#Paul Celan: Poet Survivor Jew

Text

The word Geschwätz is a common German term for everyday chitchat. But Felstiner suggests it may have for Celan “hints of Babel and the loss of original language.” He explains:

For in Walter Benjamin’s essay “On Language in General and on the Language of Man,” Geschwätz designates empty speech after the Fall, speech without Adam’s power of naming... The babbling of Celan’s Jews is a comedown—via the cataclysm that ruined Benjamin—from God-given speech.

— Anne Carson, Economy of the Unlost: (Reading Simonides of Keos with Paul Celan)

#m#John Felstiner#Walter Benjamin#On Language in General and on the Language of Man#Paul Celan: Poet Survivor Jew#Gespräch im Gebirg#Paul Celan#Anne Carson#Economy of the Unlost#Economy of the Unlost: (Reading Simonides of Keos with Paul Celan)#Simonides of Keos#nonfiction#Babel#language#lost language

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gods as nearby as the vulture’s nail.

—Paul Celan, 1943 from Paul Celan: Poet, Survivor, Jew (1995) by John Felstiner

1 note

·

View note

Text

we love one another like poppy and memory,

we slumber like wine in the seashells,

like the sea in the moon’s blood-beam

–

It is time.

-Paul Celan, "Corona" (trans. Susan Gillespie)

Time turns back on its shell.

In the mirror is Sunday.

It is time.

“Corona,” from Paul Celan, Romanian Austro-Hungarian German Jew (all identities not quite defined as such in his youth). Celan was the sole survivor from his family; his parents died in Nazi labor camps.

Celan became the great poet of the postwar, but the language of his executioners was lifelong source of both torment and creativity.

Writing in German was to redeem it, while “passing through the thousand darknesses of deathbringing speech”

[Anselm Kiefer, after Celan, 2006]

I love this poem for all the reasons but also because Celan echoes Rilke’s famous opening cry, “Herr: es ist Zeit” (“Lord, it is time”) and responds definitively, “Es ist Zeit.”

It is time.

Rainer Maria Rilke, Herbsttag, trans. William Gass, “Autumn Day”

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

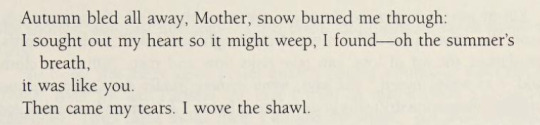

Paul Celan, "Black Flakes" from Early Poems (1940-1943) (translated by John Felstiner)

Text ID: Autumn bled all away, Mother, snow burned me through: / I sought out my heart so it might weep, I found — oh the summer's breath, / it was like you. / Then came my tears. I wove the shawl.

Translator's commentary on translating the closing line, from Paul Celan: Poet, Survivor, Jew (1995: 21): "To close, this elegy again poses growth against wounding: Kam mir die Träne. Webt ich das Tüchlein. At first I tried to match those five-syllable cadences: "Tears came to me then. I knitted the shawl." But Webt ich means "I wove." The advent of tears balances the weaving of a shawl, the unmaking force of grief meets the poem's own making: "Then came my tears. I wove the shawl." Answering loss with language, this poem weaves a text against winter. "Schwarze Flocken" (Black Flakes) holds in a single moment the European Jewish catastrophe, Paul's personal loss, and a poet's calling. We hear his mother ask for a shawl: he writes a poem, restoring to her something, at least, in the mother tongue."

#paul celan#black flakes#paul celan: early poems#poetry#literature#lit#quotes#quotations#book quotes#literary quotes#quote#grief#loss#translation#translator#winter#poetry quotes#poetry excerpt#xo

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Poetry no longer imposes, it exposes itself.” --Paul Celan, quoted in John Felstiner, Paul Celan: Poet, Survivor, Jew

24 notes

·

View notes

Note

What are you reading rn?

Paul Celan: Poet Survivor Jew, by J Felstiner

2 books of interviews w Emmanuel Levinas; Ethics & Infinity, and Is it Righeous to Be?

The Need for Roots, Simone Weil

And just today I’m starting the novel Tranist by Anna Seghers

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Economy of the Unlost by Anne Carson

The ancient Greek lyric poet Simonides of Keos was the first poet in the Western tradition to take money for poetic composition. From this starting point, Anne Carson launches an exploration, poetic in its own right, of the idea of poetic economy. She offers a reading of certain of Simonides' texts and aligns these with writings of the modern Romanian poet Paul Celan, a Jew and survivor of the Holocaust, whose "economies" of language are notorious. Asking such questions as, What is lost when words are wasted? and Who profits when words are saved? Carson reveals the two poets' striking commonalities.

In Carson's view Simonides and Celan share a similar mentality or disposition toward the world, language and the work of the poet. Economy of the Unlost begins by showing how each of the two poets stands in a state of alienation between two worlds. In Simonides' case, the gift economy of fifth-century b.c. Greece was giving way to one based on money and commodities, while Celan's life spanned pre- and post-Holocaust worlds, and he himself, writing in German, became estranged from his native language. Carson goes on to consider various aspects of the two poets' techniques for coming to grips with the invisible through the visible world. A focus on the genre of the epitaph grants insights into the kinds of exchange the poets envision between the living and the dead. Assessing the impact on Simonidean composition of the material fact of inscription on stone, Carson suggests that a need for brevity influenced the exactitude and clarity of Simonides' style, and proposes a comparison with Celan's interest in the "negative design" of printmaking: both poets, though in different ways, employ a kind of negative image making, cutting away all that is superfluous. This book's juxtaposition of the two poets illuminates their differences--Simonides' fundamental faith in the power of the word, Celan's ultimate despair--as well as their similarities; it provides fertile ground for the virtuosic interplay of Carson's scholarship and her poetic sensibility.

#ooc:// resources / all#ooc:// resources / texts#[ i don't know if i'll find any use of this but it's worth a shot ]#** anne carson

1 note

·

View note

Text

Paul Celan's Engführung

from Engführung/ Strait-steering

Paul Celan

Deported into the

Terrain

with the unmistakable Trace:

Grass, asunder-written. The Stones, white

with the Shadows of the Stalks:

Read no more – look!

Look no more – go!

Go, your Hour

has no Sisters, you are –

are at-home. A Wheel, slowly,

rolls out of itself, the Spokes

clamber,

clamber on blackish Field, the night

needs no Stars, nowhere

asks it after you.

*

Nowhere

asks it after you –

The Place, where they lay, it has

a Name – it has

none. They lay not there. Something

lays between them. They

saw not through.

Saw not, no,

spoke of

Words. None

awoke, the

Sleep

came over them.

This is an excerpt from Celan’s “Engführung” (composed 1958). The title poses the first of many translation problems: according to Duden, “Engführung” means, in musical terms, “(Musik) sich überschneidendes Einsetzen von aufeinander folgenden Stimmen (besonders in der Fuge)” [(Music) the overlapping insertion of consecutively following voices (especially in the fugue)] as well as “(bildungssprachlich) enge Verschränkung, Zusammenführung; enge Beziehung aufeinander,” that is, a kind of entanglement or interleaving, a bringing into tight relation. The English word for the musical term “Engführung” is typically “stretto” (from the Italian), and John Felstinter notes that “when a French translation was prepared, Celan approved Strette for Engführung” (Felstiner, Paul Celan, Poet, Survivor, Jew, 118). The benefit of “stretto” is that it also recalls the musical reference of Celan’s earlier poem “Todesfuge,” though in that poem “Engführung” has other connotations as well: “wir schaufeln ein Grab in den Lüften da liegt man nicht eng” (we shovel a grave in the air there lies one not cramped [eng]). In my translation, I chose “Strait-steering" for the title, though this is entirely preliminary, a first go. Throughout, I tried to abide by the mandate to take extreme literalism as my methodology. I thus attempted to preserve the compound of the German, and the sense of being led (or steered) into the narrow, the cramped – into the grave. But I’m still trying to think of ways to translate the multiple resonances of the word while maintaining a certain “literality.”

My translation of the first word – the participle verbracht – is also a problem: the verb can mean to “deport,” which I think is the sense that is being invoked here, but it can also mean – more “plainly” – to be transferred, taken, removed (in another usage, it can also have a temporal sense – Zeit verbringen meaning “to spend or pass the time”). Felstiner helpfully expounds on the translation of verbracht: “Celan once told someone that he had ‘spent’ (verbracht) the war years in labor camps. Does verbracht have a technical sense too? A French translation of his poem that Celan ‘guided’ begins with Déporté (‘Deported’), but German documents regularly used the word deportieren, and Celan translated déporter in Night and Fog by deportieren, verschleppen, aussiedeln (4:79, 81)” (119). Felstiner’s decision to translate the verb as “Taken off to…” is an excellent solution, but it also veers a bit from “literality.”

[…]

German:

VERBRACHT ins Gelände mit der untrüglichen Spur: Gras, auseinandergeschrieben. Die Steine, weiß, mit den Schatten der Halme: Lies nicht mehr – schau! Schau nicht mehr – geh! Geh, deine Stunde hat keine Schwestern, du bist – bist zuhause. Ein Rad, langsam, rollt aus sich selber, die Speichen klettern, klettern auf schwärzlichem Feld, die Nacht braucht keine Sterne, nirgends fragt es nach dir. * Nirgends fragt es nach dir – Der Ort, wo sie lagen, er hat einen Namen – er hat keinen. Sie lagen nicht dort. Etwas lag zwischen ihnen. Sie sahn nicht hindurch. Sahn nicht, nein, redeten von Worten. Keines erwachte, der Schlaf kam über sie.

(sorry, the formatting is messed up)

#mattjohnson #foundintranslationagain #celan

0 notes

Text

Delay, disappointment and hunger are experiences catalytic for poets. When Simonides went to dine with Hieron, he had to complain of hare and snow withheld. We saw these deprivations moved him to compose two poems that comment on the erosion of the ancient host/guest convention and parody the hollow diction in which relations between xenoi may come to be framed, once money replaces love in the structure of the event. When Celan went to visit Martin Buber, he experienced deep moral disappointment in the encounter and composed a poem about the “loss” and “salvaging” of certain words. Felstiner summarizes what went wrong with the encounter:

Buber came to Paris in September 1960. . . . Celan, just back from his comfortless visit with Nelly Sachs in Stockholm, telephoned and went to Buber’s hotel on 13 September. He took his copies of Buber’s books to be signed and actually kneeled for a blessing from the 82- year-old patriarch. But the homage miscarried. How had it felt (Celan wanted to know) after the catastrophe, to go on writing in German and publishing in Germany? Buber evidently demurred, saying it was natural to publish there and taking a pardoning stance toward Germany. Celan’s vital need, to hear some echo of his plight, Buber could not or would not grasp.

— Anne Carson, Economy of the Unlost: (Reading Simonides of Keos with Paul Celan)

#m#Paul Celan: Poet Survivor Jew#John Felstiner#Paul Celan#Pierre Joris#Breathturn into Timestead: The Collected Later Poetry#German#Martin Buber#Die Schleuse

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘Poems are “gifts to the attentive,”’

—John Felstiner quoting —Paul Celan, 1943 from Paul Celan: Poet, Survivor, Jew (1995)

0 notes