#Seto has that sort of mindset of like

Text

I always make jokes about Yugi getting revenge for the exodia cards but like,,did anyone ever tell Seto what happened to them? Would he care? Yugi mentions it in passing to him once and later on Weevil wakes up at 3 am to see a tall figure outside his bedroom window, frothing at the mouth, going “Into the ocean?? I’ll send you into the ocean”

#I’d like to think that as his rival#Seto has that sort of mindset of like#wait you can’t do that that’s my job#how’s he supposed to use his strategy to beat exodia now??#you just know after that he wanted a rematch to prove he could somehow win against exodia but whoops! they’re hanging out with the fishies#hgghhh Seto ‘I made it to the afterlife I can find some cards in the ocean’ kaiba learning how to build submarines#I hope this makes you laugh ha-tep!#yu gi oh#yugioh#seto kaiba#yugi mutoh#yugi moto#yugi mutou#weevil underwood#insector haga#I don’t know but I am still SO BITTER about exodia

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Request: Yandere Pharaoh Atem x reader, Yandere Yugi Muto x reader, and Yander Yami Yugi x reader when would they force their sexual advances on their darling and how they would they react to their darling escaping and never seeing them again.

~I tried to make this gn as possible but Atem wasn't easy :/~

WARNING: THIS FICTION CONTAINS SEXUAL THEMES IF YOU ARE UNCOMFORTABLE WITH THAT PLEASE LEAVE NOW.

~Pharaoh Atem:

Atem isn't sexually driven. Don't get him wrong every part of you is like a goddess to him, but you just started coming around to his ways he didn't want to break that.

However when the council starts pushing him to marry someone for an heir he jumps to action.

He will start of with bring this up to you. "They really want my legacy to carry on...but I don't want just anyone to bear my children"

He will wait for reaction, but if you still wont respond is when he starts pushing harder.

At this point his flower isn't two states. 1. They are so numb to everything whatever he says they will agree to or 2. With all their might they will fight with all their might. Neither matter to him however.

No matter your state of mind he will then tie you to the bed, and begin the long process of breeding you till you pregnant with his child.

Once you its confirmed by a trusted physician that you are indeed pregnant with the Pharaoh's child he will then start making wedding plans, to make you his true queen.

What the poor lovesick Yandere didn't account for was an attack on the palace during the wedding by the Theif King himself.

During the attack you would be locked in his bedroom hearing the discord on the other side. You place and hand on your stomachs wondering if you should really leave.

The decision was made for you when the Theif King barged in himself. Wicked grin plastered on his as he ripped you from the bed and into the main chamber.

When Atem sees you in Bakura's grasp he feels his blood run cold l, he tries to reach you but Bakura's minions blocked his path.

The last thing he saw was you on the back of Bakura's horse. "If you ever want to see your little play thing again Pharaoh then I would advise you bringing me the mallinum items."

He wanted to stop Bakura, he wanted to stop him from taking his child and lover, but he didn't make it in time.

Stories say the Pharaoh never found his flower and in final years he became erratic, angry at everything and everyone. He even went as far as to kill anyone who displeased him. He never gave up his search for his flower and child, but the fruits of his labor were never reaped.

~Yugi Muto

Yugi always had a sexual attraction to you, as well as mental attraction. He didn't act on this until he knew it was the right time.

It was a slow process at first. Getting you use to your new home enviroment, showing you that no one would love you but him.

When you started coming around even going as far as calling him your boyfriend, he was ecstatic.

His will begin to roam more, until eventually he will pin to your mattress with a lustful look in his eyes.

"I want to show you how much I love you Angel"

Something in you screams to not let him do things to you and your body, but your mindset was fixed on that he was boyfriend and you trusted him that you couldn't fight back.

His little fantasy didn't last long I'm afraid. When he was gone fighting another duell his grandfather went to the basement to store extra packs of cards he received when he found you.

Mr. Muto remembered seeing you all over the news and panicked slightly. Could his sweet grandchild Yugi really do this? Why? What purpose?

When you woke calling for Yugi, Mr. Muto knew couldn't leave you like this but he could let Yugi go to jail either...he was his own family left.

Against Mr.Muto's better judgment he took your near collapsed form and took you to the police, he explained to them that you were found near his gameshop, but he didn't know where you came from.You were then taken to the hospital, put under extreme care.

When yugi found out her panicked and furious. How did this all come to be? He thought he was being cautious.

He tried to get into your room but was told only family was aloud to visit you, this made him angrier. Didn't they know he was everything to you?! Didn't you tell them?!

No matter how hard he fought they wouldn't allow him in. So he had to sit in wait. When you were released he tried to get in contact with you but all leads led him nowhere.

He continued to look for you any sign would do, but he always came up empty. Over time he secluded himself from his friends and family slowly going crazy. He used his title "King of games" to find you, but he never did. The kidnapping of you lived and died with Yugi Muto.

~Yami Yugi

The more time he spent with you the more his feelings began to grow. He eventually dreamed of having children with you.

Yami knew you needed more time before he pushed that sort of thing on you, but he was starting to get impatient. You knew he loved you right? And he loved you. So why cant this love create a beautiful life together?!

When first tried he was face with heavy resistance and your part, so he had to punishments in order to remind you of your place.

When he tried a second time he tried will less force and more compassion.

"My beloved I only wish for lives to be intertwined like our hearts already are."

Still bruised and weak from his last try you reluctantly agree. When you did he was ecstatic. He would finally have the family he dreamed of 5,000 years ago, and this time no one will stop him.

Or so he believed time has a funny way of repeating itself, but this time the beginning of his end started with Seto Kiba.

Seto came to Yami's demanding a duel not knowing Yami wasnt home. So when Seto came across the room with you in it he didn't know what to think. This wasn't Yami's doing right?

When you woke seeing Seto in front of you, you scrambled to him or at least as far as the chains allowed. You begged for his help wanting out of this hell.

Kiba knew he should have taken you to the police you were the missing person that seemed to disappear with a trace, but he didnt want yami to be thrown in jail. That's not how he wanted to get the title of the best duelist.

So instead he offered to set you free on three conditions. You would eevee talk about this experience with anyone, you will allow him to not only change your identity, but he would move you out of Japan and to some where far far away from here. Not seeing any other way out you agreed.

When yami was on his way home he saw you get into kiba's limo. Fear, and adrenalin pulsed through his veins. He tried to catch up to car but he wasn't fast enough.

He tried to get Seto to tell him the details of your disappearance, but kiba stayed silent knowing this what was best for both duelists.

Yami felt defeated he grew angry, and craized. He attacked anyone he felt was holding out information on your whereabouts effectively sending them to the shadow realm. He never did find you, but on his death bed he swore that he will find you one way or another. You two were fated to be together afterall.

💕Requests are open 💕

130 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hc that Ardbert’s soul and Vaste’s are like Lews Therin Telamon & Rand al’ Thor if the distinction between them was clearer and the other WoDs were smaller pieces of their souls too in their destiny to become WoLs initially (also after ShB they aren’t voices in her head but it is easier for her to perceive their spirits on The First, or in high aether places; within the realm of the Lifestream itself she can merely think of them for them to appear)- if Vaste interacts with people on The First who can remember those heroes/heard enough about their real selves, then they can distinctly feel some aspect of her at moments that resembles Them as by being a WoL she sort of does inherit parts of Them even without realizing, in a more tangible separate way than simply accepting their legacy, they are truly one and the same at the core no matter their personalities

Tbh I feel like Fae in this regard would be able to tell/figure out she both is and isn’t their old friends, they might even accidentally call her by one of their names/titles, or be able to see shimmers of their now freed spirits if for instants that feel like hallucinations (kinda like what Seto felt but it manifests and bleeds literally into some of her actions and the shape of her soul)

100% too when she had to put down each of the Cardinal Virtues she cried every time and even let them hit her/dodged around and around not attacking/yelled at them/tried comforting them, because she desperately wanted to believe the idea that They were still in those bodies somehow, and when they aren’t every time it breaks her its worse than death, to see wasted life

I like to think its one of the major moments that make her shift toward the pacifist mindset and realizing how pointless all the killing in her life has felt, how tired she is and ashamed of it, it wars against what shes gotten used to and her anger/pain at being the others tool and dehumanized

Also on the side letting this sit in my head for weeks has made me want an alternate version of killing Emet where like, you use ALL of the WoDs weapons in the same order of sequence + abilities you see their lookalikes use during the End of An Era cinematic @ 2:00 (and Ardbert’s weapon last after their shades let you use themselves to boost or just through momentum you jump in the air to cleave the axe down)

#i havent slept in weeks whats good this is my high fantasy bullshit now#hc#the soul is many; the heart is one

1 note

·

View note

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 3 (18.8): Two Arrangements for a Karamono-chaire and a Dai-temmoku on the Fukuro-dana.

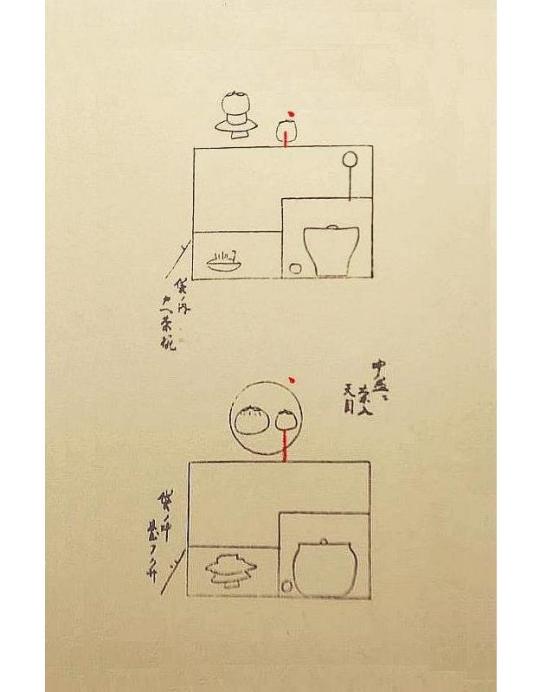

18.8) Two arrangements for a karamono-chaire¹ and a dai-temmoku² on the fukuro-dana.

[The writing reads: (to the left of the upper sketch) fukuro no uchi kae-chawan³ (袋ノ内 カヘ茶碗); (above the lower sketch⁴) naka-bon⁵ ni chaire ・ temmoku (中盆ニ 茶入・天目), (to the left of the lower sketch) fukuro no uchi dai⁶ ・ fukusa⁷ (袋ノ中 臺・フクサ).]

_________________________

¹These are “ordinary” karamono-chaire*, pieces that do not merit mine-suri [峰摺り] placement. As such, while resting on their kane, they are placed very slightly off center -- this is what the pictorial orientation is intended to suggest.

___________

*According to his densho of 1582 or 1583 (the surviving manuscript is undated, but it must postdate the creation of the tsuri-dana [釣棚] during the summer of 1582), Rikyū would probably have included the old Seto chaire -- the pieces made under the direction of the chajin arriving in Japan from the continent during the fifteenth century -- in this proposal.

²While the temmoku was most likely also an imported piece (though the rare Japanese-made temmoku were often technically identical, and generally handled in the same manner -- frequently not being distinguished from the imported pieces*), the chawan was felt to be intrinsically inferior to the chaire†, hence its usual arrangement in a slightly inferior manner.

___________

*Rikyū’s ake-temmoku [赤天目] (shown below) is a good example.

While it is unclear what he actually believed regarding its antecedents, he handled it and used it in the same way as a karamono-temmoku.

Furthermore, in the Yamanoue Sōji Ki [山上宗二記], the white temmoku (which were made for Jōō at the Seto kiln) are ranked highest, above all of the imported bowls. This suggests that, rather than simply being a manifestation of the mindset that favored continental pieces over local wares, the preference for imported chaire was due to their technical superiority to the pieces that were being made by the local potters. (Of course, this attitude underwent a change in the Edo period, when imported pieces were valued simply because they were imported.)

†While a chaire was felt to improve with repeated use (as the aromatic elements in the matcha work their way into the clay), chawan were originally used only until they began to exhibit signs of “contamination” -- for example, the crackles in the glaze becoming stained with tea -- and then replaced. The lack of crackles in the glaze on the Chinese temmoku may have been the reason why they stayed in use much longer than others.

While this idea started to weaken once chawan began to be recognized as meibutsu objects that were deserving of preservation -- which attitude was reinforced by Jōō’s own approach of amassing a large collection of such pieces -- their inferior status vis-à-vis the chaire continued to be a feature of chanoyu in Jōō’s day (as it remains today).

³Kae-chawan [カヘ茶碗].

The term kae-chawan [替茶碗] refers to a “substitute chawan” used to bring the chakin and chasen (and sometimes the chashaku, as in this case) into the room at the beginning of the temae, and which was used to clean the chasen at the end of the temae, using cold water (in order to protect the temmoku from being soiled by this process). It was not (necessarily) used to serve tea -- though this idea was being questioned more and more by the chajin of Jōō’s period (when the kae-chawan was often being used to serve usucha -- a practice that enhanced the temmoku’s status).⁴

⁴There is a critical issue -- apparently a copying error -- with this illustration, as it appears in the Enkaku-ji manuscript of the Nampō Roku. In Tachibana Jitsuzan’s original sketch (which is the version that has been reproduced here) -- the sketch he made with the Shū-un-an documents spread out in front of him* -- a futaoki is shown on the lower shelf, next to the mizusashi. Jitsuzan, however, apparently neglected to include the futaoki in the sketch that was prepared for the Enkaku-ji manuscript†. The futaoki, then, is absent from all of the sketches that were later based on the Enkaku-ji manuscript.

This is extremely important, since the presence (or absence) of the futaoki impacts on the kane-wari interpretation of the arrangement -- and its absence here has resulted in very confusing speculations (by certain commentators) regarding the way that the utensils arranged on the tray should be counted‡.

It would have been very easy to remove the futaoki from the sketch digitally, and so make it more closely resemble that in the Enkaku-ji version of this document. But since its absence there is obviously a mistake (without the futaoki it becomes impossible to rationalize the kane-wari for the goza), I felt it was best to leave the futaoki in the sketch, even though that means that I am no longer showing a likeness of what is found in the Enkaku-ji manuscript (which is the teihon [底本] on which this translation is supposed to be based).

___________

*We must assume that, regardless of the temporal constraints under which Jitsuzan was working (as has been mentioned before, he was only given access to the Shū-un-an documents for a limited period of time), the original sketches that he made with the Shū-un-an documents spread out in front of him necessarily would have had to closely resemble the documents that he was copying, especially in details such as this (otherwise he would surely have edited them on the spot -- since his purpose was to make a copy of the originals for his own reference and study: the idea of proselytizing the resulting material does not seem to have occurred to him until later). Thus, the accuracy of the first manuscript must take precedence over the copy that he made several years later. (Jitsuzan seems to have requested accessed the original documents in 1586, after examining a copy of the Rikyū Chanoyu Sho [利休茶湯書], while on his way from Kyūshū to Edo in observation of the sankin-kōtai [參勤交代], or “alternate attendance,” rule; meanwhile, the presentation copy for the Enkaku-ji was prepared between 1689 and 1690. The Rikyū Chanoyu Sho [利休茶湯書] was translated, in its entirety, previously in this blog.)

†A futaoki is not displayed on the ji-ita in several of the subsequent arrangements -- because it is placed somewhere else (or its absence plays into the correct count, so far as kane-wari is concerned). It seems that Jitsuzan may have looked ahead to the next page of sketches, and so overlooked its presence in this sketch.

‡The objects arranged on the tray are all counted as a single unit, since the tray itself contacts all of the kane with which those utensils are associated individually. Nevertheless, with the futaoki absent, this has lead some interpreters to argue that the objects arranged on the ten-ita should be counted as if the tray were not present at all. The result is a lingering confusion that taints their understanding of the rest of the Nampō Roku.

⁵Naka-bon [中盆].

As in the previous post, this is usually taken as a reference to the (meibutsu) naka-maru-bon [中丸盆], which measures 1-shaku 2-sun 3-bu in diameter.

There was, as Shibayama Fugen points out, also a hō-bon [方盆]* version (which measured 1-shaku square).

Round trays, however, were considered less formal -- making them more appropriate to the setting. Regardless of which tray was used, the fukuro-dana would still have been placed 1-shaku 2-sun away from the upper corner of the ro.

___________

*Hō-bon [方盆] means a square (or sometimes rectangular) tray. The word shi-hō-bon [四方盆], literally meaning a “square tray,” does not seem to have been used that commonly in Jōō’s period.

The 1-shaku square tray was not one of the Higashiyama gomotsu [東山御物] that were used by Ashikaga Yoshimasa, as was the naka-maru-bon; the square tray was first introduced by the early machi-shū practitioners, the mostly immigrant-chajin of Shukō’s generation.

The square naka-bon will appear in the next post.

⁶Dai [臺].

The temmoku-dai [天目臺].

In Jōō’s period (and before) these were either plain black-lacquered dai that had been imported from the continent* (a typical example is shown below), or (much less frequently) Japanese-made copies.

The reason the dai is placed in the ji-fukuro has nothing to do with its quality or antecedents. Rather, it is because the naka-maru-bon is the largest tray that could be used with the fukuro-dana†, and this tray is not sufficiently large to allow the temmoku to be displayed on its dai together with the chaire.

___________

*In China, these dai were used to hold the conical bowls in which heated sake was served in restaurant and drinking establishments (this is why many of them were painted with the marks of the houses from which they came -- so that they could be claimed by their rightful owners later: the Chinese, then, as now, delighted in having meals catered, and since this often involved different things being sent from several establishments, correctly sorting the dishes afterward became an issue) -- the sake was usually flavored with medicinal herbs, and the conical shape allowed the dregs to settle to the bottom, so they would not discommode the drinker. While quite commonplace objects on the continent, these dai became great treasures in Japan -- an almost worshipful attitude that was certainly helped by the trade embargo that followed the overthrow of the Koryeo dynasty (in the first years of the fifteenth century), and the establishment of the Josen tributary state (in the middle of the fifteenth century) under a Ming hegemony.

†The meibutsu nagabon that were typically used with the daisu when the host wished to display both the chawan and the chaire on a tray were not used with the fukuro-dana, since Jōō felt that these trays were too formal for the setting. Jōō selected the most informal arrangements for the daisu and elevated them to the highest rank in this new setting.

⁷Fukusa [フクサ].

This would be the host‘s temae-fukusa. While there were different ways it could be placed on the dai (the purpose being to cover the hole into which the foot of the chawan would fit), the simplest way was to fold the fukusa into quarters and rest it on top of the dai (with the corner that the host would need to grasp, to lift the cloth up and fold it, on the right), as shown in my sketch (below).

While I have colored the fukusa purple (and made it the size of a modern-day fukusa so that the hane of the dai will be visible -- these sketches are always carefully drawn to scale), for clarity, this is an anachronism. In Jōō’s period, the host’s temae-fukusa was always made of imported donsu, usually in a color scheme favored by the host (or, perhaps, his economics -- since the fukusa was used only once and then discarded, and cloth woven in unpopular colors was naturally cheaper), and they were generally slightly over 1-shaku square (meaning that the hane of the temmoku-dai would probably not peak out from underneath the fukusa, even by a little).

The first purple “fukusa” measuring 8-sun by 8-sun 2-bu were originally not made to be fukusa, but as small furoshiki (wrapping cloths)* in which lacquered containers of matcha were tied before being enclosed in a sa-tsū-bako [茶通箱] (for presentation as a gift to someone). The first time this kind of cloth was used as a temae-fukusa was on an occasion when Furuta Sōshitsu received a sa-tsū-bako of tea from Hideyoshi (forwarded to him by Rikyū, probably so that its arrival would coincide with the gathering). Since Oribe was already in the tearoom when the gift tea arrived, and had apparently not been expecting it, he had not prepared a second fukusa (the host’s futokoro is usually stuffed with so many things that a random fukusa would easily get lost, especially when the host was not expecting to use it, so Sōshitsu can hardly be blamed). Nevertheless, wishing to share the gift tea with his guests, he decided to use the furoshiki in which the natsume was tied as a fukusa when serving the tea in the sa-tsū-bako (a new fukusa had to be used with each new kind of tea, to prevent contamination). Rikyū was informed of this, and not only approved, but began to imitate the practice during his own chakai.

Oribe is the one who began to make his own fukusa of purple-dyed Japanese cloth† (and of the same size as these furoshiki, since he found that a fukusa 8-sun by 8-sun 2-bu was actually easier to handle than one made from a larger piece of cloth), and this idea caught on among the machi-shū in the years after Rikyū’s death (when they looked to Oribe for an explanation of the chanoyu of Jōō’s middle period as part of the effort to repudiate Rikyū’s influence on chanoyu†).

___________

*The practice seems to have been established by Jōō (though probably based on even earlier traditions). With imported cloth rare and costly, and since the furoshiki in which the container of gift tea was tied was used only once (and would not be seen by the guests -- immediately after removal it was tied in a knot and put into the host’s left sleeve), the best-quality native cloth available was used. Dark purple (it is almost black -- a deep brown-purple shade) was the most difficult color to achieve using natural dyes, hence it is the color that was preferred by Jōō for this purpose.

†Red fukusa arose from a very different (and confused) route. When Sōtan was called upon to serve tea to the court of Tōfukumon-in [東福門院; 1607 ~ 1678] (Tokugawa Masako [徳川和子], granddaughter of Ieyasu, and the consort of the retired emperor Go-mizu-no-o [後水尾天皇; 1596 ~ 1680]), he was distressed to find that the women’s lipstick stained the chakin like blood. Therefore Sōtan had his chakin dyed scarlet, to hide the stains. Later generations, hearing about the dying of the “tea cloth” red from the dyers, but lacking access to the details (the word chakin [茶巾] was sometimes used as an alternate name for the fukusa), people began to assume that the thing that was dyed red for the women was the temae-fukusa. Since this dichotomy fit into the Tokugawa’s neo-Confucian segregation of the sexes, women using a red fukusa became standard practice.

†Sōshitsu, who was 11 years old at the time, was introduced to Jōō shortly before the latter’s death. It is said that Jōō (who was no longer teaching at that time -- as was the convention of the day, where the actual teaching was done by the senior disciples gathered around the master) is the one who introduced Oribe to Rikyū, and advised him to seek instruction with this favored disciple (perhaps sensing some sort of fellowship of the spirit would arise between the two -- and, of course, pointing him in the direction of Jōō’s other main disciple, Uesugi Kenshin, would have been a disservice, since Kenshin was antagonistic to the direction that the government was taking, and association with him could have lead to the young man’s ruin). Nevertheless, the myth that Furuta Sōshitsu had studied with Jōō arose among the machi-shū after Rikyū’s seppuku (perhaps the rumor was started by Imai Sōkyū), and so it was to him that the group of which Shōan and Sōtan were members looked for guidance in those troubled times.

Oribe seems to have studiously answered their questions (only), while offering nothing about which his interlocutors were too ignorant to ask (the transcripts of these interactions are truly startling -- the depth of minute detail in Sōshitsu’s knowledge is absolutely breathtaking), and so carefully protected Rikyū’s legacy from being usurped by his antagonists. The result, unfortunately, is that most of what we associate with Rikyū was actually done by Jōō or Sōshitsu, while most of Rikyū’s true teachings went with Oribe to his grave (only to be rediscovered in the 20th century when Rikyū’s densho began to come to light).

==============================================

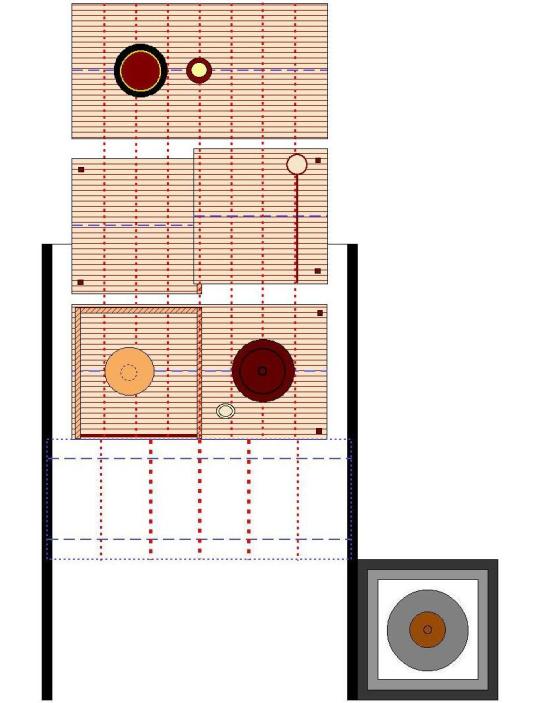

I. The first arrangement.

This first arrangement shows what might be considered the basic way in which a karamono-chaire and a dai-temmoku might be arranged together on the fukuro-dana. The chaire is placed on its kane (though not as a mine-suri [峰摺り])*, while the temmoku “overlaps” its kane by one-third (in other words, the foot of the temmoku -- not that of the dai -- is located immediately to the right of its kane). This results in a separation between the chaire and the hane of the dai of 2-sun.

The hishaku is associated with the right-most kane on the naka-dana, while the kō-dana has been left empty. And the mizusashi and futaoki have been arranged together in their compartment on the ji-ita, as usual.

While the kae-chawan† has been placed in the ji-fukuro, it is not included in the kane-wari count, meaning that the tana holds five units, and so is han [半].

___________

*The ku-den elucidates this matter -- that, because this is a karamono-chaire (albeit not one of the very highest rank), it rests on the kane, though not as a mine-suri.

†Both the Shukō-chawan and the ido-chawan were used as kae-chawan in the early days, and an ido-chawan was most likely the kae-chawan on this kind of occasion.

The reason why a chawan of a different size was traditionally preferred as the kae-chawan is because, since this chawan has only a supporting role in the temae (aside from bringing out and removing the chakin and chasen at the beginning and end of the service of tea, its only other participation in the temae was to give the host a place to clean the chasen with cold water at the end of the temae), a second chakin is not necessary -- because, while the chakin is folded first in thirds when prepared for a temmoku (or other small bowl -- including things like the raku chawan), it is folded first in half when it will be used to dry a large chawan. Thus, even without a new chakin, a clean surface is presented for use simply through the act of refolding the chakin. This is not possible if the two chawan are of the same size (and in such a case -- according to the Nampō Roku -- two different chakin would have to be used, folded together rather as if they were a single chakin of double the usual width: the so-called “shin chakin” [眞茶巾] used by some schools in their higher temae replicates this idea, which seems to have been the inspiration, though apparently the ancients considered that using separate chakin, rather than one of double length, was “necessary” to completely separate the effects of wiping the first bowl from contaminating the second).

——————————————–———-—————————————————

II. The second arrangement.

Here the temmoku and karamono-chaire are arranged together more formally, by being placed together on a naka-bon. Though the sketch is a little confusing, the intention of the red line is to show that the chaire is resting on its kane, albeit not as a mine-suri [峰摺り]*. Meanwhile the temmoku (which is placed on the tray tied in its shifuku, but without its dai) is arranged so that it “overlaps its kane by one-third” (the foot of the temmoku is immediately to the right of the kane with which it is associated), resulting in a separation of 2-sun between the chawan and the chaire†.

Both the naka-dana and kō-dana are left empty‡, while the futaoki is placed next to the mizusashi, as usual.

Looking at the kane-wari, the tana here has a han [半] value, which is appropriate to the goza of a gathering held during the daytime**.

___________

*This appears to be the purport of the ku-den, according to the commentators.

†When the temmoku is 4-sun in diameter, and the chaire is a 2-sun 5-bu katatsuki (or other shape with the same diameter -- many of the kansaku karamono chaire [韓作唐物茶入] were made this size, while being shaped like the famous Chinese ko-tsubo [小壺]).

4-sun, and 4-sun 9-bu, are the standard sizes of chawan that match Jōō‘s system of seven kane. (The Shukō-chawan, with a diameter of 5-sun 2-bu, was too large to display in this setting, other than as a mine-suri.)

‡This naka-bon kazari [中盆飾], to use its formal name, was derived directly from one of the original daisu arrangements, and the daisu, of course, does not have these tana present between the ten-ita and the ji-ita. Thus, to leave them empty, is not a problem.

**For purposes of kane-wari, the empty tana are counted as chō [調]. Therefore, han (the ten-ita, which has a single unit arranged on it) + chō (the empty naka-dana) + chō (the empty kō-dana) + chō (the mizusashi and futaoki on the ji-ita count as two units because they contact different kane) gives a total of han.

1 note

·

View note

Note

Can you HC firsts with Seto? First kiss, first time holding hands, first time having diddly do, first time going into labor... Cute shit

Here you are nons~~

xxxx

First kiss: Seto would be more nervous than he would ever admit in my opinion. He ha spent most of his life pushing away any kind of emotional attachment other than Mokuba and let’s face it, Kaiba isn’t even extremely emotional towards Mokuba. He has those emotions, of course, but he keeps a reign on them but Mokuba has been around him long enough to understand him and doesn’t ask for more. Seto is the KING of trust issues and he definitely keeps everyone at more than arms length. It would be hard for any lady (or gentleman) to get close to him or even get this first date because of how untrusting Seto is. He is of the mindset that you can only rely on yourself. If there was a quick first date, it would hardly be called a date and would rather be a meeting because he likely wants something from that person. Once the date actually happens, he would be so nervous (and hiding it very well of course) because it will have been the first time that Kaiba could ever remember that he would find himself caring about someone else that was not his brother.

First time holding hands: I’m going to be honest, I don’t think it would be in public. Kaiba does not at all strike me as the type to have public displays of affection...not unless it was a political maneuver because let’s be honest when you run a major company that has to compete for revenue and power over other reputable businesses or try to gain connections and favors, politics are going to be involved. So odds are, any political maneuver that involved public displays of affections would be with someone he didn’t actually care about. So, that being said, the first time he held his partner’s hand...would probably be when he wasn’t paying attention. Like him reading a book or reading paperwork while sitting next to his partner and his hand drifts towards there’s unconsciously, seeking their warmth.

First time having sex: So I do think he has had sex before, especially for those political maneuvers that I mentioned earlier. But this would be the first time that he had sex and it mattered. So he would be nervous too and probably not up to his normal performance (but they don’t have to know that.) I feel like it would take a very long time to successfully sleep with him if he was dating someone because this would be a MAJOR vulnerability and being able to allow any kind of emotional vulnerability, even if he wouldn’t let it show, would require a lot of trust. And like I said, he has major trust issues. I think the first few times it almost happened he would have deflected or magically “realized” that he had some important work to do.

First time his partner goes into labor: He will never admit but he would be an utter wreck inside from worry. So many questions would be rolling like: Can he handle being a father? Is he ready? What if he becomes like his stepfather? What if something happens to his lover? What if something happens to the child? Would Mokuba really be ok with all of this? So due to this anxiety, he’d probably be the sort to remind the staff helping deliver the baby that they had better provide the best or suffer the consequences.

So basically I headcanon Seto Kaiba as a demiromantic who doesn’t develop romantic attraction unless he starts to trust them and that will take forever and a day to earn.

#yugioh#ygo#Seto Kaiba#Seto Kaiba headcanons#demiromantic#Seto is demiromantic#just a few thoughts#Anonymous

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 4 (7): Concerning the Display of an Unnamed Hitsu-dai [筆臺].

7) When a hitsu-dai [筆臺]¹ was displayed in the Higashiyama Palace², if that hitsu-dai was one that lacked a name -- or recognition -- the feeling was that it was best to be reticent³:

- Sōami and his followers taught that [if the hitsu-dai was an ordinary piece], it might be said that one could proceed [but only after carefully thinking the matter through first, weighing the pros for display against the cons];

- Nōami, however, held that excessive reticence is out of place⁴ -- and an ordinary suzuri-bako should also be arranged together [with the other things on the tsuke-shoin] in the same manner⁵.

Naturally, when considering the way to display a meibutsu, one must change the way one is thinking⁶: this good teaching was handed down from Kūkai [空海]⁷ to Dōchin [道陳]⁸, and then to Sōeki [宗易].

_________________________

◎ This entry appears to be at least partially (though, more likely, entirely) spurious. Not only is the language inconsistent with the rest of the book (suggesting, at the very least, that it was incorporated into the material that became Book Four of the Nampō Roku from some other source), but the author appears to lack any real understanding of either Nōami's, or Sōami's, teachings -- or the relationship between the two -- or the actual nature of their writings.

Furthermore, the way it touches on the orthodox line of transmission in the last sentence -- from Nōami to Kūkai, to Dōchin, and then to Rikyū -- would be highly anachronistic in a series of notes that otherwise appear to have been set down rather early in Jōō's career (as is the case with the vast majority of the entries that are included in Book Four of the Nampō Roku).

More will be said on this in the section that has been appended to the end of this post.

¹Hitsu-dai [筆臺].

According to Shibayama Fugen, “the hitsu-dai is one type of suzuri-bako [硯箱]*. A suzuri [硯, ink-stone], a suiteki [水滴, water dropper], hitsu [筆, brushes], and [a stick of] sumi [墨, an ink stick], are laid out together on a hei-pan [平板]†. Beginning in the Higashiyama period, [this hei-pan] was, in turn, placed on top of the [packet of] ryōshi, and so it was displayed [on the dashi-fuzukue].

“With respect to the brushes, there should always be two‡.”

Tanaka Senshō, meanwhile, states that the term hitsu-dai refers to a sort of tray on which the brushes and ink stick (only) are placed**. "The kind of long, rectangular tray used in the present-day as a jiku-bon [軸盆] is what is meant," being his description of the object in his commentary.

The Chinese tray shown above matches his description.

Later on, however (he adds) the suzuri (ink-stone) also came to be placed on the hitsu-dai; and when it was then fitted with a lid, the result was the suzuri-bako (an example of which is shown below -- the box, containing a suzuri and metal suiteki, with a compartment on the right for brushes, and another on the opposite side of the ink-stone for a stick of sumi, is shown below)††.

This entry was also discussed briefly in Kumakura Isao's Nampō Roku wo Yomu [南方録を読む].

__________

*Suzuri-bako [硯箱]

†Hei-pan [平板] refers to something resembling a plate: a flat face with a low, raised rim. A shallow tray is the sort of object being described.

‡In the book of secret teachings that accompanies the Nampō Roku (this document was prepared by the group of scholars who gathered around Tachibana Jitsuzan, in the Enkaku-ji, in the decades after his manuscript was presented to that temple) is found the statement suzuri-bako no uchi fude ni-hon iu-iu [硯箱ノ内筆二本云々]: "within the suzuri-bako, [there should always be] two brushes, so it is said." Shibayama argues that this dictum applies to the hitsu-dai as well.

**The tray would keep the brushes from rolling off the packet of paper, while also protecting the paper from possible ink stains.

As has been mentioned before, the paper displayed on the tsuke-shoin was usually imported from the continent, and both rare and costly.

††This suzuri-bako was made for Ashikaga Yoshimasa. Though unquestionably very beautiful, and of the highest workmanship -- in that period, the finest craftsmen worked expressly for the shōgunate, with things such as the gold powder used in the maki-e on this suzari-bako coming from the shōgun’s own treasury -- as a new piece, such objects would have lacked both a “name” (see footnote 3 -- in the early days the names usually referred to a past owner, thus it would not likely have gained a name until after Yoshimasa’s death, assuming it was an especially treasured piece) and a “reputation” (since this was “bestowed” by the community, and posterity, rather than the owner), and so been precisely the kind of object that is being discussed in this entry.

Consequently, it was never a question of quality, but of the antecedents and accolades that the individual piece had acquired over time.

Na [名], usually translated simply as “name,” means both the literal name, and the object’s (or person’s) reputation.

²Higashiyama-dono [東山殿].

The word refers to the palatial residence of Ashikaga Yoshimasa [足利義政; 1436 ~ 1490]. It was also used as a sort of nickname for Yoshimasa, as the lord of that palace.

Here it could have been used with either sense.

³Na mo naki hitsu-dai nado, enryo aru-beki yoshi [名もなき筆臺など、延慮あるべきよし].

Na [名], as mentioned above (under footnote 1), means both “a name” and “a reputation.” Newly-made pieces, of course, would have lacked both -- even if they were of the highest quality*.

Enryo [延慮 = 遠慮] means modesty, reservation. Even the shōgun might make use of ordinary things in his day to day life -- and since the shoin was his private study, there is no reason why he would have to secret his usual things away, and then replace them with famous antiques, when receiving guests.

The text is not saying that such objects absolutely should not be displayed, but that one should be circumspect, and think things through carefully, before doing so.

___________

*The way of thinking during this period was that, because the object was recently made, it could be easily replaced, and so was inherently expendable. Objects imported from China or Korea, however, could not be replaced -- not only because they were often antiques (and the craftsmen who produced them were no longer alive, or the technologies employed in their creation were no longer being practiced), but on account of the trade embargo with the continent that would not be lifted until the second half of the next century.

Now, we view pieces made by famous makers in much the same way, since they are prohibitively expensive, and so difficult or impossible to replace. But in the period that is being considered here, these craftsmen were effectively retained by the government, and while they may (or may not) have received special compensation or recognition for the exceptional pieces that they created, producing objects of that quality was their job.

This attitude still prevailed during Rikyū’s day, and is why using modern-made pieces was considered wabi -- and why, when the host was planning to serve two different varieties of koicha during the same wabi gathering, Rikyū advised him to prepare two separate chawan (since these modern-made pieces were without value, when compared with the precious antiques). It was only when using an antique that Rikyū sanctioned cleaning the original chawan carefully, and then using it to serve the second kind of koicha.

This all had nothing to do with the host’s personal feelings toward his utensils: Rikyū certainly treasured Furuta Sōshitsu’s black bowl that he named Naga-tabi [長旅], and continued to do so, and use it lovingly, until the end of his life. But because this bowl was newly-made, and Oribe was still very much alive, the chawan was not considered in the same way as Rikyū‘s ake-temmoku [朱天目] (also known as Rikyū’s Seto-temmoku [瀬戸天目]), which, even though apparently produced at the Seto kiln (though it is not clear whether the people of his period knew that), could not be replicated. Thus the ake-temmoku was protected by Hideyoshi after Rikyū’s death, and survives to this day, while Oribe’s black bowl was apparently destroyed along with the rest of Rikyū‘s personal effects, on Hideyoshi’s orders.

⁴Enryo ni oyobazu [延慮に不及].

Oyobazu [不及 = 及ばず] means “not required to do something” -- here, referring to being reticent (enryo [延慮 = 遠慮]).

⁵Tsune no suzuri-bako mo oki-au-beshi [常の硯箱も置合べし].

Tsune no suzuri-bako [常の硯箱] means an “ordinary” suzuri-bako -- that is, a contemporary piece, one that did not have a name or reputation.

The attitude to modern-made pieces was rather different then than it is in chanoyu now. The present approach seems to have appeared when there were not enough renowned antiques to go around*, which, in turn, elevated the artisans working for, or appreciated by, the Senke to an almost super-human level -- with their work commanding prices comparable to many of the famous antiques, even though recently made.

___________

*Even in Rikyū’s day, contemporary pieces were considered expendable, and not regarded as being valuable. Indeed, their only real worth seems to have been sentimental (and, perhaps, aesthetic) -- though such things did not add to their market value. They were often enjoyed precisely because they were easily replaced -- so the appreciation here was of a different magnitude from the awe inspired by the great meibutsu (which had been used, owned, and treasured by the greatest chajin of the past).

⁶Mochiron meibutsu no kazari-yō to ha kokoro-mochi kawaru-koto nari to denju no yoshi [勿論名物のかざり樣とハ心持かハる事なりと傳授のよし].

This is a rather odd sentence.

Denju no yoshi [傳授のよし] is a rather strange construction, which seems to mean something like “(this) transmitted-teaching is good.” In other words, the teaching that “one should approach the display of meibutsu pieces with a different mindset than when dealing with ordinary objects” is a good teaching.

Regarding the phrase kazari-yō kokoro-e kawaru [飾樣心得カハル], Shibayama Fugen comments “with respect to a meibutsu versus an ordinary hitsu-dai, there is a difference in the way that these things are aligned with the kane.”

Tanaka Senshō essentially repeats the same observation in his notes on this entry as well, while elaborating upon it somewhat (throughout his very lengthy commentary on the Nampō Roku, Tanaka’s focus is always on the kane-wari aspect of the various arrangements).

⁷Kūkai [空海].

Kūkai [空海; dates unknown] was originally a functionary in the service of the shōgun's court*, at which time he was referred to as Tō-ukyō [嶋右京]†.

According to certain accounts, he seems to have been initiated into the details of chanoyu, and the decoration of the shoin, by Nōami‡ himself. He is said to have retired to Sakai after the end of his period of service.

Kūkai was the teacher of Dōchin.

__________

*Perhaps as a page or personal attendant. He is said, by some, to have been the koshō [小姓], or page, who waited on Nōami. (It should be noted that pages in Japan were not young boys, as they were in Europe.)

†The moniker can also be pronounced Shima-ukyō. This has lead to speculation that his family name may have been Tō [嶋] (possibly pronounced Shima), or perhaps another family name that included this kanji (like Shimada [嶋 田, 島 田], or Tajima [大嶋, 大島]).

The ukyō part of this title would refer to the place where his responsibilities lay; or perhaps (if he had no other responsibilities than being the page of one of the retired shōgun’s artistic companions, as some commentators assert) the part of Kyōto where his residence was located.

Ukyō describes the half of the inner city to the west of the central north-south avenue, the Suzaku ōji [朱雀大路] (located in the middle of the above photograph of a model of the old city), that extended from the southern Suzaku-mon [朱雀門] of the Imperial Palace (at the very top of the photo) to the Rashō-mon [羅生門] gate in what had been the southern wall of the city (the wall can be seen in the foreground of the photo, with the gate in the middle) -- though most of the wall had long since disappeared by Tō-ukyō’s/Kūkai’s time, while the Rashō-mon gatehouse itself still remained.

This traditional designation of Ukyō is not equivalent to the modern Ukyō-ku [右京区].

‡Nōami [能阿彌] died in 1471, but Kūkai's purported disciple, Araki Dōchin, was not born until 1504. While it is not impossible, there certainly is some reason to doubt the accuracy of the story -- at least as it has come down to us in the pages of Kanamori Sōwa’s history of chanoyu.

⁸Dōchin [道陳].

This was Araki Dōchin [荒木道陳; 1504 ~ 1562], also known as Kitamuki Dōchin [北向道陳] (from the location of his residence within the city-state of Sakai). He is said to have learned chanoyu and the details of the decoration of the shoin from Ukyō, after his retirement to Sakai (upon the death of the retired shōgun) -- though, if the story is true, Ukyō must have been an exceedingly old man (old enough to have caused remark -- of which there seems to be no evidence).

At any rate, Dōchin was Rikyū's first teacher, so this part of the transmission story would appear to be true.

——————————————–———-—————————————————

The two arguments presented in this entry -- one of which is ascribed to Sōami, and the other to his grandfather Nōami (though apparently Nōami’s opinion is stated according to the way it was later interpreted by Kūkai and Dōchin)* -- might be summed up in this way: Sōami appears to be saying that, with respect to the use of a piece that lacks a name (or reputation), “it might be better not to display it unless the host has a good reason” (or, “not unless he really wants to display it”); Nōami, on the other hand, when considering the same question, appears to ask “why not use it?”

Given the rather incoherent nature of this entry, however, I think it might be best to quote the entirety of Tanaka Senshō’s explanatory note -- since he is the only commentator who has made the effort to set his thoughts on this matter down on paper:

“The text [of this entry], as you can see, refers to objects that are being brought out [for display] on the tsukue-doko [机床]†. If this hitsu-dai is not a meibutsu, then the question arises as to whether it is [really] appropriate to display it [on the tsuke-shoin], or not. With respect to what might be called Sōami's sense of reticent hesitation, in the early days Nōami held that the lack of a name was not, in and of itself, an obstacle. For this reason, Kūkai [空海], Dōchin [道陳], and Rikyū [利休] -- as the proponents of a single school of thought -- displayed [objects of this sort] without reservation.

“Nevertheless, it can be supposed that both Sōami's style and Kūkai's style diverged [from Nōami's original, rather casual, approach] later.

“While, at least with respect to the display of a meibutsu hitsu-dai, there is no doubt that such things should be displayed as mine-sure [峰摺り]‡, it should be understood that this kind of alignment is said to be inappropriate when dealing with [more] ordinary objects.”

While Tanaka’s concern with mine-suri is well founded, the term (if not the idea of careful placement that it implies) would be anachronistic with respect to Book Four of the Nampō Roku, since Jōō was apparently unaware of this aspect of gokushin theory** during the early period (when he jotted down the notes that form the basis of this book)††.

___________

*I can not find any reference to a “hitsu-dai” [筆臺] in either the Kun-dai Kan Sa-u Chō Ki [君臺觀左右帳記], or the O-kazari Ki [御飾記]; and the only mention I have found of a suzuri-bako [硯筥 = 硯箱] is in the O-kazari Sho [御飾書], where the text states that the one displayed in the shōgun’s rooms should be made of “kara-ki” [唐木] -- which is a generic name for any wood not native to Japan (ebony or rosewood being the most likely material, in this case). The O-kazari Sho, it must be remembered, is the version of Sōami’s work prepared for the Tokugawa shōgun’s household, and it contains many modifications and changes of wording from the original treatise upon which it was based.

At any rate, since neither Nōami nor Sōami even mentions a “hitsu-dai,” and since the brushes and ink are always shown leaning against a hitsu-ka [筆荷 = 筆架, also pronounced fude-kake], it is difficult to accept the premise upon which this entry is based as authentic. Furthermore, philosophical discussions such as this are not entered into in either of these works: basically, both the Kun-dai Kan Sa-u Chō Ki, and the O-kazari Ki, are effectively catalogs enumerating the various rooms in the shōgun’s mansion, and the arrangement of art objects that were distributed on the various shelves and display areas therein. Any rules -- such as that a kōgō with a picture of a flower on it should be arranged so that the root end is at the front of the piece when viewed by the guest -- are incidental to the nature of the material covered in the books (and almost always relates to the specific objects mentioned in the descriptions of the arrangements).

Nōami and Sōami were important officials in the Ashikaga shōgun’s household, but they were not public figures. There is nothing to suggest that these men ever gave public workshops -- indeed, revealing these secrets outside of the household would likely have been punished severely (Nōami and his family were technically foreigners, and so enjoyed no real protection by law). The dissemination of the information in the Kun-dai Kan Sa-u Chō Ki and the O-kazari Ki was most likely carried out by other, much lower, people employed in the households, in the form of pirated and unofficial copies of their writings (perhaps produced in the same way as were the original copies of the Nampō Roku that circulated during the second half of the Edo period -- from memory).

And again, returning to their writings, these books deal exclusively with the arrangements created by Nōami for specific venues (most entries begin with a detailed description of the location and size of the room, in the shōgun’s residence, so as to prevent the arrangements from being effected in the wrong setting), using very specific objects. Nothing is said in either book that could be interpreted as encouragement for the reader to attempt to recreate these arrangements somewhere else. Indeed, the primary purpose of these documents seems to be to enable the staff to set up the rooms again, after everything had been put away (in this period it appears that everything was generally put away for the night, with the objects taken back out, and the arrangements restored, the next day -- if the shōgun’s presence made that appropriate: this is why old scrolls almost always exhibit the extreme wear-and-tear that they generally do, and why tutorials from the sixteenth century stress that care must be taken to prevent these scrolls from any unnecessary exposure to moisture, such as covering the mouth with ones fan while inspecting them).

As a result, it seems fairly certain that this entry was fabricated by someone during the early Edo period, but also someone outside of the shōgun’s household (thus probably eliminating the bakufu as well). Consequently, the most likely candidate would have been someone affiliated with the Sen family, who wanted to incorporate their teachings and speculations (while simultaneously reinforcing their version of the orthodox lineage) into this book.

†Tsukue-doko [机床]: the word Tanaka Senshō uses for the tsuke-shoin; the dashi-fuzukue, or built-in writing desk.

‡Mine-sure [峰摺り] means that an object is aligned exactly with the kane on which it rests: the exact center of the object lies exactly on the center of the kane. Such exceptionally careful placement is reserved for objects of the very highest status.

**It seems that Jōō’s original interest in the young Rikyū was stimulated by his desire to be made party to a set of teachings which Kitamuki Dōchin apparently preferred to keep to himself (and his disciples). Since Rikyū was no longer to be counted among that number (on account of the loss of his family’s fortune), Dōchin seems to have dangled him in front of Jōō as a possible solution to this conundrum.

At the time of their presumed first meeting, Rikyū was in his early 20s, while Jōō had already developed the basic form of the chakai, and was well on his way to amassing the collection of tea utensils and other meibutsu works of art that earned him the accolade of the greatest chajin of the day.

††Tanaka Senshō was naturally operating under the assumption that the entirety of the Nampō Roku was either written by Nambō Sōkei, or represented a transcription of things that Rikyū had related to him, since that is how Tachibana Jitsuzan represented the contents of this collection. Of course this way of thinking was based largely on the Sen family’s reconstructed mythology which (as a consequence of the machi-shū, lead by Imai Sōkyū, having repudiated most of Rikyū’s legacy in the immediate aftermath of his seppuku) was founded on the assumption that many things actually said and done by Jōō, and Furuta Sōshitsu, should be credited to Rikyū. Which neither restored the record of Rikyū’s accomplishments, nor did justice to the historical innovations effected by Jōō, and Oribe.

0 notes