#President Joseph R. Biden Jr.

Text

President Joseph R. Biden, Jr. Approves Major Disaster Declaration for Florida

FEMA announced that federal disaster assistance has been made available to the state of Florida to supplement state, tribal and local recovery efforts in the areas affected by Hurricane Ian beginning Sept. 23 and continuing.

The President’s action makes federal funding available to affected individuals in Charlotte, Collier, DeSoto, Hardee, Hillsborough, Lee, Manatee, Pinellas and…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

OFFICIAL BALLOT FOR PRESIDENT

Joseph R. Biden Jr. (Democratic party)

Case Number 23SC188945 (Republican party)

408 notes

·

View notes

Text

President Joseph R. Biden, Jr. today announced the designation of a Presidential Delegation to Germany to attend the Opening Ceremony of the Invictus Games on Saturday, September 9, 2023.

#prince harry#duke of sussex#invictus games#the duke of sussex#harry and meghan#prince harry the duke of sussex#the duke and duchess of sussex#uk royal family#royal family uk#prince harry duke of sussex#the duchess of sussex#brf#british royal family#meghan the duchess of sussex#duke and duchess of sussex#the invictus games

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

"NOW, THEREFORE, I, JOSEPH R. BIDEN JR., President of the United States of America, by virtue of the authority vested in me by the Constitution and the laws of the United States, do hereby proclaim March 31, 2024, as Transgender Day of Visibility."

Google it. Those words. Copy & paste them into Google. You can find them six paragraphs down in his "Proclamation" on the Whitehouse website.

That's it then; Easter Sunday. The man couldn't even wait until Monday. It was too important to him to slap you in the face.

#god is a republican#make america great again#donald trump#Gun control#Freedom#kyle rittenhouse#suck my freedom#gop#republicans#conservatives#election#congress#independence

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

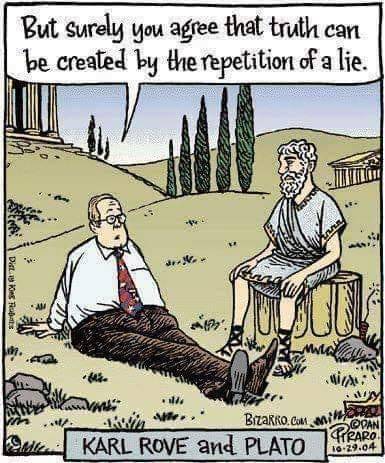

[Dan Piraro]

* * * *

A watershed moment for the truth.

February 16, 2024

ROBERT B. HUBBELL

On a day bristling with important news, the criminal indictment of the “star” witness against President Biden and Hunter Biden in the impeachment inquiry was a watershed moment for the truth. Per the indictment, the GOP’s primary source of allegations of corruption against President Biden lied to FBI agents, concocting a fiction for MAGA media outlets and politicians eager to spread slanderous statements.

The revelation that the “impeachment inquiry” against Biden was built on a house of lies comes hard on the heels of an admission from one of the primary proponents of the 2020 election fraud conspiracy theory that it has no evidence to support its allegations of widespread fraud!

Together, the false stories of “Biden’s corruption” and “election fraud” were major components of the GOP playbook in the 2024 presidential election. Those narratives have now collapsed in a spectacular implosion. That collapse is good for President Biden politically—but the immediate political ramification is not the most important point.

The major takeaway is this: The Republican party is built on lies and sustains itself through lies. They know it. We know it. The media knows it. But now, we have proof that the bad-faith headlines, breathless “whataboutism,” and lazy “both-siderism” of the media are part of a disinformation campaign that must stop.

These twin developments are a watershed moment for the truth.

Let’s take a look.

DOJ indicts FBI informant who was the primary source for allegations of corruption against Joe Biden.

The House “impeachment” inquiry has been a conspiracy theory in search of evidence from the start. House Oversight Chair James Comer took testimony from disgruntled IRS agents with no personal knowledge (but plenty of opinions) and from Hunter Biden’s business partner, who said Joe Biden never participated in his son’s business dealings.

Desperate for proof, Republicans turned to a confidential source, Alexander Smirnov, who claimed to have personal knowledge of alleged bribery ($5 million) by then former Vice President Biden arising from Hunter Biden’s involvement in a Ukrainian energy company (“Burisma”).

On Thursday, a grand jury in the Central District of California issued an indictment against Smirnov for lying to the FBI. The indictment is here: US v. Smirnov | Indictment No. 2:24-CR-00091-ODW. For a summary of the indictment and related details, see NYTimes, Ex-F.B.I. Informant Is Charged With Lying Over Bidens’ Role in Ukraine Business.

Per the Times,

The longtime informant, Alexander Smirnov, 43, is accused of falsely telling the F.B.I. that Hunter Biden, then a paid board member of the energy giant Burisma, demanded the money to protect the company from an investigation by the country’s prosecutor general at the time.

Importantly, the indictment alleges a political motivation for Smirnov to lie about Biden:

Mr. Smirnov’s motivation for lying, prosecutors wrote, appears to have been political. During the 2020 campaign, he sent his F.B.I. handler “a series of messages expressing bias” against Joseph R. Biden Jr., including texts, replete with typos and misspellings, boasting that he had information that would put him in jail.

Smirnov’s allegations were demonstrably false, as explained by the Times:

In 2015 or 2016, Hunter Biden promised to protect the company “through his dad, from all kinds of problems,” Mr. Smirnov falsely claimed to his bureau handler in 2020, according to Mr. Weiss, who has charged the president’s son twice over the past year on tax and gun charges.

This claim was easily disproved, prosecutors said: Mr. Smirnov was only in contact with Burisma executives in 2017, after Mr. Biden left office — when he “had no ability to influence U.S. policy.”

Mr. Smirnov told F.B.I. investigators that he had seen footage of Hunter Biden entering a hotel in Kyiv, Ukraine, that was “wired” by the Russians, suggesting that Russia may have recorded phone calls made by Mr. Biden from the hotel, according to the indictment.

But Mr. Biden had never been to Ukraine, let alone that hotel, prosecutors wrote.

Importantly, the indictment was obtained by special counsel David C. Weiss, who was appointed by Merrick Garland to investigate Hunter Biden. Weiss—who was first appointed as a US Attorney by Donald Trump—has obtained two indictments against Hunter Biden for gun possession and tax evasion charges.

The fact that Smirnov was indicted by the special counsel appointed to investigate Hunter Biden rebuts any notion that the indictment is politically motivated.

Smirnov’s false statements provided the only substantive allegations in the sham “impeachment inquiry” in the House and received massive coverage by an eager news media (especially on Fox News). Those news organizations should retract or correct their previous reporting. It is not enough to report on the indictment of Smirnov.

The most important point is that the GOP’s narrative of a “Biden crime family” is a fiction based on perjured statements provided to the FBI! Tell a friend!

[MORE]

#Robert B. Hubbell Newsletter#Robert B. Hubbell#sham impeachment inquiry#corrupt GOP#corrupt House GOP#Ukraine#Smirnov#Smirnov's false statements

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Former President Donald J. Trump and 18 others, including Rudolph W. Giuliani and Mark Meadows, face conspiracy charges related to attempts to overturn the state’s results and subvert the will of voters

Former President Donald J. Trump and 18 others, including some of his former lawyers and top aides, have been indicted by an Atlanta grand jury in a sweeping racketeering case focused on Mr. Trump’s efforts to reverse the results of the 2020 election in Georgia.

The indictment — handed up after a single, extra-long day of testimony — is an unprecedented challenge of presidential misconduct by a local prosecutor. It brings charges against some of his most prominent advisers, including Rudolph W. Giuliani, his former personal lawyer, and Mark Meadows, who served as White House chief of staff at the time of the election.

[...]

The investigation was led by Fani T. Willis, the Fulton County district attorney. It focused on five actions taken by Mr. Trump or his allies in the weeks after Election Day, when Joseph R. Biden Jr. narrowly won Georgia. Those actions include phone calls that Mr. Trump made to pressure state officials to overturn the result, as well as harassment of local election workers by Trump supporters, false claims of ballot fraud, a plan by Trump allies to create a slate of bogus electors and a data breach at an elections office in rural Coffee County, Ga.

[...]

Kenneth Chesebro and John Eastman, architects of the plan to use fake Trump electors to circumvent the popular vote in a number of swing states, were among a number of lawyers who advised Mr. Trump who were indicted. So was Mike Roman, a former Trump campaign aide who helped coordinate the elector scheme.

Jeffrey Clark, a former senior official in the Department of Justice who embraced false claims about the election and tried to embroil the department in challenging the Georgia vote, was also indicted. Other lawyers who aided Mr. Trump’s efforts who were indicted include Sidney Powell and Jenna Ellis.

A number of Georgia Republicans were also indicted, including David Shafer, the former head of the state party, and Shawn Still, a state senator. Cathy Latham, a party leader in a rural county who served as one of the bogus Trump electors, was also indicted.

All 19 defendants are being charged under Georgia’s racketeering statute, and each of them has at least one additional charge. Racketeering laws are often used to prosecute people involved in patterns of illegal activity, and can be useful in targeting both foot soldiers and leaders in a corrupt organization.

#trump#georgia indictment#19 people were indicted#fani willis#mark meadows#rudi giuliani#the new york times

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Heaven gained a Nobel Peace Prize winning angel yesterday

“Henry A. Kissinger, the scholar-turned-diplomat who engineered the United States’ opening to China, negotiated its exit from Vietnam, and used cunning, ambition and intellect to remake American power relationships with the Soviet Union at the height of the Cold War, sometimes trampling on democratic values to do so, died on Wednesday at his home in Kent, Conn. He was 100.

(…)

Few diplomats have been both celebrated and reviled with such passion as Mr. Kissinger. Considered the most powerful secretary of state in the post-World War II era, he was by turns hailed as an ultrarealist who reshaped diplomacy to reflect American interests and denounced as having abandoned American values, particularly in the arena of human rights, if he thought it served the nation’s purposes.

He advised 12 presidents — more than a quarter of those who have held the office — from John F. Kennedy to Joseph R. Biden Jr. With a scholar’s understanding of diplomatic history, a German-Jewish refugee’s drive to succeed in his adopted land, a deep well of insecurity and a lifelong Bavarian accent that sometimes added an indecipherable element to his pronouncements, he transformed almost every global relationship he touched.

(…)

Mr. Kissinger’s secret negotiations with what was then still called Red China led to Nixon’s most famous foreign policy accomplishment. Intended as a decisive Cold War move to isolate the Soviet Union, it carved a pathway for the most complex relationship on the globe, between countries that at Mr. Kissinger’s death were the world’s largest (the United States) and second-largest economies, completely intertwined and yet constantly at odds as a new Cold War loomed.

For decades he remained the country’s most important voice on managing China’s rise, and the economic, military and technological challenges it posed. He was the only American to deal with every Chinese leader from Mao to Xi Jinping. In July, at age 100, he met Mr. Xi and other Chinese leaders in Beijing, where he was treated like visiting royalty even as relations with Washington had turned adversarial.

He drew the Soviet Union into a dialogue that became known as détente, leading to the first major nuclear arms control treaties between the two nations. With his shuttle diplomacy, he edged Moscow out of its standing as a major power in the Middle East, but failed to broker a broader peace in that region.

Over years of meetings in Paris, he negotiated the peace accords that ended the American involvement in the Vietnam War, an achievement for which he shared the 1973 Nobel Peace Prize. He called it “peace with honor,” but the war proved far from over, and critics argued that he could have made the same deal years earlier, saving thousands of lives.

(…)

As was the case with Vietnam, history has judged some of his Cold War realism in a harsher light than it was generally portrayed at the time. With an eye fixed on the great power rivalry, he was often willing to be crudely Machiavellian, especially when dealing with smaller nations that he often regarded as pawns in the greater battle.

He was the architect of the Nixon administration’s efforts to topple Chile’s democratically elected Socialist president, Salvador Allende.

He has been accused of breaking international law by authorizing the secret carpet-bombing of Cambodia in 1969-70, an undeclared war on an ostensibly neutral nation.

His objective was to root out the pro-Communist Vietcong forces that were operating from bases across the border in Cambodia, but the bombing was indiscriminate: Mr. Kissinger told the military to strike “anything that flies or anything that moves.” At least 50,000 civilians were killed.

When Pakistan’s U.S.-backed military was waging a genocidal war in East Pakistan, now Bangladesh, in 1971, he and Nixon not only ignored pleas from the American consulate in East Pakistan to stop the massacre, but they approved weapons shipments to Pakistan, including the apparently illegal transfer of 10 fighter-bombers from Jordan.

Mr. Kissinger and Nixon had other priorities: supporting Pakistan’s president, who was serving as a conduit for Kissinger’s then-secret overtures to China. Again, the human cost was horrific: At least 300,000 people were killed in East Pakistan and 10 million refugees were driven into India.

In 1975, Mr. Kissinger and President Ford secretly approved the invasion of the former Portuguese colony of East Timor by Indonesia’s U.S.-backed military. After the loss of Vietnam, there were fears that East Timor’s leftist government could also go Communist.

Mr. Kissinger told Indonesia’s president that the operation needed to succeed quickly and that “it would be better if it were done after we returned” to the United States, according to declassified documents from Mr. Ford’s presidential library. More than 100,000 East Timorese were killed or starved to death.

Mr. Kissinger dismissed critics of these moves by saying that they did not face the world of bad choices he did. But his efforts to snuff out criticism with sarcastic one-liners only inflamed it.

“The illegal we do immediately,” he quipped more than once. “The unconstitutional takes a little longer.”

On at least one potentially catastrophic stance Mr. Kissinger later reversed himself.

Starting in the mid-1950s as a young Harvard professor, he argued for the concept of limited nuclear war — a nuclear exchange that could be contained to a specific region. In office, he worked extensively on nuclear deterrence — convincing an adversary, for instance, that there was no way to launch a nuclear strike without paying an unacceptably high price.

(…)

“We dropped more ordnance on Cambodia and Laos than on Europe in World War II,” Mr. Obama said in an interview with The Atlantic in 2016, “and yet, ultimately, Nixon withdrew, Kissinger went to Paris, and all we left behind was chaos, slaughter and authoritarian governments that finally, over time, have emerged from that hell.”

(…)

Few figures in modern American history remained so relevant for so long as Mr. Kissinger. Well into his 90s he kept speaking and writing, and charging astronomical fees to clients seeking his geopolitical analysis.

While the protesters at his talks dwindled, the very mention of his name could trigger bitter arguments. To his admirers, he was the brilliant architect of Pax Americana, the chess grandmaster who was willing to upend the board and inject a measure of unpredictability into American diplomacy.

To his detractors — and even some friends and former employees — he was vain, conspiratorial, arrogant and short-tempered, a man capable of praising a top aide as indispensable while ordering the F.B.I. to illegally tap his home phones to see if he was leaking to the press.

(…)

To read Mr. Kissinger’s laudatory 1957 book analyzing the world order created by Prince Klemens von Metternich of Austria, who led the Austrian empire in the post-Napoleonic era, is also to read something of a self-description, particularly when it came to the ability of a single leader to bend nations to his will.

“He excelled at manipulation, not construction,” Mr. Kissinger said of Metternich. “He preferred the subtle maneuver to the frontal attack.”

(…)

In the spring of 1969, soon after taking office, he was so enraged by the leaks behind a Times report on the Cambodia bombing campaign that he ordered the F.B.I. to tap the phones of more than a dozen White House aides, including members of his own staff. The recordings never turned up a culprit.

He was similarly infuriated by the publication of the Pentagon Papers in The Times and The Washington Post in 1971. The classified documents chronicled the government’s war policies and planning in Vietnam, and leaking them, in his view, jeopardized his secret face-to-face diplomacy. His complaints helped inspire the creation of the White House burglary team, the leak-plugging Plumbers unit that would later break into Democratic headquarters at the Watergate building.

(…)

Aides described his insights as brilliant and his temper ferocious. They told stories of Mr. Kissinger throwing books across his office in towering rages, and of a manipulative streak that led even his most devoted associates to distrust him.

“In dealing with other people he would forge alliances and conspiratorial bonds by manipulating their antagonisms,” Walter Isaacson wrote in his comprehensive 1992 biography, “Kissinger,” a book its subject despised.

“Drawn to his adversaries with a compulsive attraction, he would seek their approval through flattery, cajolery and playing them off against others,” Mr. Isaacson observed. “He was particularly comfortable dealing with powerful men whose minds he could engage. As a child of the Holocaust and a scholar of Napoleonic-era statecraft, he sensed that great men as well as great forces were what shaped the world, and he knew that personality and policy could never be fully divorced. Secrecy came naturally to him as a tool of control. And he had an instinctive feel for power relationships and balances, both psychological and geostrategic.”

(…)

There was something fundamentally simple, if terrifying, in the superpower conflicts he navigated. He never had to deal with terrorist groups like Al Qaeda or the Islamic State, or a world in which nations use social media to manipulate public opinion and cyberattacks to undermine power grids and communications.

“The Cold War was more dangerous,” Mr. Kissinger said in a 2016 appearance at the New-York Historical Society. “Both sides were willing to go to general nuclear war.” But, he added, “today is more complex.”

The great-power conflict had changed dramatically from the cold peace he had tried to engineer. No longer ideological, it was purely about power. And what worried him most, he said, was the prospect of conflict with “the rising power” of China as it challenged the might of the United States.

(…)

Mr. Kissinger took some satisfaction in the fact that Russia was a lesser threat. After all, he had concluded the first strategic arms agreement with Moscow and steered the United States toward accepting the Helsinki Accords, the 1975 compact on European security that obtained some rights of expression for Soviet bloc dissidents. In retrospect, it was one of the droplets that turned into the river that swept away Soviet Communism.

(…)

“It’s almost impossible to imagine what the American relationship with the world’s most important rising power would look like today without Henry,” Graham Allison, a Harvard professor who once worked for Mr. Kissinger, said in an interview in 2016.

Other Kissinger efforts yielded mixed results. Through tireless shuttle diplomacy at the end of the Yom Kippur War in 1973, Mr. Kissinger was able to persuade Egypt to begin direct talks with Israel, an opening wedge to the later peace agreement between the two nations.

But perhaps the most important diplomatic contribution Mr. Kissinger made was his sidelining of Moscow in the Middle East for four decades, until Mr. Putin ordered his air force to enter the Syrian civil war in 2015.

(…)

“For the formative years of his youth, he faced the horror of his world coming apart, of the father he loved being turned into a helpless mouse,” said Fritz Kraemer, a non-Jewish German immigrant who was to become Mr. Kissinger’s first intellectual mentor. “It made him seek order, and it led him to hunger for acceptance, even if it meant trying to please those he considered his intellectual inferiors.”

Some have argued that Mr. Kissinger’s rejection of a moralistic approach to diplomacy in favor of realpolitik arose because he had borne witness to a civilized Germany embracing Hitler. Mr. Kissinger often cited an aphorism of Goethe’s, saying that if he were given the choice of order or justice, he, like the novelist and poet, would prefer order.

(…)

Heinz became Henry in high school. He switched to night school when he took a job at a company making shaving brushes. In 1940, he enrolled in City College — tuition was virtually free — and racked up A’s in almost all his courses. He seemed headed to becoming an accountant.

Then, in 1943, he was drafted into the Army and assigned to Camp Claiborne in Louisiana.

It was there that Mr. Kraemer, a patrician intellectual and Prussian refugee, arrived one day to give a talk about the “moral and political stakes of the war,” as Mr. Kissinger recalled. The private returned to his barracks and wrote Mr. Kraemer a note: “I heard you speak yesterday. This is how it should be done. Can I help you in any way?”

The letter changed the direction of his life. Taking him under his wing, Mr. Kraemer arranged for Private Kissinger to be reassigned to Germany to serve as a translator. As German cities and towns fell in the last months of the war, Mr. Kissinger was among the first on the scene, interrogating captured Gestapo officers and reading their mail.

In April 1945, with Allied victory in sight, he and his fellow soldiers led raids on the homes of Gestapo members who were suspected of planning sabotage campaigns against the approaching American forces. For his efforts he received a Bronze Star.

But before returning to the United States he visited Fürth, his hometown, and found that only 37 Jews remained. In a letter discovered by Niall Ferguson, his biographer, Mr. Kissinger wrote at 23 that his encounters with concentration camp survivors had taught him a key lesson about human nature.

“The intellectuals, the idealists, the men of high morals had no chance,” the letter said. The survivors he met “had learned that looking back meant sorrow, that sorrow was weakness, and weakness synonymous with death.”

Mr. Kissinger stayed in Germany after the war — fearful, he said later, that the United States would succumb to a democracy’s temptation to withdraw its weary forces too fast and lose the chance to cement victory.

He took a job as a civilian instructor teaching American officers how to uncover former Nazi officers, work that allowed him to crisscross the country. He became alarmed by what he saw as Communist subversion of Germany and warned that the United States needed to monitor German phone conversations and letters. It was his first taste of a Cold War that he would come to shape.

(…)

But the outsider now had direction, and he found another mentor in William Yandell Elliott, who headed the government department. Professor Elliott guided Mr. Kissinger toward political theory, even as he wrote privately that his student’s mind “lacks grace and is Teutonic in its systematic thoroughness.”

Under Professor Elliott, Mr. Kissinger wrote a senior thesis, “The Meaning of History,” focusing on Immanuel Kant, Oswald Spengler and Arnold Toynbee. At a hefty 383 pages, it gave rise to what became informally known at Harvard as “the Kissinger rule,” which limits the length of a senior thesis.

(…)

Returning to Harvard to pursue a Ph.D., he and Professor Elliott started the Harvard International Seminar, a project that brought young foreign political figures, civil servants, journalists and an occasional poet to the university.

The seminar placed Mr. Kissinger at the center of a network that would produce a number of leaders in world affairs, among them Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, who would become president of France; Yasuhiro Nakasone, a future prime minister of Japan; Bulent Ecevit, later the longtime prime minister of Turkey; and Mahathir Mohamad, the future father of modern Malaysia.

With Ford Foundation support, the seminar kept his family eating as Mr. Kissinger worked on his dissertation on the diplomacy of Metternich of Austria and Robert Stewart Castlereagh, the British foreign secretary, after the Napoleonic wars. The dissertation, which became his first book, both shaped and reflected his view of the modern world.

The book, “A World Restored,” can be read as a guide to Mr. Kissinger’s later fascination with the balancing of power among states and his suspicion of revolutions. Metternich and Mr. Castlereagh sought stability in Europe and largely achieved it by containing an aggressive revolutionary France through an equilibrium of forces.

Mr. Kissinger saw parallels in the great struggle of his time: containing Stalin’s Soviet Union.

“His was a quest for a realpolitik devoid of moral homilies,” Stanley Hoffmann, a Harvard colleague who later split with Mr. Kissinger, said in 2015.

Mr. Kissinger received his Ph.D. in 1954 but received no offer of an assistant professorship. Some on the Harvard faculty complained that he had not poured himself into his work as a teaching fellow. They regarded him as too engaged in worldly issues. In fact, he was simply ahead of his time: The Boston-to-Washington corridor would soon become jammed with academics consulting with the government or lobbyists.

The Harvard rejection embittered Mr. Kissinger. The Nixon tapes later caught him telling the president that the problem with academia was that “you are entirely dependent on the personal recommendation of some egomaniac.”

With the help of McGeorge Bundy, a Harvard colleague, Mr. Kissinger was placed in an elite study group at the Council on Foreign Relations, at the time a stuffy, all-male enclave in New York. Its mission was to study the impact of nuclear weapons on foreign policy.

Mr. Kissinger arrived in New York with a lot of attitude. He thought that the Eisenhower administration was wrongly reluctant to rethink American strategic policy in light of Moscow’s imminent ability to strike the United States with overwhelming nuclear force.

“Henry managed to convey that no one had thought intelligently about nuclear weapons and foreign policy until he came along to do it himself,” Paul Nitze, perhaps the country’s leading nuclear strategist at the time, later told Strobe Talbott, who was deputy secretary of state under President Bill Clinton.

Mr. Kissinger seized on a question that Mr. Nitze had begun discussing: whether America’s threat to go to general nuclear war against the Soviet Union was no longer credible given the commonly held view that any such conflict would invite only “mutually assured destruction.” Mr. Nitze asked whether it would be wiser to develop weapons to conduct a limited, regional nuclear war.

Mr. Kissinger decided that “limited nuclear war represents our most effective strategy.”

What was supposed to be a council publication became instead a Kissinger book, and his first best seller: “Nuclear Weapons and Foreign Policy.” Its timing, 1957, was perfect: It played into a national fear of growing Soviet power.

And its message fit the moment: If an American president was paralyzed by fear of escalation, Mr. Kissinger argued, the concept of nuclear deterrence would fail. If the United States could not credibly threaten to use small, tactical weapons, he said, it “would amount to giving the Soviet rulers a blank check.” In short, professing a willingness to conduct a small nuclear war was better than risking a big one.

To his critics, this was Mr. Kissinger at his Cold War worst, weaving an argument that a nuclear exchange could be won. Many scholars panned the book, believing its 34-year-old author had overestimated the nation’s ability to keep limited war limited. But to the public it was a breakthrough in nuclear thinking. To this day it is considered a seminal work, one that scholars now refer to in looking for lessons to apply to cyberwarfare.

(…)

David Riesman, the sociologist and co-author of a seminal work on the American character, “The Lonely Crowd,” suggested that dinner with Mr. Kissinger was a chore. “He would not spend time chatting at the table,” Mr. Riesman said. “He presided.”

Leslie H. Gelb, then a doctoral student and later a Pentagon official and columnist for The Times, called him “devious with his peers, domineering with his subordinates, obsequious to his superiors.”

(…)

At Harvard, he began organizing meetings on the emerging crisis of the day, Vietnam. He explored the link between military actions on the ground and the chances of success through diplomacy, seemingly convinced, even then, that the war could be ended only through negotiations.

After a long trip to Saigon and the front lines, he wrote that the American task was to “build a nation in a divided society in the middle of a civil war,” defining a problem that would haunt Washington not only in Southeast Asia but also in Afghanistan and Iraq.

(…)

With Lyndon B. Johnson’s White House engaged in peace talks with the North Vietnamese in Paris, Mr. Kissinger was said to have used his contacts on his own trips to Paris to funnel inside information back to Nixon. “Henry was the only person outside the government we were authorized to discuss the negotiation with,” Richard C. Holbrooke, who went on to key positions in the Clinton and Obama administrations, told Mr. Isaacson for his Kissinger biography. “We trusted him. It is not stretching the truth to say that the Nixon campaign had a secret source within the United States negotiating team.”

Nixon himself referred in his memoirs to his “highly unusual channel” of information. To many who have since accepted that account, the back-channel tactic was evidence of Mr. Kissinger’s drive to obtain power if Nixon was elected. While there is no evidence that he supplied classified information to the Nixon campaign, there have long been allegations that Nixon used precisely that to give back-channel assurances to the South Vietnamese that they would get a better deal from him than from Johnson, and that they should agree to nothing until after the election.

Mr. Ferguson and other historians have rebutted that claim, though one of Nixon’s biographers found notes from H.R. Haldeman, one of Nixon’s closest aides, in which the presidential candidate ordered his staff to “monkey wrench” peace talks.

Whatever the truth, Mr. Kissinger was on Nixon’s radar. And after the election, a new president who had often expressed his disdain for Jews and Harvard academics chose, as his national security adviser, a man who was both.

Nixon directed Mr. Kissinger to run national security affairs covertly from the White House, cutting out the State Department and Nixon’s secretary of state, William P. Rogers. Nixon had found his man — a “prized possession,” he later called Mr. Kissinger.

While the post of national security adviser had grown in importance since Harry S. Truman established the role, Mr. Kissinger took it to new heights. He recruited bright young academics to his staff, which he nearly doubled. He effectively sidelined Mr. Rogers and battled the pugnacious defense secretary, Melvin R. Laird, moving more decision-making into the White House.

(…)

Staff turnover was high, but many of those who stayed came to admire him for his intellect and his growing list of achievements. Still, they were stunned by his secretiveness. “He was able to give a conspiratorial air to even the most minor of things,” Mr. Eagleburger, who admired him, said before his death in 2011.

Poking fun at himself in a way that some saw as disingenuous, he often told visiting diplomats that “I have not faced such a distinguished audience since dining alone in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles.”

Nixon had built much of his campaign around the promise to end the war on honorable terms. It was Mr. Kissinger’s task to turn that promise into a reality, and he made clear in a Foreign Affairs article, published as Nixon was preparing to take office, that the United States would not win the war “within a period or with force levels politically acceptable to the American people.”

In the 2018 interview, he said the United States had misunderstood the struggle from the start as “an extension of the Cold War in Europe.”

“I made the same mistake,” he said. “The Cold War was really about saving democratic countries from invasion.” Vietnam was different, a civil war. “What we did not understand at the beginning of the war in Vietnam,” he went on, “is how hard it is to end these civil wars, and how hard it is to get a conclusive agreement in which everyone shares the objective.”

(…)

Mr. Kissinger’s pursuit of two goals that were seen as at odds with each other — winding down the war and maintaining American prestige — led him down roads that made him a hypocrite to some and a war criminal to others. He had come to office hoping for a fast breakthrough: “Give us six months,” he told a Quaker group, “and if we haven’t ended the war by then, you can come back and tear down the White House fence.”

But six months later, there were already signs that the strategy for ending the war would both expand and lengthen it. He was convinced that the North Vietnamese would enter serious negotiations only under military pressure. So while he restarted secret peace talks in Paris, he and Nixon escalated and widened the war.

“I can’t believe that a fourth-rate power like North Vietnam doesn’t have a breaking point,” Mr. Kissinger told his staff.

Mr. Kissinger called it “war for peace.” Yet the result was carnage. Mr. Kissinger had an opportunity to end the war in peace talks early in Nixon’s presidency on terms as good as those he ultimately settled for later. Yet he turned it down, and thousands of Americans died because he was convinced he could do better.

As Mr. Kissinger sat with his big yellow legal pads in his White House office, scribbling notes that have now been largely declassified, he designed a three-part plan. It consisted of a cease-fire that would also embrace Laos and Cambodia, which had been sucked into the fighting; simultaneous American and North Vietnamese withdrawals from South Vietnam; and a peace treaty that returned all prisoners of war.

His notes and taped conversations with Nixon are riddled with self-assured declarations that the next escalation of bombing, and a secret incursion into Cambodia, would break the North Vietnamese and force them into real negotiations. But he was also reacting, he later wrote, to a Vietcong and North Vietnamese offensive early in Nixon’s presidency that had killed almost 2,000 Americans and “humiliated the new president.”

Mr. Kissinger later constructed a narrative emphasizing the wisdom of the strategy, but the notes and phone conversations suggest that he had routinely overestimated his negotiating skills and underestimated his opponents’ capacity to wait the Americans out.

It was the bombing campaign in Cambodia — code-named “Operation Menu,” with phases named “Breakfast,” “Lunch” and “Dinner” — that outraged Mr. Kissinger’s critics and fueled books, documentaries and symposiums exploring whether the United States had violated international law by expanding the conflict into a country that was not party to the war. Mr. Kissinger’s rationale was that the North had created supply lines through Cambodia to fuel the war in the South.

(…)

It took until January 1973 for Mr. Kissinger to reach a deal, assuring the South Vietnamese that the United States would return if the North violated the accord and invaded. Privately, Mr. Kissinger was all but certain that the South could not hold up under the pressure. He told John D. Erlichman, a top White House aide, that “if they are lucky, they can hold out for a year and a half.”

That proved prescient: Saigon fell in April 1975, with the unconditional surrender of South Vietnam. Fifty-eight thousand Americans and more than three million North and South Vietnamese had died, and eight million tons of bombs had been dropped by the United States. But to Mr. Kissinger, getting it over with was the key to moving on to bigger, and more successful, ventures.

When Mr. Kissinger was writing campaign speeches for Nelson Rockefeller in 1968, he included a passage in which he envisioned “a subtle triangle with Communist China and the Soviet Union.” The strategy, he wrote, would allow the United States to “improve our relations with each as we test the will for peace of both.”

He got a chance to test that thesis the next year. Chinese and Soviet forces had clashed in a border dispute, and in a meeting with Mr. Kissinger, Anatoly F. Dobrynin, the Soviet ambassador to Washington, spoke candidly of the importance of “containing” the Chinese. Nixon directed Mr. Kissinger to make an overture, secretly, to Beijing.

It was a remarkable shift for Nixon. A staunch anti-Communist, he had long had close ties to the so-called China lobby, which opposed the Communist government led by Mao Zedong in Beijing. He also believed that North Vietnam was acting largely as a Chinese satellite in its war against South Vietnam and its American allies.

Nixon and Mr. Kissinger secretly approached Pakistan’s leader, Yahya Khan, to act as a go-between. In December 1970, Pakistan’s ambassador in Washington delivered a message to Mr. Kissinger that had been carried from Islamabad by courier. It was from the Chinese prime minister, Zhou Enlai: A special envoy from President Nixon would be welcome in Beijing.

(…)

Over the next two months, messages were exchanged concerning a possible presidential visit. Then, on June 2, 1971, Mr. Kissinger received one more communication through the Pakistani connection, this one inviting him to Beijing to prepare for a Nixon visit. Mr. Kissinger pulled Nixon aside from a White House dinner to declare: “This is the most important communication that has come to an American president since the end of World War II.”

(…)

In Beijing he made a presentation to Mr. Zhou, ending with the observation that as Americans “we find ourselves here in what to us is a land of mystery,” he recalled in a 2014 interview for the Harvard Secretaries of State project. Mr. Zhou interrupted. “There are 900 million of us,” he said, “and it’s not mysterious to us.”

It took three days to work out the details, and after Mr. Kissinger cabled the code word “eureka” to Nixon, the president, without any advance warning, appeared on television to announce what Mr. Kissinger had arranged. His enemies — the Soviets, the North Vietnamese, the Democrats, his liberal critics — were staggered. On Feb. 21, 1972, he became the first American president to visit mainland China.

The Chinese were a little stunned, too. Mao sidelined Mr. Zhou within a month. After that, no Chinese ever mentioned Zhou Enlai again, Mr. Kissinger told the Harvard project. He speculated that Mao had feared that his No. 2 “was getting personally too friendly with me.”

(…)

“That China and the United States would find a way to come together was inevitable given the necessities of the time,” he wrote in “On China,” referring to domestic strife in both countries and a common interest in resisting Soviet advances. But he also insisted that he had not been seeking to isolate Russia as much as to conduct a grand experiment in balance-of-power politics. “Our view,” he wrote, “was that the existence of the triangular relations was in itself a form of pressure on each of them.”

Historians still debate whether that worked. But there is no debating that it made Mr. Kissinger an international celebrity. It also proved vital for reasons that never factored into Mr. Kissinger’s calculus five decades ago — that China would rise as the only true economic, technological and military competitor to the United States.

Nixon’s announcement that he would go to China startled Moscow. Days later, Mr. Dobrynin called on Mr. Kissinger and invited Nixon to meet the Soviet leader, Leonid I. Brezhnev, in the Kremlin. The date was set for May 1972, just three months after the China trip. “To have two Communist powers competing for good relations with us could only benefit the cause of peace,” Mr. Kissinger noted later. “It was the essence of triangular strategy.”

To prepare for the summit, he flew to Moscow, again in secret. Nixon had agreed to let him go on the condition that Mr. Kissinger spend most of his time insisting that the Soviets restrain their North Vietnamese allies, who were mounting an offensive.

By then, however, Mr. Kissinger had changed his mind about how much control the Soviets had over the North Vietnamese, writing to his deputy, Alexander M. Haig, “I do not believe that Moscow is in direct collusion with Hanoi.”

Instead, he sought to reinvigorate negotiations, which had been stumbling along since late 1969, with the aim of limiting the number of ground-based and submarine-launched nuclear missiles that the two countries were pointing at each other and curbing the development of antiballistic missile systems. Mr. Kissinger achieved a breakthrough, writing to Nixon, “You will be able to sign the most important arms control agreement ever concluded.”

That may have been overstatement, but Mr. Brezhnev and Nixon signed what became the SALT I treaty in May 1972. It opened decades of arms-control agreements — SALT, START, New START — that greatly reduced the number of nuclear weapons in the world. The era known as détente had begun. It unraveled only late in Mr. Kissinger’s life. While Mr. Putin and Mr. Biden renewed New START in 2021, once the war in Ukraine started the Russian leader suspended compliance with many parts of the treaty.

To Mr. Kissinger, there were superpowers and there was everything else, and it was the everything else that got him into trouble.

He never stopped facing questions about the overthrow and death of Mr. Allende in Chile in September 1973 and the rise of Augusto Pinochet, the general who had seized power.

Over the next three decades, as General Pinochet came to be accused — first in Europe, then in Chile — of abductions, murder and human rights violations, Mr. Kissinger was repeatedly linked to clandestine activities that had undermined Mr. Allende, a Marxist, and his democratically elected government. The revelations emerged in declassified documents, lawsuit depositions and journalistic indictments, like Christopher Hitchens’s book “The Trial of Henry Kissinger” (2001), which was made into a documentary film.

(…)

Nixon, too, was alarmed, according to a White House tape that Peter Kornbluh, of the National Security Archive, cited in his book “The Pinochet File: A Declassified Dossier on Atrocity and Accountability.” It quotes Nixon as ordering the U.S. ambassador in Santiago “to do anything short of a Dominican-type action” to keep Mr. Allende from winning the election. The reference was to the United States invasion of the Dominican Republic in 1965.

Mr. Kissinger insisted, in a memoir and in testimony to Congress, that the United States “had nothing to do” with the military coup that overthrew Mr. Allende. However according to phone records that were declassified in 2004, Mr. Kissinger bragged that “we helped them” by creating the conditions for the coup.

That help included backing a plot to kidnap the commander in chief of Chile’s army, Gen. René Schneider, who had refused C.I.A. entreaties to mount a coup. The general was killed in the attempt. His car was ambushed, and he was fatally shot at point-blank range.

(…)

In 2001, General Schneider’s two sons filed a civil suit in the United States accusing Mr. Kissinger of helping to orchestrate covert activities in Chile that led to their father’s death. A U.S. federal court, without ruling on Mr. Kissinger’s culpability, dismissed the case, saying that foreign policy was up to the government, not the courts.

Mr. Kissinger, in his defense, said his actions had to be viewed within the context of the Cold War. “I don’t see why we need to stand by and watch a country go Communist due to the irresponsibility of its people,” he said, adding half-jokingly: “The issues are much too important for the Chilean voters to be left to decide for themselves.”

Chile was hardly the only place Mr. Kissinger was accused of treating as a minor chess piece in his grand strategies. He and President Ford approved Indonesia’s invasion of East Timor in December 1975, leading to a disastrous 24-year occupation by a U.S.-backed military.

Declassified documents released in 2001 by the National Security Archive indicate that Ford and Mr. Kissinger knew of the invasion plans months in advance and were aware that the use of American arms would violate U.S. law.

“I know what the law is,” Mr. Kissinger was quoted as telling a staff meeting when he got back to Washington. He then asked how it could be in “U.S. national interest” for Americans to “kick the Indonesians in the teeth?”

The columnist Anthony Lewis wrote in The Times, “That was Kissingerian realism: the view that the United States should overlook brutalities by friendly authoritarian regimes because they provided ‘stability.’”

It was a familiar complaint. In 1971, the slaughter in East Pakistan that Nixon and Mr. Kissinger had ignored in deference to Pakistan expanded into a war between Pakistan and India, a nation loathed by both China and the Nixon White House.

“At this point, the recklessness of Nixon and Kissinger only got worse,” Dexter Filkins, of The New Yorker, wrote in discussing Professor Bass’s account in The New York Times Book Review in 2013. “They dispatched ships from the Seventh Fleet into the Bay of Bengal, and even encouraged China to move troops to the Indian border, possibly for an attack — a maneuver that could have provoked the Soviet Union. Fortunately, the leaders of the two Communist countries proved more sober than those in the White House. The war ended quickly, when India crushed the Pakistani Army and East Pakistan declared independence,” becoming the new nation of Bangladesh.

(…)

Still more declassified documents revealed how Mr. Kissinger had used his historic 1971 meeting with Mr. Zhou in China to lay out a radical shift in American policy toward Taiwan. Under the plan, the United States would have essentially abandoned its support for the anticommunist Nationalists in Taiwan in exchange for China’s help in ending the war in Vietnam. The account contradicted one he had included in his published memoirs.

The emerging material also revealed the price of an American-interests-first realism. In tapes released by the Nixon Presidential Library and Museum in 2010, Mr. Kissinger is heard telling Nixon in 1973 that helping Soviet Jews emigrate and thus escape oppression by a totalitarian regime was “not an objective of American foreign policy.”

“And if they put Jews into gas chambers in the Soviet Union,” he added, “it is not an American concern. Maybe a humanitarian concern.”

The American Jewish Committee described the remarks as “truly chilling,” but suggested that antisemitism in the Nixon White House may have partly been to blame.

“Perhaps Kissinger felt that, as a Jew, he had to go the extra mile to prove to the president that there was no question as to where his loyalties lay,” David Harris, the committee’s executive director, said.

(…)

Mr. Kissinger was aware of his contentious place in American history, and he may have had his own standing in mind when, in 2006, he wrote about Dean Acheson, secretary of state under Truman, in The Times Book Review, calling him “perhaps the most vilified secretary of state in modern American history.”

“History has treated Acheson more kindly,” Mr. Kissinger wrote. “Accolades for him have become bipartisan.”

Thirty-five years after his death, he said, Acheson had “achieved iconic status.”

(…)

One student asked him about his legacy. “You know, when I was young, I used to think of people of my age as a different species,” he said to laughter. “And I thought my grandparents had been put into the world at the age at which I experienced them.”

“Now that I’ve reached beyond their age,” he added, “I’m not worried about my legacy. And I don’t give really any thought to it, because things are so changeable. You can only do the best you’re able to do, and that’s more what I judge myself by — whether I’ve lived up to my values, whatever their quality, and to my opportunities.””

youtube

#kissinger#henry kissinger#diplomacy#nixon#richard nixon#ford#gerald ford#mao#zhou enlai#china#chile#allende#vietnam#cambodia#nelson rockefeller#nuclear weapons#nuclear strategy#nobel peace prize#realpolitik#metternich#cold war#soviet union#monty python#Youtube

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Proclamation on Indigenous Peoples’ Day, 2021

Since time immemorial, American Indians, Alaska Natives, and Native Hawaiians have built vibrant and diverse cultures — safeguarding land, language, spirit, knowledge, and tradition across the generations. On Indigenous Peoples’ Day, our Nation celebrates the invaluable contributions and resilience of Indigenous peoples, recognizes their inherent sovereignty, and commits to honoring the Federal Government’s trust and treaty obligations to Tribal Nations.

Our country was conceived on a promise of equality and opportunity for all people — a promise that, despite the extraordinary progress we have made through the years, we have never fully lived up to. That is especially true when it comes to upholding the rights and dignity of the Indigenous people who were here long before colonization of the Americas began. For generations, Federal policies systematically sought to assimilate and displace Native people and eradicate Native cultures. Today, we recognize Indigenous peoples’ resilience and strength as well as the immeasurable positive impact that they have made on every aspect of American society. We also recommit to supporting a new, brighter future of promise and equity for Tribal Nations — a future grounded in Tribal sovereignty and respect for the human rights of Indigenous people in the Americas and around the world.

In the first week of my Administration, I issued a memorandum reaffirming our Nation’s solemn trust and treaty obligations to American Indian and Alaska Native Tribal Nations and directed the heads of executive departments and agencies to engage in regular, meaningful, and robust consultation with Tribal officials. It is a priority of my Administration to make respect for Tribal sovereignty and self-governance the cornerstone of Federal Indian policy. History demonstrates that Native American people — and our Nation as a whole — are best served when Tribal governments are empowered to lead their communities and when Federal officials listen to and work together with Tribal leaders when formulating Federal policy that affects Tribal Nations.

The contributions that Indigenous peoples have made throughout history — in public service, entrepreneurship, scholarship, the arts, and countless other fields — are integral to our Nation, our culture, and our society. Indigenous peoples have served, and continue to serve, in the United States Armed Forces with distinction and honor — at one of the highest rates of any group — defending our security every day. And Native Americans have been on the front lines of the COVID-19 pandemic, working essential jobs and carrying us through our gravest moments. Further, in recognition that the pandemic has harmed Indigenous peoples at an alarming and disproportionate rate, Native communities have led the way in connecting people with vaccination, boasting some of the highest rates of any racial or ethnic group.

The Federal Government has a solemn obligation to lift up and invest in the future of Indigenous people and empower Tribal Nations to govern their own communities and make their own decisions. We must never forget the centuries-long campaign of violence, displacement, assimilation, and terror wrought upon Native communities and Tribal Nations throughout our country. Today, we acknowledge the significant sacrifices made by Native peoples to this country — and recognize their many ongoing contributions to our Nation.

On Indigenous Peoples’ Day, we honor America’s first inhabitants and the Tribal Nations that continue to thrive today. I encourage everyone to celebrate and recognize the many Indigenous communities and cultures that make up our great country.

NOW, THEREFORE, I, JOSEPH R. BIDEN JR., President of the United States of America, do hereby proclaim October 11, 2021, as Indigenous Peoples’ Day. I call upon the people of the United States to observe this day with appropriate ceremonies and activities. I also direct that the flag of the United States be displayed on all public buildings on the appointed day in honor of our diverse history and the Indigenous peoples who contribute to shaping this Nation.

IN WITNESS WHEREOF, I have hereunto set my hand this eighth day of October, in the year of our Lord two thousand twenty-one, and of the Independence of the United States of America the two hundred and forty-sixth.

#joe biden#indigenous peoples day#US politics#US history#fuck christopher columbus#USA#united states of america

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Former President Donald J. Trump was indicted on Tuesday in connection with his widespread efforts to overturn the 2020 election following a sprawling federal investigation into his attempts to cling to power after losing the presidency to Joseph R. Biden Jr.

The indictment was filed by the special counsel Jack Smith in Federal District Court in Washington.

It accuses Mr. Trump of three conspiracies: one to defraud the United States, a second to obstruct an official government proceeding and a third to deprive people of civil rights provided by federal law or the Constitution.

“Each of these conspiracies — which built on the widespread mistrust the defendant was creating through pervasive and destabilizing lies about election fraud — targeted a bedrock function of the United States federal government: the nation’s process of collecting, counting and certifying the results of the presidential election,” the indictment said.

The indictment said Mr. Trump had six co-conspirators, but it did not name them.

I am FERAL

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Today, we send a message to all transgender Americans: You are loved. You are heard. You are understood. You belong. You are America, and my entire Administration and I have your back," it continued. "NOW, THEREFORE, I, JOSEPH R. BIDEN JR., President of the United States of America, by virtue of the authority vested in me by the Constitution and the laws of the United States, do hereby proclaim March 31, 2024, as Transgender Day of Visibility."

Joe Biden is a demon. No devout Catholic would do this on Easter. I honestly despise this evil man.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

NOW, THEREFORE, I, JOSEPH R. BIDEN JR., President of the United States of America, by virtue of the authority vested in me by the Constitution and the laws of the United States, do hereby proclaim March 31, 2024, as Transgender Day of Visibility.

Big difference! This is a hit against Christians…it’s so obvious!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

on top of Joe Biden facilitating genocide in Gaza, I also want to call attention to the fact that his statements supporting the Indian government and his policy towards India are essentially condemning almost half a billion people to the genocidal state and right-wing mob terror

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bears repeating:

"NOW, THEREFORE, I, JOSEPH R. BIDEN JR., President of the United States of America, by virtue of the authority vested in me by the Constitution and the laws of the United States, do hereby proclaim March 31, 2024, as Transgender Day of Visibility."

It's on the Whitehouse website. Google the above. Find the proclamation. Skip down to Paragraph six. Apparently Biden is now denying that he ever said it..though it's on the Whitehouse website.

#god is a republican#Rock the vote#Gun control#Culture wars#Easter Sunday#LGBTQI+#donald trump#suck my freedom#kyle rittenhouse#conservatives#make america great again

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Not So Deft on Taiwan"

Words matter, in diplomacy and in law.

Last week [the] President [...] was asked if the United States had an obligation to defend Taiwan if it was attacked by China. He replied, "Yes, we do, and the Chinese must understand that. Yes, I would." [...]

A few hours later, the president appeared to back off this startling new commitment, stressing that he would continue to abide by the "one China" policy followed by each of the past five administrations.

Where once the United States had a policy of "strategic ambiguity" -- under which we reserved the right to use force to defend Taiwan but kept mum about the circumstances in which we might, or might not, intervene in a war across the Taiwan Strait -- we now appear to have a policy of ambiguous strategic ambiguity. It is not an improvement.

The United States has a vital interest in [...] Taiwan [...]

What is the appropriate role for the United States? The president's national security adviser last Wednesday claimed that "the Taiwan Relations Act makes very clear that the U.S. has an obligation that Taiwan's peaceful way of life is not upset by force."

No. Not exactly. The United States has not been obligated to defend Taiwan since we abrogated the 1954 Mutual Defense Treaty signed by President Eisenhower and ratified by the Senate. The Taiwan Relations Act articulates, as a matter of policy, that any attempt to determine the future of Taiwan by other than peaceful means would constitute "a threat to the peace and security of the Western Pacific area" and would be, "of grave concern to the United States."

The act obliges the president to notify Congress in the event of any threat to the security of Taiwan, and stipulates that the president and Congress shall determine, in accordance with constitutional processes, an appropriate response by the United States.

So, if the choice is between an "obligation" and a "policy," what is all the fuss about?

As a matter of diplomacy, there is a huge difference between reserving the right to use force and obligating ourselves, a priori, to come to the defense of Taiwan. The president should not cede to Taiwan, much less to China, the ability automatically to draw us into a war across the Taiwan Strait. Moreover, to make good on the president's pledge, we would almost certainly want to use our bases on Okinawa, Japan.

But there is no evidence the president has consulted with Japan about an explicit and significant expansion of the terms of reference for the U.S.-Japan Security Alliance. Although the alliance provides for joint operations in the areas surrounding Japan, the inclusion of Taiwan within that scope is an issue of the greatest sensitivity in Tokyo. Successive Japanese governments have avoided being pinned down on the issue, for fear of fracturing the alliance.

As a matter of law, obligations and policies are also worlds apart. The president has broad policymaking authority in the realm of foreign policy, but his powers as commander in chief are not absolute. Under the Constitution, as well as the provisions of the Taiwan Relations Act, the commitment of U.S. forces to the defense of Taiwan is a matter the president should bring to the American people and Congress.

I was quick to praise the president's deft handling of the dispute with China over the fate of the downed U.S. surveillance aircraft.

But in this case, his inattention to detail has damaged U.S. credibility with our allies and sown confusion throughout the Pacific Rim.

Words matter.

The writer, a U.S. senator from Delaware, is the senior Democrat on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.

Joseph R. Biden Jr for the Washington Post, May 2001

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

JOE BIDEN WORKED TO UNDERMINE THE AFFORDABLE CARE ACT’S COVERAGE OF CONTRACEPTION

In ’94 Biden boasted to have voted against federal funding for abortion “on no fewer than 50 occasions;” among those was a vote in 1977 against allowing Medicaid to pay for abortions for victims of rape and incest. When that bill succeeded anyway, Biden voted to remove the exceptions again in a separate bill, passed in 1981, that NBC calls “the most far-reaching ban on federal funds ever enacted by Congress.” That same year, Biden supported the constitutional amendment empowering states to overturn Roe. Two years later, in 1983, Biden opposed allowing insurers to cover all abortions for federal employees, except if the mother’s life was at-risk.

For decades, Mr. Biden supported the Hyde Amendment, which prohibits federal funding for abortion under programs like Medicaid. As recently as June 5th 2019, he said he still did.

As vice president, Joe Biden repeatedly sought to undermine the Affordable Care Act’s contraception mandate, working in alliance with the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops to push for a broad exemption that would have left millions of women without coverage.

With an anti-abortion president, Ronald Reagan, in power and Republicans controlling the Senate for the first time in decades, social conservatives pushed for a constitutional amendment to allow individual states to overturn Roe v. Wade, the Supreme Court ruling that had made abortion legal nationwide several years earlier.

The amendment — which the National Abortion Rights Action League called “the most devastating attack yet on abortion rights” — cleared a key hurdle in the Senate Judiciary Committee in March 1982. Support came not only from Republicans but from a 39-year-old, second-term Democrat: Joseph R. Biden Jr.

— Joe Biden argued that mandating contraception coverage through Obamacare would alienate swing-state Catholic male voters

#politics#joe biden#hyde amendment#affordable care act#abortion#contraception#roe v wade#reproductive rights#reproductive justice#aca#healthcare#womens health#womens rights#war on women

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

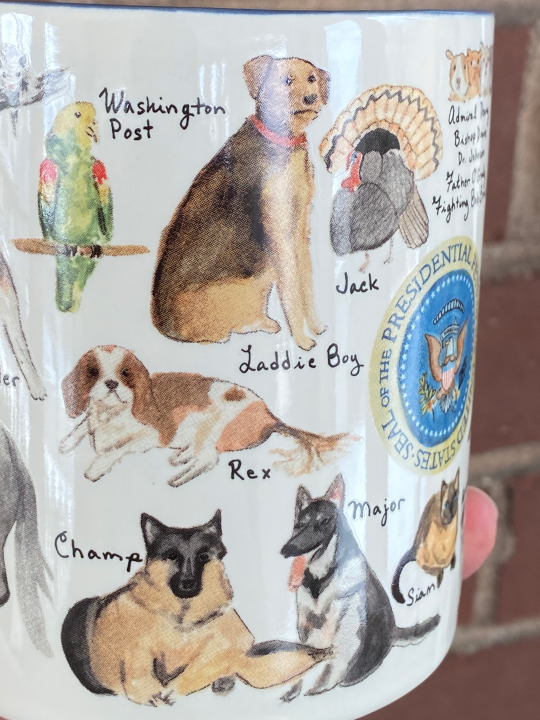

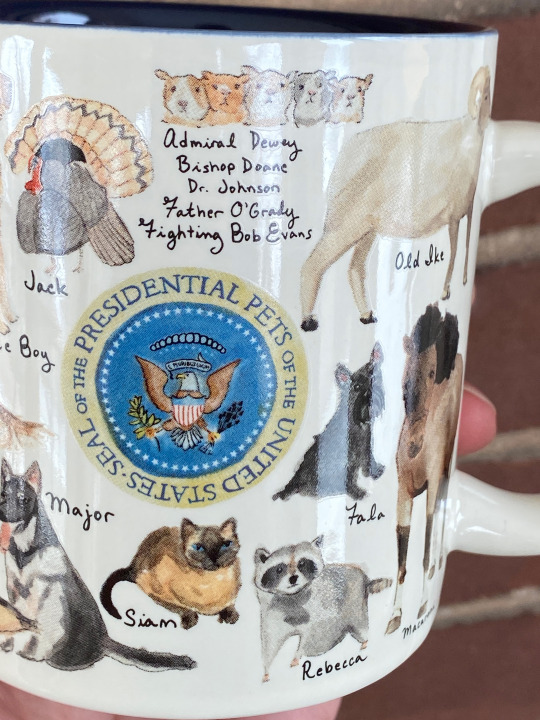

Mugshot Monday - "Presidential Pets" coffee mug by The Unemployed Philosophers Guild with Morning Glory Signature Blend by Peace Coffee

Happy Presidents' Day to those who celebrate!

I have the day off so I'm lounging this afternoon drinking coffee in my Presidential Pets coffee mug.

It's a curated list of presidential pets who lived in the White House for 4 or 8 years depending if their owner survived re-election, or not.

When I think of presidential pets, the first one that comes to mind is "Socks", Bill and Hillary Clinton's cat. The second pet I think of is "Bo", Barack and Michelle Obama's rad dog.

I really don't know my presidential pets and I found some of the pets on the mug very interesting:

Calvin Coolidge had a racoon named Rebecca.

Thomas Jefferson had a mockingbird named Dick.

Theodore Roosevelt had guinea pigs named Admiral Dewey, Dr. Johnson, Bishop Doane, Fighting Bob Evans, and Father O'Grady.

My favorite--JFK had a pony named Macaroni!

Jimmy Carter gets the best name for a Siamese cat: Misty Malarkey Ying Yang.

Only Donald Trump, James K. Polk, and Andrew Johnson did not have a single presidential pet while they were in office. Very vary suspect, don't you think?

Here is every pet on my Presidential Pets coffee mug:

Admiral Dewey, Bishop Doane, Dr. Johnson, Father O'Grady, and Fighting Bob Evans (Theodore Roosevelt)

Barney (George W. Bush)

Bo (Barack Obama)

Dick (Thomas Jefferson)

Emily Spinach (Theodore Roosevelt)

Fala (Franklin D. Roosevelt)

Him and Her (Lyndon B. Johnson)

Jack (Abraham Lincoln)

Laddie Boy (Warren G. Harding)

Macaroni (JFK)

Major and Champ (Joseph R. Biden, Jr.)

Millie (George H. W. Bush)

Misty Malarkey Ying Yang (James Carter)

Mr. Reciprocity and Mr. Protection (Benjamin Harrison)

Old Ike (Woodrow Wilson)

Old Whitey (Zachary Taylor)

Pauline Wayne (William Howard Taft)

Polly (James Madison)

Rebecca (Calvin Coolidge)

Rex (Ronald Reagan)

Siam (Rutherford B. Hayes)

Socks (William J. Clinton)

Sweettips (George Washington)

Washington Post (William McKinley)

The mug impressively displays these 24 presidential pet illustrations and serves as a great introduction to the subject. If you'd like a more comprehensive list, check out the Presidential Pet Museum website.

Cheers to all the presidential pets! 🐕 🐈 🐎 ☕️

See also my 720+ photos from the Mugshot Monday project here: www.MugshotMonday.com– Every Mug Has A Story

2 notes

·

View notes