#a'lelia walker

Text

A'Lelia Walker, daughter of Madame C. J. Walker, observes a facial procedure and gets a manicure at one of her mother's beauty shops in 1920s Harlem.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

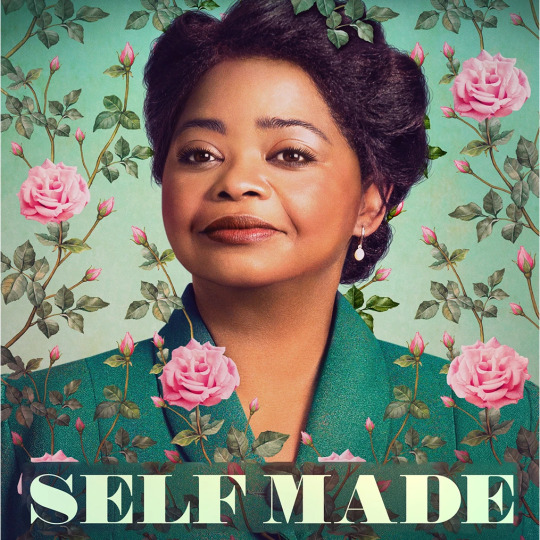

Série: Self Made: Inspired by the Life of Madam C. J. Walker

Criadores: A'Lelia Bundles, DeMane Davis, Eric Oberland, Lena Cordina

Emissora original: Netflix

Ano: 2020

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Claudie's Travel Accessories

Tin for Madam C.J. Walker's Wonderful Hair Grower, 1910s-1920s, Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture

Madam C.J. Walker was one of many Black female self-made millionaires, though she is often described as the first. Another woman who shares the contested title of first Black female self-made millionaire was Annie Malone, who accused Walker of stealing her formula for a hair growth product in the early 1900s.

Before the manufacturing of commercial products, African Americans were forced to rely on ingredients which were inferior substitutions for the palm oil and herbal ingredients that had been used by their ancestors in Africa. These ingredients, which included axle grease, lye, butter, and kerosene caused hair and skin damage, and often led to hair loss.

Regardless of who first invented the formula, the impact that these hair products had on the lives of Black women was massive. Not only did the products improve the health of their hair, but the companies provided thousands of jobs as saleswomen and beauticians, and Walker had a program which taught financial literacy.

Additionally, both Malone and Walker used their millions to support charitable institutions which served African Americans.

By the time Claudie's story is set, Madam C.J. Walker had died, and her daughter A'Lelia was managing the business. If you're interested in another American Girl book with a brief appearance by A'Lelia Walker, I recommend Mystery of the Dark Tower by Evelyn Coleman.

(Please note that I am aware that Madam C.J. Walker was a name she adopted later in life and her birth name was Sarah Breedlove. For clarity's sake, I have chosen to refer to her by this later name.)

instagram

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Black Wall Street USA Historic Legend: Madam C.J. Walker

Madam C.J. Walker was born Sarah Breedlove on December 23, 1867, on a cotton plantation near Delta, Louisiana. Her parents, Owen and Minerva, were recently freed slaves, and Sarah, who was their fifth child, was the first in her family to be free-born. Minerva Breedlove died in 1874 and Owen passed away the following year, both due to unknown causes, and Sarah became an orphan at the age of 7. After her parents' passing, Sarah was sent to live with her sister, Louvinia, and her brother-in-law. The three moved to Vicksburg, Mississippi, in 1877, where Sarah picked cotton and was likely employed doing household work, although no documentation exists verifying her employment at the time.

At age 14, to escape both her oppressive working environment and the frequent mistreatment she endured at the hands of her brother-in-law, Sarah married a man named Moses McWilliams. On June 6, 1885, Sarah gave birth to a daughter, A'Leila. When Moses died two years later, Sarah and A'Lelia moved to St. Louis, where Sarah's brothers had established themselves as barbers. There, Sarah found work as a washerwoman, earning $1.50 a day—enough to send her daughter to the city's public schools. She also attended public night school whenever she could. While in St. Louis, Breedlove met her second husband Charles J. Walker, who worked in advertising and would later help promote her hair care business.

During the 1890s, Sarah Breedlove developed a scalp disorder that caused her to lose much of her hair, and she began to experiment with both home remedies and store-bought hair care treatments in an attempt to improve her condition. In 1905, Breedlove was hired as a commission agent by Annie Turnbo Malone—a successful, black, hair care product entrepreneur—and she moved to Denver, Colorado. While there, Breedlove's husband Charles helped her create advertisements for a hair care treatment for African Americans that she was perfecting. Her husband also encouraged her to use the more recognizable name "Madam C.J. Walker," by which she was thereafter known.

In 1907, Walker and her husband traveled around the South and Southeast promoting her products and giving lecture demonstrations of her "Walker Method"—involving her own formula for pomade, brushing and the use of heated combs.

As profits continued to grow, in 1908 Walker opened a factory and a beauty school in Pittsburgh, and by 1910, when Walker transferred her business operations to Indianapolis, the Madame C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company had become wildly successful, with profits that were the modern-day equivalent of several million dollars. In Indianapolis, the company not only manufactured cosmetics, but trained sales beauticians. © 2014 Black Wall Street USA. These "Walker Agents" became well known throughout the black communities of the United States. In turn, they promoted Walker's philosophy of "cleanliness and loveliness" as a means of advancing the status of African-Americans. An innovator, Walker organized clubs and conventions for her representatives, which recognized not only successful sales, but also philanthropic and educational efforts among African-Americans.

In 1913, Walker and Charles divorced, and she traveled throughout Latin America and the Caribbean promoting her business and recruiting others to teach her hair care methods. While her mother traveled, A'Lelia Walker helped facilitate the purchase of property in Harlem, New York, recognizing that the area would be an important base for future business operations. In 1916, upon returning from her travels, Walker moved to her new townhouse in Harlem. From there, she would continue to operate her business, while leaving the day-to-day operations of her factory in Indianapolis to its forelady.

Walker quickly immersed herself in Harlem's social and political culture. She founded philanthropies that included educational scholarships and donations to homes for the elderly, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and the National Conference on Lynching, among other organizations focused on improving the lives of African-Americans. She also donated the largest amount of money by an African-American toward the construction of an Indianapolis YMCA in 1913.

Madam C.J. Walker died of hypertension on May 25, 1919, at age 51, at the estate home she had built for herself in Irvington-on-Hudson, New York. At the time of her death, Walker was sole owner of her business, which was valued at more than $1 million. © 2014 Black Wall Street USA. Her personal fortune was estimated at between $600,000 and $700,000. Today, Walker is widely credited as the first American woman to become a self-made millionaire.

Walker left one-third of her estate to her daughter, A'Lelia Walker—who would also become well-known as an important part of the cultural Harlem Renaissance—and the remainder to various charities. Walker's funeral took place at her home, Villa Lewaro, in Irvington-on-Hudson, which was designated a National Historic Landmark, and she was buried at Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx, New York.

In 1927, the Walker Building, an arts center that Walker had begun work on before her death, was opened in Indianapolis. An important African-American cultural center for decades, it is now a registered National Historic Landmark. In 1998, the United States Postal Service issued a stamp of Madam C.J. Walker as part of its "Black Heritage" series.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Two films to watch back-to-back before Black History Month is over

My partner and I have been watching movies every Friday night, taking turns choosing (or giving each other a short list that the other person picks from). We either stream from a non-subscription service (such as Vudu or Kanopy) or borrow DVDs from our public library.

As February is Black History Month -- despite Black history being inextricable from American history, and vice versa -- our February selections focused (sometimes distantly) on Black (mostly African-American) history.

After Devil in a Blue Dress (fiction, set in post-WWII LA), selections from a DVD set of early-20th-century African-American cinema (including features by Oscar Micheaux and shorts by Zora Neale Hurston), and Belle (very loosely based on a true story of a Black Englishwoman), we rounded out the month with two films whose makers wound up in court. In my opinion, these films should be seen together, because while the topic is the same, their treatment is complementary.

My Nappy Roots: A Journey Through Black Hair-itage (2008) (33m) is a half-hour documentary by Regina Kimbell. She interviews Black historians and literary figures, describing the historical background and social forces influencing how Black Americans deal with their hair in a white-dominated society. The common question answered by many of the interviewees: What does the (usually insulting) word "nappy" (as applied to hair) mean to you?

(Note: One commentator remarks, incorrectly, that Black people in America are the only people who have had to deal with the political implications of hairstyles. While certainly this became a fraught issue for Black Americans in the 1960s and '70s, with the height of the "Afro" era, Scottish writer Charles Mackay, in his 1841 book Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds, has an entire chapter on the "Influence of Politics and Religion on the Hair and Beard.")

My Nappy Roots is interesting and informative. Photographs and engravings of African women with elaborate traditional hairstyles are shown. The film even mentions Madam C. J. Walker's lesser-known but influential mentor (and later rival) Annie Malone. Unfortunately, there were no DVDs of My Nappy Roots available in our library system, and the only place we could stream it was on Vimeo: https://vimeo.com/156916436

By contrast, Good Hair (2009) (96m) is a feature-length film narrated by star comedian Chris Rock. Since Rock's film came so close on the heels of Kimbell's, she sued him for stealing her idea after she had shown him her film. Rock claims in his own film that his inspiration was hearing his little daughter ask him, "Daddy, why don't I have good hair?" Kimbell's suit failed in keeping Good Hair from wide release.

Some have said that Rock's treatment of the topic, though longer, is more superficial. I would argue, however, that they are different -- that they cover some of the same territory, but with different enough approaches that they are both worth watching.

Rock's Hollywood connections and HBO backing definitely lead to more razzle-dazzle: While Kimbell interviews Black scholars and journalists, Rock mostly interviews Black celebrities and businesspeople. The only person to appear in both films is A'lelia Bundles. I would argue that while Kimbell goes into more depth on the why, Rock goes into more depth on the how.

Both films cover the dangers of harsh chemical straighteners, but only Rock interviews beauty-parlor clients -- including, horrifyingly, those bringing in their small children for their first "perm". Both films mention braiding and the time and expense involved (although neither does much if anything with the braiding option of having artificial braids sewn to short-cropped natural hair). Rock also takes a deep dive into the "weave" -- the practice of having long, straight hair extensions woven to the scalp. He even goes to India to visit the source of most of the natural hair used in these extensions.

I think Rock spent too much time on the Black-haircare convention in Atlanta, particularly the competition between "star" hairdressers. While I was interested to learn how big this convention was, and how much of the Black-hair-product industry is owned by non-Black owners (particularly Asians), some of the interactions with Asian businesspeople were awkward without being revelatory in the muckraking-journalism tradition; comedian Rock was simply going for the laughs. Since the film is so close to 90 minutes, I have to wonder if the inclusion of the showbiz "final competition" at the convention was to fill up the minutes.

Rock interviewed one actress who had shaved her head because she had suffered from alopecia. This is quite a common problem -- it's something that happened to my own congresswoman, Ayanna Pressley. It also happened to Jada Pinkett-Smith; Rock's making of a film about the vicissitudes of Black hair care, including interviewing an alopecia sufferer, casts a curious light on his poking fun at Pinkett-Smith at a recent Oscars ceremony (incurring the wrath of her husband). All that I can guess is that he misjudged how well she would take the joke.

Unlike My Nappy Roots, Good Hair can be streamed on Vudu or Kanopy; it's also available on DVD, which is how we saw it (on a copy borrowed from our public library). I would recommend seeing both these films -- back-to-back if possible, preferably with the more deeply historical and political My Nappy Roots first. It takes only a little over 2 hours in all to do so.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Self-Made: Inspired By The Life Of Madame C.J. Walker

The Netflix series was inspired by a biography on Madame C.J. Walker, written by A'Lelia Bundles, who was actually the adoptive great-granddaughter of Walker. This series showcases the tumultuous and fantastic life of Walker, who made her way out of an abusive marriage and poverty into being one of the richest and most well-known women in America, managing to do this incredible feat all on her own. Her story is unique, and the Netflix show does not forget to dive into some of the darker parts of Walker’s history, such as her husband Charles Walker’s affairs and the massive ambition that may have ruined much of Walker’s personal relationships. Walker’s story takes place during a pivotal time in Black American history, with Booker T. Washington rising to fame alongside Walker. The series managed to secure three awards from the NAACP Image Awards, as well as a Black Reel TV Award. This series was so crucial to the current era, as black history is sorely lacking in the American school system and the representation of a black female entrepreneur in a pre-civil rights era America is titular to the fight against black oppression in America. Pictured below is the real Madame C.J. Walker, at the height of her hair empire, looking like a woman of status and class. The media from Walker’s life that captures her in photographs is unusual for black media from the era, as the photographs ensure that she is viewed as the elegant, beautiful, and proud black entrepreneur that she was. The images tend to showcase her long hair, as she was her own test subject and by all accounts, her products actually worked, with herself being the before and after photos for the Walker hair empire. Attached below is the link to the Netflix series’ trailer for the show.

Self Made: Inspired by the Life of Madam C.J. Walker | Official Trailer | Netflix

1 note

·

View note

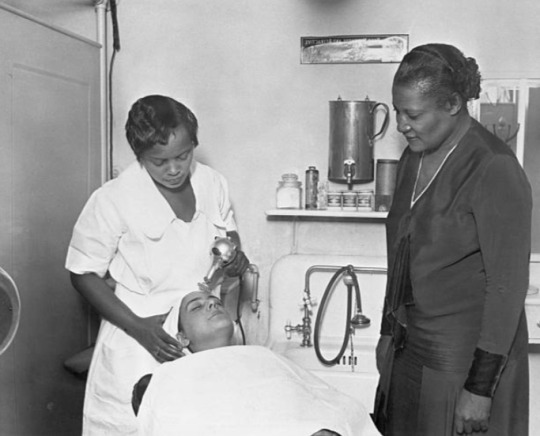

Photo

A'Lelia Walker, daughter of Madame C. J. Walker, observes a facial procedure and gets a manicure at one of her mother's beauty shops in 1920s Harlem.

#madam c.j. walker#a'lelia walker#beauty salon#black owned business#black woman#black women#black business owner#african american#1920s#black people#black beauty#black history#black girl magic#harlem#first self made millionaire#harlem renaissance#vintage#retro#photo#sbrown82

440 notes

·

View notes

Quote

When A'lelia Walker made an appearance, the room stirred in response. She conversed with her guests, wearing a little silk short set, but it might as well been an ermine coat; she had the bearing of a queen, and wore the flimsy little outfit with a stately air. Even without her infamous riding crop, there remained something forbidding and dangerous about her. She smoked and drank with her guests, engaging in small talk. She was a tall, striking woman, who surrounded herself with beautiful women (Ethel Waters, Nora Holt, Edna Thomas) and gay men. She was lavish with her affection and her fortune. Her mother, Madame C.J Walker, had popularized the straightening combs and developed a line of beauty products; every girl in Harlem with straightened, slicked back, bobbed and waved hair had her to thank.

from Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments by Saidiya Hartman

#Saidiya Hartman#Madame CJ Walker#A'lelia Walker#Black feminist theory#the landscape of Black female autonomous sexuality#the landscape of Black male autonomous sexuality#beholding Black intimate geographies#embodiment as grace#GAY GAY GAY

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spoilers!!!!

When I started to watch Self Made, I thought I was getting myself into just a story about Madam C.J. Walker and how she overcame racism, sexism, and betrayals to become the first self-made female millionaire in U.S. I didn't expect to get a queer storyline about her daughter A'Lelia. I'm glad the film didn't make Madam C.J. Walker straight up disgusted by her daughter's actions. Yes, she did disapprove and tried to make her daughter settle down with a man because she wanted a heir. However, she never say her daughter's queer relationships are wrong, sinful, or disgusting. She didn't mind about queer relationships because she only worried about her business. Throughout the film, she had proven many times that she needed no man to help build her empire. She didn't need a man to take care of her daughter, because A'Lelia had already proven to be a capable woman herself in Harlem. She just wanted her daughter to have a child so her legacy can continue.

Bonus: In the end of film, she told her daughter to do whatever she wants because she saw how unhappy A'Lelia was with a man. She accepted A'Lelia's queer nature because she wanted her daughter to be happy. Plus she believed people, especially women have the right to choose to do what they want.

Second Bonus: To fulfill her mother's wish, A'Lelia adopted Fairy and made her the heir.

126 notes

·

View notes

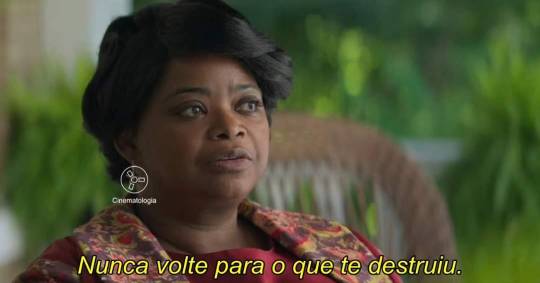

Quote

Never run back to what broke you.

Self Made: Inspired by the Life of Madam C.J. Walker (2020)

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A’Lelia Walker was the daughter of Madam C. J. Walker, the first woman to become a self-made millionaire in America. She was also queer. During the Harlem Renaissance, A’Lelia threw lavish parties attended by princesses and dykes from Europe and Russia.

25 notes

·

View notes

Link

Hurston and Walker were allies in a world where the Black cultural gatekeepers were almost exclusively men. For some, Walker was dismissed as the “Mahogany Millionairess,” her fetes reduced to the whims of a bored heiress with no mind for business. Hurston’s literary contemporaries, including Richard Wright and Ralph Ellison, were dismissive of the writer’s work. Even Langston Hughes, who was a direct recipient of Walker’s financial patronage and had been best friends with Hurston at one point, observed disdainfully, “Girls are funny creatures.”

#black women#the feminist press#black writers#zora neale hurston#a'lelia walker#madam cj walker#black history#black authors

7 notes

·

View notes

Link

#black history#wlw#lgbt#blues music#lucille bogan#ma rainey#bessie smith#ethel waters#big mama thornton#gladys bentley#harry hansberry's clam house#mona's 440 club#alberta hunter#josephine baker#maude russell#mabel hampton#a'lelia walker#ok to reblog#d slur w#q slur w#hist 1920s#hist 1930s#hist 1940s#hist 1950s#readings

129 notes

·

View notes

Text

Director Stanley Nelson & Author A'Lelia Bundles Will Discuss The Life Of Madam C.J. Walker After Screening Of Two Dollars And A Dream Monday Online

Director Stanley Nelson and author A'Lelia Bundles will discuss the life of Madam C.J. Walker and the importance of truthful storyteller this coming Monday. The online event will start with a screening of Nelson's debut work Two Dollar And A Dream which was his 1987 film about Madam C.J. Walker and the first film to look at her life. Bundles is Madam C.J. Walker's great-great-granddaughter and the author of On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker which was used as inspiration for the Netflix series Self Made. Nelson is the grandson of Freeman B. Ransom who was Walker's attorney and the general manager for her hair care company. Nelson interviewed men and women who worked for Walker's company such as former sales representatives, office assistants and executives. He also looked at Walker's role as the first Black philanthropist and her daughter A'Lelia's contribution as a patron of the Harlem Renaissance. This beginning of Nelson's career led to other critically acclaimed films including Freedom Riders, The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution, The Murder of Emmett Till and Miles Davis: Birth of the Cool.

Tina Martin, an Emmy-nominated journalist and host of the WORLD series Local, USA will moderate the discussion. The event happens Monday at 7 PM ET on the World Channel. Viewers can register for the free event here.

0 notes

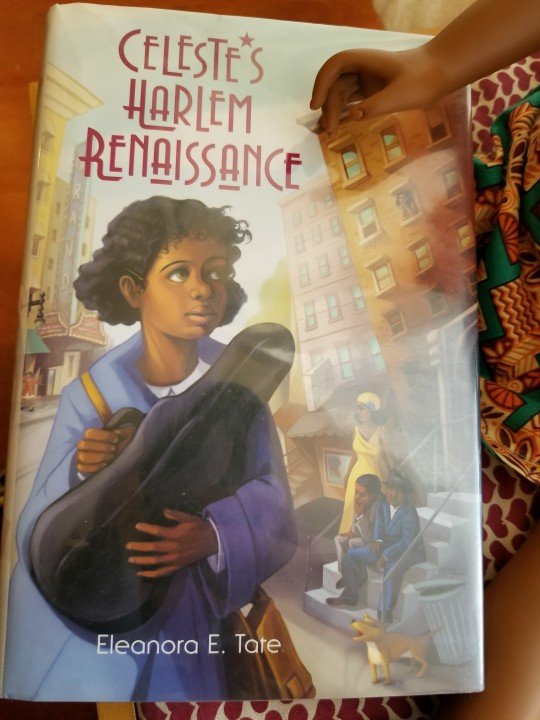

Text

I've heard several folks getting excited about the possibility that American Girl will release a doll, maybe this fall, whose story will be in the Harlem Renaissance.

While that is exciting, none of us doll collectors actually need to wait.

When I first made my Healthy Roots Zoe doll into a 1920s character, it was circumstantial - I wanted to support this small Black-owned doll company at the same time I also wanted to learn more about this time period. But actually, Healthy Roots Zoe doll is a perfect choice for a character from this time period.

The purpose of Healthy Roots dolls and their special doll wig is to teach kids with textured hair how to wash, brush, and style their natural hair. This seems particularly appropriate for a character in the 1920s, around the time that Madam C.J. Walker's hair products were becoming widespread (1920s is after her death but her company was flourishing).

A book that is not the one my doll is based on but would be a great choice to base a doll from this period on is Celeste's Harlem Renaissance by Eleanora E. Tate.

Here's a part of the novel when Celeste meets one of Madam C.J. Walker's salesladies on the train. Celeste, the protagonist, is talking:

" 'Momma said my hair was soft and needed special treatment. She kept it long and sweet-smelling. But... Then my aunt started washing my hair with lye soap, caking it down with lard, and yanking the comb through my hair. The comb ended up with more of my hair than my head.'

Mrs. Hardy shook her head sympathetically. Then she handed me two small jars. 'This shampoo and this salve will help. And this sheet teaches you how to care for your hair and scalp.'

'Oh, thank you!....It's a blessing to have met you,' I told her, 'which is what Momma said when she met nice people.'

'Same to you,' Mrs. Hardy replied."

The story intersects with many historical events and real people from this time period- James Weldon Johnson, Duke Ellington, A'Lelia Walker, the musical Shuffle Along.

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

A beautician styles a customer's hair at the Truman Plaza beauty parlor, 2/12/1990. NARA ID 6460762.

Navy barbers give crew members a trim in the enlisted barbershop on the battleship USS IOWA, 2/1/1986. NARA ID 6420264.

SHOTS AT THE SHOP!

By Miriam Kleiman, Public Affairs

President Biden today announced Shots at the Shop, an initiative to engage Black-owned barbershops and beauty salons nationwide to boost COVID vaccinations and outreach in communities of color. Of course we have related records!

Learn about Madam C.J. Walker, a pioneer of the African American beauty industry and groundbreaking entrepreneur:

A’Lelia Bundles, journalist, historian, author, and National Archives Foundation Board member, is the great-great-granddaughter of Madam C. J. Walker. Bundles' book On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C.J. Walker, was the "inspiration" for Self Made, the 2020 Netflix series.

Madam C.J. Walker in the National Archives - A'Lelia tells Madam Walker's story with help from National Archives records.

Meet Madame C.J. Walker, The National Archives Comes Alive: Young Learners Program.

A’Lelia Bundles Live! - A’Lelia discusses the Netflix series Self Made

USN Air Traffic Controller Airman Shandre Forte receives a fresh haircut from USS Kitty Hawk Ships Serviceman Redmond, 1/13/2001. NARA ID 6610232.

U.S. Navy Ship's Serviceman 2nd Class Darrayll Ezell puts finishing touches on haircut for airman Moses Rodriguez, barber shop aboard Nuclear-Powered Aircraft Carrier USS JOHN C. STENNIS, 1/26/2007. NARA ID 6704265.

#hair#covid#beauty salon#hairstyle#barbershop#get vaccinated#fully vaccinated#shotsattheshop#biden#president#haircuts#hairdo#getvaccienatedcovid19#usnavy#aircraft carrier#a'lelia bundles#a'lelia#madamcjwalker#black history#african american history

69 notes

·

View notes