#Norman Engel

Text

“Texas Spring”, 2019 by Norman Engel

#Norman Engel#Texas artist#southwest art#Texas art#Texas hillcountry#nature#en plein air#Texas#landscape painting#landscape#bluebonnets#texas hill country#acrylic on canvas

123 notes

·

View notes

Text

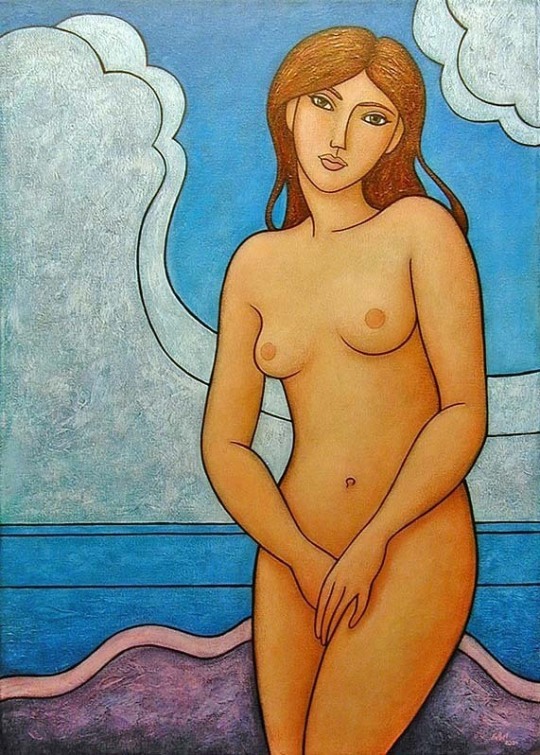

“Venus”, 2004 by Norman Engel

231 notes

·

View notes

Text

🎨 Norman Engel

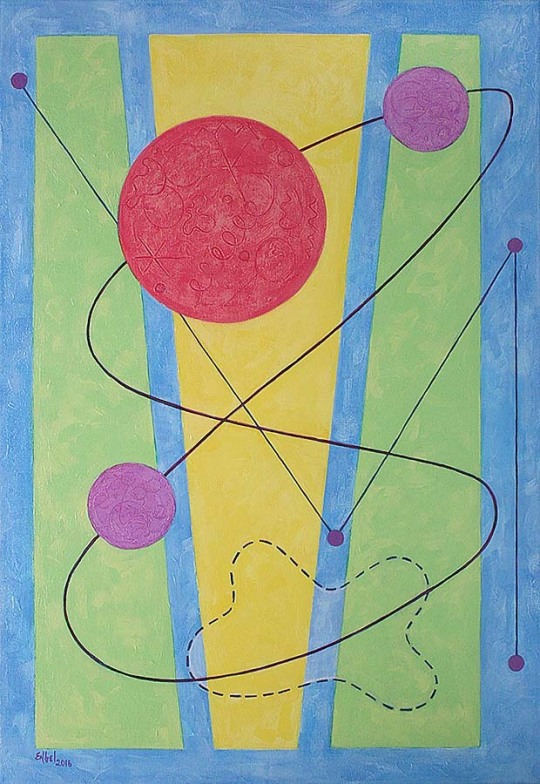

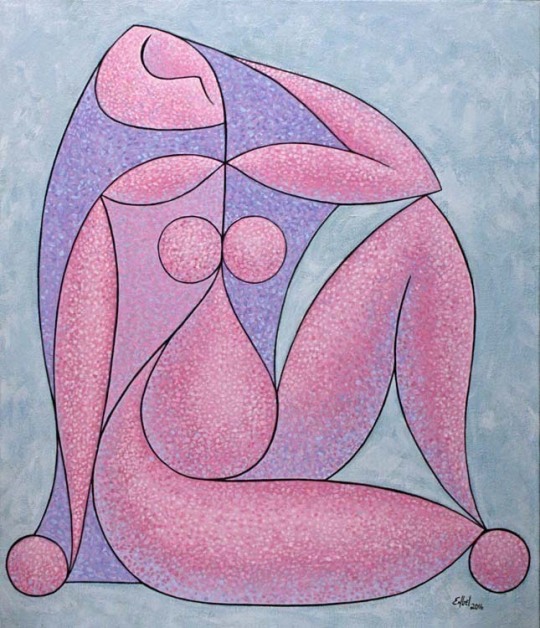

Norman Engel - “Interior Universe” - 2016

Norman Engel - “Babapoosha” - 2007

Norman Engel - “Tropical Punch” - 2007

Norman Engel - “Seated Woman” - 2016

Norman Engel - “Abstract Woman” - 2016

Norman Engel - “Line Dance” - 2013

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Prickly Pear Blossoms”, 2011 by Norman Engel

Source: engelart

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

i disagree with you and cordelia that engels just got unlucky in the division of labor. marx was quite obviously smarter than him imo

i'm assuming you're the same person who sent me a similar message a week or so ago. but anyway i don't really remember saying this tbh so maybe you'd have to point me to where that was/the context. regardless i guess i would disagree (apparently with myself) to some extent in that i think marx was definitely the sharper thinker in many ways, but i also think it partly had to do with their backgrounds. engels was an autodidact while marx had years of specialized university training. as a degreeless autodidact, this isn't intended as a dig at autodidacticism or high praise to universities and their students, but it does get at some of the difficulties i think engels had to work through as a thinker which marx had less issue with. norman levine's work on marx and engels highlights some of this in ways that i think are pretty pursuasive, although i think he bends the stick too far -- basically treating engels as an undereducated idiot.

my usual take is that i prefer the young engels and the late marx, which i think has something to do with their "division of labor", as engels really initiates the critique of political economy and a lot of the things i go to the late marx for, but im not sure engels would've been able to really go as far as marx did in pushing that critique to its eventual (albeit unfinished) resting place. over time, i think engels' thinking sorta stagnates after meeting marx and never quite returns to the level he'd achieved in his youth, largely because he's no longer in the same intellectual circles and is having to dedicate so much of his time to things that don't involve spending months in the library. i guess part of that could be chalked up to a kind of "luck" (and more accurate than assuming engels was a dumbass by nature), but it's not reducible to their division of labor alone as if they were the only factor in each other's lives.

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

In line with our historic gender-conditioning, women have aimed to please and have sought to avoid disapproval. This is poor preparation for making the leap into the unknown required of those who fashion new systems. Moreover, each emergent woman has been schooled in patriarchal thought. We each hold at least one great man in our heads. The lack of knowledge of the female past has deprived us of female heroines, a fact which is only recently being corrected through the development of Women’s History. So, for a long time, thinking women have refurbished the idea systems created by men, engaging in a dialogue with the great male minds in their heads. Elizabeth Cady Stanton took on the Bible, the Church fathers, the founders of the American republic. Kate Millet argued with Freud, Norman Mailer, and the liberal literary establishment; Simone de Beauvoir with Sartre, Marx, and Camus; all Marxist-Feminists are in a dialogue with Marx and Engels and some also with Freud. In this dialogue woman intends merely to accept whatever she finds useful to her in the great man’s system. But in these systems woman—as a concept, a collective entity, an individual—is marginal or subsumed.

In accepting such dialogue, thinking woman stays far longer than is useful within the boundaries or the question-setting defined by the “great men.” And just as long as she does, the source of new insight is closed to her.

Revolutionary thought has always been based on upgrading the experience of the oppressed. The peasant had to learn to trust in the significance of his life experience before he could dare to challenge the feudal lords. The industrial worker had to become “class-conscious,” the Black “race-conscious” before liberating thought could develop into revolutionary theory. The oppressed have acted and learned simultaneously—the process of becoming the newly conscious person or group is in itself liberating. So with women.

The shift in consciousness we must make occurs in two steps: we must, at least for a time, be woman-centered. We must, as far as possible, leave patriarchal thought behind.

To be woman-centered means: asking if women were central to this argument, how would it be defined? It means ignoring all evidence of women’s marginality, because, even where women appear to be marginal, this is the result of patriarchal intervention; frequently also it is merely an appearance. The basic assumption should be that it is inconceivable for anything ever to have taken place in the world in which women were not involved, except if they were prevented from participation through coercion and repression.

When using methods and concepts from traditional systems of thought, it means using them from the vantage point of the centrality of women. Women cannot be put into the empty spaces of patriarchal thought and systems—in moving to the center, they transform the system.

— Gerda Lerner, The Creation of Patriarchy

#just highlighted some fav parts#also it's a long one it's all good...#gerda lerner#feminism#quote#what I'm reading#moth.txt

164 notes

·

View notes

Text

Critical Theory Recommended Reading List:

Principles of Communism (Friedrich Engels)

Wage-Labour and Capital Value, Price and Profit (Karl Marx)

Das Kapital (Karl Marx)

The Communist Manifesto (Karl Marx)

On Practice & On Contradiction (Mao Zedong)

The Motorcycle Diaries (Che Guevara)

Latin America Diaries (Che Guevara)

Reminiscences of the Cuban Revolutionary War (Che Guevara)

Guerilla Warfare (Che Guevara)

Che (Jon Lee Anderson)

Socialism: Utopian and Scientific (Friedrich Engels)

The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State (Friedrich Engels)

Orientalism (Edward W. Said)

The Unwomanly Face of War (Svetlana Alexievich)

The Wretched of The Earth (Frantz Fanon)

A Dying Colonialism (Frantz Fanon)

Black Skin White Masks (Frantz Fanon)

Inglorious Empire (Shashi Tharoor)

Remembering Che (Aleida March)

Against Empire (Michael Parenti)

Blackshirts & Reds (Michael Parenti)

Revolutionary Suicide (Huey P. Newton)

Confessions of an Economic Hitman (John Perkins)

The Mismeasure of Man (Stephen Jay Gould)

The State and the Revolution (V.I. Lenin)

Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism (V.I. Lenin)

Imperialism in The 21st Century (V.I. Lenin)

Liberalism A Counter History (Domenico Losurdo)

23 Things They Don't Tell You About Capitalism (Ha-Joon Chang)

October (China Miéville)

Kill Anything That Moves (Nick Turse)

Blitzed: Drugs in Nazi Germany (Norman Ohler)

Late Victorian Holocausts (Mike Davis)

Ten Myths About Israel (Ilan Pappe)

How Europe Underdeveloped Africa (Walter Rooney)

Reform or Revolution (Rosa Luxemburg)

Settlers: The Mythology of the White Proletariat (J. Sakai)

Killing Hope (William Blum)

Unequal Exchange and the Prospects of Socialism (Arghiri Emmanuel)

Unequal Exchange: A Study of Imperialism and Trade (Arghiri Emmanuel)

The Wealth of Some Nations (Zak Cope)

Divided World Divided Class (Zak Cope)

The Law of Worldwide Value (Samir Amin)

Unequal Development (Samir Amin)

An Economic History of the U.S.S.R (Alec Nove)

Human Rights in the Soviet Union (Albert Szymanski)

Is the Red Flag Flying? (Albert Szymanski)

Soviet Democracy (Pat Sloan)

The Industrialisation of Soviet Russia: The Socialist Offensive (R.W. Davies)

Soviet Communism: A New Civilisation (Sidney and Beatrice Webb)

Socialism in the Soviet Union (Jonathan Aurthur)

The Soviet Form of Popular Government (The U.S.S.R Academy of Sciences)

Workers Participation in the Soviet Union (Mick Costello)

The Great Conspiracy (Michael Sayers and Albert E. Kahn)

The Soviets and Ourselves: Two Commonwealths (K.E. Holme)

The Old Social Classes and the Revolutionary Movements of Iraq (Hanna Baratu)

South Yemen A Marxist Republic in Arabia (Robert W. Stookey)

The Arab Left (Tareq Y. Ismael)

Post-Marxism and The Middle East (Feleh A. Jabar)

The Unmaking of Arab Socialism (Ali Kodri)

The Hundred Years' War on Palestine (Rashid Khalidi)

The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine (Ilan Pape)

A Strategy for the Liberation of Palestine (The Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine)

Roadside Picnic (Arkady and Boris Strugatsky)

Blood in My Eye (George Jackson)

Why You Should Be a Trade Unionist (Len McCluskey)

The Pitfalls of Liberalism (Kwame Ture)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marx’s conception of the phases of communism should not be confused with ‘the dictatorship of the proletariat’, which he defines as a political transitional stage between capitalism and communism. As he clearly states in the Critique: ‘Between capitalist and communist society lies the period … in which the state can be nothing but the revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat’. The latter represents the democratic control of society by the ‘immense majority’, the producers, who use political power as a lever to eliminate class domination by revolutionizing the social relations of production. Engels spells out the thoroughly democratic character of this political transition stage in his critique of the 1891 Erfurt Program: ‘If one thing is certain it is that our party and the working class can only come to power under the form of a democratic republic. This is the specific form of the dictatorship of the proletariat’. Marx and Engels use the term ‘dictatorship’ as it was understood in Roman law – as a magistrate elected by the Roman Senate for a limited period of time to deal with an emergency and whose rule is disbanded upon its termination. As Norman Levine has argued, it has nothing to do with later Leninist conceptions of a prolonged ‘transitional phase’ led by a political party that monopolizes power. The political transition period discussed by Marx is not a distinct form of society, since it comes between capitalist and socialist or communist society. It is instead a political stage in which the old mode of production is undermined and negated through an ongoing revolutionary process. Once this process is completed the dictatorship of the proletariat becomes superfluous, since with the abolition of class society and value production the proletariat is abolished alongside all other classes. What then emerges is the first or initial phase of communism, in which a completely new form of production relations prevails.

Peter Hudis, Imagining Society Beyond Capital

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

“prickly pear” 2021 by Norman Engel

#Norman Engel#Texas artist#southwest art#Texas art#Texas hillcountry#nature#en plein air#Texas#landscape painting#landscape#prickly pear#cactus flowers#sold#private collection

35 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“kitty kitty meow meow”, 2020 , by Norman Engel

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

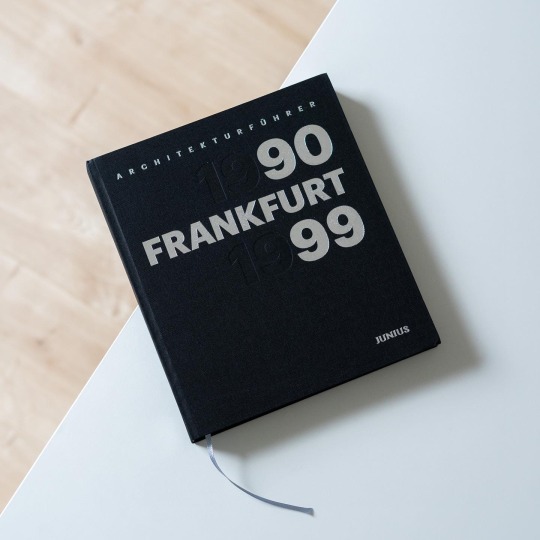

The 1990s in Frankfurt/Main started with a bang: Murphy/Jahn’s Messeturm was completed in October 1990 and at 256 meters outdid the city’s former highest building by some 100 meters. But at the same time it also paved the way for a new generation of high-rises, one that was no longer strictly bound to the postwar example of the curtain wall and instead introduced emblematic, sculptural forms. The building heralded a decade of increased high-rise construction, a result of Frankfurt’s building department’s plannings walking hand in hand with the city’s ascent to a European economic powerhouse. That the 1990s were an exciting decade both in terms of architecture and culture proves the already fifth volume of Wilhelm Opatz’ series, just released by Junius Verlag: „Architekturführer Frankfurt 1990-1999“ in the proven juxtaposition of architecture, history and culture provides a comprehensive portrait of the decade that is much more than „just“ an architectural guide. Ten exemplary buildings including the previously mentioned Messeturm, Gustav Peichl’s extension of the Städelmuseum and Norman Foster’s Commerzbank Tower exemplify the city’s grown self-confidence. The latter was furthered by the head of the building department who envisioned high quality buildings designed by renowned international architects, an intent that very much materialized: Kohn Pedersen Fox, Frank Gehry, Toyo Ito and Hans Kollhoff all completed buildings during the 90s in FFM. But as Opatz’ selection proves German protagonists were well able to keep up with their international peers as e.g. Max Bächer’s timeless Parkfriedhof Heiligenstock buildings or Michael Landes’ congenial side-by-side of old and new at the Union Areal demonstrate.

In between the architecture the reader learns about Rosemarie Trockel’s 1994 „Frankfurter Engel“ from no other than Kasper König or that Arvo Pärt in 1995 recorded „Alina“ at Festeburgkirche for ECM.

These interspersed excursions together with the carefully selected architecture take the reader on a stroll through a decade that saw the city come into its own. A warmly recommended „non-architects‘ architectural guide“.

#architectural guide#junius verlag#architecture#germany#architektur#frankfurt/main#1990s#book#architecture book

26 notes

·

View notes

Note

no offense but i don't think you're justified in dismissing "worldview marxism" as flippantly as you do if you haven't read at least some decent amount of hegel. i'm sure heinrich has and so it's okay if you want to defer to him but you should stop the condescending tone toward people who have done their homework and agree with worldview marxism

i just scrolled through like 4 months of posts trying to figure out when the last time i even mentioned worldview marxism was and couldn't rly find anything so not sure what this is even really a response to (or where i would've been condescending!) but there are a couple of things id say here i guess

first of all, i'm not really all that dismissive of worldview marxism (and frankly, neither is heinrich). sure, the term has some critical intent behind it, but it's mostly just a description of the dominant form that marx-reception took after marxs death. the point of highlighting worldview marxism isn't to locate it as a moment in history where everyone was an idiot until people like me came along and started getting everything right, it's to talk about a real tendency to generalize elements of marxs work into a set of principles or general laws which govern all of human history and even the natural world outside of it. i think this runs up against marxs own explicit statements in the best of his work, although much of that is in manuscripts which went unpublished until after the heyday of worldview marxism (and i don't think this is merely a coincidence either).

as for the hegel angle: sure i haven't read much hegel, but that would only be a meaningful shortcoming if such a worldview were the result of a marxism which was steeped in hegel. i don't really think this is true. it largely comes out of second-hand popularizers who (at best) were regurgitating engels' later work as being the foundations for what marxism was all about. but engels himself was ultimately not steeped in hegel, as people like norman levine (and, to a different extent, terrell carver) have shown. even lukacs, arguably the greatest and most sophisticated worldview marxist, highlights engels' own shortcomings with dialectical thought (in fact, he was the first notable person to do this). this is also not to simply load all of the problems onto engels and dismiss him instead (and similarly, despite what everyone thinks, heinrich is also not dismissive of engels). it is only to highlight his limits and describe the very real history of marx-reception through engels' popular works, many of which we can undoubtedly say -- and without any reference to hegel whatsoever -- reveal issues in engels' interpretation of marx's critique of political economy (which we know from their correspondence he actually knew very little about beyond reading volume 1 when it was published).

if anything, the marxists which could claim some affinity to hegel and who could (and did) make the strongest case for the relationship between hegel and marx were often the people like the early initiators of the german new reading: backhaus, reichelt, and schmidt (who, from what i can tell, coined the term 'worldview marxism' and wrote about marx's various appropriations of hegel). others like jairus banaji and cyril smith have shown the limits of dominant interpretations of marxs capital through bad readings of hegel (especially in the case of lenin) where "the dialectical method" is turned into a contentless architecture which can simply have all of its parts relabeled and converted into a marxian system. this ignores the intimate relationship between essence and appearance in hegel, and in fact completely divorces them.

heinrich's "innovation", if it can even be called that, is that he distances himself from both of these camps because each offers an interpretation of marx via hegel (lenin & lukacs; the early german new reading/systematic dialectics/etc) which only approaches hegel *through* marx as a guide to making sense of his work, rather than each as relatively independent thinkers in their own right (although arguably people like schmidt were a bit more sensitive to this than lukacs and marcuse who treat hegel as a proto-marx).

now you can say that i'm merely deferring to an authority on all of this because i haven't read enough hegel (and to some extent that's definitely true!) but if anything i think that this is basically beside the point since the issues of worldview marxism are largely independent of hegel in their actual context and have a much more straightforward history in the reception and interpretation of marxs texts for other reasons. to the extent that hegel is even involved, i think that the scholarship is pretty overwhelmingly on my side about this. now i guess you could say the scholarship & my own understanding of hegel (from people like heinrich, banaji, smith, etc) is wrong, and maybe you'd even be right, but frankly this only discloses another wrinkle in all of this (which heinrich and postone are both good for), namely that the hegel-marx connection is completely independent of our understanding of hegel. we could completely and totally understand hegel, better than himself even, but that has absolutely nothing to do with marx's reading of him, which might deviate significantly (and, by many accounts, probably does).

marx was necessarily a productive misreader of hegel in many ways -- and how could he not be, since like early 20th century marxists, he didn't have access to many of the manuscripts that help illuminate the thought of the person he's studying, like the jena lectures for example. more importantly, even if marx did read hegel as a worldview marxist would, this doesn't even mean we have to agree with it. this is a big reason why heinrich is very clear that reading and understanding hegel in the 21st century is not some magic key to making sense of marx. there might be some utility in reading hegel, and certainly it will clarify moments of marx's biography, but there are other (more preferable) ways of accounting for the contours of marxs own intellectual development as well as the history of marxisms without simply having to stop and read hegel, which is not the same as doing your homework.

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

Masc or neutral names that I could use Mel as a nickname for?? maybe dark academia or void/space themed but that's not required !

Amel

Meaning: hope, aspiration

Origin: Arabic

Armel

Meaning: bear prince

Origin: Old Welsh

Carmelo

Meaning: garden

Origin: Hebrew

Melanthios

Meaning: black flower

Origin: Greek

Melchior

Meaning: king of the light

Origin: Hebrew

Related names: Melker

Melech

Meaning: king

Origin: Hebrew

Melisizwe

Meaning: leader of the nation

Origin: Xhosa

Meliton

Meaning: honey

Origin: Greek

Mellan

Meaning: little delightful one

Origin: Old Irish

Melle

Meaning: meeting

Origin: Germanic

Melor

Meaning: acronym for Marx, Engels, Lenin, October Revolution

Origin: Russian

Melqart

Meaning: king of the city

Origin: Phoenician

Melvin

Meaning: bad town

Origin: Norman French

#writeblr#names#character names#oc names#oc ideas#name ideas#name suggestions#new names#writers on tumblr#mystery guest

12 notes

·

View notes