#South Asian women

Text

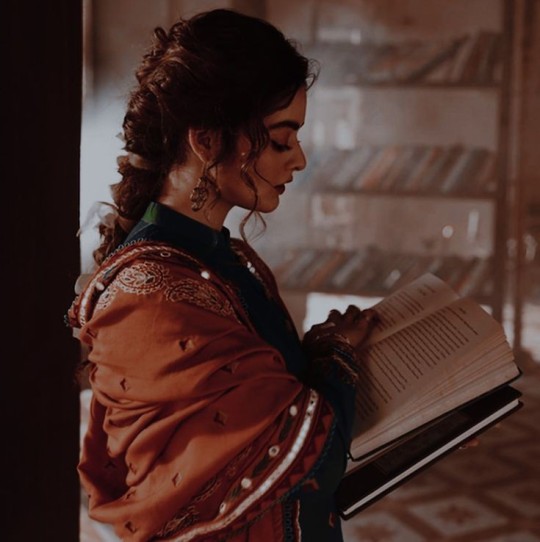

avantika vandanapu icons | like or reblog if you save

#avantika#Avantika Vandanapu#Avantika Vandanapu icons#twitter icons#twitter layouts#icons#female icons#female#actress icons#actress#site model icons#brunette icons#brown women#brown actress#south asian women#south asian#mean girls#mean girls 2024#mean girls musical#mean girls karen

133 notes

·

View notes

Text

📸 | Simone Ashley on Instagram: “A week off in my favourite place 🍓☀️”

#simone ashley#bridgerton#kate sharma#instagram stories#myla#bridgerton cast#daily woc#wifesource#femalestunning#femaledaily#wonderfulwoc#south asian women#dailykanthony#dailywoc#britishladiesdaily#southasiansource#flawlesscelebs#ladiesblr#dailybridgerton#flawlessbeautyqueens#disney the little mermaid

175 notes

·

View notes

Text

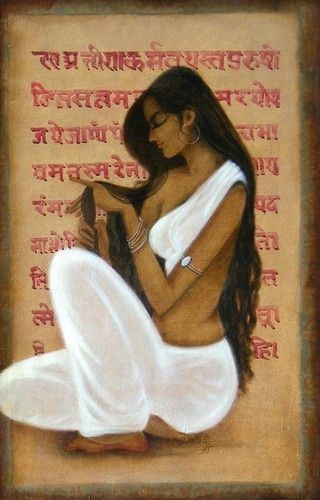

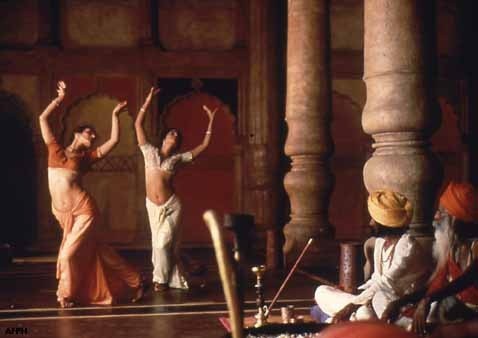

Divine feminine

All the artists are mentioned here ✨

#indian woman#south asian women#art forms#indian art#divine feminine#desiblr#desi tag#desi tumblr#desi culture#desi academia#indian academia#desi aesthetic#indian aesthetic

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Reminder that in 1969 21 Punjabi women were fed radioactive chapattis.

A van would pull up outside their homes giving them for free.

They contained radioactive salts.

None of them knew about it.

No consent was given.

Although in the 90's, the Medical Research Council in the UK objected to victims speaking out about it.

Insisting consent was given and they even have a Gujurati speaker to translate.

... Despite the victims being Punjabi women who didn't speak Gujurati.

These chapattis were given with the promise of giving health benefits to Punjabi women going to the doctors for things like migraines.

But no... Keep telling me how our government cares about us.

There's a documentary about it called Deadly Experiments, and I've linked the article about a victim speaking out about it.

https://www.indiatoday.in/magazine/international/story/19950815-film-on-medical-experiment-on-punjabi-women-causes-stir-807630-1995-08-14

It's truly despicable but ultimately not suprising.

#Radioactive chapatis#Punjabi#Indian#indian food#British#England#south asian women#people of color#women of color#Ethics#Research ethics#England news

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

#quotes#south asian aesthetic#south asian academia#impostor syndrome#literature#desi aesthetic#desicore#book quotes#desi#desiblr#desi tag#kajol#brown aesthetic#brown women#women#desi academia#desi women#south asian women#orange aesthetic

282 notes

·

View notes

Text

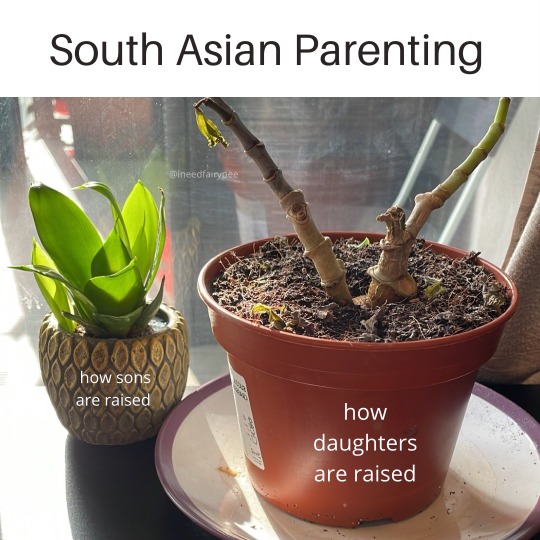

Loving your daughter? What’s that?

#south asian#desi culture#desiblr#desi memes#desi things#plant memes#eldest daughter#indian memes#indian#indian things#indian women#indian culture#indian girls#desi girl#desi stuff#asianwomen#south asian women#meme maker#memes#oc meme#oc#oc memes#ineedfairypee#fairypeememes#i need fairy pee

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

I just got out of an engagement and honestly, I feel free. Ladies, always trust your instincts before it's too late. Shitty men exist in many forms. Your safety and wellbeing comes first. I pray you all have friends and family around you that you can depend on who support you because that helps a lot, but only you can make those big decisions.

#personal#women#toxic men#marriage#i was about to enter a bad potentially abusive situation within a month#but i'm glad it's over#south asian women

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yasmeen Ghauri

Chanel Haute Couture

Spring Summer 1996

By Karl Lagerfeld

Hat by Philip Treacy

#yasmeen ghauri#chanel#karl lagerfeld#philip treacy#1996#haute couture#spring summer#paris#1990s fashion#gifs#gif#fashion gifs#south asian women#fashion shows#supermodelo

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

My sister has already started being bullied by the white kids in her class for having body hair.

She's in 5th Grade.

Growing up as a brown girl, I had the same experiences with being ridiculed for dark body hair - on my legs, arms, face. I was emasculated by my peers and started over performing femininity. I began shaving behind my mamás back as soon as I started Middle School. It left me with scars from where I had a shaky hand and slipped, and I didn't know how to do it properly.

I bled to be "normal" by their standards.

From my trauma, I've been unable to shave in over a year. Now, I'm making the conscious choice to leave my body hair and embrace it - not for myself, but for my sister and for all the small brown girls who share our experience.

I'm still feminine and "normal" with body hair. It's beautiful and natural, thick and dark.

Let's change the standards, together.

#brown girl#brown woman#north african women#brown girls#brown women#latinas#body hair#woc#woc experience#'normalise body hair' EVEN WHEN ITS NOT ON WHITE WOMEN#'normalise body hair' EVEN WHEN ITS DARK AND THICK#self love#woc self love#brown self love#protect our brown girls#protect brown girls#protect girls of color#south asian women#imazighen women#turkish women#MENA women#middle eastern women#desi women

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oil painting study

o(* ̄▽ ̄*)ブ

Nagavalli the OG

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

So a while back I was at an art museum and I saw a piece by a Pakistani woman, Naiza Khan, from this collection and I wrote down her name so I could look her up later and I really wanted to share what I found because her works are really cool. The museum I went to wrote about the piece that it was ambiguous whether the sculpture was meant to be viewed as restrictive or protective, and I liked that angle a lot. This page I posted the link to expands upon that even further and I wanted to share some of my favorite passages:

“In writing about her installation piece The Crossing in which suits of armor created around the female shape set sail in a wooden boat, Naiza drew attention to the year in which she made the installation—1429 Zil-Hajj, an Islamic echo of the Christian calendar’s year 1429 in which Joan of Arc led the French army to victory in the Battle of Orleans. In Pakistan, 1429 Zil-Hajj started during the 40 day mourning period for Benazir Bhutto—like Joan of Arc, a female leader who polarized opinion and died brutally, reviled by some, sanctified by others. The empty suits of armor speak to the history of both women, and force us to ask in which calendar we’re living—15th century or 21st?” (Page 8, Kamila Shamsie)

“… the fact remains that many of the armored pieces are, as Naiza puts it ‘designed to fit the imagination rather than the body.” (Page 10, Kamila Shamsie)

“Those gilded wings might be armored, but the real threat to them comes not from outward attack but from their own forgetful nature. When dreams or imagination descend, or cross over, into another space they are in danger of losing part of themselves.” (Page 10, Kamila Shamsie)

“Her turn to the hard and unyielding metal bodily implements, which include charged objects such as chastity belts, metal corsets, and lingerie made with steel, suggests that the tension between the demands of the social order, and the intractability of the body has sharpened considerably in her recent work.” (Page 12, Iftikhar Dadi)

“What is the possible relationship between obsolete European implements that seek to shape and control the female body, and modern Islamic legal, social, and ethical injunctions for women? Is modern, scripturalist Islam simply being equated with medieval European repression, torture, or confinement? Or, as the reuse of such devices by S & M, bondage and other subcultures in the west suggests, have these devices today primarily acquired the aura of a transgressive fetish?” (Page 12, Iftikhar Dadi)

“Naiza’s work demonstrates that freedom for women is not a simple matter of transgressing or overthrowing repressive social mores, as the very delineation of what is possible to accomplish as an agent emerges within the discursive constraints of the social order.” (Page 19, Iftikhar Dadi)

“Naiza’s work insistently reminds us of this paradox of subjectivation. In order for the voice and the body of the woman to emerge into public space from a condition of invisibility and subalternaity, its presence must be recognized and shaped by discursive norms.” (Page 20, Iftikhar Dadi)

A quote from Naiza herself reads: “I made some images in my little book in July last year [2006]. These were drawings of “bullet proof vests.” I was intrigued by them, and felt they needed to be made in metal. At the same time they felt like something very soft, close to the body, like fabric… The idea of trapping and protection comes together in these pieces. An ambiguous thought, not sure where one idea stops and the other begins… something so prevalent in our society.” (Page 21, Naiza Khan)

“The welding points on the metal armatures are further allegorized as Heavenly Ornaments, suggesting that the terrible beauty of the violent forging of the metal joint is a necessary accomplice for subjective expression. The works in metal do appear to offer a choice—the ability to wear them or discard them at will. But this choice is essentially an impossible one, in that it is situated between the inarticulate, excessive, and private body, and the normative female body that is increasingly public and visible but forged by discursive norms that allow it to speak only by simultaneously working both violence and protection upon its bodily excess.” (Page 23, Iftikhar Dadi)

I encourage you to read the whole thing, because there’s a lot more discussion of the politics of her pieces, both in terms of feminism and Islam, and about how the artistic choice of her refusal to showcase head coverings (and, to a lesser extent, western beauty standards as well) in her physical works (while addressing them in written works instead) is symbolic. I really like the idea of the clothing being stuck between protecting you and harming you, showing you off but in a consumable way, and how she touches on the false perception of the choice that we have in the matter. She also has some other really cool works shown elsewhere on her website that aren’t part of this set (lots of watercolor!), some of which seem to be inspired by living conditions of people in Pakistan, the ocean, or South Asian history. She also has an instagram if anyone is still using that and wants to check out more of her work.

#women#women in art#women’s art#pakistan#islam#muslim women#muslim artists#radfem#radical feminism#south asia#south asian women#pakistani art#naiza khan

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

"So playing a three-dimensional immigrant mom has always been on my bucket list. To portray some of what we deal with, our struggles, what we left behind, where we’re going, the sense of isolation, the sense of relief, the sense of opportunity, the sense of joy, of being able to give your kid what you didn’t have — I mean, everything! It’s a very intensely personal journey. When you have an opportunity to see yourself reflected and represented accurately in media, that can make you the hero of your own story and take you from the sidelines into the center."

#women in media#nalini vishwakumar#never have i ever#immigrant parents#immigrant moms#south asian women#motherhood#motherhood in the media#tv moms

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Finally told my uncle (who said to my father that he shouldn't let me wear t-shirt and pants at home, but ethnic clothes) that he shouldn't have a say in my life, that I won't let the "man"in the house to meddle in my life, pointing the finger at him. It was so satisfying seeing his face of astonishment and trying to say it was wrong and not being able to speak cause I won't let him. Sisters today feminism wan a battle at a brown household.

#brown household#Brown experience#South Asian man#Toxic man#Misogyny#Gaslighting#Feminism#Patriarchy#Immigrant family#Fuck that I hate that man since I can remember#He really has this megalomaniac behavior#For him he has moral high ground about everything religion social and political issues#When he is just dirt#Hate man specially brown man#Brown girl#brown girls#Desi girls problems#south asian women#The older daughter

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gender, Sexuality, and Lesbian Organizing in 80s Delhi

Selection from “Rescaling Transnational “Queerdom”: Lesbian and “Lesbian” Identitary-Positionalities in Delhi in the 1980s,” by Paola Bacchetta, in Antipode Special Issue, "Queer Patriarchies, Queer Racisms, International", Vol. 34, No. 5, November 2002.

The first half of this selection covers political and social developments in India in the 80s, particularly focusing on shifts in gender and sexuality. The second half looks at the emergence of lesbianism as a topic in national media, starting with reports on lesbian (and trans male) suicides and marriages, and then moves to the formation of early lesbian and “lesbian” groups. The author uses “lesbian” in quotations “to refer to women who love women and do not identify with the term lesbian, and lesbian to signify those who do.”

Delhi: The Setting

Das (1990) has remarked that India‘s 1980s are characterized by "intense uncertainties,” “fundamental changes in society and polity," and "an escalation of violence." Historically, gender and sexuality have been central to sociopolitical conflicts in India (Chatterjee 1994; Nandy 1983; Sinha 1997) as elsewhere, and this period is no exception. To understand this aspect of the 1980s, it will be necessary to backtrack to the previous decade, at least, and to shift across scales from national to transnational to local.

Perhaps the most marking national political event of the 1970s was the State of Emergency (1975 – 1977) that Prime Minister Indira Gandhi of the Congress Party called. Fearing her loss of upcoming elections to growing opposition, she was able to use Emergency to censor and imprison oppositional social actors, left and right. After Emergency, a right-wing Hindu nationalist party defeated her center-left Congress Party to win state power (1977 – 1979); Congress was then re-elected in 1979. Hindu nationalists propose a Hindu nation-state wherein non-Hindu Indians (especially Muslims, but also Buddhists, Christians, Jains, etc) are to be "converted" or eliminated from the citizen-body, and they prescribe polarized models for normative gender and sexuality. Having tasted power in the 1970s, Hindu nationalists increasingly mobilized for electoral purposes, an effort that culminated in the April 1998 election of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) to state power.

For the lesbians and "lesbians" discussed in this essay, the 1970s marks the rise of the current wave of the Indian Women‘s Movement‘s (IWM). Although struggles by and for women have a very long history in India, and this wave of the movement was well in force prior to 1975, as Ray (1999) points out, that year it was given increasing legitimacy and publicity because of the "decade for women" called for by one of the globe‘s hot sites of power, the United Nations. In urban sites throughout India, including Delhi, women‘s 1970s protests (in collective forms such as demonstrations, sit-ins, petitions, and the like) centered on dowry murders, rape, wife-battering, and gender-differential deprivation linked to poverty (Basu 1992; Ray 1999). Simultaneously, male directors in Bollywood ("Hollywood" in Bombay/Mumbai, the central site of popular Indian film production), in a new trend, began to produce revenge films centered on wronged female protagonists who retaliated against offending males. In so doing, they massively--albeit perhaps inadvertently--diffused models for women‘s individual revolt throughout parts of the national cultural scape.

In the 1980s, three national political issues became focal points for the production and massive media diffusion of right-wing representations of gender, sexuality, and religion and of counter-representations by women engaged in women‘s struggles and in movements against Hindu nationalism. The earliest was the Hindu nationalist campaign to demolish the Babri Masjid, a sixteenth-century mosque. Hindu nationalists claimed that the "Muslim invader" Barbar had razed a temple marking the Hindu god Rama‘s birthplace (Ramjanmabhoomi) to humiliate Hindu masculinity and had constructed his mosque, the Babri Masjid, on the temple‘s ruins. For Hindu nationalists, the resurrection of Hindu manhood required a reversal: the demolition of the mosque-phallus and the reconstruction of the temple (Basu 1993; Bacchetta 1999, 2000). They carried out a very high-profile campaign against the mosque for a decade. Then, in December 1992, during a mass demonstration they had organized on the site, Hindu nationalists succeeded in illegally battering the mosque to the ground. Those who participated were mainly men, but some Hindu nationalist women were also among them (Bacchetta 1993,1999; Basu 1993, 1999; Sarkar 1993). Throughout this conflict, women “figured as crucial markers of identity--of nation, community, caste group and religious group” (Chhachhi 1994). Following the mosque demolition, Hindu nationalists orchestrated riots between some sectors of Hindus and Muslims near the demolition site and in a few urban centers across India. In these actions, Hindu nationalists moved to hyper-protect Hindu women‘s bodies while sexually violating Muslim women (Bacchetta 1994, 2000).

Another national political struggle that provoked shifts in gender and sexuality in the 1980s was the challenge to religiously based legal rights (Engineer 1987). This began in 1985 when Shah Bano, a 76-year-old Muslim divorcee seeking maintenance rights, publicly challenged Muslim personal law. In India, personal laws (for Hindus, Muslims, etc) constitute a system of religious laws governing civil matters (marriage, divorce, inheritance, adoption, etc) that are parallel to all other branches of law that uniformly govern Indian citizens regardless of their faith. For many Indian feminists, all the systems of personal laws are detrimental to women, for they reify male familial and religious community control over women. Hindu nationalists used the Shah Bano case to represent Muslim males as more-oppressive-to-women-than-we and proposed a uniform civil code based in Hindu law to Hinduize India‘s legal system. Feminists engaged in a vigorous and interesting debate: some advocated a secular uniform civil code; others recommended preserving, but internally reforming, personal laws. Eventually the Shah Bano case reaffirmed misogynarchal control of women by their "religious community" with the passage of the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Bill in 1986.

A second major issue of the 1980s was the 1985 sati (widowed wife entering the funeral pyre of the dead husband) of a young widow, Roop Kanwar. It sparked further feminist-versus-Hindu nationalist polarizations around Hindu women‘s relation to husband, family, "religious community," and nation. While sati is an extremely complicated issue with a sordid history in colonialism and is subject to elaborate debates,[4] in general feminists maintained that Kanwar had been drugged and forced to die, while Hindu nationalists defended the practice.

Perhaps the most significant event of the 1970s and 1980s for the lesbians and “lesbians" discussed herein is the fact that, at this time, lesbianism itself began to appear in the national mediascape. The first reports were about lesbian suicides and marriages. Lesbian suicide appeared first, in 1979, when partners Jyotsna and Jayashree, after forced marriages to men, jumped in front of a train together (ABVA 1991:70). On June 29, 1980, college students Mallika and Lalitambika, both aged 20, tied themselves together and leaped into a channel, but were "saved" against their will (ABVA 1991:70). In October 1988, Gita Darji and Kishori Shah, 24-year-old nurses facing separation by Gita‘s husband, hanged themselves together (India Today 1988). In August 1990, Vandana Cibbal, aged 22, shot her lover Simmi Kapoor, aged 21, and then shot herself, one month before Simmi‘s scheduled forced marriage to a man (Thakur 1990:33). The press produced these women as tragic, dangerous, or simply unintelligible.

Reporting on lesbian marriages began later (Cath 1996). Partners were represented in three modes: as asexual friends; as uppity masculine-identified woman with uppity feminine-identified woman; and as transsexual with otherwise-normative woman. A first example is of village teachers Aruna Sombhai Jaisinghbhai Gohil, aged 31, and Sudha Amarsinh Mohansinh Ratanwadia, aged 29. They entered maitri karar (friendship agreement) before a notary public in 1987 after nine years together (ABVA 1991:69). The media was not unfavorable; some journalists seemed to presume the bond was asexual and thus in compliance with middle-class asexual/hetero norms. In contrast, in the second model are 28-year-old police constables Leela Namdeo, a widow,and Urmila Shrivastav, who, as an adult, rejected the man to whom her marriage had been arranged at age 3. A Hindu priest performed their December 1987 marriage ceremony in a Hindu temple in their parents‘ presence (ABVA 1991:67-68; India Abroad 1993). Following disapproving press, they were fired and banned from their town. A third example is the December 1989 marriage of Tarunlata, a female-to-male transsexual aged 33, with Lila Chanda, aged 23 (ABVA 1991:36). Lila‘s father got their marriage annulled under Indian Penal Code 377 (an Indian antisodomy law imposed under British colonial law and never repealed).

This mediascape attention had multiple effects. For some, the public attention constituted a form of violence. Lesbianism was now constituted as the negative supplement, in the Derridian (1976:244) sense, to women‘s proper identities and as a site of nationalism renegotiations. Indeed, some of the reporting contained a recurring theme that lesbianism was not Indian, but rather a British-imported perversion. A number of lesbians and "lesbians" resisted xenophobiclesbophobic attempts to white-out lesbianism by reterritorializing lesbianism (as Indian) in letters to the editors. At the same time, some lesbians welcomed the mediascape opening of the topic because it allowed them to gage their family‘s, community‘s, and wider society‘s views on the subject.

By the 1980s, public--especially middle-class--debate was increasingly polarized around sexuality. At that time, several shifts occurred. For one thing, some parts of the mainstream press began to discuss anormative heterosexuality and pornography and to adjoin these to homosexuality, all in opposition to normative, national, proper sexuality. For example, the popular magazine Sunday, in an issue entitled “Sex and the Urban Indian," produced hetero “unchecked excesses” and designated them, too, as "not Indian”: pornography, prostitution, and extramarital sex (Sunday1992). The issue contained a photo including an activist pamphlet, Less Than Gay: A Citizens’ Report on the Status of Homosexuality in India (1991) by AIDS Bhedbhav Virodhi Andolan (ABVA — AIDS Antidiscrimination Movement) as an example of pornographic literature, and the editors refused to publish protest letters (Bacchetta et al 1992). This outpouring of condemnatory discourse was countered by much dissent. For example, several renowned actors and writers and a religious figure, the Dalai Lama, publicly supported homosexuality. And some Hijiras (male-to-female transsexuals and/or transvestites [see Cohen 1995; Kumar 1993; Nanda 1993]) were suddenly given roles in Bollywood films such as Daayra, Darmiyaan, and Tamanna (Chawda 1996). Ultimately, one can ask the question of to what desires this overall outpouring of discourse--for those who expressed pro-queer positions and those who imagined themselves as the sexuality police alike--corresponded during the period.

During these 1980s debates, some middle-class lesbians and "lesbians" in IWM networks began autonomous discussions. They recognized each other through what Valentine (1996:154) terms "lesbian manners and styles." These sometimes included cues such as single status (not always; many are married) and a certain psychic and corporal sensibility. The middle-class urban lesbians and "lesbians" discussed in this essay often met in each other‘s homes. However, only some homes, or parts of home, where the heterofamilial could be avoided were appropriate: apartments and rooms of those living alone, or bedrooms of those who did not. The kitchen in the middle-class heterofamilial home in Delhi (unlike the kitchen of Kitchen Table Press) is a workspace trafficked by male and female servants and female family members; it is not a gathering site, and was therefore not an option.

From these early conversations was born the Delhi Group (the term “lesbian," a subject of disagreement, is notably absent). Group discussion topics included: pressure to heterosexually marry; familial and societal lesbophobia; economic independence; countering antilesbian media; relations to the IWM; and heterosexist laws. Soon there was a split over strategies (remain a discussion group? engage in projects? mobilize a rights campaign? visibility or not?). Some founding members of the Delhi Group formed Sakhi (a term habitually translated from Hindi as "best woman friend of a woman," but which Thadani [1996] redefined as female friend, lover, erotic relation between equals). Two lesbians remained simultaneously in both groups. Sakhi created India‘s first lesbian archives and published the first out lesbian statement (in 1990) in the gay magazine Bombay Dost (Bombay Friend).

Two lesbians--one from Sakhi and the other from the Delhi Group--were among the cofounders of the 1980s Red Rose Rendezvous Group, which was open to lesbians, gays, bisexuals, transgendered people, and transsexual people. The Red Rose group was so named for its meetings around a red rose at India Café in New Delhi‘s center, the large terrace of which dominates colonial-constructed Connaught Place. India Café was chosen because of its central location and its openness to many different classes of people. Early participants in the group were mainly middle-class gay men. Eventually, expansion efforts drew some lower-class participants, again primarily gay men. Within a year, meetings moved to a public park, another multiclassed site, contingent to the elite India International Center (IIC).[5]

[...]

Throughout the 1980s another cluster, "lesbians" who often worked in bastis (urban slums), self-identified as single women (see below). One single-woman “lesbian" participated in the Delhi Group.

These 1980s lesbian and “lesbian" emergences at multiple simultaneous scales undo the West-centric private-versus-public dichotomy, including its feminist incarnation as women-private/men-public. The multiple emergences also confirm and undermine Indian sociospatial organization as a home-to-world continuum (Kaviraj 1997); lesbians and "lesbians" crack it open to identify and invest deheterosexualizable and lesbianizable/"lesbianizable" sites throughout.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

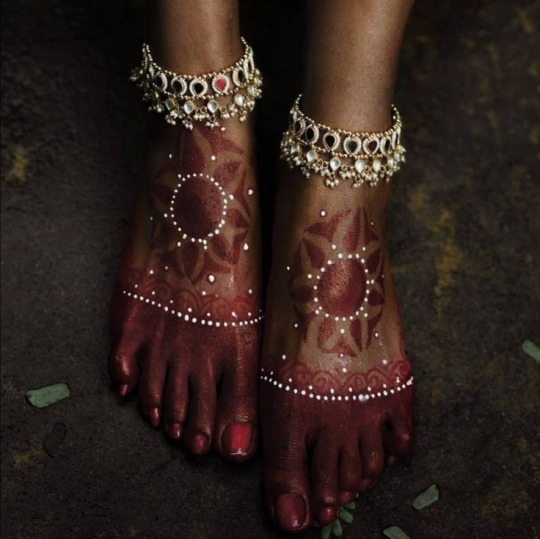

classic red

#south asian moodboard#south asian aesthetic#south asian#desi aesthetic#desicore#desi#desiblr#desi tag#desi moodboard#red aesthetic#indian aesthetic#indianwoman#south asian women#brown women#desi culture#desi women

222 notes

·

View notes

Text

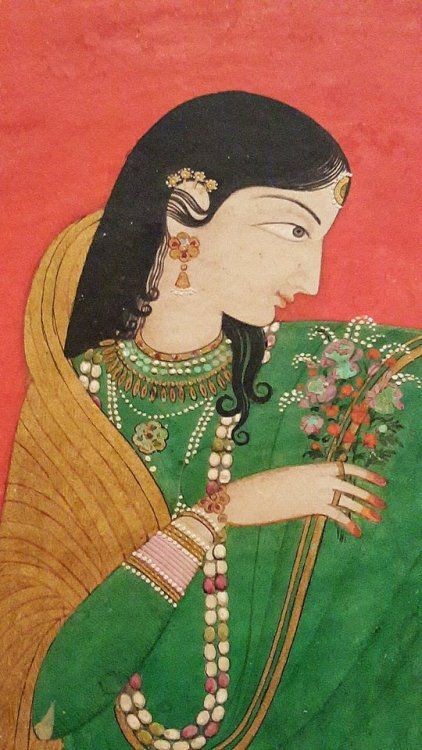

ladies, remember to follow the 16 steps of mughal self-adornment and self-care

According to Abul Fazl there are sixteen constituents by which a woman is adorned. Bathing, anointing with oil, riding the hair, decking the crown of her head with jewels, anointing with sandalwood unguent, wearing various kind of dresses, sectarial marks of caste and often decked with pearls and golden ornaments, tinting with lampblack like collyrium, wearing ear rings, adorning with nose rings of pearls and gold, wearing ornaments round the neck, decking with garlands of flowers or pearls, staining the hands, eating pan and finally the artfulness. (Fazl ,1977)

Dey, Sumita. “Fashion, Attire and Mughal Women: A Story Behind the

Purdah.” The Echo, vol. 1, no. 3, 2013, p 106, https://www.thecho.in/files/sumita-dy.pdf.

25 notes

·

View notes