#The California Geological Survey

Text

Arroyo Toad (Anaxyrus californicus), tiny baby toadlet, family Bufonidae, southern California, USA

ENDANGERED.

photograph: U.S. Geological Survey/Chris Brownn

145 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some of the world’s largest investment banks, pension funds and insurers, including Manulife Financial Corp.’s John Hancock unit, TIAA and UBS, have been depleting California’s groundwater to grow high-value nuts, leaving less drinking water for the surrounding communities, according to a Bloomberg Green investigation. Wall Street has come to Woodville, wringing it dry. Since 2010, six major investors have quadrupled their farmland under management in California, to almost 120,000 acres in all, equivalent to a third of all the cropland in Connecticut.

[...]

This rush for water is an outgrowth of a decades-long bet on farmland by investors who see food cultivation as an asset class virtually assured of appreciating in a warming, more populous world. Globally, large investors and agribusinesses have snapped up about 163 million acres of farmland in more than 100 countries in the past 20 years. The land grab has given rise to a grab of an even scarcer global commodity: water. In a bid to ensure thriving investment portfolios, some of the world’s largest financial entities have amassed control over lakes, rivers and underground aquifers in places from California to Africa, Australia to South America, giving them outsize roles in managing an endangered resource that’s the basis of life on Earth. The trend has contributed to shifting hydrological patterns that stand to permanently disrupt communities’ access to fresh water. Local populations are paying the price in drained wells, high water bills and contaminated water supplies.

[...]

In the past decade, parts of the San Joaquin Valley have dropped as much as a foot per year, according to the US Geological Survey. Subsidence, as the sinking is called, has damaged bridges, canals and other infrastructure that will cost billions of dollars to fix, the state says. The aquifers themselves are irreparable. Many groundwater basins, when drained, never recover their former storage capacity, hydrologists have found. “Groundwater in California has been treated as an extractive resource—you pump and hope for the best,” says Graham Fogg, an emeritus professor of hydrology at the University of California at Davis. “Capitalism is driving this. Investors don’t care, because in 10 years they can make all the money they want and leave.”

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

Remembering March 11, 2011

On March 11, 2011, a magnitude (Mw) 9.1 earthquake struck off the northeast coast of Honshu on the Japan Trench. A tsunami that was generated by the earthquake arrived at the coast within 30 minutes, overtopping seawalls and disabling three nuclear reactors within days. The 2011 Tohoku Earthquake and Tsunami event, often referred to as the Great East Japan earthquake and tsunami, resulted in over 18,000 dead, including several thousand victims who were never recovered.

The deadly earthquake was the largest magnitude ever recorded in Japan and the third-largest in the world since 1900.

How It Happened

The 2011 event resulted from thrust faulting on the subduction zone plate boundary between the Pacific and North America plates, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

This region has a high rate of seismic activity, with the potential to generate tsunamis. Past earthquakes that generated tsunamis in the region have included the deadly events of 1611, 1896, and 1933.

The March 11, 2011 earthquake generated a tsunami with a maximum wave height of almost 40 meters (130 feet) in the Iwate Prefecture. Researchers also determined that a 2,000-kilometer (1,242-mile) stretch of Japan’s Pacific coast was impacted by the tsunami.

Following the earthquake, a tsunami disabled the power supply and cooling of three Fukushima Daiichi reactors, causing a significant nuclear accident. All three nuclear cores largely melted in the first three days.

As of December 2020, the Japan National Police Agency reported 15,899 deaths, 2,527 missing and presumed deaths, and 6,157 injuries for the Great East Japan event.

High Costs

In Japan, the event resulted in the total destruction of more than 123,000 houses and damage to almost a million more. Ninety-eight percent of the damage was attributed to the tsunami. The costs resulting from the earthquake and tsunami in Japan alone were estimated at $220 billion USD. The damage makes the 2011 Great East Japan earthquake and tsunami the most expensive natural disaster in history.

Although the majority of the tsunami’s impact was in Japan, the event was truly global. The tsunami was observed at coastal sea level gauges in over 25 Pacific Rim countries, in Antarctica, and on the west coast of the Atlantic Ocean in Brazil.

The tsunami caused $31 million USD damage in Hawaii and $100 million USD in damages and recovery to marine facilities in California. Additionally, damage was reported in French Polynesia, Galapagos Islands, Peru, and Chile.

Fortunately, the loss of life outside of Japan was minimal (one death in Indonesia and one death in California) due to the Pacific Tsunami Warning System and its connections to national-level warning and evacuation systems.

Read more

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

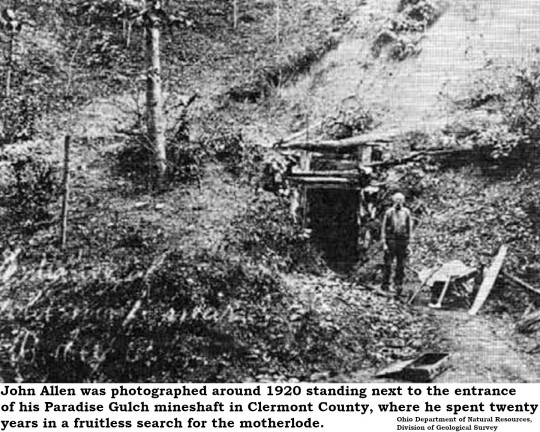

Remembering The Long-Forgotten Clermont County Gold Rush Of 1868

Byron Williams, who published the exhaustive 1913 history of Clermont and Brown counties in Ohio, spares not a single word in his two-volume epic for the gold rush of 1868. Perhaps this is understandable.

Compared to the renowned California Gold Rush of 1849, the Clermont County gold rush of 1868 was hardly noticeable outside a handful of incurable optimists. Oh, there was gold in the creeks east of Cincinnati, it is true. There’s still gold there and it is easily found. The problem is, it takes a lot more time, money and effort to get that gold out than it is commercially worth – even at the lofty prices gold has claimed since it was deregulated in 1975. The economic futility of Ohio gold was summarized as early as 1873 in the report of Ohio State Geologist Edward Orton:

“From what has already been said, it will be seen that Clermont County has no monopoly of the gold-bearing formation of Ohio. This formation should be named the ‘Drift gold field,’ rather than the ‘Clermont County gold field.’ All of the counties of southwestern Ohio certainly share in its treasures, and without doubt one locality is as good as another, where gravels are found that have been washed from the bowlder clay. The best results thus far known to have been obtained in gold-mining in Ohio are reported for Warren county, where in one day gold to the value of six dollars was obtained – by an outlay of ten dollars; a half-dozen days’ work being also thrown in.”

Nevertheless, there are some folks for whom the gold fever never subsides, and Clermont County has been subjected to hard-working miners and unscrupulous fraudsters in approximately equal measures ever since. According to the Spring 1985 newsletter of the Ohio Geological Survey:

“Gold was first discovered in Clermont County on the farm of Robert Wood, near Elk Lick, on the banks of the East Fork of the Little Miami River. This site is now located on the north shore of William H. Harsha Lake at East Fork State Park.”

It is almost certain that any discovery of gold will attract equal numbers of hard-working miners and shady flim-flam men. Several stock companies were set up to finance gold-digging operations in Clermont County, but few paid dividends. The newspapers were full of breathless proclamations of easy riches. “Professor” J.W. Glass announced in the Ohio Statesman [21 September 1868]:

“I believe that were we supplied with an abundance of water for hydraulic purposes, our hills would pay equally well as those of California.”

Glass estimated that hand-panning would yield no more than fifty to seventy-five cents worth of gold in a day, while hydraulic mining could generate anywhere from twelve to fifteen dollars a day. A correspondent signing himself M. Jamieson informed the Cincinnati Gazette [31 August 1868]:

“Old California miners have prospected over a good portion of this field, and report gold in almost any ravine where they tried their luck. Those miners seem sanguine, and say they found no better diggings in California.”

Alas, such wishful appraisals never, shall we say, “panned out.” The Cincinnati Post [22 Januray 1897] echoed State Geologist Orton while taking an honest look at the situation:

“Every year or so some newspaper correspondent in Clermont County, Ohio, or some contiguous county sends a report of the discovery of gold and of mining enterprises for its recovery. These reports of gold in these counties are true. It has not been found to be minable, because it costs about $5 – in money and labor – to get out $1 in gold.”

That judgement didn’t prevent the Post from printing, just eight years later, a small feature on Clermont miner John Allen, who had dug a 200-foot tunnel into a hillside along Cabin Run Creek in an area known as Bear Hollow. Allen called his mine Paradise Gulch and worked it without ever striking the mother lode into the 1920s. His mine shaft is now collapsed.

Allen failed to find the source of the gold flakes extracted from nearby creeks because he misunderstood the local geology. Unlike California, where seams of gold up in the hills erode into flakes of placer gold in the streams, Ohio has only placer gold. The mother lode for Ohio’s gold is somewhere up in Canada and all the gold found here was dragged south by the glaciers that once blanketed our state.

Gold fever revived in the 1930s when the regulated value of the precious metal was boosted to $35 an ounce and so many men were out of work due to the Great Depression. A farmer named Robert Titus found a few gold flakes in a creek that ran through his farm and set up a company to exploit the find. Titus built a gasoline powered sluice that could sift a cubic yard of gravel and sand in less than an hour. According to the Ohio Geological Survey:

“Considerable excitement was created by this venture and Titus was reportedly offered financial backing and outright purchase of his 40-acre farm for $1,500 per acre. No commercial quantities of gold were ever produced from this deposit and most of the metal recovered was sold for souvenirs.”

Today, Clermont County prospectors are almost exclusively hobbyists. The Cincinnati Mineral Society has led occasional field trips to a tributary of Stonelick Creek since the 1960s, as has the Cincinnati Museum of Natural History and Science.

Still, the lure of gold fires the imagination. Michael Hansen of the Ohio Geological Survey recalled the heady days of gold speculation in the 1980s:

“In early 1980, when gold prices skyrocketed to more than $800 per ounce, the survey received up to 600 letters each week after newspaper articles across the state identified the Survey as the organization responsible for such matters in Ohio.”

7 notes

·

View notes

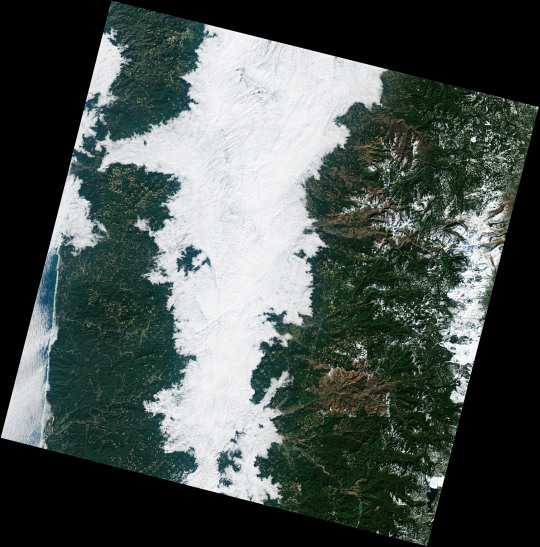

Photo

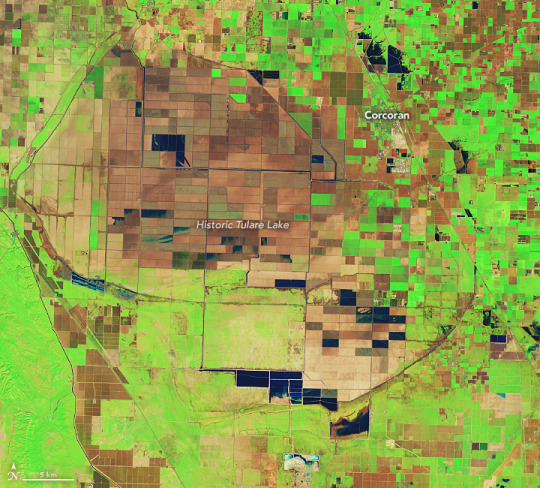

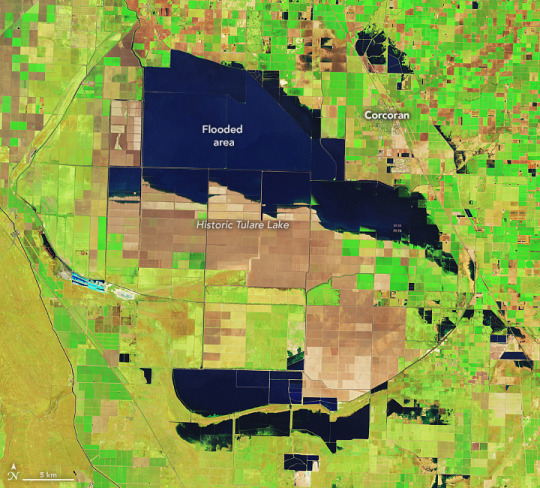

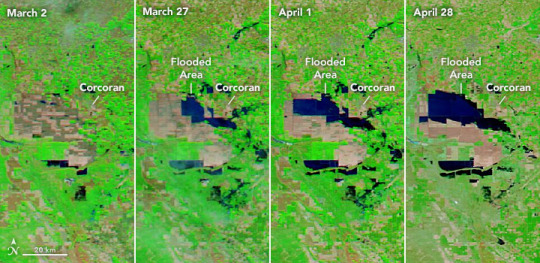

Tulare Lake Grows The San Joaquin Valley sits like a bowl at the base of the southern Sierra. Close to the middle of that bowl is the historic lakebed of Tulare Lake, which was once the largest freshwater lake west of the Mississippi River. Since the 1920s, the rivers that fed the lake have been dammed and diverted for agriculture and other uses. The lakebed has since been covered with farms that produce a variety of crops and livestock. But after two major storms hit southern California in March 2023, water once again returned to Tulare. The image above (centre), acquired by the Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8, shows flooded farm fields in the lakebed on April 30, 2023. The image on the top—acquired by the OLI-2 on Landsat 9—shows the same area on February 1, before significant flooding started. These images are false color, which makes the water (dark blue) stand out from its surroundings. Vegetation is green and bare ground is brown. The lower images show the progression of flooding in the Tulare Lake basin. They were acquired by the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Aqua satellite between March 2 and April 28, 2023. Flooding in the lakebed is likely to continue into 2024, which will affect residents and farmers in the area, as well as some of the most productive cropland in the Central Valley. The lakebed contains farms that produced cotton, tomatoes, dairy, safflower, pistachios, wheat, and almonds. The town of Corcoran, on the edge of Tulare’s historic extent, is at risk of flooding from the rising waters. A 14.5-mile L-shaped levee stands between the farm town and the flooding. The community recently began a project to raise the height of the levee by 4 feet, to prevent the levee from being overtopped. Meltwater from the snowpack on the southern Sierra—which was four times the average in April—is a major source of water for the Tulare Lake basin. Sierra meltwater streams into Kern River, which flows from the Sequoia National Forest in the southern Sierra, past Bakersfield, and ultimately empties into Tulare Lake. Along the way, the river also contributes to Lake Isabella, a dammed reservoir in Sequoia National Forest that has been filling with water this year. High levels of water along the Kern have led managers to discharge water from the river into ponds just west of Bakersfield. Flooding these recharge ponds allows water to seep into aquifers for long-term storage. The graphic below shows these flooded ponds on April 30, 2023, compared to February 1. The images were acquired by the OLI on Landsat 8 and the OLI-2 on Landsat 9, respectively. “All the dark blue water you see is being managed in recharge ponds,” said Kern River watermaster Mark Mulkay, after seeing the images. In anticipation of more meltwater coming down from the Sierras, local and federal water managers are releasing water into ponds like these not only to store water for future use but also to prevent uncontrolled flooding along the river and the Isabella Reservoir to the east. “This early water recharge will keep flood water from the Kern out of Tulare Lake to help minimize the flood damages in that area,” Mulkay added. Snowpack in the Sierras is not finished delivering challenges to the San Joaquin Valley. Spring snowmelt has just begun, and according to the May 1 snow survey by the California Department of Water Resources, snowpack on the entire range is still twice the normal level. NASA Earth Observatory images by Lauren Dauphin, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey and MODIS data from NASA EOSDIS LANCE and GIBS/Worldview. Story by Emily Cassidy.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fog Down in the Valley

"The Willamette Valley in Oregon is rich with farms and orchards, home to 70 percent of the state’s population, and dotted with more than 500 wineries. But all of that can disappear under a blanket of white when the valley fills in with fog, as it has several times in recent weeks.

Fog is common in the region in the autumn and winter, as moist Pacific air moves inland, cools, and sinks into the vast valley between the Cascade Mountains and the Oregon Coast Range. As that air gives up its heat to the upper atmosphere, the layer near the surface becomes saturated and essentially forms clouds at ground level.

Such fog has been locked in the Willamette Valley for several long stretches in January and February 2022 due to temperature inversions, where warm air high in the atmosphere moved in over the cooler, denser air in the lowlands. Normally, temperatures are warmer at the land surface, cooling higher up in the sky. This allows for most of the rising air and pollutants to continue to disperse out into the atmosphere. But an inversion acts like an atmospheric “lid” that can trap moisture and air pollution in a valley for days.

On February 10, 2022, the Operational Land Imager-2 (OLI-2) on Landsat 9 acquired these natural- and false-color views of thick fog in the Willamette Valley. The false-color image was composed from shortwave infrared, near-infrared, and red light (OLI-2 bands 6-5-4). Scientists turn to these wavelengths to distinguish clouds (white and pink) from snow and ice (cyan).

Oregon has already seen at least three extended periods of valley fog in 2022, as observed by the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Terra satellite from February 8-12, January 22-29, and January 14-17.

Fog is essentially a low-lying cloud composed of tiny water droplets suspended in the air. As nights lengthen with the season, the atmosphere has more time to cool down and approach the dew point—the temperature at which the air becomes saturated and water vapor condenses into fog. Since cold, moist air is denser than warm air, it sinks and drains into valleys, meaning fog develops there first. Many valleys like the Willamette also have rivers and streams that amplify the fog with a ready supply of moisture.

Fog can pose serious risks for drivers. Fog-related traffic accidents typically cause more deaths in the United States each year than other high-profile weather events like heat waves, tornadoes, and floods, according to data from the National Weather Service and the Federal Highway Administration. The foggiest parts of the United States, including Oregon, see dense fog at least 40 days per year.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Story by Michael Carlowicz and Adam Voiland.

View this area in EO Explorer

Oregon’s Willamette Valley had endured several long stretches of thick fog in January and February 2022 due to temperature inversions."

Source: NASA Earth Observatory

Remembering long drives to California in the distant past, Oregon was about 400 km of potential fog. This photo published last year brought back memories.

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

give us a life update. relationships, jobs, where you live, anything new, pets, tattoos, changes?

Loving this vibe check. I moved to Los Angeles proper 3 years ago and have been thriving living in a semi-walkable area and using decent public transit. I’ve grown to be super passionate about public transit and was just interviewed by NPR’s Southern California radio station earlier this year for a story on public transit trip cancellations in LA! It was super fun - it aired on the radio and they took my photo and everything lmao

I started a fully WFH job last year that I’ve been enjoying. I just won employee of the month in October and ngl it was really validating.

I’ve also become pretty passionate about the new earthquake early warning technology and worked with the U.S. Geological Survey at my old school district job to implement that technology at our schools. I’ll honestly preach to anyone I know in CA about downloading the early warning applications lol

I’ve been able to travel a lot in the past year to places like Japan, Toronto, and Vancouver. Hoping to keep the traveling streak going into next year (gotta make the most of my TSA pre check and global entry)

I got into cycling in 2020 and still love it. Here’s a recent photo from my first open streets event in LA where they close miles of streets to cars - along with an assortment of other pics since it’s been years since y’all got an update

#Unfortunately no new pets or tattoos (yet). Still single but very content with that rn.#Finally being in a city where I could access mental health care was a big win for my personal growth too#cutting off most of my family certainly helped too lol#Anyways - how is everyone else doing??

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Welcome to Ancient California-Gateway to Fu Shang

Bob Meistrell ran a scuba equipment shop in Palos Verdes. One day in 1975, he and his friend Wayne Baldwin were indulging their passion for diving and looking for lobsters and abalones to put on the barbeque back home. Although the fruits of the sea eluded them, their foray off the rocky reefs of the peninsula mainstream archaeology for years.

Spotting an unusual round object thirty-five feet down on the sea bottom, Meistrell and Baldwin hauled the thing, which turned out to be a 305-pound rock, to the surface and carted it back to the shop. The rock was almost perfectly round, with a circular hole bored in the center. In the next few weeks, they searched the area and eventually discovered about thirty-five more stones of similar appearance.

The artifacts soon came to the attention of James Moriarty III, a professor of history and archaeologist at the University of San Diego. After five years of research, Moriarty and his associate Larry Pierson concluded that the stones were anchors from an ancient shipwreck, possibly dating back some two thousand years. The largest object eventually brough to the surface weighed almost half a ton, leading the researchers to surmise that the ship it had come from was in excess of one hundred feet from stern to stern and may have carried a crew of fifty or more. The timbers of the ancient wreck had long since been battered to splinters on the treacherous coast of Palos Verdes peninsula. Through correspondence with scientists in Southeast Asia, Moriarty and Pierson deduced that the sandstone from which the anchors and ballast were fashioned was a type native to southern China. Although historians have began to take the idea of Chinese explorers more seriously in the last few years, at the time it was academic heresy to suggest that a non-European race had reached the shores of western North America almost 1,500 years before the Spanish made their first forays here in the sixteenth century. Mainstream archaeology massed to protect the status quo by first suggesting that the artifacts were merely leftover anchors from immigrant Chinese fishermen of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. But this explanation for the origin of the stones was refuted, since contemporary photographic evidence proved that the Chinese in California chose to employ readily available and much more practical metal anchors.

But that was not all that was found on the seabed near the Palos Verdes promontory: Two columnlike stones carved with grooves and holes, as well as a stone sphere weighing almost a ton with a groove cut around its circumference, were also recovered. No one could venture a guess as to what these objects were for and whence they came. Henriette Mertz, in her book Pale Ink, delved into the ancient Chinese legend of the land of Fu Shang. Although other scholars have found fault with her analysis, Mertz translated the old Chinese units of measure into miles and found that the tales of Fu Shang placed is location precisely at the California coast. Reading the stories told by the explorers, she also thought she recognized descriptions of Mount Shasta and the Grand Canyon.

The anchors found by Palos Verdes divers weren’t the first erratic Chinese artifacts to show up in America. A U.S. Geological Survey dredging operation had pulled up a similar object seventy-five miles off California’s coast. And earlier in the century, ancient Chinese inscriptions and relics had turned up in odd places around the West. Archaic Chinese rock writing had been found in a Nevada canyon, and a peculiar little idol covered with old Chinese characters was unearthed in Granby, Colorado: two more pieces in a vast, centuries-old Chinese puzzle.

For now, the academic battle still rages about the Palos Verdes artifacts. The anchor discovery may be the best challenge yet to orthodox American historians. For years, they have refused to believe that ancient Europeans and Africans had visited America before A.D. 1000, despite the Celtic stone cairns, Roman coins, and Phoenician urns that keep being uncovered on the New England coast. Now, from America’s western shore, comes a new affront to the continent’s “official” history: some doughnut-shaped stones tossed into the ocean two thousand years ago by Chinese sailors wrecked on the wave-lashed shores of Palos Verdes. It may take another generation for our school history books to catch up.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Speculation around Finland's 2024 presidential election is heating up, with media outlets increasingly reporting on potential contenders for the job.

An Ilta-Sanomat (siirryt toiseen palveluun) survey finds that Bank of Finland Governor Olli Rehn (Centre) and Foreign Minister Pekka Haavisto (Green) are still top of mind when it comes to replacing President Sauli Niinistö whose second term is coming to an end.

The poll's surprise news, however, was the appearance of Mika Aaltola on the list of favourites for president. Aaltola, who heads the Finnish Institute of International Affairs, has featured prominently in domestic media outlets since Russia invaded Ukraine.

"I can't recall anything similar happening before—a true dark horse. Aaltola's rating is incredible for someone not linked to party politics," Juho Rahkonen of pollster Taloustutkimus told IS.

Aaltola (32 percent) was ranked in the survey behind Rehn (49 percent), Haavisto (45 percent), Prime Minister Sanna Marin (SDP), 35 percent, and ex-PM Alexander Stubb (NCP), 34 percent.

Alive but declared dead

What's it like to deal with your own death? Readers of Hufvudstadsbladet (siirryt toiseen palveluun) have flocked to a story about Sipoo-based retiree Rita Tackman who, after a call to her bank, found out why her debit card kept being declined—the authorities had registered her as deceased.

The Swedish-language daily explains that a human error linked to Rita's visit to a local hospital set in motion a chain of events that has taken months to clear up.

"It has been a very difficult time. I’ve waited in numerous phone queues, filled in lots of paperwork and personally visited different agencies," she told HBL.

A 28,000-year battery?

Finland's deep geological repository for spent nuclear fuel, Onkalo, has made global headlines over the years as a way to deal with hazardous, radioactive waste.

But are there other solutions? Business daily Talouselämä (siirryt toiseen palveluun) reports of scientists recycling nuclear waste to create radioactive diamond batteries.

California-based startup NDB is planning to release a nano-diamond battery next year, according to TE, noting that the firm calculates that the batteries could last up to 28,000 years.

5 notes

·

View notes

Link

0 notes

Text

We Know Where The Next Big Earthquakes Will Happen — But Not When

Scientists Have Drastically Improved Our Understanding of Seismic Events. Here are Eight Things to Know.

— By Umair Irfan | April 5, 2024

A building lurches in Taiwan after a Magnitude 7.4 Earthquake Rocked the Island. Sam Yeh/AFP Via Getty Images

Earthquakes Can Strike When and Where We Least Expect Them — as residents in the New York City and New Jersey area discovered on Friday morning, when an estimated magnitude 4.8 quake hit at 10:23 am Eastern time.

The quake’s epicenter was in Lebanon, New Jersey, some 50 miles west of Manhattan, though shaking was reportedly felt as far south as Philadelphia and as far north as Boston. As of late Friday morning, there were no reports of serious damage.

Earthquakes on the East Coast are rare, but not unheard of. On August 23, 2011, a magnitude 5.8 quake struck nearly Mineral, Virginia, causing an estimated $200 to $300 million in damages. That quake occurred in the Central Virginia Seismic Zone.

In part because seismic waves can travel further in East Coast sediment than along the much more seismically-active West Coast, and because the region is so densely populated, scientists at the US Geological Survey estimated that the 2011 quake was likely felt by more people than any other quake in North American history.

Around the world, quakes remain a potent, deadly threat. The largest earthquakes in nearly 25 years rocked Taiwan on Wednesday morning, killing at least nine people and injuring hundreds more. The magnitude 7.4 quake led to a series of aftershocks, the largest of which reached magnitude 6.4. A series of earthquakes reaching magnitude 6.3 struck Afghanistan last year, leading to more than 2,400 deaths. A magnitude 6.8 earthquake rocked Morocco last September, the largest earthquake to hit the country in at least 120 years. Officials reported that it killed more than 2,900 people.

The Mediterranean region is also seismically active, according to the US Geological Survey, though such strong earthquakes are rare in North Africa. Quakes are more common in places like Turkey, where two major fault lines cross and trigger shocks on a regular basis. A huge magnitude 7.8 earthquake rattled across Turkey and Syria in 2023 and another quake with a magnitude of 7.5 rocked the region a few hours later. The quakes killed more than 50,000 people and toppled more than 5,600 buildings in the region.

While scientists have drastically improved their understanding of where earthquakes are likely to occur, forecasting when one will occur is still impractical. The rumbling earth can easily catch people off-guard, worsening the ensuing death and destruction.

In light of the recent disasters, here’s a refresher on earthquakes, along with some of the latest science on measuring and predicting them.

1) The Basics On What Causes Earthquakes

An earthquake occurs when massive blocks of the earth’s crust suddenly move past each other. These blocks, called tectonic plates, lie on top of the earth’s mantle, a layer that behaves like a very slow-moving liquid over millions of years.

That means tectonic plates jostle each other over time. They can also slide on top of each other, a phenomenon called subduction. The places on the planet where one plate meets another are the most prone to earthquakes. The specific surfaces where parcels of earth slip past each other are called faults. As plates move, pressure builds up across their boundaries, while friction holds them in place. When the former overwhelms the latter, the earth shakes as the pent-up energy dissipates.

Scientists understand these kinds of earthquakes well, which include those stemming from the San Andreas Fault in California and the East Anatolian Fault in Turkey. However, earthquakes can also occur within tectonic plates, as pressure along their edges cause deformations in the middle. These risks are harder to detect and measure.

“Our understanding of these within-plate earthquakes is not as good,” said Stanford University geophysics professor Greg Beroza. An earthquake within a tectonic plate has fewer telltale signs than those that occur at fault lines, he added.

2) The Richter Scale Isn’t The Only Measurement Game in Town Anymore

The Richter scale, developed by Charles Richter in 1935 to measure quakes in Southern California, has fallen out of fashion.

It uses a logarithmic scale, rather than a linear scale, to account for the fact that there is such a huge difference between the tiniest tremors and tower-toppling temblors. On a logarithmic scale, a magnitude 7 earthquake is 10 times more intense than a magnitude 6 and 100 times more intense than a magnitude 5.

The Richter scale is actually measuring the peak amplitude of seismic waves, making it an indirect estimate of the earthquake itself. So if an earthquake is like a rock dropped in a pond, the Richter scale is measuring the height of the largest wave, not the size of the rock nor the extent of the ripples.

And in the case of an earthquake, the ripples aren’t traveling through a homogenous medium like water, but through solid rock that comes in different shapes, sizes, densities, and arrangements. Solid rock also supports multiple kinds of waves. (Some geologic structures can dampen big earthquakes while others can amplify lesser tremors.)

While Richter’s scale, calibrated to Southern California, was useful to compare earthquakes at the time, it provides an incomplete picture of risks and loses accuracy for stronger events. It also misses some of the nuances of other earthquake-prone regions in the world, and it isn’t all that useful for people trying to build structures to withstand them.

“We can’t use that in our design calculations,” said Steven McCabe, leader of the earthquake engineering group at the National Institute of Standards and Technology. “We deal in displacements.”

Displacement, or how much the ground actually moves, is one alternative way to describe earthquakes. Another is the moment magnitude scale. It accounts for multiple types of seismic waves, drawing on more precise instruments and better computing to provide a reliable measuring stick to compare seismic events.

When you hear about an earthquake’s magnitude in the news — like Turkey’s recent magnitude 7.8 quake — moment magnitude is usually the scale being used.

But this is still a proxy for the size of the earthquake. And with only indirect measurements, it can take up to a year to decipher the scale of an event, like the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake, said Marine Denolle, an earthquake researcher at Harvard University.

“We prefer to use peak ground acceleration,” she said. This is a metric that measures how the speed and direction of the ground changes and has proven the most useful for engineers.

So, yes, earthquake scales have gotten a lot more complicated and specific over time. But that’s also helped scientists and engineers take much more precise measurements — which makes a big difference in planning for them.

3) We Can’t Really Anticipate Them All That Well

Predicting earthquakes is a touchy issue for scientists, in part because it has long been a game of con artists and pseudoscientists who claim to be able to forecast earthquakes. (Their declarations have, of course, withered under scrutiny.)

Scientists do have a good sense of where earthquakes could happen. Using historical records and geologic measurements, they can highlight potential seismic hot spots and the kinds of tremors they face. (You can check out the US Geological Survey’s interactive map of fault lines and NOAA’s interactive map of seismic events.)

As for when quakes will hit, that’s still murky.

“Lots of seismologists have worked on that problem for many decades. We’re not predicting earthquakes in the short term,” said Beroza. “That requires us to know all kinds of information we don’t have.”

It’s difficult to figure out when an earthquake will occur, since the forces that cause them happen slowly over a vast area but are dispersed rapidly over a narrow region. What’s amazing is that forces built up across continents over millions of years can hammer cities in minutes.

Forecasting earthquakes would require high-resolution measurements deep underground over the course of decades, if not longer, coupled with sophisticated simulations. And even then, it’s unlikely to yield an hour’s worth of lead time. So there are ultimately too many variables at play and too few tools to analyze them in a meaningful way.

Some research shows that foreshocks can precede a larger earthquake, but it’s difficult to distinguish them from the hundreds of smaller earthquakes that occur on a regular basis.

On shorter time scales, texts and tweets can actually race ahead of seismic waves. In the 2011 Tohoku earthquake in Japan, for example, warnings from near the epicenter reached Tokyo 232 miles away, buying residents about a minute of warning time.

Many countries are now setting up warning systems to harness modern electronic communications to detect tremors and transmit alerts ahead of shaking ground, buying a few precious minutes to seek shelter.

Meanwhile, after a large earthquake, aftershocks often rock the afflicted region. “If we just had a big one, we know there will be smaller ones soon,” Denolle said.

When it comes to prediction, researchers understandably want to make sure they don’t overpromise and underdeliver, especially when thousands of lives and billions of dollars in damages are at stake. But even this caution has had consequences.

In 2012, six Italian scientists were sentenced to six years in prison for accurately saying the risks of a large earthquake in the town of L’Aquila were low after a small cluster of earthquakes struck the region in 2009. Six days after the scientists convened to assess the risk, a large quake struck and killed 309 people. Those convictions were later overturned and the ordeal has become a case study for how scientists convey uncertainty and risk to the public.

4) Sorry, Your Pets Can’t Predict Earthquakes Either

Reports of animals acting strange ahead of earthquakes date back to ancient Greece. But a useful pattern remains elusive. Feathered and furry forecasters emerge every time there’s an earthquake and there’s a cute animal to photograph, but this phenomenon is largely confirmation bias. Animals do weird things (by our standards) all the time and we don’t attach any significance to them until an earthquake happens.

“On any given day, there will be hundreds of pets doing things they’ve never done before and have never done afterward,” Beroza said. Bottom line: Don’t wait for weird animal behavior to signal that an earthquake is coming.

5) Some Earthquakes are Definitely Human-made

The gargantuan expansion of hydraulic fracturing across the United States has left an earthquake epidemic in its wake. It’s not the actual fracturing of shale rock that leads to tremors, but the injection of millions of gallons of wastewater underground.

Scientists say the injected water makes it easier for rocks to slide past each other. “When you inject fluid, you lubricate faults,” Denolle said.

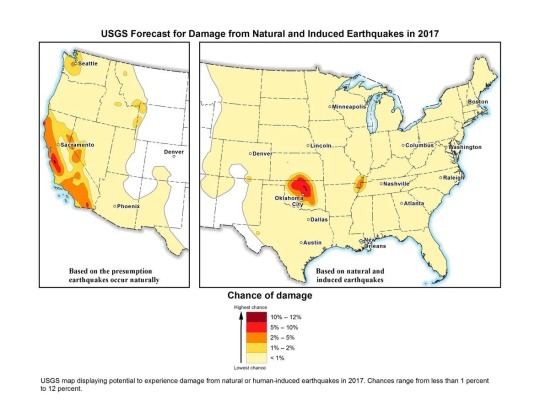

US Geological Survey map of natural and induced earthquake risk in 2017. USGS

The US Geological Survey calls these “induced earthquakes” and reported that in Oklahoma, the number of earthquakes surged to 2,500 in 2014, 4,000 in 2015, and 2,500 in 2016.

“The decline in 2016 may be due in part to injection restrictions implemented by the state officials,” the USGS wrote in a release. “Of the earthquakes last year, 21 were greater than magnitude 4.0 and three were greater than magnitude 5.0.”

This is up from an average of two earthquakes per year of magnitude 2.7 or greater between 1980 and 2000. (“Natural” earthquakes, on the other hand, are not becoming more frequent, according to Beroza.)

Humans are causing earthquakes another way, too: Rapidly drawing water from underground reservoirs has also been shown to cause quakes in cities like Jakarta, Denolle said.

6) Climate Change Could Have a Tiny Effect on Earthquakes

In general, scientists haven’t measured any effect on earthquakes from climate change. But they’re not ruling out the possibility.

As average temperatures rise, massive ice sheets are melting, shifting billions of tons of water from exposed land into the ocean and allowing land masses to rebound. That global rebalancing could have seismic consequences, but signals haven’t emerged yet.

“What might occur is enough ice melts that could unload the crust,” Beroza said, but added there is no evidence for this, nor for which parts of the world will reveal a signal. Denolle agreed that this could be a mechanism, but if there is any impact from climate change on earthquakes, she says she suspects it will be very small.

7) We’ve Gotten Better at Reducing Earthquake Risks and Saving Lives

About 90 percent of the world’s earthquakes occur in the Ring of Fire, the region around the Pacific Ocean running through places like the Philippines, Japan, Alaska, California, Mexico, and Chile. The ring is also home to three-quarters of all active volcanoes.

Most of the planet’s earthquakes occur along the Pacific rim in a region known as the Ring of Fire. Javier Zarracina/Vox

Mexico is an especially interesting case study. The country sits on top of three tectonic plates, making it seismically active. In 1985, an earthquake struck the capital, killing more than 10,000. Denolle noted that the geology of the region makes it so that tremors from nearby areas are channeled toward Mexico City, making any seismic activity a threat.

The Mexican capital is built on the site of the ancient Aztec city of Tenochtitlan, an island in the middle of a lake. The dry lakebed that is now the foundation of the modern metropolis amplifies shaking from earthquakes.

The 1985 earthquake originated closer to the surface, and the seismic waves it produced had a relatively long time between peaks and valleys. This low-frequency vibration sends skyscrapers swaying, according to Denolle. “The recent earthquakes were deeper, so they had a higher frequency,” she said.

The biggest factor in preventing deaths from earthquakes is building codes. Designing buildings to move with the earth while remaining standing can save thousands of lives, but putting them into practice can be expensive and frequently becomes a political issue.

“Ultimately, that information has got to get implemented, and you can pretty much get that implemented in new construction,” McCabe said. “The trickier problem is existing buildings and older stock.”

Earthquake-prone countries know this well: Japan has been aggressive about updating its building codes regularly to withstand earthquakes. The revised standards have in part fueled Japan’s construction boom despite its declining population.

Mexico has also raised standards for new construction. Laws enacted after the 1985 earthquake required builders to account for the soft lakebed soil in the capital and tolerate some degree of movement.

Meanwhile, Iran has gone through several versions of its national building standards for earthquake resilience. And Alaska has been developing earthquake damage mitigation strategies and response plans for years.

But codes are not always enforced, and the new rules only apply to new buildings. A school that collapsed in a 2017 Mexico City earthquake apparently was an older building that was not earthquake-resistant. And because the more recent earthquakes in Mexico shook the ground in a different way, even some of the buildings that survived the 1985 earthquake collapsed after tremors in 2017.

In countries like Iran, there is a wide gulf between how buildings are constructed in cities versus the countryside. More than a quarter of the country’s population lives in rural areas, where homes are built using traditional materials like mud bricks and stone rather than reinforced concrete and steel. This is a big part of why casualties are so high when earthquakes strike remote parts of the country.

The biggest risks fall to countries that don’t have a major earthquake in living memory and therefore haven’t prepared for them, or don’t have the resources to do so. A lack of a unified building code led to many of the more than 150,000 deaths in Haiti stemming from the 2010 magnitude 7.0 earthquake.

8) The Big One Really is Coming to the United States (Someday)

The really big one you keep hearing about is real.

The New Yorker won a Pulitzer Prize in 2015 for its reporting on the potential for a massive earthquake that would rock the Pacific Northwest — “the worst natural disaster in the history of North America,” which would impact 7 million people and span a region covering 140,000 square miles.

The potential quake could reach a magnitude between 8.7 and 9.2, bigger than the largest expected earthquake from the San Andreas Fault, which scientists expect to top out at magnitude 8.2.

Large earthquakes are also in store for Japan, New Zealand, and other parts of the Ring of Fire. We don’t know when these earthquakes will rock us; we just have a rough estimate of the average time between them, which changes from region to region.

“In the business, we’ve been talking about that [Pacific Northwest] scenario for decades,” Beroza said. “I wouldn’t say we’re overdue, but it could happen at any time.”

“It is a threat,” echoed Denolle. “We forget about this threat because we have not had an earthquake there for a while.” “A while” means more than 300 years.

So while California has long been steeling itself for big earthquakes with building codes and disaster planning, the Pacific Northwest may be caught off guard, though the author of the New Yorker piece, Kathryn Schulz, helpfully provided a guide to prepare.

— Umair Irfan is a correspondent at Vox writing about climate change, Covid-19, and energy policy. Irfan is also a regular contributor to the radio program Science Friday. Prior to Vox, he was a reporter for ClimateWire at E&E News.

0 notes

Text

Earthquakes centered near Belden rattle Northern California

BELDEN – Shaking was felt all across Northern California after two earthquakes centered near the small town of Belden on Thursday evening.

The United States Geological Survey (USGS) website reports a preliminary 4.5 and a preliminary 4.3 earthquake just after 6:30 p.m. The depth of one earthquake was about six miles.

A third earthquake struck at about 7 p.m. with a preliminary magnitude of…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Today in History: Today is Tuesday, March 26, the 86th day of 2024.

By The Associated Press

Today’s Highlight in History:

On March 26, 1997, the bodies of 39 members of the Heaven’s Gate techno-religious cult who committed suicide were found inside a rented mansion in Rancho Santa Fe, California.

On this date:

In 1812, an earthquake devastated Caracas, Venezuela, causing an estimated 26,000 deaths, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

In 1827, composer…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

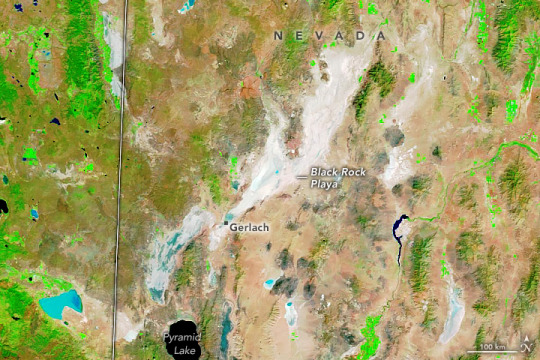

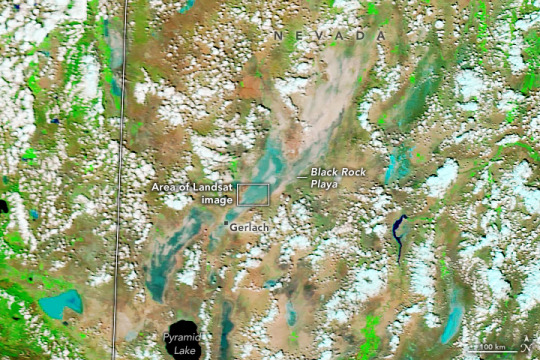

Summer Rains on Nevada’s Black Rock Playa

Campers at Burning Man, an annual arts festival in Nevada’s Black Rock Desert, might typically expect to bake in the late summer sun on a dusty playa. In September 2023, however, attendees encountered a bout of unusually heavy rain that turned the pancake-flat desert basin into a sea of mud.

This image pair shows the desert on August 26 (top image), the day before the festival began, and on September 4 (lower image), after several months’ worth of rain had fallen in the preceding days. The images use false color to make it easier to distinguish the presence of water. Saturated ground, silty water, and lakes appear in shades of blue, and vegetation is bright green. They were acquired by the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Terra satellite.

The image below, also acquired on September 4, shows a detailed view of the area in natural color. Dark areas are likely mud, or where the surface is saturated with water. The image was acquired with the Operational Land Imager-2 (OLI-2) on Landsat 9.

Since 1990, festivalgoers have constructed a temporary settlement in the Black Rock Desert in late August and early September for the Burning Man gathering. The 2023 version of the camp is visible in the Landsat image above. It is situated in the middle of the Black Rock Playa, a flat, featureless expanse stretching northeast from the town of Gerlach for more than 30 miles (50 kilometers). The playa is a remnant of a large prehistoric lake, Lake Lahontan, which filled in a large portion of the Great Basin over 15,000 years ago.

In present times, rainfall along with snowmelt from surrounding mountains gathers into shallow pools on the playa in winter and early spring. With nowhere to go, the water feeds an aquatic ecosystem that includes fairy shrimp, tadpole shrimp, and water fleas. Typically, the water evaporates in warmer, drier months, leaving behind a solid surface. However, there have been recent exceptions to the seasonal cycles, when the playa has stayed dry in the winter months or wet in the summer.

On September 1, 2023, up to 1 inch (25 millimeters) of rain fell on the playa, according to news reports. On average, the area receives about 6 inches (150 millimeters) per year, with only 0.2 inches (5 millimeters) falling in September. The unseasonable rains were enough to transform the hard-packed desert floor into a muddy slurry in the middle of the Burning Man festival. By the morning of September 3, the surface was still too wet to drive on, according to updates issued by Burning Man, and additional drizzle and cloud cover slowed the drying-out process. By midday on September 4, tens of thousands of festivalgoers remained on the playa but were able to start driving out that afternoon.

The early-September storms in Nevada caused flooding in other parts of the state. Las Vegas received 0.88 inches (22 millimeters) of rain on September 1, a record amount for that day. Heavy rains triggered flash flooding in the city and forced the closure of Interstate 15 near the California-Nevada border.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Michala Garrison, using MODIS data from NASA EOSDIS LANCE and GIBS/Worldview, and Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Story by Lindsey Doermann.

3 notes

·

View notes