#SaritaDrawsPalaeo

Text

Pride dino #7: Aromantic Sinosauropteryx

—-

Oof, sorry this series is taking so long 😓 This has been a very busy year for me! Hopefully by next year I’ll be able to finish it. But for now… I guess I gotta prepare for Archovember once again…

#my art#SaritaDrawsPalaeo#Sinosauropteryx#Sinosauropteryx prima#aromantic#aromantic pride#aro pride#aro flag#aromantic flag#LGBTQIA+#LGBTQ+#LGBTQ#LGBT#LGBTQIA

318 notes

·

View notes

Text

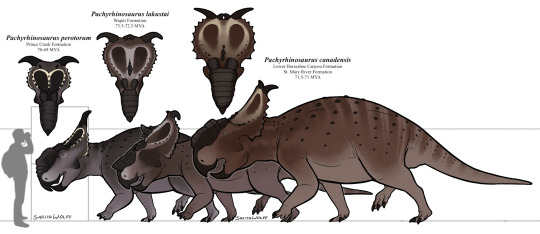

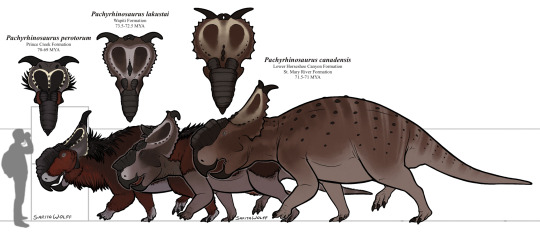

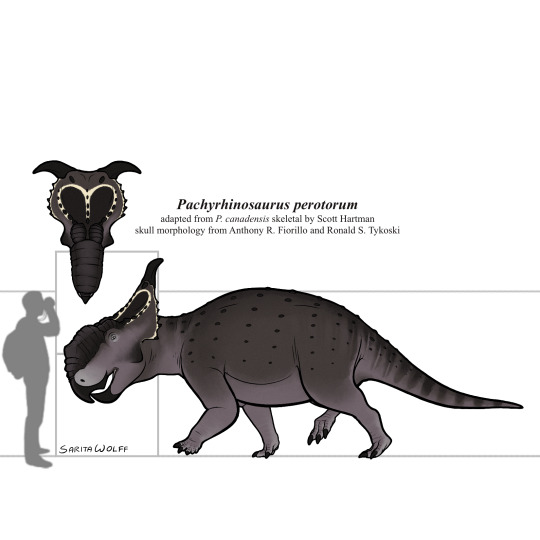

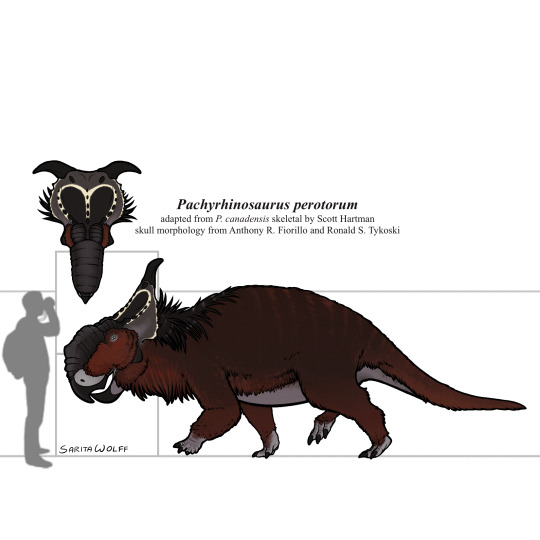

A Patreon request for rome.and.stuff (Instagram) - Pachyrhinosaurus perotorum… that I went a bit overboard with lol. I’ve been waiting for an excuse to draw my favorite ceratopsian, and to digitally adapt my old Pachy marker drawing design.

So! Pachyrhinosaurus! As seen above, there were three known species of Pachyrhinosaurus, living in different locations and eras in Late Cretaceous North America.

The oldest, P. lakustai, was native to the Wapiti Formation of Alberta and British Columbia, Canada. It’s known for the extra spikes it has at the center of its frill.

The slightly younger P. canadensis was native to the lower Horseshoe Canyon Formation and the St. Mary River Formation of Alberta and northwestern Montana. It was the largest of the three.

The youngest, P. perotorum, was native to the Prince Creek Formation of Alaska. As this ceratopsid seemingly stayed put during the long, dark, cold Alaskan Winters, it likely had adaptations for keeping warm.

The depiction of a “woolly” Pachyrhinosaurus was first popularized by Mark Witton as a speculative work, but the trope has prevailed. While many paleontologists find a heavy feather covering on a centrosaurine to be highly unlikely, and maintain that the animal’s size and homeothermy would have kept it warm enough, we still have no skin impressions to suggest that P. perotorum was fully scaly. So a feather coating is not completely out of the question (though it is unlikely). Still, I love the look of a woolly Pachyrhinosaurus and how it challenges our previous conceptions of non-avian dinosaurs. Stranger things exist in nature. I had to include a “woolly” option, especially since I already use the guy as my avatar on my paleo Instagram account, SaritaPaleo.

Pachyrhinosaurus was particularly unique in that it seemingly traded off something that had previously worked for other ceratopsians, horns, for a large nasal boss instead. For Pachyrhinosaurus, a battering ram worked better than a sword.

It was herbivorous, using its strong cheek teeth to chew tough, fibrous plants. Perhaps during the dark and cold Winters, P. perotorum would have also dug for roots or even scavenged carcasses. At any rate, from observations of their unusually conspicuous growth banding, it appears growth for P. perotorum would have been stunted during the harsh Winter, but was extremely rapid in the warmer months, an adaptation for the Alaskan climate.

The tundra of the Prince Creek Formation housed a surprising amount of diversity. Pachyrhinosaurus perotorum would have lived alongside smaller ceratopsians like Leptoceratopsids, as well as other ornithischians like the pachycephalosaurine Alaskacephale and the hadrosaurid Edmontosaurus. Theropods such as Dromaeosaurus and Saurornitholestes, as well as a yet unidentified giant Troodontid, lived here as well. P. perotorum’s main predator would have been the tyrannosaur Nanuqsaurus. Small mammals were also somewhat common here, such as Cimolodon, Gypsonictops, Sikuomys, Unnuakomys, and an indeterminate marsupial.

(Btw, the request tier for Patreon starts at only $5 a month. 😉 Link is pinned at the top of my blog.)

#my art#SaritaDrawsPalaeo#Pachyrhinosaurus#Pachyrhinosaurus perotorum#Pachyrhinosaurus lakustai#Pachyrhinosaurus canadensis#Centrosaurines#ceratopsians#ceratopsids#ornithischians#dinosaurs#archosaurs#archosauromorphs#reptiles#Prince Creek Formation#Wapiti Formation#Horseshoe Canyon Formation#St. Mary River Formation#Late Cretaceous#Canada#United States of America

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

Patreon request for Magno/rome.and.stuff - Ichthyovenator laosensis!

Icthyovenator is a Spinosaurid from the Early Cretaceous of Laos. Known only from fragmentary material, it seems to be unique among Spinosaurids for the strange divot in its spine. (In this depiction, I’ve also added another small divot further up the back; however, we don’t have that much of the spine, so this is purely speculative.) This strange sail could have been used for display or species recognition. Like other spinosaurines, Icthyovenator was likely adapted for a semi-aquatic lifestyle, hunting aquatic prey like fish, amphibians, and small dinosaurs. Like Spinosaurus, it had unusually tall vertebral spines on its tail which likely aided in swimming.

While it certainly wasn’t snacking on sauropods (except possibly via scavenging), it lived alongside large ones like Tangvayosaurus. Trackways in the Grès Supérieurs Formation belong to sauropods, iguanodontians, and neoceratopsians, though fish and turtles make up the majority of this ancient habitat.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

This was a nice warmup for Archovember, and it’s also good to have another Spinosaurid under my belt. I should redraw Baryonyx and give it a size chart. Maybe someday I’ll have enough to make a full spinosaurid comparison chart. 🤔

Btw, the request tier for Patreon starts at only $5 a month. 😉 Link is pinned at the top of my blog.

#Ichthyovenator laosensis#Ichthyovenator#Spinosaur#spinosaurid#theropods#dinosaurs#archosaurs#SaritaDrawsPalaeo#saurischians

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

And to finish off the dromaeosaur series: the obligatory size chart. I figured some of the poses would be misleading if I put them in a size chart… so I redrew everything 🙃. Neutral poses for the first one, and then my original poses for the second.

All the neutral poses were mostly traced from skeletals, by Scott Hartman (Austroraptor, Buitreraptor, Microraptor, Velociraptor, Deinonychus, Sinornithosaurus, Utahraptor, and Dromaeosaurus), M. Auditore (Halszkaraptor), Ashley Patch (Zhenyuanlong), Xing Xu and Zichuan Qin (Zhongjianosaurus), and Gunnar Bivens (Saurornitholestes). Changyuraptor had to be estimated based on the fossil slab as no one (except Peters of course) has made a skeletal of it yet.

~~~

And that’s it for my Dromaeosaur series (though I may draw more in the future of course.)

Nex up, I’m thinking either Troodontids or Oviraptorines. Both are very special to me, so I shall probably put it to vote on my Instagram.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

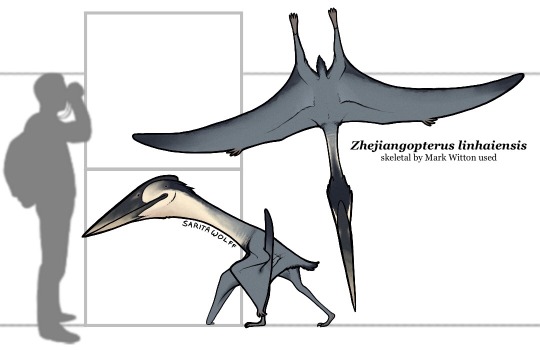

#Archovember Day 8 - Zhejiangopterus linhaiensis

Azhdarchids are known as the largest flying animals of all time, the last great stand of the pterosaurs before . They contained mighty giants like Quetzalcoatlus and Hatzegopteryx, who ruled the skies of the Late Cretaceous. But not all azhdarchids were flying carnivorous giraffes. Some of them were downright tiny, while others reached a more modest, respectable size. Slightly larger than a female Pteranodon, Zhejiangopterus linhaiensis was one such “moderately large” azhdarchid.

Zhejiangopterus lived in Late Cretaceous China and is so far the most complete azhdarchid known, making it very influential to our understanding of this amazing family of pterosaurs. As several specimens have been uncovered, it was probably fairly common in the Tangshang Formation. It lacked the bony crest seen in many of their relatives, instead opting for a long, straight, graceful profile. Like other azhdarchids, Zhejiangopterus were likely terrestrial stalkers similar to storks and ground hornbills, only using their wings to escape predators or move to new hunting grounds.

Not many other animals have been found in the Tangshang Formation. Alongside Zhejiangopterus, there is only the avialan Yandangornis (whose eggs and chicks and perhaps even adults, if they could catch them, could have been prey for the pterosaur) and an unnamed therizinosauroid. However, living in Late Cretaceous China, it could have also come across the titanosaur Dongyangosaurus further South, and further inland: the ankylosaur Gobisaurus, the pachycephalosaurid Sinocephale, the ornithomimid Sinornithomimus, the carcharodontosaurid Shaochilong, and the mysterious theropod Chilantaisaurus. No doubt there were also plenty of lizards, snakes, mammals, amphibians, and small dinosaurs hiding in the coastal grasses, ready to be nabbed by the dragon of Zhejiang.

#my art#SaritaDrawsPalaeo#Zhejiangopterus#Zhejiangopterus linhaiensis#azhdarchids#pterodactyloids#pterosaurs#archosaurs#archosauromorphs#reptiles#Archovember#Archovember2023

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

Whelp we’ve got about a week and a half til November (aaaaaah), so I guess I’ll post this year’s Archovember list now!

It’s a bit dinosaur-heavy this time, but there are a lot of species I’d really like to try my hand at! Also, we have two leptoceratopsians and two Araripesuchus species. I thought it would be interesting to compare and contrast these species within the same month, so I hope it doesn’t get /too/ repetitive!

For new folks: this is my “Draw Dinovember” list that I expanded out to include other archosauriforms. I started doing this a few years ago to challenge myself to draw species I’ve never drawn before and/or ones that don’t get a lot of attention. Feel free to join in! You can do the whole list, just the dinosaurs, just the pterosaurs, just the pseudosuchians, just your favorites, just ones you’ve never drawn before, roll a D20 and a D10 and draw the sum of whichever numbers you get, etc. Just make sure they’re posted on or after their specific day so I remember to share them on my blog! You can use #Archovember or #Archovember2023, as those are the tags I follow. (Note that I and the whole Archovember event are usually a lot more active on Instagram so if you have an IG I encourage you to join in there!)

Anyway, here is the list in case the graphic is hard to read:

1. Your Choice!

2. Furcatoceratops elucidans

3. Tupandactylus navigans

4. Deinosuchus hatcheri

5. Herrerasaurus ischigualastensis

6. Lewisuchus admixtus

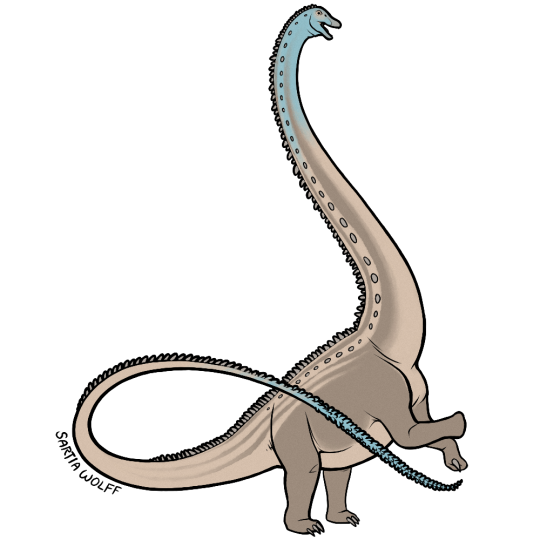

7. Supersaurus vivianae

8. Zhejiangopterus linhaiensis

9. Dynamosuchus collisensis

10. Megalosaurus bucklandii

11. Macrospondylus bollensis

12. Miragaia longicollum

13. Dorygnathus banthensis

14. Leptoceratops gracilis

15. Stagonolepis robertsoni

16. Shantungosaurus giganteus

17. Paleorhinus bransoni

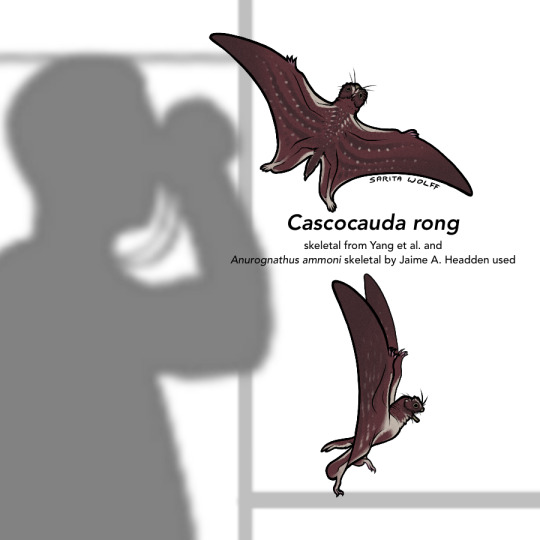

18. Cascocauda rong

19. Kelenken guillermoi

20. Prestosuchus chiniquensis

21. Yangchuanosaurus shangyouensis

22. Istiodactylus latidens

23. Kunbarrasaurus ieversi

24. Araripesuchus wegeneri

25. Tylocephale gilmorei

26. Ixalerpeton polesinensis

27. Udanoceratops tschizhovi

28. Tapejara wellnhoferi

29. Araripesuchus rattoides

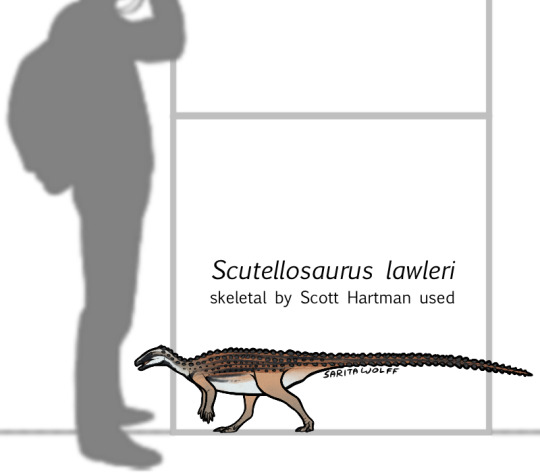

30. Scutellosaurus lawleri

One last note, and a warning I usually issue to new paleoartists: while looking for references for these species you’ll come across David Peters. His references tend to dominate search results when looking for less well-known species. They are also highly inaccurate, even the skeletals. So make sure you omit “The Pterosaur Heresies” and “Reptile Evolution” from your google search. If you have issues finding references, let me know and I can share what I’m using!

#my art#Archovember#Archovember2023#SaritaDrawsPalaeo#dinosaurs#pterosaurs#pseudosuchians#archosaurs#archosauriforms

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

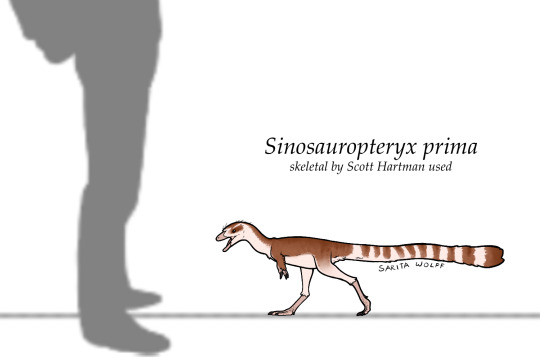

And the bonus Sinosauropteryx size chart!

#my art#SaritaDrawsPalaeo#Sinosauropteryx#Sinosauropteryx prima#Compsognathid#Theropod#dinosaurs#archosaurs#saurischians

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

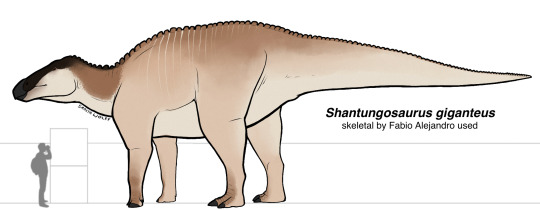

#Archovember Day 16 - Shantungosaurus giganteus

While hadrosaurs tend to be perceived as horse or cow-size, there were some intimidatingly huge members of the family. As the largest hadrosaur discovered so far, Shantungosaurus giganteus could reach 15 metres (49 ft) to 16.6 metres (54 ft) long and weigh an estimated 13 metric tons (14 short tons) to 16 metric tons (18 short tons). It lived in Late Cretaceous China, and would have filled a niche typically filled by sauropods in its ecosystem. As these dinosaurs have been found in a mass grave, it’s likely they also traveled in large, formidable herds. Shantungosaurus also had very large nostril holes which were probably covered by flaps of skin that could have inflated to amplify its calls.

Shantungosaurus lived alongside other hadrosaurs like Laiyangosaurus, Tanius, and Tsintaosaurus, all quite large animals but still overshadowed by Shantungosaurus. It would have also lived alongside a diverse array of ceratopsians like Sinoceratops, Ischioceratops, Zhuchengceratops, and Micropachycephalosaurus, as well as the ankylosaur Pinacosaurus and the oviraptorosaur Anomalipes. So far, only one sauropod has been found in this area, Zhuchengtitan, the tallest animal in its ecosystem… beating Shantungosaurus by a neck. The apex predator of this region was the tyrannosaur Zhuchengtyrannus. However, it’s likely would not have been able to take on an adult Shantungosaurus, but could have picked off young or sick individuals that strayed from the herd.

#my art#SaritaDrawsPalaeo#Shantungosaurus giganteus#Shantungosaurus#edmontosaur#hadrosaurs#hadrosaurids#ornithopods#ornithischians#dinosaurs#archosaurs#archosauromorphs#reptiles#Archovember#Archovember2023

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

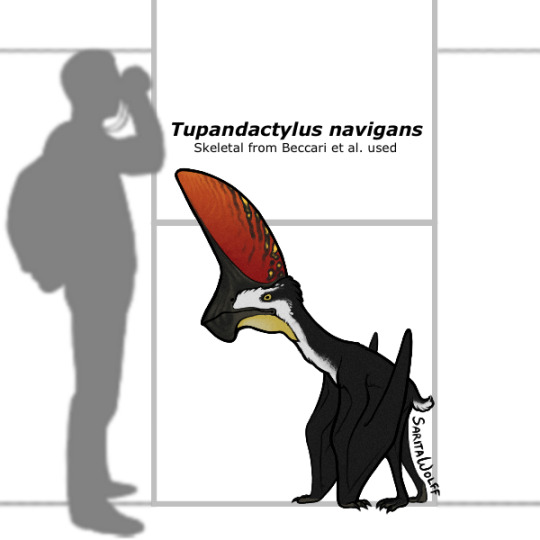

#Archovember Day 3 - Tupandactylus navigans

There were at least two species of the Tapejarid pterosaur Tupandactylus: T. imperator (who I’ve drawn previously) and T. navigans. Of the two, T. navigans is smaller, with a straighter, more upright crest. (A 2021 study suggests that the two species could actually represent sexually dimorphic members of the same species, but more detailed study is required to support this.) Either way, Tupandactylus is known for its huge keratinous crest, and T. navigans especially for its sharp shark-fin profile. This large crest likely limited T. navigans’ flight ability, relegating it to spending most of its time on the ground, only taking short flights to evade predators.

In 2022, A specimen of Tupandactylus imperator was discovered to have very complex branching pycnofibers (feather-like filaments unique to pterosaurs) that were much closer to true feathers than previously thought possible in pterosaurs. This could be further evidence that feathers are a basal trait to Avemetatarsalians. Also, similar to Anchiornis, Tupandactylus has been found with preserved melanosomes. However, paleontologists did not attempt to infer the color of the animal, but merely noted that the melanosomes were varied between the skin of the crest and the pycnofibers on its skull, probably providing some sort of contrast for the head ornamentation. No doubt imperator’s smaller cousin navigans was similar.

Living in Early Cretaceous Brazil, Tupandactylus navigans had a diverse array of frogs, lizards, and invertebrates to prey on, including moths, lacewings, mayflies, scorpions, and solifugids. T. navigans could have also preyed on small dinosaurs and their eggs, such as Enantiornithine birds and the compsognathid Ubirajara. T. navigans would have shared its environment with many other pterosaur species, such as its cousin T. imperator, Arthurdactylus, Aymberedactylus, Brasileodactylus, Lacusovagus, and Ludodactylus.

(As I’ve drawn T. imperator previously, but not with its own size chart, I’ve chosen to include it as a bonus here so the two species can be compared. I’ve also updated my imperator design a bit, as it was drawn before the 2022 study.)

#my art#SaritaDrawsPalaeo#Tupandactylus navigans#Tupandactylus#Tupandactylus imperator#tapejarid#pterodactyloid#pterosaurs#archosaurs#archosauromorph#Archovember#Archovember2023

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Archovember Day 27 - Udanoceratops tschizhovi

The leptoceratopsids are known for being small, pig-sized Late Cretaceous ceratopsians reminiscent of their more basal ancestors. But Udanoceratops tschizhovi took things to the next level, growing to the size of a hippopotamus, with the head and jaw strength to match. While assumed to be a herbivore like other ceratopsians, little is known about plants that grew in the Gobi Desert at the time of the Cretaceous, so it is unclear what types of plants it would have eaten. Its sharp beak, powerful jaws, and shearing/crushing teeth suggest a diet of relatively tough plants. Like other ceratopsians, particularly leptoceratopsians, Udanoceratops could have also opportunistically scavenged carcasses, nests, or even small mammals and young/weak dinosaurs for extra protein in its desert environment.

In the Djadochta Formation of Mongolia, Udanoceratops would have lived alongside the smaller, more numerous protoceratopsians Protoceratops and Bagaceratops. This was a mostly barren landscape, likely dotted by oases and arroyos that would have attracted smaller animals like nanhsiungchelyid land turtles, lizards like Gobiderma, frogs like Gobiates, crocodylomorphs like Artzosuchus, small mammals like Asiatherium and Mangasbaatar, and small theropods like the oviraptorosaur Avimimus. Udanoceratops was the largest animal around. Thus far, no predators large enough to take on an adult Udanoceratops have been found in its locality. The dromaeosaur Velociraptor could have snatched a baby Udanoceratops when the opportunity arose, but it would then risk the ire of this giant desert hippo with a staple remover for a head.

#my art#SaritaDrawsPalaeo#Udanoceratops tschizhovi#Udanoceratops#Leptoceratopsid#neoceratopsians#ceratopsians#ornithischians#dinosaurs#archosaurs#archosauromorphs#reptiles#Archovember#Archovember2023

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

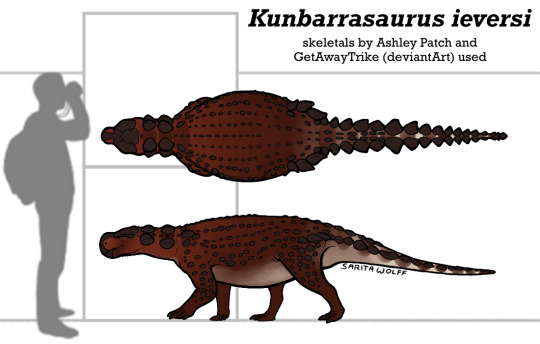

#Archovember Day 23 - Kunbarrasaurus ieversi

In the Early Cretaceous of Australia lived the small, basal ankylosaurian Kunbarrasaurus ieversi. Originally thought to be a species of Minmi, Kunbarrasaurus was eventually discovered to be a new genus of ankylosaur and renamed in 2015. One specimen is the most complete dinosaur fossil ever found in Australia, even containing gut contents! This Kunbarrasaurus’ last meal consisted of plant tissue fragments, whole fruits, and whole seeds. The tissue fragments are small and seem to have been nibbled or chopped by the ankylosaur. Unlike some other dinosaurs, it lacked any gastroliths, leading paleontologists to believe it had a more sophisticated method of grinding up its food.

Kunbarrasaurus fossils have been found in marine sediment, so they were likely swept out to the shallow inland sea that covered Queensland during the Early Cretaceous. However, some other unfortunate dinosaurs have also been found in the same Allaru Formation. These include the titanosaur Austrosaurus and the iguanodontian Muttaburrasaurus.

#my art#SaritaDrawsPalaeo#Kunbarrasaurus ieversi#Kunbarrasaurus#Parankylosaurian#Parankylosaur#ankylosaurs#ankylosaurians#thyreophorans#ornithischians#dinosaurs#archosaurs#archosauromorphs#reptiles#Archovember#Archovember2023

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Archovember Day 1 - Your Choice!

In my ongoing effort to draw all the non-avian dinosaurs we know the colors of, I’ve chosen Anchiornis huxleyi!

The type species for the Anchiornithids (“near birds”), Anchiornis huxleyi was a crow-sized dinosaur living in the Late Jurassic of Liaoning, China. It was relatively common, as hundreds of specimens have been uncovered in this area. But what makes Anchiornis so unique and important is that it was the first Mesozoic dinosaur species to have its entire life appearance be known by man! Having hundreds of well-preserved fossils available allows us to extract a lot of information about not only its size and shape, but its skin, feathers, and even coloration. Anchiornis had long wing feathers on its arms and legs (though its leg feathers were not as long as those of Microraptorians), fluffy downy feathers all over its body, a feathered crest on its head, and feathers covering its feet.

Only two Anchiornis fossils have had their well-preserved melanosomes studied so far. By comparing the structure of these melanosomes to modern birds, paleontologists have been able to infer the life colors of Anchiornis! It had mostly gray and black body feathers and white forewing and hindwing feathers with black tips. Its tail colors remain unknown. The first specimen of Anchiornis to be surveyed for melanosomes also had red or rufous coloring on its crest, as well as rufous speckles on its otherwise black and gray head. However, the second specimen did not have any rufous coloration. This may be due to different preservation of melanosomes, different investigative techniques, the animals in question having regional differences or even being different species/subspecies, the second Anchiornis being younger, or sexual dimorphism.

While Anchiornis had rather large feathered forelimbs, it didn’t seem to have been much of a flier. Unlike the later Microraptorians, its wings were rounded and relatively short compared to other flying dinosaurs, and the flimsy flight feathers overlapped each other to strengthen them. A 2016 study concluded that while juvenile Anchiornis may have been able to use their wings to assist with leaping through the trees, adults were simply too heavy and their wings too small to gain any lift. Instead, it is more likely their wings were used for display. As their legs were long, they may have been adapted for speed, using their wings to aid in aerodynamics as they quickly darted through the underbrush.

Pellets (such as those coughed up by owls) have been found both within and in association with Anchiornis, and contained lizard bones and fish scales. Prey items that could have also been eaten by Anchiornis include insects, arachnids, salamanders, small anurognathids (such as Cascocauda, who we will be visiting later this month) and other small or juvenile pterosaurs, and small cynodonts like Agilodocodon and Juramaia.

Anchiornis lived alongside other Anchiornithids such as Aurornis, Caihong, Eosinopteryx, Pedopenna, Serikornis, Xiaotingia, as well as the Scansoriopterygids Yi, Scansoriopteryx, and Epidexipteryx. It also lived alongside the quilled heterodontosaurid Tianyulong.

#my art#SaritaDrawsPalaeo#Anchiornis huxleyi#Anchiornis#Anchiornithid#paravian#theropods#saurischians#dinosaurs#archosaurs#archosauromorphs#Archovember#Archovember2023

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Archovember Day 18 - Cascocauda rong

The Anurognathids of the Jurassic and Cretaceous were highly derived pterosaurs that filled a similar niche to bats. They were nocturnal or crepuscular, insectivorous (though some larger species may have eaten fish as well), arboreal, and had short tails. However, Cascocauda rong of Middle - Late Jurassic China was an exception to the short tail rule. It’s tail was longer than other known anurognathids, earning it a name meaning “fluffy ancient tail.” But more importantly, Cascocauda provides us evidence of the complexity of pycnofibers in pterosaurs. Long thought to be simple and furlike, pterosaur pycnofibers were thought to be unique structures that evolved independently from feathers. However, Cascocauda had an array of different pycnofiber shapes and structures, one of them being similar to downy feathers with frayed ends. This further strengthens the hypothesis that feathers evolved before dinosaurs and pterosaurs even split into two different clades. Also, infrared spectral analysis was used on these pycnofibers, showing they had a similar absorption spectra to red human hair, making Cascocauda one of the only pterosaurs for which we know its coloration!

Found in the Tiaojishan Formation, Cascocauda rong would have lived with other anurognathids like Jeholopterus, Sinomacrops, and the tiny Luopterus. A wealth of other types of pterosaurs existed here as well, such as Darwinopterus, Kunpengopterus, Archaeoistiodactylus, Pterorhynchus, Wukongopterus, Daohugoupterus, Douzhanopterus, Fenghuangopterus, Jianchangnathus, Jianchangopterus, Qinglongopterus, and Liaodactylus. Dinosaurs lived here too, including the famously colored Anchiornis and other Anchiornithids like Aurornis, Caihong, Eosinopteryx, Pedopenna, Serikornis, and Xiaotingia, as well as the bizarrely bat-winged Scansoriopterygids Epidexipteryx, Scansoriopteryx, and Yi, and the quilled heterodontosaur Tianyulong. Arboreal cynodonts like Agilodocodon, Juramaia, Maiopatagium, Arboroharamiya, Volaticotherium, Vilevolodon, and Xianshou would have shared the trees with Cascocauda rong, adding to the busy, fluffy, feathery nature of this ancient forest.

#my art#SaritaDrawsPalaeo#Cascocauda rong#Cascocauda#anurognathids#pterosaurs#archosaurs#archosauromorphs#reptiles#Archovember#Archovember2023

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Archovember Day 30 - Scutellosaurus lawleri

For our final archosaur, we head to Arizona, USA during the Early Jurassic. Scutellosaurus lawleri was a basal thyreophoran, part of the group which would lead to stegosaurs, nodosaurs, parankylosaurs, and eventually ankylosaurs. But in the Early Jurassic, thyreophorans were small and lightly built, a far cry from the lumbering tanks they would someday become. Scutellosaurus was mostly bipedal, using its long tail as a counterbalance. It had several hundred osteoderms covering its whole body and forming parallel rows, some flat and some pitted.

As more than 70 specimens are known, Scutellosaurus lawleri was probably a fairly common animal. It has been found all over the Kayenta Formation. Its excess of osteoderms was likely due to the amount of predators here. It would have had to look out for the theropods Coelophysis, Kayentavenator, and the apex predator Dilophosaurus. It also lived alongside other herbivorous dinosaurs like the sauropodomorph Sarahsaurus. Early pterosaurs, like the dimorphodontid Rhamphinion, and pseudosuchians like Kayentasuchus also lived here, as well as a variety of early frogs, salamanders, rhynchocephalians, and small synapsids. This environment was an ever changing floodplain, experiencing rainy summers and dry winters at the edge of a large desert.

#my art#SaritaDrawsPalaeo#Scutellosaurus lawleri#Scutellosaurus#thyreophorans#ornithischians#dinosaurs#archosaurs#archosauromorphs#reptiles#Archovember#Archovember2023

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

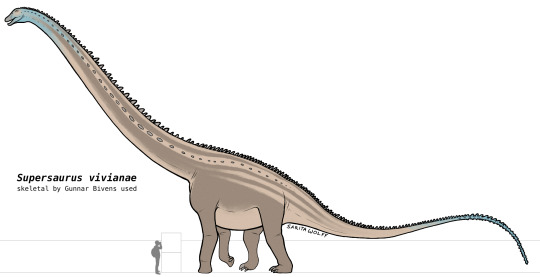

#Archovember Day 7 - Supersaurus vivianae

Living in Late Jurassic North America, the diplodocid Supersaurus vivianae was one of the largest and longest sauropods to ever exist. With larger specimens reaching 33–35 metres (108–115 ft) long and weighing an estimated 35–40 metric tons (39–44 short tons), it was matched only by the Late Cretaceous titanosaur Argentinosaurus.

As a diplodocid, Supersaurus would have used it’s long, peg-like teeth to strip food from branches and swallow it without chewing, instead relying on gastroliths (small stones) to break down plant material in its gizzard. Due to the high stress stripping branches would place on its teeth, diplodocids continuously replaced their teeth throughout their lives, usually in less than 35 days! Supersaurus could have had as many as 5 teeth developing per tooth socket.

Supersaurus, like other diplodocids, had a long, whiplike tail which tapered at the end. They could have snapped this tail like a bullwhip, generating a sonic boom. This could have been used in mating displays or to ward off predators.

Being the largest animals living at the time, there weren’t many, if any, predators in the Morrison Formation that could have preyed on adult Supersauruses. However, young Supersauruses would have had a multitude of large theropods to look out for, including Allosaurus, Saurophaganax, Ceratosaurus, Torvosaurus, and Marshosaurus. Supersaurus would have lived alongside a variety of other sauropods such as Haplocanthosaurus, Smitanosaurus, Amphicoelias, Apatosaurus, Brontosaurus, Diplodocus, Brachiosaurus, Camarasaurus, Dystrophaeus, and the rare Barosaurus. There were a lot of Ornithischians in this formation as well, though not as numerous and diverse as the sauropods. They included the early ornithopods Camptosaurus, Dryosaurus, Nanosaurus, and Uteodon, the stegosaurians Alcovasaurus, Hesperosaurus, and Stegosaurus, the ankylosaurians Gargoyleosaurus and Mymoorapelta, and the heterodontosaur Fruitadens.

#my art#SaritaDrawsPalaeo#Supersaurus#Supersaurus vivianae#diplodocid#sauropods#saurischians#dinosaurs#archosaurs#archosauromorphs#reptiles#Archovember#Archovember2023

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

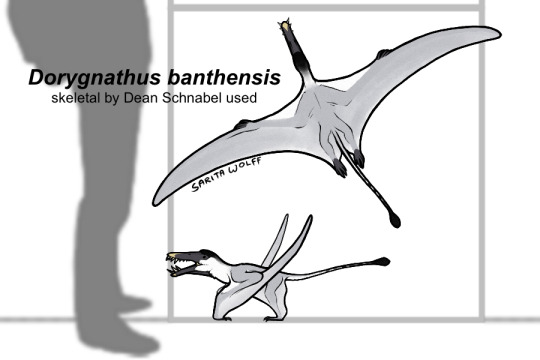

#Archovember Day 13 - Dorygnathus banthensis

Dorygnathus banthensis was a rhamphorhynchid that lived in the Early Jurassic of Europe, also in the time of the early Tethys Sea taking up most of the continent. (I did not realize I had put so many of these Jurassic archosaurs this close together when I made this list! We’ll be getting something from the Cretaceous tomorrow, don’t worry.) Like other rhamphorhynchids, it had a short neck, a long tail, and large interlocking fangs for catching and gripping wriggling fish. Wear on the teeth of some specimens suggest that they may have also fed on hard-shelled prey like mollusks and crustaceans. One specimen also contains preserved hairs, further evidence of pycnofibers or feathers in all pterosaurs.

Dorygnathus was more common in its environment than its contemporary Campylognathoides, and both have been found in marine deposits suggesting they regularly traveled over open sea. Dorygnathus would have lived alongside our previously visited Macrospondylus bollensis as well as other teleosauroids like Mystriosaurus, Pelagosaurus, and Platysuchus. It would have come across sauropods like Ohmdenosaurus, and flown over the variety of Early Jurassic ocean life like icthyosaurs, small plesiosaurs, early sharks, ammonites, and much more.

#my art#SaritaDrawsPalaeo#Dorygnathus banthensis#Dorygnathus#Rhamphorhynchid#pterosaurs#archosaurs#archosauromorphs#Archovember#Archovember2023

21 notes

·

View notes