#Sir Roger Casement

Text

#OTD in 1918 – John Devoy claims Roger Casement to blame for the 1916 Easter Rising’s failure.

New York-based John Devoy, editor of the recently suppressed Gaelic American has claimed credit for being the key individual behind the ‘German Sinn Féiner’ efforts to launch a revolt in Ireland in 1916. The claim comes in a letter, a copy of which was published last month in the USA.

The letter, discovered on the premises of Lawrence DeLacey at the time of his arrest in California in August…

View On WordPress

#1916 Easter Rising#Co. Kerry#England#Eoin MacNeill#Germany#Ireland#John Devoy#New York City#Sinn Fein#Sir Roger Casement#United States

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

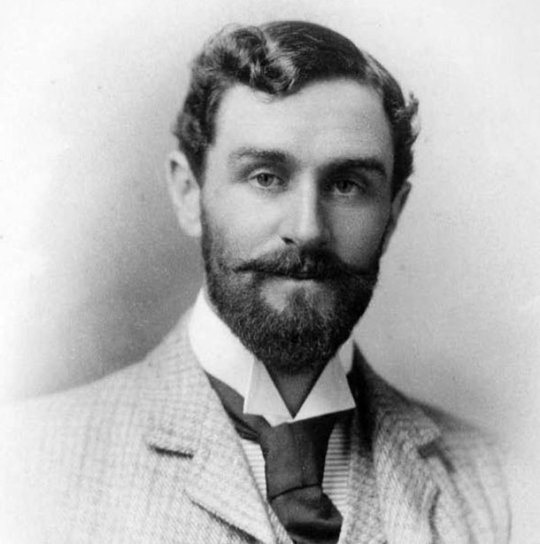

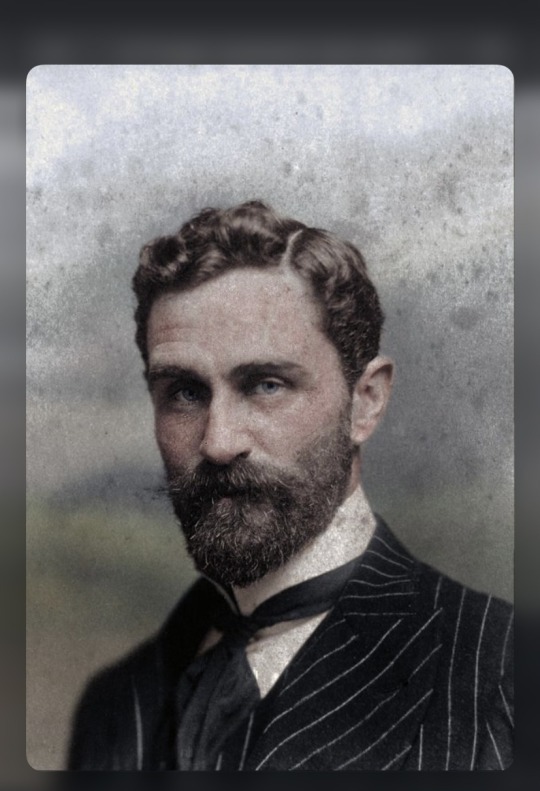

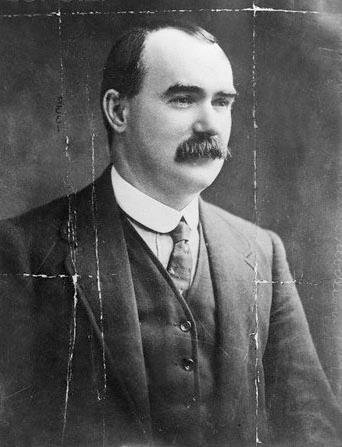

'Roger Casement (1864-1916), Patriot and Revolutionary' as depicted by Irish painter Sarah Purser (1848-1943).

13 notes

·

View notes

Note

What do you think about as often as men think about the Roman Empire?

That meme is probably dead by now, but I’ve seen you pop off about England’s fuckery and am curious of anything else that gets you so heated

I think about the Roman Empire at least twice a day. Julius Caesar, Livia Drusilla, Cicero, Caligula, Tiberias, Claudius, Augustus, Agrippa, I mean why wouldn't I?

Michael Collins, Countess Markievicz, Roger Casement, really the entire 1916 rising except de Valera who can fuck off and die (yes, I know he's dead but do so again sir)

The Famine

Tutankhamen and his burial chamber.

Cursed jewellery - the Lusitania Tiara, the Hesse Strawberry Leaf Tiara

How Felix Yusopov was simply the GOAT

Dollar Princesses/Cash for Coronets

The Romanovs - suffering from this brain rot since I was 4.

At the moment it's the horrific birth of Kaiser Wilhelm II and the effect it had on him and his mom, Vicky.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

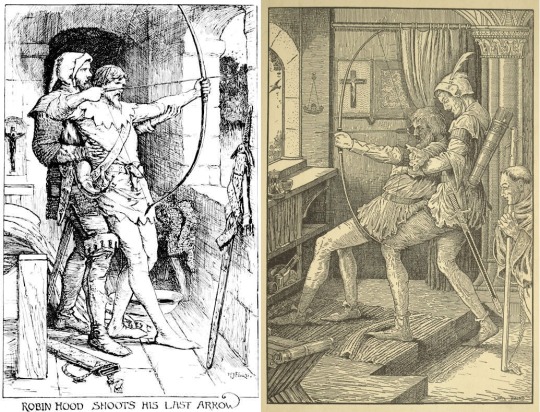

Robin Hood's Last Arrow

A common trope in legends of outlaws and other folk heroes is that they’re invisible when they choose to hide, and invincible when they choose to fight. (At least when they fight for real; in less serious brawls they often lose the fight and gain a new ally!) So the only way to bring them down is betrayal.

This is also the case in the death of Robin Hood, as recounted in A Gest of Robyn Hode (15th century), Robin Hood’s Death (17th/18th century ballad), and Howard Pyle’s The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood (1883). Robin goes to a priory to receive medical attention, which at the time means bloodletting. But the prioress who’s supposed to heal him betrays him: the later versions specify that she cuts him deep instead, and he slowly bleeds to death, while there may be an accomplice who attacks him in his weakened state.

Here’s our earliest account of the outlaw’s death, sparse in details, possibly because the story was already established in oral tradition:

Then bespoke good Robyn,

In place where as he stood,

’To morrow I must to Kyrkesly,

Craftly to be let blood.’

Sir Roger of Donkaster,

By the prioress he lay,

And there they betrayed good Robyn Hode,

Through their false play.

Christ have mercy on his soul,

That died on the road!

For he was a good outlaw,

And did poor men much good.

— A Gest of Robyn Hood (I’m modernising the spelling)

So in the Gest he dies “on the road”, and in the first version of Robin Hood’s Death (c. 1650) he is buried by the road: too weak to walk, he asks Little John to carry him “to yonder streete” and bury him there, with his sword at his head, his arrows at his feet, and his yew-bow by his side. But in the later version of Robin Hood’s Death (1786) we get a more poetic burial. A mortally wounded Robin shoots his last arrow and asks to be buried wherever it lands.

But give me my bent bow in my hand,

And a broad arrow I’ll let flee;

And where this arrow is taken up,

There shall my grave digged be.

‘Lay me a green sod under my head,

And another at my feet;

And lay my bent bow by my side,

Which was my music sweet;

And make my grave of gravel and green,

Which is most right and meet.

‘Let me have length and breadth enough,

With a green sod under my head;

That they may say, when I am dead

Here lies bold Robin Hood.’

— Robin Hood’s Death (Child Ballad 120B; more info here)

In Howard Pyle’s retelling of that story, Robin lies dying in the priory, with Little John by his side and a window to look through.

Meantime the sun dropped slowly to the west, till all the sky was ablaze with a red glory. Then Robin Hood, in a weak, faltering voice, bade Little John raise him that he might look out once more upon the woodlands; so the yeoman lifted him in his arms, as he bade, and Robin Hood’s head lay on his friend’s shoulder. Long he gazed, with a wide, lingering look, while the other sat with bowed head, the hot tears rolling one after another from his eyes, and dripping upon his bosom, for he felt that the time of parting was near at hand.

Then, presently, Robin Hood bade him string his stout bow for him, and choose a smooth fair arrow from his quiver. This Little John did, though without disturbing his master or rising from where he sat. Robin Hood’s fingers wrapped lovingly around his good bow, and he smiled faintly when he felt it in his grasp, then he nocked the arrow on that part of the string that the tips of his fingers knew so well. “Little John,” said he, “Little John, mine own dear friend, and him I love better than all others in the world, mark, I prythee, where this arrow lodges, and there let my grave be digged. Lay me with my face toward the East, Little John, and see that my resting place be kept green, and that my weary bones be not disturbed.”

As he finished speaking, he raised himself of a sudden and sat upright. His old strength seemed to come back to him, and, drawing the bowstring to his ear, he sped the arrow out of the open casement. As the shaft flew, his hand sank slowly with the bow till it lay across his knees, and his body likewise sank back again into Little John’s loving arms; but something had sped from that body, even as the winged arrow sped from the bow.

— Howard Pyle, The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood (1883)

That was really cool and really influential. The flurry of Robin Hood publications that followed Pyle’s Adventures tended to include and illustrate that scene (whereas I’ve seen only one illustration dating before that). But I should clarify that Pyle didn’t rescue the scene from complete oblivion: earlier, in 1828, it had been the subject of a very Romantic™ poem by Bernard Barton, who lauded “freedom’s rude and lawless home beneath the forest bough”:

“Now raise me on my dying bed,

Bring here my trusty bow,

And ere I join the silent dead,

My arm that spot shall show.” [...]

With kindling glance and throbbing heart

One parting look he cast,

Sped on its way the feathered dart,

Sank back! and breathed his last!

And where it fell they dug his grave,

Beneath the greenwood tree;

Meet resting-place for one so brave,

So lawless, frank, and free.

— Bernard Barton, “The Death of Robin Hood” (1828)

We haven’t seen the last arrow in recent adaptations, but there’s an echo in Robin of Sherwood, a scene with the same resonance even if the circumstances are different: Robin of Loxley makes his last stand on a hill, fending off the Sheriff of Nottingham and like a million men all by his lonesome (because longbow range). And just as the Sheriff wonders how many bloody arrows this man has, he picks his last one, dramatically throws away the quiver, and this time doesn’t aim. The last arrow isn’t for killing, it’s his own funerary rite and a parting gift to the forest. It's letting go without ever giving up.

He looks down, raises up the bow, and lets it loose blindly, to go wherever it may, where chance and fate decides. The arrow flies over the soldiers’ heads, and importantly, we don’t see where it lands, we just know it went somewhere towards Sherwood. And in the face of inescapable death, the now unarmed and surrounded Robin smiles.

Now that’s a fucking poetic last arrow.

@tuulikki

#The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood#Howard Pyle#trs#robin hood#Robin of Sherwood#A Gest of Robyn Hode#swinging from the gallows tree#rogues in fiction#the phantom of liberty#outlaw#analysis

208 notes

·

View notes

Text

If only Sir Roger Casement was the immortal time traveler.

0 notes

Text

in this house we stan roger casement instead of oscar wilde

#rory maceasmann#roger casement#sir roger casement#casement#oscar wilde#irish history#history#world history#european history#classic literature#english literature#literature

154 notes

·

View notes

Text

Those Executed For Involvement In the Irish Easter Rising in 1916

Francis Sheehy-Skeffington (died age 37)

Sheehy-Skeffington tried to organise a citizen police force to stop looting on the Tuesday of the Rising. Heading home, he was arrested in for no reason by British troops. Capt JC Bowen-Colthurst used him as a hostage while attacking the shop of Alderman James Kelly, at the top of Camden Street. Bowen-Colthurst destroyed the shop with grenades, and shot dead a 17-year-old boy before marching Sheehy-Skeffington and two journalists to Portobello Barracks. The next morning, they unaware they were going to be shot to death until moments before it occurred. They were executed the next morning on April 26th, 1916. Those involved attempted to cover up what they did.

Thomas “Tom” Clarke (died age 58)

Clarke was stationed at headquarters in the General Post Office during the Easter Week. Clarke wrote on the wall of the house after surrender on April 29th, "We had to evacuate the GPO. The boys put up a grand fight, and that fight will save the soul of Ireland." He was arrested after the surrender. He and other rebels were taken to the Rotunda where he was stripped of his clothing in front of the other prisoners. He was later held in Kilmainham Gaol. He was court-martialled and sentenced to death. Before his execution, he asked his wife Kathleen to give this message to the Irish People:

"My comrades and I believe we have struck the first successful blow for freedom, and so sure as we are going out this morning so sure will freedom come as a direct result of our action . . . In this belief, we die happy."

He was then executed by firing squad on May 3rd, 1916.

Patrick Pearse (died age 36)

Easter Monday, April 24th 1916, it was Pearse who read the Proclamation of the Irish Republic from outside the General Post Office, the headquarters of the Rising. Pearse was the person most responsible for drafting the Proclamation, and he was chosen as President of the Republic. Six days after he issued the order to surrender. He was court-martialled and executed by firing squad on may 3rd, 1916. He was said to be whistling as he came out of his cell to be killed. The day before his death he wrote:

"When I was a child of ten I went down on my bare knees by my bedside one night and promised God that I should devote my life to an effort to free my country. I have kept that promise. As a boy and as a man I have worked for Irish freedom. The time, as it seemed to me, did come, and we went into the fight. I am glad we did. We seem to have lost. We have not lost. To refuse to fight would have been to lose, to fight is to win. We have kept faith with the past and handed on a tradition to the future."

Thomas MacDonagh (died age 37)

MacDonagh's battalion was stationed at Jacob's Biscuit Factory. Despite MacDonagh's rank and the fact that he commanded one of the strongest battalions, they saw little fighting. MacDonagh received the order to surrender on April 30th, though his battalion was prepared to continue. Following the surrender, MacDonagh was court martialled, and executed by firing squad on May 3rd, 1916. In his last message to the Irish people he wrote:

"I, Thomas MacDonagh, having now heard the sentence of the Court Martial held on me today, declare that in all my acts, all the acts for which I have been arraigned. I have been actuated by one motive only, the love of my country, and the desire to make her a sovereign, independent state."

Joseph Mary Plunkett (died age 28)

Following the surrender Plunkett was held in Kilmainham Gaol, and faced court martial. Seven hours before his execution, he was married in the prison chapel to his sweetheart Grace Gifford, a Protestant convert to Catholicism, whose sister, Muriel, had years before also converted and married his best friend Thomas MacDonagh, who was also executed for his role in the Easter Rising. Grace never married again after his death on May 4th, 1816. Days before his sentence Plunkett had written in a letter to Grace:

"Listen--if I live it might be possible to get the Church to marry us by proxy- there is such a thing but it is very difficult I am told. Father Sherwin might be able to do it. You know how I love you. That is all I have time to say. I know you love me and I am very happy."

Edward “Ned” Daly (died age 25)

Daly's battalion, stationed in the Four Courts and areas to the west and north of the centre of Dublin, saw the most harsh fighting of the rising. He was forced to surrender his battalion on April 29th by Patrick Pearse. He was executed by firing squad on May 4th 1916. Men in his battalion spoke of him as a good leader.

Michael O’Hanrahan (died age 38)

O’Hanrahan was second in command of Dublin's 2nd battalion under Commandant Thomas MacDonagh. He fought at Jacob's Biscuit Factory, though the battalion saw little action other than intense sniping throughout Easter week. O'Hanrahan was executed by firing squad on May 4th 1916 at Kilmainham Jail. His brother, Henry O'Hanrahan, was sentenced to penal servitude for life for his role in the Easter Rising.

William “Willie” Pearse (died age 34)

Willie followed his brother into the Irish Volunteers and the Republican movement. He took part in the Easter Rising in 1916, always staying by his brother's side at the General Post Office. Following the surrender he was court-martialled and sentenced to be executed. It has been said that as he was only a minor player in the struggle it was his surname that condemned him. However, at his court martial he rather exaggerating his involvement. On May 3rd, William was granted permission to visit his brother in Kilmainham Gaol and to see him for the final time. While Willie was en route, Patrick was executed first and they never saw one another again. Willie was executed on May 4th, 1916.

John MacBride (died age 47)

In 1905 MacBride joined other Irish nationalists in preparing for an insurrection. Because he was so well known to the British, the leaders thought it wise to keep him outside their secret military group planning a Rising. He was in Dublin early on Easter Monday morning to meet his brother Dr. Anthony MacBride, who was arriving from Westport to be married on the Wednesday. The Major walked up Grafton St and saw Thomas MacDonagh in uniform and leading his troops. He offered his services and was appointed second-in-command at the Jacob's factory. After the Rising, MacBride, following a court martial under the Defence of the Realm Act, was shot by British troops in Kilmainham Gaol, Dublin.

He was executed on May 5th 1916, two days before his forty-eighth birthday. Facing the British firing squad, he said he did not wish to be blindfolded, saying:

"I have looked down the muzzles of too many guns in the South African war to fear death and now please carry out your sentence."

He is buried in the cemetery at Arbour Hill Prison in Dublin.

Executed two days before his 54th birthday on May 5th.

Éamonn Ceannt (died age 34)

After the unconditional surrender of the 1916 fighters, Eamonn Ceannt was detained. While Ceannt was being picked for trial, volunteer James Couhlan remembers him being determined in looking after the welfare of “the humblest of those who had served under him”. Ceannt was tried under court martial as demanded by General Maxwell. May 2nd, Ceannt was sent to Kilmainham Gaol to face trial and execution.

Written a few hours before his execution from cell 88 in Kilmainham Gaol, he wrote:

“I leave for the guidance of other Irish Revolutionaries who may tread the path which I have trod this advice, never to treat with the enemy, never to surrender at his mercy, but to fight to a finish...Ireland has shown she is a nation. This generation can claim to have raised sons as brave as any that went before. And in the years to come Ireland will honour those who risked all for her honour at Easter 1916.”

Ceannt was held in Kilmainham Gaol until his execution by firing squad on May 8th 1916. He is buried at Arbour Hill.

Michael Mallin (died age 41)

When Connolly was inducted into the Irish Republican Brotherhood in January 1916. On Easter Monday Mallin departed from Liberty Hall at 11:30am to take up his post at St Stephen's Green with his small force of ICA men and women. Upon arriving at the park they evacuated it, dug trenches, erected kitchen and first aid stations, and constructed barricades in the surrounding streets. Mallin planned to occupy the Shelbourne Hotel, located on the north-east side of the park, but insufficient troops prevented him from doing so. The next morning under intense machine gun fire Mallin ordered his troops to retreat to the Royal College of Surgeons on the west side of the park. The garrison remained in the barricaded building for the remainder of the week.

Mallin surrendered on April 30th 1916. The garrison was taken first to Dublin Castle then to Richmond Barracks, where Mallin was separated for court-martial. At his court-martial he downplayed his involvement. In his statement, Mallin stated:

“I had no commission whatever in the Citizen Army. I was never taken into the confidence of James Connolly. I was under the impression that we were going out for manoeuvres on Sunday . . . Shortly after my arrival at St Stephen's Green the firing started and Countess Markievicz ordered me to take command of the men as I had been so long associated with them. I felt I could not leave them and from that time I joined the rebellion."

Mallin was found guilty and transported to Kilmainham Gaol for his execution. He was executed May 8th 1916. The night before his execution he was visited in his cell by his mother, three of his siblings, his pregnant wife and their four children. In his last letter to his wife, who was pregnant with their fifth child, Mallin said:

"I find no fault with the soldiers or the police [I ask you] to pray for all the souls who fell in this fight, Irish and English . . . so must Irishmen pay for trying to make Ireland a free nation."

He wrote to his children:

“Una my little one be a Nun Joseph my little man be a Priest if you can James & John to you the care of your mother make yourselves good strong men for her sake and remember Ireland”

His funeral mass took place at the Dominican Church in Tallaght on May 13th, 1917. People from the procession clashed with police outside the church with two policemen injured.

Con Colbert (died age 37)

In the weeks leading up to the Rising, he acted as bodyguard for Thomas Clarke. During Easter Week, he fought at Watkin's Brewery, Jameson's Distillery and Marrowbone Lane. They were marched to Richmond Barracks after surrender, where Colbert would later be court-martialled. Transferred to Kilmainham Gaol, he was told on Sunday May 7th he was to be shot the following morning. He wrote no fewer than ten letters during his time in prison. During this time in detention, he did not allow any visits from his family; writing to his sister, he said a visit "would grieve us both too much".

The night before his execution he sent for Mrs. Ó Murchadha who was also being held prisoner. He told her he was "proud to die for such a cause. I will be passing away at the dawning of the day." Holding his bible, he told her he was leaving it to his sister. He handed her three buttons from his volunteer uniform, telling her "They left me nothing else," before asking her when she heard the volleys of shots in the morning for Éamonn Ceannt, Michael Mallin and himself would she say a Hail Mary for the souls of the departed. The soldier who was guarding the prisoner began crying according to Mrs. Ó Murchadha, and recorded him saying "If only we could die such deaths."

Colbert was shot by firing squad the next morning on May 8th 1916.

Sean Heuston (died age 25)

Heuston was the Officer Commanding of the Volunteers in the Mendicity Institution on the south side of Dublin city. Heuston was to hold this position for three or four hours, to delay the advance of British troops. This delay was necessary to give the headquarters staff time to prepare their defences. Heuston was arrested after the surrender and transferred to Richmond Barracks. O May 4th 1916, he was tried by court martial. May 7th 1916, the verdict of the court martial was communicated to him that he had been sentenced to death and was to be shot at dawn the following morning.

Prior to his execution he was attended by Father Albert in his final hours. Father Albert wrote an account of those hours up to and including the execution:

“…We were now told to be ready. I had a small cross in my hand, and though blindfolded, Seán bent his head and kissed the Crucifix; this was the last thing his lips touched in life. He then whispered to me: ‘Father, sure you won’t forget to anoint me?’ I had told him in his cell that I would anoint him when he was shot. We now proceeded towards the yard where the execution was to take place; my left arm was linked in his right, while the British soldier who had handcuffed and blindfolded him walked on his left. As we walked slowly along we repeated most of the prayers that we had been saying in the cell. On our way we passed a group of soldiers; these I afterwards learned were awaiting Commandant Mallin; who was following us. Having reached a second yard I saw there another group of military armed with rifles. Some of these were standing, and some sitting or kneeling. A soldier directed Seán and myself to a corner of the yard, a short distance from the outer wall of the prison. Here there was a box (seemingly a soap box) and Sean was told to sit down upon it. He was perfectly calm, and said with me for the last time: ‘My Jesus, mercy.’ I scarcely had moved away a few yards when a volley went off, and this noble soldier of Irish Freedom fell dead. I rushed over to anoint him; his whole face seemed transformed and lit up with a grandeur and brightness that I had never before noticed.”

Father Albert concluded:

“Never did I realise that men could fight so bravely, and die so beautifully, and so fearlessly as did the Heroes of Easter Week. On the morning of Sean Heuston's death I would have given the world to have been in his place, he died in such a noble and sacred cause, and went forth to meet his Divine Saviour with such grand Christian sentiments of trust, confidence and love.”

Thomas Kent (died age 50)

During the Easter Rising, the Kent residence was raided in a gunfight lasted for four hours. Eventually the Kents were forced to surrender. Thomas and William was tried by court martial on the charge of armed rebellion. His brother was acquitted, but Thomas was sentenced to death and executed by firing squad in Cork on May 9th 1916. He was buried in the grounds of Cork Prison.

Sean Mac Diarmada (died age 33)

September 1915, he joined the secret Military Committee of the IRB. In 1914 he said:

"the Irish patriotic spirit will die forever unless a blood sacrifice is made in the next few years.”

Due to his disability, Mac Diarmada took little part in the fighting of Easter week, but was stationed at the headquarters in the General Post Office. Following the surrender, he nearly escaped execution by blending in with the large body of prisoners. He was eventually recognised by Daniel Hoey of G Division. Following a court-martial on May 9th, Mac Diarmada was executed by firing squad on May 12th. In his final letter he wrote:

"Miss Ryan, she who in all probability, had I lived, would have been my wife".

She and her sister, Phyllis also visited Kilmainham Gaol before his execution. Before his execution, Mac Diarmada wrote:

"I feel happiness the like of which I have never experienced. I die that the Irish nation might live!”

James Connolly (died age 47)

Connolly considered the rest of the leaders too bourgeois and unconcerned with Ireland's economic independence. During the Easter Rising, Connolly was Commandant of the Dublin Brigade and was de facto commander-in-chief. Following the surrender, he said to other prisoners:

"Don't worry. Those of us that signed the proclamation will be shot. But the rest of you will be set free."

Connolly was not held in gaol, but in a room at the State Apartments in Dublin Castle, which had been converted to a first-aid station for troops recovering from the war. Connolly was sentenced to death by firing squad for his part in the rising. On May 12th 1916 he was taken by military ambulance to Royal Hospital Kilmainham, across the road from Kilmainham Gaol, and from there taken to the gaol, where he was to be executed. Visited by his wife, and asking about public opinion, he commented:

"They will all forget that I am; an Irishman."

Connolly had been so badly injured from the fighting but the execution order was still given and he was unable to stand before the firing squad; he was carried to a prison courtyard on a stretcher. His absolution and last rites were administered by a Capuchin, Father Aloysius Travers. Asked to pray for the soldiers about to shoot him, he said:

"I will say a prayer for all men who do their duty according to their lights."

Instead of being marched to the same spot where the others had been executed, at the far end of the execution yard, he was tied to a chair and then shot. His body (with other leaders) was put in a mass grave without a coffin. The executions of the rebel leaders deeply angered the majority of the Irish population, most of whom had shown no support during the rebellion.

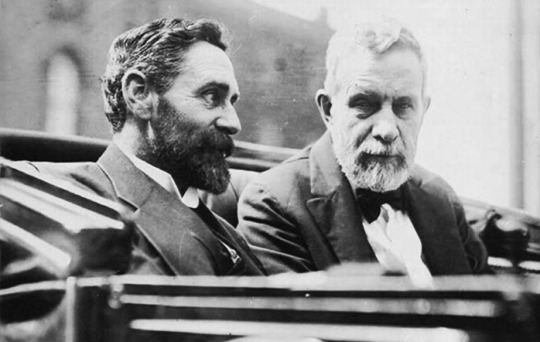

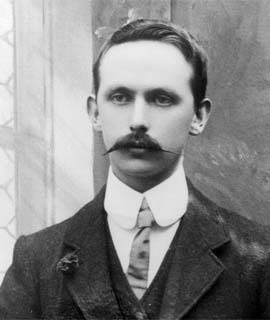

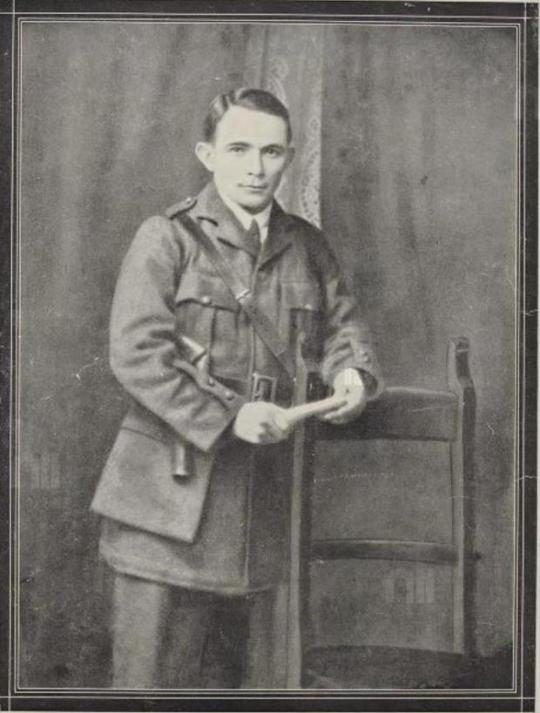

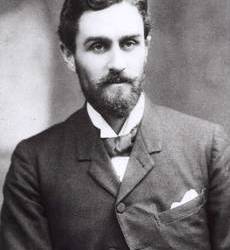

Sir Roger Casement (died age 51)

October 1914, Casement sailed for Germany via Norway. Casement spent most of his time in Germany seeking to recruit an Irish Brigade from among more than 2,000 Irish prisoners-of-war taken in the early months of the war and held in the prison camp of Limburg an der Lahn. His plan was that they would be trained to fight against Britain in the cause of Irish independence. Casement did not learn about the Easter Rising until after the plan was fully developed. The German weapons never landed in Ireland; the Royal Navy intercepted the ship transporting them.

Casement departed Germany in a submarine. In the early hours of April 21st 1916, three days before the rising began, the German submarine put Casement ashore. Suffering from a recurrence of the malaria, and too weak to travel, he was discovered at McKenna's Fort and arrested on charges of treason, sabotage and espionage against the Crown.

"He was taken to Brixton Prison to be placed under special observation for fear of an attempt of suicide. There was no staff at the Tower [of London] to guard suicidal cases."

At Casement's highly publicised trial for treason, the prosecution had trouble arguing its case. Casement's crimes had been carried out in Germany. During the trial, Casement’s personal diary detailed his homosexual encounters was uncovered. The British government circulated fake reports to portray Casement as a sexual deviant. Casement tried to appeal the violation of his human rights and against his conviction and death sentence. On the day of his execution, Casement was received into the Catholic Church at his request. He was attended by two Catholic priests. One said of Casement that he was:

"a saint… we should be praying to him [Casement] instead of for him".

Casement was hanged at Pentonville Prison in London on August 3rd 1916. His last word was “Ireland”.

#irish history#history#irish rebellion 1916#eastern rising#Francis Sheehy-Skeffington#thomas clarke#tom clarke#Patrick Pearse#Thomas MacDonagh#Joseph Mary Plunkett#Sir Roger Casement#joseph plunkett#roger casement#James Connolly#Sean Mac Diarmada#Thomas Kent#Sean Heuston#Con Colbert#Michael Mallin#Éamonn Ceannt#John MacBride#William Pearse#willie pearse#Edward daly#ned daly#Michael O’Hanrahan

515 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Massacre at Amritsar one of British Empire’s many despicable events This letter appeared in The Irish News today Wednesday July 15th 2020 IT WAS interesting to read in the excellent 'On this day' (July 9) that Edward Carson had defended the actions of…

#80th Anniversary#Anita Anand#Black Lives Matter#book#Brigadier General Dyer#Caxton Hall - London#Edward Carson#Execution of Mr Singh#House of Commons#humanitarian#India#July 31st#Massacre at Amritsar in India#Massacre at Amritsar one of British Empire&039;s many despicable events#Pentonville Prison#Sir Roger Casement#The Patient Assassin#Twenty-One-Years#Udham Singh

0 notes

Text

Sir Roger Casement | The Man Hanged as a Traitor Who Took on the Devil

Roger Casement (1864-1916) was an Irish nationalist and British consular official, whose attempt to secure aid from Germany in the struggle for Irish independence led to his execution by the British for the crime of high treason.

Born on 1 September, 1864, in Kingstown, to a Protestant father and Catholic mother, Roger David Casement was heir to two radically different traditions in Ireland. As…

View On WordPress

#1916 Easter Rising#Africa#Antrim#Banna Strand#Belgium#Congo#Dublin#England#Germany#Ireland#Irish Brigade#London#Nationalist#Peru#Roger Casement#Sir Roger Casement#U-Boat

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

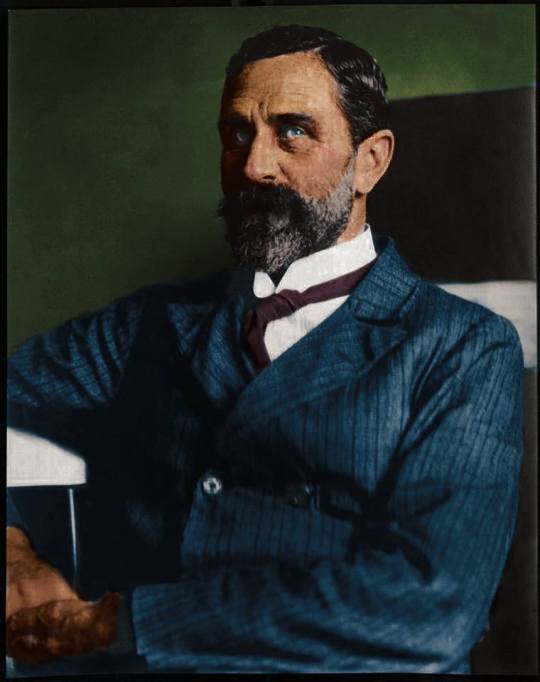

It is rare for a cartoon from a newspaper to make it's way onto this blog. But here it is-the moral giant Sir Roger Casement (1864-1916) in the dock vs a small rotund and shamelessly immoral England as the judge. Distortions in perspective have long been the shorthand in newspaper cartoons. Please left click here to read the article the image comes from, a 2016 online republishing of a 1916 newspaper report on Casement being put on trail for breaking a fourteenth century law that most did not know existed, it was that little used. But in the fevered war time setting the end justified the means and the British Empire decided Casement had to die. His argument for a future Ireland to secede from the British Empire lived on and found it's cause and effect in other people who achieved what Casement could not.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

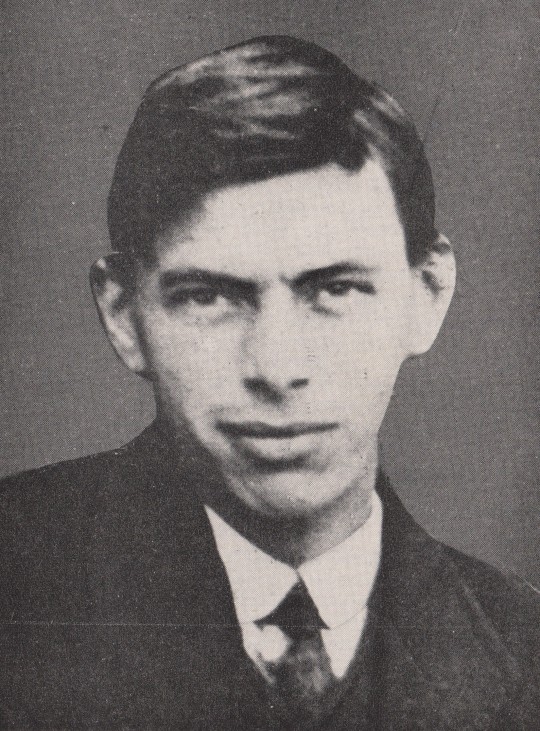

Roger Casement

Sir Roger David Casement (1864-1916), also called Ruairí Dáithí Mac Easmainn, was a diplomat, activist, and Irish nationalist. Called the "father of twentieth-century human rights investigations", his work in the Congo and Peru were some of the most important investigations of human rights abuses in history. An anti-imperialist, he was stripped of his knighthood and executed for high treason. The British government used proof that he was gay to turn international opinion against him.

Born in Dublin and educated in Ireland, Casement went to work in Liverpool and then for the British Colonial Service, where he took overseas postings as saw almost immediately that European colonialism was not a 'civilizing influence' but in fact a system of widespread abuse.

Casement worked with Joseph Conrad (Heart of Darkness), where they found that the actions of King Leopold II of Belgium in the Congo Free State were a reign of terror and human rights abuses. The Casement Report of 1904, when published, was instrumental in Leopold II finally relinquishing his private holdings in Africa.

Next, Casement went to Brazil. His work in detailing the abuses by the Peruvian Amazon Company (PAC) against the Putumayo, an indigenous group of the Peruvian Amazon, including severe physical violence and abuse by the Peruvian military against workers, causing the collapse of the widespread collapse of the PAC.

Casement supportws Irish independence and anti-imperialism. His work emphasized the dignity of indigenous peoples in the Global South, and he learned to speak several languages from these regions. His work supported the end of the British Raj in India and the Irish rebellion.

Casement was eventually captured and sentenced to high treason for his efforts to recruit Irish prisoners of war to fight against the English. The trial was highly publicized, in part due to the publishing of Casement's "Black Diaries", which contained accounts of his male lovers. Though it was controversial for a time, recent analyzes have conclusively proven that the Black Diaries are real and from Casement.

A hero in his time and in ours, Roger Casement's example as an anti-imperialist willing to publish accounts of abuses and bring down large corporations serve as an inspiration.

#history#world history#long post#indigenous history#african history#british history#english history#south american history#irish history#brazil#peru#congo#leopold ii#roger casement#irish nationalism#irish independence#human rights#activism#socialism#gay#gay history#gay men in history#Ruairí Dáithí Mac Easmainn

23 notes

·

View notes

Note

I was thinking about that “Are there any gays in Ireland?” ask you got a few weeks ago and thought of a great answer (besides Mr. Wilde himself):

Sir Roger Casement, the original himbo (to grossly bastardize his actual accomplishments)

Roger Casement is one of the most badass and bravest men of history.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Easter 1916: Roger Casement

Born in 1864 to a Dublin Anglo-Irish Protestant family, Sir Roger Casement worked for commercial interests in the Congo Free State starting in the 1880s. Initially under the impression that European colonization of Africa was a good thing, he quickly became disillusioned with the horrific abuses of empire. His 1904 Congo Report exposed awful conditions for colonized peoples, and made him known to the world as an early human rights activist.

In 1905, the British Foreign Service Office sent Casement to Brazil and then to Peru, where he continued to investigate and expose the treatment of native peoples under European colonization. During his time in Africa and South America, he began to understand Ireland's situation as a colony of the British crown.

In 1913, back in Ireland, Casement aided the republican movement. Initially, he had been in support of Sinn Fein's early moderate nationalism, but as the First World War sprang up he began to agree with more radical factions of the nationalist cause.

In 1914, Casement negotiated a tentative alliance with Germany for the proposed Irish Free State, and spent time in German prisoner-of-war camps where he promised Irish POWs their freedom if they would come back to Dublin with him and join his cause.

When Casement returned to Ireland just days before the Rising, he was captured and held by the British. The Kerry Irish Volunteers wanted to recapture him, but orders came from Dublin to keep the peace until Easter Monday.

During Casement's trial and appeal, the British government circulated his private writings known as the Black Diaries. If the Diaries are indeed Casement's and not forgeries (experts through the years have reached both conclusions, and recently it has been claimed that the British government forged them), they proved him guilty of homosexuality, a crime at the time. In circulating the documents, Britain likely hoped to keep people from speaking out on Casement's behalf. Still, those urging against Casement's execution included his family from Antrim, William Butler Yeats, Arthur Conan Doyle, George Bernard Shaw, and the United States Senate.

Roger Casement was stripped of his knighthood in June 1916, and hanged in August. Whether or not he wrote the Black Diaries, he likely died for them. On the day of his death, he was received into the Catholic Church, with one priest remarking that he should be a saint: "we should be praying to him instead of for him".

Today, Casement is remembered as an Irish hero and the father of the modern human rights movement. He is buried in Dublin: Britain continues to deny his last wish to lie with his family in Antrim.

#sorry this one got so long - as a gay northern irish protestant with family in antrim it hit close to home#easter rising 1916#irish history#irish#history#ireland#roger casement#the black diaries

25 notes

·

View notes