#War history

Text

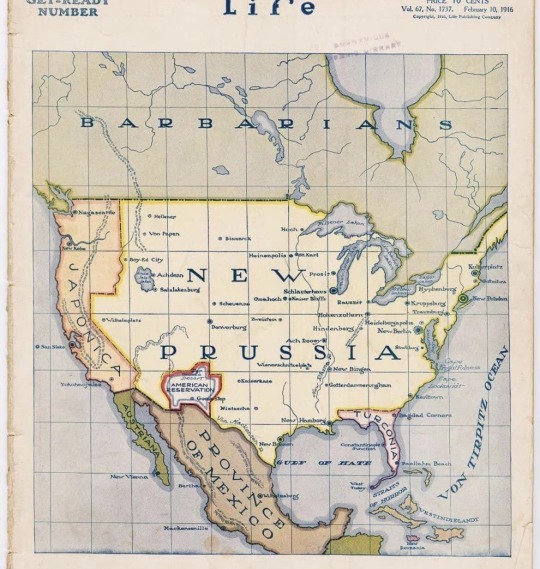

Propaganda made by the allies of WW1 of what could happen to the United States if the Central Powers won.

#world war one#first world war#wwi#canadian history#canada#war history#world war#ww1#world war 1#world history#great war#The First World War#The Great War#1918#1917#1916#1914#1915#germany#german army#historical photos#history#British history#british army#military history#cgwc#remembrance day#canada remembers#november 11

10K notes

·

View notes

Photo

In various cities of the Ancient Iberians (Ancient Iberians were the indigenous cultures that lived in the Eastern coast of the Iberian peninsula before they got conquered by the Roman empire), archaeologists have often found skulls perforated by a nail. All of them have been found in the cities located in what nowadays is the Northern half of Catalonia (Ancient Iberian cultures, though related to each other, varied a lot area to area).

These are believed to be the skulls of their enemies, who were captured and beheaded. The enemy’s heads were nailed to the city walls or above the entrance door to houses, together with their weapons. Most of these heads belonged to individuals of the male sex, though some are female and a few belonged to children.

The Ancient Iberian language hasn’t been deciphered and their contemporaries didn’t write much about them, thus many aspects of their culture aren’t known for certain. Archaeologists have the hypothesis that this practice could be related to the way Celts exhibited the heads and hands of their enemies as war trophies, or related to a belief present in the ancient Mediterranean according to which cutting someone’s head off stopped them from reaching immortality. The Gauls even passed down the beheaded heads of their enemies to their children, as a prized possession that brought prestige. It’s a possibility that Northern Iberians were in touch with this practice.

Photos from the Ancient Iberian site Ullastret (Comarques Gironines, Catalonia) posted on National Geographic. Information from Rovirà i Hortalà, 1998 and MAC Ullastret.

#història#arqueologia#ullastret#catalunya#ancient iberians#antiquity#ancient history#ancient#archaeology#archeology#protohistory#war history#historical#historical artifacts#artifacts#anthropology#bones#european history#europe

115 notes

·

View notes

Text

MARY SEACOLE // NURSE

“She was a British-Jamaican nurse and businesswoman who set up the “British Hotel” behind the lines during the Crimean War. She described the hotel as a “mess-table comfortable quarters for sick and convalescent officers”, and provided succour for wounded servicemen on the battlefield, nursing many of them back to health. She was posthumously awarded the Jamaican Order of Merit in 1991. It has been argued that Seacole was the first nurse practitioner (in the sense of a practicing nurse with advanced medical skills).”

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bernard Meninsky (British/Ukrainian,1891–1950) • Victoria Station, District Railway IWM • 1918 • Imperial War Museums, UK

#art#painting#fine art#art history#bernard meninsky#british/ukrainian artist#war history#british culture#genre scene#history painting#early 20th century british art#artwork#ww i#pagan sphinx art blog#art lovers on tumblr#art blogs on tumblr#oil painting

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

US Soldier Shakes Hand With A Dog In Luxembourg During The Battle Of Bulge, 1944.

173 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Basics Of American Revolutionary War Uniforms:

Basic descriptions I wrote of each layer of a Continental Army soldier's uniform in order of what you'd put on first to what you'd put on last, starting with:

Shirts:

In the 18th century, a man with a shirt was considered naked, so the shirt was a part of every outfit (although it was often covered in other layers of clothing). The shirts worn by the soldiers in the revolution were designed to be as comfortable as humanly possible, so they were very long, often stopping mid-thigh or just below the knee, loose and flowy, and had lots of ruffles at the top. Shirts also had long, puffy sleeves. The shirts were so comfortable that they would function as nightgowns too. All a man had to do to get ready for bed was take off all of the other layers of his uniform. The shirts were plain white or a yellowish colour, depending on how many times they'd been worn. Collars were high but not as high as collars in the 1790s, and sleeve cuffs were either closed by cuff links (little button things) or they'd just have cute lace at the end. Contrary to some ridiculous but funny assumptions I've heard from people who don't study historical fashion, shirts were not hard to put on, and they were simply pulled over the wearer's head like you would put on any other shirt. Shirts were closed together using buttons (a favourite of mine), linen, thread ties, or different combinations of the forementioned. Buttons tended to be small and made out of either thread, horn, leather, or even leather. Because the shirts were made out of soft, thin materials such as linen, cotton, and light flannel and were worn all the time, they were usually the first clothing items to wear out and break. Due to supply problems, there were periods of time during the revolution where men had to wear their breaking shirts and couldn't replace them. Another thing about shirts that I read somewhere (can not find the source for the life of me) is that Washington told his soldiers to wear hunting shirts because he felt that they were practical in every kind of weather. However, the site did say that they only wore them towards the start of the war and in certain regiments.

Neck accessories (for lack of a better term):

Like I briefly mentioned with the shirts, people in the 18th century had a really weird idea of what counts as naked, and they believed that a man without any kind of neck covering over his shirt was still naked. Cravats and neck stocks were two commonly worn neck garments during the revolution. Cravats were made out of silk, linen, or cotton and could be put on in a range of different ways. When they were untied, they were simply long strips of fabric. There are many ways to tie a cravat. I'm not very good at explaining things, so if you need to figure out how to tie an 18th-century cravat, I recommend looking up a YouTube tutorial. Cravats could also be accessorised with cute brooches and such. There were two different, commonly worn in the continental army, types of neckstock in the 18th century. Number 1 was made of the same materials and had the same colour as a cravat, but number 2 was dark in colour and made of leather. The biggest difference between neckstocks and cravats is how you put them on. Neckstocks aren't meant to be tied like cravats; they have a buckle on one end, so they're meant to be put on more like a belt. Oh, and in case you're wondering, the buckle always goes at the back.

Stockings:

Oh my god, I could talk about revolutionary war stockings forever. They're actually so adorable and cutesy, and I just love them. So the stockings are the pretty little white tights that the 18th century seems to be known for, and they were mainly made via knitting and were made out of either wool, cotton, linen, silk, or a fabric blend of any of the aforementioned. Stockings were usually made using knitting machines, but there were still plenty of people who made them by hand. Stockings in the 18th century were not at all short either; they went above the knee (so basically thigh highs). One of my favourite parts about 18th-century stockings is the garters that secure them into place. The garters were belt things that would wrap around their legs to make sure the stockings wouldn't fall down, and they were usually made out of leather, cloth, lace, or a ribbon tied into a bow. I physically cannot speak of these things without saying aww in my mind.

Culottes:

Also known as knee-breeches, but lets be honest, culottes sound cooler. The culottes worn by 18th-century soldiers were a bit different; instead of having a line of visible buttons at the crotch area to put the culottes on like jeans, they had fewer buttons—usually about 1 or 2—at the top of the culottes, and those buttons would be hidden by the waistcoat. Culottes in the Revolutionary War had a much higher waistband; most culottes in the 18th century had a low waistband, but culottes of the Continental Army had a waistband that went just above the soldiers actual waist. And culottes never stopped lower than the shinbone (to show off the stockings). Culottes were white or off white and were made of either buckskin, elk, sheepskin, wool, linen, velvet, silk, or fabric blends of any of the aforementioned. Culottes were very tight because they were worn so that when the soldiers were riding their horses, which they did a lot, the horse needed to feel every movement of the leg so that it could understand what the rider wanted it to do, and that was much harder if the rider was wearing super loose, flowy pants. Culottes were closed at the side of the knee with more small buttons or ties. Buttons on culottes were usually made of either metal, leather, or horn and covered in cloth or wrapped in thread.

Waistcoats:

Although waistcoats with sleeves did exist in the 18th century, they weren't as popular as waistcoats without sleeves. Going back to the weird 18th century undestanding of what is nude, a man wearing breeches, a shirt, a cravat or neckstock, and an unsleeved waistcoat would still be counted as naked. This is one of the things I see a lot of period dramas get wrong. I understand the overcoat-less look looks cool and attractive, but in the 18th century, that would be like a man going outside wearing no clothes. Oh, and another thing that a lot of period dramas mess up on is that men did not show their shirt sleeves in public; that was considered crude and abnormal; it wasn't illegal, just something you'd get judged for. There were two sub-types of waistcoats: double-breasted and single-breasted. These sub-types actually have nothing to do with breasts at all. In fact, the sub-types are about buttons. Double-breasted means a waistcoat with two rows of buttons, and single-breasted means a waistcoat with one row of buttons. Back to the uniform of the continental army, at the start of the revolution, soldiers wore single-breasted waistcoats in the most popular style of the 1750s and 1760s, but by the end of the revolution, they'd switched to wearing the 1770s style waistcoat, just going by a general pattern I've seen in changes to parts of the uniform. I'm assuming that the switch would have happened in 1779. In case you're wondering, the difference between the 1750s–1760s style and the 1770s style is their length; the former stopped mid-thigh, the latter stopped just below the hip. Waistcoats were usually made of linen, wool, velvet, silk, or a fabric blend of any of the aforementioned. They were made with all different colours and patterns, but in the continental army, they wore beige and off-white waistcoats. The waistcoat buttons were made of horn, metal, or leather and were sometimes wrapped in thread or fabric to make them the same colour as the waistcoat.

Sashes:

Sashes are a detail of the continental army uniform that I see a lot of people (and sites explaining the layers of the uniform) skip over. Continental army sashes were very important because they showed the wearer's position in the army. Green means the wearer is an aide-de-camp or brigade major; pink means the wearer is a brigadier general or a major general; and finally, blue means the wearer is a commander-in-chief. This system was made by Washington in 1775 and was used by the army throughout the war. The sashes were likely made using silk or wool. There was another, separate system with sashes; colonels, lieutenant colonels, majors, captains, sub-alterns, serjeants, and corporals could wear a red sash around their waist. However, this system was likely an optional thing because I've seen many portraits of men in those ranks from 1775–1779—they ditched the system in 1779—and I've seen only one of them where the person is wearing one of the red waist sashes.

Overcoats:

At this point, you are no longer considered naked; congratulations. So there were two kinds of overcoats in the 18th century: frock coats and dress coats. Dress coats were for super-rich people, and frock coats were for everyone else. Dress coats didn't have functional pockets, and the only reason why people thought that they were better than a frock coat was that they were expensive and sometimes prettier. Frock coats had a double-breasted front (same definition as with the waistcoats), functional pockets, and a high, round neckline. You can probably guess what kind of coat the soldiers of the Continental Army wore. They wore blue wool and linen frock coats with large gold or silver metal buttons on the cuffs and facings. George Washington and his officers wore buff-coloured facings with thick buff-coloured cuffs, and most other officers wore red facings with red cuffs. The coats had coattails and stopped midthigh, but the whole button and facing thing stopped just below the hip. The overcoats had this interesting triangle coat tail design thing at the back that I tried to figure out how to describe, but I couldn't. Here's a picture of what I mean by the two different kinds of frock coats worn by the soldiers that I mentioned in this paragraph: the one on the left is the one worn by Washington and his officers, and the one on the right is the other one:

[image credit, Samson Historical and Common Threads: Army]

I have just been told the name of the triangle things, they're called vents and they're to make sure the soldiers could ride horses without messing up their uniform. :)

Epaulettes:

The epaulettes serve the same purpose as the sashes: to declare the wearers rank; however, epaulettes are much more confusing because the epaulette system changed halfway through the war. So, the epaulette system for 1776–1779 goes like this: commanders, major-generals, brigadier generals, colonels, lieutenant-colonels, and majors wore a gold epaulette on each shoulder; captains wore a single gold epaulette on their right shoulder; sub-alterns wore a single gold epaulette on their left shoulder; serjeants wore a red epaulette made of cloth on their right shoulder; and corporals wore a green epaulette made of cloth on their left shoulder. The system from 1779-1784 goes like this, commanders wore a gold epaulette on each shoulder with 3 silver stars, major-generals wore a gold epaulette on each shoulder with 2 silver stars, brigadier-generals wore a gold epaulette on each shoulder with 1 silver star, colonels, lieutenant colonels and majors wore a gold epaulette with no stars on each shoulder, captains wore a gold epaulette on their right shoulder, sub-alterns wore an epaulette on their left shoulder, senior non-commisioned officers wore a red epaulette made of cloth and adorned with a crescent moon shape made of brass on each shoulder, sergeants wore a red epaulette made of cloth on the right shoulder, corporals wore a green epaulette made of cloth on their right shoulder and lastly, privates wore no epaulettes.

Hats:

Tricorn, bicorn and round were a must. Round hats were hats that were cocked on one side, bicorn hats were hats that were cocked on two sides and tricorn hats were hats that were cocked on three sides. Most of the time Continental army soldiers pinned them and folded them on the sides. Soldiers carrying muskets wore the hat in a different way to normal civillians, civillians would have the hat the normal way, center point forward but when carrying a musket over their shoulder, soldiers would turn their hat so that the left part was facing forward. In this position, the two sides of the hat would be almost flat so they could sling their muskets over their shoulders without having to worry about knocking their hat off. The hats white edges were made using worsted wool braid and the hat itself if expensive was made of beaver felt or camel's down painted black and if it was cheap it was just made of black wool felt. Hats were not always worn, I'd say they were more of a formality because I have seen very few portraits of soldiers wearing them.

Hat Cockades:

Hat cockades were made of ribbon or wool and were a sort of decoration to be pinned to the wearer's hat. They were like sashes and epaulettes; they indicated the wearer's rank in the continental army. And the system changed in 1779. So the system before 1779 worked like this: subalterns wore a green hat cockade, captains wore a yellow hat cockade, majors and brigade majors wore a red hat cockade, colonels wore a pink hat cockade, and lieutenant colonels wore a green hat cockade. In 1779, they changed it to honour and celebrate America's military alliance with France, so the colourful insignia were removed, and instead every soldier, regardless of rank, wore a plain black and white hat cockade. French soldiers had a cockade with black in the middle, surrounded by white, and American soldiers had a cockade with white in the middle, surrounded by black. Later on, in 1783, the black and white cockades were named the union cockades and were to be worn on the left breast, close to the heart.

Shoes:

There were actually a few periods of time during the war where some of the soldiers didn't have shoes, such as during the Christmas Day crossing and the winter of 1777–1778. But when they were supplied with shoes (most of the time they were), they wore one of two styles. The classic 'little lad' shoes, as I call them, and riding boots 'Little lad' shoes were shoes made with black leather and secured with a buckle. Little lad shoes had a small heel bit at the bottom, likely meant to make the wearer look taller because, despite tall people being considered the most attractive, most people in the 18th century were very short. Riding boots had an even higher heel and a part at the top of the boots that could be rolled down to fit the wearer. When rolled down, they just look like normal riding boots but with brown cuffs at the top. Interesting shoe-related fact that I thought would be cool to put here: in the 18th century, they didn't make right or left shoes; they made what they called straights, and you were meant to switch which foot you wore them on every day to 'wear them off evenly'. Riding boots were made with leather and were black on the outside and brown on the inside. Riding boots were very tall (they went under soldiers' kneecaps) and worn for the same reason as culottes, to make horse riding easier. It's meant to prevent saddle pinching, have a sturdy toe to protect feet while on the ground, and have a big heel to prevent slipping through stirrups.

Hair:

Originally I planned on not mentioning it on this list because it's not something that you can wear but there were uniform rules about hair in the continental army so I guess it is technically part of the uniform. In the 18th century they viewed men with facial hair was considered wrong and unusual in normal day-to-day life so if course it wasn't acceptable in a military setting. In the continental army they had a rule that men needed to shave every three days. They went against this rule a few times but only when they were desperate. Now on the topic of hair as in, not facial hair, the hair on their head was usually tied into a low ponytail with a blue ribbon or - for some men - cut short. 18th century men LOVED their long hair and did not want to cut their hair short even though they were told it should prevent lice. Wigs and hair powder were fashionable in the 18th century but not many men could afford wigs and it's not like they had a ridiculous supply of hair powder so most of the time they had their natural hair colour showing.

It's important to note that this is just the standard uniform that most men wore; each regiment had its own unique uniform, so if your project has anything to do with a specific regiment, either do your own research or ask me about it in the comments or my asks. This is also post-1775 because 1775 had no uniform. If I have gotten anything wrong, please do not feel afraid to correct me in the comments, and I'll edit the post.

Sources:

https://historyofmassachusetts.org/uniforms-revolutionary-war-soldiers/

https://www.srcalifornia.com/flags/revuniforms1.htm

https://www.bostonteapartyship.com/uniforms-of-the-american-revolution

https://ufpro.com/blog/american-revolutionary-war-study-military-uniforms-across-battlefield

https://www.washingtoncrossingpark.org/continental-army-clothing/#:~:text=Over%20their%20shirts%2C%20soldiers%20would,unit%20a%20soldier%20belonged%20to.

https://www.crazycrow.com/site/tricorn-hat-history/

https://www.si.edu/object/george-washingtons-uniform%3Anmah_434863#:~:text=This%20blue%20wool%20coat%20is,buff%20wool%2C%20with%20gilt%20buttons.

http://www.colonialuniforms.com/revolutionary-war-coats.html

https://www.berkleyhistorical.org/revolutionary-war-uniform

https://www.samsonhistorical.com/en-ca/products/mens-riding-boots

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Riding_boot

#american revolution#american revolutionary war#amrev#american history#revolutionary war#history#historical fashion#fashion history#18th century#18th century fashion#continental army#military history#military uniforms#war history#war of independence#On-partiality's rambles

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

The D-Day invasion began in the pre-dawn hours of June 6 with thousands of paratroopers landing inland on the Utah and Sword beaches in an attempt to cut off exits and destroy bridges to slow Nazi reinforcements.

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Infantrymen of the Third US Army staying close to the wall as they advance through the rubble-strewn streets of Echternach, Luxembourg, February 7th, 1945.”

Source: https://tinyurl.com/Wwii-soldiers

#ww2#ww2 history#world war 2#world war ii#history#western front#american soldier#ww2 photo#war history#wwii history#wwii#wwii era

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Albina Mali-Hočevar, born in Vinica on the 25th of September 1925 Albina was a Slovenian resistance fighter who fought for the liberation of Yugoslavia during World War Two (photo c1945)

After Germany invaded Yugoslavia in 1941 Albina joined the people’s liberation movement at just 16, though she was originally chosen to be a nurse Albina fought in multiple battles, she ended up wounded twice when she was 17 and went on to be wounded again three days after her 18th birthday because of a exploding mine. Albina continued fighting and working till the end of the war as a nurse (suspected to have even worked as a flying nurse) and lived until she was 75yrs old.

Some years later she was recognised for her bravery and was awarded the Yugoslavian Order of the partisan star, 3rd class.

Said in accounts of Albina while she worked as a nurse:

"The nurse Alina always paid more attention to the wounded than to herself"

"She knew neither fear nor exhaustion while there were wounded [partisans] to be taken care of”

#talking history#Albina Mali-Hočevar#world war two#the second world war#ww2#wwii#war history#women in history#historical women

428 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Monument of the Nation’s Immortals (Μνημείο των Αθανάτων του Έθνους - Mnimío ton Athanáton tu Éthnus), a monument dedicated to the Greek soldiers who fell in battle, was recently inaugurated. It commemorates the names of all the soldiers who reportedly fell in a battle defending Greece from 1830 until 1974. The monument is in the military camp “Alexandros Papagos” and will be visitable on the weekends.

Source: ΓΕΕΘΑ (Hellenic National Defence General Staff)

#greece#europe#travel#monuments#history#war history#fallen soldier#fallen in battle#battle history#greek facts#greek history#athens#attica#sterea hellas#central greece#mainland

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Canadian infantry in a front line breastwork in Ploegstreet Wood, October 1915.

#world war 1#canadian history#wwi#historical photos#world war one#war history#military history#The Lost Generation#The wars#the Battle of the Somme#ww1#history#black history month#ww1 stories#ww1 portrait#The Great War#The First World War#1918#1917#1916#1914#Battle of the Somme

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

when ur card declines at therapy so they play day after tomorrow by Tom Waits and force u to think about all of the men in early 20th century wars who had no idea what they were getting into only to leave a completely changed person or not even live to see themselves change

#hoping this is a universal experience#day after tomorrow#tom waits#wwii#wwi#band of brothers#the pacific#all quiet on the western front#1917#hacksaw ridge#saving private Ryan#hbo war#war history

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Women testing weapons at Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland, 1942.

Photographed by Bernard Hoffman and Myron Davis for the February 1, 1943 issue of LIFE Magazine.

"The women come from everywhere. Many have husbands in the Army. Others have husbands who also work at Aberdeen. They wear bright-colored slacks, and their ‘firing fronts’ are a rippling blend of pink, blue and orange, mixed with white and black powder from the guns. They serve on crews of all weapons up to the 90mm A.A.’s [anti-aircraft guns]. They handle highly technical instruments. They drive trucks, act as bicycle messengers, swab and clean vehicles."

#women#old photos#1940s#*#feminism#life magazine#bernard hoffman#myron davis#women in history#artillery#guns#wwii#wwii history#historic photographs#vintage#history#world war ii#women in war#40s#world war 2#photography#old photography#black and white photography#b&w photography#war photography#war history#b&w#black and white

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

El Canyeret neighbourhood in the city of Lleida (capital city of Ponent, Catalonia) devastated after being bombed by Mussolini’s Italian fascist aviation, who was helping Franco and his fascist side in the Spanish Civil War.

Photo source: Arxiu Comarcal del Segrià.

Lleida was bombed many times by the fascist air-force in the Spanish Civil War, most heavily during the days known as “the Battle of Lleida”, between March 27th and April 3rd 1938, which ended in a victory of the fascist side. Lleida was not a big city nor very strategically important -the fascists’ aim was not factories or weapons, but civilians. Lleida’s importance was as a symbol: the rest of Catalonia still resisted as an antifascist stronghold, thanks to the militia organizations that many civilians had joined; but Lleida, as Catalonia’s Westernmost city (and thus the one closest to Spain where Franco’s army already controlled most territory), was the first city in Catalonia that was occupied by the fascist troops. (Remember that one of the main pillars of Spanish fascism are Catalanophobia and Spanish supremacy, and hatred of leftists and atheists, who were also identified with Catalonia because workers’ leftist movements were very strong here.)

The alliance between the Italian aviation, Franco’s Spanish troops and Moroccan troops occupied Lleida for the fascists, and most of the city’s population was either killed or fled as refugees to other parts of Catalonia still under control of the Republic. Out of the 38,000 inhabitants that the city had before the Battle of Lleida, less than 2,000 were left in the city on the day that the fascists considered they had bombed it enough and occupied it by land.

As soon as the fascists took control of the city, they went to erase the official registres of the victims of war, trying to erase responsibility for their massacre. They went to the Civil Registre to take the books of deaths, where the names and dates of the people who died in the city showed how many had been killed by the fascist bombs. The fascists always tried to obfuscate their crimes, they never had any honour even to face their own deeds.

By the way, the neighbourhood shown in the photo (El Canyeret) was home to the descendants of the families that Spanish troops had already destroyed 200 years ago. When Castilla (Spain) first occupied Catalonia, in the year 1714 as the end of the War of the Spanish Succession, the Spanish King Philip V militarized Catalonia, destroying whole neighbourhoods and even whole cities. In the main important cities, including Lleida, the Spanish government destroyed neighbourhoods and built military citadels on its place, that had the cannons always pointing at the population. In Lleida, people were expelled from the slopes of the Seu Vella hill, and the newly-homeless families built shanty towns further down. This was the creation of El Canyeret.

#lleida#catalunya#història#guerra civil#spanish civil war#history#1930s#1930s history#military history#1930s photography#20th century#european history#war history#spain#spanish history#revolutionary catalonia#war of the spanish succession#1714

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

The 105 days of battle of the Winter War ended on 13 March 1940 in a peace treaty signed in Moscow the previous night.

On most fronts, peace had come just in the nick of time. Now the heavy price of this peace was just starting to dawn on the exhausted Finnish population. Bitterness and resentment would remain.

One Soviet soldier asked a comrade with Finnish roots: ‘Tell me honestly, what kind of a character do the Finns possess? … They say the Finns are mean.’ His comrade replied: ‘They are not mean, they just really hold a grudge. They remember who has done them harm in the past. God forgives, the Finns do not.’

This statement would prove to be somewhat prophetic, as less that a year later the two nations would again find themselves at war.

A Finnish ski patrol passing a Soviet OT-130 flamethrower tank at Ruhtinaanmäki on 21 January 1940.

••••••••

Talvisodan 105 päivää kestäneet taistelut päättyivät 13.3.1940 edellisenä yönä Moskovassa solmittuun rauhansopimukseen.

Useimmilla rintamilla rauha tuli aivan viime tingassa. Nyt rauhan raskas hinta alkoi sarastaa uupuneissa suomalaisissa. Katkeruus ja kauna jäivät.

Eräs puna-armeijan sotilas kysyi suomalaisjuuria omaavalta toveriltaan: "Kerropa, millainen on suomalaisten luonne?… Sanotaan että suomalaiset ovat häijyjä." Toveri vastasi: "Eivät he ole häijyjä, he vain kantavat totisesti kaunaa. He muistavat, ketkä aiemmin ovat heitä rikkoneet. Jumala antaa anteeksi, suomalaiset eivät."

Toteamus osoittautui jokseenkin profeetalliseksi, sillä runsaassa vuodessa maat olivat jälleen sodassa keskenään.

Suomalainen hiihtopartio ohittaa OT-130 liekinheitinpanssarivaunun Ruhtinaanmäellä 21. tammikuuta 1940.

••••••••

[ sa-kuva | 3498 | Finland at War/Talvisota 1939-1940 | Talvisota väreissä ]

#wwii#jhlcolorizing#worldwar2#colorizing#wwii history#finland#ww2history#suomi#worldwartwo#ww2photos#winterwar#talvisota#suomisodassa#war history#continuation war#world war 2#wwiihistory#ww2 worldwar2 wwii#historia#history

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Come and See (1985) dir. Elem Klimov

#come and see#Иди и смотри#idi i smotri#Ідзі і глядзі#idzi i hliadzi#elem klimov#aleksei kravchenko#olga mironova#antiwar#war movies#war films#war history#soviet#soviet union#soviet history#ww2#wwii#ww2 movies#ww2 films#wwii movies#wwii films#screencaps#my caps#caps#russian movies#russian films#russian cinema#soviet movies#come and see 1985

673 notes

·

View notes