#ReflectionsontheCaribbean

Photo

In anticipation of the (now virtual) New York Caribbean Week and the annual Labor Day Parade, this August we're highlighting artworks in the Museum's collection that celebrate the presence of Caribbean culture and its diasporas.

New York’s annual Labor Day Parade, also known as the West Indian Day Parade, originated in Harlem with Trinidadian Jessie Waddell, in the 1930’s. In homage to Trinidad’s annual Carnival, Waddell hosted costume parties amongst friends in landmark enclaves, like the Savoy and Audubon Ballrooms, which progressed into a street parade in Harlem in 1947. In 1969, the parade relocated to Brooklyn, under the direction of the late Carlos Lezama (aka “The Father of Brooklyn Carnival”) where it has resided ever since. Participation in the parade is both a rite of passage and an extension of lineage, as a span of all generations flock to indulge in the conducted chaos, as seen in Catherine Green’s images. Green captures the essence of tradition and the nuance of evolution as themes of cultural pride and extravagance meet ancestral reverence and sacredness.

Posted by Jenée-Daria Strand

Catherine Green (American, born 1952). Untitled (West Indian Day Parade), 1991. Chromogenic photographs. Brooklyn Museum, Gift of the artist, 1991.58.1-3; Helen Babbott Sanders Fund, 1991.69.1-2. © artist or artist's estate (Photos: Brooklyn Museum)

#ReflectionsontheCaribbean#caribbean#catherine green#west indian day parade#labor day parade#carnival#brooklyn#nyc#trinidad#harlem#jessie waddell#landmark#savoy#audubon ballroom#parade#carlos lezama#rite of passage#chaos#tradition#evolution#culture#cultural pride#extravagance#ancestral#reverence#sacredness#Brooklyn Museum

618 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In anticipation of the (now virtual) New York Caribbean Week and the annual Labor Day Parade, this August we’re highlighting artworks in the Museum’s collection that celebrate the presence of Caribbean culture and its diasporas.

Where is history housed? In toy sabers, baby dolls, silhouettes of Queens, or in a diamond? Koh-i-noor is one of three portraits by Hew Locke of Queen Elizabeth II that repurposes an iconic image of the British crown through an assemblage of mass produced plastic objects. Locke, who was born in Edinburgh and raised in newly independent Guyana, explores themes of diaspora, globalization, and the complexities of national identity.The title of this artwork refers to the Koh-i-noor (Mountain of Light) diamond which passed through empires and dynasties of Sikh, Mughal and Persia as a symbol of power and conquest. The Koh-i-noor entered the British Crown Jewel collection in 1877 in the wake of the British government’s proclamation of Queen Victoria as the Empress of India. Weaving together the material excess of the global economy and its colonial roots, Locke creates a material geography and archive of something lost. However, the dismemberment and assemblage of the iconic image through fragments also paints a site of possibility. Koh-i-noor invites us to reimagine new landscapes of memory that speak back to and move beyond geographies of domination.

Posted by Akane Okoshi

Hew Locke (Scottish, born 1959). Koh-i-noor, 2005. Mixed media. Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Charles Diamond and bequest of Richard J. Kempe, by exchange, 2007.54. © artist or artist's estate (Photo: Photograph courtesy of the artist and Hales Gallery)

#ReflectionsontheCaribbean#caribbean#art#artist#hew locke#koh-i-noor#queen elizabeth ii#assemblage#sculpture#mass produced#objects#edinburgh#guyana#diaspora#globalization#national identity#india#colonial#colonialism#memory#brooklyn museum#bkmcontemporary#contemporary art

161 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In anticipation of the (now virtual) New York Caribbean Week and the annual Labor Day Parade, this August we’re highlighting artworks in the Museum’s collection that celebrate the presence of Caribbean culture and its diasporas.

On first seeing the work of Jean-Michel Basquiat in 1981, artist Lorraine O’Grady wrote, “I knew what I was looking at; and what I didn't know, I sensed. I never had to translate Jean-Michel, perhaps because I too came from a Caribbean-American family of a certain class.” What does it mean to sense connection with an artwork? For O’Grady, Basquiat’s work resonated because he was speaking from a shared heritage, what she described as "kids no longer Caribbean and not yet American." O’Grady also witnessed how Basquiat was framed in a Eurocentric context as he rose to fame in a predominantly white art world. Reframing the artist’s work through his Caribbean and Afro-descendent heritage, and roots in Puerto Rico and Haiti, reveals how Basquiat was also making art in dialogue with Yoruba religion, Mandé culture, the history of slavery in the Americas, and postcolonial perspectives.

Posted by Forrest Pelsue

Brooklyn Museum, Installation views, Basquiat, March 11, 2005 through June 5, 2005. (Photo: Brooklyn Museum)

#reflectionsonthecaribbean#basquiat#jean-michel basquiat#caribbean#caribbean-american#haitian#puerto-rican#cultural identity#art#artist#brooklyn#nyc#brooklyn museum#french#spanish#english#art history#diaspora#graffiti#african-american#folk art#Mandé#Yoruba#slavery#americas#postcolonialism

124 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In anticipation of the (now virtual) New York Caribbean Week and the annual Labor Day Parade, this August we’re highlighting artworks in the Museum’s collection that celebrate the presence of Caribbean culture and its diasporas.

In his series Pure Plantainum, Miguel Luciano uses the plantain, a cultural symbol of the Caribbean, to explore the colonial dialogue between Puerto Rico and the United States. By coating an actual plantain in platinum, Luciano creates a contradictory object — mirroring the associations of the plantain itself — that is outwardly precious yet inwardly decomposing. The plantain has long had a complex symbolism in the Caribbean, tracing back to plantations, where sap stains on clothing easily identified plantation workers and became associated with race and class. The saying “la mancha del plátano” (the stain of the plantain) was used to speak of those with darker skin, as if blackness, Luciano says, was equated “to a stain upon skin or culture.” Plátano Pride confronts these anti-Black and colorist connotations while acknowledging contemporary changes in culture and identity, especially among Latinx youth in the United States, who have instead embraced the fruit as a symbol of cultural heritage and Afro-Latinx and Latinx pride.

Posted by Gina Vasquez

Miguel Luciano (American, born Puerto Rico 1972). Platano Pride, 2006. Chromogenic photograph. Brooklyn Museum, Gift of the artist, 2008.15. © artist or artist's estate (Photo: Image courtesy of the artist)

#reflectionsonthecaribbean#miguel luciano#plantain#plantano#Plátano#puerto rico#puerto rican#art#artist#photography#photographer#latinx#pride#heritage#fruit#culture#caribbean

112 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In anticipation of the (now virtual) New York Caribbean Week and the annual Labor Day Parade, this August we're highlighting artworks in the Museum's collection that celebrate the presence of Caribbean culture and its diasporas.

Born in Cuba to Jamaican parents, Art Smith grew up in the neighborhoods of Downtown Brooklyn and Bedford-Stuyvesant. In this portrait, Smith wears his Linked Oval Necklace, displaying his trademark use of open lines, negative space, and material elegance. On the wall behind him we see a picture of four-year-old Arthur and his baby brother, Marcus, who died of scarlet fever just a month after their picture was taken. Smith had a strong connection to his family and heritage. His older sister Ina taught him Spanish and, along with his mother Mary, helped buy his first art supplies. Both women were supportive of his artistic ambitions, opening the way for him to become the prominent modern artist he is recognized as today.

Posted by Forrest Pelsue

Arthur Mones (American, 1919-1998). Art Smith, 1979. Gelatin silver photograph. Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Wayne and Stephanie Mones at the request of their father, Arthur Mones, 2000.89.36. © artist or artist's estate ⇨ Art Smith (American, born Cuba, 1917-1982). Linked Oval Necklace, designed by 1974. Silver, amethyst quartz. Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Charles L. Russell, 2007.61.1. Creative Commons-BY

#ReflectionsontheCaribbean#art smith#artist#art#designer#jewelry#modern#brooklyn#cuba#jamaican#cuban#family#heritage#caribbean

69 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

In anticipation of the (now virtual) New York Caribbean Week and the annual Labor Day Parade, this August we're highlighting artworks in the Museum's collection that celebrate the presence of Caribbean culture and its diasporas.

Jamaican artist Ebony G. Patterson uses lavish surfaces and verdant motifs to entice viewers to contemplate not only the power of beauty and fashion but also historical and contemporary violence against Black bodies. In the monumental three-channel video installation …three kings weep…, a trio of towering young men shed tears as they sit silently before a backdrop of floral wallpaper and fluttering artificial butterflies. The videos play backwards, and as a result the initially shirtless men appear to be slowly dressing themselves in colorful clothing with mixed patterns and gleaming jewelry that draw on the styles of dancehall culture and carnival costuming. Silence is intermittently interrupted by the voice of a boy reciting “If We Must Die,” a sonnet that Jamaican-born writer Claude McKay published in 1919 after a summer of intense racial terror and resistance across the United States. In the final seconds of the more than eight-minute-long triptych, as the men’s sartorial performance ends, each proudly crowns himself with a bandana, a bucket hat, and a pair of reflective glasses, respectively. As in McKay’s poem, these three kings are ready to fight for their dignity.

Come view this work, along with other videos from the Brooklyn Museum’s collection, starting September 9 in an upcoming outdoor screening series—stay tuned for details!

Posted by Drew Sawyer

Ebony G. Patterson (Jamacian, born 1981). ... three kings weep ... (excerpt), 2018. Three channel digital color video projection with sound, 8 minutes 34 seconds Brooklyn Museum, Gift of the Contemporary Art Committee and purchase gift of Carla Chammas and Judi Roaman, 2019.11. © artist

#sunsetscreenings#ReflectionsontheCaribbean#Ebony G. Patterson#video art#lavish#beauty#fashion#historical#contemporary#violence#black bodies#video installation#butterflies#floral#wallpaper#jewelry#colorful

50 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In anticipation of the (now virtual) New York Caribbean Week and the annual Labor Day Parade, this August we're highlighting artworks in the Museum's collection that celebrate the presence of Caribbean culture and its diasporas.

Nick Cave is among the most prominent and influential contemporary artists working today, and his Soundsuits are simultaneously costumes and sculptures, their title evoking the rattling, swishing, and rhythm of their motion. Richly detailed in an array of materials and textile applications—here, mass-produced metal flowers, black-on-black sequining, and embroidered floral embellishments—Cave has cited Mardi Gras Indian clothing, Dogon masks and dances of Mali, and Trinidadian Carnival pageantry as visual and conceptual inspirations. Cave designed his first Soundsuit in response to the 1992 police beating of Rodney King, suggesting an armor that conceals race, gender, and class, deflecting white supremacist stereotyping and its often deadly results. In drawing on the street-centric traditions of Caribbean carnival to do so, Cave's works emphasize the liberatory potential of public, shared rituals in music, dance, and art.

Posted by Carmen Hermo

Nick Cave (American, born 1959). Soundsuit, 2008. Mixed media, Exhibited ACTUAL dims: 112 x 43 x 35 in. (284.5 x 109.2 x 88.9 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Mary Smith Dorward Fund, 2009.44a-b. © Nick Cave (Photo: Image courtesy of Robilant Voena

#ReflectionsontheCaribbean#bkmcontemporary#Nick Cave#Caribbean#brooklyn#nyc#art#artist#contemporary artist#soundsuit#costume#sculpture#motion#rattling#swishing#rhythm#textile#material#Mardi Gras Indian#Dogon#mask#dance#mali#trinidadian#carnival#pageantry#rodney king#race#gender#class

49 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In anticipation of the (now virtual) New York Caribbean Week and the annual Labor Day Parade, this August we’re highlighting artworks in the Museum’s collection that celebrate the presence of Caribbean culture and its diasporas.

Born in Puerto Rico in 1833, Francisco Manuel Oller y Cestero became the most prominent Caribbean artist on the international stage in the nineteenth century. He was inspired by local greats, like José Campeche, to become a painter. Unlike other Caribbean artists at the time, Oller studied in Madrid and Paris, and, deeply influenced by the French styles of Realism, Naturalism, and Impressionism, he brought these techniques home in his practice and in the multiple art schools he founded in San Juan.

At a time when U.S. and European artists saw the Caribbean landscape as "exotic" through an imperialist lens, Oller depicted his homeland and its people through the eyes of an insider. Painted in 1885, 12 years after the abolition of slavery in the Spanish colonies, Hacienda La Fortuna is a solemn look at how little conditions had improved for formerly enslaved people in Puerto Rico. Though some workers continued on, now with meager pay, plantation owners employed fewer workers—as seen in this sparsely populated industrial landscape—who were worked even harder. Like many Puerto Rican intellectuals, Oller was an abolitionist. Records show that, in addition to plantation scenes, Oller also painted harsh realities of enslaved people earlier in his career. Though these works are now lost, they are remarkable, as censorship in the Spanish Empire reduced anti-slavery imagery, compared to what was seen in the British Empire and the United States.

Posted by Elizabeth Treptow

Francisco Oller (Puerto Rican, 1833-1917). Hacienda La Fortuna, 1885. Oil on canvas. Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Lilla Brown in memory of her husband, John W. Brown, by exchange, 2012.19

#ReflectionsontheCaribbean#Francisco Oller#Puerto Rico#San Juan#art#artist#art history#caribbean#realism#naturalism#impressionism#imperialist#enslaved#lavery#spanish colonies#plantation#landscape

41 notes

·

View notes

Photo

"Visual surprise is natural in the Caribbean," said the poet Derek Walcott in his 1992 Nobel lecture. "It comes with the landscape, and faced with its beauty, the sigh of History dissolves." He wondered if his work, rather than evoking the past, could contain "celebrations of a real presence." This sentiment is embodied in the mission of the West Indian American Day Carnival Association (WIADCA), organizers of the New York Caribbean Week and the annual Labor Day Parade. In anticipation of these (now virtual) events, this August we're highlighting artworks in the Museum's collection that explore the complexity of Caribbean identity and celebrate Caribbean culture and its diasporas.

Catherine Green (American, born 1952). [Untitled] (West Indian Day Parade), 1991. Chromogenic photograph. Brooklyn Museum, Gift of the artist, 1991.58.2. © artist or artist's estate

#ReflectionsontheCaribbean#caribbean#wiadca#j'ouvert#brooklyn#flatbush#carnival week#nyc#diasporas#identity#culture#art#artists#brooklyn museum

48 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In anticipation of the (now virtual) New York Caribbean Week and the annual Labor Day Parade, this August we're highlighting artworks in the Museum's collection that celebrate the presence of Caribbean culture and its diasporas.

Hatian-born contemporary artist, Yolène Legrand (@atelier_legrand), sources her inspiration from her travels to her homeland, France, and the United States. Often captivated by color, landscape, and cultural presentation, Legrand’s images range from the mountainous lush of Haiti to cityscapes of the Manhattan skyline. Tete de Femme depicts precisely what the title entails, “the head of a woman,” achieved through the intaglio print method of linocut. The colors in this work suggest a nod to the colors on the Haitian coat of arms, a symbol of the battle of independence for the republic––led by Toussaint Louverture. Such an achievement of independence became foundational to the Caribbean pride seen around the world today, as Haiti was the world’s first Black-led republic and the first independent Caribbean state.

Posted by Jenée-Daria Strand

Yolène Legrand Legrand (Haitian). Tete de Femme. Color lino-cut on laid paper. Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Vivian D. Hewitt, 2015.14.8.

#reflectionsonthecaribbean#caribbean#Yolène Legrand#Haiti#haitian#art#artist#linocut#landscape#color#portrait#woman#intaglio#print#haitian coat of arms#haitian independence

44 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In anticipation of the (now virtual) New York Caribbean Week and the annual Labor Day Parade, this August we're highlighting artworks in the Museum's collection that celebrate the presence of Caribbean culture and its diasporas.

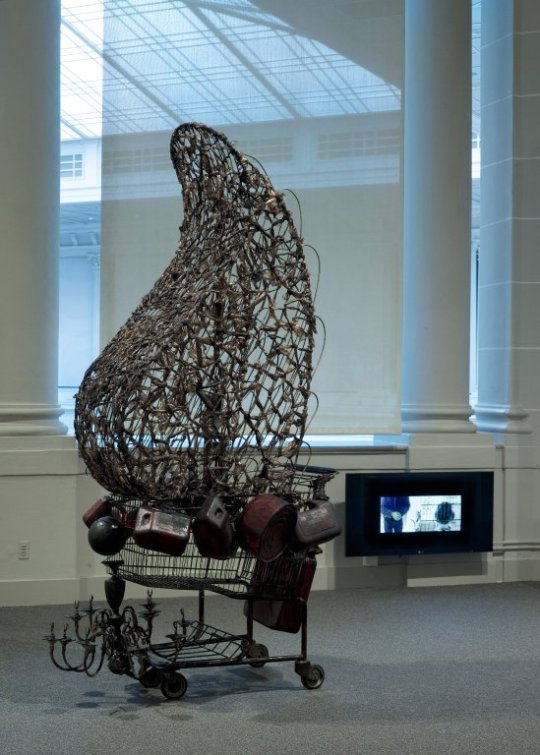

Nari Ward’s layered and evocative sculptural practice takes shape from found, and often discarded, objects. Ward draws on Jamaican folk art traditions of repurposing and reimagining new forms from unexpected materials. In Crusader, a shopping cart acts as a chariot, an old chandelier as its prow, and a ring of used gas cans encircles a tall, curved cocoon made of interlaced plastic bags. The gas cans and applied tar extract point to oil as fuel for energy, and of global conflict and change. The shopping cart references social and material instability at home, given their use by unhoused people for mobile storage. Though Crusader sits silently when installed in a gallery, it was once navigated by the artist, poised within the shopping cart’s protective shell, through the streets of New York City, its subtle rattle competing with the sounds of Harlem.

Starting September 9, come view Nari Ward’s video of Crusader, along with other videos from the Brooklyn Museum’s collection, in an upcoming outdoor screening series—stay tuned for details!

Posted by Carmen Hermo

Nari Ward (Jamaican, born 1963). Crusader, 2005. Plastic bags, metal, shopping cart, trophy elements, tar extract, chandelier, plastic containers. 2008.52.1a-b. © artist or artist's estate Installation view of 21: Selections of Contemporary Art from the Brooklyn Museum, 2008

#ReflectionsontheCaribbean#Nari Ward#sunsetscreenings#brooklyn museum#bkmcontemporary#caribbean#jamaican#sculpture#video art#brooklyn#found object#folk art#shopping cart#chariot#chandelier#social#instability#home#mobile#storage#new york city#harlem

33 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In anticipation of the (now virtual) New York Caribbean Week and the annual Labor Day Parade, this August we're highlighting artworks in the Museum's collection that celebrate the presence of Caribbean culture and its diasporas.

On her visit to the Maroon village of Accompong, Jamaica, Zora Neale Hurston remarked, “Here was the oldest settlement of freedmen in the Western world, no doubt. Men who had thrown off the bands of slavery by their own courage and ingenuity. The courage and daring of the Maroons strike like a purple beam across the history of Jamaica.” Today, August 6th, is Jamaican Independence Day. Inspired by Hurston’s work, New York artist Deana Lawson began to travel regularly to the Caribbean. This photograph, from a local beach in Jamaica, shows the traces of a woman who has just left the frame, her towel still damp. Lawson says, “A constant puzzle for me as a photographer is how to depict the visible and how it connects to the unseen.”

Posted by Forrest Pelsue

Deana Lawson (American, born 1979). Hellshire Beach Towel with Flies, 2013. Pigmented inkjet print. Brooklyn Museum, Gift of the artist and Rhona Hoffman Gallery, Chicago, IL, in honor of Arnold Lehman, 2015.17. © artist or artist's estate

#Deana Lawson#ReflectionsontheCaribbean#Caribbean#new york caribbean week#labor day parade#culture#jamaica#diasporas#brooklyn#new york city#wiadca#jamaican independence day#zora neale hurston#photographer#photograph

29 notes

·

View notes