#US National Adviser threatens to Beijing

Text

Saudi Arabia dives into Ukraine war peace push with Jeddah talks

India has also confirmed its attendance in Jeddah, describing the move as in line "with our longstanding position" that "dialogue and diplomacy is the way forward."

RIYADH: Saudi Arabia was set to host talks on the Ukraine war on Saturday in the latest flexing of its diplomatic muscle, though expectations are mild for what the gathering might achieve.

The meeting of national security advisers and other officials in the Red Sea coastal city of Jeddah underscores Riyadh's "readiness to exert its good offices to contribute to reaching a solution that will result in permanent peace," the official Saudi Press Agency said Friday.

Invitations were sent to around 30 countries, Russia not among them, according to diplomats familiar with the preparations. The SPA report said only that "a number of countries" would attend.

It follows Ukraine-organised talks in Copenhagen in June that were designed to be informal and did not yield an official statement.

Instead, diplomats said the sessions were intended to engage a range of countries in debates about a path towards peace, notably members of the BRICS bloc with Russia that have adopted a more neutral stance on the war in contrast to Western powers.

Speaking on Friday, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky welcomed the wide range of countries represented in the Jeddah talks, including developing countries that have been hit hard by the surge in food prices triggered by the war.

"This is very important because, on issues such as food security, the fate of millions of people in Africa, Asia, and other parts of the world directly depends on how fast the world moves to implement the peace formula," he said.

Saudi Arabia, the world's biggest crude exporter which works closely with Russia on oil policy, has touted its ties to both sides and positioned itself as a possible mediator in the war, now nearly a year and a half old.

"In hosting the summit, Saudi Arabia wants to reinforce its bid to become a global middle power with the ability to mediate conflicts while asking us to forget some of its failed strategies and actions of the past, like its Yemen intervention or the murder of Jamal Khashoggi," said Joost Hiltermann, Middle East programme director for the International Crisis Group.

The 2018 slaying of Khashoggi, a Saudi columnist for The Washington Post, by Saudi agents in Turkey once threatened to isolate Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, the kingdom's de facto ruler. But the energy crisis produced by the Ukraine war elevated Saudi Arabia's global importance, helping to facilitate his rehabilitation.

Moving forward Riyadh "wants to be in the company of an India or a Brazil, because only as a club can these middle powers hope to have an impact on the world stage," Hiltermann added.

"Whether they will be able to agree on all things, such as the Ukraine war, is a big question."

'Balancing'

Russia invaded Ukraine on February 24, 2022, failing in its attempt to take Kyiv but seizing swathes of territory that Western-backed Ukrainian troops are fighting to recapture.

Beijing, which says it is a neutral party in the conflict but has been criticised by Western capitals for refusing to condemn Moscow, announced on Friday it would participate in the Jeddah talks. "China is willing to work with the international community to continue to play a constructive role in promoting a political settlement of the Ukraine crisis," said foreign ministry spokesperson Wang Wenbin.

India has also confirmed its attendance in Jeddah, describing the move as in line "with our longstanding position" that "dialogue and diplomacy is the way forward."

South Africa said it too will take part.

Saudi Arabia has backed UN Security Council resolutions denouncing Russia's invasion as well as its unilateral annexation of territory in eastern Ukraine.

Yet last year, Washington criticised oil production cuts approved in October, saying they amounted to "aligning with Russia" in the war.

This May, the kingdom hosted Zelensky at an Arab summit in Jeddah, where he accused some Arab leaders of turning "a blind eye" to the horrors of Russia's invasion.

In sum, Riyadh has adopted a "classic balancing strategy" that could soften Russia's response to this weekend's summit, said Umar Karim, an expert on Saudi politics at the University of Birmingham.

"They're working with the Russians on several files, so I guess Russia will deem such an initiative if not totally favourable then not unacceptable as well."

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

https://libertarianinstitute.org/news-roundup/news-roundup-9-18-2023/

Here is your daily roundup of today's news:

News Roundup 9/18/2023

by Kyle Anzalone

US News

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky is expected to visit Washington next week as Congress debates the $24 billion in additional spending on the proxy war in Ukraine that the White House has requested. AWC

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky implied in an interview with The Economist that Ukrainian refugees in Europe might resort to terrorism if Western aid to Ukraine is curtailed. AWC

Senator Jack Reed is leading an aggressive probe into Elon Musk and SpaceX’s role in the American war industry. AWC

Sweden said Thursday that Ukrainian pilots have completed a first round of training on Swedish-made Gripen fighter jets. AWC

The US State Department and Treasury announced on Thursday a large sanctions package targeting Moscow’s trade with some of Washington’s allies and partners. The aim of this new sanctions package, one of the largest yet, is to block off Russia’s access to money, financial channels and Western technology allegedly being used to bolster the Kremlin’s war effort. The Institute

As Kiev’s offensive fails to achieve its goals, Western officials are increasingly preparing for a war of attrition in Ukraine. Prague says it is searching its military stockpiles for more weapons to send to Ukraine. The Institute

Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov blasted the US for waging a proxy war in Ukraine. The Washington-led North Atlantic alliance has transferred nearly $100 billion in military aid to Kyiv. Lavrov said the White House was controlling Ukraine’s military decisions. AWC

North Korean Supreme Leader Kim Jong Un concluded his six-day state visit to Russia on Sunday. While Kim did not ink an official agreement with Russian President Vladimir Putin, the two leaders discussed several domains where the two nations planned to increase cooperation. The growing ties between Moscow and Pyongyang come as President Joe Biden has pledged to isolate Russia from the rest of the world. AWC

The top-ranking American military official and the civilian head of the North Atlantic alliance believe the war in Ukraine will continue for years if Kyiv is to achieve its military goals. Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky has signed a decree outlawing talks with Russia and plans to restore Ukraine’s pre-2014 borders. AWC

Senator Jack Reed is leading an aggressive probe into Elon Musk and SpaceX’s role in the American war industry. The investigation stems from an incident where SpaceX declined a request from the Ukrainian government to extend the range of Starlink for an attack on Russia. That incident has been widely misreported as Musk ordering SpaceX to deactivate Starlink to thwart the Ukrainian attack. AWC

China

The US will withhold $85 million in annual military aid to Egypt and redirect some of the funds to Taiwan, The Wall Street Journal reported on Wednesday. AWC

China has been conducting major military drills near Taiwan and other areas of the western Pacific in an effort to push back against the increasing US activity in the region. AWC

In February, a Chinese balloon floated over the US, prompting politicians on both sides of the aisle to claim Beijing was threatening Americans. The event led American officials to cancel high-level meetings with their Chinese diplomats. Seven months later, Gen. Mark Milley said the balloon never collected intelligence. AWC

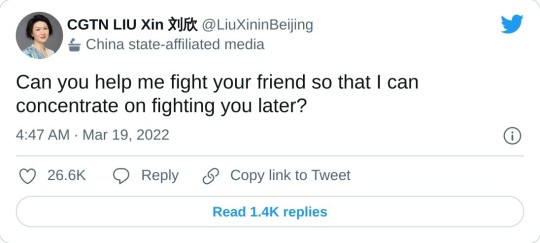

National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan held 12 hours of meetings with Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi in Malta this weekend, potentially paving the way for leader-level discussions later this year. Although the talks come as tensions are soaring between the world’s two largest economies, the meeting has been described as “candid, substantive and constructive,” according to separate statements published Sunday by the White House and the Chinese Foreign Ministry. AWC

Iran

The US issued dozens of sanctions on Iran as Washington and Tehran negotiate a deal that could see several prisoners released. Additionally, France, Germany, and the UK extended sanctions on Iran that were set to expire. AWC

Niger

The commander of US Air Forces in Europe and Africa told reporters Wednesday that the US is considering moving its drone base in Niger following the July 26 coup that ousted President Mohamed Bazoum. AWC

Niger, Mali, and Burkina Faso have signed a charter establishing a mutual defense pact, dubbed the Alliance of Sahel States, on Saturday. The pact commits the three sides to support one another, including with military forces, in response to any external aggression or armed rebellion. It has been described as a “collective [defense] and mutual assistance framework” by Mali military leader Assimi Goita. AWC

Read More

0 notes

Text

Former National Security Adviser, War Criminal and Boak Bollocks John Bolton after speaking in a panel hosted by the National Council of Resistance of Iran – U.S. Representative Office on August 17, 2022 in Washington, DC. © Getty Images / Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images

Ukraine ‘Most Threatened’ by China – Criminal War Hawk Boak Bollocks Bolton

The former US national security adviser says he expects Beijing to side with Moscow on key issues

— 25 February 2023 | RT

Former Top US War Hawk Diplomat War Criminal John Bolton says he doubts that China can legitimately hold a position of neutrality in the Russia-Ukraine conflict, even as Beijing called for a ceasefire and the resumption of peace talks one year after the launch of Moscow’s military operation in Ukraine.

Bolton, who has garnered a reputation for hawkish, interventionist foreign policy stances throughout his political career, has been a prominent critic of China’s policies as it relates to an independent Taiwan and the alleged state-sanctioned theft of Western intellectual property. On Friday, he fired another salvo towards Beijing and the nature of its relationship with Russia.

“A lot of so-called experts have said that China was dismayed by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine,” Bolton told the Washington Post. “I think we’ve seen in recent days proof positive that’s not true.”

Bolton added that China had upped its imports of gas and oil from Russian providers to make up for the impact of Western sanctions, and suggested that China’s roadmap to peace in Ukraine would likely have been, he said, signed-off by Moscow.

“So, to be clear, I think China’s in this with both feet on Russia’s side,” he said. “And while I certainly don’t diminish the threat that China poses to Taiwan and countries in East and South Asia, I would say the most threatened country in the world today from China is Ukraine.”

Bolton, who was a key adviser in the Donald Trump administration for a 17-month spell between April 2018 and September 2019, added that he believes “the Russians and the Chinese are in this together,” referring to the conflict in Ukraine as a “global war.”

“The Chinese have, from the beginning, politically, and I think militarily, had Russia’s back,” Bolton explained. “And the concomitant other side of that is that if China, for example, were to try to attack Taiwan, or throw a blockade around it, they would expect Russia to have their back.”

China’s 12-point peace-brokering document, which it issued on Friday, called for an end to hostilities in Ukraine, as well as the removal of Western sanctions on Russia.

However, Beijing’s stance has been criticized in the West as being undermined by the country’s diplomatic and economic support for Russia. Various Western officials have also warned that China may be considering providing arms to Moscow – an assertion which Beijing denies.

0 notes

Text

Republicans Pounce on Balloon Incident

LOS ANGELES (OnlineColumnist.com), Feb. 5, 2023.--Rep. Mike Turner (R-Ohio) pounced on 80-year-old President Joe Biden for his delayed response to shooting down a Chinese spy balloon when it strayed into U.S. air space Tuesday, Jan. 31. Biden finally ordered the Pentagon to shoot down the spy craft Feb. 5 over Myrtle Beach, South Caroline, about six miles off the coast. “The president taking it down over the Atlantic is sort of tackling the quarterback after the game is over,” Turner told NBC’s “Meet the Press.” “This should never have been allowed to enter the United States and it never should have allowed to complete its mission,” Turner said, making more out of the national security significance, assuming the intel-gathering balloon collected valuable data on U.S. nuclear arsenals in Montana and over the Midwest. Whether China got any actionable intel is anyone’s guess. Most experts don’t think the spy craft produced anything significant.

Turner hopes to make political hay at a time that Biden’s approval ratings have shown a moderate bounce after a favorable unemployment rates showing the lowest unemployment rate in 55 years. Republicans look far from retaking the White House with only 76-year-old former President Donald Trump, possibly former South Carolina Gov. Nikki Haley, announcing for president. Surviving Koch brother Charles Koch signals he has no plans of supporting Trump’s third run for president. While that’s nothing new, since Koch Industries did not support Trump in 2016, it does signal an active anti-Trump movement in the Republican Party. Former House Speaker Paul Ryan (R-Wis.) signaled he’ll do everything possible to find an alternative candidate to keep Trump from the GOP nomination. Turner, who heads the House Intelligence Committee, slammed Biden for a slow response.

Biden has serious problems with Communist China, all part of his own doing, starting off with 60-year-old Secretary of State Antony Blinken and 45-year-old National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan alienating Beijing. Blinken and Sullivan accused Beijing March 18, 2021 at an Anchorage, Alaska summit of genocide against Muslim Uyghurs in Western China. When it comes to more recent insults, Biden told Chinese President Xi Jinping Sept. 23, 2022 he would send U.S troops to defend Taiwan in the event of a Chinese takeover. Xi accused Biden of violating the 1979 Taiwan Relations Act that forced the U.S. to recognize one China, the one in Beijing. Whatever the tensions with China over Taiwan, shooting down the Chinese spy balloon won’t help bilateral relations. Turner only looks at domestic U.S. politics, not the prospects of war with the Peoples Republic of China.

Biden’s Feb. 4 decision to shoot down the Chinese spy balloon carries certain risks of further deteriorating U.S.-Chinese relations. Biden had to act at some point, claiming the delay was only due to safety from the sizable debris field for U.S. citizens. “Allowing China to do a similar act before an clearly in this one no seeing the urgency of what was unfolding ,” Turner said, criticizing Biden for not informing Congress sooner, especially the Gang of Eight, of Republicans and Democrats. Sen. Cory Booker (D-N.Y.), agreed with Biden’s more cautious approach. “This is an administration that’s been reaching out across the aisle to counter China aggression and espionage but also keep them at the table,” Booker said. Booker knows that U.S.-Chinese relations are at the lowest point in decades, with China threatening to invade Taiwan. Former House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) pushed China to the brink visiting Taipei Aug. 4, 2022.

Booker and other Democrats know the abysmal state of relations with the U.S. and China. Democrats also know that Biden chose to fund a proxy war using Ukrainian troops against the Russian Federation. With one war active in Ukraine against the Kremlin, pushing China into a new war over Taiwan would be catastrophic for U.S. national security. ”To create another standard for Biden when Trump, it seems, allowed this to go over the United States is just a big hypocritical,” Booker said. Democrats and the press like to point out that Trump did nothing when confronted with Chinese surveillance balloons during his time in office. If Chinese spy balloons strayed into U.S. air space on Trump’s watch, it was only for brief moments, not, as Biden did, allowing the spy balloon to cross the entire United States. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin confirmed China’s spying activities.

Austin said that the Chinese surveillance balloon attempted to collect data on U.S. strategic nuclear sites around the country. Austn said “that the surveillance balloon that was brought down above U.S. territorial waters was being used by the Peoples Republic of China in an attempt to surveil strategic sites in the continental U.S.” So, when Turner complains about Biden letting the balloon complete its mission traveling across the U.S., he has a point. How much data was actually collected is anyone’s guess. Most Pentagon analysts think that satellite data provides China with more active intel than anything the balloon collected on its transcontinental flight. Whether delayed or not, Biden did the right thing shooting down the balloon, sending Beijing a message about trespassing on U.S. territory. China continues to deny that its spy craft was anything other than a harmless weather balloon.

About the Author

John M. Curtis writes politically neutral commentary analyzing spin in national and global news. He’s editor of OnlineColumnist.com and author of Dodging The Bullet and Operation Charisma.

1 note

·

View note

Text

With the constant threat of war, Russian President Vladimir Putin has successfully managed to divert the attention of the Biden administration from Asia, which has been the primary focus of global politics lately.

The news of the Sino-US conflict has become secondary immediately, and the Indo-Pacific strategy of America seems to be pushed to the back-end.

The United States is looking to Europe so that its relations with its long-lasting allies from Europe, which had already its terms settled with America.

Russia was largely being ignored by the western world in the aftermath of the Cold War, and it was not even considered a direct threat to the United States.

As America was making its foreign policy decisions related to Chinese ambitions, Russia was becoming irrelevant. However, its aggression against Ukraine has made it relevant in global politics once again.

The core focus of the Biden administration’s foreign policy was to play a “pivotal role” in Asia; however, it is confronted with a challenge it did not anticipate.

This is how the foreign policy of America works. Congress, the White House, and the media can only focus on one bigger foreign policy issue at a time.

This is why the Chinese Olympics and its human rights violations have become a secondary thing for the United States.

Major Events in Asia Ignored by America

As Putin threatened to attack Ukraine, some significant events happened in Asia which did not get any traction in America but could have sparked a major outrage otherwise.

North Korea tested a ballistic missile for the sixth time in January 2022.

China had a warring ambition against Taiwan, as it flew 39 warplanes toward the island, one of the largest groups of aircraft in recent memory.

An American F35 plane crashed in the South China Sea, which has become the latest battleground for the Sino-US rivalry.

To add fuel to the fire, Iran, Russia, and China had a joint military drill in the waters of the Indian Ocean.

All of this failed to grab any attention of the American audience, as Russia was adamant enough to deny the US an opportunity to do it.

Top-level strategic and diplomatic officials have been assigned only one job, i.e., to fend off any tensions between Russia and Ukraine to stop Russia’s possible invasion of its neighbor.

One Issue to Another: America is Crisscrossing Among Global Powers

Before this issue, China had global attention, and America moved promptly to sanction the Asian giant for human rights abuses, even refusing to send the diplomatic staff for the Beijing Olympics.

Just in recent days, CIA director William Burns visited Moscow, Secretary of State Antony Blinken is busy in Europe, the national security adviser, many US ambassadors, and the president himself are busy dialing their phones to ease the tensions.

Just recently, China built a bridge on the disputed border with India, which once again may spark a frenzy of war between the two rivals.

India and China came face to face in 2020 as well and had already fought a full-scale war in the region in 1962. But once again, with all resources directed toward Russia, America has no clue of what is happening in Asia.

Currently, Asian stakeholders are looking toward Biden for various issues. Biden is yet to release his Indo-Pacific economic strategy.

Many Asian countries have no ambassador of the United States at all, which is putting America out of the region completely.

Final Thoughts

Considering the fact that the US has been an active player in the Middle East, recalibrating its approach toward Asia is also a must-do task for the Biden administration.

This is a foreign policy emergency as these issues will otherwise start being neglected once America moves toward the midterm election due to the domestic chaos.

If Biden continues playing into the hands of Putin, it will be a drastic choice as he can defer the matter as much as he can.

0 notes

Text

5G wars: the US plot to make Britain ditch Huawei

GCHQ was confident it could work safely with the Chinese tech firm. An American official thought otherwise — and, in a Cabinet Office meeting, shouted about it for five hours

Donald Trump’s arrival in Washington in 2017 had quickly united the Five Eyes spy network against the misinformation emerging from the White House. The assurances given by US agencies to their counterparts in the UK, Canada, Australia and New Zealand proved that the preservation of intelligence-sharing should be safeguarded from politics.

It was a laudable effort — until the CIA and National Security Agency (NSA) sided with White House officials on matters relating to Huawei, the Chinese tech firm with links to the Chinese Communist Party. Britain was determined to engage with Huawei based on a recommendation made by Ciaran Martin, whose team at GCHQ had made detailed intelligence and technology assessments.

A White House delegation arrived in London in May 2019 on a policy-disruption mission. Their brief was to oppose a British plan that would allow Huawei limited access to help build the country’s next-generation 5G cellular data network.

Within minutes of the delegation’s arrival at the Cabinet Office, Martin and other senior officials, including the deputy national security adviser, Madeleine Alessandri, were effectively shouted at by one of their guests for five hours.

That guest was Matthew Pottinger, a former US Marines intelligence officer parachuted into the White House in early 2017 to become the National Security Council’s director on Asia. He was known for his distrust of China’s authoritarian regime, a sentiment shaped during his previous life as a foreign correspondent for The Wall Street Journal in Beijing, where he had been subjected to surveillance and physically attacked by the authorities.

Pottinger’s influence on US policy towards China was immediate on taking up his role. He was described by Steve Bannon, the former White House chief strategist, as “one of the most significant people in the entire US government”. One year into his role, Pottinger had played a key role in the White House’s decision to impose tariffs on $200 billion of Chinese goods. Trump had already declared that “trade wars are good, and easy to win” when he had decided to punish China over, as he saw it, the American jobs being lost to its cheaper workforce. Beijing retaliated with its own tariffs on US products.

While Pottinger and Martin were both in their mid-forties and equally influential in their respective governments, that was pretty much where the similarities ended.

“We were keen to work with the US to counter [China’s strategic] ambitions,” Martin recalled. “The problem was, on our side, we didn’t think Huawei’s limited involvement in UK 5G was the most important thing in a much wider strategic challenge — whereas the US were only interested in that part of the problem, for reasons we couldn’t fathom.”

A British intelligence official who was at the meeting said: “Pottinger just shouted and was entirely uninterested in the UK’s analysis. The message was, ‘We don’t want you to do this, you have no idea how evil China is’. It was five hours of shouting with a prepared, angry and weirdly non-threatening script. We tried to offer a policy discussion but Pottinger didn’t care. We even said that we didn’t contest the analysis of the Chinese threat and explained our technicalities, but the US officials weren’t interested in that. Pottinger was continuously and repeatedly obnoxious.”

Martin had anticipated a debate with the visitors — if not the shouting. The Trump administration had expressed its disapproval of the British plan after details, which should not have been made public for almost another year, were leaked to The Daily Telegraph two weeks earlier by Theresa May’s then defence secretary, Gavin Williamson. He was sacked , despite repeatedly denying being the leaker. He was among a small but vocal group of Conservative MPs who vehemently opposed any involvement from Huawei in the creation of Britain’s 5G network.

Ten years’ distrust

Washington’s hostility to Huawei could be traced back to 2012, when an investigation by the US House intelligence committee concluded that it was a national security threat, because it was unwilling to “provide sufficient evidence” regarding its “relationships or regulatory interaction with Chinese authorities” in Beijing. The Obama administration banned Huawei and another Chinese firm, ZTE, from bidding for US government contracts. Five years later, the Trump administration warned that China’s 2017 National Intelligence Law, which states that organisations must “support, co-operate with and collaborate in national intelligence work”, could force Huawei to snoop for Beijing on countries in which it was operating.

US intelligence agencies and White House officials had repeatedly lobbied all members of the Five Eyes to ban Huawei on national security grounds. While New Zealand had followed Australia and banned the Chinese telecoms company in November 2018, Canada was still considering its options, and would not announce its intention to ban Huawei until May this year. The US secretary of state, Mike Pompeo — a director of the CIA during the early days of the Trump administration — had declared in a thinly veiled warning to Britain in February 2019 that countries using Huawei equipment were a risk to the US. Staff from his office were also reminding their counterparts in Britain that they were risking their place in the Five Eyes should the UK decide to approve Huawei.

In May 2019 — the same month Pottinger flew to Britain for the meeting at the Cabinet Office — the US president signed an executive order to prohibit Chinese companies, including Huawei, from selling equipment in America because of the “undue risk of sabotage” and “catastrophic effects” on communications systems and infrastructure. The Department of Commerce placed Huawei and 68 of its affiliates on a trade blacklist for “activities contrary to the national security or foreign policy interests of the United States”.

Martin gave Pottinger assurances that Huawei’s work on the 5G network would not compromise the UK’s intelligence-sharing channels with the Five Eyes, government systems or nuclear facilities, because such sensitive areas were linked to computer networks inaccessible to Huawei. Such guarantees were not enough to appease their Americans during — or after — their meeting in London.

Lord Darroch, who served as Britain’s national security adviser before becoming the UK’s ambassador in the US in January 2016, said the US delegation “didn’t really have any compelling technical arguments that undermined the GCHQ case. I remember GCHQ seeming pretty unimpressed. The encounter exposed that the US case was really political, not technical. So GCHQ stuck to their guns, and, initially, so did the prime minister.”

Theresa May, who was prime minister until July 2019, said: “Any decision taken by a politician can by definition be described as a political decision, but this was not a decision based on politics. It was based on the fact that we believed that . . . we had the capability of ensuring that we could protect what needed to be protected.”

The unshakable position on Huawei held by the US officials was particularly insulting to their British colleagues, because GCHQ had spotted a technical threat in the Chinese company’s products two years before the company had been banned by the White House. In fact, GCHQ had created an oversight facility in Banbury, Oxfordshire, to identify any risks associated with Huawei’s products. The only reason for not excluding the Chinese company altogether was because its products were significantly cheaper than those of its competitors, Nokia and Ericsson.

The CIA tried to discredit the UK’s position on Huawei in the eyes of its European allies. Officers from the agency’s Belgium station met their counterparts in the French, German, Italian and Norwegian intelligence services, among others, to express their concerns about the UK’s “misjudgment”. British intelligence officials were outraged by what they described as a “black ops” mission facilitated by the CIA — some even calling it a betrayal of friendship. Yet again, the special relationship between London and Washington had been strained and risked being permanently disrupted.

On July 14, 2019, two months after his team clashed with Pottinger in London, Ciaran Martin travelled to Washington with Britain’s national security adviser, Mark Sedwill, to meet US officials at the White House. Among those present were Pottinger and John Bolton, Trump’s latest national security adviser. Notably missing was Sir Kim Darroch, the ambassador, who had been handling the crisis behind the scenes but had been forced to resign a few days earlier after leaked emails revealed he had described Trump as “incompetent”, “insecure” and “inept” in cables he had sent to London shortly after the president had been elected to office.

During the hour-long meeting, Bolton reassured Martin and Sedwill that he was sympathetic to the UK’s assurances and said he would ask members of his own security council to devise a plan that would help resolve their differences over Huawei. Pottinger seemed largely deferential to Bolton during the meeting, and the aggression he had shown in London had all but disappeared. Perhaps it was because he knew the US had a trick up its sleeve.

The new prime minister, Boris Johnson, had supported Martin’s recommendations on dealing with the Chinese telecommunications giant. In January 2020, he gave Huawei limited approval to build the 5G network, but with more limitations, excluding it from access to military and nuclear sites and national infrastructure. Huawei would be allowed to build only the parts of the network that connected equipment and devices to phone masts.

Britain’s defiance was met with the ultimate checkmate. Trump introduced further sanctions in May 2020 that banned Huawei from using US-made chips in its equipment. As a result, Martin could no longer guarantee the security of Huawei’s products, and two months later, in a remarkable public U-turn, Johnson finally banned Huawei from operating in Britain. His move would delay the country’s 5G rollout by up to three years and cost it at least £2 billion to remove all Huawei 5G equipment from its networks by 2027.

Pompeo welcomed Johnson’s decision, saying: “The UK joins a growing list of countries from around the world that are standing up for their national security by prohibiting the use of untrusted, high-risk vendors.” Pottinger must have also been cheering. Not only had his opposition to Huawei’s role in Britain come to fruition, but by the time it did, Trump had promoted him to deputy national security adviser.

“There was a lot of media speculation and parliamentary interest in whether we would ban Huawei or not,”’ said Darroch. “In my time, GCHQ had led on detailed analysis about the risk from Huawei kit on the communications network and had concluded that, provided it was not at the core of the network, it was OK. This analysis was a central part of the discussion at the national security council and key to the then-agreed outcome that Huawei equipment could be used in certain parts of the network. It was basically driven by the analysis of GCHQ . . . It would be legitimate to do it [drop Huawei] for political reasons, or because it was so important to the Americans, or as an expression of Five Eyes solidarity, or whatever. But it shouldn’t be dressed up as technical.”

Martin stepped down as head of GCHQ’s National Cyber Security Centre in September 2020 to become a professor at Oxford University’s Blavatnik School of Government. He maintains that his confidence in the plan for Huawei to help build the country’s 5G network had always been underpinned by technical assessments, and he had been under no illusions about the potential risks that Huawei posed.

“In reality, anyone can have a go at hacking anything,” he said. “We in the UK, thanks to the US sanctions, are now entirely dependent on Nokia and Ericsson. For sure, we trust their boards of directors. But are we seriously saying that just because they’re not Chinese, they can’t be hacked? By neighbouring Russia, for example? Or China?”

0 notes

Text

5G wars: the US plot to make Britain ditch Huawei

GCHQ was confident it could work safely with the Chinese tech firm. An American official thought otherwise — and, in a Cabinet Office meeting, shouted about it for five hours

Donald Trump’s arrival in Washington in 2017 had quickly united the Five Eyes spy network against the misinformation emerging from the White House. The assurances given by US agencies to their counterparts in the UK, Canada, Australia and New Zealand proved that the preservation of intelligence-sharing should be safeguarded from politics.

It was a laudable effort — until the CIA and National Security Agency (NSA) sided with White House officials on matters relating to Huawei, the Chinese tech firm with links to the Chinese Communist Party. Britain was determined to engage with Huawei based on a recommendation made by Ciaran Martin, whose team at GCHQ had made detailed intelligence and technology assessments.

A White House delegation arrived in London in May 2019 on a policy-disruption mission. Their brief was to oppose a British plan that would allow Huawei limited access to help build the country’s next-generation 5G cellular data network.

Within minutes of the delegation’s arrival at the Cabinet Office, Martin and other senior officials, including the deputy national security adviser, Madeleine Alessandri, were effectively shouted at by one of their guests for five hours.

That guest was Matthew Pottinger, a former US Marines intelligence officer parachuted into the White House in early 2017 to become the National Security Council’s director on Asia. He was known for his distrust of China’s authoritarian regime, a sentiment shaped during his previous life as a foreign correspondent for The Wall Street Journal in Beijing, where he had been subjected to surveillance and physically attacked by the authorities.

Pottinger’s influence on US policy towards China was immediate on taking up his role. He was described by Steve Bannon, the former White House chief strategist, as “one of the most significant people in the entire US government”. One year into his role, Pottinger had played a key role in the White House’s decision to impose tariffs on $200 billion of Chinese goods. Trump had already declared that “trade wars are good, and easy to win” when he had decided to punish China over, as he saw it, the American jobs being lost to its cheaper workforce. Beijing retaliated with its own tariffs on US products.

While Pottinger and Martin were both in their mid-forties and equally influential in their respective governments, that was pretty much where the similarities ended.

“We were keen to work with the US to counter [China’s strategic] ambitions,” Martin recalled. “The problem was, on our side, we didn’t think Huawei’s limited involvement in UK 5G was the most important thing in a much wider strategic challenge — whereas the US were only interested in that part of the problem, for reasons we couldn’t fathom.”

A British intelligence official who was at the meeting said: “Pottinger just shouted and was entirely uninterested in the UK’s analysis. The message was, ‘We don’t want you to do this, you have no idea how evil China is’. It was five hours of shouting with a prepared, angry and weirdly non-threatening script. We tried to offer a policy discussion but Pottinger didn’t care. We even said that we didn’t contest the analysis of the Chinese threat and explained our technicalities, but the US officials weren’t interested in that. Pottinger was continuously and repeatedly obnoxious.”

Martin had anticipated a debate with the visitors — if not the shouting. The Trump administration had expressed its disapproval of the British plan after details, which should not have been made public for almost another year, were leaked to The Daily Telegraph two weeks earlier by Theresa May’s then defence secretary, Gavin Williamson. He was sacked , despite repeatedly denying being the leaker. He was among a small but vocal group of Conservative MPs who vehemently opposed any involvement from Huawei in the creation of Britain’s 5G network.

Ten years’ distrust

Washington’s hostility to Huawei could be traced back to 2012, when an investigation by the US House intelligence committee concluded that it was a national security threat, because it was unwilling to “provide sufficient evidence” regarding its “relationships or regulatory interaction with Chinese authorities” in Beijing. The Obama administration banned Huawei and another Chinese firm, ZTE, from bidding for US government contracts. Five years later, the Trump administration warned that China’s 2017 National Intelligence Law, which states that organisations must “support, co-operate with and collaborate in national intelligence work”, could force Huawei to snoop for Beijing on countries in which it was operating.

US intelligence agencies and White House officials had repeatedly lobbied all members of the Five Eyes to ban Huawei on national security grounds. While New Zealand had followed Australia and banned the Chinese telecoms company in November 2018, Canada was still considering its options, and would not announce its intention to ban Huawei until May this year. The US secretary of state, Mike Pompeo — a director of the CIA during the early days of the Trump administration — had declared in a thinly veiled warning to Britain in February 2019 that countries using Huawei equipment were a risk to the US. Staff from his office were also reminding their counterparts in Britain that they were risking their place in the Five Eyes should the UK decide to approve Huawei.

In May 2019 — the same month Pottinger flew to Britain for the meeting at the Cabinet Office — the US president signed an executive order to prohibit Chinese companies, including Huawei, from selling equipment in America because of the “undue risk of sabotage” and “catastrophic effects” on communications systems and infrastructure. The Department of Commerce placed Huawei and 68 of its affiliates on a trade blacklist for “activities contrary to the national security or foreign policy interests of the United States”.

Martin gave Pottinger assurances that Huawei’s work on the 5G network would not compromise the UK’s intelligence-sharing channels with the Five Eyes, government systems or nuclear facilities, because such sensitive areas were linked to computer networks inaccessible to Huawei. Such guarantees were not enough to appease their Americans during — or after — their meeting in London.

Lord Darroch, who served as Britain’s national security adviser before becoming the UK’s ambassador in the US in January 2016, said the US delegation “didn’t really have any compelling technical arguments that undermined the GCHQ case. I remember GCHQ seeming pretty unimpressed. The encounter exposed that the US case was really political, not technical. So GCHQ stuck to their guns, and, initially, so did the prime minister.”

Theresa May, who was prime minister until July 2019, said: “Any decision taken by a politician can by definition be described as a political decision, but this was not a decision based on politics. It was based on the fact that we believed that . . . we had the capability of ensuring that we could protect what needed to be protected.”

The unshakable position on Huawei held by the US officials was particularly insulting to their British colleagues, because GCHQ had spotted a technical threat in the Chinese company’s products two years before the company had been banned by the White House. In fact, GCHQ had created an oversight facility in Banbury, Oxfordshire, to identify any risks associated with Huawei’s products. The only reason for not excluding the Chinese company altogether was because its products were significantly cheaper than those of its competitors, Nokia and Ericsson.

The CIA tried to discredit the UK’s position on Huawei in the eyes of its European allies. Officers from the agency’s Belgium station met their counterparts in the French, German, Italian and Norwegian intelligence services, among others, to express their concerns about the UK’s “misjudgment”. British intelligence officials were outraged by what they described as a “black ops” mission facilitated by the CIA — some even calling it a betrayal of friendship. Yet again, the special relationship between London and Washington had been strained and risked being permanently disrupted.

On July 14, 2019, two months after his team clashed with Pottinger in London, Ciaran Martin travelled to Washington with Britain’s national security adviser, Mark Sedwill, to meet US officials at the White House. Among those present were Pottinger and John Bolton, Trump’s latest national security adviser. Notably missing was Sir Kim Darroch, the ambassador, who had been handling the crisis behind the scenes but had been forced to resign a few days earlier after leaked emails revealed he had described Trump as “incompetent”, “insecure” and “inept” in cables he had sent to London shortly after the president had been elected to office.

During the hour-long meeting, Bolton reassured Martin and Sedwill that he was sympathetic to the UK’s assurances and said he would ask members of his own security council to devise a plan that would help resolve their differences over Huawei. Pottinger seemed largely deferential to Bolton during the meeting, and the aggression he had shown in London had all but disappeared. Perhaps it was because he knew the US had a trick up its sleeve.

The new prime minister, Boris Johnson, had supported Martin’s recommendations on dealing with the Chinese telecommunications giant. In January 2020, he gave Huawei limited approval to build the 5G network, but with more limitations, excluding it from access to military and nuclear sites and national infrastructure. Huawei would be allowed to build only the parts of the network that connected equipment and devices to phone masts.

Britain’s defiance was met with the ultimate checkmate. Trump introduced further sanctions in May 2020 that banned Huawei from using US-made chips in its equipment. As a result, Martin could no longer guarantee the security of Huawei’s products, and two months later, in a remarkable public U-turn, Johnson finally banned Huawei from operating in Britain. His move would delay the country’s 5G rollout by up to three years and cost it at least £2 billion to remove all Huawei 5G equipment from its networks by 2027.

Pompeo welcomed Johnson’s decision, saying: “The UK joins a growing list of countries from around the world that are standing up for their national security by prohibiting the use of untrusted, high-risk vendors.” Pottinger must have also been cheering. Not only had his opposition to Huawei’s role in Britain come to fruition, but by the time it did, Trump had promoted him to deputy national security adviser.

“There was a lot of media speculation and parliamentary interest in whether we would ban Huawei or not,”’ said Darroch. “In my time, GCHQ had led on detailed analysis about the risk from Huawei kit on the communications network and had concluded that, provided it was not at the core of the network, it was OK. This analysis was a central part of the discussion at the national security council and key to the then-agreed outcome that Huawei equipment could be used in certain parts of the network. It was basically driven by the analysis of GCHQ . . . It would be legitimate to do it [drop Huawei] for political reasons, or because it was so important to the Americans, or as an expression of Five Eyes solidarity, or whatever. But it shouldn’t be dressed up as technical.”

Martin stepped down as head of GCHQ’s National Cyber Security Centre in September 2020 to become a professor at Oxford University’s Blavatnik School of Government. He maintains that his confidence in the plan for Huawei to help build the country’s 5G network had always been underpinned by technical assessments, and he had been under no illusions about the potential risks that Huawei posed.

“In reality, anyone can have a go at hacking anything,” he said. “We in the UK, thanks to the US sanctions, are now entirely dependent on Nokia and Ericsson. For sure, we trust their boards of directors. But are we seriously saying that just because they’re not Chinese, they can’t be hacked? By neighbouring Russia, for example? Or China?”

0 notes

Text

5G wars: the US plot to make Britain ditch Huawei

GCHQ was confident it could work safely with the Chinese tech firm. An American official thought otherwise — and, in a Cabinet Office meeting, shouted about it for five hours

Donald Trump’s arrival in Washington in 2017 had quickly united the Five Eyes spy network against the misinformation emerging from the White House. The assurances given by US agencies to their counterparts in the UK, Canada, Australia and New Zealand proved that the preservation of intelligence-sharing should be safeguarded from politics.

It was a laudable effort — until the CIA and National Security Agency (NSA) sided with White House officials on matters relating to Huawei, the Chinese tech firm with links to the Chinese Communist Party. Britain was determined to engage with Huawei based on a recommendation made by Ciaran Martin, whose team at GCHQ had made detailed intelligence and technology assessments.

A White House delegation arrived in London in May 2019 on a policy-disruption mission. Their brief was to oppose a British plan that would allow Huawei limited access to help build the country’s next-generation 5G cellular data network.

Within minutes of the delegation’s arrival at the Cabinet Office, Martin and other senior officials, including the deputy national security adviser, Madeleine Alessandri, were effectively shouted at by one of their guests for five hours.

That guest was Matthew Pottinger, a former US Marines intelligence officer parachuted into the White House in early 2017 to become the National Security Council’s director on Asia. He was known for his distrust of China’s authoritarian regime, a sentiment shaped during his previous life as a foreign correspondent for The Wall Street Journal in Beijing, where he had been subjected to surveillance and physically attacked by the authorities.

Pottinger’s influence on US policy towards China was immediate on taking up his role. He was described by Steve Bannon, the former White House chief strategist, as “one of the most significant people in the entire US government”. One year into his role, Pottinger had played a key role in the White House’s decision to impose tariffs on $200 billion of Chinese goods. Trump had already declared that “trade wars are good, and easy to win” when he had decided to punish China over, as he saw it, the American jobs being lost to its cheaper workforce. Beijing retaliated with its own tariffs on US products.

While Pottinger and Martin were both in their mid-forties and equally influential in their respective governments, that was pretty much where the similarities ended.

“We were keen to work with the US to counter [China’s strategic] ambitions,” Martin recalled. “The problem was, on our side, we didn’t think Huawei’s limited involvement in UK 5G was the most important thing in a much wider strategic challenge — whereas the US were only interested in that part of the problem, for reasons we couldn’t fathom.”

A British intelligence official who was at the meeting said: “Pottinger just shouted and was entirely uninterested in the UK’s analysis. The message was, ‘We don’t want you to do this, you have no idea how evil China is’. It was five hours of shouting with a prepared, angry and weirdly non-threatening script. We tried to offer a policy discussion but Pottinger didn’t care. We even said that we didn’t contest the analysis of the Chinese threat and explained our technicalities, but the US officials weren’t interested in that. Pottinger was continuously and repeatedly obnoxious.”

Martin had anticipated a debate with the visitors — if not the shouting. The Trump administration had expressed its disapproval of the British plan after details, which should not have been made public for almost another year, were leaked to The Daily Telegraph two weeks earlier by Theresa May’s then defence secretary, Gavin Williamson. He was sacked , despite repeatedly denying being the leaker. He was among a small but vocal group of Conservative MPs who vehemently opposed any involvement from Huawei in the creation of Britain’s 5G network.

Ten years’ distrust

Washington’s hostility to Huawei could be traced back to 2012, when an investigation by the US House intelligence committee concluded that it was a national security threat, because it was unwilling to “provide sufficient evidence” regarding its “relationships or regulatory interaction with Chinese authorities” in Beijing. The Obama administration banned Huawei and another Chinese firm, ZTE, from bidding for US government contracts. Five years later, the Trump administration warned that China’s 2017 National Intelligence Law, which states that organisations must “support, co-operate with and collaborate in national intelligence work”, could force Huawei to snoop for Beijing on countries in which it was operating.

US intelligence agencies and White House officials had repeatedly lobbied all members of the Five Eyes to ban Huawei on national security grounds. While New Zealand had followed Australia and banned the Chinese telecoms company in November 2018, Canada was still considering its options, and would not announce its intention to ban Huawei until May this year. The US secretary of state, Mike Pompeo — a director of the CIA during the early days of the Trump administration — had declared in a thinly veiled warning to Britain in February 2019 that countries using Huawei equipment were a risk to the US. Staff from his office were also reminding their counterparts in Britain that they were risking their place in the Five Eyes should the UK decide to approve Huawei.

In May 2019 — the same month Pottinger flew to Britain for the meeting at the Cabinet Office — the US president signed an executive order to prohibit Chinese companies, including Huawei, from selling equipment in America because of the “undue risk of sabotage” and “catastrophic effects” on communications systems and infrastructure. The Department of Commerce placed Huawei and 68 of its affiliates on a trade blacklist for “activities contrary to the national security or foreign policy interests of the United States”.

Martin gave Pottinger assurances that Huawei’s work on the 5G network would not compromise the UK’s intelligence-sharing channels with the Five Eyes, government systems or nuclear facilities, because such sensitive areas were linked to computer networks inaccessible to Huawei. Such guarantees were not enough to appease their Americans during — or after — their meeting in London.

Lord Darroch, who served as Britain’s national security adviser before becoming the UK’s ambassador in the US in January 2016, said the US delegation “didn’t really have any compelling technical arguments that undermined the GCHQ case. I remember GCHQ seeming pretty unimpressed. The encounter exposed that the US case was really political, not technical. So GCHQ stuck to their guns, and, initially, so did the prime minister.”

Theresa May, who was prime minister until July 2019, said: “Any decision taken by a politician can by definition be described as a political decision, but this was not a decision based on politics. It was based on the fact that we believed that . . . we had the capability of ensuring that we could protect what needed to be protected.”

The unshakable position on Huawei held by the US officials was particularly insulting to their British colleagues, because GCHQ had spotted a technical threat in the Chinese company’s products two years before the company had been banned by the White House. In fact, GCHQ had created an oversight facility in Banbury, Oxfordshire, to identify any risks associated with Huawei’s products. The only reason for not excluding the Chinese company altogether was because its products were significantly cheaper than those of its competitors, Nokia and Ericsson.

The CIA tried to discredit the UK’s position on Huawei in the eyes of its European allies. Officers from the agency’s Belgium station met their counterparts in the French, German, Italian and Norwegian intelligence services, among others, to express their concerns about the UK’s “misjudgment”. British intelligence officials were outraged by what they described as a “black ops” mission facilitated by the CIA — some even calling it a betrayal of friendship. Yet again, the special relationship between London and Washington had been strained and risked being permanently disrupted.

On July 14, 2019, two months after his team clashed with Pottinger in London, Ciaran Martin travelled to Washington with Britain’s national security adviser, Mark Sedwill, to meet US officials at the White House. Among those present were Pottinger and John Bolton, Trump’s latest national security adviser. Notably missing was Sir Kim Darroch, the ambassador, who had been handling the crisis behind the scenes but had been forced to resign a few days earlier after leaked emails revealed he had described Trump as “incompetent”, “insecure” and “inept” in cables he had sent to London shortly after the president had been elected to office.

During the hour-long meeting, Bolton reassured Martin and Sedwill that he was sympathetic to the UK’s assurances and said he would ask members of his own security council to devise a plan that would help resolve their differences over Huawei. Pottinger seemed largely deferential to Bolton during the meeting, and the aggression he had shown in London had all but disappeared. Perhaps it was because he knew the US had a trick up its sleeve.

The new prime minister, Boris Johnson, had supported Martin’s recommendations on dealing with the Chinese telecommunications giant. In January 2020, he gave Huawei limited approval to build the 5G network, but with more limitations, excluding it from access to military and nuclear sites and national infrastructure. Huawei would be allowed to build only the parts of the network that connected equipment and devices to phone masts.

Britain’s defiance was met with the ultimate checkmate. Trump introduced further sanctions in May 2020 that banned Huawei from using US-made chips in its equipment. As a result, Martin could no longer guarantee the security of Huawei’s products, and two months later, in a remarkable public U-turn, Johnson finally banned Huawei from operating in Britain. His move would delay the country’s 5G rollout by up to three years and cost it at least £2 billion to remove all Huawei 5G equipment from its networks by 2027.

Pompeo welcomed Johnson’s decision, saying: “The UK joins a growing list of countries from around the world that are standing up for their national security by prohibiting the use of untrusted, high-risk vendors.” Pottinger must have also been cheering. Not only had his opposition to Huawei’s role in Britain come to fruition, but by the time it did, Trump had promoted him to deputy national security adviser.

“There was a lot of media speculation and parliamentary interest in whether we would ban Huawei or not,”’ said Darroch. “In my time, GCHQ had led on detailed analysis about the risk from Huawei kit on the communications network and had concluded that, provided it was not at the core of the network, it was OK. This analysis was a central part of the discussion at the national security council and key to the then-agreed outcome that Huawei equipment could be used in certain parts of the network. It was basically driven by the analysis of GCHQ . . . It would be legitimate to do it [drop Huawei] for political reasons, or because it was so important to the Americans, or as an expression of Five Eyes solidarity, or whatever. But it shouldn’t be dressed up as technical.”

Martin stepped down as head of GCHQ’s National Cyber Security Centre in September 2020 to become a professor at Oxford University’s Blavatnik School of Government. He maintains that his confidence in the plan for Huawei to help build the country’s 5G network had always been underpinned by technical assessments, and he had been under no illusions about the potential risks that Huawei posed.

“In reality, anyone can have a go at hacking anything,” he said. “We in the UK, thanks to the US sanctions, are now entirely dependent on Nokia and Ericsson. For sure, we trust their boards of directors. But are we seriously saying that just because they’re not Chinese, they can’t be hacked? By neighbouring Russia, for example? Or China?”

0 notes

Text

5G wars: the US plot to make Britain ditch Huawei

GCHQ was confident it could work safely with the Chinese tech firm. An American official thought otherwise — and, in a Cabinet Office meeting, shouted about it for five hours

Donald Trump’s arrival in Washington in 2017 had quickly united the Five Eyes spy network against the misinformation emerging from the White House. The assurances given by US agencies to their counterparts in the UK, Canada, Australia and New Zealand proved that the preservation of intelligence-sharing should be safeguarded from politics.

It was a laudable effort — until the CIA and National Security Agency (NSA) sided with White House officials on matters relating to Huawei, the Chinese tech firm with links to the Chinese Communist Party. Britain was determined to engage with Huawei based on a recommendation made by Ciaran Martin, whose team at GCHQ had made detailed intelligence and technology assessments.

A White House delegation arrived in London in May 2019 on a policy-disruption mission. Their brief was to oppose a British plan that would allow Huawei limited access to help build the country’s next-generation 5G cellular data network.

Within minutes of the delegation’s arrival at the Cabinet Office, Martin and other senior officials, including the deputy national security adviser, Madeleine Alessandri, were effectively shouted at by one of their guests for five hours.

That guest was Matthew Pottinger, a former US Marines intelligence officer parachuted into the White House in early 2017 to become the National Security Council’s director on Asia. He was known for his distrust of China’s authoritarian regime, a sentiment shaped during his previous life as a foreign correspondent for The Wall Street Journal in Beijing, where he had been subjected to surveillance and physically attacked by the authorities.

Pottinger’s influence on US policy towards China was immediate on taking up his role. He was described by Steve Bannon, the former White House chief strategist, as “one of the most significant people in the entire US government”. One year into his role, Pottinger had played a key role in the White House’s decision to impose tariffs on $200 billion of Chinese goods. Trump had already declared that “trade wars are good, and easy to win” when he had decided to punish China over, as he saw it, the American jobs being lost to its cheaper workforce. Beijing retaliated with its own tariffs on US products.

While Pottinger and Martin were both in their mid-forties and equally influential in their respective governments, that was pretty much where the similarities ended.

“We were keen to work with the US to counter [China’s strategic] ambitions,” Martin recalled. “The problem was, on our side, we didn’t think Huawei’s limited involvement in UK 5G was the most important thing in a much wider strategic challenge — whereas the US were only interested in that part of the problem, for reasons we couldn’t fathom.”

A British intelligence official who was at the meeting said: “Pottinger just shouted and was entirely uninterested in the UK’s analysis. The message was, ‘We don’t want you to do this, you have no idea how evil China is’. It was five hours of shouting with a prepared, angry and weirdly non-threatening script. We tried to offer a policy discussion but Pottinger didn’t care. We even said that we didn’t contest the analysis of the Chinese threat and explained our technicalities, but the US officials weren’t interested in that. Pottinger was continuously and repeatedly obnoxious.”

Martin had anticipated a debate with the visitors — if not the shouting. The Trump administration had expressed its disapproval of the British plan after details, which should not have been made public for almost another year, were leaked to The Daily Telegraph two weeks earlier by Theresa May’s then defence secretary, Gavin Williamson. He was sacked , despite repeatedly denying being the leaker. He was among a small but vocal group of Conservative MPs who vehemently opposed any involvement from Huawei in the creation of Britain’s 5G network.

Ten years’ distrust

Washington’s hostility to Huawei could be traced back to 2012, when an investigation by the US House intelligence committee concluded that it was a national security threat, because it was unwilling to “provide sufficient evidence” regarding its “relationships or regulatory interaction with Chinese authorities” in Beijing. The Obama administration banned Huawei and another Chinese firm, ZTE, from bidding for US government contracts. Five years later, the Trump administration warned that China’s 2017 National Intelligence Law, which states that organisations must “support, co-operate with and collaborate in national intelligence work”, could force Huawei to snoop for Beijing on countries in which it was operating.

US intelligence agencies and White House officials had repeatedly lobbied all members of the Five Eyes to ban Huawei on national security grounds. While New Zealand had followed Australia and banned the Chinese telecoms company in November 2018, Canada was still considering its options, and would not announce its intention to ban Huawei until May this year. The US secretary of state, Mike Pompeo — a director of the CIA during the early days of the Trump administration — had declared in a thinly veiled warning to Britain in February 2019 that countries using Huawei equipment were a risk to the US. Staff from his office were also reminding their counterparts in Britain that they were risking their place in the Five Eyes should the UK decide to approve Huawei.

In May 2019 — the same month Pottinger flew to Britain for the meeting at the Cabinet Office — the US president signed an executive order to prohibit Chinese companies, including Huawei, from selling equipment in America because of the “undue risk of sabotage” and “catastrophic effects” on communications systems and infrastructure. The Department of Commerce placed Huawei and 68 of its affiliates on a trade blacklist for “activities contrary to the national security or foreign policy interests of the United States”.

Martin gave Pottinger assurances that Huawei’s work on the 5G network would not compromise the UK’s intelligence-sharing channels with the Five Eyes, government systems or nuclear facilities, because such sensitive areas were linked to computer networks inaccessible to Huawei. Such guarantees were not enough to appease their Americans during — or after — their meeting in London.

Lord Darroch, who served as Britain’s national security adviser before becoming the UK’s ambassador in the US in January 2016, said the US delegation “didn’t really have any compelling technical arguments that undermined the GCHQ case. I remember GCHQ seeming pretty unimpressed. The encounter exposed that the US case was really political, not technical. So GCHQ stuck to their guns, and, initially, so did the prime minister.”

Theresa May, who was prime minister until July 2019, said: “Any decision taken by a politician can by definition be described as a political decision, but this was not a decision based on politics. It was based on the fact that we believed that . . . we had the capability of ensuring that we could protect what needed to be protected.”

The unshakable position on Huawei held by the US officials was particularly insulting to their British colleagues, because GCHQ had spotted a technical threat in the Chinese company’s products two years before the company had been banned by the White House. In fact, GCHQ had created an oversight facility in Banbury, Oxfordshire, to identify any risks associated with Huawei’s products. The only reason for not excluding the Chinese company altogether was because its products were significantly cheaper than those of its competitors, Nokia and Ericsson.

The CIA tried to discredit the UK’s position on Huawei in the eyes of its European allies. Officers from the agency’s Belgium station met their counterparts in the French, German, Italian and Norwegian intelligence services, among others, to express their concerns about the UK’s “misjudgment”. British intelligence officials were outraged by what they described as a “black ops” mission facilitated by the CIA — some even calling it a betrayal of friendship. Yet again, the special relationship between London and Washington had been strained and risked being permanently disrupted.

On July 14, 2019, two months after his team clashed with Pottinger in London, Ciaran Martin travelled to Washington with Britain’s national security adviser, Mark Sedwill, to meet US officials at the White House. Among those present were Pottinger and John Bolton, Trump’s latest national security adviser. Notably missing was Sir Kim Darroch, the ambassador, who had been handling the crisis behind the scenes but had been forced to resign a few days earlier after leaked emails revealed he had described Trump as “incompetent”, “insecure” and “inept” in cables he had sent to London shortly after the president had been elected to office.

During the hour-long meeting, Bolton reassured Martin and Sedwill that he was sympathetic to the UK’s assurances and said he would ask members of his own security council to devise a plan that would help resolve their differences over Huawei. Pottinger seemed largely deferential to Bolton during the meeting, and the aggression he had shown in London had all but disappeared. Perhaps it was because he knew the US had a trick up its sleeve.

The new prime minister, Boris Johnson, had supported Martin’s recommendations on dealing with the Chinese telecommunications giant. In January 2020, he gave Huawei limited approval to build the 5G network, but with more limitations, excluding it from access to military and nuclear sites and national infrastructure. Huawei would be allowed to build only the parts of the network that connected equipment and devices to phone masts.

Britain’s defiance was met with the ultimate checkmate. Trump introduced further sanctions in May 2020 that banned Huawei from using US-made chips in its equipment. As a result, Martin could no longer guarantee the security of Huawei’s products, and two months later, in a remarkable public U-turn, Johnson finally banned Huawei from operating in Britain. His move would delay the country’s 5G rollout by up to three years and cost it at least £2 billion to remove all Huawei 5G equipment from its networks by 2027.

Pompeo welcomed Johnson’s decision, saying: “The UK joins a growing list of countries from around the world that are standing up for their national security by prohibiting the use of untrusted, high-risk vendors.” Pottinger must have also been cheering. Not only had his opposition to Huawei’s role in Britain come to fruition, but by the time it did, Trump had promoted him to deputy national security adviser.

“There was a lot of media speculation and parliamentary interest in whether we would ban Huawei or not,”’ said Darroch. “In my time, GCHQ had led on detailed analysis about the risk from Huawei kit on the communications network and had concluded that, provided it was not at the core of the network, it was OK. This analysis was a central part of the discussion at the national security council and key to the then-agreed outcome that Huawei equipment could be used in certain parts of the network. It was basically driven by the analysis of GCHQ . . . It would be legitimate to do it [drop Huawei] for political reasons, or because it was so important to the Americans, or as an expression of Five Eyes solidarity, or whatever. But it shouldn’t be dressed up as technical.”

Martin stepped down as head of GCHQ’s National Cyber Security Centre in September 2020 to become a professor at Oxford University’s Blavatnik School of Government. He maintains that his confidence in the plan for Huawei to help build the country’s 5G network had always been underpinned by technical assessments, and he had been under no illusions about the potential risks that Huawei posed.

“In reality, anyone can have a go at hacking anything,” he said. “We in the UK, thanks to the US sanctions, are now entirely dependent on Nokia and Ericsson. For sure, we trust their boards of directors. But are we seriously saying that just because they’re not Chinese, they can’t be hacked? By neighbouring Russia, for example? Or China?”

0 notes

Text

5G wars: the US plot to make Britain ditch Huawei

GCHQ was confident it could work safely with the Chinese tech firm. An American official thought otherwise — and, in a Cabinet Office meeting, shouted about it for five hours

Donald Trump’s arrival in Washington in 2017 had quickly united the Five Eyes spy network against the misinformation emerging from the White House. The assurances given by US agencies to their counterparts in the UK, Canada, Australia and New Zealand proved that the preservation of intelligence-sharing should be safeguarded from politics.

It was a laudable effort — until the CIA and National Security Agency (NSA) sided with White House officials on matters relating to Huawei, the Chinese tech firm with links to the Chinese Communist Party. Britain was determined to engage with Huawei based on a recommendation made by Ciaran Martin, whose team at GCHQ had made detailed intelligence and technology assessments.

A White House delegation arrived in London in May 2019 on a policy-disruption mission. Their brief was to oppose a British plan that would allow Huawei limited access to help build the country’s next-generation 5G cellular data network.

Within minutes of the delegation’s arrival at the Cabinet Office, Martin and other senior officials, including the deputy national security adviser, Madeleine Alessandri, were effectively shouted at by one of their guests for five hours.

That guest was Matthew Pottinger, a former US Marines intelligence officer parachuted into the White House in early 2017 to become the National Security Council’s director on Asia. He was known for his distrust of China’s authoritarian regime, a sentiment shaped during his previous life as a foreign correspondent for The Wall Street Journal in Beijing, where he had been subjected to surveillance and physically attacked by the authorities.

Pottinger’s influence on US policy towards China was immediate on taking up his role. He was described by Steve Bannon, the former White House chief strategist, as “one of the most significant people in the entire US government”. One year into his role, Pottinger had played a key role in the White House’s decision to impose tariffs on $200 billion of Chinese goods. Trump had already declared that “trade wars are good, and easy to win” when he had decided to punish China over, as he saw it, the American jobs being lost to its cheaper workforce. Beijing retaliated with its own tariffs on US products.

While Pottinger and Martin were both in their mid-forties and equally influential in their respective governments, that was pretty much where the similarities ended.

“We were keen to work with the US to counter [China’s strategic] ambitions,” Martin recalled. “The problem was, on our side, we didn’t think Huawei’s limited involvement in UK 5G was the most important thing in a much wider strategic challenge — whereas the US were only interested in that part of the problem, for reasons we couldn’t fathom.”

A British intelligence official who was at the meeting said: “Pottinger just shouted and was entirely uninterested in the UK’s analysis. The message was, ‘We don’t want you to do this, you have no idea how evil China is’. It was five hours of shouting with a prepared, angry and weirdly non-threatening script. We tried to offer a policy discussion but Pottinger didn’t care. We even said that we didn’t contest the analysis of the Chinese threat and explained our technicalities, but the US officials weren’t interested in that. Pottinger was continuously and repeatedly obnoxious.”

Martin had anticipated a debate with the visitors — if not the shouting. The Trump administration had expressed its disapproval of the British plan after details, which should not have been made public for almost another year, were leaked to The Daily Telegraph two weeks earlier by Theresa May’s then defence secretary, Gavin Williamson. He was sacked , despite repeatedly denying being the leaker. He was among a small but vocal group of Conservative MPs who vehemently opposed any involvement from Huawei in the creation of Britain’s 5G network.

Ten years’ distrust

Washington’s hostility to Huawei could be traced back to 2012, when an investigation by the US House intelligence committee concluded that it was a national security threat, because it was unwilling to “provide sufficient evidence” regarding its “relationships or regulatory interaction with Chinese authorities” in Beijing. The Obama administration banned Huawei and another Chinese firm, ZTE, from bidding for US government contracts. Five years later, the Trump administration warned that China’s 2017 National Intelligence Law, which states that organisations must “support, co-operate with and collaborate in national intelligence work”, could force Huawei to snoop for Beijing on countries in which it was operating.

US intelligence agencies and White House officials had repeatedly lobbied all members of the Five Eyes to ban Huawei on national security grounds. While New Zealand had followed Australia and banned the Chinese telecoms company in November 2018, Canada was still considering its options, and would not announce its intention to ban Huawei until May this year. The US secretary of state, Mike Pompeo — a director of the CIA during the early days of the Trump administration — had declared in a thinly veiled warning to Britain in February 2019 that countries using Huawei equipment were a risk to the US. Staff from his office were also reminding their counterparts in Britain that they were risking their place in the Five Eyes should the UK decide to approve Huawei.

In May 2019 — the same month Pottinger flew to Britain for the meeting at the Cabinet Office — the US president signed an executive order to prohibit Chinese companies, including Huawei, from selling equipment in America because of the “undue risk of sabotage” and “catastrophic effects” on communications systems and infrastructure. The Department of Commerce placed Huawei and 68 of its affiliates on a trade blacklist for “activities contrary to the national security or foreign policy interests of the United States”.

Martin gave Pottinger assurances that Huawei’s work on the 5G network would not compromise the UK’s intelligence-sharing channels with the Five Eyes, government systems or nuclear facilities, because such sensitive areas were linked to computer networks inaccessible to Huawei. Such guarantees were not enough to appease their Americans during — or after — their meeting in London.

Lord Darroch, who served as Britain’s national security adviser before becoming the UK’s ambassador in the US in January 2016, said the US delegation “didn’t really have any compelling technical arguments that undermined the GCHQ case. I remember GCHQ seeming pretty unimpressed. The encounter exposed that the US case was really political, not technical. So GCHQ stuck to their guns, and, initially, so did the prime minister.”