#Subcultural osmosis

Text

I was griping to my wife about some of the odd details that show up in virtually every Holmes adaptation via, I guess, pop cultural osmosis? Even though they're at best exaggerations of details and at worst literally not in there at all. (E.g. every supporting character getting rolled into Lestrade, the idea that Toby is Holmes's dog, Evil Mycroft...) We eventually arrived at the conclusion that it was the biggest and most mainstream case of "fanon", which is kind of wild, since I'd actually say the majority of this stuff is NOT made by people who are in "the Sherlock Holmes fandom" or fandom subculture generally. But I guess some of these adaptational pitfalls are ubiquitous ways of flattening the source material, and not the product of any particular fan community.

#also re the lestrade thing I guess it's fair via the law of conservation of characters or w.e. I just find it a bit repetitive#esp when he's like getting exaggerated into their buddy

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

on demonic society: culture

long post. buckle up

general questions

if everyone is freely allowed to steal and loot in a lawless world, how are shops still operating?

it may be a “lawless” world but that doesn’t mean its inhabitants are completely rabid. most of them are former humans stuck in the societal grooves of their past life anyways, so there’s always at least some money in circulation out of a sense of obligation. it’s a lawless world for shop owners too so who’s stopping them from hitting thieves with the .38 special. on the flip side some shops are just running for the love of the game babey

cultural values (quick overview version)

hedonism is awesome

i got mine, fuck you

despite everything they love a tight-knit community

ur completely bitchmade if you cave to what others expect of you

your lineage means jack shit

naming conventions

draw upon the macabre, the evil and the esoteric for names, as well as variants on lucifer (ex. lucille, vice, maljean, and venom)

family structure

biological family ties are extremely loose, so most don’t even end up living with their children (who instead look for that found family type beat). the most common structure is in groups of 4 or 5 with equally shared responsibilities. groups are usually formed out of a need to stick together, plus combined income and so on. younger demons will live with their parents for a brief period of time, and since there is no central education system they must learn life essentials via osmosis.

non-hereditary demons may end up reuniting with their family from their previous life or choosing to start fresh, most choosing the latter. some are also known to move into pre-existing groups for their first few years down under.

angel relationship/cohabitation

aren’t foaming at the mouth to obliterate their divine counterparts like the angels are. there’s a sizable number of them down under since a bunch of angels defected when lucifer fell, and afterwards a lot have been exiled from utopia. most want to hide their angelic features or not make a big deal out of them, since opinions on angels differ wildly from person to person.

cultural divides

wife wars

small sect of the population that thinks hellion society was at its best when [REDACTED] was lucifer’s wife and want to “reject modernity, return to the green top” as they say

anti-angel sentiment

some people are bigoted idk what to tell u. they form a sort of "square vs rectangle" idea with the fundies, not all anti-angel people are fundies but every fundie is anti-angel.

the fundies

they’re their own cultural divide. basically militant extremists that violently oppose technological and cultural progress (trans-humanism especially) because it strays father from the “peak” of hellion civilization when you could easily kill angels with the flick of your wrist and eat the drywall with no consequences (and lucy had NO wife). they want to send your ass back to the stone age so bad

the doomsday cultists

…will be discussed at a later date

niche subcultures

homebrew

freaky little basement rats that wanna hurt you so bad (with their own homemade atrocities of course). put that basement dwelling to work by making pipe bombs, flashbangs, hand grenades and bootleg spell charms (lab-synthesized magic in a marble-like capsule) to use in…street fights mostly. they make up a good percent of both the buying and selling portion of the weapons black market. the especially weird ones are currently innovating the homebrew meta by adding canisters of Unspecified Chemicals to their creations. and anthrax spores that too

magicians

dnd nerd club that wants to revive the dead art of magic (they can’t on a wide scale unfortunately, more on magic here) but they can sure try. think that spell charms are a farce and they’re so above using them guys trust me

fashion

the most common aesthetic seen down under is largely 2000s punk/scene inspired; mostly blacks, neon accents, funky accessories, the works. other popular styles include neo-military, proto-military, victorian, oddcore, jester/clown, futuristic, delinquent, and archaic. NAGAJAM is a popular designer brand that falls under the futuristic category.

makeup isn't stigmatized and is widely used by the public in smaller amounts. for most it’s only really used to accent features or pull attention to their facial markings/ drawing on the appearance of markings, but some are dedicated to creating bright and angular looks.

angelpunk counterculture

a notable subset have adopted the fashion and aesthetics of their angelic counterparts, in part to spite them. angel-like features and clothing are viewed as radical/punk, since it’s interpreted as them ‘wearing the skin’ of those who want them dead.

emeralds

culturally significant stone. fell out of lucifer’s crown when he was cast out of heaven and struck with a sword by the archangel michael. symbolizes pride, greed, and hellion nationalism. commonly paired with rubies in jewelry.

food

my stummy hurts 🥺 (eats a meal’s worth of goods that can’t even be classified as food when exported out of the United States)

mmm i love heavily processed foods yum

i eat-a the onion like an apple haha

anything sour or acidic is a staple of their food culture. green apples, onions, citrus fruits and the like are very common in native dishes. get ready for canker sores babey

a lotta stuff is heavily salted/preserved since depending on where you live electricity is not a constant

very meat-centric, mostly chicken since they’re fairly inexpensive to raise down under

they can and will drink petrol like it's orange juice

the thing about cans

energy drink cans (monster in particular) are extremely valuable down under. they don’t have the licensing to sell them there so the only way you can get one firsthand is traveling to the overworld to get one (which nobody really wants to do) so they’re automatically quite rare and considered a commodity. most don’t actually drink it but keep it for the can which can essentially act as a secondary currency in some places. due to their status, people will want to flex them in outlandish ways. you’ll see people making candles with theirs and selling the cut-off tops or some completely goofy shit

pop tabs collected from these cans are also a popular accessory, strung into necklaces, earrings, made into chains, sewn on pants as accents, etc. colorful ones are the most sought after.

the old gods

killed by lucifer a long time ago during his deicide era but still permeate through pop culture. cosmic horror and kaiju are popular genres throughout multiple mediums.

one thing they have in common with the great upstairs is that they both worship long-dead idols from years past, though not to the same extent the angels do with the Old Divines. they’re not petrifying their corpses and hanging them up for all to see whilst deifying them post-mortem like the angels are but i think it would be quirky if they did

#this is almost a 1:1 mirror of the notes i have on my phone so this one’s been cookin for a while#loreposting#oubliette metro

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

You know like, huge machines and like vehicles and aircrafts really do have a fuckload of horror potential I think (or maybe it's just me who is afraid of huge large fast loud machines that have massive destructive potential and are and can be used to harm people??) I've seen lots of movies with stuff like this but so many come off kinda goofy, and like... idk? Maybe it's not as universal as I thought it was? Like I think of like huge building complexes where everything runs on one system like lights and lifts and esculators and conveyer belts and screens and sound systems and automatic doors and security and like... thats terrifying to me?

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

I love Jedi influencing clone culture and just think of the idea of clones picking up specific traits from their generals so each battalion becomes their own little subculture within clone culture

Ponds is shown to be compassionate and care about the lives of civilians (he wants to share his battalion’s rations with Twi’Lek villagers) in the same eps as Mace saving his men.

Cody and Obi-Wan are both level-headed tacticians with associations to many reckless idiots, which in turns means they are reckless too. (Cody going along Rex’s “roger roger” plan, just Obi-Wan and Anakin and Ahsoka in general.)

Padmé literally tells Anakin that it’s probably his fault Rex rushes into things.

Kit’s battalion swims. (There are so many amphibian Jedi, there has to be flying species among them too, right? Headcanon that the battalions under flying Generals were the ones who got the jetpacks first).

What I’m saying is: yes. I love it. If you put a bunch of - admittedly highly mature, intelligent and competent - very, very young men under an authority figure who wants to see them express themselves and be the best of the best, you can bet quite a few of them will try to emulate said authority figure.

Just a progressive osmosis between the Generals and their troops, to the point you’re not even sure who influenced who anymore.

781 notes

·

View notes

Text

Woomycanons

Most Turf War competitors have a set group of friends they compete with, perhaps switching some people out if their group is bigger than four and/or more flexible. This especially holds true for League and Ranked. Either way, with Turf Wars, there’s no rules for who you need to go in with and people will go in alone, but doing so 24/7 is a bit odd socially. It’s more of a newbie thing or something you do on a whim/if you don’t want to wait. Those who never go with at least one other person they know are seen as loners - either willingly or unwillingly

Fashion means a lot to inklings, especially the youth. Practically everyone keeps up with the trends or finds some fresh subculture. Even with uniforms, many students will find some way to customize their outfits - hair accessories, earrings, you know. Certain friend groups will wear matching accessories - for example, three girls wearing all wearing their hair up in pink scrunchies - as a symbol of their bond.

Likewise, friendship bracelets and similar matching-type accessories are common and beloved! Inklings and Octolings alike enjoy swapping little gifts.

Coming from a culture of those without the “upper hand”, Octolings (especially those who are older or have not gone to the surface) do not have the same infatuation with style. They like nice things, of course, but they have an easier time embracing oddities and unconventional styles. I mean really unconventional, especially with some cultural osmosis with the salmonids. I mean, some elites want what they want and have higher standards, but the populace loves mismatch socks and hand me downs and thrifty put-together outfits.

28 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey, why do you think people get upset (especially purists) with the concept of Johnlock when it's been here for ages? I love the thrilling impulsive disordered way Sherlock thinks and acts (like my ADHD, OCD, and other mental disorders which I headcanon Sherlock to have.) alongside his nurturing and supportive Boswell (like my fiancé). They're flirty, fun, and affectionate with their jokes and laughs with each other throughout their mysteries, and that comforts me. Canon is damned and I don't care what Conan's opinions are if it makes me happy. Why are people so sour, salty, and act like the idea of me writing fanfiction and buying fanart of my first ship at 12 (when I first read Sherlock from the public library with my nana a decade ago) is the worst thing in all of existence and ruins Sherlock Holmes? Am I the crazy one or is everyone else who's crazy? (Btw it's nice to see someone on Tumblr who loves the OG turn of the last century version Sherlock than the terrible show alongside Lupin and Raffles.)

Hi anon! I know you probably just asked this question to get me to respond about how it’s ridiculous that anyone would get that upset about a fictional ship, but this question got me thinking for a bit. I’m one of the most biased sources here (i’ve made posts about how i don’t tag John/Sherlock because it should be a given, etc.), but I’ll try to respond to this question with an honest and fair answer because there are a lot of factors as to why people get upset at John/Sherlock.

Below the cut I’ll talk about:

1. Cultural Osmosis

2. 19th Century Friendship

3. Distaste for Shipping

4. Homophobia

1. Cultural Osmosis

One of the reasons I think is most prevalent is that people who have never read or watched any Sherlock Holmes content assume because it’s so old and so popular that they’ve somehow absorbed enough of it through pop culture and references that they know what Sherlock is like via cultural osmosis. They know he’s deductive and doesn’t like people, so they assume he’s cold, always calculated, and the pinnacle of detective perfection. They know John is the narrator and Sherlock’s friend, so they just assume John is basic, boring, and so uninteresting that he’s barely in Sherlock’s social circle, but merely tags along with him. This vision of both of the characters is skewed so far from the canon that people either can’t fathom how you ship these two characters who in their minds are very incompatible, or the more common thing, people have a preconceived notion that you’re looking too much into it because nothing old and published can be gay.

(This kind of thing isn’t just exclusive to Sherlock, either. People will also gawk at the idea of Spock/Kirk from Star Trek TOS because they assume they know what TOS is without even watching it because they’ve seen the cultural impact of “beam me up, Scotty” and “live long and prosper.” They create a mental image of TOS that’s mostly full of their own assumptions, and gay subtext isn’t one of their expectations.)

2. 19th Century Friendship

Another reason is that historical male friendships are different than what the typical male friendship is now. In the 19th century, men were more open to showing affection for each other in strong ways. Photos from the century show male friend groups openly holding hands, arm in arm, and helping light each other’s cigarettes. Obviously a lot of men are shaking off ideas of “manliness” that limit the way they can express their platonic love to their friends, but there’s still a lot of men that won’t hold their best friend’s hands because “that’s just weird/that’s gay.” This is all a long-winded way of saying that, to some people, Sherlock and John are the pinnacle of close male friendship in the 19th century. They are the perfect show of platonic affection between men, something that some people look up to and aspire towards. To people who think of Sherlock and John as exclusively best friends, they may feel offended or baffled that anyone would try to “ruin” that friendship by making the two lovers. That’s why some people who are legitimate fans of Sherlock Holmes may take offense to the ship: they think it ruins the friendship between the characters.

3. Distaste for Shipping

It isn’t uncommon for fans of a series to have a distaste for shipping elements, especially for a series whose sole focus isn’t romance. Sherlock Holmes is in no way a romance, and some people feel that shipping shouldn’t be the focus of fandom content because the source material isn’t romantic. People who want to focus on mystery and suspense elements may believe that shipping ruins what fans should be focusing on and appreciating in the franchise. And they have some merit in thinking that shipping can ruin the focus of a franchise, because there are definitely some fandom subcultures out there that ignore important themes and messages in shows to instead focus on their ship. But, this is an over-generalization of any fandom, clearly.

The above reasons for someone disliking Sherlock/John are not malicious. They assume the person is well-intentioned but misguided. In the cultural osmosis example, the person just doesn’t understand the source material and thus doesn’t understand the ship. In the friendship example, the person just wants to see a male friendship that isn’t toxic, and mistakes the act of shipping for throwing away that interpretation entirely. In the distaste for shipping example, the person just wants to focus on the themes of Holmes and not the romantic subtext. However, saying that everyone who gets upset at shipping John/Sherlock is well-intentioned would be a lie.

4. Homophobia

There’s an obvious reason of—whether implicit or explicit—homophobia when some people get downright disgusted or outraged that someone would ship John/Sherlock. I don’t think it needs explanation as to what homophobia is, but Sherlock/John especially outrages people more than other gay ships because the characters are classic. Sherlock is known throughout the world, everyone knows his name even if they’ve never read any of the stories, and his iconography—smoking pipe, hat, and jacket—have become well-recognized. It makes ignorant people boil over when you say that this iconic character who has remarkable impact on the world may be gay, asexual, or transgender. They think that lgbtq identities are something taboo or something to be ignored. To them, lgbtq characters should be background noise at most. And vocalizing that you see John/Sherlock subtext in their interactions destroys that.

TL;DR: Some people may be upset by John/Sherlock because they don’t understand the source material, they think shipping destroys a friendship dynamic they liked, or they feel that shipping takes away from the story. Some people may be upset by John/Sherlock because of ignorance and homophobia.

24 notes

·

View notes

Note

wait is ratblr an actual term?

Ratblr or Rattumb - I’m not sure what the preferred term is for Rationalist!Tumblr but it is a thing that definitely exists and that I definitely interact with.

I love the weird divisions in that group. Like. Does simply knowing of the existence of rationalist tumblr make me a part of rationalist tumblr? Or am I rationalist adjacent since I’m not a rationalist? or AM I a rationalist because I believe it’s important to do things like update your assumptions and ask why I know what I know? Or am I rationalist adjacent adjacent because I’m not on LW but I’m also not even part of the sneerclub I just get *everything* second-hand from dash osmosis?

Anyway. I’m pretty peripheral to the whole thing but yeah, Ratblr is real.

And yes, I did unironically read and enjoy Harry Potter and the Methods of Rationality when it was publishing and there is in fact video evidence of me talking about how stoked I was for the end of the serial and how clever and tricky the cliffhanger before the final update was.

And yes, I did feel tremendously betrayed by the end of the serial to the extent that I actually went out and read about a third of The Sequences to try to see if there was something that I was missing about this whole thing.

And yes, I did get a third of the way into The Sequences before I realized that reinventing the wheel isn’t actually all that great and there was an awful dang lot of jargon being introduced and it was kind of funny how if this is how you looked at the world it became impossible to talk to people outside of this very specific subculture about your worldview and that might be kind of weirdly limiting and make it difficult to check your assumptions about the world and might create kind of an isolating information bubble or something.

And yes, I did google “Rationalist Movement” and come across RationalWiki and the page for Roko’s Basilisk and look I KNOW that it’s completely overblown when people talk about the movement but *god* it was such a fucking relief to see that somebody else who was familiar with this subculture was looking at it askance and was aware of some of the problems with how the sequences encourage certain thought patterns.

And yes, I did work with @reddragdiva and design the cover of Attack of the 50 Foot Blockchain and write lots of music reviews for his website and there are absolutely parts of rattumb that are very suspicious of me because I’m friendly with David and yes, I do understand that but no, I’m not going to stop being friends with David.

So I guess what I’m getting at is Rationalist!Tumblr probably doesn’t want me representing them but I’m a fairly decent representation of someone who stumbled into the rationalist movement in the wild and became disillusioned with the movement pretty quickly.

Rationalists are interesting and in theory I’ve got no beef with them but in practice I’m really really upset that there’s a constant exhortation to take things as charitably as possible that never seems to get extended to your ideological opponents because every time I try to do that thing sincerely it just ends up with someone from rationalist tumblr calling me a rape apologist or an ableist if I suggest that a con code of conduct might be a good thing.

178 notes

·

View notes

Text

So! Let’s talk about this Jedi Code for a minute.

From what I have absorbed through social osmosis (I’m not terribly familiar with much of the EU material), the original Jedi Code went like this:

Emotion, yet peace.

Ignorance, yet knowledge.

Passion, yet serenity.

Chaos, yet harmony.

Death, yet the Force.

But by the time of the prequel trilogy and the Clone Wars, the Code appears to have been changed to this:

There is no emotion, there is peace.

There is no ignorance, there is knowledge.

There is no passion, there is serenity.

There is no chaos, there is harmony.

There is no death, there is the Force.

Unfortunately, the way the Jedi Order amended the Code and were practicing it is in many ways similar to my own evangelical/Calvinist upbringing. Let me illustrate, one by one:

There is no emotion, there is peace.

This point I feel has already been well talked over, so I won’t belabor the point too much, but there’s definitely a deep problem when you systematically raise an entire order to fundamentally distrust their internal compass (because that’s how emotions often function).

It’s also the most destructive kind of self-fulfilling prophecy. Raising an entire subculture of people to be suspicious of emotion in the abstract leads to an environment where you can’t examine or interrogate your emotions. And, paradoxical as it may seem on the surface, a culture raised not to examine or interrogate their emotions (and whose primary way of dealing with them is to expel them -- I mean, ‘release them into the Force’) is a culture who will be up to its neck in self-deception, hypocrisy, and unacknowledged constant fear. On the other hand, a culture that is conditioned to be emotionally aware and intelligent is, paradoxically, in much less danger of actually being ruled by their emotions.

Trust me, I know a thing or two about being raised to deal with emotion by pushing it away in a religiously sanctioned manner. It does not lead to whole, healthy persons who are at peace.

There is no ignorance, there is knowledge.

This point holds more interest for me than it seems to hold for most people, so I wanna park here for a moment. You know what it sounds like to me? A fixation with certainty. Now, evangelicalism does not have a monopoly on certainty, but the form it takes in evangelicalism is what I have experience with. I also think it’s quite useful and instructive in examining where the Jedi went wrong.

In an ideology that prizes certainty, religious advancement is closely correlated with acquiring correct information and refuting incorrect propositions. By the time of the prequel trilogy and the Clone Wars, experimentation in using the Force was forbidden, or at the very least highly discouraged, at a systemic level. You do things one way because it’s the Right Way, and anything outside of the Right Way is automatically suspect and probably Bad. If the Right Way is painful or difficult for you, that’s because there’s something wrong with you, and it means that you need to work harder to conform.

For both the Jedi and evangelicalism as I knew it, actual curiosity and creativity are explicit threats. You don’t ask why we do things one way. You don’t ask what other ways there are of doing things. And you definitely don’t entertain the notion that a voice outside the approval of the order is capable of speaking truth.

Actually, I’m going to have to do the unthinkable, and give the edge to evangelicalism here. At least evangelicalism doesn't say that if you so much as start down a ‘wrong’ road, it defines you and you can never come back. But so far as the Jedi are concerned, you can’t even touch the Dark Side without becoming irrevocably consumed by evil.

There is no chaos, there is harmony.

Basically, in my opinion, the hypocrisy-slip is really showing here. The Force is wild -- if it really is ‘that which is between all things,’ then it’s just as present in the storms and high seas and exploding nebulae as it is in stationary rocks. I don’t think it’s possible to interact with the Force at all without inviting some amount of chaos. And that’s not even touching the fact that some amount of chaos is just inherent in being human.

Also, as a piano major, let me let y’all in on a little music theory secret: there is no such thing as music that has no dissonance, no sonic ‘chaos.’ You can’t even have chords, the basic building blocks of harmony, without some dissonance between the notes. Part of what constitutes harmony in music is an agreement between composer and listeners (and performer/s, I guess) as to how much chaos is acceptable before the music becomes meaningless noise.

What I’m saying is, you can’t have harmony, you can’t have music, without inviting chaos.

And, infuriatingly, I think they know this. Both Obi-Wan and Yoda in ANH both tell Luke that when you tap into the Force, it flows through you. So it really looks to me like what they’re really doing is denouncing anything they can’t control and calling it ‘chaos,’ while allowing contact with whatever they can control by calling it ‘harmony.’ That’s really what it’s all about for them, it’s about control.

And oh boy, do I know what it is to live under a religious order that pays lip service to internal harmony, but is actually all about control.

There is no death, there is the Force.

Well, I’ll give the Jedi this much: unlike evangelicalism, they don’t bring up their littluns to believe that someone who doesn’t accept their version of reality is damned to eternal torment.

However, there is a larger problem where you’re refusing to let people deal with death honestly. At some point when dealing with a loss, you’re expected to be able to say: “Yes, I will miss them, but they’ve gone to be with Jesus and they’re in a better place now.” You don’t really have any help in processing the fact that, whether or not the person you lost is in a ‘better place,’ you still had to figure out how to move forward with that loss. Especially not long-term.

And that’s what I’m so painfully reminded of when Yoda tells Anakin in ROTS not to mourn or miss those who have died, to rejoice that they’ve joined the Force. Recall that, at that point in Jedi history, nobody had EVER heard of someone dead remaining personally accessible to the living in any way. ‘Become one with the Force’ holds about as much meaning for people in the Star Wars universe as ‘gone to heaven’ holds for us.

And hey, again with me grudgingly giving an edge to evangelicalism: they allow you to have human ties! At the very least, they let you cry at the funeral. They let you say “I miss them.” But the Jedi, for all their bleating about ‘compassion for everyone,’ are very un-compassionate toward their own chickadees when it comes to letting them process death.

Now why did I choose to say all this?

There is, floating around some corners of the PT/CW Star Wars fandom at least on Tumblr, a certain idea that we should withhold sharp criticism of Jedi practices and beliefs because some aspects of Jedi-ness as shown in the films nominally resemble some points of Buddhism. In the eyes of those who hold such sentiments, criticism of Jedi ideology as practiced during the PT/CW reveals our true colors as white Christian imperialists unable to conceive of any other way of life being functional.

Well, being a degenerate and a daughter of slaves myself with no love of white Christian imperialism, and being a survivor of some very specific forms of religious abuse, let’s just say I know a super dysfunctional religious subculture when I see one. And the prequel-era Jedi definitely fit that bill.

In other words, there’s a little more going on with my critique of the Jedi than the ‘no attachment’ rule. It’s a whole system that’s gone wrong, and I’ve only just gotten started in talking about how.

#jedi critical#jedi order critical#jedi code#these people need some help#toxic religion#star wars#sw prequels#sw: tcw#clone wars#jedi ideology#when i said i was critical of the jedi this is what i meant

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

craft moms have this massive blogging subculture on the internet and you become really familiar with it if you turn to the internet for help making basically anything. if you read enough craft mom blogs you'll acquire craft mom energy through osmosis. it doesn't matter if you're not a woman or don't have kids. you'll become a craft mom

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

what does modern counterculture even look like? is there such a thing in this day and age when subcultural osmosis is happening every day and the most recent countercultures are all being absorbed into the mainstream culture?

#i might... be drunk and thinking a lot again#but like really... who is the culture and who is the counterculture?

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’ve almost finished reading Children of Dune now...

One thing I wonder about is ... where exactly do the Fremen get their food? The books occasionally mention foods the Fremen eat (meat, porridges and breads, coffee) but they never really describe their food system. There’s mention of “food gatherers” but I don’t think Arrakis could support large sedentary hunter-gatherer communities; those are unusual on Earth, and the non-sandworm/sandtrout biomass of Arrakis has to be pretty small and thinly spread. They eat the spice melange, is it a super-food on top of everything else? It is apparently quite conveniently versatile: they make from it cloth, plastic, paper, lamp oil, and it goes into all kinds of food-stuff. Shuloch has a small area of farmland around it, but it’s unusual. The explanation I like best is that they have a high-intensity indoor agriculture set-up inside the seitches, but it’s never mentioned.

This is something I notice generally about these books: a lot of significant things are actually left pretty vague. For instance, I have no clear idea what the Fremen religion looks like. It’s apparently got Islamic and East Asian elements, and they worship the sandworms (and used to give human sacrifices to them) and venerate Mua’dib, but I don’t get a clear idea of how all these elements fit together. I think it must be heterogeneous, because in one place the alam al-mythal is described in very transcendent-religion terms, but then the Jacurutans think you can kill people and bind them to be your slaves there (I wonder if this is a regional/class/subculture difference or if the Fremen just aren’t particularly concerned about inconsistencies in their religion). Similarly, I’ve got a vague idea of how Holtzmann shields shape combat, but I don’t have a clear idea of what a large battle in this universe actually looks like. I don’t think this vagueness is bad, but it doesn’t fit with the impression I got of the Dune books from fandom osmosis, and I find that a little interesting.

I feel some affection for Irulan. She’s a character who thinks in ways that remind me of how I think. She’s nerdy and kind of passive and her reaction to a man who catastrophically disrupted her life was to try to understand him. When Ghanima was pretending to make a bad decision out of desire for blood-vengeance I could just see her inwardly throwing up her hands in exasperation and going “THIS! FUCKING! FAMILY!”

I wonder to what extent everything outside the Bene Gesserit is a boy’s club? Are there female mentats, for instance? I hope there are (I vaguely want to write fanfiction with a female mentat character with a lot of inspiration from rationalist-adjacent tumblr women, but I have no idea what the plot would be). My reaction to the witch-courtesan-seducer archetype of female power is “OK, but what about the women who aren’t socially adept neurotypicals who are good at social gamesmanship?” I’m reminded of a conversation I had with a woman who said she liked informal power because it was historically a reserve of female power. My immediate thought was, yeah, that’s true, but where does that leave women who aren’t good at social games? I guess ideally other women would help and protect them because Sisterhood, but my impression is that actual socially awkward women are often treated pretty badly by other women.

My local public library is supposed to have a copy of God-Emperor of Dune, but it wasn’t there the last time I checked. I want to read it, it sounds like my kind of thing.

13 notes

·

View notes

Note

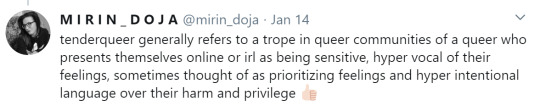

what is "tenderqueer"?

As someone who is decidedly Not Hip with the language used to describe subcultures, and only really knew about tenderqueer as a concept peripherally, I don’t wanna even try to claim to speak with any authority on the subject, but since you asked:

This is the best description I’ve been able to find of “tenderqueer” that doesn’t explicitly trash on the subculture, but to expand on this - basically, it’s an outgrowth of “self-care” and “soft” culture wherein specifically lgbt+ people use language relating to sensitivity and emotionalism as an aesthetic choice, sometimes with genuine emotion beneath the performance of those aesthetic choices, but sometimes very much without. There’s a Vice article from earlier this year that goes into it, and while I don’t agree with everything said here (there’s a lot of derision thrown at aesthetic choices associated with the tenderqueer subculture that I don’t personally think needs to be thrown out, but since this subculture is very aesthetically-oriented it’s bound to mix) I think it does a fairly good job of describing how tenderqueer has been identified as a performative and sometimes harmful trope. The point to highlight is really that it’s a subculture which puts an emphasis on sensitivity to the exclusion of being, like, actually sensitive, particularly to others’ experiences rather than your own.

Personally it’s not language I really use, and I think it’s largely been popularized on Twitter (and maybe TikTok? everything happens on TikTok, and I don’t pay attention to TikTok, so I don’t know these things). Tenderqueer isn’t something I associate with often, since I don’t really inhabit a lot of overtly LGBT+ spaces online or irl (which just kind of comes with being a general homebody and a queer person at a small school with a small lgbt population), but this is what I’ve gathered by cultural osmosis.

#ask#idk what to tag this with and also there's a good chance im wrong about things!! i dont get asked questions like this pretty much ever so.#uh. thanks for inquiring but also probably check with other people lol

0 notes

Text

I think Nightmare on Elm Street would have worked better, or just feel like less reactionary of sorts, if Krueger had been like a politician or some high powered profession as opposed to a janitor? It would also make more sense irt to how he was considered not guilty on technicality and that's why he was killed by the mob in the first place :p

#I have no love for the criminal justice system or state instituted death or imprisonment or anything and like#I just think there's potential with like exploring fear and danger and power#and unhelpful to complicit authorities#to like explore it properly in these movies#stuff and nonsense#subcultural osmosis

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

ESSAY: The Shōjo Heroine - Vaulting Geographic Barriers in Japan & Beyond

...The shōjo heroine, despite exemplifying fluid, nearly ephemeral identity, holds a multicultural allure seldom seen in Western works—one that allows her to straddle different cultures and continents while remaining quintessentially Japanese.

X-Posted at Apollon Ejournal

Within the dynamic realm of Japanese pop culture, the mediums of animanga have burgeoned into a fascinating contemporary phenomenon. What began as an obscure niche met with disparagement at best, dismissal at worst, has since then permeated markets on an international scale: from the cutesy craze of Pokemon to quintessential girl-power staples like Sailor Moon to critically-acclaimed masterpieces like Miyazaki's Spirited Away. The genre enjoys colorful permutations, raunchy or artistic, violent or thoughtful—sometimes in the same breath. Yet one of its most salient aspects is its recurrent use of young girls as both storytelling motifs and cultural icons. Their manifestations are nearly as kaleidoscopic as the source material they spring from: doe-eyed lolitas in frothy Victoriana, spunky schoolgirls in sailor uniforms saving the world, flame-haired spitfires wielding outsized swords, magical girls whose psychedelic transformation sequences carry the visual fanfare of a butterfly erupting from its chrysalis—the list goes on, often coexisting and overlapping in a disjointed medley that functions in equal parts as a paean to, and a pastiche of, femininity. Sometimes these girls serve as one-dimensional eye-candy within the mise-en-scène. Other times, they are the protagonists and the key players upon whom the plot itself pivots—at once powerful exemplars of gender-identity and Derrida-esque deconstructions of it.

Of course, one might argue that Western media is steeped in similar portrayals of femininity that either defy or mold themselves to patriarchal presuppositions. What, then, lends the figure of the archetypal animanga girl such transnational allure? Some argue that she represents female empowerment in its most multi-layered and triumphant form. She subverts pervasive stereotypes of Japanese women as submissive and sweet, while resonating with female audiences globally by shedding light on uniquely personal facets of 'girlhood' left unexplored by Western media. Others argue the opposite: that she holds such salacious sway largely because she is so fetishized and objectified as to become a ghastly chimera of borderline, if not outright, pedophilia—not to mention a damaging perpetuation of Japan itself as a bizarre wonderland of sexual vagaries.

However, one might just as easily argue that her appeal is rooted neither in gender boundaries, or their subversion. Rather, it is in the shadowy lacuna she occupies in the middle, as a liminal fantasy-figure of both transformation and possibility, whose struggles toward selfhood are at once uniquely Japanese and universal. At home she embodies the attractive nexus of nostalgia and hope: the bittersweet stage of girlhood that must yield inevitably to adult responsibilities of marriage and motherhood. Abroad, she epitomizes the classic stage of youth that is the threshold to something greater, but which in itself can never be recaptured—the ideal metaphor not only for coming-of-age, but for finding within that ephemeral space the freedom to discover oneself in a globalized sphere.

By themselves, of course, anime and manga increasingly occupy a critical space within the larger framework of non-diasporic globalization. Surfing a wave of popularity across different peer-to-peer platforms; fervently discussed and dissected on public and private forums across the Internet; pirated, scanlated, fansubbed and widely shared across networks—the mediums have engendered their own subcultures within a free-flowing landscape unbound by both legal and geographic constraints. According to Japan's Internal Affairs and Communications Ministry, anime outrivals the rest of the nation's TV exports at a shocking 90%. Similarly, manga sales in the US alone have witnessed exponential growth, skyrocketing from $60 million in 2002 to $210 million in 2007 (Suzuki, 2009). The sheer saturation of these mediums across global markets has lent them the term "meta-genre," raising compelling questions about the crux of their appeal (Denison, 2015).

A number of scholars have weighed in on the subject, with many arguing that the je ne sais quoi of animanga lies beyond conceptual occurrences such as synecretism and (pop) cultural osmosis. Rather, it is in the vacuity of the genre itself, not as a quirky emblem of 'Japaneseness' but as its total negation. Koichi Iwabuchi, in his most celebrated monograph Recentering Globalization, refers to this as "cultural odorlessness," or mukokuseki. In Iwabuchi's view, the critical markers of 'Japaneseness'—whether racial, cultural, symbolic or contextual—are absent from animanga, allowing for their easy diffusion throughout the world (2007, p. 24). Similarly, in her work Adult Manga: Culture and Power in Contemporary Japanese Society, sociologist Sharon Kinsella equates the ubiquity of manga to 'air,' owing as much to the diversity of the genre as to its scope of dissemination—one that nearly verges on cultural dilution (2005, p. 4).

Charged within the non-quality of 'odorlessness,' however, are compelling historical undercurrents. Scholars such as Hiroki Azuma argue that the cultural nullity of manga and anime is rooted as much in Japan's humiliating defeat in WWII as it is in its desire to reinvent itself on the global stage. Similarly, Joseph S. Nye equates the easy circulation of animanga with the careful crafting of a frictionless "soft power." Indeed, he speculates that the strategy proved imperative for a nation that had renounced its militaristic ambitions, and whose past was already embroidered with rich narrative threads of cultural eclecticism and fusion (2009). Similarly, in his article The Other Superpower, journalist Douglas McGray remarks that, "At times, it seems almost a strange point of pride, a kind of one-downmanship, to argue just how little Japan there is in modern Japan. Ironically, that may be a key to the spread of Japanese cool" (2009). Of course, the very notion of "soft power" belies the apparent frivolity of animanga's commercial success. After all, Nye avers that the concept of soft power is entrenched in two-thirds statist influence, in particular political ascendancy and the assertion of foreign policy. The underlying purpose is to enhance the nation's scope of influence by lulling foreign audiences with appealing values, whether genuine or simulated, that the nation allegedly embodies.

Naturally, this is no guarantor that the strategy will prove lasting or effective. As Nye notes, "Excellent wines and cheeses do not guarantee attraction to France, nor does the popularity of Pokemon games assure that Japan will get the policy outcomes it wishes" (2009, p. 14). However, there is no denying, either, that the mediums of anime and manga, while perceived as 'odorless,' are nonetheless imbued with a distinct whiff of Japaneseness. This proves apparent in everything from their production to their absorption. Despite transcending national borders, their characters attractively packaged in ambiguously 'Western' skin-tones, hair-colors and attitudes, their realms of storytelling blatantly divorced from superficial signifiers of Japan, they still carry within them undeniably Japanese themes and ideologies. Series such as Blood+ blend trenchant international intrigue with a vampiric appetite for gore, yet tie the value of family to a poignantly Okinawan catchphrase—Nan-kuro-naisa, or It will all work out (2006). Similarly, the technologized labyrinth of Ghost in the Shell boasts a polyphonous, fragmented and multi-ethnic universe that practically embodies the liminal edge of cyberspace itself, yet within which Japan asserts its presence as a shadowy nation state, as well as through characters with patently Japanese monikers such as Makoto Kusunagi, Batou, Saito etc (2002). In his work, Paradoxical Japaneseness: Cultural Representation in 21st Century Japanese Cinema, Andrew Dorman stresses that such narrative elements of Japaneseness are not accidental but deliberate, remarking:

As a method of successfully adapting films for a wider, more diverse audience, cultural concealment softens the impact of Japan's cultural presence in the global marketplace. Yet this does not constitute an erasure of Japaneseness, as indicated by Iwabuchi's concept of cultural 'odorlessness.' In anime's case, Japaneseness is inherent rather than explicit... Rather than disappearing, Japan asserts its presence in ways that are paradoxical, contradictory, and, as anime demonstrates, disorienting. 'Japaneseness' is very much fluid... there can be a distinctly Japanese method of appearing culturally ambiguous with Japanese exports (p. 45).

Similarly, in his book, Consuming Japan: Popular Culture and the Globalizing of 1980s America, Andrew C. McKevitt points out that, "...Cultural odor is relative to the nose of the smeller, what seem[s] denationalized to a prominent anime director could smell a lot like Japan to a young person in California" (p. 182). Indeed, even a cursory examination of Japan-centric scholarship—both among Western academia and otherwise—yields a fascinating oeuvre concentrated entirely on animanga: proof in itself that despite being lauded as hybrid marvels of transnationalism, within these works lingers a manifestly Japanese identity. To alight upon the genre as a stillborn phantom of Japan's ambitions for global leverage, only to then trivialize it because of the chameleon-like mutability of its nature, is missing the point entirely. The more Japan sheathes its cultural specificity within an aestheticized facade of multicultural ephemera, the easier it is to forget that this decontextualization is deliberate, and that it is part of Japan's broader efforts to re-situate itself within a fluctuating globalized sphere—on its own terms.

What better figurehead, then, for a metaphoric yacht of such intangible yet undeniable force than a young girl on the cusp of maturity? Her faces and personalities are kaleidoscopic; yet in her essence she is singular, precisely because she is always amenable to transformation and transmutation, accretion and erasure—much like modern Japan itself. Anime and manga abound with her image: whether as a dreamy Miko resplendent in a white kimono and red hakama, the breeze stirring her hair alongside delicate drifts of cherry blossoms, to a bratty Yakuza princess complete with a chauffeur-driven car and a Chanel handbag, to a shy high-school girl with a pleated sailor fuku and tragic secrets lurking behind her guileless eyes. From warrior to idol singer, magical girl to maid, she has no fixed personae. Instead, she enjoys numberless variations of tropes, numberless ways of veering between cute and cutthroat, dark and light. Her character design is often seamlessly entwined to a target audience: a playful vixen from a bishōjo, or "beautiful girl," series aimed largely at men, a voluptuous sidekick from a seinen (young boys) manga, or a cutesy superheroine hailing from the shōjo (young girls) demographic.

The treatment of the shōjo heroine in animanga is of particular interest, owing as much to the wild popularity of works such as Sailor Moon as to the prevalence of young female leads in renowned films such as Princess Monoke, Kiki's Delivery Service, Blood: The Last Vampire, and The Girl that Leapt Through Time. Embraced by audiences both in Japan and abroad, she appears to be as much a national emblem as a state of being. In her work, Millennial Monsters: Japanese Toys and the Global Imagination, Anne Allison notes that, "...The shojo (as both subject and object) has come to stand as counterweight to the enterprise society: a self indulgent pursuer of fantasy and dreams... shojo have been given a cultural and national value of their own (p. 187)."

What, however, does the term shōjo encompass? At its simplest, the word is used in Japan's publishing industry to refer to a female target-demographic, typically pre-or-post adolescent. However, at its most complex, shōjo has evolved as a genre unto itself, spanning multiple styles, from romance to sci-fi, as well as accruing viewership both young and old. Far from a notch on the proverbial totem pole of social development, the shōjo protagonists of animanga have come to represent an intriguing hybrid space. They are defined as feminine, yet not: the badge of true womanhood naturally bestowed upon wives-and-mothers, with their would-be lofty goals of childbearing and nurturance. The shōjo heroine, however, is unfettered by such constraints. She exemplifies within herself the endearing nativity and brash independence of childhood.

The history of the shōjo's intriguing cultural construct can be traced back to the Meiji period, when the nation's efforts to promote female literacy led to the creation of the Higher School Order in 1899, and the subsequent establishment of all-girls' schools. The era also saw a plethora of text-based and illustrative magazines aimed specifically at young girls—originally to enculture them on government-sanctioned ideals of chastity and domesticity. With the passage of time, however, these girl-oriented communities increasingly became a space to explore femininity through a polychromatic lens, as opposed to a narrowly monochrome beam of patriarchy. Freed from the masculine aegis, this was one arena where young women could unlock otherwise stymied voices and discover their true selves.

Novelists such as Yoshiya Nobuko gained particular renown for heroines who wore the fabric of empowerment so daringly yet delicately, celebrating rather than denying their femininity. The theme of Nobuko's works seldom revolved around marriage; rather, they cast a soft focus on the hidden worlds of the feminine, from navigating the complex waters of sexuality to bittersweet lessons in friendship and heartbreak. Indeed, a number of Nobuko's stories, such as Hana Monogatari (Flower Tales), have wielded considerable influence on contemporary shōjo classics, from Chiho Saito's Revolutionary Girl Utena to Ai Yazawa's Nana, both of which chronicle, not the protagonists' relationships with men, but the curious and complicated lives of the women at the heart of each narrative (Abbott, 2015; Robertson, 1998).

As expected, the shōjo genre's blithe subversion of gender standards did not sit well with Japanese society. In her work, The Human Tradition in Modern Japan, Anne Walthall remarks that, "The treatment of ... the shōjo period by the popular media in turn-of-the-century Japan reveals a Janus-faced object and subject of scrutiny... [It] began to grow into a life-cycle phase, unregulated by convention, as more and more young women found employment in the service sector of the new urban industrializing economy" (2004, p. 158-159). By the time of the Taishô democracy, the ranks of shōjo were graced by another, more contradictory feminine aesthetic— the flirty, flapper-esque "modern girl," or moga. Outgoing and brazenly occidentalized, the moga was cast by popular media as the antithesis of ryōsai kenbo (good wife and wise mother). She represented, in many ways, Japan's uneasy, almost bipolar relationship with Western modernity. With her sleekly bobbed hair and the swish of her short skirt, she trod carelessly over the sacred orthodoxies of gender and tradition. In spurning the conventions of marriage and motherhood, she was deemed aimless, vapid, and, in her own way, deviant. Indeed, it was not long before the very notion of shōjo, originally a benign emergent space within a modern but quintessentially Japanese framework, became perceived as its Ruben-Vase opposite: a symbol of Western decadence and disorder. The shōjo heroine, toppled from her pedestal of pure and timorous girlhood, came to occupy a freakish position outside the gender binary. In her work, Transgendering Shōjo Shōsetsu: Girls' Inter-text/Sex-uality, Tomoko Aoyama likens the shōjo girl to almost a third sex, describing her as "free and arrogant, unlike meek and dutiful musume [daughter] or pure and innocent otome [maiden]" (2005, p. 49).

Both daughter and maiden are, of course, patriarchal determinants. By providing a rebellious counter-note to these traditional roles of sweetness and submissiveness, the shōjo heroine distinguishes herself on yet another level—she is so profoundly Othered as to become an abstraction. This makes her nearly the ideal mascot of any genre in animanga: action, horror, comedy, romance. It is easy to either deify or eroticize an abstraction; like a blank slate, she can be inscribed with whatever values, or lack of them, that her creators (or the nation itself) wish to promulgate. Similarly, audiences can project on to her dreams and desires, whether empowering or exploitative, depending on their lens of scrutiny.

This duality of interpretation has been observed frequently, with the shōjo heroine being lauded simultaneously as a feminist icon, and as a lurid object of fetishization. On the one hand, many have argued that, far from being powerful assertions of the female body's agency, these girls are merely trapped within misogynist narratives. Even in instances when they appear to wield force against their foes, the angle and framing render them objects of male desire, rather than subjects with the freedom to pursue their own (Brazal & Abraham, 2014). Series such as Cutey Honey and Kill La Kill, for example, feature fierce warrior girls battling against insurmountable odds, yet are peppered with cheeky fanservice; diegetically, the girls may be the 'stars' of the show, but in terms of textual construction, they serve as the prurient centerpiece of a visual buffet. On the other hand, it has been argued that, far from depersonalized chess pieces within the plot, such characters are the embodiment of the modern girl's dreams, with the freedom to be both strong and self-indulgent, both desirous and desirable. If they flaunt skin or flout the maxims of modesty, it is because their interpretation of empowerment is a playfully Sadean paradigm, with desire as an act of transcendence.

Whether one interpretation deserves merit over the other is beside the point. The fact remains that animanga's treatment of the shōjo heroine is too self-reflexive to pigeonhole as sexist or feminist, largely because her portrayals play intensely with narrative traditions of reality and fantasy, strength and subjugation. In his forward of Saito Tamaki's book, Beautiful Fighting Girl, J. Keith Vincent notes that people often assume that the animanga heroine is " ...in some sense a reflection of the status of girls and women in Japan... What these analyses often miss, however, is that [she] is also a fictional creature in her own right, and one capable of fulfilling functions other than straightforward representation" (p. 4). One might argue, of course, that the same can be said of any character in popular culture. Good fiction, after all, necessitates a degree of abstraction; characters must be hyper-specific and nuanced enough to seem human, yet deindividualized enough as a walking vacant space so that audiences can slough their skins on and off, say the things they are saying, do the things they are doing. When done correctly, these characters resonate across different social and cultural spectrum, while remaining firmly rooted in their own particular narratives, enabling the audience to achieve a twofold sense of safety and discovery. When done wrong, these characters become bland placeholders who dissolve as little more than white-noise within the narrative itself.

Yet the shōjo heroine, despite exemplifying fluid, nearly ephemeral identity, holds a multicultural allure seldom seen in Western works—one that allows her to straddle different cultures and continents while remaining quintessentially Japanese. In that sense, she almost personifies the essence of Japan's 'soft-power:' disarmingly sweet yet imbrued with all the fluid symbolism of the nation's past, and all the hopeful reinvention of its future. Certainly, Japan's national identity has often seemed a paradoxical blend of East and West, technology and mythology, tradition and innovation, apocalypse and rebirth. The shōjo heroine reflects this cultural propensity by amalgamating within herself these disparate elements in order to create a fresh and unexpected identity of her own. In his work, Japanese Schoolgirl Confidential: How Teenage Girls Made a Nation Cool, Brian Ashcraft remarks that she represents:

...both gruff samurai, strong and powerful, and demure geisha, beautiful and coquettish. Decked out in her Western-influenced uniform, she brings these elements together into a state of great flexibility—the ability to be strong or passive, Japanese or Western, adult or child, masculine or feminine. At home and abroad, she is a metaphor for Japan itself (p. 3).

However, one might argue that, beyond a metaphor for Japan, the archetype of the shōjo heroine proves effective as both a cultural exemplar and an international ambassador because she gives center stage to the realms of fantasy and freedom. This goes considerably beyond puerile leaps of fancy or shallow substitute worlds; she is neither a proxy nor an escape hatch, and for all her trappings of feminism, her narratives are often noticeably depoliticized (although there are exceptions).

Yet within that conspicuous absence of political semiotics, she is hailed as an icon of free-flight on a multiplicity of levels. Part of it has to do precisely with her femininity; otherwise, it could be argued that a young boy would function just as well as a diegetic symbol. Essayist Carmen Maria Machado remarks that being a woman, for better or worse, is intrinsically tied to the uncanny. "Your humanity is liminal; your body is forfeit; your mind is doubted as a matter of course" (Kuhn, 2017, p. 1). This unfixed and mutable image allows for a platform of reinvention and dissolution wherein anything goes, and where dreams or nightmares can be made or unmade.

The shōjo heroine takes full advantage of this transformative capacity. Her different personae allow her to bring something meaningful to extant social reality, by inviting audiences to delve into multifaceted territories and unfamiliar modes of being. Through her, mundane reality acquires a sheen of novelty and mystery; once-unshakeable truths are challenged as the porous constructs they are. The human condition itself is thrown into riveting relief against a larger backdrop, both global and cosmic. Her diverse manifestations offer, as Roland Kelts states in his book Japanamerica, an "increasingly content hungry world with something Hollywood, for all its inventiveness, has not yet found a way to approximate: the chance to deeply, relentlessly and endlessly immerse yourself in a world driven by prodigious imagination" (2006).

The shōjo heroine's cutesy facade does not hinder this approach, but instead enhances the experience for audiences, largely because her character becomes a nucleus of empathy. The formula is successfully employed in several renowned shōjo-genre works. The heroines in series such as Sailor Moon, Princess Tutu and Revolutionary Girl Utena, for instance, approach with insightfulness and sensitivity the agonies of growing up, using their female leads as loci of identification. Equal parts naive and resilient, these heroines exude an endless capacity for hope; although superficially childlike, their warmth becomes a source of strength for other characters, and by proxy the audiences. At the same time, each series employs magic as both a narrative vehicle on the journey toward selfhood, and as a leitmotif of covert psychological meanings. In her work, Magic as Metaphor in Anime, Dani Cavallaro notes that anime employs fantasy tropes, magic and the supernatural as a stylistic vehicle of communication, revealing,

... an increasing tendency to articulate subtly nuanced psychological dramas, pilgrimages of self-discovery and, fundamentally, mature speculations about the nature of humanness and the meaning of living as humans... magic ... by recourse to a paradox, [becomes] a form of obscure illumination: the revelation, by cryptic means, of powerful but often unheeded forces swirling at the core of existence (2010, p. 1-5).

Of course, in Japanese tradition, magic and the human condition have never existed as binary opposites, but as facets of a single quantum spectrum. The fact can be evinced in the nation's culture, both contemporary and historic, within which both Shinto animism and Buddhist values dance hand-in-hand, absorbing into themselves the more recent rhythms of Western occupation, the better to compose astonishing fusions of both indigenous fantasy and fluctuating global trends. The animanga heroine, by virtue of her 'unformed' and 'incomplete' shōjo status, neatly functions as a meta-triage of these forces. However, her true talent is for fusing her self and the audience together through an honest exploration of human experience at its simplest—and its most vulnerable—as well as in her ability to embrace the deficiencies, cracks, and inconsistencies as part of a reassembled whole (Chee & Lim, 2015).

Taken in that sense, one could almost describe her as a microcosm in feminine wrapping. Through her, audiences worldwide witness a smooth synthesis of overarching global vicissitudes and personal instabilities. Sometimes this is achieved lightheartedly, almost hilariously—such as in Cardcaptor Sakura or Kill La Kill, both of which employ a visual extravaganza of mess and mayhem to tartly parodize the everyday pathos of coming-of-age. Other times, her character occupies an ontological penumbra that spans both individual griefs and grave social issues, such as in Madoka Magica or Hell Girl, both of which highlight the particular dangers of transitioning from girlhood to womanhood in a modern era.

Considering the shōjo heroine's history, there is a certain delightful irony to this fact. Originally, as mentioned, the very premise of shōjo arose out of rigidly parochial system in Meiji-era Japan. Yet, within the very space meant to subdue her, she has paradoxically been transformed into an icon of magic and mystery, transgression and self-discovery. At once a pop-cultural emblem of Japan and an international superstar, her true appeal, however, lies in the shadowy lacuna she occupies in the middle—as a liminal figure of possibility, whose struggles echo the more universal themes of reinvention and imagination. At home she is the sprightly figure of a girlhood lost, an epoch of innocence that seems at once eternal yet eyeblink-brief. Abroad, she is imbued with the fleeting transience that practically epitomizes the traditional Japanese aesthetic: a stage of youth that is the threshold to something greater, but which in itself can never be recaptured—the ideal metaphor not only for coming-of-age, but for finding within that amorphous space the freedom to dream, and to grow both roots and wings in a volatile globalized backdrop.

References

Abbott, L. (2015). Shojo: The Power of Girlhood in 20th Century Japan. Honors Theses - Passed with Distinction, Washington State University. Retrieved September 14, 2017, from http://hdl.handle.net/2376/5710

Aoyama, T. (2005) ‘Transgendering Shôjo Shôsetsu: Girls’ Inter-text/sex-uality’, in McLelland, M. and Dasgupta, R. (eds.). Genders, Transgenders and Sexuality in Japan. London: Routledge.

Allison, A. (2006). Millennial monsters: Japanese toys and the global imagination. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Ashcraft, B., & Ueda, S. (2014). Japanese schoolgirl confidential: how teenage girls made a nation cool. Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing.

Azuma, H. (2009). Otaku: Japan's database animals. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press

Brazal, A. M., & Abraham, K. (2014). Feminist cyberethics in Asia: religious discourses on human connectivity. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Cavallaro, D. (2010). Magic as metaphor in anime: a critical study. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co.

Chee, L., & Lim, E. (2015). Asian cinema and the use of space: interdisciplinary perspectives. New York: Routledge.

Denison, R. (2015). Anime a critical introduction. London: Bloomsbury Academic, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing, Inc.

Dorman, A. (2016). Paradoxical Japaneseness: cultural representation in 21st century Japanese cinema. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Fujisaku, J. (Director and Producer). (2006). Blood+ [Television Series]. Tokyo, Japan: Production IG.

Iwabuchi, K. (2007). Recentering globalization: popular culture and Japanese transnationalism. Durham: Duke University Press.

Kamiyama, K. (Director and Writer). (2002). Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex. [Television Series]. Tokyo, Japan: Production IG.

Kelts, R. (2006). Japanamerica: how Japanese pop culture has invaded the U.S. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kinsella, S. (2005). Adult manga: culture and power in contemporary Japanese society. London: Routledge Curzon.

Kuhn, L. (2017, September 27). 'Being a Woman is Inherently Uncanny': An Interview With Carmen Maria Machado. Retrieved October 13, 2017, from https://hazlitt.net/feature/being-woman-inherently-uncanny-interview-carmen-maria-machado

McGray, D. (2009, November 11). Japan’s Gross National Cool. Retrieved September 14, 2017, from http://foreignpolicy.com/2009/11/11/japans-gross-national-cool/

McKevitt, A. C. (2017). Consuming Japan: popular culture and the globalizing of 1980s America. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press.

Otsuka, E and Nobuaki, O. (2005) "Japanimation" Wa Naze Yabureruka [Why Japanimation should be Defeated]. Tokyo: Kadokawa Shoten.

Richie, D. (2007). A Tractate on Japanese Aesthetics. Berkeley, CA: Stone Bridge Press.

Robertson, J. E. (1998). Takarazuka sexual politics and popular culture in modern Japan. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Saitō, T., Vincent, K., Lawson, D., & Azuma, H. (2011). Beautiful fighting girl. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Suzuki, Y. (2009) "ROK promotes TV dramas." Daily Yomiuri. June 20: 4.

Walthall, A. (2004). The human tradition in modern Japan. Lanham, MD: SR Books.

0 notes

Text

Phytotherapy: How to use Plants or Parts of Plants?

Phytotherapy: How to use Plants or Parts of Plants?

Phytotherapy: How to use Plants or Parts of Plants?

Although there are currently many plants extracts in the form of food supplements that have the triple advantage of being easy to take, of not requiring any preparation effort, and often of offering a controlled content in Active ingredients, it can be a lot of fun to prepare your own herbal remedies (Phytotherapy). It is also in the interest of being able to use any of plants, provided that you have it at your fingertips. Not all plants are found in the form of food supplements. Take the simple example of the fragrant Woodruff: This small white flower that grows in the spring in the undergrowth and which is deliciously scented by drying... It is difficult to get it in capsules or in a tea bag. On the other hand, you only need a walk in the forest and a single harvest to enjoy it all year round!

Harvesting plants or parts of plants

What are you going to reap? Choose plants that you know well and that you are not likely to confuse. Some plants are poisonous. Nature is not always merciful with the picker... Just a few leaves of Laurel-Rose, a little hemlock, datura or digital to do you a lot of harm! The identification of plants is therefore paramount. The ideal, to learn, is to walk with a person keen in botany. There are also many structures, often associative, that offer hikes or even internships to discover the flora and its benefits.

When you have filled your basket with leaves and flowers, what are you going to do with your harvest? First of all, check well, one last time, that you have correctly identified the plants. If necessary, look on a guide to the Flora or, in this book, and carefully compare the descriptions; But, again, there is nothing like doing his pickings accompanied by a connoisseur, at least the first few times.

Depending on the time of flowering, maturity and the parts of plants concerned, harvest times vary. In spring and summer, it is mainly planted, whose active ingredients are concentrated in the leaves, and especially the flowers that are interesting.

Choose a dry and sunny day avoiding the stormy atmosphere. Make your harvest preferably in the morning, when the dew is completely evaporated, or failing in the evening, but before the moisture has fallen. Plants or parts of plants must not be wet, otherwise, they may ferment and rot, and lose all their qualities.

The Necessary Equipment

Sharp scissors and knives are imperative for cutting the rods sharply. To prevent the plants from spoiling, be careful not to crush them: a basket is the best container to deposit your pick. It is strongly advisable not to mix the different parts of plants during the harvest. You can take several baskets, otherwise, you only collect one plant during your walk. And most importantly, do not let your crop piled up in the basket when you get home: When you return, take care of your plants.

Where to pick?

The more the place of your picking will be from the urban areas and the crops, the better your harvest will be. Nothing beats a place a little wild. Pay close attention to the plant environment: if there are a few fields in the vicinity that are regularly planted with fertilizers and pesticides, there is no need to linger. Do not pick contaminated plants. Avoid also dust-covered plants that grow along roadsides and roads. We never wash the parts of plants that we collect, so they must be clean when picking.

The Basic Rules

When picking up or cutting plants, dispose of small wastes (other plants, debris, etc.) before putting them in your basket. This is much easier to do at harvest time than later on. be strict on quality, because the plant must be perfect: wilts, discolorations, leaves nibbled and stains are all faults to be taken into account. Especially since defects are often contagious and you may "condemn" your entire crop.

Dry and Keep

To dry the roots, flowers, bulbs, berries, and fruits, hang them or spread them without overweight on racks or crates, usually in the shade in an airy place (e.g. in the attic). If the roots are fleshy, it is better to cut them into slices. The stems and leaves can be dried in the sun. Once your plants are dried, distribute them, without mixing them, in paper bags, envelopes of letters or cardboard boxes. Avoid plastic and metal... and shoe boxes, even new ones (to prevent the plants from absorbing bad odors).

If you Grow your Own Plants

Aromatic and medicinal plants (parts of plants) are generally quite undemanding, often those that grow wild in wastelands. They won't make any trouble to invade your garden! Preferably put them in a place sheltered from the wind. If you don't want to ask questions, sow and replant in sterile soil. If you are a perfectionist, you should know that garlic, rosemary, alchemilla, marjoram, mint, hyssop, sage, oregano, juniper, laurel, hazel, lime, campaniles, poppy, Blueberry, and bus prefer a slightly alkaline soil: spread once or twice a year from Ashes of wood and limestone. In addition, Citronella, borage, knapweed, chamomile, thyme, fennel, lavender, and bulbous or tuber plants prefer more sandy land. Therefore, separate these two broad categories.

Planting

They sow as soon as March under a greenhouse or in the House near a window exposed to the south and, after the frosts, in the shelter, until July. Seedlings are usually carried out on potting soil, spacing the seeds, and then lightly filling them with the dish of the hand. Most aromatic plants germinate at 15-21 °c within a few days. You will transplant 4 to 6 weeks later. If you have late sowing, you will leave it in place by spacing the seedlings. Follow the instructions on the pouch to see how much water to sprinkle or what is the best germination temperature. In summer (June, July), you can make a seedling directly in place (without subculturing).

The Division

Every 2 or 3 years, divide the woody plants (thyme, rosemary, Lavender...) or bushy (sage, Queen of the Meadows, chamomile, St. John's Wort, Mint...): It is enough to clear the Earth on one side, to separate the roots by hand, to replant and to water.

Cuttings

It's pretty hard to succeed, but it's worth a try when you have no seeds or roots: cut it in a neat, slanted way, about ten centimeters above the hard part of the stem. Remove the leaves on one-third of the stem. Plunge the cutting into the water, wait for it to produce roots, and then replant it in a pot with potting soil. Before fall, replant in the middle of the earth.

Potted culture

Most medicinal plants (basil, lavender, rosemary, serpolet, hyssop, mint, parsley, queen-of-Meadows, St. John's Wort...) can be grown in pots. The larger and deeper the container, the more the plants will spread. If you grow your plants inside, make sure, on the one hand, that the room temperature does not exceed 18 to 19 ° and, on the other hand, that the plant has natural light at least 8 hours per day. Herbal remedies generally do not appreciate draughts, think about it when you decide on the place you reserve them in the house.

Herbal Teas

What if I told you that nothing would ever replace a good herbal tea? It's true, it's a little time, you have to heat water, wait until it boils or it infuses, but frankly, it's worth it! Because while you're "caring", you drink! Good water loaded with active ingredients. Moreover, even if, a few years ago, the herbal teas were relegated in the "Grandma" ray with slight contempt, they are again in the stern.

You can choose a single plant or mix them, depending on the tastes or effects you are looking for. Apart from some recipes coming from famous herbalists, I took the party, in this Bible, to propose simple herbal teas according to the indications: Linden Flowers against the flu, Hawthorn in case of palpitations, dandelion roots for the liver ... But each time, many plants can be useful and it is quite possible to mix them.

To do this, you have to choose plants or parts of plants that can be prepared together: if you put roots that must be boiled to extract the active ingredients with flowers that only support the simmering water, this will not be appropriate Not. For example, queen-of-meadow flowers should not be boiled with burdock root: The Queen of the Meadows would lose many of its active ingredients during the boil.

In case of rheumatism, for example, you can mix the leaves of blackcurrants and flowers of queen-of-meadows equally and drink 3 cups of herbal tea a day (1 tablespoon of the mixture infused 10 minutes in a cup of boiling water). If you have skin problems, boil 40 g of a burdock root mixture and wild thought for 10 minutes and then infuse 5 minutes before filtering. Drink the mixture in the daytime. If you are preparing enough herbal tea for 1 or 2 days, keep it cool and, depending on your taste, make it more or less warm when you drink it.

What you Need for your Preparations

Carefully choose your equipment by preferring enameled pots and wooden spoons. The fewer plants are in contact with metal or plastic, the better.

Avoid aluminum utensils and containers that can be toxic and that the plants absorb. To preserve your herbal teas, prefer cardboard boxes or glass stoppers that you store in the shelter of light.

Depending on the plants and especially the parts of plants used to make their herbal tea, the method of preparation is different. Infusion is well suited to flowers and leaves in general, the most fragile parts of plants. The decoction is mainly used for roots, stems, and barks.

The water used must be as pure as possible and weakly mineralized, such as spring water or, better still, osmosis water. Avoid tap water. We often have the habit of drinking herbal teas in the evenings, but they can accompany the days. Why not take the habit of drinking 1 liter of herbal tea between meals, for example? By varying the mixes according to your tastes and the effects you expect.

The Brew

It consists of pouring boiling water on plants at the precise moment when the water boils. You then put the plants in the water, stir lightly and cover the pan. Then allow the necessary time (from a few minutes to 1 hour depending on the plants) to brew. You can beat with a tea whip (bamboo) or a wooden spoon to speed up the diffusion of active ingredients. When the brewing time is enough, filter and drink. You can eventually sweeten with honey, but the ideal is still the "pure" herbal tea unless you have a sore throat. In this case, honey will be ideal. Prefer bulk plants rather than tea bags that often contain "crumbs" or even plant dust.

The Decoction