#agriculture export policy

Text

The immediate impact of the Israeli occupation was to exacerbate unemployment: service jobs for the Egyptian army and UN forces vanished, trade with Egypt halted, and the port was closed. Moreover, since the combined GNP of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip was only 2.6 percent of the Israeli GNP in 1967, they faced inevitable integration into the Israeli economy as the occuption continued. Furthermore, Israeli policies increased the Strip's dependency. These practices included permitting only certain Gaza products to be sold within Israel, flooding the Gaza market with Israeli goods, restructuring Gaza's agriculture, and encouraging Arab laborers to work in Israel.

The Balance and Composition of Trade. After only one year of occupation, 72 percent of Gaza's imports came from Israel; no imports were allowed from Egypt, and 1 percent of its imports came from Jordan (the balance came from Europe). This represented a dramatic shift, since all the prewar trade had been either directly with Egypt or with Europe and Asia through the Gaza port. [...]

A decade later the shift in trading patterns was even more pronounced. [...] 91 percent of imports came from Israel, and nothing was imported from Jordan or Egypt. [...] Dates, strawberries, and vegetables were also sold to Israel, and local industries engaged in subcontracting for Israeli firms.

Agriculture and industry were both hard hit by Israeli competition. Israeli eggs, poultry, and even vegetables sell at lower prices than local produce, and virtually all canned and bottled goods come from Israel. [...]

A 15 percent excise tax and soaring inflation erode the profits of merchants and factory owners. Gazans have no way to hedge against inflation, since the Israeli shekel is the only legal tender on the Strip.

Restructuring Agriculture. Israel has prevented farmers from exporting to Israel any items that compete with Israeli produce and has imposed restrictions on the planting of certain crops. As a result, the output of melons, onions, grapes, almonds, olives, and fish has decreased. Farmers need permits to plant trees and vegetables.

[...] The government has encouraged production of some specialized crops, such as strawberries and dates. Farmers in Beit Lahiya village say that they were ordered to grow strawberries and would otherwise have been prevented from using their land and well. These strawberries are marketed exclusively through Ashkelon port by the Israeli export firm Agrexco. No permits, however, have been given to farmers to plant such crops as mangoes and avocados, which are also grown in Israel.

Arab Labor in Israel. In 1970, 10 percent of the Gaza labor force was employed in Israel, but at present approximately 40 percent (35,000 persons) work there. This includes 25,000 workers who are registered with the official labor exchange and another 10,000 who work illegally. The high unemployment within the Strip and the fact that wages inside Israel were five times those in the Strip made such employment irresistible.

[...] Even those holding regular jobs face difficult conditions. For example, it is illegal for them to remain inside Israel from 1:00 a.m. to 5:00 a.m. But employers and workers collude in circumventing the law so that the workers will not have to spend several hours every day commuting. Farmers let laborers sleep in huts, abandoned buses, or even in the open under the orange trees. In town, workers jam into hostels, sleep on construction sites, or spread out on the floor in restaurants. There have been cases of disasters when workers locked into factories at night were unable to escape when fires broke out. [...]

The overall impact of Israeli economic policy is to turn the Gaza Strip into a large labor camp. The Strip is a source of cheap labor for Israel and its internal economic base is continually eroded.

– 1985. Ann M. Lesch, "Gaza: Forgotten Corner of Palestine." Journal of Palestine Studies 15.1, pp. 43-61. Emphasis mine.

213 notes

·

View notes

Text

Traveling out of any major or mid-size city on the HSR system in China, once you leave the bustling city center, you'll travel through miles upon miles of rural farmland. In China, agricultural is nearly entirely dominated by cooperative farming. Every "village", or a cluster of several farm houses, serves as a hub for the several hundred square kilometers of farmland each coooeraytive operatrs. These agricultural hubs serve as tenporary gransries and logistics centers from which all farming activities are held. During my visit in mid june, the early grain harvest was coming in. Traveling on the HSR, the countryside was adorned with billowing red flags flown from the tractors and harvestors of the cooperatice farms. Inside each cooperative, farmers would bring tgye harvest to a central location to be logged and divided up. A portion would be sold on the market while the rest wiuks go inro rhe national grain reserves. Inside these coorperatives, large red banners advertising and promoting rhye anti-corruption campaign would adorn the walls, encouraging farmers andnlocals to repoet any suspicious or corrupt avtivity to the local COC branch office.

The national grains reserves among other measures is how the CPC eliminated famines from China. Comrade 袁隆平 (Yuan Longping) and his contemporaries and colleagues helped slay one of the horsemen of the apocalypse--famine--by devising a breed of rice which is hardy to drought conditions and yielded high grain output; a technology which China exports to other degeloping nations as a part of BRI and other developmental projects. Additionally, national economic policies which seek to drive down rhe cost of grocies also greatly secure food security for the vast vast majority of the population.

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

Right now, there's an absolute killing to be made by carving up Ukraine, and every western power is trying to grab their piece of the pie.

The military aid going to Ukraine is in the form of loans. Ukraine is gaining about $3 billion in debt for each month of fighting against the invasion. That's 1.5% of the pre-war GDP each month. In reality, the country's GDP has plummeted by 30 - 45%, so, in reality, it's gaining 2.1 % to 2.7% of its GDP in debt each month. The lion's share of this new debt is to foreign creditors, and this debt is expected to pass 100% of Ukraine's pre-war GDP sometime next year.

At the same time, the destruction of country's Soviet-era industrial base, started in 2014, is being completed. This is de-industrialising Ukraine, making it more and more dependent on purchases from foreign exporters. Ukrainian workers are being stripped of their rights, and are forced to flee to the EU with little hope of a return to their homes, providing a reserve army of both educated and desperate labour to the western powers. Spiraling debt, local de-industrialisation, and a flood of cheap workers are all immensely profitable things for the western bourgeoisie.

The debt being accrued is essentially unpayable for the future Ukrainian state, and gives Ukraine's creditors long-term claims on Ukrainian profits and leverage over policy, as well as forcing cuts to Ukraine's public sector. It also necessitates the privatisation of state assets - for example Ukraine's power plants, agricultural land, gas pipelines and rail networks. De-industrialization opens up a market in Ukraine for foreign exporters, and eliminates the power base of the Ukrainian oligarchs, the local competition to international capital. The immiserated workers, additionally, cheapen labour abroad, as well as for future investment in Ukraine itself.

The EU, initially so hesitant about this war, may see a way out of US-domination through the securing of a significant part of Ukraine within its sphere of influence. The US and its junior partners see a massive source of profit and a cudgel to keep the EU in line. The value to Russia is obvious. In brief - every world power involved has something to gain from the complete destruction and desolation of Ukraine, the impoverishment of its workers, and the carving up of its territory.

This is the nature of inter-imperialist war. This is why we say both no to Russia and no to NATO. There is not a single actor in this war who aids the working people of Ukraine.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

The standard legend of India’s Green Revolution centers on two propositions. First, India faced a food crisis, with farms mired in tradition and unable to feed an exploding population; and second, Borlaug’s wheat seeds led to record harvests from 1968 on, replacing import dependence with food self-sufficiency.

Recent research shows that both claims are false.

India was importing wheat in the 1960s because of policy decisions, not overpopulation. After the nation achieved independence in 1947, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru prioritized developing heavy industry. U.S. advisers encouraged this strategy and offered to provide India with surplus grain, which India accepted as cheap food for urban workers.

Meanwhile, the government urged Indian farmers to grow nonfood export crops to earn foreign currency. They switched millions of acres from rice to jute production, and by the mid-1960s India was exporting agricultural products.

Borlaug’s miracle seeds were not inherently more productive than many Indian wheat varieties. Rather, they just responded more effectively to high doses of chemical fertilizer. But while India had abundant manure from its cows, it produced almost no chemical fertilizer. It had to start spending heavily to import and subsidize fertilizer.

India did see a wheat boom after 1967, but there is evidence that this expensive new input-intensive approach was not the main cause. Rather, the Indian government established a new policy of paying higher prices for wheat. Unsurprisingly, Indian farmers planted more wheat and less of other crops.

Once India’s 1965-67 drought ended and the Green Revolution began, wheat production sped up, while production trends in other crops like rice, maize and pulses slowed down. Net food grain production, which was much more crucial than wheat production alone, actually resumed at the same growth rate as before.

But grain production became more erratic, forcing India to resume importing food by the mid-1970s. India also became dramatically more dependent on chemical fertilizer.

According to data from Indian economic and agricultural organizations, on the eve of the Green Revolution in 1965, Indian farmers needed 17 pounds (8 kilograms) of fertilizer to grow an average ton of food. By 1980, it took 96 pounds (44 kilograms). So, India replaced imports of wheat, which were virtually free food aid, with imports of fossil fuel-based fertilizer, paid for with precious international currency.

Today, India remains the world’s second-highest fertilizer importer, spending US$17.3 billion in 2022. Perversely, Green Revolution boosters call this extreme and expensive dependence “self-sufficiency.”

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

The sweeping tariffs that former President Donald J. Trump imposed on China and other American trading partners were simultaneously a political success and an economic failure, a new study suggests. That’s because the levies won over voters for the Republican Party even though they did not bring back jobs.

The nonpartisan working paper examines monthly data on U.S. employment by industry to find that the tariffs that Mr. Trump placed on foreign metals, washing machines and an array of goods from China starting in 2018 neither raised nor lowered the overall number of jobs in the affected industries.

But the tariffs did incite other countries to impose their own retaliatory tariffs on American products, making them more expensive to sell overseas, and those levies had a negative effect on American jobs, the paper finds. That was particularly true in agriculture: Farmers who exported soybeans, cotton and sorghum to China were hit by Beijing’s decision to raise tariffs on those products to as much as 25 percent.

The Trump administration aimed to offset those losses by offering financial support for farmers, ultimately giving out $23 billion in 2018 and 2019. But those funds were distributed unevenly, a government assessment found, and the economists say those subsidies only partially mitigated the harm that had been caused by the tariffs.

The findings contradict Mr. Trump’s claims that his tariffs helped to reverse some of the damage done by competition from China and bring back American manufacturing jobs that had gone overseas. The economists conclude that the aggregate effect on U.S. jobs of the three measures — the original tariffs, retaliatory tariffs and subsidies granted to farmers — were “at best a wash, and it may have been mildly negative.”

“Certainly you can reject the hypothesis that this tariff policy was very successful at bringing back jobs to those industries that got a lot of exposure to that tariff war,” one of the study authors, David Dorn of the University of Zurich, said in an interview.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

SOFIA, Bulgaria (AP) — Hundreds of angry farmers took to the streets in Bulgaria’s capital, Sofia, on Monday to complain of what they called “the total failure” of the government to meet the mounting challenges of the agricultural sector.

They called on Agriculture Minister Kiril Vatev to step down for not keeping his promises to ease the administrative burden on the farming sector, to seek state compensation for high costs and falling incomes.

Like their colleagues elsewhere in Europe, Bulgarian farmers are frustrated with domineering European Union regulations, the hardships stemming from the surge in fertilizer and energy costs because of Russia’s war in Ukraine, the increasing imports of farm products that are flooding local markets and the undercutting of prices.

Ventsislav Varbanov, who chairs the Association of Agricultural Producers, complained that the government is adding more undue burdens, instead of seeking some relief for the farmers.

“Let me remind you that our interests were not protected neither as the Ukrainian goods flooded us," he said, referring to cheaper products exported from Ukraine, "nor had we budget guarantees for the losses we suffered because of the war in Ukraine.”

Varbanov pleaded for a long-term government policy: “We want to know what will be in tomorrow, in the next year, in the next five years.”

Meanwhile, the grain producers’ association announced that its members might join the protests on Tuesday by blocking main roads with their farming vehicles.

The association expressed discontent with a statement made by Prime Minister Nikolay Denkov in response to their demands for compensation that only grain producers who can prove a loss for 2023 will receive financial support. The association wants some form of compensation for all grain producers.

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

ODESA, Ukraine—In his office overlooking Odesa’s Pivdennyi Port on the Black Sea, Viktor Berestenko smiled contentedly at the half-dozen large international cargo ships just beyond the harbor. “It’s as beautiful as your first kiss,” said the grinning president of the Association of International Freight Forwarders of Ukraine. Speaking to Foreign Policy in late March Berestenko was only too happy to inform me that Ukraine’s three free ports—all in and around Odesa—are operating 24/7, and that the country’s grain exports are back to prewar levels.

The restoration of Black Sea trade is a major breakthrough for Ukraine, in stark contrast to the losses it has endured this year on the eastern fronts. In the Black Sea theater, Ukraine has pulled off the unthinkable: beating back the esteemed Russian Navy even though it has next to no naval force of its own.

From the tiny swath of coastline around Odesa, Ukraine has stymied Moscow’s attempt to landlock and hobble its economy by rendering it unable to market its voluminous agricultural exports. In the spring of 2022, the Russian military barricaded Ukraine’s Black Sea ports and brought exports to a standstill. This forced Ukraine to shift to land routes to market its goods and caused worldwide grain prices to spike, which raised concerns about famine in the Middle East and Africa. Today, Russia still occupies 16 Ukrainian ports. But the Black Sea front looks more hopeful for Ukraine than at any time since the war’s onset more than two years ago.

The Ukrainian fleet lost 80 percent of its vessels after the Russian occupation of Crimea in 2014. But, relying a combination of missile systems and unmanned drone boats guided by advanced GPS and cameras, Ukraine’s armed forces claim to have crippled a third of Russia’s Black Sea fleet. They have also upended the Russian supply lines that serve thousands of troops in the occupied areas of southern Ukraine.

On March 24, Ukraine landed another blow, reportedly using U.K.- or French-made air-to-surface missiles, taking out two large Russian landing ships and other infrastructure near the occupied Crimean port city of Sevastopol. Russia’s fleet has suffered such a drubbing that it prompted the firing of its top admiral, Nikolai Yevmenov, in mid-March. Today, Russia’s remaining ships are in docked in berths along the far side of the Crimean Peninsula, out of sight but not entirely out of Ukraine’s reach.

“Russia wanted to turn the Black Sea into a big Russian lake. But Ukraine reversed it,” said Volodymyr Dubovyk, the director of the Center for International Studies at the Odesa Mechnikov National University. “Russian ships today don’t venture into the northwest of the Black Sea.”

This cover has enabled Ukraine to improvise a sea corridor that begins in Odesa and hugs the safe shores of NATO members Romania, Bulgaria, and Turkey as ships travel southwest en route to the Bosphorus Strait, through which most Black Sea trade passes. Exploiting a bumper crop, Ukraine is now exporting as much grain—corn, wheat, and barley—as it did before the war, as well as other goods, and has opened its Odesan ports for nighttime business to handle yet more. Prior to the war, Ukraine traded more grain than the entire European Union and supplied half of the globally traded sunflower oil, as well as iron ore and fertilizer, according to Bloomberg.

“This is enormously important for Ukraine’s economy, for the Odesa region, and for our future,” said Sergey Yakubovskiy, an economist at Odesa National University. “We have to do everything to keep this route open and reliable.”

Ukraine’s asymmetric Black Sea strategy relies ever more upon Ukraine-made drone boats—known as uncrewed surface vessels (USVs)—that speed across the water beneath Russian radar carrying up to 800 kilograms (1,760 pounds) of explosives. These projectiles have sunk or disabled some of the 24 lost Russian warships, evidence that Ukraine’s domestic arms production has been stepped up and is increasingly consequential in the absence of anticipated U.S. and European assistance. According to the Guardian, there are currently 200 drone manufacturing companies in Ukraine, some of them bankrolled by crowdfunding campaigns. In December 2023, they delivered 50 times as many robotic explosives as in the entire year of 2022, according to Ukraine’s Ministry of Digital Transformation.

Ukraine’s strategy is to maintain its presence in the Black Sea with the prospect of soon acquiring the longer-range missiles that it needs to hit Crimea itself and Russia proper beyond it, Dubovyk said. For Ukraine, he explained, the pressing issue is what comes next. “Crimea is in play, and if Ukraine can put more pressure on Russia there, it can make the occupation untenable. It would change the war’s logic if Russia couldn’t supply the eastern fronts from Crimea,” he said.

Russia’s response has been to target Odesa’s ports, energy infrastructure, and housing blocks with ballistic missiles. Seldom does a day pass without air raid sirens in the port city, which send its residents scrambling into their cellars. In March alone, Russian attacks killed 32 civilians.

One would think that the new coastal sea route would obviate Ukraine’s need to access EU markets via land, namely through Central Europe, and thus ameliorate the friction it has caused between the Central Europeans and Ukraine. Following Russia’s invasion, the EU allowed Ukraine tariff-free access to its markets, which had the effect of undermining the Visegrad Group states’ own grain trade and prompting farmers to take to the streets in anger, above all in Poland. Now, logically, trade could revert to its previous routes and the injurious tiff come to an end.

Not so quickly, explained Yakubovskiy, the economist. He pointed out that Ukraine’s new sea corridor is a temporary and unsanctioned byway, possible now only as a result of Russia’s naval weakness and an informal agreement between Russia and Ukraine not to target civilian shipping. It could end at any moment, he said.

As for Russia, it is not likely to improve its Black Sea positions soon. This is because Turkey controls the Bosphorus and Dardanelles straits, and Ankara has chosen to adhere to the letter of the 1936 Montreux Convention, which prohibits the passage of warships through the straights into the Black Sea in a time of war. Russia thus has no way of getting reinforcements to its ports.

The upshot of Russia’s retreat from Black Sea waters and Turkey’s control of the straits has put Ankara in the driver’s seat. Whether Ukraine maintains its new trade route thus depends, to some extent, on Turkey.

In the past, Ankara has shown itself deft at using leverage to promote its own interests, whatever they may be. It could turn Viktor Berestenko’s bliss into a short-lived fling.

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey!!! Since you said you have a lot figured out for your WIPs I'm interested in your answers!!

what natural resources does each nation have that the others don't? do they export/trade it at all? (For any WIP you wanna answer for!)

@bloodlessheirbyjacques 👀❤️🔥

JACQUES, I LOVE YOU!!!!!! I'll try to keep this at least somewhat brief, but be warned, you have NO idea what floodgates you have just opened.

(I actually intended to make a post like this literally over a year ago, so thank you for helping me make it!!)

Get ready for:

Econ 101 - A Crash-Course in Continental Trade Policy

Before we get started, here's some things you might find helpful:

a map of the continent (see below)

an explanation of why Anvia and Oryn don't get along

under the cut because hoo boy, this is a LOT.

Anvia, the kingdom where ATQH takes place (and which Fallon rules) is primarily an agricultural society. The country's position in the middle of the continent, plus the river running through the kingdom providing fertile land, gives makes it the best-suited area for agriculture on the continent.

(Side Note: It gets colder as you got west-northwest on this continent. Oryn is cold, with long winters and short summers, while Oraine is extremely hot and the land dries up quickly.)

They grow crops and raise animals not only for their own survival, but for export to the neighboring nations. Anvia also has a decent number of craftspeople living in its larger cities, who use crop byproducts (or non-food crops) and animal products to make other products, such as textiles, leather products, etc.

Thus, Anvia's main products/exports are food crops (apples, wheat, strawberries, blueberries, raspberries, lettuce, cabbages, carrots, peas, hops, among other things), created food products (wine, ale, baked goods, jams, jellies, preserves) as well as animal products (largely wool, but things like eggs, cheese, and milk may also be exported), and craftsproduts (textiles and leather products, for example).

Due to the fact that most of Anvia is farmland, be it crop fields or livestock pastures, there is very little opportunity for logging. Even the areas that haven't been developed for farming are largely prairie-like areas. Also, Anvia lacks substantial access to mountains or mineral deposits for mining. So they are lacking in construction materials such as timber, stone, and metals.

Oryn, on the other hand, is ripe with construction goods. They have massive mines scattered throughout the kingdom, especially along the mountain range that borders with Anvia. (Ironkeep, the fortress to the Northeast of Westcliff, is a major stronghold built to protect Oryn's most profitable mines.) Additionally, a massive portion of the kingdom is covered in forests, so logging is another major industry.

(Side Note: Kristopher's father and the current king of Oryn, Pierre, has increased both of these industries massively. The working conditions in both tend to be hazardous, with many people being injured or killed. (Fun Fact: If you want to know how Pierre runs his kingdom, listen to Eat Your Young by Hozier.)

Kristopher believes that his father is ruining Oryn, not only by ruining much of its natural land, but also by working the people so hard.)

Notably, Oryn is also home to significant number of craftspeople, specializing in blacksmithing, metalworking, and jeweling. Orynian weapons and armor are said to be stronger and more durable than any others, and jewelry made by Orynian jewelers with Orynian stones is highly prized across the continent and beyond.

Oryn's main exports are lumber, stone, metal (raw, processed, and crafted into items), and jewels (raw, processed, and made into jewelry).

However, what Oryn severely lacks is fertile farmland. Not only is most of the land covered in trees, but the soil is quite rocky -- far from ideal for large-scale farming. (The hilly, mountainous terrain doesn't help.)

So, you can probably see why Oryn and Anvia need each other. They are forced to trade with one another to ensure the survival of both kingdoms. However, as I've explained in the past, the two kingdoms have a long history of tension between them -- which actually was the result of conflict over resources to begin with. However, despite this obvious codependency, neither one has been willing to suck up their pride and open direct negotiations between the two nations. (Fallon has tried several times during her rule, but has never once received a response from Pierre.)

So, this is where Oraine steps in. Oraine has a very hot environment, and aside from a few choice crops, not much of trade value grows there. (Their main exports, aside from a few "exotic delicacies", are fancy goods, such as fine clothes, art, and fancy furniture.) However, what Oraine does have is massive amounts of accessible coastline. Because of this, they have a long history of ship-building and maritime trade. Fortuitously for Oraine, Anvia and Oryn's border is mostly treacherous mountains, which makes overland travel difficult.

So, at some point in the past few centuries, some clever Orainian had an idea, and Orain graciously stepped in, offering to conduct trade between the two kingdoms -- for a fee, of course. Eager to continue their mutual cold-shoulder treatment, Anvia and Oryn were quick to accept the proposal. It was agreed upon that both Anvia and Oryn would be able to use Orainian ships to send their goods to each other, to Oraine, and beyond.

There are multiple companies (each owned by wealthy merchant families) that offer these services, both within the continent and beyond, and each is free to set their own price and negotiate their own service contracts with individuals, companies, or the nations themselves. However, they are charge a hefty tax that goes directly to the pockets of the ruler (currently Empress Adrienne) of Oraine.

Not only that, but Orainian merchants are well aware of how necessary their services are to both Anvia and Oryn. As such, their fees are often ridiculously overpriced. And Anvia and Oryn pay them, because they don't have any other choice.

(Well, they could choose to talk to each other and begin their own trading initiatives instead of settling for Oraine's horrid prices, but why would they ever do that?)

To tie all this back to the messy international politics of the continent, the Empress of Oraine has her own fleet of trading ships that carry out trades on her behalf. It is these ships that the rulers of Anvia and Oryn are required to use when they wish to send something more between them for political purposes. Orainian leaders have long claimed this is to "supervise" and "prevent increased hostility", but in reality it's just another way to line the ruler's pockets.

The rulers of both kingdoms have signed contracts with the Empire, including a rate of charge for the service. The Empress continually pushes to raise said rate, with the monarchs attempt to negotiate a lower price -- or at least keep the same one they had before. But it's a precarious slope, because if they push too hard, the Empress could retract her offer altogether, which would be disastrous (at least in the short term) for the two kingdoms, until they were able to communicate in a civil manner and establish their own trade barriers. (Of course, the Empress has no intention of actually rescinding her offer -- it's far too profitable -- but the monarchs don't know that...)

And that's all, folks!! To anyone who read all 1,092 words of this, I am hugging you (if you accept), and buying you your favorite meal. Hopefully this isn't too boring of a read...

#morrigan replies#worldbuilding#wip: atqh#atqh: worldbuilding#phew this is a doozy.#I'm SO SORRY Jacques... I know this is way more than what you asked for.#yk what? I'm gonna send this to my dnd group as proof they should let *me* negotiate our post-treason trade deal...#I think they'll think I'm crazy.#(dw they love me it's fine)#ooh also I gotta add a link to this post to my navigation page for ATQH!! I have my other two major worldbuilding dumps linked there.#the funnies thing about this is that I fucking HATE economics irl. Truly my least favorite subject. But then I go and write *this*...#make it make sense

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey local EU jurist to provide some more info on why farmers are mad at/about the EU, although not really but still a fair bit.

Main issues with the EU are inter-related, but if needs be, can be broken down like that

New norms in terms of health and safety, as well as more sustainable farming.

Problem is that while this is good on principle, it de facto makes their lives more difficult. Eg: ban of a particular pesticide at EU-level, ok, but they don't have an alternative to this pesticide.

2. Bureaucratie is a mess, but it is specifically bad to obtain CAP subsidies they are entitled to, it can mean being paid quite late.

They are already not super happy about having to depend on CAP-money, since ideally they would only rely on their own work and labour. But now, some payment have been delayed by MONTHS. (and you explained the issue of bureaucratie in general already, so not going back on that)

[This is one of the most problematic things politically as well, because CAP subsidies are a massive, MASSIVE part of the EU budget, but is not associated with particular support for the EU as a whole from its recipient. So more and more there is the impression in EU institutions that maybe there should be less money in the CAP after all]

3. Unfair competition from outside EU: trade deal are done at EU-level, and goods that are imported in the EU are not subject to the same heath and safety/sustainable norms.

That is the final nail in the coffin for many: the EU signs trade deals which make it easier for a non-EU country to export their farming output to EU states, but the norms they are subject to are not the same as the ones EU farmers are now subject to. So the impression is that EU is being quite hypocritical with its ~~sustainability~~ justification for health/safety/sustainability regulations when it comes to EU farmers, but is very chill with importing agricultural goods, often from overseas, that are not subject to these very regulations.

A proper breakdown of how much the really unacceptable situation many farmers are in is actually due to the EU is [looks up academic dictionnary] beyond the scope of this contribution but hopefully that at least explains why the EU specifically is currently the target of the French farmers!

thanks a lot for the additional info, really helps understanding the situation better !

i knew abt the annoyance towards Common Agricultural Policy but couldn't tell what was the main issue with it

(also love the break down in bullet points, très pédagogue !)

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Israeli Agriculture. Development of a Resource in Service of an Ideology

Israel’s agricultural system is characterized by an intensive system of production employing the latest engineering techniques and biotechnology. It contributed 3% to GDP and employed 2% of the population in 2006. Agricultural output in 2008 was worth about $5.5 billion, of which 20 percent was exported (Statistical Abstract of Israel, 2008). Israel’s agricultural system has evolved in large measure due to political and historical factors that extend back beyond the establishment of the state of Israel. In Israel, endogenous drivers of agricultural policy, including religion, culture, socioeconomics and demographics, take on monumental importance. Foremost among these is the role of Zionism in shaping agricultural and water policy. Agriculture was integral to the realization of the Zionist project since its inception. The settlers were led by a pioneering spirit and a back to the earth ethos, which aimed to wed the people to the land. This agrarian vision had two branches – conquering the land through its transformation and redemption, and simultaneously the creation of a new Jewish man. «In exile, the story goes, the Jewish people have been separated from nature, forbidden to work the soil and forced to be urban. The Jewish people will go back to the land, and they will be rebuilt by the land. In their return Jews will again tend to the earth and draw strength from their renewed biological rootedness» (Schoenfeld, 2004: 6)[.]

The central goal of Zionism was to create a geographical Jewish presence in Israel/Palestine. Collective agricultural settlement of the land was seen as an integral part of this process due to its role in population dispersal, securing peripheral areas and nurturing a bond between the Jews and their homeland. The other important goal for agriculture was self-sufficiency, in light of Israel’s inability to trade with her neighbours. For these reasons, Israeli is one example of a country pursuing agriculture despite its unprofitability, not to mention the unsuitability of the ecological environment to the agricultural activity (Da’na, 2000: 419)[.] This can be most clearly evidenced through Israel’s policy of water development. As Lipchin remarks (2003: 69): «In a country with naturally scarce water resources it is astonishing to see that Israel’s water policy does not reflect this natural scarcity». For example, for a long time much of Israel’s land mass was used to grow cotton, a water and pesticide hungry plant, rather than food (Richter & Safi, 1997: 211).

[...] Zionist ideology [...] interfaces with agricultural policy in numerous other ways, contributing to the unique character of the Israeli agricultural system. These include: the establishment of collective farms, including kibbutzim and moshavim, to defend against attackers in the early years; large capital inflows from the Jewish Diaspora, the United States and German reparations, permitting modern technologies; a preference for expensive Hebrew labour, including prohibitions against Arab labour; and large subsidies to the agricultural sector of inputs such as water, due to their strategic importance in laying claim to the land. Along with the agrarian vision, the Jews brought with them a European modernizing initiative, which saw the need to redeem the landscape and shape it to the settlers´ will. This implied a series of sweeping changes in agricultural production methods and land use patterns, which would transform the country.

– 2009. Leah Temper, “Creating Facts on the Ground: Agriculture in Israel and Palestine (1882-2000),” Historia Agraria 48, pp. 75-110.

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

argentina

Here is my story of Argentina. My credentials are that I have I spent the first three hours of my flight to Argentina reading its Wikipedia page plus followup google search results.

Argentina was rich. Then it became poor for no clear reason. It could become very rich again.

Let’s start with the last one.

Argentina is a major agricultural exporter that’s not even tapping its full biocapacity. Without making any prescriptive statements about whether they should, it’s descriptively true that they could be leaning on their natural resources much harder than they currently are.

The wind potential of the Patagonia region (southern third of Argentina) could in theory provide enough electricity to sustain a country five times more populous. But the infrastructure isn’t there to pipe it where it needs to go. Argentina is very urbanized, with 92% of its population in cities. (This is actually weird – if you look at countries ordered by urbanization, you get a bunch of tiny or fake countries like Bermuda or Macau, and then central category member countries like Uruguay, Israel, Argentina, and Japan.)

Argentina had a pretty good nuclear program. Decent record as a locus of scientific progress despite all the political problems and crumbling infrastructure. It’s got a high literacy rate.

It kind of reminds me of... (person who's only been to 7 cities voice) Berkeley?

Okay. Now let’s skip back to 1861. Argentina has won independence from the Spanish Empire. It’s about to get very Italian in here.

At time of independence, Argentina had the familiar-looking South American mix of white+native+black. But soon after independence the state started (0) genociding/expanding into the south (1) enacting liberal economic policies, and (2) encouraging European immigration. Italians liked this idea for some reason, so today, 60% of Argentinians are full or part Italian.

This wave of immigration changed Argentinian society enormously. In this period, Argentina became very wealthy and productive. In 1910 it was the seventh richest country in the world.

Twenty years later, dissatisfaction over the Great Depression fueled a coup and kicked off 50-70 years of political instability.

I like this graph. Look at the Y axis values – this is a log graph.

I have no clean explanation for what happened, but I can at least describe what happened after 1930.

In between coups, Argentina stays neutral in both world wars up until the US pressured it into declaring war on the Axis Powers in 1945. But then the Europe part of WWII ended a month later, so they probably didn't have to do too much. In 1946, Peron takes power.

(Sidenote: why did so many Nazis famously flee to Argentina? Argentina had lots of German immigrants & close ties to Germany. Peron, who'd found Hitler's ideology appealing since he was a military attaché in Italy during WWII, straight out ordered diplomats and intelligence officers to establish escape routes for Nazis, especially those with military/technical expertise.)

I still don’t know much about Peron. There's the socialist stuff: nationalized a lot of industries and improved working conditions. There's the dictator stuff: beating up and firing people to bring them into line, including university teachers (of course) and union leaders that Peron didn't like. He was really liked for a while, and then very disliked, and got exiled to Spain after a decade of rule.

Then there's a phase where no one manages to rule successfully, in part because getting approved by both Peronists and anti-Peronists is hard. This 1955-2003 phase reminds me a lot of Korean history around the same time – lots of military coups and assassinations and journalists getting tortured. Whenever I hit this phase in a country's Wikipedia page it just reads like TV static, interchangeable variable names swinging in and out of scope... even though there's got to be more than that.

When I first started reading about US Republicans and Democrats I got really confused because either they had 0 major differences or 70. Now that I've been in the States for a decade I have a sense for what major visions and underlying values differences they have, but it'd be hard to explain succinctly or in a way that other people will agree with. So something like that has to have been going on with various flavors of anti, sub, and classic Peronism that’s inscrutable to an outsider who’s spending 3 hours on learning about this.

At some point, comically, Peron comes back, wins an election with his wife as vie president, and dies of a heart attack. His wife takes power and does things like empowering the secret police to destroy her enemies, but girlbosses too close to the sun and is ousted after a year.

All this turmoil flattens out somewhat in 2003. I have no idea what went right. They tried Peronism! They tried anti-Peronism! They tried leftist terrorism and rightist terrorism! They tried OG Peron again! They tried Peron's third wife! They tried nationalization and privatization! They tried protectionism and not-protectionism!

Nestor Kirchner, whose rule coincided with the improvement, had "neo-Keynesian" policies, but who knows if that was it. He didn't run for reelection but said "try my wife, she'll do fine", and so she won the next cycle. Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner did well enough that she was reelected. People didn’t like her successor and brought her back as a vice president, but there were what sound like normal-for-South-America levels of corruption scandals during much of her time in office, and last month she was sentenced to six years in prison and a lifetime ban from holding public office.

I have a number of hypotheses as to why Argentina crashed so hard when it had and has so many prerequisites for success, and they all sound stupid when I write them out, so I won’t. But I will gesture at my confusion and amazement.

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

Intricate, invisible webs, just like this one, link some of the world’s largest food companies and most popular brands to jobs performed by U.S. prisoners nationwide, according to a sweeping two-year AP investigation into prison labor that tied hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of agricultural products to goods sold on the open market.

They are among America’s most vulnerable laborers. If they refuse to work, some can jeopardize their chances of parole or face punishment like being sent to solitary confinement. They also are often excluded from protections guaranteed to almost all other full-time workers, even when they are seriously injured or killed on the job.

The goods these prisoners produce wind up in the supply chains of a dizzying array of products found in most American kitchens, from Frosted Flakes cereal and Ball Park hot dogs to Gold Medal flour, Coca-Cola and Riceland rice. They are on the shelves of virtually every supermarket in the country, including Kroger, Target, Aldi and Whole Foods. And some goods are exported, including to countries that have had products blocked from entering the U.S. for using forced or prison labor.

Many of the companies buying directly from prisons are violating their own policies against the use of such labor. But it’s completely legal, dating back largely to the need for labor to help rebuild the South’s shattered economy after the Civil War. Enshrined in the Constitution by the 13th Amendment, slavery and involuntary servitude are banned – except as punishment for a crime.

That clause is currently being challenged on the federal level, and efforts to remove similar language from state constitutions are expected to reach the ballot in about a dozen states this year.

Some prisoners work on the same plantation soil where slaves harvested cotton, tobacco and sugarcane more than 150 years ago, with some present-day images looking eerily similar to the past. In Louisiana, which has one of the country’s highest incarceration rates, men working on the “farm line” still stoop over crops stretching far into the distance. {read}

#article#prison#labor#workers#this is capitalism#capitalism is a scam#capitalism is violence#AP#associated press#slavery#13th amendment

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brazil, an agricultural superpower and the world’s largest net exporter of food, has also seen hunger and poverty rise in recent years, after the administration of Jair Bolsonaro dismantled social policies, amid an economic downturn. Heartbreakingly, almost three in every five households do not always have enough to eat, while 33 million people (about 15 percent of the population) are going hungry.

But now President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who was inaugurated in January, has stepped up. “I am obsessed with fighting hunger … I want workers to once again be able to have three meals a day in a dignified manner and to provide quality food for their children,” he said as he launched the Brasil Sem Fome (Brazil Without Hunger) plan in late August.

Arguably the most comprehensive set of anti-hunger policies the world has ever seen, this bold plan opens a new front in the global war on hunger, just as hope was beginning to fade.

The Brasil Sem Fome – on which the National Food and Nutrition Security Council (CONSEA), the organisation I chair, advised – has far-reaching but simple goals. It aims to wipe Brazil off the UN Hunger Map by 2030 – no ifs or buts – and to ensure that more than 95 percent of households are food secure by the end of the decade. It also aims to improve access to healthy diets and kick-start a transition to sustainable agriculture.

Some 32 programmes and policies will be leveraged to achieve these goals – from cash transfers to poor households to the purchase of healthy school food from smallholder farmers; from agroecological transition payments to support for Black and rural women, to bolstering protection of the Amazon. All of this will come under an apparatus that is purpose-built to bring the voices of food-insecure and marginalised people into the decision-making process.

If this plan sounds familiar, that is because it is a recast of the Fome Zero (Zero Hunger) policies introduced by Lula’s first administration in 2003 – but with an extra dose of ambition on democratic governance and sustainably produced food, reaching the most marginalised groups.

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The Gaza Strip is in a humanitarian disaster, a man-made crisis resulting from Israeli policy. The lives of nearly two million people are at stake.” - Btselem report 2017

In 2015, the UN warned that without changes, Gaza would become “unlivable” by 2020. Since then, Israel has tightened its policies, and Gaza has been already unliveable for the following points:

The blockade of Gaza, separating it from the West Bank, has been ongoing since the 1990s. It restricts travel, imports, exports, and more, pushing Gaza into an economic recession and dependency on aid.

Gaza's economy has collapsed, with high unemployment and food insecurity. Infrastructure and public services were already deteriorating, with contaminated water, power cuts, and healthcare shortages.

Till Aug 2023, the Israeli occupation continued to raze farm land, demolish residential structures and industrial facilities, and seize buildings inside the strip.

Also, deliberate herbicide spraying and land destruction have further harmed Gaza's agricultural sector.

The healthcare crisis in Gaza was a severe and ongoing humanitarian issue.

The Israeli blockade, three devastating wars, has meant that the availability of medical services is seriously inadequate to meet the health needs of the two million Gazans.

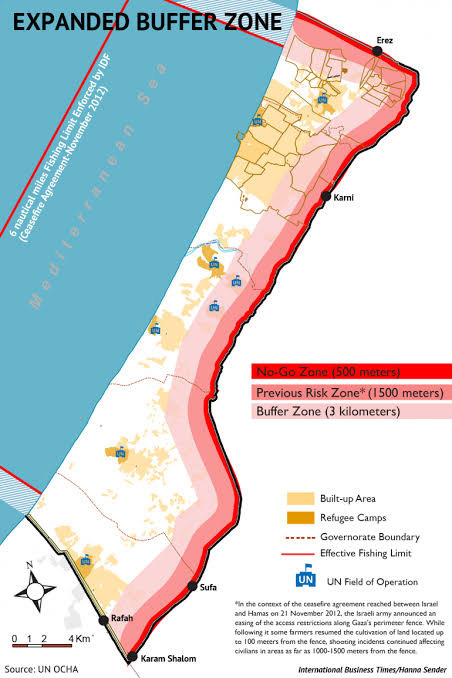

Gaza's "no-go" zones near the border create a buffer zone and have always been a continuous threat to the lives of those who live and work there.

Israel's control over Gaza extends to its airspace and territorial waters, which it has maintained since occupying Gaza in 1967. This control has significant implications for Gaza's residents.

Israel's control of Gaza's airspace enables it to monitor activities on the ground, interfere with radio and TV broadcasts, and launch airstrikes at will.

The Oslo Agreements allowed Palestinians to build an airport, and accordingly, Gaza Airport opened in 1998, but then it was closed by Israel in 2000 and has remained closed since then.

In 2001, the Israeli Air Force bombed the airport's runways, and it was later used as an Israeli military base. Israel committed to discussing reopening the airport, but no progress has been made on this front.

Israel's control of Gaza's territorial waters is another aspect of the crisis. While there's no physical barrier along Gaza's coast, residents need Israeli permits to access the sea, with restrictions on how far they can go from shores.

In the Interim Agreement, Israel agreed to allow fishing boats from Gaza up to twenty miles from the coast, but in practice, the limit has often been set at twelve miles and then it was reduced later to only 3 miles!

The promise of a seaport in Gaza has remained unfulfilled. Despite initial infrastructure work, the project was halted, and Israel agreed in 2005 to cooperate in its establishment. But surprisingly, no progress has been made !

The situation in Gaza is dire, while Israel formally withdrew its settlers and military from the Gaza Strip in 2005,in

In practice, Gaza remains under Israeli occupation.

Hamas wasn't the only resistance group that defended Palestinian rights against the occupiers. The resistance started since the very beginning when Israel was declared as a state in 1948.

The "Fedaeyon" had started it all as a resistance,and Hamas still continues their legacy.

Resistance by all means,violent and nonviolent, is essential,and spreading awareness is a must to stop the atrocities committed against the Palestinians for years.

Colonization is a crime against humanity, and colonized people have the right to resist by any means necessary.

Vietnam's 9-year fight for freedom against France shows that resistance is never futile,even when faced with a much more powerful enemy. Calling similar movements "terrorism"is a conspiracy to silence legitimate dissent and perpetuate oppression.

And if people were submissive to colonization they will face the same destiny as the Native Americans, who were colonized and forced onto reservations, where their culture was suppressed and their children were forbidden to speak their own language.

So ask yourself: If you were Palestinian, would you see Hamas as a "terrorist" group or a "resistance" movement defending your right to live while the world has already turned a blind eye?

The disheartening reality that the security council fails to agree on a ceasefire appears much like what Franklin once said as "Demkcracy is like two wolves and a lamb voting on what's for lunch," revealing the fragility of humanity & democracy as the moral compass quivers.

Israel has been playing the US and the Western media and public like a fiddle for decades. They've mastered the language that resonates with Americans.

All that Israel wants is for the US to destroy another Arab nation on Israel's behalf & cause more destabilization.

#gaza#free gaza#gaza strip#gazagenocide#gaza news#gazaunderfire#gazaunderattack#save gaza#stand with gaza#palestine#from the river to the sea palestine will be free#patients and doctors#palestinian genocide#justice for palestine#pray for palestine#israel palestine conflict#save palestine#long live palestine#palestine news#palestinian film#palestinian#palestinians#genocide#gaza under attack#let gaza live#help gaza#northern gaza#gaza genocide#news on gaza#war on gaza

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Traditionally incoming Argentinian presidents give an inauguration speech inside of Congress to other politicians. Javier Milei, a former “tantric sex instructor” turned libertarian economist, symbolically gave his speech with his back to the Congress facing towards the people.

“For more than 100 years, politicians have insisted on defending a model that only produces poverty, stagnation, and misery,” President Milei said. “A model that assumes that citizens exist to serve politics, not that politics exists to serve citizens.” He also promised an “end a long and sad history of decadence and decline” and promote a new era based on peace, prosperity, and freedom.

Since his headline-making election victory last month, media portrayal of Milei has ranged from dismissive to condescending, often depicting him as an eccentric “far-right populist.” Yet, since taking office, Milei has shelved many of his campaign’s more contentious proposals and begun implementing a radical but, by international standards, orthodox reform plan to revitalize Argentina’s faltering economy.

Milei inherited a challenging situation. Argentina’s economy has shrunk by 12 per cent over the last decade, annual inflation reached an extraordinary 160 per cent in November, while the poverty rate increased to 40 per cent in the first half of 2023.

Argentina has a fascinating economic history that led up to this point. In the 19th century post-independence Argentina adopted a liberal constitution that helped deliver an impressive economic expansion.

By the early 20th century, Argentina was one of the world’s richest countries, driven by agricultural exports. Real wages were comparable to Britain and only slightly below the United States. Millions fled destitution in southern Europe for a new life in Argentina. Buenos Aires has been labelled the “Paris of South America” because of spectacular neoclassical architecture built during this era.

This turned to disaster over the subsequent decades because of collectivist rule – from military dictatorships to avidly socialist leaders. Argentina nationalised industries, subsidised domestic production, limited external trade, and introduced an unaffordable welfare state. This has become known as the Peronism, named after 20th century president Juan Domingo Perón, a leftist populist leader who supressed opposition and controlled the press.

This agenda accelerated in recent decades under self-identifying Peronist leaders, turning Argentina into one of the world’s most closed and heavily regulated countries. The latest Human Freedom Index places Argentina at 163rd in the world for openness to trade and 143rd for regulatory burden. This has culminated in an economy on the precipice of economic disaster.

Not wasting any time, Milei has proposed a mega package of over 350 economic reforms to open the economy and remove regulatory barriers. This includes privatising inefficient state assets, eliminating rent controls and restrictive retail regulations, liberalising labour laws, lifting export prohibitions, and allowing contracts in foreign currencies.

There has been a notable absence of some of most radical ideas – such as legalising organ sales or banning abortion. He has also put on hold plans to dollarise the economy and abolish the central bank. Instead, at least by international standards, the agenda contains several orthodox economic reforms.

Many of the measures – such as cutting spending to get the deficit (currently at 15 per cent of GDP) under control, opening the country up to international trade, and liberalising the airline industry through ‘open skies’ policy – would be required to join the European Union. The government is eliminating capital and currency controls and allowing the peso to devalue – measures that the IMF’s managing director Kristina Georgieva said these are important to stabilise the economy.

There are undoubtedly significant challenges ahead and some darker elements to agenda.

Milei has been, uncharacteristically for a politician, honest that “in the short term the situation will get worse”. The removal of price controls, for example, will increase inflation until demand and supply can stabilise to end shortages. But, he says, “then we will see the fruits of our efforts, having created the foundations of a solid and sustainable growth over time.”

The government is facing significant opposition, with the union movement organising mass protests and threatening a general strike. The government has responded by proposing questionable new anti-protest laws, that include lengthy jail sentences for road-blocking and requirements to seek permission for gatherings of more than three people in a public place. Milei, who could struggle to get much of his agenda through Argentina’s Congress, is asking for sweeping emergency presidential powers until the end of 2025. This raises serious questions about democratic accountability.

Nevertheless, there are some positive early signs. Since Milei’s election Argentina’s flagship stock index has risen by almost one-third and the peso’s value has not collapsed. Argentina could soon benefit from a major new shale pipeline pumping one million barrels of crude a day (helped along by reforms that allow exports of oil and sales at market prices) and the mining of the second largest proven lithium reserves in the world.

Argentina has long served as a solemn reminder that prosperity is neither inevitable nor unassailable. Misguided policies can transform mere challenges into a profound crisis. Milei is offering a glimmer of hope: redemption may just be possible. Let’s also hope that Britain’s leaders can similarly take the path of reform, ideally before things get as bad as Argentina.

Matthew Lesh is the Director of Public Policy and Communications at the Institute of Economic Affairs

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Unsettled Plain defies the conventional framings of the region’s [”Middle East”] history. The protagonists of this book are the people often left out or relegated to a minor role: pastoralists, peasants, workers, and migrants who lived in Ottoman countryside. Many books adopt national or imperial geographies, but I have used a space that destabilizes such geographies. Call it Cilicia, Çukurova, or the Adana region -- the book is about a coherent, interconnected place that is hidden on the map today.

---

During the nineteenth century, this corner of the Mediterranean at the border of Syria and Turkey contained diversity that would surprise Anglophone readers accustomed to images of the Middle East painted with a broad brush. [...] Speakers of Turkish, Arabic, Armenian, Kurdish, and Greek lived side by side there for centuries, not just in cosmopolitan cities but also in the vast hinterland. With large-scale migration during the latter half of the nineteenth century, Tatar, Circassian, and Chechen refugees from the Russian Empire, as well as Cretan Muslims and various people from the Balkans built new settlements in the region [...]. An extraordinary array of communities that made up the population of the late Ottoman Empire shared this one small place.

Among rural inhabitants, there were many ways of life, ranging from long-distance, nomadic patterns of grazing sheep and goats to intensive, plantation-style cultivation of cotton for global export. And in a space only a little bigger than modern-day Lebanon, there was also intense environmental contrast. Foreigners used to remark that one could set out on foot from a lowland city like Adana, which might have felt just as hot as Egypt on a summer day, and in two or three days be in mountain spaces reminiscent of the Swiss Alps. That is in fact precisely how the local people lived, migrating between the highland and lowland micro-climates on a seasonal basis and spending the summer in those precious mountain spaces. So in all these ways, the world of The Unsettled Plain is more complex than what we get in Ottoman histories written from the vantage point of Istanbul or Cairo, or for that matter the histories of the modern Middle East written inside of nation-state containers. [...]

---

The central issue that runs throughout the book is malaria [...]. Malaria is associated with the tropics today, but it used to be very widespread not only in the former Ottoman Empire but also Europe and North America. I use malaria to show how the transformation of the Ottoman Empire from the Tanzimat reforms of the mid-nineteenth century onward impacted rural people. Settlement policies and the commercialization of agriculture disrupted malaria avoidance strategies that were rooted in an intimate understanding of the local environment, resulting in catastrophic malaria epidemics for resettled or displaced people and the gradual intertwining of malaria with agricultural labor and increasingly uneven relations between landowners and workers. Far from being unique to the Ottoman experience, this story harkens to the experiences of many spaces throughout nineteenth-century empires.

---

Each chapter of the book circles back to the question of malaria through different interlocking themes, and those themes are [...] ecology, the state, capitalism, war, and science. Chapter 1 is focused on aspects of Cilicia’s local ecology and politics before the Tanzimat period, and Chapter 2 studies the impacts of state reform and settlement policy during the high Tanzimat period of the mid-nineteenth century. Chapter 3 studies how a new form of capitalism centered on cotton export shaped this region during the last decades of the Ottoman period, and Chapter 4 studies how much of that new world was destroyed during the World War I period and the subsequent Franco-Turkish war. Chapter 5 traces continuities between the late Ottoman period and early Republican period in Turkey, focusing on the themes of science and technology and examining the role of medicine and public health in the remaking of the countryside. [...]

---

Between modern-day residents of Çukurova, those who have settled in Istanbul, Ankara, or other cities in Turkey, and those who have emigrated abroad to Germany or elsewhere, a sizeable percentage of people from modern Turkey either claim this region as home or have some personal connection to it. There is also a substantial portion of the Armenian diaspora in the United States, France, Lebanon, Armenia, and elsewhere who think of Cilicia as their ancestral homeland.

---

Words of Chris Gratien. As interviewed by Jadaliyya. Regarding Gratien’s book The Unsettled Plain: An Environmental History of the Late Ottoman Frontier (2022). This text and the interview were published at Jadaliyya online on 25 April 2022. [Bolded emphasis added by me.]

110 notes

·

View notes