#The Tragedy of American Science

Quote

Siri was a product of a DARPA program called PAL, “Personalized Assistant that Learns,” the largest AI research project in American history. In DARPA’s own words, PAL’s mission was “to make military decision-making more efficient and more effective.” It also, however, “led to the 2007 launch of Siri Inc., later acquired by Apple Inc., which further advanced and then integrated the Siri/PALtechnology into the Apple mobile operating system.”

Clifford D. Conner, The Tragedy of American Science: From Truman to Trump

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

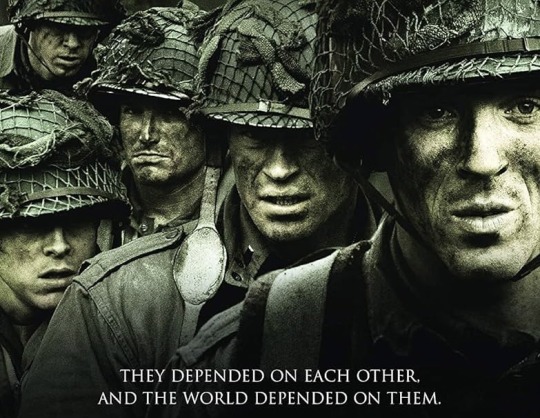

'WHO WAS J. Robert Oppenheimer? This is easy enough to answer: an American theoretical physicist, the “father of the atomic bomb,” an important architect of early US nuclear policy, and, ultimately, a victim of anti-communist fervor after he lost his security clearance in a well-publicized decision by the Atomic Energy Commission in 1954 and was excommunicated from the nuclear priesthood. Oppenheimer’s very public rise and fall, and his embodiment of various parables about dangerous knowledge (Faust, Prometheus, Icarus, etc.), have made his life one of the most scrutinized and publicized in the history of modern science. And yet, he is still universally described as inscrutable despite an extraordinary wealth of documentation: a voluminous FBI file; a security hearing that picked over his life with a microscope; and an archive of letters, memos, and recollections of both friends and enemies.

Some of Oppenheimer’s affect was clearly deliberate—he consciously played the role of a worldly, “brilliant” intellectual with broad-ranging interests and a rapid-firing mind. His close friend, the physicist I. I. Rabi, later told physicist and historian Jeremy Bernstein that “[Oppenheimer] lived a charade, and you went along with it.” The interest in Hindu philosophy and scripture, the Sanskrit, the cowboy-rancher, the poet, the flirtations with communism, the reading of Das Kapital in the original German—this was “Oppie,” a character invented by an insecure young man in the 1920s who struggled to be taken seriously by the luminaries he admired, and who felt a deep need to leave behind his cushy German Jewish upbringing on the Upper West Side.

That Oppenheimer himself played a role makes it especially fitting that his life has been adapted not only into a dozen or so full-length biographies but also in far more general histories of the atomic bomb and many prominent fictional portrayals in film, television, graphic novels, and one opera. (The best study of Oppenheimer’s use as a narrative figure is David K. Hecht’s 2015 book Storytelling and Science: Rewriting Oppenheimer in the Nuclear Age.) And while he has been subjected to the Hollywood treatment several times before, he has perhaps never been granted as much artistic treatment, nor quite such an enormous filming budget, as he has this summer with the debut of Oppenheimer, the latest film by Christopher Nolan.

Nolan wrote, directed, and produced Oppenheimer, explicitly basing it largely on the Pulitzer Prize–winning biography American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer (2005), written by Kai Bird and the late historian Martin J. Sherwin. Nolan clearly fell into the Oppenheimer rabbit hole and, one can surmise, became captivated by the challenge of how to represent his paradoxical mind. What has resulted from that fascination is plainly a labor of love, both for Nolan and his leading actor, Cillian Murphy. According to Nolan’s promotional interviews, the script was written exclusively in the first person—from Oppenheimer’s perspective—a remarkable and telling revelation about the questions Nolan was pursuing. The film is fast-paced, with short, quick-cut scenes that proceed out of chronological order over a very long running time; a sense of anxious dread hangs over the entire affair. Oppenheimer is not easy to watch, and the large number of A- and B-list actors playing small roles (as historical figures both famous and obscure) is distracting and, at times, confusing, even for someone who knows the historical source material.

And yet, improbably, the film has become a summer blockbuster: within a few weeks, it reportedly earned several multiples of its purported $100 million price tag. As Variety put it, “considering ‘Oppenheimer’ is a three-hour, R-rated biographical drama, these numbers are staggering.” Much of this can be credited to Nolan, almost universally acknowledged as the premier director working at the intersection between think piece and spectacle.

When I learned that Nolan was making an Oppenheimer film, the first question that came to mind was: why? None of Nolan’s other films suggested an interest in historical biography, and if anything, the most frequent critique of Nolan is his indifference to deep characterization. Since I have been thinking about J. Robert Oppenheimer for some 20 years, I can certainly understand his allure, but to Nolan? I worried that Oppenheimer’s inner complexity and subtlety, the very thing that historians find interesting about him, would be turned into a simplistic parody (the brilliant scientist, the weeping martyr, the weapons maker, etc.).

And so, upon watching the film, I was impressed by how much Nolan as writer, and Murphy as actor, tried to avoid this particular snare. Murphy’s Oppenheimer exudes tension, intelligence, and, crucially, insecurity. He is not portrayed as a hero, or someone you would want to emulate, or potentially even someone you would like to have dinner with. He is smart, yes, but he’s also a show-off, a know-it-all whose need to be considered “brilliant” by others drives him at times to be impressive, cruel, and thoughtless. It is remarkable that Nolan and Murphy went in this direction. One gets the sense that Nolan thinks Oppenheimer is important, and interesting, but not that he likes Oppenheimer. This may have helped him avoid the most seductive trap of all: trying to make Oppenheimer a relatable everyman.

The film zigs and zags temporally, using Oppenheimer’s 1954 security clearance hearing as an organizer of sorts, jumping between 1954 and various moments from Oppenheimer’s earlier life. There is also some footage, always in black-and-white to distinguish it from Oppenheimer’s point of view, that follows the perspective of Lewis Strauss (played with verve by Robert Downey Jr.), Oppenheimer’s political enemy and the architect of his security clearance revocation. A few periods in Oppenheimer’s life receive particular focus: his early years as a student in Cambridge (ca. 1925), his years as a young professor at the University of California, Berkeley (1930s), the years he worked on the Manhattan Project (1942–45), the detection of the Soviet atomic bomb and the debate over the hydrogen bomb (1949–50), and the turn in political fortunes that led to his security clearance hearing and revocation (1953–54). Though this leaves out some key periods in his biography (more on that in a moment), it still feels like a lot to cover in a single film—too much, perhaps.

As a historian of nuclear weapons, I have been asked innumerable times since the film came out whether it was accurate. It is a harder question to answer than one might think. At some level, the answer is “of course not”—but that is true of not only all historical films but also, to a certain degree, all historical books. “Truth” is a tricky thing in general, and “historical truth” even trickier; scholars are always finding fault with each other’s works, and there is never any real consensus on the true character of a historical figure even for people with less apparent depth than Oppenheimer. And then there’s the fact that the standard for works of art is surely different. In Oppenheimer, many of the characters’ lines are in fact taken from historical documents, sometimes verbatim. When David Krumholtz delivers Rabi’s famous line about being appreciative of Oppenheimer’s contributions (“and what more do you want, mermaids?”), he uses an unusually verbatim quote, including a section (“and a whole series of Super bombs”) that was redacted until 2015, and is not present in any Oppenheimer biography that I know of.

The film also contains tricky mixtures of real and wholly imagined dialogue. In his testimony at Oppenheimer’s hearing, General Leslie Groves (Matt Damon), the military head of the Manhattan Project, concedes that, had he been acting according to the standards of the postwar Atomic Energy Act during World War II, he would not have given Oppenheimer a security clearance. This is indeed in the transcript of the security hearing. But in the film, Groves shoots off one more line, to the effect that he wouldn’t have cleared any of the scientists by that standard. It’s a good line—but the real Groves never said it, nor did he imply it in his actual testimony. Though supportive of Oppenheimer, he was also shielding himself from his own political and legal vulnerabilities. But the sentiment is right for the film, serving as an indication that Groves bore Oppenheimer no ill feeling, and that the priorities and requirements of World War II were different from those of the Cold War.

More troublesome are the aspects of the film that are based on untrustworthy historical accounts. A terrific scene, which takes place just after Hiroshima, shows Oppenheimer giving a rousing and patriotic speech to a bloodthirsty crowd while internally haunted by thoughts of the burned and dead. It is the one place where Oppenheimer’s conflicting feelings toward Hiroshima are portrayed, and where what had happened at Hiroshima is imagined.

The scene is powerful and appropriately disturbing. You could hear a pin drop during this scene in the sold-out theater I attended. But did this particular speech actually happen? It was not invented whole cloth by Nolan; the setup and dialogue were taken from a scientist’s recollections. But the scientist in question, Samuel Cohen, is the only person who has ever indicated that this event happened, and he only wrote it down many decades after the fact. (In his self-published memoir, Cohen insinuates that “[t]here’s an explanation” for the fact that nobody has ever written about this other than himself, but that he couldn’t be bothered to write about it.) Cohen was a bit of a fabulist; he created an identity for himself as the “father of the neutron bomb” based on work he did on the possibilities of enhanced-radiation warheads at the RAND Corporation in the late 1950s, which actual weapons designers from the period regarded as fairly insignificant. He was also no fan of Oppenheimer’s, considering him “a real sadist.” I do not put much stock in Cohen’s story.

But one can see the appeal of such a scene for Nolan: no other accounts have Oppenheimer giving any such speech after Hiroshima, or doing anything other than perhaps going to one party and then leaving. The literal or hewing-to-the-facts approach would be anticlimactic—whereas incorporating Cohen’s account allows for a complex exploration of the American reaction to Hiroshima, the Los Alamos reaction to Hiroshima, and Oppenheimer’s reaction to Hiroshima. It gives Nolan and Murphy a broader canvas to work with. Is there a greater truth being expressed, whatever the quality of the source? I am not sure. It depends on what one believes about Oppenheimer’s mental state immediately after Hiroshima, before the accounts of casualties and suffering came in, before Nagasaki, and before he was enlisted to (erroneously, it turns out) deny Japanese reports of radiation sickness. (Michael D. Gordin’s 2007 book Five Days in August: How World War II Became a Nuclear War is a close account emphasizing just how rapidly attitudes on the atomic bomb changed in the days between its first use and the eventual surrender of Japan.)

Another example of Hollywood invention occurs when Nolan has Oppenheimer meet President Harry Truman, and the president calls Oppenheimer a “crybaby” for complaining about having blood on his hands. What is the source of these insults? The “crybaby” and “blood” bits come from later stories told by Truman, when he was trying to impress upon others how impractical and irritating scientists can be, and how it was he, Harry Truman, who truly had blood on his hands (Truman had his own complex relationship to the bombings, despite his tough talk). There is also an account from biographer Nuel Pharr Davis of Oppenheimer’s side of that story, but Davis provides no citation whatsoever, nor even a date when this conversation may have taken place.

Nolan also interpolates into this meeting a line in which Oppenheimer suggests that the future of Los Alamos should be to “give it back to the Indians.” Not only is this unlikely to be a true line—a sentiment to the contrary is more likely—but also the only person who might have suggested that Oppenheimer said this was Edward Teller (another Oppenheimer enemy), and only in 1950 as part of an explicit attempt to recruit opposition to Oppenheimer and lobby for Teller’s own weapons laboratory (which would eventually become Livermore). As the late Oppenheimer biographer Priscilla McMillan pointed out, “Give It Back to the Indians” was a popular show tune from 1939, and if Oppenheimer ever did say the phrase, it was probably in jest, and certainly not to the president. (My wife has suggested that this would be like hearing someone describe themselves as a “Gangster of Love” and interpreting it as a literal assertion, rather than a tongue-in-cheek reference to the Steve Miller Band.) In Teller’s actual testimony at Oppenheimer’s security hearing, Teller distanced himself from the line, claiming that he heard it “attributed to Oppenheimer” but could not recall ever hearing him say it.

The film is full of such questionably accurate scenes. Did Oppenheimer actually try to poison his tutor at Cambridge with a poisoned apple? We don’t really know. Young Oppenheimer, as reflected through his letters of the period, was prone to making exaggerated, “shocking” statements of this sort. (Many of Oppenheimer’s letters from the 1920s contain what Jeremy Bernstein refers to as “Oppenheimer exuberance.”) It makes for a more perplexing character portrait to imagine these moments as literal, as Nolan does in the film, which raises this question: is representing them as literal truth getting at a deeper truth, or introducing a deeper confusion? Does the ambivalence of historians about an event give the artist full latitude to present it either way?

The most shocking (and creative) reappropriation is the famous line from the Bhagavad Gītā that Oppenheimer later claimed flashed into his mind during the world’s first nuclear test, Trinity: “Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.” The actual line is an idiosyncratic translation, deployed as a near incomprehensible (and perhaps pretentiously “Oppie”) analogy about duty and awe. Disregarding whatever the real Oppenheimer might have meant by it, Nolan’s film turns the quote into an orgasm, or a memory of an orgasm. There is something about this kind of transformation that I respect more than the subtler ones.

Nolan is most editorial when he invents lines about Oppenheimer’s motivations and mental state and puts them into the mouths of observers: Haakon Chevalier (Jefferson Hall) suggests that Oppenheimer’s difficulties as a parent (and perhaps as a person) might be the result of staring into the infinite void of the universe for too long; Kitty Oppenheimer suggests that her husband’s need for the security hearing is a form of penance for his guilt about Hiroshima (an interesting thesis, one he surely would not have agreed with, but who knows?); Strauss suggests that Oppenheimer would like the world to remember him for Trinity, not Hiroshima (also interesting, although putting interesting sentiments into the mouth of a sworn enemy and unreliable narrator tends to dilute their credibility). I might not agree with these interpolations, but I respect that they are not superficial “theses” about Oppenheimer. That Murphy’s character does not endorse or deny any of them is, I think, a plus: the film suggests them as possible interpretations but does not collapse the uncertainty into one definitive reality.

Nolan’s film is most directly misleading about actual history when Oppenheimer is portrayed as getting sidelined, starting at the end of the Los Alamos sequence when it is suggested that, despite his usefulness to the military and the government, they are only interested in Oppenheimer’s technical abilities and not in his advice on other matters. It is further implied that in the film’s postwar period, Oppenheimer becomes marginalized, in part because Strauss is the sort of person who actually controls policy. This is wrong on several levels. Oppenheimer was much closer to the policy process during World War II than the film depicts, including in the targeting of the atomic bombs (and not just from a technical perspective). The film’s implication of distance between Oppenheimer and the government officials involved in dropping the atomic bomb is inaccurate; they all saw eye to eye, and Oppenheimer personally endorsed the idea that the bombs ought be dropped on “urban areas” without warning. He even suggested, after the Trinity test, ways in which the bomb designs could be modified to use more of their scarce nuclear fuel, so that there would be many more bombs ready to drop on Japan (Groves rejected this suggestion for the first bombs). Many years later, well after Oppenheimer had died, Strauss told an interviewer that these scientists during World War II felt a “compulsion to use the bomb—an obsession,” and while one should be wary of the source, in this case I think he was right.

In truth, Oppenheimer enjoyed tremendous influence in the atomic energy establishment after World War II. The chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission for its first, formative years was not Strauss but David Lilienthal, a liberal New Dealer who considered himself a close friend of Oppenheimer’s and a political ally. Oppenheimer’s views did not always carry the day, but one cannot really describe him as sidelined until Eisenhower became president in 1953, and then only because Strauss was made AEC chairman (Strauss’s anti-Oppenheimer campaign, whatever its deep motivations, began in earnest when he feared that Eisenhower would be charmed by Oppenheimer’s way of thinking). One can see how this makes a less clean narrative about Oppenheimer and early nuclear policy, and one can see as well why Nolan probably felt that jumping from 1945 to 1949 worked better for an already long film.

There are other areas where the film’s limited bandwidth creates distortion. The reactions to both the first Soviet atomic test and the hydrogen bomb debate feel rushed and devoid of stakes. One does not get a sense of what the H-bomb debate was about, or why people who supported building the atomic bombs would find the H-bombs morally objectionable. The brief section that addresses the plans for using the atomic bombs in Japan reinforces narratives that historians have for decades known to be false (like the idea that it was seen as a question of “bomb or invade”—in reality, these were not considered alternative options, and it was not at all clear that one, two, or even more atomic bombs would end the war). (Groves told Oppenheimer after Trinity, for example, “It is necessary to drop the first Little Boy and the first Fat Man and probably a second one in accordance with our original plans. It may be that as many as three [Fat Man bombs] may have to be dropped to conform to planned strategical operations,” along with the Little Boy bomb.) One gets the sense that these are not the kinds of historical questions that Nolan cares about.

So what does the director care about? Why make a film about Oppenheimer at all? Cold War narratives about Oppenheimer tend to be moralizing parables about the dangers of McCarthyism and the security state. This is not Nolan’s interest; to his credit, he makes it very clear that though the Oppenheimer hearings were a farce as far as justice was concerned, once the scientist’s behavior was under the microscope, it became hard for anyone, including Oppenheimer, to justify it. Oppenheimer might have gotten to his precarious position because he offended a few powerful people, and because he opposed them on the question of thermonuclear weapons, but his fate was sealed by his admission that he had lied repeatedly to security officers and had maintained connections—even sexual ones—with known or suspected communists after becoming the head of Los Alamos. One doesn’t leave Nolan’s film concerned that Oppenheimer didn’t get justice.

Nolan’s interest in Oppenheimer centers on two themes. One of them is the complexity of Oppenheimer’s character. The other is global destruction, threaded through the entire film from its first images until its last scene. The fact that these two themes are intertwined in the same person is, I think, the point. In Oppenheimer, the intensely personal is suffused with the apocalyptic imagination. The visions that kept Oppenheimer up at night were not about Hiroshima and Nagasaki, for better or worse. They were about the next war, the one he hoped Hiroshima and Nagasaki would make impossible.

When Secretary of Commerce Henry Wallace met Oppenheimer a few months after the end of World War II, he described a man in great distress. “I never saw a man in such an extremely nervous state as Oppenheimer,” Wallace wrote in his diary. “He seemed to feel that the destruction of the entire human race was imminent. […] The guilt consciousness of the atomic bomb scientists is one of the most astounding things I have ever seen.” (The result of this meeting was Wallace’s arranging of Oppenheimer’s disastrous encounter with Truman in the Oval Office.) Oppenheimer was, at this point, desperately trying to advocate for a world in which no nation would have nuclear weapons, using the horrors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the nascent plans for even worse weapons, as an impetus for remaking the entire nature of war and international relations. He did not succeed; we live in his worst nightmare, where multiple states have civilization-killing quantities of nuclear arms ready for deployment at a moment’s notice.

This harried, eschatological prophet, desperately trying to invoke what influence he has in order to convince the people with real power not to use that power poorly, is the Oppenheimer that Murphy channels, and that Nolan is interested in. I have always thought that Prometheus was the wrong reference point, one that Oppenheimer himself would have strongly rejected. Oppenheimer was no champion of humanity, and his punishment was not for having “stolen fire,” but for more mundane transgressions, including those of the flesh, a fact that Nolan’s film emphasizes. In his Bhagavad Gītā reference, Oppenheimer renders himself as Prince Arjuna, who was cajoled by something great and terrible into taking on a burden he did not want. Even that feels incomplete, for while Oppenheimer was initially willing to go to war, he was afterwards gripped with an intense desire to push things in a different direction. Perhaps we need to invent a new, modern mythology for such a figure; perhaps that is what Nolan is really trying to do. Let’s hope the film will be remembered for this, and not just for its curious juxtaposition with the other summer blockbuster, Greta Gerwig’s (excellent) Barbie.'

#Christopher Nolan#Cillian Murphy#Edward Teller#Oppenheimer#Leslie Groves#Bhagavad Gita#Atomic Energy Commission#Isidor Issac Rabi#Jeremy Bernstein#Greta Gerwig#Barbie#American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer#Kai Bird#Martin J. Sherwin#Robert Downey Jr.#Lewis Strauss#The Manhattan Project#Storytelling and Science: Rewriting Oppenheimer in the Nuclear Age#David K. Hecht#Matt Damon#Los Alamos#Michael D. Gordin#Five Days in August: How World War II Became a Nuclear War#President Harry Truman#Nuel Pharr Davis#Priscilla McMillan#Haakon Chevalier#Jefferson Hall#Kitty#Trinity test

1 note

·

View note

Text

youtube

#robert oppenheimer#physicist#quantum#trinity#bomb#atomic bomb#america#history#tragedy#American Prometheus#world#movie#2023#science#lessons#peace#world war 2#film#trailer#Youtube#Christopher Nolan

0 notes

Text

Terror Camp 2023's Panel Lineup Announcement is here!

We are so excited to hear from all of these amazing presenters over two days in December 🤩👏

Posters, artists alley tablers, and keynote speakers will be announced over the next few weeks, as well as the link to RSVP, so make sure you sign up for our mailing list on our website!

Without further ado:

Terror Day - Saturday, December 9

Panel A: Primary Sources

"old Harvey (a mulatto)": Sailors of Colour on British Arctic Expeditions (1848-1859), Edmund Wuyts

"Do attend to your orthography": spelling as history in Franklin Expedition Letters, Reg

Relic or Artefact; an Analysis of Polar Artefacts in Museum Catalogues, Ash

Panel B: Historical Persons

Thomas Holloway: Pills, Palaces, and The Accursed Bears, Verity Holloway

"Scarface" Charley Tong Sing: A Chinese-American on the Jeannette, In the Papers, and Afterwards, Han

Failsons of Hudson Bay, Jas Bevan Niss

“Nor will it yield to Norway or the Pole”: Roald Amundsen as Shakespearean Tragedy, Ireny

Panel C: Cultural Understandings and the Arctic

How Fares the Raft of the Medusa?: Mutiny, Cannibalism, and the Portrayal of History, Brianna Lou

“This Place Wants Us Dead”: The Terror and Folk Horror, Allison Raper

Icebound, Not Down, Hester Blum

Erebus Day - Sunday, December 10

Panel D: Death and Narratives of Death

"Known to all the youth of the Nation": Scott's Sacrifice in Children's Literature, Branwell

What We Talk About When We Talk About Quest, Caitlin Brandon

Funny to think of it as coming home: football, exploration, and the stories we tell ourselves, Rach

Panel E: The Allure of the Antarctic

From the South Pole to the Stars, Emma

The Feminine(?) Antarctic, Sam Botz

There and Back Again: In the Antarctic with Ross and Crozier, Phil Mikulski

Antarctic Roundtable

Out of the Rookery: An exploration of science and survival on Shackleton's Endurance, with Rebecca, Meg, and Avery

156 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Fairy Garden

My Ko-Fi

Commission Directory

My Art Tag: tin art

My ask box and DMs are always open for people to come chat or be horny little freaks!

Don't like it? Don't consume it!

Don't be a cunt.

Dark content including rape, self harm, suicide, domestic violence, drug and alcohol abuse, necrophilia, cannibalism, incest and bodily fluids will be present here.

My only major boundary is scat. It just doesn't interest me.

Bestiality and pedophilia are entirely off the table. Yuck.

I do not consent to my writing or art being translated and/or posted to any other website or being fed to AI.

I go by Tin or Lu, I'm 22 years old.

Filthy American 🦅*eagle noises*

I am non-binary more fem leaning. I use any pronouns but use she/her by default since it's just easiest.

I use the terms 'boy, man, guy' etc. for myself a lot so feel free to do so as well.

I represent myself with bears and orange cats.

About Lu

Lu is similar to an alter ego or imaginary friend if you will. I blame shit on him and project my problems onto him. I use him so I don't have to feel negative emotions. He is my punching bag.

Lu is me and I am Lu and I am in full control of my actions and words.

Lu is represented by black dogs/wolves

Fun Facts

I have 2 kitties named Mercury and Jasmine and 2 leopard geckos named Mister Man and Dracarys

I do lots of art, I used to write a lot but I haven't had the muse for it lately

Mentally ill but who isn't these days (we live in a society fr)

Kink Stuff

Bisexual, switch. Lots of nasty, icky kinks.

A mommy dom, or a ma'am but I like being called daddy and sir too. I love puppy and kitty subs and littles.

I am a kitty sub and a little sometimes.

I like being a brat.

I can be a mean dom or soft dom depending on what my sub wants

Fandom List

(this list updates frequently and you're always welcome to pop into my ask box or DMs to talk about these fandoms!)

Anime/Cartoons: Hunter x Hunter, Death Note, Fruits Basket, One Piece, Black Butler, Hazbin Hotel, Jojo's Bizarre Adventure, Ouran High School Host Club, Princess Jellyfish

TV Shows: Supernatural, The Boys, Gen V, Alice in Borderland, Game of Thrones, House of the Dragon, Criminal Minds, Percy Jackson

Movies: Lord of the Rings, The Hobbit, The Hunger Games, The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes, MCU, DCU, X-Men, Slasher/Horror Fandom, Star Wars, The Last Unicorn, Repo! The Genetic Opera, Twilight Saga, Phantom of the Opera, Sweeney Todd

Video Games: Left 4 Dead, Fallout, Mass Effect, Dragon Age, Borderlands, Resident Evil, Dead By Daylight, Stardew Valley, Red Dead Redemption, Animal Crossing, Sally Face, Fran Bow, Night in the Woods

Misc: Creepypasta, Marble Hornets, Homestuck, Boyfriend to Death, The Price of Flesh, The Vampire Chronicles

Other Interests

Art, writing, history, archeology, anthropology, architecture, vintage era, edwardian era, medieval era, dinosaurs, cryptozoology, speculative evolution, science, mass tragedies, chernobyl meltdown, cults, fashion, historical fashion, horror, true crime, music, musicals

My Hunger Games/TBOSAS Masterlist

My One Piece Masterlist

My Hunter x Hunter Masterlist

My Old Masterlist

749 notes

·

View notes

Text

Exordia - advance review

So. I finished the book!

This is not everything I will write about Exordia. That will come when the book is like, officially out, and I feel comfy spelling out the ending and quoting passages at length.

This 'advance review' is split into two parts. The first part is quite abstract, so I'll copy it here.

If Baru took an elliptical path towards its subject matter, by defamiliarising and rearranging the material of history… Exordia just gets straight in there.

How to describe Exordia? Maybe you could call it philosophy-driven science fiction, a thought experiment about ethics. Maybe you could compare it to Arrival, but shot up with black humour (it’s a book that could make me laugh and cry, sometimes at the same time) and real tragedy (at the core is the genocide of the Kurds in the late 80s, and the many betrayals and failures of American imperialism). It’s got a lot of action and military details, with a good few spies and soldiers as central characters, but broadly it’s one of the sharpest eviscerations of the US military and its role in the world I’ve encountered in Western science fiction.

The first two thirds or so lay out the driving, fascinating ‘what the hell is this thing’ mystery lined with all manner of juicy body horror and drama—yet the core high-concept premise is laid out almost immediately, you know what's at stake. The last third… escalates.

It’s full of the usual meaty Seth themes, iterating on the ideas first laid out in Baru. But it’s a distinct flavour of its own. That escalation is… well, I can’t describe in detail, not while the book isn’t even out, but it’s nuts. Not just for the scale, but for how convincingly it sells concepts that if I described them straightforwardly would sound completely ridiculous.

Equally, it’s a study of a markedly diverse group of characters thrown together from all over the world, each constructed with very evident care and nuance. It goes places that so many writers would probably feel ‘damn, that’s probably way too thorny for someone like me to write about’—and yet somehow, it manages to handle it gracefully each time. Certainly, you can perhaps inevitably tell when Seth is writing from direct experience and when they are (as they used to say back in the ’10s) Writing The Other, if only through what they assume you know and what they need to explain as much as everything—and yet there are always all these telling details (the scientist cursing out R) that make these characters come alive with convincing presence and humour.

(Of course the autistic-ass lesbians are my faves. It’s not as overtly a Lesbian Book as Baru was, but there’s a strong current of gay shit.)

A few other reviewers mention Crichton, but I haven’t read Crichton, so… I’ll have to make other comparisons. But then the thing is it’s very self-aware about existing in the fabric of science fiction. This book is set in our world, not in the near future but the recent past, in the late Obama administration. A lot of the things you might compare it to (including a couple I’ve mentioned, Arrival, Crichton) will be invoked as explicit, in-character allusions as these very sharp, funny, modern people try to make sense of their crazy situation. Sometimes it feels like Tamsyn’s use of memes as texture, but it never gets overbearing. The rhythms of Seth’s prose have been refined by Baru into a powerful suite of devices to make you cackle and go, noooo, Seetttthhhhh…

It’s a fascinating blend of hard-ish scifi, with the big ideas carried by surprisingly accurate higher-mathematical technobabble, and what you could probably best call occultism: narrative and ethics and gods and mythology. Seth always tends to deflect when praised for their ability to hop between a dozen different disciplines and pull them together into one unifying story, saying that they’re just good at looking up summaries, or that they had help from the right people. Maybe so, but it works, it passes the smell test, and Seth’s real genius is their remarkable ability to tie all these big grand ideas back into the world of character and emotion.

Since this is an advance review… I gotta be careful how much I say! Usually I assume you’ve read it if you’re going to and dive straight into the spoilers and long quotes, but here I feel like I should take a little care to avoid describing too precisely the exact beats of the story. (Rest assured I will give it the thorough treatment when it comes out in full).

But, I feel like I want to say something a little more substantial. So here’s a description of the mechanism. If all you want to know is whether you should read this book, hopefully I’ve given you plenty of reasons that the answer is god, yes, do it. If you want to know more, read on.

147 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think about the massacre episode of doctor who a lot. Not only is it the rare companion driven story, but I truthfully love the character drama. Doctor who was originally billed as an educational program for children. The time travel so children could learn about historical events and the future stuff so they could learn about science. And what the massacre does is makes Steven an audience surrogate because he doesn’t know about this tragedy at all.

Doctor Who is a British tv show and this event was a French tragedy, so they might not even be aware this happened. Granted I’m coming at this from an American perspective and like it might’ve been mentioned in a AP European history course I took in high school but not in depth. Just another tragedy of the Protestant reformation.

But here in Doctor who, you learn what happened through Steven’s interactions with those who were there. And as it all plays out you’re forced to contend with the fact that this happened. This was real. They were real people, not just a page in the history. Steven’s reaction of shock and anger to the Doctor asserting that he was right to do as he did and that he wasn’t guilty of Ann’s possible death is how we’d all react. How could he turn that girl away! He saved Katarina from the fall of Troy after all!

But then you’d remember how that played out. What happened to Katarina. And suddenly the Doctor’s motives for leaving Ann behind become more muddled. Was it actually to preserve history? Or was it because he thought Ann had a better chance of surviving the St Bartholomew day’s massacre than she did in the TARDIS?

But Steven doesn’t think of this, and most of the audience probably doesn’t either. So he storms off. Not even caring where the TARDIS lands next. Granted Steven comes back like 5 minutes later and we don’t know why, and the Doctor is absolved of Ann’s murder via Dodo’s existence, but still.

I know I went off topic there at the end but the point is doctor who expertly educated it’s audience on a historical event. And it gets the audience invested in what happened by leveraging their lack of knowledge. So that like Steven, you never want anyone to needlessly die like that again.

It’s probably my favorite who story after remembrance of the daleks and I wish people would give it a chance, despite it being lost. The audio drama version on audible is very well done.

Edit: last thing. A subtle detail I really like is when the Doctor realized what’s about to happen, he called Ann by her name before he told her to leave asap. The first Doctor always called the young women he met my child, so the gravity of what was going to happen hit him hard and they were hiding in a somewhat famous Huguenot’s house. The Doctor was genuinely trying to save her within the rules he thought he had to go by.

#doctor who#classic who#steven taylor#1st doctor#first doctor#the massacre#the massacre of st. Bartholomew day’s eve

103 notes

·

View notes

Note

Oh I’m very very interested in your nonfiction book recs 👀

EDIT: ykw I'm gonna make this a little more organized

I listed a bunch in this post (the last question) but lemme see if I have any additions because I know I was kinda trying to keep it short when I wrote that. (But that being said, that post is the Top Faves Of All Time, so go for those first.)

Freaky medical shit I also liked:

The Fever: How Malaria Has Ruled Humankind for 500,000 Years by Sonia Shah

The Barbary Plague: The Black Death in Victorian San Francisco by Marilyn Chase (I just read this a few weeks ago and OOUUUGGHHHHHH IT'S LITERALLY JUST. LIKE THE RESPONSE TO COVID.)

The Ghost Map: The Story of London's Most Terrifying Epidemic—and How It Changed Science, Cities, and the Modern World by Steven Johnson

Political shit I also liked:

Disability Visibility: First-Person Stories from the Twenty-First Century edited by Alice Wong

The Viral Underclass: The Human Toll When Inequality and Disease Collide by Steven W. Thrasher

Immigrants, Evangelicals, and Politics in an Era of Demographic Change by Janelle S. Wong

History I also liked:

Triangle: The Fire That Changed America by David Von Drehle

The Hamlet Fire: A Tragic Story of Cheap Food, Cheap Government, and Cheap Lives by Bryant Simon (between those two you can tell I was on a bit of a "workplace tragedies caused by lax regulations and bad management" kick)

The Radium Girls: The Dark Story of America's Shining Women by Kate Moore (I think everyone knows about this book, including it for completeness)

Promised the Moon: The Untold Story Of The First Women In The Space Race by Stephanie Nolen

The Women's House of Detention: A Queer History of a Forgotten Prison by Hugh Ryan

Butts: A Backstory by Heather Radke (this is nowhere near as fun and cute as you'd assume from the title)

Memoirs I also liked:

The Less People Know About Us: A Mystery of Betrayal, Family Secrets, and Stolen Identity by Axton Betz-Hamilton (I read this before I really got into nonfiction and it was WILD, I tell people about it all the time)

The Best We Could Do by Thi Bui (this one is a graphic not-novel-I-guess-memoir)

Know My Name by Chanel Miller

Other:

Playing Dead: A Journey Through the World of Death Fraud by Elizabeth Greenwood

A False Report: A True Story of Rape in America by Ken Armstrong, T. Christian Miller

Lost Feast: Culinary Extinction and the Future of Food by Lenore Newman

It Came from the Closet: Queer Reflections on Horror by Joe Vallese

AND here are a few on my TBR that I'm really excited for! I decided not to categorize them because they're almost all history:

Silk and Potatoes: Contemporary Arthurian Fantasy by Adam Roberts

Refusing Compulsory Sexuality: A Black Asexual Lens on Our Sex-Obsessed Culture by Sherronda J. Brown

All the Young Men by Ruth Coker Burks

The Kidnapping of Edgardo Mortara by David I. Kertzer (I am actually partway through this right now but in a bit of a dry/confusing section)

The Broadcast 41: Women and the Anti-Communist Blacklist by Carol A. Stabile

The Golden Thread: How Fabric Changed History by Kassia St Clair

A Woman of No Importance: The Untold Story of the American Spy Who Helped Win World War II by Sonia Purnell (have just barely started this)

Time to Dance, a Time to Die: The Extraordinary Story of the Dancing Plague of 1518 by John Waller

The Memoirs of Lady Hyegyŏng: The Autobiographical Writings of a Crown Princess of Eighteenth-Century Korea by Lady Hyegyeong

Miss Major Speaks: The Life and Times of a Black Trans Revolutionary by Miss Major Griffin-Gracy

Too Hot to Touch: The Problem of High-Level Nuclear Waste by William M. Alley, Rosemarie Alley (I'm in the middle of this but it's surprisingly, um. not exciting.)

Going Postal: Rage, Murder, and Rebellion: From Reagan's Workplaces to Clinton's Columbine and Beyond by Mark Ames

Pressure Cooker: Why Home Cooking Won't Solve Our Problems and What We Can Do About It by Joslyn Brenton, Sinikka Elliott, Sarah Bowen

Mountains Beyond Mountains by Tracy Kidder

The Fabric of Civilization: How Textiles Made the World by Virginia Postrel

Women's Work: The First 20,000 Years Women, Cloth, and Society in Early Times by Elizabeth Wayland Barber

Medieval Gentlewoman: Life in a Gentry Household in the Later Middle Ages by Ffiona Swabey

Hitler's First Victims: The Beginning of the Holocaust and One Man's Fight to End It by Timothy W. Ryback

I am soso normal and have very normal interests that are not at all grim :)

131 notes

·

View notes

Note

As a big superhero guy, I have a question: Why do you think it's so common to show Reed Richards, Tony Stark, Hank Pym, Hank McCoy (ESPESCIALLY those last two) as, at best, morally ambiguous and at worst, downright awful in modern portrayals? Is it standard American anti-intellectualism, tied into our growing distrust of science and technology, or is it just that they seem kinda bland?

I don't think it's anti-intellectualism per se. For three of the four I think it's just a consequence of contemporary writers being Allowed To Notice And Unpack Things.

For Reed Richards, it's the result of fans and writers applying a level of scrutiny to early plots and character beats that weren't intended to stand up to any real level of scrutiny. He's a guy who got all his best friends horribly mutated by taking them up in an untested spacecraft. He's a guy who brainwashed a bunch of captured skrulls into thinking they were cows. He's a guy who keeps whipping up extremely specific technological solutions to the problem at hand, which never seem to trickle down to the consumer market- hence the "Reed Richards is Useless" trope. And he's gotta dodge and weave around patriarchal accusations vis a vis a lot of the casual sexism of early FF, where Sue had limited combat utility and was often in the mix as the Damsel-in-distress classic. And obviously excising the unconsidered sexism from the dynamic is the right way to go, but treating that early recklessness/ruthlessness/callousness seriously, as an actual personality flaw that he has, and has to work around, is significantly more interesting than just rewriting the character to not behave like that.

For Iron Man it's the result of people starting to take more seriously the moral implications of the fact that he's an arms dealer and a billionaire. (Apocryphally, Stan Lee did this to see if he could create a character who would be popular with his left-leaning audience despite being everything they hate ideologically, but I take this with a grain of salt.) Another element, I think, is that in preparation for the release of Iron Man, Marvel made him a headliner in Civil War in 2007; the nature of Civil War lent itself to him doing a lot of authoritarian bullshit, and said bullshit sort of set the bar for his capacity for extreme behavior when pressed. Put Iron Man in any situation, try to determine the extent he'll go to in order to resolve it, and you have to take into account that time he was sticking his colleagues in virtual-reality prisons on behalf of the government. A demonstrated willingness to do atrocities for what you think of as the greater good does add some flavor and tension, I have to give them that!

For Hank Pym, it's totally down to the midlife crisis arc from 1981, where he rebranded as Yellowjacket, got drummed out of the Avengers for using excessive force, and battered his wife Janet when she tried to. You know. Talk him out of building a robot to perform a false flag attack against the rest of the team to get back in their good graces. The whole arc was supposed to be a very deliberate tragedy about his mental breakdown but it kind of poisoned the well on the character and became the thing future writers endlessly relitigate, either doubling down on it (The Ultimates, Marvel Zombies) or trying to repudiate it (Mighty Avengers, Avengers Academy.) Even before that, though, he had a pointed loose-cannon mad scientist situation going on even in comparison to the others on this list- his debut was a Twighlight zone-style horror story where he nearly gets himself killed testing the shrinking formula, and he also created Ultron and nearly got everyone killed that way!

I have no idea what's going on with Hank McCoy. I don't think I want to know what's going on with Hank McCoy. Every time I turn my ear in the direction of that corner of the fandom these days, all I hear is screaming. Are you guys alright

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

With April showers, Letters from Watson brings us the first installment of The Sign of the Four, a prospect that makes me quake. When I was a tot of eight years, reading the library's copy of The Boy's Sherlock Holmes with a creeping sense of guilt because I was not at that time (and have not been at any time before or since) a boy, I found The Sign of the Four... long. Very long. I was obviously too young for the concepts, even though I could make sense of the words. (That sums up a lot of my reading in that era.)

I'm also reeling from last week's "The Man with the Watches," an utter tragedy of "be gay, do crime."

What's striking me this time -- what with the introduction of Holmes' cocaine use and also the watch deduction that raises a wince and a shudder from anyone who remembers that BBC Sherlock happened -- is how Watson is being positioned (and I don't mean "positioned in the path of which bullet," though apparently he got hit by more than one while in India).

Cocaine

Watson is progressive! His objections to cocaine sound so mild to us in the twenty-first century, but in 1890, scientific opinion was just barely starting to turn away from seeing cocaine as a wonder drug. It was used for local anesthesia as well as for general pep. Queen Victoria drank Vin Mariani, a wine fortified with cocaine, and so did the Pope. Coca Cola contained cocaine until 1906. Sigmund Freud was a vocal proponent of cocaine for improving mood and performance, until he botched an operation in the early 1890s while high.

A couple hair-raising reads on this topic are Cocaine: The Victorian Wonder Drug and A Cure for (Anything) that Ails You: Cocaine in Victorian Medicine.

So Holmes' original audience would have seen him as an up-to-date scientist using a socially approved means of moderating his mood. His shooting up a 7% solution of cocaine is about equivalent to a 21st century person taking nutritional supplements that are meant to boost brain power.

After all the "say no to drugs" education in the American school system, that's so hard for me to get my brain around, but there we are. Holmes is doing something no more troubling than pouring a glass of whiskey and much more scientific.

Watson, therefore, can be read either as being right at the edge of shifting scientific opinion or as being a fussbudget.

Tinge it with romanticism

I'm firmly Team Watson when Holmes starts criticizing A Study in Scarlet:

He shook his head sadly. “I glanced over it,” said he. “Honestly, I cannot congratulate you upon it. Detection is, or ought to be, an exact science, and should be treated in the same cold and unemotional manner. You have attempted to tinge it with romanticism, which produces much the same effect as if you worked a love-story or an elopement into the fifth proposition of Euclid.”

The reader is being positioned here to view with contempt the exact features of the work that we probably enjoyed. Poor Watson!

Is it possible that some reviewers commented on the melodrama of the Lucy portions? Yes, and it'd be a valid point. Nonetheless, having experienced a good many math classes, I think the fifth proposition of Euclid might be improved by a rom--

wait.

Doyle, you magnificent bastard.

Flatland: A Romance in Many Dimensions was published in 1884. It wasn't a huge success, but it seems likely Doyle could have known it, and it did, in fact, mention a love story in a discussion of angles. Back when I read it in college (because if you "liked math," someone would inevitably give you a copy of Flatland), I missed the social satire but appreciated the geometry.

Watson is canonically an effective popular writer, and I refuse to denigrate him for that.

The Watch

First, Holmes substantially invents forensic science with his monographs on tobacco and on callouses.

Then we learn that Watson is a second son, which fits with his his training for a profession and choosing the army to help make his way.

Watson was not on great terms with his brother before his brother's death. Holmes doesn't explicitly deduce this, but it's there to be deduced. Holmes knew Watson's father was long dead, which could have come up in any number of casual ways. Holmes had no idea that Watson had a brother, so Watson:

Didn't mention the brother in any context, ever.

Didn't set up any framed daguerreotypes from his childhood nor any modern photos made with the collodion process. Having a posed family photo would have been so completely normal, as would being sent new photos by family members.

Never interrupted his routine to visit his brother while living with Holmes.

Did not attend his brother's funeral (unless it took place while Holmes was away) and did not wear a black armband for mourning in Holmes' presence. Neglecting mourning for a relative would have been a sign of serious estrangement.

Holmes is possessed of some level of tact in not expanding on this topic.

Watson is also nobody's fool: he knows there are ways to fool a mark with apparently miraculous knowledge.

The question in my mind is this: did Watson deliberately distract Holmes from asking what was the subject of the telegram?

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Underwater Urban Legends: Jacques Cousteau's Secret Discovery?

(Carthago vol. 3, “Le Monstre de Djibouti”, by Christophe Bec and Milan Jovanovic, 2013)

When I first got interested in ocean creatures as a little girl in the late 90s, we had several oversized white-covered books about Jacques Cousteau's ocean expeditions around the house that my parents let me page through, even though the text was way too small for me to read. A little later on, I read the Cousteau Society's young readers' magazine Dolphin Log/Cousteau Kids every month at the library, especially the selections from Dominique Serafini's comic book adaptations of the Calypso crew's adventures.

As an adult who's still interested in marine science, I've read several of Cousteau's books, and seen some of his documentaries. In 2019, I even got to hear his grandson Fabien speak at an event at the American Museum of Natural History.

Across film, TV, literature, comics, and even music, the Cousteau family’s underwater adventures are pretty well-documented. But one persistent bit of sea-folklore I've come across in various forms and places is an urban legend that at least one adventure wasn't. Somewhere in the world, these stories say, Captain Cousteau saw (or heard) something underwater that was so shocking that he kept it a secret from the world. (Except, presumably, from whoever is repeating the story.)

Could there be any truth behind this fantastic story? What was this "secret discovery"? And where and when did all of this happen? Like most urban legends, there are a lot of conflicting accounts and not a lot of proof.

I'd love to see a site like Skeptoid do a deep dive (heheh) into this story someday, but since they haven't yet, my research is below the cut.

A Secret Discovery?

It's alleged that after a submarine expedition, undersea explorer Jacques Cousteau said, "The world isn't ready for what's down there." (How Stuff Works)

As a reader and a writer, I have to say, this is an excellent pitch for a story. A world-famous explorer who witnessed all kinds of undersea wonders and environmental tragedies choosing to keep a remarkable discovery a secret for some unknown reason? Wouldn't you read that book? I'd read that book!

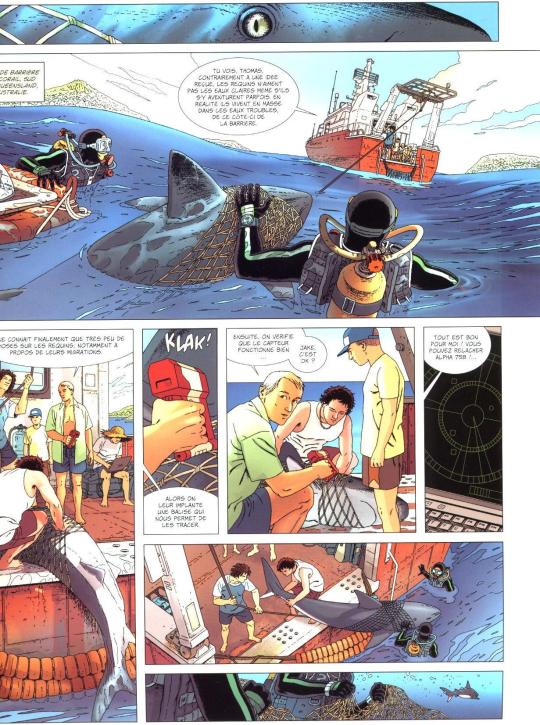

In fact, I did read that book! The French comic Carthago, first published in 2007 and translated into English in 2014, features a character based on Cousteau named Major Bertrand, a famous ocean explorer who made a discovery so shocking that he not only kept it a secret, but retired and lived the rest of his life onshore afterwards. The actual scene shown in flashback is a beat-by-beat retelling of the "Red Sea Monster" version of the story we'll discuss below. According to an interview with the comic's writer Christophe Bec, that scene (and the comic itself) were inspired by an article in the French paranormal magazine Le Monde de l'un découverte (The World of the Unknown) published in February-March 2001. That article is in French here.

Here are the broad outlines of the story as I've seen it in various places online:

Cousteau surfaces, shaken from a dive, OR

The Calypso crew recover either a shark cage that has been destroyed OR

An underwater camera or hydrophone that has recorded something

Cousteau says some variation on "The world is not ready for what I have seen"

Cousteau orders any film or audio recordings of the incident (taken by either divers, underwater equipment, or film crew aboard the ship) to be either destroyed or suppressed and hidden away in a safe

(Some accounts have people saying they actually saw the incident happen on TV, which is unlikely as I don't think any of Cousteau's documentaries were live broadcasts.)

Cousteau is so shaken by what he saw that he never returns to the site of the incident

The Red Sea Monster

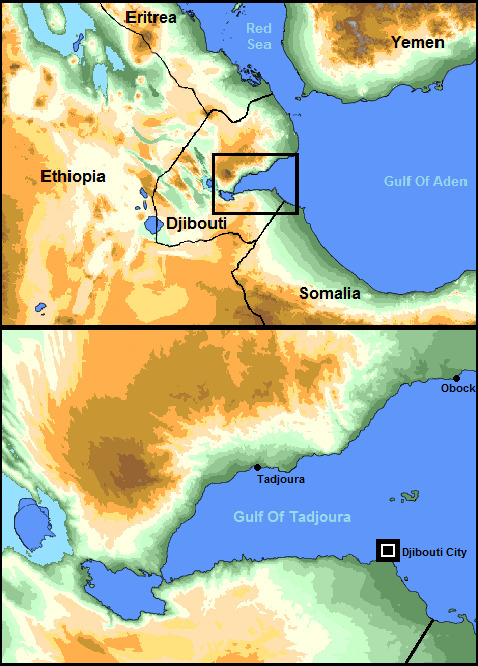

The most famous and detailed version of the story, and the one Carthago adapts, sets the action in the Gulf of Tadjoura off the coast of Djibouti, near where the Red Sea meets the Indian Ocean. Investigating legends of a sea monster in a cove called the Ghoubbet al-Kharab, or Gulf of the Demons, Cousteau's team lowered a camel carcass within a shark cage. When the cage was raised, it had been badly damaged, perhaps even destroyed.

[The Ghoubbet al-Kharab is the little inland bit at left almost cut off from the sea x]

The article in Le Monde de l'un découverte says this incident happened sometime before 26 June 1995, when the secret was revealed by a writer(?) named Stéphane Swirog, and that it had also been discussed on French TV in 1987. (I cannot find any information about a “Stéphane Swirog” online except in reprints of this story, although there is apparently an MMA fighter with that name. Is this one of those hoax articles with backwards names where “Goriws” sound like something hilarious in French that’s lost on me?)

This is a plausible part of the world to set this story, because Cousteau very famously did explore the Red Sea several times! A lot of his film The Silent World was filmed there, and his Conshelf underwater habitat was on the floor of the Red Sea off Sudan. In 2004, Cousteau's son Jean-Michel and grandchildren Fabien and Céline returned to these sites fifty years later for a new documentary you can watch here.

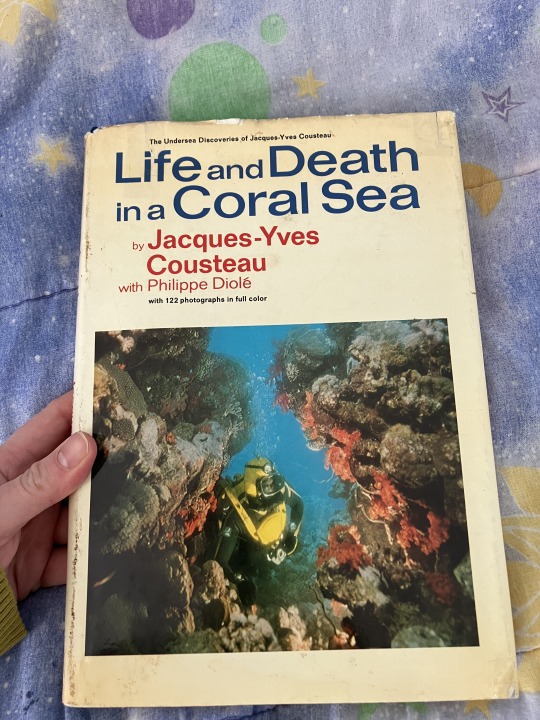

And we know Jacques Cousteau actually DID explore the coast of Djibouti in 1967-68! In his book Life and Death in a Coral Sea (1971), he says that when docked there, his crew, err, heard a strange story...

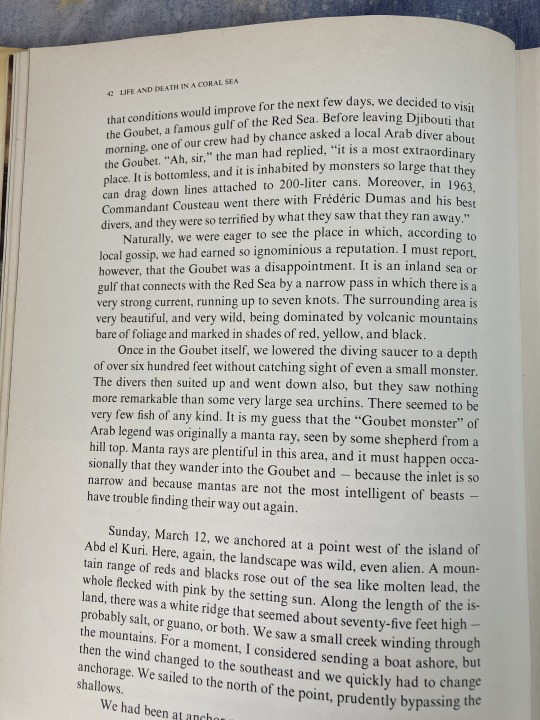

...we decided to visit the Goubet, a famous gulf of the Red Sea. Before leaving Djibouti that morning, one of our crew had by chance asked a local Arab diver about the Goubet. "Ah, sir," the man had replied, "it is a most extraordinary place. It is bottomless, and it is inhabited by monsters so large that they can drag down lines attached to 200-liter cans. Moreover, in 1963, Commandant Cousteau went there with Fredéric Dumas and his best divers, and they were so terrified by what they saw that they ran away."

Naturally, we were eager to see the place in which, according to local gossip, we had earned so ignominious a reputation. I must report, however, that the Goubet was a disappointment. It is an inland sea or gulf that connects with the Red Sea by a narrow pass in which there is a very strong current, running up to seven knots. The surrounding area is very beautiful, and very wild, being dominated by volcanic mountains bare of foliage and marked in shades of red, yellow, and black.

Once in the Goubet itself, we lowered the diving saucer to a depth of over six hundred feet without catching sight of even a small monster. The divers then suited up and went down also, but they saw nothing more remarkable than some very large sea urchins. There seemed to be very few fish of any kind. It is my guess that the "Goubet monster" of Arab legend was originally a manta ray, seen by some shepherd from a hill top. Manta rays are plentiful in this area, and it must happen occasionally that they wander into the Goubet and – because the inlet is so narrow and because mantas are not the most intelligent of beasts – have trouble finding their way out again. (Page 42)

(This is one of those "white-covered books" I still own a copy of!)

That's right, this story is so old it was told TO Cousteau in the late 1960s! It's the only version of the story he seems to have actually heard and commented on, and it was to deny the monster story.

It strikes me that two of the fearsome feats attributed to the Red Sea Monster— pulling air-filled cans/barrels underwater and destroying a shark cage— are things the shark in Jaws also does. While Peter Benchley’s novel came out in 1974, several years later, he did research sharks when writing it, so I wonder if “pulling barrels underwater” was just a bit of shark lore that was going around in the late 60s.

(At least the way it’s shown in the 1975 movie, the MythBusters showed a great white shark is strong enough to briefly pull barrel floats underwater but not to hold them there.)

The more embellished 2001 article post-dates Jaws and may be inspired by the cage-destruction scene in the film.

The Depths of Lake Tahoe

Apparently, years ago, Cousteau went scuba diving in Lake Tahoe. He emerged from the water shaken, but not with cold. He said, “The world is not ready for what I have seen.” (Jennifer Skene, “Rumors and Truth in Lake Tahoe”)

Another common account of the “secret discovery” story says that it didn’t happen at sea at all, but rather in the depths of landlocked Lake Tahoe, on the California-Nevada border. This is the version of the story most commonly associated with the “the world isn’t ready” quote. The Lake Tahoe version usually keeps things vague, speculating that perhaps Cousteau saw local legendary lake monster Tahoe Tessie OR a layer of hundreds of perfectly-preserved bodies of Chinese railroad workers or mafia victims floating eerily in mid-waters, OR some other mysterious thing too horrific to describe.

[Unspeakable horrors such as dinky maps found on Bing]

Both Tessie and the well-preserved bodies are urban legends seen discussed elsewhere without the Cousteau connection. Other legends speculate that the lake hides sharks, mermaids, an underground tunnel to Pyramid Lake, a crashed WWII bomber, and a fortune in gold bullion. Just your ISO standard set of underwater legends, really.

However, unlike the Red Sea, there is no evidence that Jacques Cousteau ever visited Lake Tahoe, let alone dove there!

According to other explorers who have explored the lake’s depths, the cold, clear waters do provide eerie visibility to the shipwrecks and sunken trees found there. While people have died in and around the lake and bodies are sometimes found, the more sensational claims of uncanny preservation and bodies eerily floating in mid-water, never rising or sinking, do not fit with Lake Tahoe’s known physical conditions.

The Screams of Hell

Indeed, the French diver Jacques Cousteau was swimming over Cuba some years ago, and he heard screaming noises at the bottom of the ocean. ... And Jacques Cousteau was so shaken up by what he had heard in the seas off Cuba, he never swam there again. ... He heard what he believed to be screaming, shouting, people being tortured, just as the Bible teaches. ("Ex-Catholics for Christ")

Yet another version of the story says that Cousteau heard the sounds of agonized screaming underwater, either while diving himself or recorded on a hydrophone, and possibly considered them the screams of souls in hell. These versions of the story tend to be vaguer, not always naming a time or place when this happened. (That version put it in Cuba, another in Greece, others vaguely “somewhere in the Bermuda Triangle”.)

That's probably because this version is just an adaptation of another, more well-known urban legend about Soviet geologists digging into hell and recording screams that has been repeated in various places since the 1980s. (You can see some of the problems with that story at the site linked.)

(Cousteau did explore Cuba’s waters in the mid-1980s as seen in the documentary, Cuba: Waters of Destiny. You won’t hear any screams from Hell in that documentary, but there is a guest appearance from Fidel Castro!)

Another religion-related urban legend about Jacques Cousteau is that he converted to Islam after discovering the Quran was correct about the mixing of the waters of the Red Sea and Indian Ocean. This isn't true, either. In some places I'd seen this repeated in the same context as an equally-untrue claim that Neil Armstrong converted to Islam after hearing the call to prayer on the moon, and misremembered this as a claim Cousteau had heard the call to prayer underwater for a less-disturbing twist on the idea that the secret discovery was something heard underwater rather than seen, but as far as I can tell, that isn't the case.

Bells in Random Order

Do you know Jacques Cousteau?

Well, they said on the radio

That he hears bells in random order

Deep beneath the perfect water

("Perfect Water")

The Blue Öyster Cult song "Perfect Water" has the lyrics above, which may be a reference to the "secret discovery" legend and specifically the above idea that it was a mysterious sound heard underwater. The band is known for having many references to legends, conspiracy theories, and the supernatural in other songs. "Perfect Water" was on the album Club Ninja, released in December 1985, post-dating Life and Death in a Coral Sea but predating the most famous accounts of the “Well to Hell” story. I can't find any other sources talking about Cousteau and mysterious bells.

This website instead thinks the lyrics are referring to Cousteau's actual descriptions of walruses as making sounds similar to bells in his writings and films. You can hear a walrus making a bell sound here.

Ask Me Anything

During an AMA session on Reddit in 2018, Fabien Cousteau (FCNomad) was asked about three different versions of this story (Djibouti, Lake Tahoe, and Fort Peck Reservoir in Montana.) He seemed most familiar with the Lake Tahoe version.

sotpsean: Hello, Mr Cousteau! It's an honour. When I was a child, family lived in Djibouti, Africa,(my father was a French Foreign Legionnaire). There was a local legend about a "sea monster" living in Lac Goubet. I've heard that your Grandfather might have investigated Lac Goubet in search of this "monster". Locals have thought it to be a prehistoric shark cut off from the sea. I've always wondered if someone might be able to shed light on this subject. Have you heard of this? Thanks for doing this AMA!

FCNomad: Great to chat with you. French foreign legion? Serious stuff. There are legends of "sea monsters" in every body of water out there. Until we explore them we will not know for sure ;-) Lets go see!

[x]

-

HulkVomit: Why did your grandfather never want to dive in Ft Peck Reservoir again? Would you ever come dive in it?

Account-002: I am also REALLY curious about this. My Dad thought it was because if the siltyness of the water, combined with a possible encounter with multiple giant catfish/paddlefish that put him off.

FCNomad: That does seem plausible and potentially sound due to the potential risks. He was focussed on filmmaking and if you can't see anything its hard to tell a visual story…

[x]

-

TeddysGhost: Hi there, I live at Lake Tahoe and it is a common story around here that your grandfather went into the lake once and when he emerged he warned people that the world isn't ready to see what's down there? What do.you know about that story? Is there even a shred of legitimacy and if so what did he see?

FCNomad: Ive heard this rumor as well. We were supposed to investigate on a new TV series but we never got the chance…

[x]

Conclusions

...yeah, all versions of this story sound pretty fake to me. Sorry.

As Fabien says, almost every body of water has sea and lake monster legends attached to it, because the world’s waters really are mysterious, unpredictable, and dangerous. But over time, your local legendary water monster can become familiar, almost a sort of community mascot.

When reading the archives of The Liberator, a famous anti-slavery newspaper published in Boston in the mid-1800s, I found several articles where the writers referred to the New England sea serpent in these kinds of familiar terms, since to Bostonians it was a “local” monster. They even called it “our American sea serpent”— the children and grandchildren of the Minutemen, still defining their identity as Americans, could boast that England didn’t have such a cool monster.

In modern times, of course, a local monster legend can also be a major tourist attraction. Most of the sites I found repeating the Djibouti and Lake Tahoe versions of the story were… travel sites for Djibouti and Lake Tahoe (especially diving travel sites).

To present your local monster story as “verified” by a famous underwater explorer like Jacques Cousteau makes it sound authentic. It certainly spices things up for people planning their vacations, especially divers. And to say that your local monster scared away a globetrotting adventurer like Cousteau who had faced so many other perils all over the world definitely adds to the “local pride” angle. In Djibouti, a French colony that was having a vote in 1967 about whether to become independent, a story about a local monster scaring away a famous Frenchman may have had an appealing nationalist undertone.

The writer for Le Monde de l'un découverte, however, probably just wanted to tell a rip-roaring sea story. The presumably-French writer, writing for a French magazine, would have been writing for an audience who had grown up following Cousteau’s adventures. Perhaps they combed his writings in search of any mention of sea monsters that could fit in their paranormal magazine, found the passage about Djibouti in Life and Death in a Coral Sea, and created a more sensational version that conveniently left out Cousteau’s own debunking. For an audience who had grown up with Cousteau, what could be more exciting than hearing about one more adventure of their late hero, totally new and unseen, and a discovery so shocking it was being kept secret?

And, like I said, it does make for a great story! No wonder it inspired Christophe Bec to write his own version! And with the decades-long tradition of fictional stories parodying and homaging Jacques Cousteau, I can’t blame you if this piece has inspired you to write your own version of the “secret discovery” story— just please, make it clear that your fiction is fiction.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

cast: ateez & txt & enhypen ✗ reader

synopsis: a collection of ateez, txt, and enhypen works based on author's favorite radiohead songs

genre: variative for each member

based on: music radiohead's discography from albums “the bends”, "ok computer", "kid a", "amnesiac", "in rainbows", and "ok computer oknotok 1997 2017" (1995-2017)

status: subterranean homesick alien out now!

message from the moon: do remember that this is fiction and all the actions the idols do in these works do not reflect what they are in the real world. this is a non-priority anthology so all stories are standalone, won't have any schedule for deadlines, and will be written on my availability! also, note that the infos written below aren't the final one so i can add/subtract anything such as each of the synopsis which will have its final form when the certain fic is released

taglist? right here

listen to all 20 tracks!

you're turning into something you are not

cast: frat bro!sunghoon ✗ sorority girl!fem.reader

genre: romantic comedy, greek life au, college au, angst, mature content (smut)

inspired by: literature the prince and the pauper (1881)

it wears me out

cast: san ✗ fem.reader

genre: adventure, sci-fi, romance, dystopian, angst

inspired by: movie wall-e (2008)

you do it to yourself

cast: wooyoung ✗ fem.reader

genre: modern dystopia, thriller, tragedy

inspired by: tv show black mirror (2011-present)

this, this is our new song

cast: idol!hongjoong ✗ indie musician!fem.reader

genre: drama, coming of age, musicians au

i am back to save the universe

cast: jungwon ✗ fem.reader

genre: superhero fiction, adolescence, science fiction, angst

inspired by: comic cloak and dagger

ambition makes you look pretty ugly

cast: hueningkai ✗ reader

genre: content not available, set in the terra incognita universe

inspired by: error 401

they'd think that i'd finally lost it completely

cast: alt kid!soobin ✗ fashion student/designer!fem.reader

synopsis: after soobin's encounter with a person from his original timeline, he experiences doubts if he can settle in this new timeline or not. his alienation and existentialism take a spin in a new world he has to figure out himself, or if he could be courageous enough to ask you to guide him down back to the surface

genre: coming of age, slice of life, romance, drama, friends with benefits au, college/university au, angst, fluff, mature content (drug consumption and explicit smut), set in the time wave universe

this is what you'll get when you mess with us

cast: jay ✗ fem.reader

genre: drama, crime, romance, thriller, angst, mature content (smut)

inspired by: bonnie and clyde but with a dynamic of succession's tom wambsgans and siobhan roy

you know we're friends 'til we die

cast: seonghwa ✗ fem.reader

genre: content not available, set in the terra incognita universe

inspired by: error 404

we are standing on the edge

cast: detective!jongho ✗ detective!fem.reader

genre: crime, mystery, psychological thriller, noir

inspired by: movie se7en (1995)

the worms will come for you, big boots

cast: spy!yeonjun ✗ investigative journalist!fem.reader

genre: action, adventure, drama, agent au, angst

inspired by: movies from the 007 series: the spy who loved me (1977) and tomorrow never dies (1997)

i'm not here, this isn't happening

cast: singer-songwriter!taehyun ✗ up-and-coming actress!fem.reader

genre: drama, childhood friends au, fame au, angst, mature content (suicidal thoughts, manipulation, exploitation), set in early 2000s

help me get back to your arms

cast: movie character!heeseung ✗ fan!gn.reader

genre: psychological thriller, parasocial relationship, angst

there was nothing to fear and nothing to doubt

cast: yeosang ✗ reader

genre: adventure, action, mystery

inspired by: video game silent hill 2 (2001)

catch the mouse

cast: beomgyu ✗ fem.reader

genre: adventure, drama, thriller, road trip au, run away au, angst, mature content (smut)

inspired by: movies bones and all (2022), american honey (2016), and y tu mamá también (2001)

one by one

cast: guitarist!mingi ✗ session musician!fem.reader

genre: rock band au, angst

inspired by: documentary meeting people is easy (1998)

it is the 21st century

cast: niki ✗ fem.reader

genre: enemies to lovers?, high school au, angst, fluff

inspired by: folk story mulan

because we separate like ripples on a blank shore

cast: guardian angel!sunoo ✗ human!gn.reader

genre: fantasy, angel au, angst

inspired by: the boyz's roar concept (2023)

i don't want to be your friend, i just want to be your lover

cast: yunho ✗ reader

genre: drama, toxic relationship, friends to lovers au, angst, mature content (smut)

the beat goes round and round

cast: jake ✗ fem.reader

genre: time-loop, science fiction, mystery, drama, fantasy, romance, gang au

inspired by: movie groundhog day (1993) meets musical west side story

NOTABLE MENTIONS (written fics and the radiohead songs in their playlists)

let down ; exit music (for a film) - time wave

weird fishes/arpeggi - troubled pixies

all i need ; go slowly ; spectre - isobel

© writingmochi on tumblr, 2021-2024. all rights reserved

#k-labels#ateez imagines#txt imagines#enhypen imagines#ateez scenarios#txt scenarios#enhypen scenarios#ateez x reader#txt x reader#enhypen x reader#rsc: fm#cs: ateez#cs: txt#cs: enhypen#sc: regina

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

One of the great tragedies of the Rust Belt* is that it did not define itself as a distinct cultural region until well after its great era of flourishing was over. For the century from about 1850-1950, this area was not merely the industrial heart of the nation, but also its cultural center. And yet the inhabitants of the area, if they thought of themselves as having a regional identity at all, it was as inhabitants of the generic ‘north’. Its status as a center of cultural innovation was pooh-poohed by the fact that the nation’s political and intellectual elite was, even as it is today, strongly based to the coastal northeast, and this Eurocentric elite had a very different set of priorities than the cultural avant-garde of the as-yet-unRusted-Belt. This area produced little in the way of ‘high art’ in the expected form of novels, symphonies, and oil paintings. But what it did produce...

In 1900, Chicago was the occult capital of the nation, a hotbed of wild theorizing and underground publishing of all manner of Theosophical weirdness. Meanwhile, Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright were producing the first wholly indigenous tradition of monumental architecture, setting a pattern for all of urban modernity. The Dayton, Ohio based Wright brothers - often abused in pop-historiography as some sort of rude mechanicals - were slowly and methodically systematizing the science of aerodynamics in preparation for the first ever instance of heaver-than-air flight in human history, with world-shaking consequences. And up in Detroit, Henry Ford was not merely revolutionizing transportation and manufacturing, but setting a standard for industrial relations that would create an unbelievably influential model for decades to come. It might sound strange to modern ears to cite Henry Ford as a bleeding-edge figure, but Fordism served as an inspiration to both Bolsheviks and Fascists, as well as to domestic New Dealers, while simultaneously pleasing and alarming old-fashioned Anglo liberals. The Long 20th Century is a series of footnotes to the Rust Belt Golden Age.

As can be seen from this too-brief summary of the luminaries of the epoch, it was a deeply unique Golden Age, characterized by cultural traits all its own. Technical prowess, utopian visions, and thorough systematization were its characteristics, as was a sense that a lone individual or small group could, through sheer innovative genius, change the world. While the archetype of the Mad Scientist is based on Mitteleuropean models, it was here in Mittelamerika that it achieved its apotheosis. The definitive cultural history of this region and era has yet to be written**, which just shows how underappreciated the underlying unity still is, but it in a large part contributed to the dynamic optimism that we all now take for granted as distinctively ‘American.’ But as the area felt the collapse of the long bubble economy that funded its flourishing, and its brightest sons and daughters fled west to contribute to the explosion of creativity along the Pacific slope that is now likewise collapsing, it finally awakened to a sense of unity that had previously been hidden by arbitrary State boundaries.

That, at some point, this area will again be the center of some sort of vigorous culture seems an inevitability of human geography, but will it again share the same features of optimism and technical prowess, or were those mere incidental features of a bunch of people with a Protestant work ethic suddenly getting access to the tremendous wealth provided by a vast agricultural base + fossil fuels? Man alive, I don’t have the slightest clue, but I hope that there is some sort of afterlife or metempsychosis so I can find out.