends to stay with you. I remember one furious man saying “I pay your wages,” which was not true, because Kingfisher plc paid my wages, but he really believed his money and his transactions gave him entitlements and that this was how you spoke to a sixteen-year-old service worker.

It’s been a hot minute since I was sixteen, but I still react to a nearby “Excuse me” with the assumption that someone must want something.

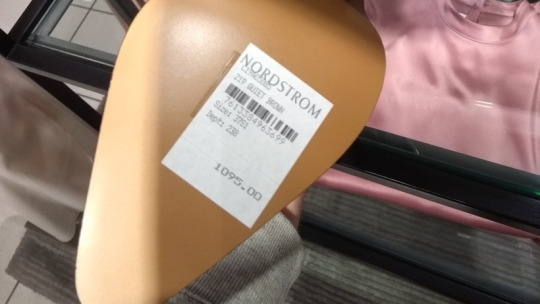

Nordstrom is all gone now. While I was drafting and redrafting all this, it gradually emptied the last of its inventory, first discounting its shoes and its suits and its ludicrously expensive tableware, before then going on to sell even its fittings and its fixtures. Nordstrom offered you the chance to buy a greasy, scratched glass table for a thousand dollars, for some shelves for four times that. Realising that this may sound unbelievable, I took a picture.

Around the same time, I talked to a friend about Nordstrom and, by coincidence, discovered that they used to work in one in the US. “Nordstrom deserves to close,” they said. “If you don’t make enough via commission, they pay you minimum wage. But you get a warning. You can only do that three times before they fire you. What’s worse, they have a lifetime return policy, no questions asked. If a customer returns an item within a year of purchase, it comes back out of your commission, because ‘if you did your job as a salesperson right, they’ll love it so much they won’t ever return it.’”

“I sold this guy nine hundred dollars of stuff for his daughter for Christmas and I didn’t want to because he had no idea what she wanted. Months later my paycheck was docked because she returned everything.”

Well, it has closed now, but I still wonder about those six hundred staff, much as I wonder if it will be replaced by anything kinder. I think about working a job like that, and how only a handful of circumstances or coincidences separate me from being in that position.

But why should I wonder, and why should I worry? These days, I have the class camouflage. I have the fancy coat, or the ability to speak properly and, provided I don’t accidentally let loose a school story of how one of our teachers was stabbed or talk about bored classmates crashing cars for fun, I can avoid too many strange stares from the people around me. I could pick up one of those thousand dollar flip-flops in Nordstrom and nobody acts like I shouldn’t be there, contemplating two shitty, stuck-together pieces of plastic that I could take to the checkout and buy from someone who would have to work at least sixty-four hours to be able to afford them, a length of time I doubt those flip-flops would even last.

Yeah. Why should I worry?

But these days I can’t avoid the slow swell of something I’m increasingly feeling, a kind of growing gravity that has been tugging at me from my past. These last few months it’s given me a kind of emotional whiplash, as I’m pulled in every direction by currents and collisions, by connections in my personal life, by events in the news, by conversations I share with my therapist on lamplit evenings in those generic and inoffensive spaces made from featureless pictures and neutral colours. Even by my own writing pulling the stitching out of the past as it heals, closes up and knits itself together behind me. Because when I press on the place that it was, I can still feel the contours.

All this pulling and tugging has made for an uncomfortable ride. I haven’t had enough high-g training. Usually when you’re in situations where you’ll be experiencing sharp and sudden manoeuvres there are ways to prepare you, to toughen you up. Pilots and astronauts are put in specialist equipment or precisely-engineered simulators that spin them around and shake them about until they no longer flinch or vomit or pass out. The rest of us have to hold on and hope for the best.

Here’s the thing: much of the last year has been very comfortable for me. Work has been terrific. I travelled to the United States for the first time since 2019, and then again, and then again. I was able to put money into a pension for the first time in more than a decade. I bought myself new things. I made plans for a future that could be more open than ever.

And two of the strongest feelings that I have in reaction to this are guilt and confusion. I am fidgeting awkwardly in that wrong income bracket, in the wrong tax bracket. I redraft this now in the local fancy café, surrounded by people wearing capital B Brands and carrying designer bags, designer scarves, designer hats, even wearing elaborate designer watches, because they have decided they need to spend thousands of dollars to have a second way to tell the time.

I don’t come here to write so much because I choose to be in the fancy café, but simply because it is near and it is open late and it has the most space and the least clamour. There are other places I would prefer to be, but some of those don’t exist any more, others have been pushed too far away. I don’t have much choice.

You see, the wealth that leaks from the fashionable, expensive shops downtown, right where that Nordstrom used to be, has been slowly rolling downhill toward my historically more modest neighbourhood. Like molten gold, it bubbles toward us, gentrifying everything it touches. I see it in the shops and stores that have opened after the peak of the pandemic, replacing the businesses that couldn’t survive. That which regrows is better, because it is more expensive, more exclusive. And I see the same change bubbling through the people on the pavement, the cars parked in the streets, even the photoshoot faces on dating apps.

Bubble, bubble. It’s like the rising tides of climate change.

There used to be a burrito place on the corner that would sell you your dinner for seven dollars. Now it’s a store selling designer clothes for babies. One toddler’s jacket is nine hundred and seventy dollars. Before tax.

Your child will grow out of that in six months.

Back in the spring, some time between my many Nordstrom shortcuts, I went to a party in my apartment building for its longest-serving resident. After forty-five years, this woman in her mid eighties was moving to an assisted living residence. Many people from my building’s ninety apartments turned up, including some who have lived here for decades. Without prompting, several talked about how they could never afford to move out, since the province’s rent caps mean existing residents only have to weather a very gradual increase in rates. This doesn’t apply to signing a new lease somewhere else, and so new people moving into our own building are paying at least a thousand dollars more a month than when I first arrived, and even more than other, longer-term residents. We are all sat tight on islands of safety amongst ever-rising tides. We have become surrounded in our stubbornness.

Around the corner from me, a four hundred and thirty square foot one-bedroom apartment is being rented out for a fairly typical two thousand, six hundred and ninety dollars a month. That’s over thirty two thousand dollars a year. Various contemporary census reports list the median income in my neighbourhood as being between fifty and fifty-five thousand dollars a year, before tax. Someone earning that much would be spending sixty percent of their income just to rent such an home.

I would say that this feels uncomfortably familiar, but a decade ago I was spending maybe three quarters or more of my earnings to cover my rent. And a decade ago I was starting to write something just like this, once again surrounded by notes and drafts that I hoped to shape into something not just coherent, but that people would understand.

And once again I remember what it’s like not to have money.

Those rent caps aren’t protecting us from the ever rising price of everything else. I go shopping, see a pack of bagels apparently price frozen at three dollars and remember when it cost almost half this. It wasn’t long ago, it wasn’t some childhood memory, it was less than two years past. The other week, two dollars were suddenly added to the price of yoghurt. Cereal costs a third more. The cheapest bar of budget chocolate suddenly became fifty percent more expensive. This isn’t happening to luxury brands or inessential items, but staples and budget foods. You can watch it happen almost in real time, like accelerated footage of shoots sprouting or plants budding in the spring.

Wait a second, was I saying this a decade ago, in another country, in another time?

It’s happening again.

I just got forced back a place in line, mere seconds from being served. Another patron, presumptive and impatient, slid between me and the coffee I ordered, snatching it away in a move that I would describe as all too practised, as smooth. They had ordered the same drink as me, after me, and presumably it had never crossed their mind that someone else, stepping up to the counter, could possibly come before them. They make no eye contact. Indeed, they don’t even acknowledge my existence. I’m just some slightly scruffy guy in a New England gallery, probably someone who shouldn’t really be here enjoying art, and I’m not nearly as well-dressed, as well-decked, as they are.

I don’t know if it’s my imagination or not, but sometimes I wonder if, in my scruffier manifestations, I become invisible, inconsequential.

I remember a lot of strange stuff these days. Some people say that the Coronavirus pandemic played havoc with our memories, our restriction and isolation turning our minds inward and having them engage in an odd kind of archaeology. I’ve remembered old friendships, old journeys, old habits. And lately I’ve remembered folded broadsheets on kitchen tables in richer friend’s houses, with the features they carried and the writers who wrote them. I’ve remembered the economic downturn of 2008 and how one broadsheet ran a feature where “We Asked 100 People how they’re Coping with the Credit Crunch” and how what this really seemed to have done was ask one hundred people who were antique shopping in Islington how they had cut back on au pairs and skiing holidays. I’ve remembered how this was when I first noticed the peculiar distance from which such newspapers would observe and report on people who lived on lower incomes, who were poorer, occasionally letting one of them grace their pages with authentic stories of jobsearching and social housing.

Poverty was talked about as if it was some curious other country. It existed somewhere else.

I think I remember this in part because news reporting in the pandemic followed the same patterns the same way a little music box quickly repeats the same cutesy tune. Poorer people, it turned out, were feeling the effects of the pandemic much more, said the reports, officially marking such as observation as news, as if poorer people hadn’t felt the effects of everything else much more, since the god damn start of recorded fucking history.

Or maybe I remember it because, as spring began, a CBC News report on a (the?) housing crisis described the state of some poorer people’s living states as shocking, as if it was new, novel, never before seen. And yet such things can only truly shock someone who has gone through life unaware that some of the human beings around them have much less. I was not shocked by any of the things depicted in that report, much as I am never shocked to learn that someone has mould on their walls, broken windows, dangerous appliances, leaking plumbing, freezing bedrooms, failing electrics, collapsing walls or some sort of exploitative landlord or manager (nor that these things make you sick). I am only shocked that there are people in the world who still fail to comprehend the scope and scale of the poverty around them, who have become so swaddled and spoiled that they may as well be sleepwalkers.

You know what else I remember? I remember how the pandemic turned my neighbourhood into richer people’s racetracks, how they would roar down my street at night. They rode oversized rollerskates costing a quarter of a million dollars along tight roads full of parked cars and blasted through the stop signs at every intersection. They growled in the night, grumbling down my road at three, four, five in the morning, probably achieving top speeds of thirty miles an hour but making a lot of noise as they did so. Their owners thought a good use of their money was to buy fast cars and drive them somewhere they’d be slower than a galloping horse. Most of these were not even good-looking cars. Most of these looked like shit.

When I first wrote that paragraph, a quarter of a million dollars had not quite achieved the significance that it currently has. But more on that in a moment.

I didn’t grow up poor. I grew up well taken care of and fairly safe. But I did grow up more modestly, poorer, than many of the people I came to know, the kind of people you might meet at a university, or in a New England art gallery, or a convention overseas, or who might make analogies about Dante. I also grew up knowing other kids with families who had much less, families couldn’t always surface their floors or fix their windows or fill their fridges. Wedged between two classes, I grew up knowing people who had multiple bathrooms and multiple garages, as well as those who tried to hide the rot on the walls or who didn’t know how to clean up when their disaffected, distressed dog had shit in the semi-carpeted living room once again.

I never forget that dog, though I never told anyone that before.

You know what else I remember sometimes, at random, when my brain decides to reminisce? I remember taking a bus home from work after a terrible Hampshire day, feeling awful about my life, when an old schoolfriend’s younger sister greeted me with excitement and enthusiasm. She came from the same household as the shit-stained floor. She sat on the back seat of this bouncing bus and delightedly told me how, by the age of seventeen, she was finally going to become a mother.

And then I remember how we were encouraged, pushed, expected to move beyond and away from something such as that. Don’t be like those people. Create distance. Escape.

I stopped writing this thing for a while, because each time that I opened it I became sad or I became overwhelmed, and I wondered both what right I had to write about things like this, being the guy with a pension and a safe apartment, and also who would care to read it. There are likely many reasons that people don’t want to read about some of these experiences and situations and one is that they aren’t very much fun. Why read about people with shit-stained floors when you can do anything else, such as watch a television show about starship battles or elves going on an adventure. These shows have CGI now and it’s all very exciting. It’s hard to compete in a world of CGI shows, funny dog videos and services that deliver dinner to your door.

But then it happened again.

I am trying a different fancy café (we have so many now). I just got forced back a place in line, mere seconds from being served. Another patron, presumptive and impatient, slid between me and the coffee I ordered, snatching it away in a move that I would describe as all too practised, as smooth. Again, they had ordered the same drink as me, and it either never crossed their mind to see if another person might claim this order, or I was somewhere between invisible and insignificant compared to how well-dressed, well-presented they were.

Is that just in my head?

I stepped out onto the street, past a row of sports cars and luxury vehicles. They are all over the place now, and I rarely walk a minute before seeing something that costs more than my neighbourhood’s median annual income. And then there was that whiplash, that high-g experience as I was also reminded of this half-written draft and everything else it contained.

And then I was angry.

I stopped writing this because, in part, I don’t know what it says about me that I didn’t so much leave so many of my low income experiences behind as find ways to run from them. Growing up, I was subconsciously sold a story of aspiration that was all about making yourself better than people who were struggling like this, about doing everything you can to create distance between yourself and them, about finding ways to identify with and relate to a different class. Become richer, sure, but become separate too. I think there is something in some poorer, lower-income, working class mindsets where such people are encouraged to resent themselves, to feel embarrassed, to aspire to be or to pretend to be something else, and to lose that past as soon as you can. I went and re-watched old material by the stand-up comedian Billy Connolly wherein he talked about things like his family throwing coats on the bed to keep warm, then pretending that a kids’ argument over those coats was a fight over the eiderdown (“The coats are in the cloakroom, near the mezzanine.”). I watched another where he tells a story of a person falling from a plane’s undercarriage and of a worried local calling the authorities and asking them to come and remove the body not out of concern for the tragedy or the person’s welfare, but because “I think he’s working class.” I have also never forgotten Connolly venting his frustration at someone who said to him “I was going to buy a copy of the Big Issue [a magazine that supports the homeless and unhoused], but the man was smoking.”

Connolly’s take on this was “HE DOESNAE HAVE A FUCKIN’ HOOSE. ALLOW HIM A WEE FAG WHILE HE WORKS OUT WHERE HE’S GONNA SLEEP TONIGHT.”

That’s an anger I understand, but it’s also an anger I am baffled to not see more often, perhaps even all the time, expressed as it should be in proportion to the amount of poverty and hardship I see every day. When I first moved to Vancouver, I encountered dozens of people sleeping on the streets. When I returned as a Permanent Resident in 2019 there were hundreds. There must now be thousands occupying doorways or amongst the growing tent cities that are constantly moved from place to place, an ever-growing population that is pushed away whenever they get too close to those expensive apartments or luxury cars.

When I see these people, I think how only a handful of circumstances or coincidences separate me from being in that position. Bubble bubble, go those rising waters, those rising rents and prices, and I have only climbed a little higher.

A few years ago, I sat next to a person on a train who volunteered their dismay: “It’s such a shame these people don’t want to work,” they said, as if people willingly chose to live in freezing tents without running water or safety or income. And there is valid anger to be thrown at a person like that, but also perhaps the consideration that they have never been exposed to the mathematics or practicalities of poverty, never had to worry quite enough about the cost of living, and have only ever talked about poverty as if it was some curious other country. A remote place of foreigners.

But I still don’t get how anyone can talk of the shock of poverty when it is so ever-present. I don’t understand. Do they look away? Are these the same kinds of people who, surveys have increasingly shown, see their above-average incomes as being unremarkably normal? After all, it now seems that wealth (and poverty) substantially alter psychology.

Nine years ago, in the spring, I shared an essay similar to this one called On Poverty. I talked about the rising cost of food and housing in England, as well as my frustrations around how something that for me was ever-present precariousness seemed somehow surprising, shocking, to many other people. It took me nearly a year to articulate and I only published it because I ran out of patience. To my surprise, it was shared in all kinds of places. Writers I admired got in touch, activists reached out, someone from the UK housing charity Shelter contacted me.

It was already six years after “We Asked 100 People how they’re Coping with the Credit Crunch” and nothing had changed. There was a growing trend toward not buying property in London, but investing in property, to the point that properties that didn’t yet exist were already being pre-bought with the understanding that they would become more valuable and could then be sold to others. Homes were no longer most useful as somewhere to live, but as investments that would appreciate. While I can’t say that this first started in London, I have certainly seen this practice and its consequences everywhere from Vancouver to New England to cities across Europe and Australia and… perhaps you can tell me somewhere where this hasn’t yet begun to happen.

And it is now fifteen years after “We Asked 100 People how they’re Coping with the Credit Crunch” and nine years after On Poverty and all the things that haven’t stopped have only gained momentum. Bubble bubble, the waters keep rising, because whyever would they not? We are, at least, talking more about the trends that we see as the waters reach more of our ankles. In Canada now we talk about how real estate prices that have increased up to three hundred and thirty seven percent mean that Toronto’s housing price to income ratio is now six, while Vancouver’s is ten, how twenty percent of properties are owned by investors (including half of all new condominiums in Vancouver), how the nation’s households now owe more money than the entire GDP, how insolvent an entire generation is. We now do our own versions of stories about, say, how a furnitureless room just big enough for a bed is now nine hundred dollars a month (this kind of story is so familiar… it’s happening again…). In Britain, the food bank usage I was furious about a decade ago is increasingly acknowledged, with a dialogue around how having more food banks thank McDonald’s restaurants might not be a good thing, how an ongoing cost of living crisis pushes more people toward sex work, how raising a healthy family and maintaining a basic standard of living has become increasingly difficult or downright impossible, how ill health is on the rise while life expectancy has stopped increasing and young adult mortality has risen, how almost four and one quarter million of Britain’s children now live in poverty while their parents struggle to feed them (and themselves), all against a background of increasing stagnation. In the United States there is also greater awareness of how wages have stagnated while the cost of living has increased and of how property prices have again wildly outpaced earnings, and continue to do so in no small part because more new properties are bought for the exclusive purpose of being profit-making stock, not to mention how more and more people are not taking lower paying jobs simply because they know those jobs won’t allow them to cover even their most basic needs (there is also an examination of the attempts to fill these voids by relaxing child labour laws in some states and how it might not be a good thing for ten-year-olds to be working the McDonald’s night shift). I see cost of living and inflation discussion across Europe. In South America. Even at the bottom of the world.

But it should never have got this bad, should never have spread this far, and it has done so in part because we ignored the poorer people around us who were the canaries in the coal mine, whose experiences (separated from ours only by chance and coincidence) could very well have been our own, but were instead treated as something happening at a peculiar distance. Those first people caught up in the rising tides were not like us, not our concern. It is only now, as these stories increase and as these graphs grow and as these numbers multiply, that more of us are beginning to understand that the surging waters might well engulf us all. We cannot outpace economics much as we cannot outjump gravity.

And so maybe, just maybe, a few more of you are angry too. You should be.

Two of the challenges I had over the many months that I tried to write this work were trying to start it and trying to finish it. These may sound very fundamental, perhaps even existential, and I suppose they are. Longform writing has been difficult for me the last few years. Trying to find a fresh way to articulate my anger and frustration over something that I have already written about, in one form or another, so many times was hard. There are only so many times I can say that it’s happening again before I wonder if people care. If people care about the increasingly obvious truth that, for a growing number of us, it has essentially become too expensive to be alive, and that if you can’t afford to live, the only thing you can do, either slowly or quickly, is die. And often I wonder why people are not mad about this every day, all of the time, and why much of this increasing poverty and inequality and struggle to survive is still reported and remarked upon with that peculiar distance, rather than being one of the chief concerns of our time. It certainly is a chief concern if it is your day to day life.

And then the submarine happened.

By now just about everyone knows at least something about how the OceanGate Titan submersible was lost at sea, suffering a catastrophic failure as a result of what seems to have been reckless policies and a contempt for safety standards. Tickets for a spot on this tiny, dangerous submarine cost a quarter of a million US dollars, while two nations and multiple air and sea forces invested tremendous resources in trying to locate the missing vessel. I have since witnessed what I think can generously be described as a lack of sympathy for this mixture of carelessness and privilege, as well as the enormous response that had to be deployed in an attempt to rescue rich tourists considered to have made poor choices. In particular, many people noted the contrast between the widespread coverage and intense efforts on behalf of five missing rich people versus the relative dismissal of the recent death of hundreds of refugees, including around a hundred children, in a Mediterranean shipwreck. It was an extremely transparent case of starkly different treatment based upon status.

And I had already woven my submarine analogies throughout half of these paragraphs.

This response is as important as the events themselves. It reflects a growing discontent around the wealth divide and a contempt for the rich, particularly the powerful rich, those who can make decisions that have enormous consequences that they themselves will not have to face. The past week I’ve been presented with thousands of tweets and short video essays by people explaining why they feel so little sympathy and how they’ve had enough. These are presented alongside more and more stories covering things such as the Clearlink CEO celebrating a worker selling their family dog in order to keep their job, or the increasing belief that ongoing inflation is in part caused by a transparent and unregulated desire for profit (including perhaps thousand dollar flip-flops sold by minimum wage staff). In the last few years it’s been revealed that even economic reporting itself is biased toward talking about richer, more comfortable people.

It’s almost July as I prepare to publish this work. The bagels that were, it turns out for only a brief moment, price frozen at three dollars are now thirty cents more expensive, a further ten percent price rise. I look at them and I remember what it was like to count every penny I spent when I was food shopping and I decide that I will include the following paragraph, which I was going to cut from this draft:

You know what the fresh pastries in the supermarket look like when you have only a handful of coins in your pocket? Those cherry-red centres, that glistening applesauce oozing out between crisp layers of puff pastry? They look like lights hung for a festival, they look as bright as Christmas decorations. They lose some of their sense of reality.

I’m not going to celebrate rich tourists lost at sea, but I’m glad it has lead to more people expressing their frustration, their discontent, their helplessness against economic forces that strike them, strand them, like a tidal wave, the surging waters that they cannot begin to climb clear of. I don’t think this means things will change this month, or this year, and I believe that change against forces and trends that have already developed so much momentum will require much more energy, much more pushback. I hope they continue to be angry, that they become angrier still, that they keep articulating and focusing their rage about the growing inequality and unaffordability around them as it begins to affect more and more people. That they express how disgusting it is that it is happening again.

Nine years ago I wrote that I felt we were regressing to the Victorian era, but now I wonder if we’re falling back even further than that. In my world of CGI shows, funny dog videos and services that deliver dinner to my door, almost all of the people who deliver that dinner or who will make me a coffee or who will drive me to the airport, or who perform all those tasks I can request when I throw money at stuff like a wizard casting a spell, are paid garbage and treated like they are disposable. This is usually because they are, and they have few other options. They are not lazy or stupid and we are only separated from one another by circumstances or coincidence, things we had about as much control over as weather, as rising tides, as economic forces with all the power of a tidal wave and which could still strike again and sink yet more of us. It could be happening again. Bubble bubble.

A significant factor in the success of someone like me, of the safer position I now find myself in, is luck, and we don’t talk about that enough.

People are trying so hard to survive. Last week someone broke through the latticework on the door of our building’s dumpster enclosure so that they could slide a hand through a tiny, sharp filigree of twisted metal and operate the handle. They did this in order to reach the trash inside, because their life had become so difficult that they needed to risk harming themselves in order to get trash.

Two blocks away, I finished writing in my local fancy café and stood briefly to return my cup to the counter, which is a common habit in the Pacific Northwest and takes but a moment. The patron next to me looked up from behind gold-rimmed, heart-shaped sunglasses.

“Oh, you don’t have to do that here,” she said. “They have people who will do that for you.”

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Everett Williams for Nordstrom

https://www.instagram.com/everettwilliams/

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Devalued.

#mannequin#sale#nordstrom#department store#vancouver#local#photographers on tumblr#original photographers

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nordstrom has announced it is closing all of its Canadian stores, a number of which are located in Toronto, cutting 2,500 jobs in the process.

The fashion retailer made the announcement on Thursday, noting that it does not “see a realistic path to profitability for the Canadian business.”

The move will result in the eventual closure of all of the company’s Nordstrom and Nordstrom Rack locations across Canada, including a flagship store located at Toronto’s Eaton Centre.

The company also operates stores at Yorkdale Shopping Centre, Vaughan Mills Shopping Centre and CF Sherway Gardens. [...]

Continue Reading.

Tagging: @politicsofcanada

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

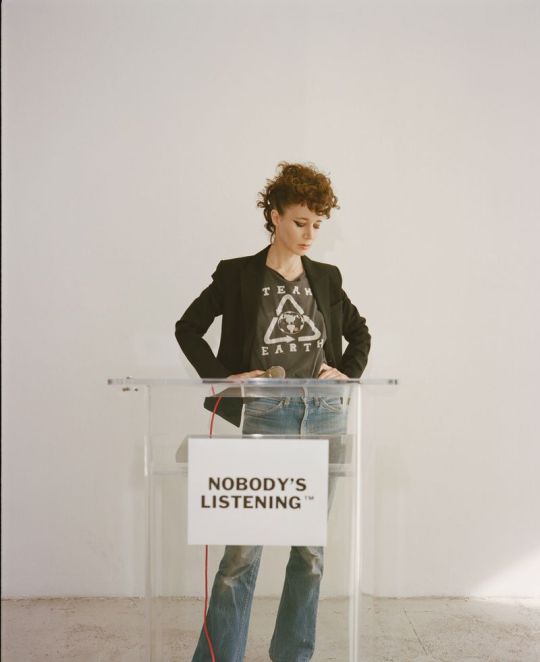

Miranda July by Olivier Zahm styled in vintage and clothes from Nordstrom by Masha Orlov for Purple Magazine

10 notes

·

View notes