#Repudiates own confession

Text

The Lost Dragon I - Ensnared.

Summary:

The Greens have repudiated the sucession and ursurped the Iron Throne. After encounting her uncle Aemond at Storms End, he kindaps Vaelys and takes her too Kings Landing - to be used as leverage against her mother.

Whilst the Greens delight in their good fortune, they fail to realise the depths of Aemond's growing feelings for Vaelys and how her presence will ultimately change the outcome of the Dance of Dragons.

Warning(s): Kidnapping, Language, Threats, Angst, Uncle/Niece Incest, Witnessed Consummation, Smut – Fingering, P in V.

AEMOND TARGARYEN x O.C -VAELYS TARGARYEN

MINORS DO NOT INTERACT.

Word Count: 4280

Disclaimer: I do not own any of the House of The Dragon or Fire & Blood characters nor do I claim to own them. I do not own any of the images used.

Comments, likes, and reblogs are very much appreciated.

“You’re lucky you didn’t kill her-how could you be so foolish” snapped Alicent.

"You only lost one eye-how could you be so blind?"

“Her dragon attacked Vhagar-“ reasoned Aemond.

“What does it matter? We have Rhaenyra’s eldest bastard in our clutches, she could prove useful,” said Aegon shrugging.

“Once Rhaenyra discovers that we have her daughter, neither she nor Daemon will rest until Vaelys is returned to them-for all we know they could descend from the skies on their dragons at any moment” urged Alicent picking nervously at her nails.

“I doubt it-None of their dragons are a match for Vhagar“ scoffed Aemond.

“Vhagar may indeed be the largest dragon in the world but even she cannot withstand a combined attack from the dragons they have-you would do well to remember that boy” said Otto sternly.

“What do you suggest?” asked Aemond through gritted teeth.

“We have the girl-we should use her to our advantage. Rhaenyra would not dare attack Kings Landing for fear of her daughters safety” explained Otto.

“Where is my niece currently?” asked Aegon.

“She was taken to the Black Cells Your Grace-“ replied Ser Criston.

“I want her brought here at once-” ordered Aegon, the crown of the conqueror slipping down his forehead.

A small group of guards shuffled out of the throne room and returned a little while later with a thoroughly drenched and bleeding Vaelys Targaryen, her wrists bound together in chains.

"Seven above-have mercy on us" muttered Alicent.

“Welcome back to Kings Landing-“ said Aegon smirking.

“I wish I could it’s nice to be back” replied Vaelys wiping her nose on her tattered sleeve.

The sound of the chains clinking echoed around the throne room.

“My deepest sympathies on the loss of your dragon” said Aegon smugly.

“You can shove your sympathy right up your arse” sneered Vaelys.

“I don’t think your language is very ladylike”.

“Like I care what you think-“ quipped Vaelys.

“I would see you bow before your King” demanded Aegon.

"King? I see no King" snarked Vaelys as she lifted her hand to her forehead and began to look around the throne room.

"I said BOW TO YOUR KING" balled Aegon.

“I bow before no King. All I see is a drunken, usurper CUNT” snarled Vaelys spitting on the floor.

“The bastard dares speak to me in such a manner” roared Aegon.

“I will speak however I please, you will not silence me you drunken wastrel-” quipped Vaelys.

“Mayhaps I should teach the bastard some respect-”.

“-I’m more Targaryen than you will ever be” snapped Vaelys.

“The bastard thinks herself more than a King” said Aegon.

“You look down your nose at me yet you’re nothing more than a half breed. Your dragons blood diluted with that of the Hightower, your nothing but a slithering green snake masquerading as a dragon”.

“Says the strong bastard” raged Aegon.

“I’m not some strong bastard who was lucky enough to favour my mother’s colouring, I am the daughter of the rogue prince himself, Daemon Targaryen” confessed Vaelys.

“WHAT?” exclaimed Alicent.

“Oh please-like you didn’t suspect such a thing” snarked Vaelys.

“How?” asked Alicent.

“On my mother’s wedding night to Ser Laenor-she lay with Daemon” replied Vaelys.

“So, you openly admit that your mother betrayed her marriage to Ser Laenor?” asked Otto.

“Can it be considered betrayal if he gave his permission?” retorted Vaelys.

“He-what?”

“Oh, come on-you know that Laenor only sought the attention of his squires, he couldn’t consummate the marriage, especially when he’d just witnessed the brutal and unnecessary murder of his beloved Joffrey at the hands of your own sworn protector-so of course Daemon was only too happy to volunteer his services” said Vaelys glaring at Ser Criston who narrowed his eyes at her.

“-And your mother was only too happy to accept” snapped Alicent.

“Surely your aware of first night rights-“

“-And what excuse can be conjured for existence of your brothers?” asked Alicent.

“-What do you intend to do with the girl Your Grace?” asked Otto, his patience wearing thin.

“We could always offer her to any of the noble lords who bend the knee and pledge their loyalty to me” mused Aegon, ignoring the look of horror plastered across the faces of his mother and grandsire.

Aemond took a deep breath and folded his arms behind his back, his gaze never leaving his brother.

“We could even leave her chained up in the throne room and they could take turns with her. How many cocks do you think she could she take before she breaks?” said Aegon.

“Your Grace-she is still a Princess of the realm” warned Otto.

“Wed her to me” offered Aemond.

“-And why would I allow such a thing to take place?” asked Aegon.

“I brought her here. She belongs to me-” replied Aemond.

“-And that’s enough of a reason?”

“If not, then mayhaps the prevention of her marriage to Cregan Stark is” said Aemond firmly.

“Stark?” asked Otto.

“Borros Baratheon inquired about her hand in marriage-he seemed interested in taking her to wife, boldly declaring that she would give him many sons, but she refused. It seems her bastard brother has flown to Winterfell and delivered terms in exchange for his support” said Aemond.

“We cannot allow such a match-if Stark honours his father’s oath and bends the knee the rest of the North will follow, we must intervene if we are too secure-“ urged Otto.

“-There isn’t a Stark alive that’s ever broken an oath-you’ve already lost the North and my grandmother was an Arryn, the Eyrie won’t turn against their kin-” said Vaelys smirking.

“-But we still have you” declared Aegon boldly.

“Your Grace-“ questioned Otto.

“-As you were saying brother-you believe that she belongs to you?” mused Aegon.

“There is a debt to be paid and I will take her as payment for the eye her bastard brother carved from my skull”.

“Her maiden head in exchange for your eye? Assuming of course that she is still a maid, after all she is the daughter of a whore” quipped Aegon smirking.

"The only whore I see is YOU" yelled Vaelys.

"Hold your tongue-or I will have it removed" snarled Aegon.

Vaelys was about to answer back, but then she caught Aemond's eye, and he discreetly shook his head.

Deciding it was better to keep quiet, Vaelys lowered her gaze to the floor.

“I will have her as my wife and I will take what is mine” said Aemond, his voice firm and unwavering.

“And when her maidens blood stains your cock. What then?” asked Aegon.

“She will still have her uses” replied Aemond firmly.

“Very well brother. You may take her to wife” said Aegon smirking at the look on Vaelys’ face.

“Your Grace, Aemond has already agreed to marry one of Borros Baratheon’s daughters, he pledged his support to you based on that promise” urged Alicent.

“Offer Daeron’s hand instead. I don’t really think it matters which Prince marries his daughter” replied Aegon shrugging.

“But Your Grace-“ said Alicent.

“-My brother’s debt will be paid” said Aegon firmly.

Just as Alicent was about to respond, her father shook his head and she sighed despondently, Aegon had clearly made his mind up and now her favoured son would be stuck with a bastard for a bride instead of someone more worthy of his station.

“If some of the lords who have declared for Rhaenyra see that her daughter is wed to Aemond, we may be able to sway them to our side” said Otto thoughtfully.

“Exactly-now take your bastard Aemond and see that she is made presentable-you will wed on the morrow, mother will make the arrangements” ordered Aegon.

“Your Grace” muttered Alicent through gritted teeth.

“YOU-“ snapped Vaelys taking a step forward only to be stopped by Aemond.

“Ser Arryk-Escort my betrothed to her temporary chambers, ensure that she is bathed, and that cut is taken care of” said Aemond sternly.

“Yes, my Prince” replied Ser Arryk.

“You may also want to have the chains removed as well?” suggested Otto.

“Hmm” rasped Aemond.

“Cunt” snapped Vaelys.

“Careful niece-come tomorrow, my brother will have other uses for that mouth of yours” said Aegon smirking.

“Then he will find himself without his cock” replied Vaelys as Ser Arryk lead her out of the throne room.

After she had been thoroughly bathed, Vaelys was sat on a chair under the watchful eye of Ser Arryk waiting for Maester Orwyle to arrive.

“Do you not wish to enquire about the wellbeing of your brother?” asked Vaelys as she watched the maids busying themselves with tidying up.

“I’m sure my brother is fine” muttered Arryk solemnly, his eyes fixed upon the door.

“You know it amazes me how different twins can be. I mean there’s Erryk who is loyal, and then there’s you-“ said Vaelys.

“-My brother is a traitor” said Arryk.

“Your brother swore towards the rightful Queen-he is a man of honour, unlike some I could mention” said Vaelys, a soft knock at the door diverting her attention away from her guard.

“Prince Aemond” said Arryk bowing slightly.

“You can wait outside-“

Ser Arryk nodded his head slightly and then shuffled out of the room, only to come to a standstill just beyond the threshold of the door.

“He is to be your personal guard-he will remain stationed outside, so before you get any ideas, remember he’s there” said Aemond as he waved his hand, and a nervous looking maid placed a stool in front of Vaelys.

“What are you doing?”

“The cut needs stitching, I’ve stitched plenty of my own wounds before, or would you rather have the Maester do it, after all he did such a wonderful job on my eye” said Aemond.

“I thought it was Maester Selkin who stitched your eye?“ asked Vaelys.

“On Driftmark-but I’ve had other procedures since then” replied Aemond.

“Other procedures?”

“Removal of my eyelids” said Aemond as he threaded the needle and raised his hand to Vaelys who flinched away nervously.

“I-I-“ stuttered Vaelys.

“If I was going to hurt you, then I would have done it before I brought you to Kings Landing”.

“But you did hurt me-you killed my dragon” whispered Vaelys softly as she leaned forward an allowed Aemond to begin stitching the cut above her eye.

“I’m sorry about Archonei-” whispered Aemond.

“-Don’t say her name” snapped Vaelys.

“It was not my intent to kill her”.

“You chased after us on that old bitch dragon of yours, what did you think was going to happen?” quipped Vaelys, grimacing as Aemond pulled the thread through her skin.

“Vhagar was defending me after your dragon attacked her”.

“Archonei was frightened, she was much smaller than Vhagar, how would you feel having that thing chasing after you” said Vaelys.

“If you didn’t insult me in the first place then I wouldn’t have chased after you”.

“I heard you-shouting your commands, but she wouldn’t listen. Does your King know that you can’t control your dragon?” asked Vaelys flinching again as the needle pierced her skin.

“It was a momentary lapse in-“

“-Your mouldy rock is obviously getting senile in her old age” retorted Vaelys.

Aemond paused for a moment, debating with himself on whether or not he would engage Vaelys in the argument she was intent on starting, but after a few moments he decided against it.

“We are to marry on the morrow-I suggest you rest well” muttered Aemond as he tied the thread and snipped it.

“If you think that I’d willingly marry you dragon slayer, then your even stupider than you look”.

“The alternative is much worse-“ muttered Aemond raising from the stool.

Vaelys looked at Aemond and took a deep breath, she knew Aegon’s threat of offering her to any Lords who bent the knee was not an empty one and despite her anger towards Aemond for what he had done, he was clearly the lesser of two evils.

She would rather be his wife, than suffer the alternative. Her fathers words echoed in her mind ‘Seize your opportunity and do what you must in order to survive’.

“Fine. I will marry you” snapped Vaelys.

“Get some rest Princess. Tomorrow you will be my wife” replied Aemond as he turned on his heel and left the room.

Aemond was stood beside the high septon. He was elegantly dressed, his black tunic decorated with silver dragons and his Targaryen cloak tied loosely around his shoulders. His long hair tied back in its usual half up, half down style.

The horns signalled the beginning of the ceremony and begrudgingly Vaelys took Aegon’s arm.

“You look beautiful. Green suits you” said Aegon smugly.

“Eat shit-” muttered Vaelys.

“Thank you for escorting the bride Your Grace. If you would be so kind as to wait for the Princess to remove her maiden cloak” said the Septon.

Vaelys undid the ties of her maiden cloak and handed it to Aegon who nodded respectfully to the Septon and took his seat next to Alicent and Helaena.

“You may now cloak the bride and bring her under your protection” said the Septon loudly.

Aemond removed the cloak bearing the colours of house Targaryen and draped it around Vaelys’ shoulders.

Aemond then took Vaelys’ hand and smiled as the Septon tied their hands together by a ribbon.

“In the sight of the seven, I hereby seal these two souls, binding them as one, for eternity. Now you may look upon one another and say these vows together” exclaimed the Septon.

“Father, Smith, Warrior, Mother, Maiden, Crone, Stranger. I am his and he is mine from this day until the end of my days” said Vaelys, her lip wobbling slightly.

“Father, Smith, Warrior, Mother, Maiden, Crone, Stranger. I am hers and she is mine from this day until the end of my days” declared Aemond loudly.

“The vows have been spoken. You may kiss your bride”.

Aemond hesitated for a moment before he leaned forward and pressed a gentle kiss to Vaelys’ lips.

“ñuhon” whispered Aemond as he pulled away (Mine).

The celebration after their wedding was in full swing, how Alicent had managed to pull this off in the limited time she had, Vaelys didn’t want to know.

King Aegon was sat at the head of the table, with a smiling Alicent and Otto by his side.

Vaelys sat next to Aemond near the head of the table, plastering on a smile as Lords and ladies loyal to Aegon came up to wish them well. Tyland Lannister, and one that seemed to linger, Jasper Wylde.

"Many good wishes too you Prince Aemond and Princess Vaelys. A match many shall pray for a fruitful outcome. I must admit Princess, the tales of your great beauty have not been exaggerated".

Vaelys shifted uncomfortably in her seat and Aemond scowled.

"Thank you," nodded Vaelys politely.

All through the feast and dancing, Vaelys couldn’t help but think about her mother.

Did her mother know that she was in Kings Landing? Or had the broken pieces of Archonei been discovered and it was assumed that she had died alongside her dragon?

Her mother was still recovering from the pain and loss of her last pregnancy when she had agreed to let Vaelys fly to Storms End, how cruel would it be to let a mother already grieving for the loss of one daughter, believe her other was also dead.

“Valzȳrys” muttered Vaelys (Husband).

“Is everything ok?” asked Aemond.

“Issa muñā, does she know that I’m here?” (My mother).

“I don’t know-I’ll asked my grandsire” replied Aemond as he rose from his seat and made his way towards his grandsire who was in conversation with Larys Strong.

“Does Rhaenyra know that her daughter is here?” asked Aemond.

“The Princess has not yet been informed of-“ said Otto.

“-She’ll know when she receives the sheets stained with her daughter’s maiden’s blood” interrupted Aegon.

“Perhaps a letter would be sufficient-” mused Aemond.

“No-our whore sister will be sent proof that her daughter has been wedded and bedded. Speaking of which I must inform you brother that the consummation will need to be witnessed, given our older sisters past behaviours”.

“Your Grace-“ exclaimed Aemond.

“We cannot have Rhaenyra contesting the marriage-“ urged Larys.

“Lord Strong is right-“ said Otto.

As much as he could try an argue against it, Aemond knew couldn’t. Rhaenyra would indeed challenge the validity of her daughters marriage, and the witnesses were a preventative measure.

“I request the minimum number of witnesses and sheer curtains-“

“Arrangements will be made,” said Otto.

“Your no fun” muttered Aegon tipping a large gulp of wine.

“I do not wish for my wife to be displayed in such a manner” snapped Aemond.

“Careful brother-anyone would think that you care for the bastard” snarked Aegon.

“She is my wife-“ said Aemond.

“-And that little crush of yours has nothing to do with it?”

“I don’t know what your talking about” snarled Aemond.

“I saw that cuntstruck look on your face when our sister brought her brood of bastards to the Red Keep defending Jace’s claim to Driftmark-Couldn’t keep your eye off our niece, although I must say I don’t blame you. She has grown rather beautiful. Perhaps I’ll take a leaf out of our uncles book and insist on first night rights” said Aegon.

“You have no right” replied Aemond, his heart pounding in his chest.

“I am the King-I have every right, but what sort of brother would I be if I deprived you of the chance to deflower a maid-it’s not as if the last woman you bedded was one” laughed Aegon.

“Don’t ever mention that again” ordered Aemond as he turned on his heel and returned to Vaelys who was now huddled with Helaena.

“I couldn’t talk him out of it-” said Aemond.

“At least you tried” muttered Vaelys, her shoulders slumping.

“Come good sister-I shall escort you to your new chambers” whispered Helaena.

“I’ll distract Aegon and the others” muttered Aemond.

“I know it might not make sense, but it was necessary for Aemond to bring you here”.

“I’m sure it was-“ muttered Vaelys as she watched Aemond bump into his brother, causing the cup of wine he was holding to spill all over the floor.

“You will see in time, and don’t worry you will fly again,” said Helaena.

“I will?” asked Vaelys as she followed Helaena out of the throne room.

“A dragon across the sea, a bronze heart waiting to be free,” said Helaena.

“What?” exclaimed Vaelys.

“A dragon across the sea, a bronze heart waiting to be free,” repeated Helaena as she came to a stop in the middle of the corridor.

“These are not my chambers” mused Vaelys.

“No-there Aemonds. You are to share, it’s important” muttered Helaena as she pushed open the door, took Vaelys by the hand and pulled her inside.

“I’m scared” whimpered Vaelys.

“Aemond will take care of you-he’s not the monster you think he is,” said Helaena.

“He brought me here”.

“I was necessary-a dragon across the sea, a bronze heart waiting to be free. The dragons begin to dance, blood will be shed, begins when two are wed,” said Helaena.

“You keep saying that but-“ uttered Vaelys as the door swung open and Aemond walked in, closely followed by Aegon, Otto, Larys Strong, Tyland Lannister and Maester Orwyle.

“It’s time-“ declared Aegon brightly.

“Will you stay?” asked Vaelys.

“Yes” replied Helaena softly as she stood next to Aegon who huffed impatiently at Aemond who was stood silently observing Vaelys.

“Would you help me with the gown, husband?” asked Vaelys as she turned from him and swept her hair away from her back to reveal a great number of fiddly buttons and laces.

“Of course,” replied Aemond as he reached forward and began undoing his wife’s wedding gown.

Soon she was stood in nothing but a thin shift and Aemond felt his heart quicken in his chest at the sight of her nipples through the sheer fabric.

He was no maid, Aegon had seen to that when he’d dragged him to the street of silk on his thirteenth name day. But Vaelys was no paid whore, that would whisper sweet lies into his ear and make him feel dirty.

She was his wife, and he would treat her as such.

Aemond began pulling off his own clothes as Vaelys climbed into the bed. Her cheeks tinged pink as she glanced nervously at the witnesses who were silent.

“Focus on me. Not them” said Aemond as he finished undressing himself and climbed into the bed.

Vaelys nodded nervously as Otto moved forward and closed the sheer curtains, they didn’t provide much privacy, but it was better than nothing.

“I-I’m ready husband” whispered Vaelys as she pulled off her shift and discarded it on the floor.

Vaelys laid down and smiled shyly as Aemond gazed at her naked body.

“Gevie” whispered Aemond as he slowly reached out and ran his fingers over Vaelys’ breasts (Beautiful).

Goosebumps erupted over Vaelys’ skin as Aemonds hand began to move lower.

“I-I need to prepare you” whispered Aemond.

“P-prepare me?” whispered Vaelys.

“I don’t want to hurt you” replied Aemond.

Vaelys gasped when she felt Aemond’s fingers rubbing her folds.

“Aemond” exclaimed Vaelys as her husband slipped a finger inside her.

Aemond buried his face in his wife’s neck as he began peppering kisses along her smooth skin as he added another finger to prepare her as best, he could.

But in the back of his mind, he was still aware of the witnesses standing at the foot of the bed.

“Come on. Get on with it” groused Aegon.

Aemond removed his fingers and then laid between his wife’s open legs, supporting his weight on his left arm as he reached down and took his hard cock in his hand and placed the tip of it against his wife’s slick entrance.

Vaelys shut her eyes tight and took a deep breath as Aemond sheathed himself within her.

“Listen to her whimpering, who would have thought a whore’s daughter would be so cock shy” laughed Aegon.

“Don’t listen to them-I won’t let them see you” muttered Aemond softly.

Vaelys couldn’t stifle the whimper of pain as she felt Aemond’s cock press further into her.

“That’s it Aemond fuck her harder” exclaimed Aegon gleefully.

“Your doing so well-” muttered Aemond trying to control himself.

Vaelys’ cunny choked his cock so tight that he needed a few seconds to adjust, making him terribly aware that he was not going to last for too long.

Aemond’s cock twitched and throbbed with need, and he released a shuddered breath while Vaelys sighed in relief.

“The pain will ease,” rasped Aemond, waiting for his wife to adjust.

After a few moments, Vaelys nodded slowly her hands grasping the white sheets tightly as Aemond pulled back and thrust forward again.

Aemond rested his head in the crook of Vaelys’ neck as he thrusts faster, his quiet moans muffled against her skin.

“Your perfect-“ whispered Aemond.

Feeling a spark of pleasure Vaelys let go of the sheets and slowly placed her hands on Aemond’s back, holding him close as his movements become more erratic.

Aemond pushed into the hilt for one last time and groaned loudly as his cock throbbed and he spilled his seed.

“A-Are you ok?” Aemond as he gently pulled his softened cock from his wife.

Vaelys nodded, her fingers digging into the fabric of the bed.

Aemond pulled the bedcovers over Vaelys and then moved to sit on the edge of the bed, his eye drawn to the red ring of Vaera’s maidens blood that now stained his cock.

“Are you well Princess. Do you need me to examine you?” asked Maester Orwyle.

“No, I’m-“ muttered Vaelys.

“-The marriage has been consummated. Get out” snapped Aemond.

“The sheets brother” said Aegon.

Aemond slowly ran a hand over his face before he jumped off the bed, his eye moving to Vaelys who clutched the bedcovers too her chest and slowly lifted her body from the bed allowing him to pull the sheet from under her.

“There-“ snarled Aemond as he threw the sheet towards Aegon.

“I see she was a maid after all” quipped Aegon as he examined the blood stained sheet.

“This will do nicely, I’ll make sure to send it to our sister on the morrow, confirming that her precious heir has been wedded and bedded” Aegon as he quickly rolled up the bloodstained sheet.

“You’ve got what you wanted now get out” retorted Aemond.

There was a brief shuffling off feet, before the door to their chambers opened and closed, leaving the two of them alone.

“Are you ok?” asked Aemond as he climbed back into the bed.

“I’m fine” whispered Vaelys.

“We should get some sleep-it’s been a long day” said Aemond as he laid down,

“W-Will you hold me. Please?” asked Vaelys her voice small and barely audible, the tears running down her face.

Aemond slowly nodded and reached towards Vaelys pulling her trembling body against his.

It took far longer than Aemond would have liked for his wife’s trembling to cease, but eventually she fell asleep with her face pressed against his chest.

After discarding his eyepatch on the nightstand, Aemond gazed at Vaelys for seemed like hours.

He could still see the faint tracks of dried tears on her face, and with a shaking hand he reached out and gently stroked her cheek.

“I’m sorry” whispered Aemond as he pulled her closer and closed his eye.

#house of the dragon#aemond targaryen#hotd aemond#aemond fanfiction#hotd fanfic#aemond fic#aemond x oc#aemond x original female character#hotd fic#aemond one eye#aemond#aemond smut#prince aemond#prince aemond targaryen#aemond targaryen smut#hotd#hotd smut#aegon ii targaryen#otto hightower#alicent hightower#helaena targaryen#larys strong

181 notes

·

View notes

Text

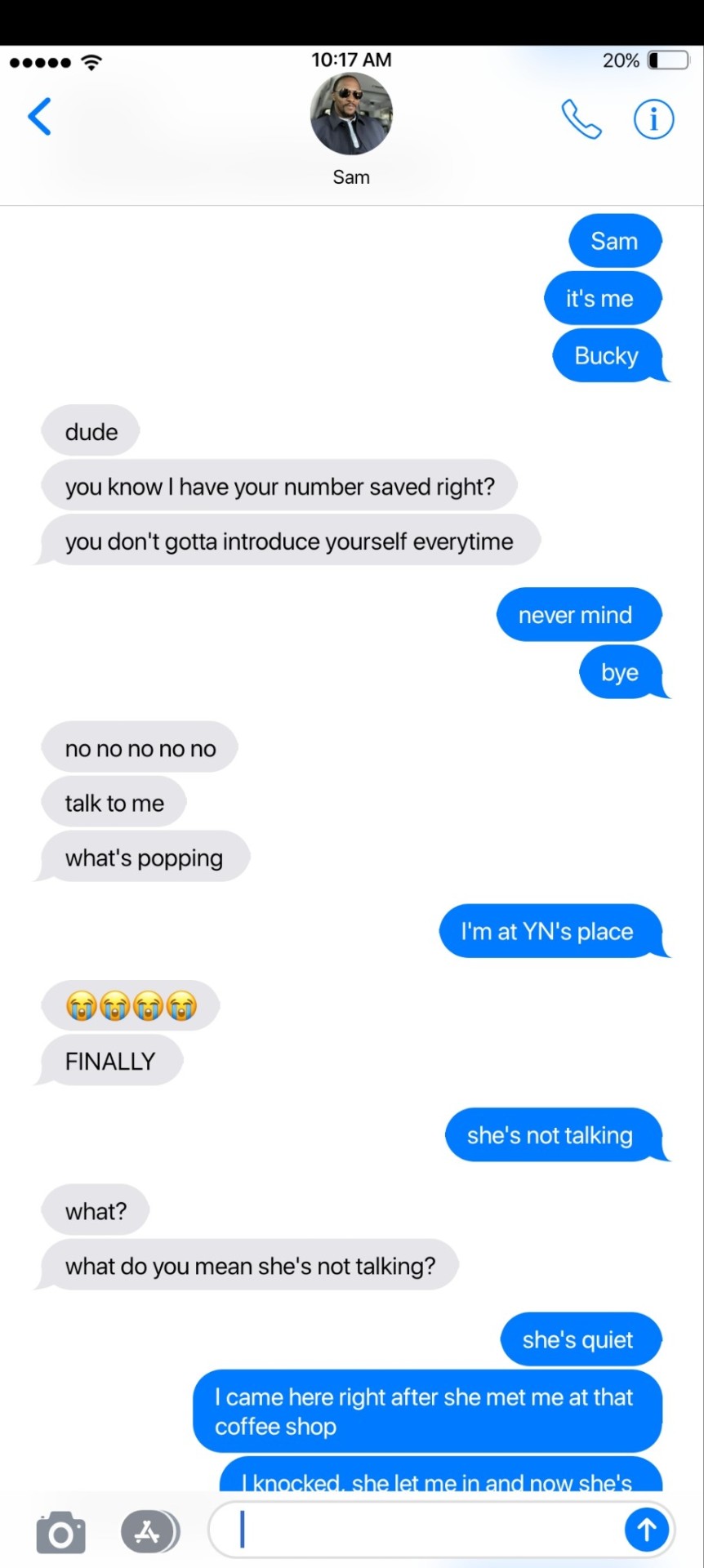

[Bucky Barnes] set of 2 - part 12

AN: hello there! i shoul've post this on christmas but life got in the way ;) anyway, hope you like it

“I know a lot of your quiets.

"Quiets?"

"Yeah. Usually, I can tell some of them. I know when you’re alone with me and you’re quiet, it’s because your chilling, just like I do when I'm with you. Your quiet when I did something stupid, and you don't agree, but don't wanna bug me about it. Your quiet when you're tired from work or when you're pissed about something and don't want to talk about it. But I don’t know this one. What’s this one?”

You looked at him, amazed by how he could differentiate your silences. You were always a big talker, always letting everyone know your thoughts and considerations, and you were like that with him too, but with Bucky, you learned to shut the hell up a little bit and listen. In the beginning, he didn't say much, at all. With more time, he began to share a little about himself and express some interest in your life: asking how your day was, if your kitchen knives were sharp, and if you wanted him to sharpen them for you. He asked about how your door made that squeaking noise when you opened it up and if you wanted him to fix it for you. He told you about Sam's ridiculous jokes or about how annoying he was. He even told you one day about one of his nightmares: you, him and Sam were in your living room watching some movie and the three of you fell asleep. Bucky woke up from his short sleep, and you and Sam were dead, and his hand was bloodied. He had killed you and Sam, and there was nothing he could do. There was no way to bring you back.

He talked to you about Steve and how much he missed his best friend. About how much he hated this age, and one day he confessed about his consideration of ending his own life once. He wasn't supposed to be alive by now. This was not his time. His time has passed. But he had things to do. Ties for mending. Peace to be made. People who needed closure. Living a miserable life would have to do. Until he met you.

With your quick words and quicker reactions, Bucky liked how you seemed to not repudiate him right away. Not even when you recognized who he was or what he had done. Yes, he checked his entire background to see what kind of person wouldn't be surprised by a killer like him, but nothing came up. You had a clean record. Average grades in elementary and high school, no college, ordinary jobs with even more ordinary pay, and a history of boyfriends that bordered on pathetic because they were so boring. SHIELD really knew things, my goodness.

After making sure you weren't a monster like him, Bucky became even more intrigued. You seemed to like having him around. At first, he expected you to ask about all the Avengers, about the building where he stayed, and about the horrors he had seen. And also done. But you didn't ask any of that. Instead, you asked a million questions about what he didn't yet know about this new world: the new music he missed, the incredible films in color and 4K, cinema, food that was now being delivered… it was a new world, and he didn't seem to know anything about it. Nothing about the positive sides.

You talked too much, and he loved it. Bucky became even more intrigued when he began to notice how you began to mold yourself into his style. How you started to enjoy the silences like he did too. The chances of Bucky becoming a talker were almost zero, but if he could do it for anyone, it would be you. You brought hope that this terrible, cold, clueless, cruel and miserable world could still be good. That it could still be patched up. The world was good because you were in it. And it's good that he's alive to live in this era.

"Doll? What is this one?", he asked, bringing you back from your thoughts, his piercing blue eyes on you.

"This is me being upset, Buck", you confessed. "I'm so happy that you're in front of me right now, but I'm still upset with you. For always giving up on me first. For always making decisions and giving the excuse that it is in my best interests. You don't seem to know me. You know my silences, and you know so much about me, but you have no idea what I value most. I told you that I am aware that I am ridiculously ordinary, and when you act like this, when you push me away, I feel like I am being nullified. As if my opinion didn't matter. You know me, but you can't read my thoughts, so I'll clarify them for you: I love you.", You stared at him. "I love you, and it's more than just like a friend, and I feel so cringe right now that I could die, but you can't seem to get the hint, so I'll be clear as day about that. It took me a while to understand exactly what I was feeling, but I finally understood. I felt like an idiot for going after you when you have this terrible tendency to avoid me. I kept asking myself, "Why the hell am I doing this? Why can't I let this idiot go? Why can't I be content with being your friend in a distant way? Why am I thinking about his eyes on me? Why does he look at me like that? Like he loved me? I thought a lot, Buck. And I can't let you go. And I'm not going to be a hypocrite and say that you don't need to love me back. You may not admit it out loud, but I know you love me. You act like you love me. You look at me like you love me, and you take care of me like you love me. See? I can't shut the fuck up, but you love me anyway. I can see."

Bucky grinned. Huge. And he looked at you with his blue eyes from head to toe, as if he were memorizing every detail of you in his mind, the smile never leaving his face. A happy, childish smile that made you feel like his heart was going to explode out of his chest.

"I never understood the concept of the expression falling in love before, but I did it with you. When I first saw you, I felt like I had stomped on my own feet and fallen on my face without any protection. I felt like my teeth were knocked out, and my face got all scratched.", the soldier could see the clear confusion splattered on your face. "I wasn't prepared for you to walk into my life, doll. I felt deficient, surprised, and confused, and I didn't think love could make someone feel like this. If I'm being honest, I still don't feel prepared at all. I'm afraid to you in my hands and end up breaking you.", he confessed. "You know my past and what I did, and I should be far away from you, but I can't. I just can't. It's painful when my mind tries to convince me I don't deserve you, but I love you with my life. I love you like I've never loved anyone else."

"Good, because you're getting rid of me that easy. And you can fall as much as you want.", you smirked at him.

“You’ll catch me, right?”, Bucky asked.

“Always. Merry Christmas, idiot.”

"Merry Christmas, Doll."

Tag list: @almosttoopizza @creat0r-cat @aesthetic0cherryblossom @cjand10 @sapphirebarnes @nouk1998 @unaxv @rain-lavender-rain @winterslove1917 @marvel-wifey-86 @literaryavenger @kandis-mom

#bucky barnes x female reader#bucky barnes x reader#bucky barnes x oc#bucky barnes x y/n#bucky barnes fluff#bucky barnes x you#bucky barnes#bucky fic recs#bucky fic#fluff bucky#bucky texts#bucky x female reader#bucky x y/n#bucky fics#bucky x you#bucky x reader

39 notes

·

View notes

Note

can i get 28 and natsume? thanks >_<

〈gn!reader x sakasaki natsume ❇〉

a/n: listened to temptation magic on repeat while writing this hehe thanks for requesting, i hope you enjoy!

kiss meme !!

28. One person tracing the other’s lips with a fingertip until they can’t resist any longer, tilting their chin towards them for a kiss.

What if the protagonist’s fairy godfather wanted them to see him as their destiny rather than some faraway prince who falls in love without knowing the protagonist’s heart and soul? Rapt with adoration, the godfather watches over them while granting their vibrant wishes in hopes to see a smile blossom on their face.

All while knowing that this fairytale had no happy ending for him.

“Ah, Kitten♪ What a coincidenCE” Natsume’s velvety greeting stirred you into gazing up from the notes you were reviewing one last time. “Where are you headED?”

“Hello, Natsume-kun! I need to submit this report to Tenshouin-senpai. Tsukinaga-senpai completely forgot to complete it, so I helped him out and I’m on my way now,” you elucidated, “Is it alright if I stop by your little hiding room later? I have something I’d like to ask you.”

Interest carved itself on his face as he raised a brow, curiously asking, “Are you finally asking me OUT? My answer has always been yES♪”

You shook your head, staving off the wavelets of embarrassment by clutching your papers up to your face. “N-Nothing like that! Can I count on you to be there?”

There was no chance Natsume would let you down—he was pretty intrigued by what you needed him for, too—and as he watched you bow your head and dash over to the student council room, he wondered if you’d still have that kind of energy for him.

——Copious wisps of purple and green fumes enveloped Natsume’s occupied hidden space by the time you gently rapped against the door for entry. You weren’t unused to inhaling the sorcery Natsume produced, rather you were effortlessly able to address him before striding on over to a chair.

“Welcome, Kitten; if you don’t mind waiting, I’d like to finish this concoction firST. Or you can talk as I woRK,” Natsume, who didn’t glance up from his bottles, said.

You vacillated whether to inquire now or not; there was a favor you only felt you could ask him to do for you, but it was pretty sensitive… Still, you supposed you made it this far, why delay the inevitable? In this case, you could ask him without having his enchanting eyes staring into your own.

“I don’t mind, I’ll go ahead and ask,” you started, gaze transfixed on Natsume’s back—his lapcoat fluttering with his movements, causing a flood of butterflies in your stomach. “Would you be willing to help me apply lip-gloss? On myself, of course.”

Natsume’s shoulders stiffened at your bold, unexpected question. “Do I look like I wear any more make-up than necesSARY? I don’t have any to give yOU,” Natsume gave a staid response, hoping to steady the confusion swirling in his mind.

Why were you suddenly interested in this? You always dressed more plainly, not adding anything more than the basics to your appearance. Even if he believed you were perfect the way you were, Natsume would never repudiate an opportunity for magic; your chance to bestow a glamorous spell onto yourself.

“No, no, I have my own I want to try! I just know I’m going to mess up putting it on by myself, so…”

Your sheepish voice was so cute and enticing, it made Natsume almost unable to concentrate on his work. “I’ll help yOU, Kitten. Don’t worRY.” But he couldn’t disrupt the progress, so he devotedly maneuvered himself into finishing up before his thoughts melted into you and only you.

Lifting a vial up into the air, watching the bewitching essence spiral within, Natsume held a pleased smile. And he took this final chance to ask, “What’s the occasiON? For the lip-glOSS.”

“I want to charm someone’s heart into becoming mine,” you confessed truthfully, yet still keeping it vague. You couldn’t outright tell him who it was, not right now.

That ambiguity was also unforeseen from you, you who was always honest to a fault (how many times have you corrected him on that you two weren’t dating?). “Aren’t you full of surprises todAY, Kitten,” Natsume wondered aloud whilst setting down his vial and removing his protective goggles.

Pulling up a chair in front of you, Natsume settled in as his knees bumped with yours from the propinquity. Having him so close to you now had your heart palpitating, and you hurriedly delved into your bag and fished out the infamous lip-gloss.

“Here, Natsume-kun. Thank you,” you expressed your gratitude softly, handing it over to him.

You immediately had to shut your eyes, incapable of further looking at him due to the swell of heat in your cheeks. You knew it was visible on your face, how apprehensive you were, but there was nothing else you could do at this point.

Natsume examined the bottle, perusing the words ‘sparkling milkyway’ as the contents within. It didn’t say anything about flavor or anything else. Unscrewing the cap, Natsume could already see specks of glitter adorning the fine brush.

Lithe fingers slid under your chin to keep you in place, and Natsume wordlessly began spreading the lip-gloss over your lips. This was probably an effort made for someone else, someone other than him, his insecurities told him.

The thought made his heart ache, and yet Natsume continued to help you—absolutely beguiled with how your trembling lips responded and twitched to his motions. “Ah, shit, I missED” Natsume cursed lowly under his breath.

Without ruminating on it, Natsume impulsively reached forward and used his finger to swipe at the overflow dripping from the corner of your lips. He salvaged what he could, now using his fingertip to trace along the shape of your lips to proportion and clean up the gloss embellishing your insanely adorable lips.

The vivid glitter dotted over the shine of the gloss itself made Natsume’s stomach jump, the sensation looping in on itself as temptation corrupted his pure intentions. Before he knew it, Natsume was shifting his mouth closer to yours.

You were so irresistible—his heart had already belonged to you since he first met you, and this mysterious spell you were casting was affecting him worse than expected.

All of a sudden, Natsume found your hands clasping his cheeks and pulling him into you. Your lips pressed against his, rounding passionately and savoring the diminutive squeak that leapt from his throat out of surprise.

When you disconnected your mouth from his, there was an alluring pop sound resounding in the room. Your deep, flushed breaths mingled together and caged you to each other.

Mischievously sticking your tongue out, noting how your glitter fused with his lips now, you admitted, “Did my magic trick work?”

Natsume’s reddened complexion was telltale of your effect over him, and he leaned his forehead against yours. “No, it didn’t—because I’ve always been YOURS,” he articulated as smoothly as he could, still feeling the fluster twisting his vocal-chords. “You… Hm, maybe I did fall for you harder, thouGH♪”

#c: sakasaki natsume#sakasaki natsume x reader#enstars x reader#ensemble stars x reader#x reader#prns: they/them#gn reader#drabbles#kiss meme#enstars

243 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Andrew Doyle

Published: Dec 12, 2023

Towards the end of Christopher Marlowe’s play Tamburlaine Part Two, our marauding anti-hero burns a copy of the Quran, along with other Islamic books, as a kind of audacious test. “Now, Mahomet,” he cries, “if thou have any power, come down thyself and work a miracle.” Two scenes later, he is dead.

We might see this as a cautionary tale for our times. After all, it isn’t only Turco-Mongol conquerors who find themselves punished for Quran-burning. Last week, the Danish parliament voted to ban the desecration of all religious texts following a spate of protests in which copies of the Qur’an had been destroyed. Inevitably, the new law has been couched as a safety measure. This burning of the book, claims justice minister Peter Hummelgaard, “harms Denmark and Danish interests, and risks harming the security of Danes abroad and here at home”.

He has a point. Even unconfirmed accusations of Quran-burning can be sufficient to prompt extremist violence. In 2015, being accused of defiling the holy book, Farkhunda Malikzada was beaten to death by a ferocious mob in Afghanistan while bystanders, including police officers, did nothing to intervene. Many filmed the brutal murder on their phones and the footage was widely shared on social media. In 2022, a mentally unstable man called Mushtaq Rajput was similarly accused and tied to a tree and stoned to death in Pakistan. Earlier this year in Iran, it was reported that Javad Rouhi was tortured so severely that he could no longer speak or walk. He was sentenced to death for apostasy and later died in prison under suspicious circumstances.

But while we might anticipate that the desecration of the Quran would be proscribed in Islamic theocracies, it is troubling to see similar laws being passed in secular nations such as Denmark. The government had not been so faint-hearted when faced with similar problems in 2005. After cartoons of the Prophet Mohammed were published in Jyllands-Posten, a global campaign from Indonesia to Bosnia demanded that the Danish authorities take action. The government stood firm and the judicial complaint against the newspaper was dismissed.

In a free society this is the only justifiable response, albeit one that takes considerable courage. And the climate of intimidation that has descended since is a product of our collective failure to defend freedom of speech against the demands of militants. When the Ayatollah Khomeini pronounced his fatwa on Salman Rushdie for his novel The Satanic Verses, one would have hoped for a unified front on behalf of one of our finest writers. Instead, much of the literary and political establishment abandoned or even censured him. In the Australian television show Hypotheticals, the singer Yusuf Islam, formerly known as Cat Stevens, implied that he would have no objections to Rushdie being burned alive.

That a work of fiction such as The Satanic Verses could not even be published today gives us some indication of the extent to which we have forsaken the principle of free speech. If we are so squeamish about the burning of Qurans, why were so many of us indifferent to the burning of Rushdie’s book on the streets of Bolton and Bradford? Yusuf Islam’s remark about the author’s immolation might have been flippant but, as Heinrich Heine famously wrote: “Where they burn books, they will in the end burn people too.”

The ceremonial burning of books in Germany and Austria in the Thirties has ensured that the act will always have a unique charge, and a disquieting, visceral effect. It is why, for instance, the most memorable scene in Mervyn Peake’s Titus Groan is when the villain Steerpike sets fire to his master’s library. It is a gesture designed to repudiate the very heights of human achievement, to hurl his victim into a spiral of despair. When Rushdie saw his own novel publicly incinerated, he confessed to feeling that “now the victory of the Enlightenment was looking temporary, reversible”.

The burning of the Quran leaves many of us similarly troubled. We do not need to approve of the contents to sense that the destruction of a book is symbolic of a desire to limit the scope of human thought. When activists post footage of themselves gleefully setting fire to copies of Harry Potter, one cannot shake the similar suspicion that they would happily substitute the books with the author herself.

But while many of us find the burning of books instinctively rebarbative, to outlaw this form of protest is essentially authoritarian. And to reinstate blasphemy laws by specifying that only religious books are to be protected is fundamentally retrograde. Of course, such laws already exist in most Western countries in an unwritten form. In March, a 14-year-old autistic boy was suspended from his school in Wakefield, reported to the police, and received death threats after he accidentally dropped a copy of the Quran on the floor, causing some of the pages to be scuffed. He may not have committed a crime, but many people behaved as though he had.

And the same unwritten laws are in force in the fact that few would be brave enough to publish cartoons of the Prophet Mohammed after the massacre at the offices of French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo in 2015. Five years later, the schoolteacher Samuel Paty was beheaded on the streets of Paris simply for showing the offending images during a lesson on free speech. Closer to home, a teacher at Batley Grammar School in West Yorkshire is still in hiding after showing the images to his pupils and stirring the ire of a righteous mob.

The failure of the school’s headmaster, as well as the teaching unions, to support this man against the demands of religious fundamentalists is revealing. Why must those who claim to be defending the dignity of Muslims treat them as irascible children? At the same time, as Sam Harris recently pointed out, there is an oddity in the fact that so many Muslims do not appear to be alarmed that “their community is so uniquely combustible”.

The bitter reality is that terrorism works, particularly when so many governments across the Western world are seemingly willing to fritter away our bedrock of liberal values. This has been actuated, in part, by an alliance of two very different forms of authoritarianism: ultra-conservative Islamic dogma and the safetyist ideology of “wokeness”. The latter has always claimed that causing offence is a form of violence, and the former has been quick to adopt the same tactics. This is why protesters outside Batley Grammar School asserted that the display of offensive cartoons was a “safeguarding” issue, and the Muslim Council of Britain criticised the school for not maintaining an “inclusive space”. The same censorious instincts have been updated, and are now cloaked in a more modish language.

In a civilised and pluralistic society, the burning of a holy book might provoke a variety of responses — anger, disbelief, or just a shrug of the shoulders — but it should never lead to violence. Back when The Onion still had some bite, the website satirised this “unique combustibility” through the depiction of a graphic sexual foursome between Moses, Jesus, Ganesha and Buddha. The headline said it all: “No One Murdered Because Of This Image”.

Freedom of speech and expression still matters, and if that means a few hotheads and mini-Tamburlaines might burn their copies of the Quran then so be it. It is unfortunate that we have reached the point where Islam must be ring-fenced from ridicule or criticism, whether due to fear of violent repercussions or a misguided and patronising effort to promote social justice. But for this state of affairs we ultimately have only ourselves to blame, and in particular our tendency to capitulate to religious zealots when they seek exemption from the liberal consensus.

==

#Andrew Doyle#blasphemy#blasphemy laws#quran burning#quran#islam#islamic authoritarianism#authtoritarianism#i'm offended#offended#religious authoritarianism#free speech#freedom of speech#freedom of expression#criticism of islam#religion#religion is a mental illness

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

“ i’ll be here. when you’re ready to talk. ”

more prompts for your feels.

'Will you? You did not seem too eager to truly hear what I had to say back then. You did not even give me a chance.' And the next thing he knew, Diluc's divine punishment was his to receive. Perhaps a cue for him to start atoning for his sins.

That is what goes through his mind as Diluc presents his pitiful attempt at commiseration. Although he wishes to let his true feelings transpire, he finds ( with great difficulty ) a will powerful enough to yet again veil his inner thoughts. With how much frequency does this occur...? He has lost count.

...Does he even possess the right to blame Diluc for his own anger and heartbreak? Although such feelings still linger, he often has to call himself to reason: no, he does not. Kaeya must side with the redhead and admit that the timing had been atrocious. Everything that day had been awful. And yet... Yet his selfish, guilt-ridden self had succumbed to his own need of coming clean. His confession had taken priority over Diluc's own feelings. Kaeya did not give him the time, the space, or the support Diluc had required. An amateur mistake, howbeit it seems that it is a vicious circle Kaeya often finds himself in.

Even now, he is being selfish about the entire ordeal. Diluc had interpreted his words as pure betrayal, the accusation loud and clear, although words had not been needed. But in Kaeya's mind, he had been trying to do the exact opposite --- he had tried to show Diluc that he trusted him. He had wished to come clean, he had wished to confide in Diluc, he had wished that Diluc would love him for who he truly was. And all he met was outright rejection and abandonment. Diluc had repudiated Kaeya's entire existence and then left. For years. And that had seemed like an eternity.

What guarantees him that the pattern will not once again repeat itself in the weaves of destiny? No. He refuses to even consider that option. He cannot bear to witness; to live through it ever again.

A shrug of arms, lips curving upward, disposition calculated. He always has to carefully think about how he presents himself. He has to have control.

«Worry not, Master Diluc. My life is not as tragic for me to pour my heart out to you». An obvious lie that both are aware of. But why bother? Kaeya refuses to open up again. He is so heavily afraid of what will happen if he does. And he does not wish to cause Diluc any more concern. Or pain. Or anger.

Offering nothing else in response, he brushes off the figurative helping hand Diluc extends.

#{{ ragbros: a vicious circle of 'I feel so guilty to have caused him harm; it can be hard to face him' and also --- }}#{{ 'still; how could he ever have done this to me???? How could he... betray me like this....' }}#{{ it really goes both ways. }}#{{ We love!!!! complicated relationships!!! in this house!!!! }}#dilucisms#【 ic | fool you once; fool you twice. 】

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Random reactions to 3Hopes spoilers under the cut.

Just spent the last 1.5hrs clutching a plushie and watching spoiler cutscenes to 3Hopes. I wonder if I just watched someone with an advanced copy of 3Hopes, since it releases tomorrow, or if I was watching an English version from someone in Europe who's a few timezones ahead, or if the Demo really went all the way to the end of Part 1 of the story. o.O?

That last part, really got to me. Not just that Claude had to kill his brother Shahid, when Claude's whole ethos is for people to come to some kind of understanding and acceptance or at least tolerance of each other, rather than killing each other. But after defeating Shahid a 2nd time, Claude felt he had to kill him. I don't know why he couldn't just take him prisoner, at least for the sake of adhering to his ideals of working out compromise and understanding between people, even if it took lots of time and work, or at least to adhere to his ideals that people shouldn't kill each other just because they have differences. Maybe it would have just incited an Almyran rescue-army to retrieve Shahid and perpetuate more war? Not taking the non-lethal path, repudiating his own ideals, must have really hurt Claude. You could hear it in his voice during the victory party. He had that same tone in FE3H while looking at the stars, asking Byleth to "talk with me for a while?", and confessing to feeling helpless/hopeless/alone. ;~;!!! I'm sure it hurts Claude, chips away at his Hope, each time he has to kill someone, rather than adhere to his ideals of people talking things out, coming to understanding and tolerance of each other, people overcoming their differences, and getting along. After all, the only reason he's survived with his goodness in tact, without becoming bitter and vengeful towards the world, is because he resolved to dream in a better world and maintain hope in others, for everyone's potential to work out their differences, understand, and accept each other. Claude can't stamp that Hope out so lightly, without trampling on his own will to survive/live. Maybe Shahid was too much a liability, in either his resolve to kill Claude or spill his secrets? But reasons for liability like that, shouldn't be enough for Claude to trample on his own ideals that feed his Hope. I wonder if he's sad because some part of him realizes that, even after the decision he made at the time to kill Shahid, was to put more weight in protecting himself from Shahid's threat, rather than adhering to his ideals. It really makes Claude's line from the 3Hopes trailers and that Shahid-killing scene even more ominous. If Claude resolves to see "hesitation to kill opposition" as a "mistake" that "now that I know, I won't make the same mistake again", then how much will Claude's ability to compromise with others erode? How much will he stop trying to work with others to understand him and resolve their differences, in favor of ending things with violence/death instead? Will Claude be able to maintain his Hope in other's potential for cooperation/goodness? Will he go down a slippery slope of killing threats instead of working with opposition, until differences are resolved? He's already become king of Leicester. Will he stop working with others altogether? Even Arval and Shez have noted that they may never get through his emotional defensive wall. If Claude never opens up, as he did after that year at the Academy and interactions with Byleth, what if he gives up on his dreams of fostering openness between people, for understanding differences and tolerance of diversity?

For a long time now, I've worried that 3Hopes will all have bad endings, to justify winding back time, so that Shez can disappear as was "destined", and Byleth can take their place in Fodlan's unification history. I keep worrying that something will push Claude in the wrong directions, so that his dreams and talk of unifying people, "erasing borders", and allyship, will morph into conquest and absorbing Fodlan into Almyra or Almyra into Fodlan. The same philosophy to make Fodlan and Almyra become one nation, instead of allowing them to maintain their differences, could slip into homogeneity, rather than an appreciation of diversity. But maybe I'm catastrophizing again. I hope so. I don't want Claude to give up on his dream, and allow his hope in others to erode away. A ruler who only feels secure when all other people are under his rule, will do nothing but try to conquer EVERYONE, all nations, because no other nation independent of his would be allowed to exist. o_o

Otherwise, I really enjoyed finally seeing Nader and Holst being sworn-brothers. They were really funny. Plus, now Hilda can have 2 overbearing brothers. LOL

And the way Claude was able to explain how he knew Nader without giving up his secret, even then, was impressive. Even Lorenz mostly bought it. ^_^

I also watched the paralogue confirming what we all suspected about Raphael's parents' deaths. We got a little more verification that it was Count Gloucester's doing. He hired the mercenaries that ultimately killed Raphael's parents and Claude's Uncle, but in the end, the paralogue also kind of absolved Count Gloucester. Curious. The story made a point to suspect the messenger from Count Gloucester, who sent the orders to the mercenaries, to attack all merchants who approached Riegan territory. The story made a point to make it seem that Count Gloucester didn't know anything about that messenger. Makes it sound like Count Gloucester is innocent, and maybe that messenger was actually an Agarthan spy or something. But Count Gloucester could have easily been lying about not knowing about the messenger and those "fake orders". Count Gloucester is already so secretive with even his son and has demonstrably shown to be an expert at speaking roundabout vs cooperating with Claude. Count Gloucester's house was considered a candidate to take position as the house to lead the Alliance, after Riegan, according to Lorenz's/Claude's Support in FE3H, I believe. Count Gloucester has been after leadership of the Alliance so much, that he raised Lorenz to consider himself next in line as the Alliance leader and to constantly undermine Claude in FE3H. With Claude's uncle Godfrey Riegan dead, Count Gloucester could have very well taken control of the Alliance, despite Holst's popularity for leadership position, since Host has been stuck protecting Fodlan's Locket. The one to benefit most from Godfrey's death would have been Count Gloucester...up until Claude suddenly showed up. I still suspect him. I'm not ready to just blame it all on some Agarthan spy who escaped the Empire.

But it was nice to learn that Godfrey died trying to defend Raphael's parents. At least he seemed like a good guy.

Also watched that meeting between Edelgard and Claude where they formally made an alliance. She spoke with this condescending tone the entire time that just made her super suspicious. And indeed, Claude did say he expected the Empire to be using them, but at least he would be using them in return.

I just hope part 2 follows through on that clip from the trailers, where Claude shot an arrow between Edelgard and Dimitri fighting. I hope part 2 has Claude trying to get all the countries in Fodlan to work together and resolve their differences without violence. ...Maybe Claude will fail at that by the end of 3 Hopes. But I have been suspecting 3 Hopes to have bad endings in all its routes, to motivate Shez to allow Byleth to usurp their place.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Albus Dumbledore and the Destruction of the Parent

Part 1 : Laying the groundwork

In one of the final chapters of the Harry Potter series, when Harry finally gets to meet Dumbledore again after his sacrifice, the extent to which the past haunts our favourite headmaster is finally revealed to our hero. Indeed: not only does Dumbledore fully confirm to the boy that he was a neglectful parent (when he was put in charge of his extremely sensitive little sister after both of their parents had left the house), but he also even suggests/insinuates that he may very well have been the one out of Grindelwald and Aberworth to have accidently struck her with his hand and caused her tragic death during their duel.

One question that readers may immediately ask themselves is why the old wizard is telling any of this to Harry? Indeed: by this point in the story it has almost been a year since the headmaster has been killed at the hands of Severus Snape, and Dumbledore cannot possibly still hold on to the notion or hope that he will be able to influence Harry. His complete acceptance of this fact can be shown straight after this confession when he states wholeheartedly that Harry’s choice of staying here or of returning to the Living World and trying to defeat Voldemort is completely “up to him” (590). It is almost as if a responsibility or pressure has now been lifted from our mentor’s shoulders.

In an interview with the writer of the fifth Harry Potter movie, Michael Goldenberg states how one of the major themes that he noticed within the novels and which he then wanted to transfer into his own script was the increasing “need” for Dumbledore “to come down from his pedestal” so that Harry may be “disillusioned” and “grow up and take on the responsibilities that he needs to take on” (CMU). This particular moment in one’s life is described elsewhere as “when [one] see[s] the authority figure [that they’ve] either idealized or demonized revealed as more complicated” and/or “[realize] that [their] parents are normal, flawed human beings” (Salon). But the question of how it could be important for Harry’s maturation is never addressed.

In order to answer this question, one must properly define what Harry is facing within the story. Indeed: after but a cursory glance at the scholarship surrounding the series, it is clear that “[our main protagonist’s] battle with Voldemort may be seen as an internal conflict between aspects of his own psyche, culminating in Voldemort’s defeat and the repudiation of those aspects he represents” (Rosegrant, 11). Moreover, the fact that JK Rowling has chosen teenagehood as the setting/backdrop for this conflict equally should not be seen or interpreted as a coincidence. As Call and McAlpine go on to state: “Much of Harry’s journey through adolescence is a struggle to reject the part of himself that links him to Lord Voldemort” (Call/McAlpine, 76). This link is finally broken however when Voldemort inadvertently curses himself after Harry does a rebound spell.

What is especially significant is that not once in the story does Harry play into his enemy’s game (even when he is tempted). In the end, it is this very difference between the two characters – how one will never submit to the lowest depths of trying to kill the other – which ultimately decides/dictates the winner. You may naturally wonder, then, where does Dumbledore fit in all of this? Indeed: if the main battle of the story can only be fought inside/within Harry’s own psyche, then what even is Dumbledore’s role/function/purpose towards our main character? And, what’s more, how does this go beyond the fact that he will almost always just be accepted as an “influential parental figure” (Reynolds, 272)? In other words: how does Dumbledore’s ‘status’ as a parent have any sort of connection with Voldemort himself (- the very thing that Harry must defeat)?

This question becomes even more important when one observes the specific studies that have already been made on the character. Indeed: it is almost unanimously agreed amongst scholars that the fact that Dumbledore chooses to withhold information from Harry concerning Voldemort and the Prophecy that “either must die at the hand of the other for neither can live while the other survives” must mean that the need to defeat Voldemort belongs to Dumbledore and not Harry. In her paper titled ‘Doubting Dumbledore’, Jenny McDougal describes the old wizard’s manipulation and deceit towards Harry as proof of a “larger endgame” at work (McDougal, 162). Alicia Wilson-Metzger goes on to state that Dumbledore wants to “[shape Harry] into [his] ultimate weapon in the war against Lord Voldemort” (WM, 15). Here, Voldemort is clearly separated from Harry’s psyche and stands out as a character of his own.

However is this the only possible interpretation? Indeed: if we are truly to see Voldemort as just another part of Harry’s psyche – as I hope to have already demonstrated to you within this essay – then it is only natural that the Prophecy’s true intended message should change as well. Now, instead of talking about actual death, what the Prophecy could actually be saying is that in order for Harry’s “soul” to remain “whole and untarnished” he must kill or destroy that Dark part within himself (Los, 33). With this new perspective, it might then equally be possible for us to consider Dumbledore’s secrecy towards Harry in a new light and even start to be able to justify it. Now, instead of “offering [up]” Harry “as a sacrificial lamb to Voldemort” by withholding information from him until the very last moment, what Dumbledore could in actual fact be doing is protecting the boy from knowledge that might otherwise have a negative impact on his growing-up process (WM, 294). In other words: Dumbledore might actually be carrying out his parenting duties.

This may help to explain why it is so important for Dumbledore to come down from his pedestal in order for Harry to mature properly. Indeed: in progressively removing/detaching himself from our main hero, Dumbledore is essentially trying to break away at the “great” and “infallible” image that Harry has created for himself of this old man, all the while being fully aware that it might cost him the affection of someone that he holds very dear (Woodford, 71). By the end of the story, when Dumbledore finally confesses to the boy wizard about his troubled past, one ultimately gets a sense that the headmaster’s job as a parent is finally complete. Now, the old man has completely unveiled himself before Harry, and the latter’s romanticized image is broken.

Part 2 : Raising the question

Now that we have established how Dumbledore carries out his parental role towards our favourite student, the question will naturally become why the old man even chooses to go through with this process at all / in the very first place (since as I have already previously stated one of its innate/ultimate requirements/characteristics will invariably be that Dumbledore shall be obliged to gradually separate himself from someone that he self-admittedly “[loves]” and “[cares] about” (Book 5, 772)). And so in a way one could say that there is not much the poor, old headmaster could possibly stand to gain from following through with it. This is a particular question that has never been asked before, and which I would specifically like to address within my essay.

In the first book of the series, there is a scene where Harry chooses to sneak off during the middle of the night under his Invisibility Cloak so that he might have a glimpse of his dead parents in the Mirror of Erised (an object which is said to display/show the “deepest, most desperate desire of our hearts” (Book 1, 229)). However, after the little boy is found by Dumbledore, the two characters hold a small conversation on the dangers of wanting too much out of life and by the end of it the former is asked by the latter “not to go looking for [the object] again” (230). But as Harry is just about to exit the room however, a curiosity seems to wake up inside him and he dares to ask his headmaster what the Mirror would display if he himself were ever to look into it. As readers we may see this as our first good opportunity to learn about Dumbledore, a character which to that point we have not been given much information about.

Much to our surprise and dismay however, it immediately becomes evident to us that the old wizard is already well-educated on matters of self-protection from potentially revealing sources or leaks of information to others. Dumbledore manages to use his wit and cleverness in order to successfully avoid having to properly answer Harry’s question: “I see myself holding a pair of thick, woolen socks” (Ibis). His insincerity with this quippy remark is even spelt out to us later on by the author herself when she makes sure to include: “It was only when he was back in bed that it struck Harry that Dumbledore might not have been quite truthful” (Ibis). However since by this point the headmaster still represents the little boy’s hero, this action is equally justified by our narrator within the very same sentence on the terms that it had been “quite a personal question” (Ibis).

Harry and the readers unfortunately have to wait until the end of the series – during that famous confession scene when Dumbledore wishes he could go back in time after having “[neglected] the only two members of [his] family left” – in order to finally get an honest answer (Book 7, 586). In the end, it is the very idea that our headmaster wants exactly the same thing as Harry – i.e. the notion of having a full family – which begins the process of humanifying him in our minds. For the first time in the whole story, Dumbledore releases himself from this parental role/position of superiority that he has always and dutifully exercised over Harry. Now, he is not the one to give advice or of focusing on the other’s weaknesses anymore. Both characters are to be seen on the same terms and/or equal grounds from this moment on.

What can these passages both at the beginning and at the end of the story reveal to the readers? Namely the extent to which a feeling of parental responsibility towards Harry can govern/control Dumbledore’s own words and actions. It will be so strong in fact that Dumbledore will not even be able open up about himself to his favourite student until he absolutely knows for sure that the boy will be mature enough to take/hear it (so as to not hinder his development process). This is why Dumbledore’s process of stepping down from his pedestal within the eyes of Harry Potter cannot be done too early but must be done gradually. Harry himself only understands the need for such a process until the very end of the story, which explains why as the books go by the reader will often find him to be getting more and more angry and disillusioned with the headmaster.

And so now I have arrived to the main challenge of my thesis/essay. If I want to answer the question of why the character of Dumbledore feels such a need to serve or act as Harry’s parent within the novels, then I will invariably have to try and separate or detach him from that very association in the first place (in order to have a chance of unearthing the ‘human’ underneath). This means that any decision or utterance that our favourite headmaster has made which could possibly be connected or tied to his role/function as a parent will eventually have to be discarded from my analysis. Hence why I have chosen ‘Albus Dumbledore and the Destruction of the Parent’ as the title.

#harry potter#dumbledore#parenting#voldemort#adolescence#bildungsroman#coming of age#growing up#jk rowling#essay#literary criticism

1 note

·

View note

Text

you…

i’m a complex human being

contradictory is my seed

i thought there couldn’t be

a bigger confusion in its existency.

but then of course, our lives intervened.

you came as no surprise,

nothing of a facade i hadn’t seen

yet slowly you unveiled most parts of me,

i always kept concealed beneath .

repudiating were my words

tricky to read was my expression

to vigorously test your mind,

but captivating were your eyes

with each response you would voice

as you left my essence

shockingly, in complete rejoice.

deliberately went our journey

prudently caressing our profound souls.

until the pace became unbearable

as we ached wanting more.

the need was unrecognizable

strange even in its own kind,

therefore the pain infuriated

attacking the poor, “dim light”.

needles pecked my wary heart

quite again it came as no surprise,

but this time a well enraged from within

and it couldn’t find a way to stop.

my judgment was a haze

i reconcile that to be best,

for your presence was so troubling

but your absence even more of a stress.

hence, i would rather lose my mind

on how tacky your breath sounded

than to never smell again

your odor, strong and enchanted.

the cold eventually swept by

in between blossoming leaves

lingered your voice on how you missed

my acquaintance in the midst .

frankly, it was almost all i needed

to spark the courage and depart

of the grand awaited affirmation:

you were engraved in my heart

on extents no friend should overcome.

resentment abruptly arose

once your hands came too close

people who weren’t deserving

of your brilliant conferring.

although utter disbelief berated me

on why my feelings came in the loose,

your touch grew more than thrilling

and your voice kept me seduced.

my name swirling in your mouth

was a torment to endure

knowing chances of acting upon

were a sheer impossibility.

now that we’re alone

conversing deeper than we ever have,

how can motions of powerful assertion

curve later into seeming refutation?

what ludicrous creatures are we

to interact in parallel means?

how could we have trespassed so far

to yield each others needs?

my internal struggle to confess

your ownership to my many thoughts,

failing on being forthright

they twist in abstracts manners

are paraphrased in even more so.

and quite shamelessly

you reciprocate the confusion

the almost madness.

oh this delirium regarding you!

your bewilderment and mine

are immensely endorsing, consuming.

breathless in anticipation i reside

to have the mystery solved and restored

of what these feelings of yours are,

but most importantly

wether this mere “friendship”

is to ever go up aboard

#poetry #poem #poems #book #books #writing #writer #amateurwriting #him

0 notes

Text

By Lucinda Rosenfeld

Not long after I became my professor’s research assistant, I told him that I sometimes threw up what I ate. A junior at Cornell, I had just turned twenty. X, as I’ll call him, had hired me in conjunction with the “work-study” program, which was available to students who received financial aid. He was almost a decade and a half my senior. He was also married, but his wife was teaching and living elsewhere. X himself was on leave from another élite university. It was 1990. George H. W. Bush was in the White House. And you could still smoke cigarettes anywhere you wanted to.

Sometimes, when I visited X in his office on the top floor of a Victorian building near the Arts Quad, as I began to do after class, he’d ask if he could have one of my Marlboro Lights. I had started smoking a year before as a way of dealing with the nagging questions of what to do with my hands, how to suppress my appetite, and, above all, how to give myself the appearance of someone who stood aloof from the petty squabbles of everyday life—though nothing could have been further from the truth.

I remember following up my confession with a question: “Do you think I’m pathetic?”

“Do you want me to think you’re pathetic?” In the manner of a therapist (or Socrates), X often replied to my questions with other questions.

“No.” I recall laughing to break the suddenly sombre mood—also with relief that he didn’t seem to have judged me.

After a smoke-filled pause, he told me that someone he knew was making a film about the topic.

I never found out who the filmmaker was, but the idea that an associate of his regarded the topic as worthy of further inquiry made me feel a little less ashamed.

Why, after lengthy deliberation, I’d decided to disclose such a closely held secret to someone who was neither a trusted friend nor a mental-health professional was a more complicated question. On account of his age and perceived authority, I suppose I saw X as a substitute parental figure, especially since confiding in my own parents had proved to be a fraught activity. I think I had the idea that, if I could get X to worry about me, he’d want to take care of me. Which was the fantasy that underpinned all my other fantasies, even as I lived in fear of appearing needy.

But that was only part of it. X had a slow and measured manner of speaking that put me at ease, along with a calm confidence that I lacked and found magnetic. He was also tall, with tenebrous good looks, and he laughed easily, as if the very business of life were an elaborate joke. Really, I thought I’d never met such a clever and glamorous man and I made no effort to hide the crush I had on him. I attached flirtatious notes to the piles of books he asked me to retrieve for him at the library, and sat down right next to him at the polished-wood table where he conducted his seminar.

I was also angry at my family and the pressure I felt all of them put on me to be “perfect” and impressive—or, at least, I was as angry at my family as I was at myself for not being those things—and therefore all the more drawn to X’s radical politics and irreverent attitude, which seemed to repudiate everything that my high-culture-loving parents had raised me to revere. My father was a cellist, and my mother a writer of art-related books.